Abstract

Health service planners, administrators and providers need to understand the patients’ perspective of health services related to osteoporosis to optimise health outcomes. The aims of this study were to systematically identify and review the literature regarding patients’ perceived health service needs relating to osteoporosis and osteopenia. A systematic scoping review was performed of publications in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO (1990–2016). Descriptive data regarding study design and methodology were extracted and risk of bias assessed. Aggregates of patients’ perceived needs of osteoporosis health services were categorised. Thirty-three studies (19 quantitative and 14 qualitative) from 1027 were relevant. The following areas of perceived need emerged: (1) patients sought healthcare from doctors to obtain information and initiate management. They were dissatisfied with poor communication, lack of time and poor continuity of care. (2) Patients perceived a role for osteoporosis pharmacotherapy but were concerned about medication administration and adverse effects. (3) Patients believed that exercise and vitamin supplementation were important, but there is a lack of data examining the needs for other non-pharmacological measures such as smoking cessation and alcohol. (4) Patients wanted diagnostic evaluation and ongoing surveillance of their bone health. This review identified patients’ needs for better communication with their healthcare providers. It also showed that a number of important cornerstones of therapy for osteoporosis, such as pharmacotherapy and exercise, are identified as important by patients, as well as ongoing surveillance of bone health. Understanding patients’ perceived needs and aligning them with responsive and evidence-informed service models are likely to optimise patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is increasingly being recognised as an important public health concern due to an ageing population and rise in chronic diseases [1]. It is estimated that one in two women and one in five men over the age of 50 will sustain a fracture due to osteoporosis [2]. Fragility fractures related to osteoporosis are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The direct medical costs of this global health burden are substantial, amounting to an estimated $17 billion in the USA in 2005 [3], € 37 billion in the European Union in 2010 [4] and more than $9 billion in China in 2010 [5]. This is projected to surpass $25 billion by 2025 [3, 5, 6].

To close the evidence-practice gap in osteoporosis management and address the burden of osteoporosis [6, 7], several peak organisations have developed clinical practice guidelines to guide clinicians in optimising bone health and managing osteoporosis [8,9,10,11,12]. Recent strategies have been implemented to improve the uptake of evidence-based recommendations, such as education programs, fracture-liaison services, orthogeriatic models of care and audits of healthcare services [13,14,15]. However, despite these measures, the management of osteoporosis and bone health following fragility fractures remains inadequate [16,17,18]. Previous studies have shown that just up to 25% of patients identified as high risk had further investigations for osteoporosis and less than 20% of patients with osteoporosis or a history of fragility fractures received treatment to prevent future fractures [15,16,17, 19, 20].

Optimal osteoporosis outcomes, for the patient and health service, depend on a variety of factors at multiple levels—from health policy through to patients’ self-management behaviours: all of these factors may affect the effective implementation of guidelines and models of care [21]. Understanding why management deviates from guidelines so frequently is important to improve bone health outcomes. A recent seminal report by the International Osteoporosis Foundation [6] has summarised current international gaps in quality service delivery for people with poor bone health and has suggested strategies from a health services and policy perspective for improvement. However, these issues are not considered through the lens of the consumer. As management requires the patient to access and use healthcare services, identifying their perceived needs may provide insight into why optimal management does not occur, or is not sustained (of particular relevance to osteoporosis management). It may also suggest more effective strategies for healthcare providers and policy makers for implementing consumer-centred strategies and promoting patient-centred care: taking the patients’ perceived needs into account may inform clinical decision making, helping doctors to optimise osteoporosis treatment. Although there are published systematic reviews that examine patients’ health beliefs relating to osteoporosis [22] or their experience of living with osteoporosis [23], these do not examine the patients’ perceived needs of health services. There have also been several studies that explore the patients’ perspective and perceived needs of health services for osteoporosis, either directly or indirectly, but no review has been performed to identify and summarise the existing literature. Therefore, we performed a systematic scoping review to identify the literature regarding patients’ perceived needs for health services for osteoporosis and osteopenia management.

Methods

A systematic scoping review was performed to identify what is known about patients’ perceived health service needs for osteoporosis and osteopenia within a larger project examining the patients’ perceived needs relating to musculoskeletal health [24]. Throughout, we refer to ‘osteoporosis’, which is inclusive of osteopenia. Given the breadth of the topic, a systematic scoping review, based on the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [25], was conducted to comprehensively explore of the patients’ perspective, map the existing literature and to identify gaps in the evidence [26, 27].

Search strategy and study selection

An electronic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO was performed to identify studies examining patients’ perceived needs relating to osteoporosis health services between January 1990 and July 2016. This time period was chosen to include relevant studies examining the current patient perspective. The search strategy was developed iteratively by an academic librarian, clinical researchers (rheumatologists and physiotherapists) and a healthcare organisation representing consumers with osteoporosis and musculoskeletal disorders. It combined both text words and MeSH terms to capture information regarding the constructs of osteoporosis and bone health, patients’ perceived need(s) and factors related to health services. The term ‘patients’ perceived needs’ was used to broadly capture the patients’ perception of their capacity to benefit from services, including their expectations of satisfaction with and preferences for various services [28]. The term ‘health services’ includes ‘services relating to the diagnosis and treatment of disease, or the promotion, maintenance and restoration of health’, as described by the World Health Organisation [29]. The term ‘health service needs’ describes the patients’ perception of their capacity to benefit from services relating to the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, or the promotion, maintenance and restoration of health, relating to osteoporosis. The detailed search strategy for MEDLINE is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Two investigators (LC and PS) independently assessed all the titles and abstracts of the studies identified by the initial search for relevance. The initial screening of manuscripts identified by the search strategy was designed to be as inclusive as possible to identify relevant studies, within the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to capture the breadth of the literature. The reference lists of retrieved articles and review articles were also manually assessed for further studies for inclusion. To be included in the review, studies had to (1) concern patients older than 18 years and at risk of osteoporosis or having osteoporosis (either diagnosed by a physician, based on bone densitometry results, or individuals taking medications for osteoporosis); (2) report on patients’ perceived needs of health services; (3) concern osteoporosis (either primary or secondary), osteopenia or bone health; and (4) full-text articles. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included to provide an in-depth review of the topic. Only studies in the English language were retained due to resource constraints. Studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria and relevant reviews were retrieved, and the full text was assessed for relevance by two investigators (LC and PS). Any disagreements in the inclusion of studies were resolved through consensus or reviewed by a third investigator (AW).

Data extraction and analysis

Two investigators (LC and PS) independently extracted the data from relevant studies using a standardised data extraction form developed for this scoping review. The included studies were described and reported according to the following: (1) author and year of publication; (2) study population (patient age and gender, population source, population size and definition of osteoporosis); (3) primary study aim; and (4) description of the study methods. Two authors (LC and PS) independently reviewed and extracted relevant data from the included studies using the principles of meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative data [30]. This involved a process of identifying key concepts from the included studies, and reciprocal translational analysis was undertaken to translate and compare the concepts from individual studies to other studies and gradually explore and develop overarching themes [31]. Importantly, reciprocal translational analysis allows for the development of a concept or theme by considering different viewpoints related to the same issue, described in different ways. In the first stage, one author (PS) initially developed a framework of concepts and underlying themes, based on primary data in the studies and any pertinent points raised by the authors in the discussion. In the second stage, another author (LC) independently reviewed the studies and further developed the framework of themes and concepts. In the third stage, two senior authors (FC and AW) with over 10 years of clinical rheumatology consultant-level experience independently reviewed the framework of concepts and themes to ensure clinical meaningfulness and face validity.

Methodological quality assessment

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, two reviewers independently assessed all of the included studies (LC and PS). For qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used [32]. The risk of bias tool was utilised to assess the external and internal validity of quantitative studies: low risk of bias of quantitative studies was defined as scoring 8 or more ‘yes’ answers, moderate risk of bias was defined as 6 to 7 ‘yes’ answers and high risk of bias was defined as 5 or fewer ‘yes’ answers [33]. The reviewers discussed and resolved disagreements through consensus. Any disagreements in scoring were reviewed by a third reviewer (AW).

Results

Overview of studies

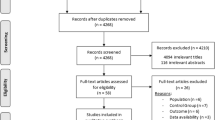

The search strategy identified 1030 studies, of which 33 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. A PRISMA flowchart detailing the study selection is shown in Fig. 1. The descriptive characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Of the included studies, 20 were from North America [34, 35, 37,38,39,40, 43, 45,46,47,48, 52, 54,55,56,57, 59, 60, 64, 65], 6 from Europe [41, 42, 50, 53, 61, 67], 3 from the United Kingdom [36, 49, 51], 1 from South America [66] and 1 from the Middle-east [63]. There was one multi-centre study [44]. A total of 16,975 patients were included; the sample size of the quantitative studies ranged from 21 to 3438, with a median of 765 and the sample size of the qualitative studies ranged from 14 to 164, with a median of 25. Across the studies, 95% of the participants were female: 22 studies examined only female participants [34, 36, 38, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52, 53, 58, 60, 61, 63,64,65,66,67] and the remaining 11 studies evaluated mainly women [35, 37, 39, 42, 43, 51, 54,55,56,57, 59]. The mean age of participants was 68 years. Eight studies recruited participants with a previous fragility fracture or at high risk of osteoporotic fractures and 6 studies included patients requiring prescription medications, with or without a previous history of fractures. Only 4 studies provided details regarding other co-morbidities: two studies reported that more than 50% of their participants had less than one co-morbidity [51, 61] and two studies had more than 70% of participants with more than two co-morbidities [42, 63].

Nineteen studies used quantitative methods [34, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 46, 47, 50,51,52, 58, 59, 61, 63,64,65,66,67], all of which were cross-sectional surveys; of these, 13 used questionnaires [37, 39, 42, 46, 47, 50, 51, 58, 61, 63, 65, 67], 5 used surveys [34, 40, 44, 59, 64] and 1 used interviews [52]. Fourteen used qualitative methods [35, 36, 38, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 53,54,55,56,57, 60]; of these, 10 used interviews [35, 36, 38, 41, 48, 49, 54,55,56,57], 4 used focus groups [38, 43, 45, 53] and 1 used video recordings [60]. There were no mixed method studies.

The inclusion criteria for study participants varied across studies. Patients were classified as having osteoporosis based on bone densitometry in seven studies [34, 41, 46, 48, 53, 65], requiring prescription medications in six studies [42, 45, 52, 59, 63, 66] or on the basis of previous fragility fractures or high risk of osteoporotic fractures in eight studies [37,38,39, 47, 54,55,56, 61]. The diagnosis of osteoporosis or osteopenia was unspecified in 13 studies [36, 40, 43, 44, 49,50,51, 57, 58, 60, 64, 67].

Quality of studies

Quality assessments of the included studies are presented in the Supplementary Appendix, Figs. 1 and 2. The quality of qualitative studies was poor, especially for CASP criteria 4 to 6 (Supplementary Appendix, Fig. 1). The quantitative studies were of low quality: 18 studies were at high risk of bias and 1 study was at moderate risk of bias (Supplementary appendix, Fig. 2). These scores for both qualitative and quantitative studies reflected potential biases with participant recruitment and data collection.

Results of review

Four main areas of patients’ perceived needs of health services for osteoporosis emerged from this review.

Patients’ perceived needs of healthcare providers in the management of their bone health and osteoporosis (Table 2)

Patient preference for consulting medical practitioners and their role

Eight studies identified patients’ preference for seeing a medical practitioner for osteoporosis and their perceived role [35, 38, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 56]. Four studies found that patients sought care from a medical practitioner for their bone health [43, 45, 48, 49]. Two studies reported that patients believed and trusted medical specialists such as endocrinologists and rheumatologists more than their primary care physician, and they perceived their specialists as being more interested in their bone health than primary care providers [35, 43]. Feldstein found that patients who had sustained a fracture advocated for standardised protocols for integrating and involving medical specialists in the management of osteoporosis [38]. The role of the medical practitioner was perceived to perform a thorough examination [41], provide osteoporosis information and education [38, 41, 49, 56], initiate screening for osteoporosis [38, 56], prescribe and monitor treatment [38, 45, 48, 56] and provide support for optimal self-management [45].

Desirable characteristics of the medical practitioner

Four studies reported on the desired characteristics of medical practitioners in the management of osteoporosis [36, 41, 45, 52]. Besser found that patients wanted to be involved with decisions related to osteoporosis treatment [36]. Lau and Rizzoli reported that the patients wanted follow up from healthcare providers for support and monitoring of medications [45, 52]. Also, patients wanted their osteoporosis to be taken seriously by their practitioners [41] and to be able to discuss medication problems and concerns [45]. Lau reported that patients wanted non-judgemental care [45].

Dissatisfaction with, or concerns about, medical and non-medical practitioners

Six studies identified patients’ dissatisfaction and concerns with medical practitioners relating to their osteoporosis management [35, 36, 43, 46, 48, 49]. Patients perceived poor communication, lack of an adequate explanation of the diagnosis and poor continuity of care to be barriers to a good relationship with their doctor [36, 46]. Patients were dissatisfied with the lack of time during consultations and felt that they were unable to ask questions or raise issues with medications with their physicians [35, 36, 43]. Furthermore, they felt that their primary care providers were dismissive of their concerns about osteoporosis [35]. Patients were disappointed with the strong focus on medications and expressed distrust when medical practitioners were too quick to recommend medications, rather than adopt a more holistic approach to care, inclusive of non-pharmacologic options [48, 49]. Moreover, patients reported inconsistent recommendations from different practitioners, and in particular, they found the advice from other disciplines of healthcare, such as nutritionists, physiotherapists and chiropractors to be contradictory, sporadic and not forthcoming [35].

Patients’ needs related to pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis and bone health (Table 3)

Perceptions and roles of medications

Eleven studies examined the patients’ preference for medications and the perceived role of pharmacotherapy [36, 37, 39, 45, 47, 48, 54, 56, 59, 61, 65]. While some studies found that patients had a preference for pharmacological management of osteoporosis [36, 37, 39, 45, 54, 56, 59], other studies did not [45, 48, 54, 56]. The patients who were more willing to take medication had been told of the diagnosis of osteoporosis [47, 65] and had previous bone mineral density (BMD) testing [47], believed they were susceptible to fractures [59], had a good relationship with their doctor or trusted their physicians [54, 59] and believed in the effectiveness of medications [65]. The role of pharmacotherapy was perceived to help eliminate symptoms, help avoid further deterioration in bone health, provide extra strength for the bone and improve bone density [48, 54]. A single study that compared patients’ predilection for pharmacotherapy compared to hip protectors in high-risk patients found that although patients preferred bisphosphonates for the management of their osteoporosis, older patients were more likely to avoid prescription medications and preferred hip protectors [39]. In contrast, several studies reported that patients did not prefer pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis management [45, 48, 54, 56]. Mauck reported that most women who were admitted to a tertiary hospital after a fragility fracture were either unaware of osteoporosis or had never considered pharmacological treatment [47]. Some patients viewed osteoporosis as a consequence of ageing and did not perceive a need for medications [48] and some patients wanted a drug holiday from bisphosphonate treatment [56]. Also, some patients preferred lifestyle modifications rather than pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis management [45, 48, 56].

Concerns about medications

There were 12 studies that reported the patients’ concerns with osteoporosis medications [34, 36, 41,42,43, 45, 48, 53, 54, 60, 65, 66]. Patients who believed they had good health were concerned about taking medications for a condition that was otherwise asymptomatic [53, 60]. Those with a family member who had osteoporosis with no complications were less likely to perceive a benefit with pharmacotherapy [53, 60]. Moreover, patients were unwilling to take medications if they had family members or friends who had experienced adverse events, or if they heard about side effects from the media [34, 45, 48]. Potential side effects from medications were a major concern for many patients [34, 36, 41,42,43, 45, 48, 53, 54, 60, 65, 66], as well as possible drug interactions from polypharmacy [36, 66], the potential for addiction and overdosing [36]. In particular, some patients had specific concerns including the potential for jaw osteonecrosis, gastrointestinal side effects, breast and oesophageal cancer, thrombotic effects and cardiovascular events [34, 42, 45, 53, 66]. Patients also reported a dislike of chemicals [36, 45], distrust of medications [65] and of pharmaceutical companies [36]. Dissatisfaction with their doctor or the physician’s attitude were other reasons for patients to not want to pursue pharmacotherapy for the management of osteoporosis [54, 66]. Furthermore, Iversen reported that patients found the method of medication administration and instructions difficult to understand and remember [43].

Preferable therapeutic attributes of medications

Patients’ preferred therapeutic attributes of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy were also examined through this review [40, 42, 44, 45, 50,51,52, 58, 63, 64, 67]. Patients wanted osteoporosis medications to be effective [40, 44, 64], to not interact with other medications [52], have fewer side effects [52] and be easier to administer [44, 52, 64]. A single study evaluating combination packaging of bisphosphonates and calcium supplementation found that patients preferred the ease and convenience of combination packaging [67]. Some studies found that patients preferred weekly to daily or monthly dosing [40, 44, 58, 64]; however, other studies reported a preference for monthly administration [42, 66].

Patients’ perceived needs of non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis (Table 4)

Four studies examined the patients’ perceived needs of non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis [37, 38, 45, 57]. Patients’ preference for calcium and vitamin D supplementation were examined by four articles [37, 38, 45, 57], which found that patients wanted these supplements for osteoporosis management. Patients expressed more willingness and comfort with taking supplements than prescription medication [38] and believed them to be more natural and safe [45]. Bogoch and Sale found that patients see a role for exercise for osteoporosis management [37, 57]. There were no studies identified that examined the patients’ perceived needs of other non-pharmacological strategies such as smoking cessation, attitudes to interventions related to falls prevention and avoidance of excessive alcohol.

Patients’ perceived needs of investigations for osteoporosis (Table 5)

Three studies described patients’ perceived need for investigations for the diagnosis of osteoporosis [48, 53, 56]. Patients saw a role for bone densitometry testing for diagnostic evaluation [48, 56]. Rothmann found that patients interpreted screening for osteoporosis as an opportunity to get reassurance about bone health and to optimise their own general health [53]. Three studies described patients’ perceived need for investigations for ongoing surveillance of bone health [36, 48, 56]. Patients wanted feedback from bone density scans to evaluate the efficacy of pharmacotherapy [36, 48]. Sale reported that patients felt that had to ‘nag’ their physicians and follow up their own results [56].

Discussion

This systematic scoping review identified 33 studies that explored patients’ perceived health service needs for osteoporosis. We identified specific health service needs among people with osteoporosis or osteopenia, highlighting opportunities for specific enhancement in models of service delivery for these conditions to ensure they continue to evolve in a patient-centred manner.

This review found that patients sought care from medical practitioners for the management of their osteoporosis [35, 43, 45, 48, 49]. In particular, patients tended to prefer management from specialists over primary care physicians. This is similar to other musculoskeletal conditions, such as low back pain [68, 69], and may reflect a lack of confidence or prioritisation by general practitioners in the management of bone health [70]. This may be attributed to limited knowledge of primary care providers [70] and suggests a need for future targeted education programs to bridge this gap, which have been shown to improve patient outcomes in osteoporosis as well as other chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma and congestive cardiac failure [71, 72]. Patients’ expectation of healthcare providers was to perform a thorough examination, provide osteoporosis information and education, initiate screening for osteoporosis and to prescribe and monitor treatment [38, 41, 45, 48, 49, 56]. They wanted supportive and non-judgemental physicians [35, 45, 52], which enabled and promoted shared decision making. Indeed, this represents a key enabler to more effective self-management and sustainability to positive bone health behaviour change. They expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of time given by physicians, poor communication [35, 36, 43] and the inconsistent messages from different healthcare providers [35], again highlighting the need for standardisation in cross-discipline education. Additionally, the dismissive approach, strong focus on pharmacotherapy and lack of continuity of care from healthcare providers were other areas of discontent among patients [35, 36, 43, 46, 48, 49]. It also underscores the patients’ preference for patient-centred care and reinforces the need for clinicians to provide holistic care to improve the provider-patient relationship, which may facilitate improved uptake of osteoporosis clinical guidelines. This desire for improved communication from healthcare providers and holistic care is a common perceived need of patients with other chronic musculoskeletal conditions, including osteoarthritis, low back pain and inflammatory arthritidies [24, 73].

Patients perceived a role for medications in the management of osteoporosis [36, 37, 39, 45, 54, 56, 59]. This is congruent with current clinical practice guidelines for osteoporosis which emphasise the use of pharmacotherapy [8,9,10,11,12], based on strong evidence for a number of effective medications in improving BMD and reducing fracture risk [74]. In particular, this review found that individuals who were aware of the diagnosis of osteoporosis [47, 65], those who believed they were susceptible to future fractures [59], or had previous evaluation of their bone health [47] had a preference for medications. Furthermore, patients with a good relationship with their healthcare provider were more likely to have a preference for pharmacotherapy [54, 59], and this may reflect a more patient-centred approach to communication and shared therapeutic decision-making. Despite this perceived need for pharmacotherapy, there are high rates of treatment non-adherence for osteoporosis, with an estimated 50% of patients not taking medications by 12 months [75]. Educating patients regarding the benefits and rationale for effective pharmacotherapies for osteoporosis, a largely asymptomatic condition in the absence of fracture, may help to improve patient adherence with therapies and health outcomes, particularly a reduction in fracture risk [76, 77]. This contrasts with other chronic musculoskeletal conditions such as osteoarthritis, low back pain and inflammatory arthritis, where the perceived need for pharmacotherapy is often driven by a desire for symptom and pain control and maintenance of function and mobility [24, 73, 78,79,80]. Furthermore, addressing patients’ concerns regarding pharmacotherapy, coupled with a broader approach to care that addresses lifestyle factors and support for effective self-management choices, may improve uptake of medications and health outcomes.

This review identified a number of patient beliefs regarding pharmacotherapy that may impact of adherence to osteoporosis pharmacotherapy. These included concerns regarding medication side effects, the potential for addiction and overdosing and the confusion and difficulty with the method of administration of medications [34, 36, 41,42,43, 45, 48, 53, 54, 60, 65, 66]. Furthermore, patients report a lack of knowledge about medications and they desire more health information [38, 43, 45, 48, 81, 82]. Medication non-adherence is also a growing concern in other chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease [83] and diabetes mellitus [84]. Poor adherence to medications is often multifactorial and may be due to patient, disease, medication, socioeconomic and healthcare system-related factors [85]. These areas of concern for osteoporosis pharmacotherapies may be addressed by multimodal interventions, including the provision of patient education and the development of novel systems to allow the mode of administration of medications to be more acceptable to patients and the use of technologies to prompt taking medications. Furthermore, the patients’ beliefs and preferences for pharmacotherapy reported by the included studies need to be contextualised by healthcare providers. These findings demonstrate the breadth of patients’ beliefs and preferences, and they may not apply to an individual patient. Clinicians should be cognisant of providing a tailored management approach to each specific patient, which may also improve the provider-patient relationship and foster a better therapeutic relationship.

Another finding from this review is that although some patients preferred medications [36, 37, 39, 48, 54, 56], they also perceived a need for lifestyle modifications and non-pharmacological therapies, such as exercise and vitamin supplementation to improve bone health [37, 38, 45, 57]. These non-pharmacological therapies were seen to be associated with lower-risk than prescription medications [38, 86]. Patients expressed dissatisfaction with the strong focus on pharmacotherapy from medical practitioners [48]. It appeared that driving the need for non-pharmacological therapies was the desire for a more holistic approach to healthcare management [36]. Despite exercise being a cornerstone therapy for the management of osteoporosis, a relatively smaller volume of literature was identified relating to patients’ needs regarding exercise. This represents an important area for future exploration given the under-utilisation of exercise among people with osteoporosis. Capitalising on this need may also improve the relationship between providers and patients and improve osteoporosis outcomes. Integrating the patients’ perceived needs of non-pharmacological management will improve guideline adherence, especially as these recommend [8,9,10,11,12], based on evidence [74, 87,88,89] the use of physical therapy and vitamin D and calcium supplementation in osteoporosis management. However, there is a paucity of data regarding patients’ perceived needs of other non-pharmacological lifestyle measures which may influence bone health, such as smoking cessation, attitudes to interventions related to falls prevention and avoidance of heavy alcohol: future research is required.

Clinical practice guidelines suggest the use of bone densitometry for the diagnosis of osteoporosis, to determine risk and need for therapy in people who have not sustained minimal trauma fractures [90]. This aligns with the findings of this review regarding the patients’ perceived need of investigations for osteoporosis for diagnostic evaluation, and also for ongoing surveillance of the efficacy of pharmacotherapy [36, 48, 53, 56]. Yet, in spite of this, previous studies have found low rates of investigation of bone health in high-risk patients [18], thus, underscoring a lost window of opportunity to improve the uptake and adherence to pharmacotherapy. However, these studies included mainly older female participants, known to be at increased risk of osteoporosis: whether these results are generalizable to the perceived need for investigations in male patients with osteoporosis and younger women are unknown.

This review needs to be interpreted in light of a number of limitations. First, the results of this review have been inferred from heterogeneous studies that evaluated different study questions and had different inclusion criteria for participants. Furthermore, the majority of included studies were conducted in English-speaking, developed countries and examined elderly females. Thus, the results may not be generalizable to men, younger populations or people of different ethnicities and economies. Although our search strategy encompassed both primary and secondary osteoporosis, there were no studies identified that examined other high-risk groups such as those with long-term glucocorticoid use, end-stage renal failure and other secondary causes of osteoporosis. Moreover, many of the included studies were susceptible to bias, particularly regarding participant recruitment and data collection, as more interested patients may be inclined to participate in these studies. Also, some studies that evaluated pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis were funded by the pharmaceutical industry and many others did not acknowledge sources of funding or state the influence of funding on the study outcomes. These limitations in study quality highlight a need for future high-quality studies to confirm the findings in this review to better understand the patient’s perceived needs for osteoporosis health services.

Despite these limitations, this review also has many strengths. A comprehensive scoping review was conducted across four complementary databases and included both qualitative and quantitative studies to capture the breadth of the existing literature. The rigorous and reproducible nature of our methods therefore aligns with the intent of a systematic literature review, demonstrating a notable strength in our approach compared to narrative scoping reviews. The inclusion of qualitative studies provides invaluable insight into patient beliefs and attitudes and is particularly suitable for exploring biopsychosocial paradigms. Furthermore, several common themes emerged from the included studies, irrespective of study design or study quality; thus, this triangulation of data adds weight to the validity and credibility of the data. Additionally, participants were drawn from across care settings: from the community, from both primary care settings and hospital settings.

This systematic scoping review has identified patients’ needs for improved health service delivery and better communication from healthcare professionals. Despite concerns regarding medication administration, side effects and compliance, patients have identified that osteoporosis pharmacotherapy is important. Patients also perceive a need for vitamin supplementation, exercise and ongoing surveillance of bone health. These findings may be unexpected given the low rates of screening and treatment for osteoporosis. Moving forward, the results from this review reinforce the need to improve the education provided not only to patients but also to cross-discipline healthcare practitioners regarding osteoporosis care. Workforce capacity building initiatives need to address the knowledge and skill deficits not only in pharmacologic management, including availability of different administration regimes for various therapies, but also important non-pharmacologic interventions like appropriate exercise and positive lifestyle choices. Given access limitations in many countries to medical specialists, capacity-building initiatives should be targeted in primary care settings. For consumers, education about the impact of osteoporosis and fractures remains critical to shift unhelpful nihilistic beliefs that the condition is an inevitable part of ageing and the risk-benefit balance of adherence of therapy. Their results confirm that clinicians need to provide patient-centred care through improved communication with patients, providing individualised information regarding the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis, encouraging multi-disciplinary shared care models and the use of decision aids to facilitate shared decision making. Moreover, given that poor treatment uptake is a significant practice gap in osteoporosis care, patient representatives should be involved in developing clinical practice guidelines and management initiatives to incorporate the patient perspective to develop patient-focused strategies, which may result in improved therapeutic relationships and compliance. The effects of this partnership will need to be evaluated to assess whether this ultimately translates into improved osteoporosis outcomes. These findings align well with the recent International Osteoporosis Foundation 2016 report [6], and together with the results from this review, provides important strategies for improving health services for people with bone health impairments from multiple perspectives, which are critical to consider in any system-level reform initiatives.

References

Watts J, Abimanyi-Ochom J, Sanders K (2013) Osteoporosis costing all Australians: a new burden of disease analysis - 2012 to 2022. The University of Melbourne, Australia

Van Staa T, Dennison E, Leufkens H, Cooper C (2001) Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 29(6):517–522

Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A (2007) Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res 22(3):465–475

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J et al (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

Si L, Winzenberg TM, Jiang Q, Chen M, Palmer AJ (2015) Projection of osteoporosis-related fractures and costs in China: 2010-2050. Osteoporos Int 26(7):1929–1937

Harvey NC, McCloskey EV (2016) Gaps and solutions in bone health. A global framework for improvement. International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon

Sanchez-Riera L, Carnahan E, Vos T, Veerman L, Norman R, Lim SS et al (2014) The global burden attributable to low bone mineral density. Ann Rheum Dis 73(9):1635–1645

Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S et al (2014) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25(10):2359–2381

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24(1):23–57

Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S et al (2010) Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 182(17):1864–1873

Wang M, Bolland M, Grey A (2016) Management recommendations for osteoporosis in clinical guidelines. Clin Endocrinol 84(5):687–692

Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, Greenspan SL, Harris ST, Hodgson SF et al (2010) American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract 16(Suppl 3):1–37

Mitchell P, Akesson K, Chandran M, Cooper C, Ganda K, Schneider M (2016) Implementation of models of care for secondary osteoporotic fracture prevention and orthogeriatric models of care for osteoporotic hip fracture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 30(3):536–558

Yates CJ, Chauchard MA, Liew D, Bucknill A, Wark JD (2015) Bridging the osteoporosis treatment gap: performance and cost-effectiveness of a fracture liaison service. J Clin Densitom 18(2):150–156

Sale JE, Beaton D, Posen J, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch E (2011) Systematic review on interventions to improve osteoporosis investigation and treatment in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 22(7):2067–2082

Kanis JA, Svedbom A, Harvey N, McCloskey EV (2014) The osteoporosis treatment gap. J Bone Miner Res 29(9):1926–1928

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35(5):293–305

Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, Beaton DE (2004) Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 15(10):767–778

Díez-Pérez A, Hooven FH, Adachi JD, Adami S, Anderson FA, Boonen S et al (2011) Regional differences in treatment for osteoporosis. The global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW). Bone 49(3):493–498

Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Lee SJ (2010) Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(4):650–657

Briggs AM, Chan M, Slater H (2016) Models of care for musculoskeletal health: moving towards meaningful implementation and evaluation across conditions and care settings. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 30(3):359–374

McLeod KM, Johnson CS (2011) A systematic review of osteoporosis health beliefs in adult men and women. J Osteoporos 2011:197454

Barker KL, Toye F, Lowe CJ (2016) A qualitative systematic review of patients’ experience of osteoporosis using meta-ethnography. Arch Osteoporos 11(1):33

Wluka AE, Chou L, Briggs AM, FM C (2016) Understanding the needs of consumers with musculoskeletal conditions: consumers’ perceived needs of health information, health services and other non-medical services: A systematic scoping review. MOVE muscle, bone & joint health

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8(1):19–32

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E (2011) ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health 33(1):147–150

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5:69–69

Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D (2004) Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:32–32

World, Health, Organisation, (WHO) http://www.who.int/topics/health_services/en/.Accessed 27 Oct 2016

Noblit G. HR. Meta-ethnography: synthesising qualitative studies. 1988 Sage Publications, California

Walsh D, Downe S (2005) Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 50(2):204–211

Critical Appraisal Skills Prgramme (CASP) (2014) CASP Checklists (http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists) Oxford. CASP

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C et al (2012) Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 65:934–939

Yu J, Brenneman SK, Sazonov V, Modi A (2015) Reasons for not initiating osteoporosis therapy among a managed care population. Patient Preference Adherence 9:821–830

Sale JEM, Hawker G, Cameron C, Bogoch E, Jain R, Beaton D et al (2015) Perceived messages about bone health after a fracture are not consistent across healthcare providers. Rheumatol Int 35(1):97–103

Besser SJ, Anderson JE, Weinman J (2012) How do osteoporosis patients perceive their illness and treatment? Implications for clinical practice. Arch Osteoporos 7(1–2):115–124

Bogoch E, Elliot-Gibson V, Escott B, Beaton D (2008) The osteoporosis needs of patients with wrist fracture. J Orthop Trauma 22(8 Suppl):S73–S78

Feldstein AC, Schneider J, Smith DH, Vollmer WM, Rix M, Glauber H et al (2008) Harnessing stakeholder perspectives to improve the care of osteoporosis after a fracture. Osteoporos Int 19(11):1527–1540

Fraenkel L, Gulanski B, Wittink D (2006) Preference for hip protectors among older adults at high risk for osteoporotic fractures. J Rheumatol 33(10):2064–2068

Gold D, Safi W, Trinh H (2006) Patient preference and adherence: comparative US studies between two bisphosphonates, weekly risedronate and monthly ibandronate. Curr Med Res Opin 22(12):2383–2391

Hansen C, Konradsen H, Abrahamsen B, Pedersen BD (2014) Women's experiences of their osteoporosis diagnosis at the time of diagnosis and 6 months later: a phenomenological hermeneutic study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 9:22438

Hiligsmann M, Dellaert B, Dirksen C, Van Der Qeijden T, Goemaere S, Reginster J et al (2014) Patients’ preferences for osteoporosis drug treatment: a discrete-choice experiment. Arthritis Res Ther 16(1):R36

Iversen MD, Vora RR, Servi A, Solomon DH (2011) Factors affecting adherence to osteoporosis medications: a focus group approach examining viewpoints of patients and providers. J Geriatr Phys Ther 34(2):72–81

Keen R, Jodar E, Iolascon G, Kruse H, Varbanov A, Mann B et al (2006) European women's preference for osteoporosis treatment: influence of clinical effectiveness and dosing frequency. Curr Med Res Opin 22(12):2375–2381

Lau E, Papaioannou A, Dolovich L, Adachi J, Sawka AM, Burns S et al (2008) Patients’ adherence to osteoporosis therapy: exploring the perceptions of postmenopausal women. Can Fam Physician 54(3):394–402

Martin A, Holmes R, Lydick E (1997) Fears, knowledge, and perceptions of osteoporosis among women. Drug Inf J 31(1):301–306

Mauck K, Cuddlhy M, Trousdale R, Pond G, Pankratz V, Melton LJ 3rd (2002) The decision to accept treatment for osteoporosis following hip fracture: exploring the woman's perspective using a stage-of-change model. Osteoporos Int 13(7):560–564

Mazor KM, Velten S, Andrade SE, Yood RA (2010) Older women’s views about prescription osteoporosis medication: a cross-sectional, qualitative study. Drugs Aging 27(12):999–1008

McKenna J, Ludwig AF (2008) Osteoporotic Caucasian and South Asian women: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ support. J R Soc Promot Heal 128(5):263–270 268p

Payer J, Cierny D, Killinger Z, Sulkova I, Behuliak M, Celec P (2009) Preferences of patients with post-menopausal osteoporosis treated with bisphosphonates--the VIVA II study. J Int Med Res 37(4):1225–1229

Richards J, Cherkas L, Spector T (2007) An analysis of which anti-osteoporosis therapeutic regimen would improve compliance in a population of elderly adults. Curr Med Res Opin 23(2):293–299

Rizzoli R, Brandi M, Dreinhofer K, Thomas T, Wahl D, Cooper C (2010) The gaps between patient and physician understanding of the emotional and physical impact of osteoporosis. Arch Osteoporos 5(1–2):145–153

Rothmann MJ, Huniche L, Ammentorp J, Barkmann R, Gluer CC, Hermann AP (2014) Women's perspectives and experiences on screening for osteoporosis (risk-stratified osteoporosis strategy evaluation, ROSE). Arch Osteoporos 9:192

Sale J, Beaton D, Sujic R, Bogoch E (2010) ‘If it was osteoporosis, I would have really hurt myself’. Ambiguity about osteoporosis and osteoporosis care despite a screening programme to educate fragility fracture patients. J Eval Clin Pract 16(3):590–596

Sale J, Bogoch E, Hawker G, Gignac M, Beaton D, Jaglal S et al (2014) Patient perceptions of provider barriers to post-fracture secondary prevention. Osteoporos Int 25(11):2581–2589

Sale J, Cameron C, Hawker G, Jaglal S, Funnell L, Jain R et al (2014) Strategies used by an osteoporosis patient group to navigate for bone health care after a fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 134(2):229–235

Sale J, Gignac M, Hawker G, Beaton D, Bogoch E, Webster F et al (2014) Non-pharmacological strategies used by patients at high risk for future fracture to manage fracture risk--a qualitative study. Osteoporos Int 25(1):281–288

Saltman D, Sayer G, O'Dea N (2006) Dosing frequencies in general practice--whose decision and why? Aust Fam Physician 35(11):915–919

Schousboe J, Davison M, Dowd B, Thiede Call K, Johnson P, Kane R (2011) Predictors of patients’ perceived need for medication to prevent fracture. Med Care 49(3):273–280

Scoville E, Ponce de Leon Lovaton P, Shah N, Pencille L, Montori V (2011) Why do women reject bisphosphonates for osteoporosis? A videographic study. PLoS ONE 6(4):e18468

Turbi C, Herrero-Beaumont G, Acebes J, Torrijos A, Grana J, Miguelez R et al (2004) Compliance and satisfaction with raloxifene versus alendronate for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in clinical practice: an open-label, prospective, nonrandomized, observational study. Clin Ther 26(2):245–256

Walliser J, Bolge S, Sen S (2006) Patients’ preference for osteoporosis medications: prefer-international. J Clin Rheumatol 12(4):S29

Weiss M, Vered I, Foldes A, Cohen Y, Shamir-Elron Y, Ish-Shalom S (2005) Treatment preference and tolerability with alendronate once weekly over a 3-month period: an Israeli multi-center study. Aging Clin Exp Res 17(2):143–149

Weiss T, McHorney C (2007) Osteoporosis medication profile preference: results from the PREFER-US study. Health Expect 10(3):211–223

Yood RA, Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Ermani S, Chan W, Kahler K (2008) Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med 23(11):1815–1821

Zanchetta J, Hakim C, Lombas C (2004) Observational study of compliance and continuance rates of raloxifene in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 65(6):470–480

Ringe JD, van der Geest SA, Moller G (2006) Importance of calcium co-medication in bisphosphonate therapy of osteoporosis: an approach to improving correct intake and drug adherence. Drugs Aging 23(7):569–578

Amonkar SJ, Dunbar AM (2011) Do patients and general practitioners have different perceptions about the management of simple mechanical back pain? Int Musculoskelet Med 33(1):3–7

Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, McLaughlin C, Fryer J, Smucker DR (1995) The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina back pain project. N Engl J Med 333(14):913–917

Otmar R, Reventlow SD, Nicholson GC, Kotowicz MA, Pasco JA (2012) General medical practitioners’ knowledge and beliefs about osteoporosis and its investigation and management. Arch Osteoporos 7:107–114

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F et al (2009) Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD003030

Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, Knight K, Hasselblad V, Gano A Jr et al (2002) Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness-which ones work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ 325(7370):925

Papandony MC, Chou L, Seneviwickrama M, Cicuttini FM, Lasserre K, Teichtahl AJ et al (2017) Patients’ perceived health service needs for osteoarthritis (OA) care: a scoping systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil 25:1010–1025

Body JJ, Bergmann P, Boonen S, Boutsen Y, Devogelaer JP, Goemaere S et al (2010) Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: a consensus document by the Belgian bone Club. Osteoporos Int 21(10):1657–1680

Weycker D, Macarios D, Edelsberg J, Oster G (2006) Compliance with drug therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17(11):1645–1632

Kastner M, Straus SE (2008) Clinical decision support tools for osteoporosis disease management: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med 23(12):2095–2105

Winzenberg T, Oldenburg B, Frendin S, De Wit L, Riley M, Jones G (2006) The effect on behavior and bone mineral density of individualized bone mineral density feedback and educational interventions in premenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial [NCT00273260]. BMC Public Health 6:12

Jensen AL, Lomborg K, Wind G, Langdahl BL (2014) Effectiveness and characteristics of multifaceted osteoporosis group education--a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 25(4):1209–1224

Laliberte MC, Perreault S, Jouini G, Shea BJ, Lalonde L (2011) Effectiveness of interventions to improve the detection and treatment of osteoporosis in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 22(11):2743–2768

Smith CA (2010) A systematic review of healthcare professional-led education for patients with osteoporosis or those at high risk for the disease. Orthop Nurs 29(2):119–132

French MR, Moore K, Vernace-Inserra F, Hawker GA (2005) Factors that influence adherence to calcium recommendations. Can J Diet Pract Res 66(1):25–29

Sale JE, Beaton DE, Sujic R, Bogoch ER (2010) ‘If it was osteoporosis, I would have really hurt myself’. Ambiguity about osteoporosis and osteoporosis care despite a screening programme to educate fragility fracture patients. J Eval Clin Pract 16(3):590–596

Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS (2009) Medication adherence. Its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation 119(23):3028–3035

Krass I, Schieback P, Dhippayom T (2015) Adherence to diabetes medication: a systematic review. Diabet Med 32(6):725–737

World Health Organisation (2003) Adherence to long-term therapy: evidence for action Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publicationsadherence_introduction.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2016

Lau E, Papaioannou A, Dolovich L, Adachi J, Sawka AM, Burns S et al (2008) Patients’ adherence to osteoporosis therapy: exploring the perceptions of postmenopausal women. Can Fam Physician 54:394–402 399p

Body JJ, Bergmann P, Boonen S, Boutsen Y, Bruyere O, Devogelaer JP et al (2011) Non-pharmacological management of osteoporosis: a consensus of the Belgian bone Club. Osteoporos Int 22(11):2769–2788

Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ, Downie F, Murray A, Ross C, et al. (2011) Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (7):CD000333

Kemmler W, Haberle L, von Stengel S (2013) Effects of exercise on fracture reduction in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 24(7):1937–1950

Kanis J, McCloskey E, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster J (2012) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24(1):23–57

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This work was performed in partnership with Move: muscle, bone and joint health and was supported by a partnership grant awarded by the organisation. L.C is the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award and Arthritis Foundation Scholarship. A.E.W is the recipient of a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (Clinical Level 2 #1063574). AMB is the recipient of a NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (#1132548).

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chou, L., Shamdasani, P., Briggs, A.M. et al. Systematic scoping review of patients’ perceived needs of health services for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 28, 3077–3098 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4167-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4167-0