Abstract

Summary

This study used in-depth interviews and focus groups to evaluate osteoporosis care after a fracture. Patients (eligible women aged 67 who sustained a clinical fracture(s)), clinicians, and staff stated that an outreach program facilitated osteoporosis care management, but more-tailored education and support and increased participation of orthopedic specialists appear necessary.

Introduction

Osteoporosis treatment reduces fracture risk, but screening and treatment are underutilized, even after a fracture has occurred. This study evaluated key stakeholder perspectives about the care of osteoporosis after a fracture.

Methods

Participants were from a nonprofit health maintenance organization in the United States: eligible women members aged 67 or older who sustained a clinical fracture(s) (n = 10), quality and other health care managers (n = 20), primary care providers (n = 9), and orthopedic clinicians and staff (n = 28); total n = 67. In-depth interviews and focus groups elicited participant perspectives on an outreach program to patients and clinicians and other facilitators and barriers to care. Interviews and focus group sessions were transcribed and content-analyzed.

Results

Patients, clinicians, and staff stated that outreach facilitated osteoporosis care management, but important patient barriers remained. Patient knowledge gaps and fatalism were common. Providers stated that management needed to begin earlier, and longer-term patient support was necessary to address adherence. Orthopedic clinicians and staff expressed lack of confidence in their osteoporosis management but willingness to encourage treatment.

Conclusions

Although an outreach program assisted with the management of osteoporosis after a fracture, more-tailored education and support and increased participation of orthopedic specialists appear necessary to maximize osteoporosis management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common condition that results in substantial morbidity and mortality [1]. It is found in nearly 20% of women over the age of 65, many of whom will suffer subsequent fractures, disability, and diminished quality of life [2]. While treatment reduces fracture risk, screening and treatment are under-utilized, even after a fracture has occurred [3]. Although a number of strategies have been found to be effective in prompting patients and clinicians to improve osteoporosis care management after a fracture, the effect sizes of interventions to date have been modest [4–7]. For example, among members of a large health maintenance organization (HMO) in the United States (US), a patient-specific electronic medical record (EMR) prompt to the primary care provider (PCP) led to 51.5% of post-fracture patients receiving osteoporosis management (a bone mineral density (BMD) measurement or osteoporosis treatment) in the 6-month post-fracture, as compared to 6% in the usual care group [4–7]. The later implementation of this approach along with a centralized patient outreach resulted in 44% of patients receiving osteoporosis care management by the end of the study, leaving more than half of patients without clear management [8].

To achieve further improvements in care, future interventions will need to incorporate components that address the barriers that patients and staff have to osteoporosis management. While a number of patient barriers to osteoporosis management have been described [9, 10], only a few studies have attempted to integrate those findings with the views, roles, and preferences of the clinical staff involved in osteoporosis care [11]. Following implementation of the outreach program described above [8], the study we report on here conducted focus groups and individual interviews with patients, PCPs, orthopedic clinicians and staff, and managers to evaluate the outreach program. The focus groups and interviews elicited barriers and facilitators to screening and treating osteoporosis, perceived utility of the outreach program, and overall advice on how to improve screening and treatment of osteoporosis. Our study’s immediate goal was to use the findings reported here to improve the outreach program in the future, with the long-term goal of improving osteoporosis care and fracture prevention.

Materials and methods

Setting

Qualitative evaluation of the outreach program was conducted at a non-profit, group-model HMO in the Pacific Northwest US with about 485,000 members and an electronic medical record. Demographic characteristics of the HMO members are similar to those of the area population [12]. The protocol for this evaluation was approved by the HMO’s Institutional Review Board, and participants provided written informed consent.

Outreach program

The outreach to PCPs and patients was designed to improve the care of osteoporosis after a fracture [8]. PCPs with eligible patients were sent patient-specific EMR messages by a physician’s assistant or registered nurse operating under a protocol. The message informed the PCP that the patient had a fracture; suggested follow-up, citing a guideline recommendation; and offered to follow up with the patient on the PCP’s behalf. The follow-up, if requested, utilized mailings and one–two phone calls to encourage and initiate osteoporosis screening and/or treatment. A care summary then was sent to the PCP, who provided further follow-up as necessary.

The outreach program led to increases in the frequency of BMD measurement and osteoporosis medication dispensing, but the effect varied among important subgroups. For example, older patients were less likely than younger patients to be treated [8].

Design of qualitative program evaluation

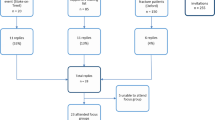

Family practice and internal medicine PCPs and orthopedic providers were recruited for the program evaluation using a stratified sampling method. Table 1 summarizes the participant data collection method, including participation rates. We recruited PCPs from a list of 24 providers who had at least ten patients enrolled in the outreach program. We recruited orthopedic providers from a list of 35 that included individuals with different types of professional certification, levels of practice, and locations worked in order to obtain diverse perspectives. We also sought to interview health plan leadership with quality improvement responsibility and experience representing a range of geographic areas (from a group of eight individuals), and the five staff who performed the patient outreach. Scheduling conflicts were the primary reason for PCPs, orthopedic providers, and managers/health plan leaders to decline participation in the interviews or focus groups.

We completed nine semi-structured, in-depth individual interviews with primary care physicians (37.5% approached participated) and five with key managers (62.5% approached participated). We also conducted six focus groups: four among orthopedists and allied staff members (n = 28) (80% approached participated); one with the members of the osteoporosis outreach team (n = 5) (100% participation); and another with members of an osteoporosis quality improvement committee (n = 10) (55.5% participation). A total of 57 staff were included—29 physicians, five allied health providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants), 12 registered nurses, one pharmacist, and ten other staff.

We completed ten semi-structured, in-depth patient interviews. We used a purposeful sampling method to recruit patients who were age 67 or older, had a fracture but no BMD measurement or osteoporosis treatment in the prior 12 months, and had participated in the outreach program. We attempted to balance participants on age (67–75 and 76) and whether they had accepted or declined the referral/advice offered during the outreach. Utilizing a letter and follow-up phone call, we recruited from a list of 34 eligible participants (29.4% approached participated). Primary reasons for participants not being interviewed included feeling unwell, uninterested, and unreachable by phone.

Data collection and analysis methods

Interview guides were developed by the research team based upon their prior experience [4, 8, 13, 14] and a literature review. Using a standard qualitative technique, the research team refined the guides for relevancy and utility following the first few interviews. The interview guides elicited barriers and facilitators to screening and treating osteoporosis, the perceived utility of the outreach program, and overall advice on how to improve screening and treatment of osteoporosis. Interviews and focus groups were conducted by two of the authors (AF and JS) trained in qualitative research [15, 16], tape-recorded, and professionally transcribed for analysis. We aimed to interview each stakeholder group until we elicited no new content [17]. To analyze the transcripts, we used standard qualitative methods [18, 19] that focused on representing, describing, and interpreting the data. A coding dictionary was developed by marking passages of text with codes indicating the content of the discussions. Coded text was reviewed through an iterative process, resulting in refined themes [19, 20]. A qualitative research software package, ATLAS.ti 5.0 (Scientific Software Development, 1997), was used to electronically code and manage data and to generate reports of coded text for analysis.

Results

Patient barriers to the management of osteoporosis

We compared PCP and patient perceptions of patient barriers to osteoporosis management. Their views were highly concordant and highlight several management challenges. These common themes, along with key findings, are summarized in Table 2.

PCPs noted, and patients demonstrated, a lack of patient understanding of osteoporosis and its management, especially when compared to other common conditions. PCPs and patients stated that the confusion of osteoporosis with osteoarthritis promotes the idea that osteoporosis is an inevitable and benign consequence of aging. PCPs and patients noted strong media influence on patient perceptions of osteoporosis. PCPs noted that the popular press increased demand for frequent and perhaps unwarranted bone mineral density screening.

Patients who had received medication desired more information about their medication and were concerned about the long lists of drug side effects in advertisements. PCPs perceived that patients often had concerns/complaints about side effects from bisphosphonates and supplements. PCPs stated that side effects and challenging medication routines led to compliance problems in excess of those seen with other chronic medications and stated the need for assistance with ensuring compliance. Patients expressed confusion about how long they needed to take their medications and what might happen if they stopped. Even after having received the outreach, they desired more follow-up to address these areas.

Interestingly, PCPs and patients stated that neither medication cost nor transportation needs for BMD measurement were major barriers for screening or treatment compliance.

PCPs highlighted the unique challenges in addressing osteoporosis in younger versus older post-menopausal women. Fatalism, or the sense that finding osteoporosis and treating it would not be worthwhile, was noted to be prevalent among very old (age 80) patients. This contrasted with more active involvement among younger participants, who were more interested in prevention and generated more demand for osteoporosis screening. PCPs expressed frustration with the time required to deal with younger women’s demand for screening in excess of guideline recommendations.

Patient-noted facilitators of osteoporosis management

Interviews with patients also explored potential osteoporosis management facilitators. Patients of all ages expressed more willingness and comfort with taking supplements (calcium and vitamin D) than prescription medication for osteoporosis. Patients appreciated the assistance they received with transportation from friends and family, and the inexpensive and convenient medical transport options to obtain screening exams and medications.

Patients’ trust in PCP advice and information from the health plan facilitated osteoporosis management. Also, patients noted that tips for routinizing medication use, such as using triggers (e.g., meals, calendars, placement of medications) to remember when to take medications, facilitated long-term adherence. Younger patients (aged 67–75) were more likely to say they wanted to live a long and active life, acquire health information, and understand osteoporosis and its prevention. These younger patients were more likely than older patients to describe lifelong involvement in activities to promote health and wellness, such as exercising regularly, eating nutritionally, and applying a “sensible” or “practical” approach to all aspects of their health. Additionally, younger patients were more likely to have an understanding of osteoporosis and related risk factors. These attributes seemed to serve as facilitators to disease management.

Health system barriers to the management of osteoporosis

We compared PCP and orthopedic specialist perspectives of health system barriers to the management of osteoporosis. Common themes, along with key findings, are summarized in Table 3. Both PCPs and specialists said they have severe time constraints for addressing osteoporosis risk during acute care visits and need safety net approaches to ensure needed care. PCPs cited the impact of multiple competing health needs, and orthopedists wondered, given their high-volume acute fracture load, how they would find the time to research patients’ osteoporosis status and obtain the additional training they need to understand osteoporosis screening and treatment. Since a broad array of screening tests is relevant to osteoporosis, PCPs and orthopedists cited difficulty in efficiently finding relevant DXA and laboratory results in the medical record. Orthopedists noted that they were particularly unpracticed in interfacing with the EMR tools that might assist them.

PCPs and orthopedists agreed that numerous osteoporosis management gaps result during the transition from specialty to primary care when an older patient has a fracture. Orthopedists note that they see patients for acute needs—to address the fracture, not the potential underlying cause of osteoporosis. PCPs expressed frustration with the long delay or “missed opportunity” in addressing osteoporosis after a fracture, which results from their not seeing patients until many months later (if ever).

Although most orthopedists believe they need to take a more active role in osteoporosis management, they agreed that this is not happening consistently. Some expressed the view that orthopedists are trained to do surgery and that their role should be limited to that. Orthopedists expressed lack of confidence in many aspects of osteoporosis care. PCPs stated that they would welcome the initiation of at least BMD screening by specialists at the time of a fracture and noted that bisphosphonates could be prescribed then also because of their lack of interaction with other medicines.

Orthopedic specialists were uncomfortable with ordering something (e.g., a laboratory test or medication) because they might be expected to follow up on the results (i.e., the “system” would label them as the responsible party for the tests and medications). Orthopedists were especially concerned about having to assume the management of patients who do not have an assigned PCP.

Several orthopedists expressed frustration that osteoporosis was not detected and treated in advance of a fracture. Many stated that when they became involved it was “too late.”

Even when orthopedists became involved early with osteoporosis management, they stated that communication with PCPs was suboptimal. Specialists stated that part of the problem was finding the most effective and quickest ways to relay information. While PCPs expressed a strong desire for specialists to play a greater and more consistent role in osteoporosis, some orthopedists were concerned that this might be perceived as PCP “territory infringement.” Another specialist concern was that an already overburdened primary care system could not absorb their referrals for follow-up.

PCPs stated that they were not comfortable with determining who might benefit most from the treatment for osteoporosis. Orthopedists stated that they recognized this issue among PCPs.

Both groups acknowledged inconsistent management (e.g., neither type of clinician consistently ordered a DXA in certain situations) and a bias against treating elderly patients because of a general tendency to believe that nothing can be done for them. Both types of clinician also mentioned the lack of easy access to information about osteoporosis, in particular, confusion about the utility of vitamin D to prevent and treat osteoporosis.

System facilitators of osteoporosis management

All interviewees provided input on current system supports and recommendations for improving care systems for osteoporosis in the future. These findings are highlighted in Table 4. Respondents agreed that the outreach program addressed the difficulties with transition from specialty to primary care after a fracture. It served to provide patients with timely counseling and management, and it reduced care variation while reducing the burden on PCPs. Efficiencies could be realized by sharing best practices among outreach workers, standardizing operating procedures, and encouraging creative use of staff. Respondents strongly recommended that managers expect and plan for long-term sustainability and consistently fund the outreach program. Interviewees supported broadening the scope of outreach to include longer-term follow-up with medication compliance and patient concerns.

All respondents advocated for standardized protocols for integrating and involving specialists (orthopedists, fracture clinic staff, radiologists, emergency staff) in the management of osteoporosis at the time of fracture. Most stated that specialists should provide basic education in osteoporosis and initiate screening or treatment, with follow-up by a PCP or care manager.

Besides the EMR data, Web-based guidelines and pre-grouped orders and alerts in the EMR were perceived as useful. Specialists were less accustomed to using these tools, so they were less confident about their ability to use them in their practice. All clinicians advocated keeping electronic tools simple and accessible.

Several other recommendations addressed provider and patient education. Most interviewees stated that PCPs and key specialists should receive ongoing education in osteoporosis treatment, interpretation of DXA results, and efficient and effective ways to monitor and treat secondary causes of osteoporosis (such as Vitamin D deficiency). Respondents perceived a need for patient information on osteoporosis prevention and management. PCPs and specialists strongly endorsed expanding patient support to primary prevention. Although during the outreach program clinicians could request that an osteoporosis educational packet be mailed to patients, among clinicians there were gaps in awareness and follow-through on its use. Clinicians stated that they would benefit from being prompted to provide educational information, or it should be sent out automatically. More educational opportunities for patients, such as classes or chat room/Internet support, would be valuable too.

In summary, our analyses of responses from providers and patients revealed common perceptions regarding patient barriers to osteoporosis care, including gaps in patient knowledge and understanding of osteoporosis, generational differences in patient needs and approaches, and the influence that the media has upon medication use. Another common theme was the challenge of adhering to bisphosphonates due to the routine required and the side effects.

Patient interviews revealed several facilitators of care: positive orientation toward the use of supplements and vitamins; social support; adherence, based on engaging in medication routines and trusting the health care provider/system; and the patient having a proactive approach to health.

Common themes emerging from the comparison of PCP and orthopedic specialist views of barriers to care included lack of time during visits, difficulty accessing records, care management gaps in the transition from specialty to primary care, and integration issues between specialty and primary care. As facilitators of care, clinicians and managers endorsed the effectiveness and utility of the outreach program, Web-based osteoporosis clinical guidelines, EMR tools, and patient education materials. Staff provided advice on areas for future quality improvement: better integration of specialist and primary care roles in osteoporosis care, improved methods for efficient retrieval and follow-up on osteoporosis-related patient evaluations, more clinician education, and several methods to optimize patient outreach programs.

Discussion

Findings from our focus groups and interviews with patients, PCPs, orthopedic clinicians and staff, and managers yielded their perceptions of the clinician and patient outreach program implemented at our HMO to improve osteoporosis management after a fracture [8]. In general, respondents said that the osteoporosis outreach program overcame many of the problems that are typically associated with the transition from specialty to primary care after a fracture. For example, they said the outreach program relieved the follow-up burden on already overburdened practitioners and largely overcame post-fracture patients getting “lost” in the system. Given that the program was effective in improving care [8] and also was well received, we would recommend broad implementation of similar post-fracture osteoporosis outreach programs.

Respondents also described their perceptions of remaining challenges to, and facilitators of, more-effective secondary prevention of osteoporosis. Their advice should be integrated into future osteoporosis quality improvement initiatives. Respondents stated that the need for outreach would diminish if orthopedic and other specialists who treat acute fractures could initiate osteoporosis management through referral, screening, and/or treatment. They also said that specialists likely would need leadership motivation, cultural change, and additional training to encourage their most effective participation. Respondents stated that useful additions to clinical practice would be administrative and workflow supports to encourage orthopedists’ participation in prevention (such as EMR enhancements and training) tailored to the needs of diverse sites.

Our findings are of particular consequence with regard to using electronic health records for patient management. Our HMO has a longstanding (>10 years) and well-integrated EMR; yet, many clinicians report not being adequately facile with accessing patient clinical information. Further inquiry related to ease of use of EMR tools and their integration into clinical care may yield important insights to enhance the usefulness of this technology.

Practitioners highlighted several specific needs related to guideline clarification and training: DXA interpretation; clarification of and counseling techniques for the risks and benefits of treatment, especially in the very old; and vitamin D management. This information should be useful to health care providers and specialty societies planning communication and educational opportunities. Patients and providers supported the need for additional patient outreach and education to ensure understanding and to assist with medication adherence. Given that adherence to osteoporosis medication is generally poor [21], program enhancement in this area is sorely needed to achieve anticipated fracture prevention outcomes.

Our findings mirror those of a Canadian study, the findings of which support the need for a larger role for orthopedists, improved integration of acute fractures, and follow-up osteoporosis care [11]. Others have also supported the need for enhanced provider training [22, 23] and patient education [9, 10, 24] to move past the osteoporosis-osteoarthritis confusion and to enhance understanding of osteoporosis concepts.

This study has limitations. The findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Our study site is a large group practice where physicians are salaried, and physicians in private practice may receive more financial incentives to complete osteoporosis evaluation and treatment. Views of respondents may have differed from those of non-responders, resulting in bias in our findings. However, our response rate to recruitment was reasonable (especially for managers and specialists), diminishing this concern. Respondents were recipients of, or involved in, the outreach program; thus, participants’ views may differ from those of individuals without this experience. The original outreach program targeted women included in the United States National Center for Quality Assurance, HEDIS (Health Employer Data and Information Set) quality improvement measure for post-fracture management of osteoporosis. (www.ncqa.org/tabid/346/Defaut.aspx). We, therefore, included women aged 67 or older—younger women and men were not included. Also, the cultural context we found, one of valuing the EMR and care management, may vary significantly by care setting. However, given the pervasive care gaps found in the post-fracture management of osteoporosis [3], the transition problems described are likely common to most models of care.

More research is needed to develop and evaluate improved systems for osteoporosis care to respond to the particular needs of the many types of involved stakeholders. In particular, it would be useful to more fully differentiate the needs of younger and older women from men at risk and create tailored intervention programs. Other possible fruitful interventions to evaluate might include strengthening inpatient and outpatient fracture clinic and emergency room protocols to address osteoporosis management, providing more osteoporosis education to orthopedists during their training and as continuing medical education, developing and strengthening electronic medical record-based decision support for osteoporosis for PCPs and specialists, and expanding patient support to primary prevention.

In conclusion, we believe most of the findings we have highlighted are generalizable and that implementation of similar outreach with enhancements based on the qualitative findings could broadly improve care. Our findings are especially important when viewed within the context of the increasing pressure for health care providers to address gaps in guideline-based care. The findings from this study should be useful to other health care organizations planning osteoporosis quality improvement activities.

References

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2000) Physicians guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359:1761–1767

Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, Beaton DE (2004) Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 15:767–778

Feldstein AC, Elmer PJ, Smith DH, Herson M, Orwoll E, Chen C, Aickin M, Swain MC (2006) Electronic medical record reminder improves osteoporosis management after a fracture: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:450–457

Gardner MJ, Brophy RH, Demetrakopoulos D, Koob J, Hong R, Rana A, Lin JT, Lane JM (2005) Interventions to improve osteoporosis treatment following hip fracture. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:3–7

Majumdar SR, Rowe BH, Folk D, Johnson JA, Holroyd BH, Morrish DW, Maksymowych WP, Steiner IP, Harley CH, Wirzba BJ, Hanley DA, Blitz S, Russell AS (2004) A controlled trial to increase detection and treatment of osteoporosis in older patients with a wrist fracture. Ann Intern Med 141:366–373

Bliuc D, Eisman JA, Center JR (2006) A randomized study of two different information-based interventions on the management of osteoporosis in minimal and moderate trauma fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1309–1317

Feldstein AC, Vollmer WM, Smith DH, Petrik A, Schneider J, Glauber H, Herson M (2007) An outreach program improved osteoporosis management after a fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:1464–1469 [Epub 2007 Jul 30]

Ali NS, Twibell KR (1994) Barriers to osteoporosis prevention in perimenopausal and elderly women. Geriatr Nurs 15:201–205

Burgener M, Arnold M, Katz JN, Polinski JM, Cabral D, Avorn J, Solomon DH (2005) Older adults’ knowledge and beliefs about osteoporosis: results of semistructured interviews used for the development of educational materials. J Rheumatol 32:673–677

Jaglal SB, Cameron C, Hawker GA, Carroll J, Jaakkimainen L, Cadarette SM, Bogoch ER, Kreder H, Davis D (2006) Development of an integrated-care delivery model for post-fracture care in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int 17:1337–1345

Freeborn DK, Pope C (1994) Promise and performance in managed care: the prepaid group practice model

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE (2008) A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, March, In Press

Feldstein AC, Elmer PJ, Orwoll E, Herson M, Hillier T (2003) Bone mineral density measurement and treatment for osteoporosis in older individuals with fractures: A gap in evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med 163:2165–2172

Erlandson DA, Harris EL, Skipper BL, Allen SD (1993) Doing naturalistic inquiry: a guide to methods

Marshall C, Rossman GB (1995) Designing Qualitative Research. 2nd Edn

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry

Lofland l, Lofland J (1995) Analyzing Social Settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis. 3rd Edn

Wolcott HF (1994) Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis, and Interpretation

Strauss AL, Corbin JM (1990) Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques

Ettinger B, Pressman AR, Schein J, Chan J, Silver P, Connolly N (1998) Alendronate use among 812 women: Prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints, non-compliance with patient instructions, and discontinuation. J Manag Care Pharm 4:488–492

Jaglal SB, McIsaac WJ, Hawker G, Carroll J, Jaakkimainen L, Cadarette SM, Cameron C, Davis D (2003) Information needs in the management of osteoporosis in family practice: an illustration of the failure of the current guideline implementation process. Osteoporos Int 14:672–676

Jaglal SB, Carroll J, Hawker G, McIsaac WJ, Jaakkimainen L, Cadarette SM, Cameron C, Davis D (2003) How are family physicians managing osteoporosis? Qualitative study of their experiences and educational needs. Can Fam Physician 49:462–468 462–68

Blalock SJ, Currey SS, DeVellis RF, DeVellis BM, Giorgino KB, Anderson JJ, Dooley MA, Gold DT (2000) Effects of educational materials concerning osteoporosis on women’s knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. Am J Health Promot 14:161–169

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Martha Swain for editorial support and Debra Burch and Chalinya Bruce for secretarial support.

This study was supported in part by a research contract from Merck & Co., Inc.

This study was presented at the 13th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, March 19–21, 2007, Portland, Oregon, and the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research Meeting, September 16–19, 2007, Oahu, Hawaii.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclaimers: This study was supported in part by a research contract from Merck & Co., Inc. The sponsor had no role in the study design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Dr. Feldstein has received research grant support from Merck & Co, Inc.; Amgen; and Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Vollmer has served on ad hoc advisory boards for Merck and Co., Inc., and is director of the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) Operations Center, funding for which includes unrestricted educational grants to his employer, the Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, ALTANA, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Chiesi, and Merck. Dr. Smith has received research grant support from Sanofi-Aventis, Abbot, Amgen, and Genzyme.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feldstein, A.C., Schneider, J., Smith, D.H. et al. Harnessing stakeholder perspectives to improve the care of osteoporosis after a fracture. Osteoporos Int 19, 1527–1540 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0605-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0605-3