Abstract

Background

Little is known about first-fill adherence rates for diabetic medications and factors associated with non-fill.

Objective

To assess the proportion of patients who fill their initial prescription for a diabetes medication, understand characteristics associated with prescription first-fill rates, and examine the effect of first-fill rates on subsequent A1c levels.

Design

Retrospective, cohort study linking electronic health records and pharmacy claims.

Participants

One thousand one hundred thirty-two patients over the age of 18 who sought care from the Geisinger Clinic, had Geisinger Health Plan pharmacy benefits, and were prescribed a diabetes medication for the first time between 2002 and 2006.

Measurements

The primary outcome of interest was naïve prescription filled by the patient within 30 days of the prescription order date.

Results

The overall first-fill adherence rate for antidiabetic drugs was 85%. Copays < $10 (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.57–3.14) and baseline A1c > 9% (OR 2.63, 95% CI 1.35, 5.09) were associated with improved first-fill rates while sex, age, and co-morbidity score had no association. A1c levels decreased among both filling and non-filling patients though significantly greater reductions were observed among filling patients. Biguanides and sulfonylureas had higher first-fill rates than second-line oral agents or insulin.

Conclusions

First-fill rates for diabetes medication have room for improvement. Several factors that predict non-filling are readily identifiable and should be considered as possible targets for interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Much of the distance between the promise of evidence-based medicine and reality of improved patient outcomes can be attributed to problems in the ‘last mile,’ or patient adherence—the “extent to which a person’s behavior coincides with medical or health advice.”1 Prescription medication adherence is strongly associated with outcomes for a number of chronic diseases.2,3 Most of the evidence, however, is based on follow-up studies of patients who have filled their first prescription; relatively little is known about the percent of prescriptions that are never filled and the impact of overall first-fill non-adherence on disease outcomes. Similarly, factors associated with non-fill have yet to be explored.

Quantifying first-fill prescription rates, the procurement of the first prescribed medication for a disease following a written order, is especially challenging. Efforts to improve prescription adherence are increasing among health plans and pharmacy benefits managers. Most strategies are confined to individuals who fill at least one prescription in the therapeutic class of interest.4 This constraint is inherent to systems that manage adherence programs because awareness of a prescription is limited to claims data (i.e., data are only available when a claim for a prescription is processed), meaning when the drug was actually picked up by the patient. Thus, the denominator for evaluating treatment adherence is based on the group that first fills its prescription, not the group that is first prescribed a drug in a specific class. Access to electronic health record data (i.e., the patient’s medical record) provides the means to identify all patients who were first prescribed a medication, whether or not a claim was processed. Studying and intervening upon first-fill rates may impact the field differently than focusing on standard adherence measures such as the medication possession ratio.

We examined first-fill rates for patients treated with diabetes medications by linking prescribing information from electronic health records (EHR) to pharmacy claims data of one insurer. By using information from EHR and pharmacy claims, one can identify prescriptions that were written, but not filled by the patient. We used a retrospective cohort design to assess the proportion of patients who filled a naïve prescription for antihyperglycemic medications, to understand characteristics associated with first-fill rates, and to examine the effect of first-fill rates on attainment of hemoglobin A1c goals.

METHODS

Setting

Geisinger Clinic’s EHR and Geisinger Health Plan’s (GHP) claims database were the primary sources of data for this study. Geisinger is a diversified health care system encompassing the Geisinger Clinic, a multi-specialty practice that has 57 clinic sites and 730 employed physicians and physician’s assistants. The Geisinger Clinic patient population includes residents from central and northeastern Pennsylvania, a predominantly white population (96% Caucasian). The Epic Systems Corporation® EHR system was installed in all Geisinger Clinic community practice sites and specialty clinics from 1996 through 2001 and to date contains information on nearly three million patients. This system allows for the integration of clinical information across diverse settings of care and makes all patient information available in digital form. Geisinger Clinic patients are represented by a range of different payers, including GHP which accounts for 30% of the Clinic patients. Though GHP shares its name with Geisinger, it is an independent entity and one of the nation’s largest rural HMOs.

Study Sample

The following were the criteria of th study patients: 1) age 18 or older; 2) seeking care from the Geisinger Clinic; 3) had Geisinger Health Plan pharmacy benefits; and 4) prescribed their first antihyperglycemic medication between January 2002 and December 2006 (n = 1,173). Antihyperglycemic drugs were defined in the following classes: meglitinides, sulfonylureas, insulin, biguanides (metformin), thiazolidinediones, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, lipase inhibitors, pramlintide, GLP-1 receptor agonists (including exenatide). To eliminate patients who may fill their prescription using a prescription plan other than GHP (e.g., spousal pharmacy benefits), the analysis was limited to those who had used their GHP pharmacy benefit at any time prior to the date of the index medication (n = 1,132). Furthermore, we limited inclusion to patients who had been enrolled in GHP for at least one year prior to the index prescription, to further limit the sample to incident diabetics.

Study Variables

The following data were extracted from the EHR: age, sex, date of diabetes diagnosis (i.e., defined using relevant ICD-9 codes from medications or problems lists), number of refills written on the index diabetes prescription (i.e. first antihyperglycemic prescription), drug class, number of co-morbid conditions (other than HIV due to IRB restrictions) for a calculated Charlson Index5, number of office visits within 6 months prior to index prescription, all A1c lab results (continuous measure and dichotomized as < 9% or 9%+, total number of medications prescribed +/− 10 days of index prescription, and date of order of the medication. In cases where patients were prescribed multiple medications on the index date, all prescriptions were included in analysis.

The following data were collected from the pharmacy claims database: drug class, copay amount (actual patient out-of-pocket costs defined as $0–10 or > $10), order date (i.e., the date the prescription was ordered), whether the prescription was filled, and if so, the fill date. Identifiers from the EHR record were linked to GHP pharmacy data files.

Analysis

Because less than 1% of prescriptions were filled beyond 30 days, a patient was designated as having first-filled if the prescription was claimed within 30 days of the EHR order date. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to examine time until prescription first-fill and to stratify estimates by patient characteristics (log-rank test). The primary outcome of adherence was based on patients who were classified as either fillers or non-fillers. Univariate analysis was conducted to determine which characteristics were related to first-fill. Skewed continuous data were categorized prior to univariate analyses. Categorical and ordinal variables were analyzed using Chi-Square tests, Fisher’s exact test, and Cochran Armitage trend tests. Continuous variables were assessed using t-tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests, where appropriate. A multiple logistic regression model was conducted to determine those variables that independently predicted first-fills. Variables were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model when bivariate p-values were less than 0.15. The final model was developed using a backwards selection process and the decision to retain covariates was based on both improvement on model fit and scientific plausibility.6 All two-way interactions of retained covariates were examined. As a secondary analysis and validation of the methods, change in A1c was compared between fillers and non-fillers. For this analysis, two-sample t-tests were used to compare baseline A1c (value occurring closest to but before and within 6 months of initial order), follow-up A1c (value occurring closest to but within 31–365 post order), and the change in A1c (difference between baseline and follow-up, limited to those patients who had both values). Analyses were conducted with the SAS statistical software package version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

There were 1,132 patients who met all inclusion criteria. Of this sample, 57% (649) were women and 95% (1077) were Caucasian. The median age was 49 years. Biguanides and sulfonylureas constituted 90% of all naïve prescriptions, reflecting the standard practice of initiating antihyperglycemic therapy with these first-line agents (Table 1).

First-fill Rates and Associated Factors

Overall, 85% (962) of patients filled their naïve prescriptions within a 30-day period, most within 5 days of the prescription date. Copays of less than $10 resulted in a first-fill rate of 89%; copays greater than $10 resulted in a 77% fill rate (p = 0.001, Table 1). In a multivariate model, prescriptions with copays less than $10 were over twice as likely to be filled than prescriptions with copays greater than $10. (Table 2).

First-fill rates differed by therapeutic class and route of administration. While no differences were observed in rates between biguanides and sulfonylureas, prescriptions for biguanides or sulfonylureas were more likely to be filled (87%) than prescriptions for all other antidiabetic agents (74%, p < 0.0001). Additionally, the first-fill rate for injectable insulin was 74%, significantly less than the rate for oral agents (86%, p = 0.030).

The following factors had no relationship to first-fill rate: age, sex, race, morbidity score, number of office visits, prescribing a drug during an office visit, and total number of medications ordered ten days either before or after the index medication order.

Impact of First-Fill Adherence on A1c values

Five hundred and sixty-five patients had A1c values both at baseline and follow-up (Table 3). At baseline, the mean A1c levels for patients that were above goal was statistically different for patients who eventually filled their prescriptions (mean = 8.3%, SD = 1.9) compared to those patients who did not fill their prescription (mean = 7.7%, SD = 1.5, p = 0.004). After the index medication order date, absolute reductions in A1c values for patients who filled their prescription were 3.25 times that of non-filling patients (1.3% reduction in the fill group vs. 0.4% in the no-fill group, p < 0.0001).

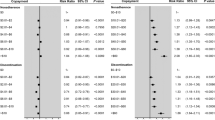

Predictors of First Fills from a Logistic Regression Model

All statistically significant and clinically meaningful individual predictors (i.e. found in Table 1) were considered in a logistic regression model to determine the best predictors of first-fills (Table 2). Compared to biguanides, patients prescribed multiple medications or other oral antihyperglycemic medication (excluding sulfonylureas) were significantly less likely to fill their naïve prescription (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.23, 0.86). A1c levels ≥ 9% (OR 2.63, 95% CI 1.35, 5.09) and copays ≤ $10 (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.57–3.14) were associated with higher fill rates.

DISCUSSION

Among patients prescribed a new medication for diabetes, we found a first-fill rate of 85%. In multivariable analysis, three variables were significantly associated with filling such a prescription: baseline A1c, copay, and choice of initial medication.

Patients with initially higher A1c (≥ 9%) were more likely to fill their prescription than patients with lower A1c (<9%, OR 2.63, p < 0.001). This difference may reflect the relative intensity of physician counseling, a patient’s perception of his/her disease, other physician- or clinic-specific factors, and/or other selection biases or confounding by indication. The differences may have clinical implications. Intensifying physician counseling or closer monitoring of adherence may be important when treating patients with lower A1c values. Physicians may also consider adherence when selecting the therapeutic class with which they choose to treat newly diagnosed patients.

Consistent with the literature,7,8 we found that fill rates are linked to lower A1c levels on follow-up. A1c levels decreased over three times as much for patients who filled their prescription (−1.3%) relative to those who did not (−0.4%). The slight decrease for non-fillers may reflect improvements in diet and exercise regimens or regression to the mean.9

Of particular interest is copay. While the observed difference in median copays between fillers and non-fillers was small ($0.46, data not shown), it has been previously noted that copay increases of less than $2 can significantly reduce adherence rates.10 Larger copay amounts may be especially dangerous for asymptomatic patients who may elect to forgo needed medications.11 For this analysis, we initially categorized copay into several categories. However, the categories with copay >$10 were collapsed into one group because the estimated odds ratios were similar, and the cut-point of $10 was selected as this was the median copay amount among adherent patients. While it has been established that rising copays may worsen disparities and adversely affect health,12 more research is needed to examine the effect of copay on first-fill prescription orders.

Several factors that were previously found to relate to prescription fills4,13,14 were not so associated in our study, including age, sex, morbidity score, number of office visits, prescribing a drug during an office visit, and total number of medications ordered ten days either before or after the index medication order. This suggests that the interplay of numerous factors is responsible for prescription filling behavior, and a more nuanced understanding of patient motivations is required when trying to predict patient adherence.

The pairing of electronic medical record data with claims data allowed us to incorporate patient and prescription characteristics not available in adherence studies limited to claims data. However, because the study was limited to electronic data, no direct contact was made with patients to determine their perception of the severity of their disease or the effectiveness of their prescribed treatment. In addition, without patient follow-up, we may have underestimated prescription fills. A subset of patients may have been incorrectly categorized as non-adherent if they filled their prescription using a pharmacy benefit plan other than GHP or paid out of pocket. We attempted to diminish the possibility of this error by excluding patients from analysis who did not fill at least one other prescription through GHP prior to the index prescription. Another potential limitation of the analysis was the limited racial diversity of the population (95% Caucasian). The population was, however, diverse in other ways, including SES, age, and comorbid status.

Much attention has recently been paid to therapy intensification15,16 as a reason for patients with chronic disease not achieving target risk factor control. While provider factors are certainly an important target for improving outcomes for patients with chronic disease, this study highlights the equally important and often underestimated role of patient factors. An estimated 21 million individuals in the United States have diabetes with 1.5 million adults newly diagnosed every year.17 If our results are generalizable, an 85% fill rate corresponds to over 200,000 diabetic patients not filling their initial prescription for an antihyperglycemic medication, and potentially being exposed to costly second-line agents or drugs with more adverse effects. A recent meta-analysis of 23 studies that measured antihyperglycemic medication adherence and only included patients who had already filled an initial prescription (i.e. second-fill and ‘persistence’) found an overall adherence rate of 68%.13 If an 85% first-fill rate from the current study is factored in, the net actual repeat-fill rate would be substantially lower at 58% (i.e. 85% x 68%). This estimate is much lower than current belief on prescription fills, and suggests that substantial gains in chronic disease care may be achieved through increased attention to issues related to filling prescriptions.

Our findings suggest that future research should focus on identifying the different stages of the prescription cycle (for example, first obtaining the medication, using the medication, refilling the medication from the pharmacy, or obtaining another order from the physician) and quantifying adherence at each step, which is now possible in many settings as more records are electronic.

As EHRs become more prevalent, health services research initiatives must harness the wealth of information provided by this resource. By using established electronic databases, including EHR and pharmacy claims data, and carefully excluding patients who had not used their pharmacy benefits in the past, this study avoided biases associated with patient self-report and was able to assess prescription first-fill rates. Increased awareness of prescription non-fill rates and identification of factors that influence non-fill can help physicians proactively optimize therapy by maximizing patient acceptance, adherence, and outcomes.

Abbreviations

- HER:

-

Electronic Health Records

- GHP:

-

Geisinger Health Plan

- A1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

References

Haynes TB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Compliance in Health Care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979.

Balkrishnan R. The importance of medication adherence in improving chronic-disease related outcomes: what we know and what we need to further know. Med Care. 2005;43(6):517–20.

Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Medication costs, adherence, and health outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(4)220–9.

McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2868–79.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5)373–83.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology, 2nd edn. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

Pladevall M, Williams LK, Potts LA, Divine G, Xi H, Lafata JE. Clinical outcomes and adherence to medications measured by claims data in patients with diabetes. Diab Care. 2004;27(12):2800–5.

Schetman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diab Care. 2002;25(6):1015–21.

Kienle GS, Kiene H. The powerful placebo effect: Fact or fiction? J Clin Epi. 1997;50(12):1311–8.

Johnson RE, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Eldredge MB. The effect of increased prescription drug cost-sharing on medical care utilization and expenses of elderly health maintenance organization members. Med Care. 1997;35:1119–31.

Babazono A, Tsuda T, Yamamoto E, Mino Y, Une H, Hillman AL. Effects of an increase in patient copayments on medical service demands of the insured in Japan. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(3):465–75.

Chernew M, Gibson TB, Yu-Isenberg K, Sokol MC, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care. J Gen Int Med 2008;epub ahead of print.

DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004;42(3):200–9.

van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, van Dijk L, de Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. Patient adherence to medical treatment: A review of reviews. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;7(55).

Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Importance of therapy intensification and medication nonadherence for blood pressure control in patients with coronary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(3):271–6.

Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Karter AJ, et al. Why don’t diabetes patients achieve recommended risk factor targets? Poor adherence versus lack of treatment intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):588–94.

American Diabetes Association. Diabetes statistics. Available at http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-statistics.jsp. Accessed on May 7, 2008.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Dr. Shah receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as a Physician Faculty Scholar. None of the funders played any role in the design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Shah had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Nirav Shah has received unrestricted research grants from AstraZeneca, Berlex, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; he has served as a consultant for Cerner Lifesciences and LifeTech Research. None of the authors have any financial interests in any of the devices or companies mentioned in this report, except that Chris Zacker works for the sponsor of this study.

Nirav Shah, Annemarie Hirsch, Scott Taylor, Chris Zacker, and Walter Stewart all played significant roles in the data collection, analysis, and write-up of the manuscript. Nirav Shah, Scott Taylor, and Walter Stewart conceived of the idea and obtained funding. Nirav Shah is the guarantor of the manuscript. Design and conduct of the study: Nirav Shah, Scott Taylor, Annemarie Hirsh, Walter Stewart, Chris Zacker; Collection, management, analysis: Nirav Shah, Craig Wood, Annemarie Hirsch; Interpretation of the data: Nirav Shah, Annemarie Hirsch, Scott Taylor, Walter Stewart, Craig Wood, Chris Zacker; Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: Nirav Shah, Annemarie Hirsch, Scott Taylor, Walter Stewart, Craig Wood.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Annemarie G. Hirsch, Scott Taylor, and G. Craig Wood report no conflicts of interest. Nirav R. Shah has held a consultancy position for Cerner LifeSciences within the past 3 years and has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, AstraZeneca, and Merck. Christopher Zacker has been employed with Novartis. Walter F. Stewart has received grants within the past 3 years from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, AstraZeneca, and Merck.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, N.R., Hirsch, A.G., Zacker, C. et al. Factors Associated with First-Fill Adherence Rates for Diabetic Medications: A Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 233–237 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0870-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0870-z