Abstract

Summary

We evaluated vertebral fracture prevalence using DXA-based vertebral fracture assessment and its influence on the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) tool-determined 10-year fracture probability in a cohort of oldest old nursing home residents. More than one third of the subjects had prevalent vertebral fracture and 50% osteoporosis. Probably in relation with the prevailing influence of age and medical history of fracture, adding these information into FRAX did not markedly modify fracture probability.

Introduction

Oldest old nursing home residents are at very high risk of fracture. The prevalence of vertebral fracture in this specific population and its influence on fracture probability using the FRAX tool are not known.

Methods

Using a mobile DXA osteodensitometer, we studied the prevalence of vertebral fracture, as assessed by vertebral fracture assessment program, of osteoporosis and of sarcopenia in 151 nursing home residents. Ten-year fracture probability was calculated using appropriately calibrated FRAX tool.

Results

Vertebral fractures were detected in 36% of oldest old nursing home residents (mean age, 85.9 ± 0.6 years). The prevalence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia was 52% and 22%, respectively. Ten-year fracture probability as assessed by FRAX tool was 27% and 15% for major fracture and hip fracture, respectively. Adding BMD or VFA values did not significantly modify it.

Conclusion

In oldest old nursing home residents, osteoporosis and vertebral fracture were frequently detected. Ten-year fracture probability appeared to be mainly determined by age and clinical risk factors obtained by medical history, rather than by BMD or vertebral fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nursing home residents are at very high risk of osteoporotic fractures since fracture rate in this population is between 3 and 11 times higher than in age- and gender-matched community dwellers [1–5]. For instance, nearly 40% of hip fractures occur in nursing home residents [6, 7]. Nursing home residents with a history of hip fracture or any prior osteoporotic fracture have an increased risk of another fracture already over the ensuing 2 years when compared to residents with no fracture history [8–10]. In addition to low BMD and prevalent fractures as predictor of hip fractures in white female residents [2, 10, 11], cognitive impairments and urinary incontinence [12, 13] are risk factors for falls, contributing to increase risk of fracture. A high prevalence of sarcopenia is found in patients with a recent hip fracture, underlining the link between low muscle mass and fragility fracture in frail elderly [14, 15].

The prevalence of vertebral fracture in nursing home residents is not known. Whether the detection of such fracture and their inclusion into the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) algorithm could improve fracture probability evaluation in this specific population, and thereby further identify patients at increased risk of fracture deserving therapy, is not established. This is of particular interest since in several countries, age-adjusted hip fracture secular trend appears to be reversing [16, 17], and that this reversal seems to be related to a decrease in hip fracture incidence specifically in nursing homes [18].

In this study, we addressed the following questions: (1) Is vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) as measured by DXA using a nursing home visiting truck applicable in oldest old nursing home residents? (2) What is the vertebral fracture prevalence in a population of nursing home residents at high risk of fracture? (3) Would the detection of vertebral fracture or introducing BMD values modify fracture probability, based on clinical risk factors, as estimated by the FRAX tool?, and (4) What is the sarcopenia prevalence in this population? The results indicate that in oldest old nursing home residents, osteoporosis and vertebral fracture are frequent and that the 10-year fracture risk is barely influenced by introducing BMD or VFA values in the FRAX tool.

Patients and methods

Patients were recruited among five nursing homes of the Geneva area which comprises 50 homes for 3,500 residents. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the Geneva Medical Doctors Association. Inclusion criteria consisted of the ability to sign an informed consent, a life expectancy estimated as greater than 1 year, and the ability to walk with or without a walking aid. Exclusion criteria were: subject refusal (15% of 879 residents in the five nursing homes), walking impairment and incapacity to climb the four stairs to get into the densitometry truck (15%), cognitive impairment (45%), an osteodensitometry examination performed less than 1 year previously (5%), active cancer disease with or without bone metastasis (10%), and other causes (10%). Cognitive impairment was defined as the incapacity to provide an informed consent, based on the evaluation of understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and verbal expression [19].

Clinical data

Three questionnaires were administered. The first one concerned osteoporotic risk factors, history of falls, current medication, and comorbidities. The second one evaluated the activities of daily living according to Katz [20] and a nursing care load score [21]. The third one estimated dietary calcium and protein intakes [22]. Based on clinical risk factors, we calculated the FRAX score calibrated for Swiss life expectancy and fracture incidence [23, 24] to estimate the 10-year probability of fracture. Fracture occurrence was based on medical history and/or results from vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) [25].

BMD at the level of lumbar spine, hip and femoral neck, whole-body BMC, lean and fat masses were measured by DXA using a Hologic QDR 4,500 in a mobile truck. Vertebral body deformity was evaluated using the VFA method, with the subject in supine position [25]. Vertebral fractures were detected using the Genant semiquantitative method [26]. Grade 1 vertebral fracture was defined as a 20–25% in anterior, middle, or posterior heights, grade 2 as a 25–40%, and grade 3 as a reduction superior to 40%. The degree of sarcopenia was estimated from appendicular lean mass (ALM) per height square, with cutoff values of 7.26 and 5.45 kg/m2, as assessed by DXA, in men and women, respectively, for class II severe sarcopenia (ALM/ht2 ratio below −2 standard deviation (SD) of the gender-specific mean value of young controls), and 8.51 and 6.44 kg/m2 for class I moderate sarcopenia (ALM/ht2 ratio between −1 and −2 SD) [27, 28].

Statistical analysis

The results are shown as means±SEM.

Results

Patient characteristics

The five nursing homes out of the 50 in the Geneva area housed 879 residents (25%). Among them, 151 (17%) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Four out of five were women. Mean age was 85.9 years (range, 64 to 98 years; Table 1). Their reported dietary intakes of calcium and protein were suboptimal. With a mean BMI of 26.4 kg/m2, the nutritional status appeared to be satisfactory (Table 2). The impaired activity of daily living was exemplified by altered Katz and care load scores. Half of them described a fall during the previous year, and slightly less reported a history of fracture. Very few were receiving an osteoporosis therapy (6% bisphosphonates and 21% some calcium and/or vitamin D).

DXA measurements

More than 50% of the subjects had a T-Score value at the spine or the hip below −2.5 SD (Table 2). Using the criteria of 7.26 and 5.45 kg/m2 for appendicular lean mass for men and women, respectively, 56% of the men and 13% of the women were considered as class II sarcopenic, and 31% and 44% as class I sarcopenic (≤8.51 and 6.44 kg/m2, respectively). In both genders, 64% were at least class I sarcopenic (87% for men and 57% for women).

Vertebral fracture assessment

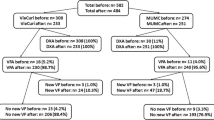

In this population of elderly nursing home residents, 36% had a vertebral fracture as evaluated by VFA (Table 3). When only grade 2 or 3 vertebral fracture was considered [26], 28% had a fracture; the mean number of all fractures per subjects was 1.5. Men and women were similarly affected. The majority of the fracture was detected at T12 and L1 levels (Table 4). Note that particularly at T4 to T6, not all vertebral body could be visualized and analyzed. When FRAX tool calculation of 10-year fracture probability was applied to this population, the values obtained amounted to 27% and 15% for major fractures and for hip fracture, respectively (Table 5). In the subjects with prevalent fracture, these values were 35% and 18% for men and women, respectively, and 21% and 11% in those without prevalent fracture. Adding BMD and/or DXA-based VFA results did not markedly modify this probability. This was true for major osteoporotic fracture and for hip fracture specifically.

Discussion

In this prospective cross-sectional study conducted in oldest old nursing home residents, we detected vertebral fractures in 36% of them, osteoporosis in 52%, and sarcopenia in 22%. Adding BMD or vertebral fracture assessment values to the FRAX algorithm did not significantly modify the 10-year fracture probability.

To our knowledge, this is the first survey conducted in long-term care residents, looking at the prevalence of vertebral fracture in this population using DXA-based vertebral fracture assessment. The aims were two. First, we wanted to evaluate the feasibility of this technique in such a population of oldest olds with a likely high prevalence of osteoporosis and poor definition of vertebral body edge, hence whether DXA-based VFA could be applied. With the constraints of the software and hardware used, we found that a substantial number of examinations precluded vertebral body edges to be precisely determined, particularly in the T4–T6 region. Under these conditions, the number of fractures detected may be slightly underestimated. However, 36% of the patients, with a similar distribution in women and men, displayed a vertebral fracture. This number went down to 28%, when only grade 2 and 3, according to Genant classification, were considered. Second, we addressed the issue whether a systematic detection of vertebral fracture and/or osteoporosis would modify the 10-year fracture probability as assessed by the FRAX tool, calibrated for regional values of life expectancy and fracture incidence [24]. The results indicate that it was not the case since the 32% probability for major fracture and 17% for hip fracture in women and the 12% and 7% in men remain similar by adding VFA results. Similarly, BMD values did not increase FRAX-determined fracture probability. This could indicate that most of the fracture risk was captured by age and the medical history of prevalent fracture, which was as high as 44% (50% in women and 22% in men). This number is higher than that one found in long-term care residents in Edmonton (Canada) (34%) [29]. In this report, the patients were slightly younger (84 ± 8 versus 86 ± 6 years (x±SD) than in our study. In elderly Brazilian subjects living in the community, prevalence of radiographically ascertained vertebral fractures was as high as 50% and 31.8% in women and men aged 80 years and older, respectively [30]. In contrast, prevalent vertebral fractures were 33.9% and 27.8% in Caucasian women in the USA and Europe, respectively [31, 32].

Under these conditions, a systematic screening for vertebral fracture and/or osteoporosis does not appear to identify more patients at increased risk, deserving thereby a therapy [33]. These results would not support an extensive screening with DXA in this population.

DXA-based osteoporosis diagnosis at the spine or the hip was found in 52% of the patients (58% in women and 31% in men). This figure is lower than previously reported results, which amounted to 54% to 80%, but sometimes with a diagnosis established clinically [2, 11, 29, 34–36]. Falls are particularly frequent in oldest old living in institution [37]. Over the previous 12-month period, 54% reported at least one fall in our study. This is higher than 31–34% in Canadian long-term care facilities [29, 36]. For comparison, in a population of community-dwelling women aged 76–86 years, prevalence of osteoporosis at the spine or hip was 18.4% (27.6% had BMD values below −2.0 T-Score) [38].

Despite a 44% history of fracture, a small proportion of patients were on bisphosphonate treatment (6%). However, implementation of effective fracture prevention efforts should be a priority at the time of admission to nursing homes since fracture incidence is the highest during the first months after admission [39]. In various surveys, the prevalence of effective osteoporosis treatment amounted from 9% to 38% [29, 36, 40–42]. This confirms the marked undertreatment of osteoporosis in this high-risk population [43–46]. In contrast, 21% received some calcium and vitamin D, thus a prevalence similar to 27% in Giangregorio’s study [36]. Some of the differences obtained in our study as compared with others rely on the patient recruitment versus an unselected survey. Indeed, to be enrolled, our patients had to fulfill inclusion criteria, including an acceptable capacity of judgment, a mobility sufficient to get into the truck, and the signature of an informed consent. Thus, only 17% of the nursing home residents fitted these requirements. Nutritional status was better than previously reported in this kind of setting as suggested by BMI values, an only 22% prevalence of sarcopenia as compared to 33% among nursing home older Italian residents [47], and calcium and protein intakes close to 900 mg/day and 0.9 g/kg BW per day, respectively. Whether the constant efforts devoted to improve nutrition in long-term care of oldest olds are contributing to the reversal of secular trend of hip fracture, as evidenced in the same region, deserve further study [16, 17, 48]. At least the reversal of the trend was observed before the introduction of bisphosphonates, at a time when the interest for calcium, vitamin D, and nutrition spread out in the elderly population.

In conclusion, this survey conducted in oldest old nursing home residents underline the high prevalence of fracture history, of prevalent vertebral fracture, and of osteoporosis. However, the number of patients treated remains extremely low. A systematic assessment of bone mineral density and/or vertebral fracture does not appear to modify the 10-year fracture probability obtained by the FRAX tool based on age and medical history in this specific elderly population.

References

Rudman IW, Rudman D (1989) High rate of fractures for men in nursing homes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 68:2–5

Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ, Buie VC et al (1999) The prevalence of osteoporosis in nursing home residents. Osteoporos Int 9:151–157

Brennan Saunders J, Johansen A, Butler J et al (2003) Place of residence and risk of fracture in older people: a population-based study of over 65-year-olds in Cardiff. Osteoporos Int 14:515–519

Butler M, Norton R, Lee-Joe T et al (1996) The risks of hip fracture in older people from private homes and institutions. Age Ageing 25:381–385

Sugarman JR, Connell FA, Hansen A et al (2002) Hip fracture incidence in nursing home residents and community-dwelling older people, Washington State, 1993–1995. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1638–1643

Schurch MA, Rizzoli R, Mermillod B et al (1996) A prospective study on socioeconomic aspects of fracture of the proximal femur. J Bone Miner Res 11:1935–1942

Nydegger V, Rizzoli R, Rapin CH et al (1991) Epidemiology of fractures of the proximal femur in Geneva: incidence, clinical and social aspects. Osteoporos Int 2:42–47

Lyles KW, Schenck AP, Colon-Emeric CS (2008) Hip and other osteoporotic fractures increase the risk of subsequent fractures in nursing home residents. Osteoporos Int 19:1225–1233

Berry SD, Samelson EJ, Ngo L et al (2008) Subsequent fracture in nursing home residents with a hip fracture: a competing risks approach. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1887–1892

Nakamura K, Takahashi S, Oyama M et al (2010) Prior nonhip limb fracture predicts subsequent hip fracture in institutionalized elderly people. Osteoporos Int 21:1411–1416

Chandler JM, Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ et al (2000) Low bone mineral density and risk of fracture in white female nursing home residents. JAMA 284:972–977

Colon-Emeric CS, Biggs DP, Schenck AP et al (2003) Risk factors for hip fracture in skilled nursing facilities: who should be evaluated? Osteoporos Int 14:484–489

Girman CJ, Chandler JM, Zimmerman SI et al (2002) Prediction of fracture in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1341–1347

Fiatarone Singh MA, Singh NA, Hansen RD et al (2009) Methodology and baseline characteristics for the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study: a 5-year prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64:568–574

Lloyd BD, Williamson DA, Singh NA et al (2009) Recurrent and injurious falls in the year following hip fracture: a prospective study of incidence and risk factors from the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64:599–609

Chevalley T, Guilley E, Herrmann FR et al (2007) Incidence of hip fracture over a 10-year period (1991–2000): reversal of a secular trend. Bone 40:1284–1289

Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR et al (2011) Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 22:1277–1288

Guilley E, Chevalley T, Herrmann F et al (2008) Reversal of the hip fracture secular trend is related to a decrease in the incidence in institution-dwelling elderly women. Osteoporos Int 19:1741–1747

Appelbaum PS (2007) Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 357:1834–1840

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al (1963) Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185:914–919

D’Hoore W, Guisset AL, Tilquin C (1997) Increased nursing-time requirements due to pressure sores in long-term-care residents in Quebec. Clin Perform Qual Health Care 5:189–194

Morin P, Herrmann F, Ammann P et al (2005) A rapid self-administered food frequency questionnaire for the evaluation of dietary protein intake. Clin Nutr 24:768–774

Kanis JA, Burlet N, Cooper C et al (2008) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 19:399–428

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Kanis JA et al (2009) Remaining lifetime and absolute 10-year probabilities of osteoporotic fracture in Swiss men and women. Osteoporos Int 20:1131–1140

Lewiecki EM, Laster AJ (2006) Clinical review: clinical applications of vertebral fracture assessment by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4215–4222

Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C et al (1993) Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8:1137–1148

Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D et al (1998) Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 147:755–763

Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R (2002) Low relative skeletal muscle mass (sarcopenia) in older persons is associated with functional impairment and physical disability. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:889–896

Beaupre LA, Majumdar SR, Dieleman S et al (2012) Diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis before and after admission to long-term care institutions. Osteoporos Int 23:573–580

Lopes JB, Danilevicius CF, Takayama L et al (2011) Prevalence and risk factors of radiographic vertebral fracture in Brazilian community-dwelling elderly. Osteoporos Int 22:711–719

Black DM, Palermo L, Nevitt MC et al (1995) Comparison of methods for defining prevalent vertebral deformities: the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 10:890–902

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J et al (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in european men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11:1010–1018

Rizzoli R, Bruyere O, Cannata-Andia JB et al (2009) Management of osteoporosis in the elderly. Curr Med Res Opin 25:2373–2387

Sallin U, Mellstrom D, Eggertsen R (2005) Osteoporosis in a nursing home, determined by the DEXA technique. Med Sci Monit 11:CR67–CR70

Elliott ME, Binkley NC, Carnes M et al (2003) Fracture risks for women in long-term care: high prevalence of calcaneal osteoporosis and hypovitaminosis D. Pharmacotherapy 23:702–710

Giangregorio LM, Jantzi M, Papaioannou A et al (2009) Osteoporosis management among residents living in long-term care. Osteoporos Int 20:1471–1478

Becker C, Rapp K (2010) Fall prevention in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med 26:693–704

Frisoli A Jr, Chaves PH, Ingham SJ et al (2011) Severe osteopenia and osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and frailty status in community-dwelling older women: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) II. Bone 48:952–957

Rapp K, Lamb SE, Klenk J et al (2009) Fractures after nursing home admission: incidence and potential consequences. Osteoporos Int 20:1775–1783

Colon-Emeric C, Lyles KW, Levine DA et al (2007) Prevalence and predictors of osteoporosis treatment in nursing home residents with known osteoporosis or recent fracture. Osteoporos Int 18:553–559

Jachna CM, Shireman TI, Whittle J et al (2005) Differing patterns of antiresorptive pharmacotherapy in nursing facility residents and community dwellers. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1275–1281

Parikh S, Avorn J, Solomon DH (2009) Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in nursing home populations: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:327–334

Rojas-Fernandez CH, Lapane KL, MacKnight C et al (2002) Undertreatment of osteoporosis in residents of nursing homes: population-based study with use of the Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology (SAGE) database. Endocr Pract 8:335–342

Gupta G, Aronow WS (2003) Underuse of procedures for diagnosing osteoporosis and of therapies for osteoporosis in older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 4:200–202

Kamel HK, Hussain MS, Tariq S et al (2000) Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Am J Med 109:326–328

Parikh S, Mogun H, Avorn J et al (2008) Osteoporosis medication use in nursing home patients with fractures in 1 US state. Arch Intern Med 168:1111–1115

Landi F, Liperoti R, Fusco D et al (2012) Prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia among nursing home older residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67:48–55

Guilley E, Herrmann F, Rapin CH et al (2011) Socioeconomic and living conditions are determinants of hip fracture incidence and age occurrence among community-dwelling elderly. Osteoporos Int 22:647–653

Lippuner K, Johansson H, Kanis JA et al (2010) FRAX assessment of osteoporotic fracture probability in Switzerland. Osteoporos Int 21:381–389

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the nurses and all the care givers in the nursing homes, to Ms. C. Genet for DXA evaluations, Ms. M-A. Schaad RN, and A. Sigaud RN for the information delivered in the nursing homes. We thank the AETAS Foundation and the Geneva University Hospitals for their support. Ms. K. Giroux provided expert secretarial assistance.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodondi, A., Chevalley, T. & Rizzoli, R. Prevalence of vertebral fracture in oldest old nursing home residents. Osteoporos Int 23, 2601–2606 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-1900-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-012-1900-6