Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

To determine if the classification of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIs) affected clinical and functional outcome and to assess the need for follow-up of 3a tears in secondary care

Methods

Prospective data collection in 255 patients who sustained OASIs during repair with follow-up in a specialist clinic after 6 months.

Results

One hundred and thirty-two patients (51.7 %) sustained 3a tears, 81 (31.7 %) 3b tears, 27 (10.6 %) 3c tears and 15 (5.8 %) had 4th degree tears. Twenty-three patients (9 %) reported symptoms at 6-month follow-up. Eight patients reported anal incontinence of liquid or solid stool. Among patients who sustained 3a tears, 8 patients were symptomatic: 7 had urgency and 1 had flatus incontinence. None of the patients who sustained 3a tears reported incontinence of solid/liquid stool. There appears to be no correlation with scan findings and symptoms at follow up. Most patients are asymptomatic. Urgency of faeces is the commonest symptom.

Conclusions

The vast majority of patients are asymptomatic. The necessity of seeing all these patients in secondary care for follow-up needs to be questioned. With effective primary care follow-up, there may be a place to follow up patients with 3a tears in the community during the routine 6-week postnatal check and refer the symptomatic patients to the hospital for further review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vaginal childbirth is associated with a high risk of perineal trauma with at least 85 % of women sustaining some form of perineal injury during vaginal delivery in the United Kingdom [1]. Obstetric trauma is the commonest cause of anal sphincter damage [2] and this is reported in 0.6–36 % of women as a consequence of vaginal delivery [3]. The range depends on the population studied and the method of identification used [4, 5]. Risk factors include birth weight over 4 kg (up to 2 %), persistent occipitoposterior position (up to 3 %), nulliparity (up to 4 %), induction of labour (up to 2 %), epidural analgesia (up to 2 %), second stage longer than 1 h (up to 4 %), shoulder dystocia (up to 4 %), midline episiotomy (up to 3 %) and forceps delivery (up to 7 %) [6].

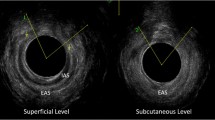

Obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIs) were formerly defined as third-degree perineal tears when there was partial or complete disruption of the anal sphincter muscles, involving the external (EAS) and sometimes the internal anal sphincter (IAS) muscles. A fourth-degree tear was defined as a disruption of the anal sphincter muscles with a breach of the rectal mucosa. Repair of third degree tears by end-to-end approximation was described initially in 1955 [7]; the procedure was widely adopted, but multiple retrospective studies have shown that approximately 23 to 33 % of women have or develop anal incontinence subsequently [8].

Kamm [9] reported on the early outcome of primary repair of the anal sphincter and showed that 65 % of 121 patients were asymptomatic with 61 % of them having ultrasound evidence of persistent anal sphincter defects. Problems with incontinence were associated with defects of the external anal sphincter in 37 % of patients.

Secondary overlap repair of the anal sphincter for faecal incontinence performed by colorectal surgeons years after the original obstetric insult appeared to produce good early results in 80 % of patients [10]. Sultan et al. [11] showed the feasibility and promising early results of primary overlap repair, but a subsequent small-randomised controlled trial did not find a difference in outcome with either technique [12]. Results from other trials are awaited. Structural sphincter damage is the main pathogenic mechanism causing the majority of anal incontinence after vaginal delivery [13].

A wide variation in the experience of repairing acute OASIs was found in a systematic review of the literature and a postal questionnaire survey of consultant obstetricians, trainee obstetricians and consultant coloproctologists [14]. This study recommended the need for a uniform, consistent and specific classification.

A classification of the severity of anal sphincter injury has been introduced and is used internationally: 3a/3b/3c/4 (Table 1) [15].

This classification has been welcomed as it describes more specifically the extent of injury and it has been recommended by the authors that all women with OASIs are followed up in secondary care. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends that all women who have had obstetric anal sphincter repair should be reviewed 6–12 weeks postpartum by a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist. If a woman is experiencing incontinence or pain at follow-up, referral to a specialist gynaecologist or colorectal surgeon for endoanal ultrasound and anorectal manometry should be considered [15]. The clinical relevance of this recommendation and the new classification has not been investigated.

We undertook an audit of 255 women who had a primary repair of OASIs from 2003 to 2006 in a tertiary referral centre in the United Kingdom. All women in our unit who sustain OASIs are followed up in a perineal clinic. The women are assessed by standard questionnaire and endoanal ultrasound scan as part of routine practice.

Materials and methods

This audit was registered with the clinical effectiveness team at the Southampton University Hospitals Trust. In this audit we aimed to see if the recent classification of OASIs affected clinical outcome. 255 women sustained obstetric sphincter trauma during childbirth at the Princess Anne Hospital between 2003 and 2006. Their details were collected from electronic patient data held in the hospital records with all demographic, medical and obstetric data along with description of the type of tear and surgical technical details. Trained Consultants and Registrars who had attended the OASIs repair-training workshop were deemed competent to independently perform all repairs.

All women who sustained a third/fourth degree tear underwent a primary repair in theatre according to the unit protocol. These patients had effective regional anaesthesia or general anaesthesia for the repair. Laxatives and antibiotics were prescribed in the immediate post-operative period for a week. All these women were offered a follow-up in the perineal clinic, 6 months after the repair with an endoanal scan. The patients also filled in a standardised symptom questionnaire.

Results

The total number of deliveries during the study period of 3 years was 14,930. The number of vaginal deliveries was 11,781 (79 %). Of these, 5,130 were primiparous and 6,651 were multiparous. There were 3,149 (21 %) caesarean sections in this study group. 3.3 % of primiparous women and 1.1 % of multiparous women who had a vaginal delivery sustained an injury to the anal sphincter complex identified at the time of delivery. This constitutes 2.1 % of all vaginal deliveries (n = 255) and 1.7 % of all deliveries.

Table 2 shows the severity of the tear and its relationship to parity.

Gestation

Of the 255 women who sustained OASIs, 240 (94.1 %) had term vaginal deliveries and 15 (5.9 %) had preterm deliveries at less than 37 weeks.

Birth weight

The range of birth weight was between 2.3 and 5.4 kg. See Table 3 for the distribution of severity by birth weight.

A simple Chi-squared test was used to assess the association between the categorical variables of birth weight and severity of tear. The p value was <0.0001, indicating a significant association. Increasing birth weight is more likely to be associated with the risk of sustaining an obstetric anal sphincter injury.

Mode of delivery

In the OASIs group, 72 % had a normal vaginal delivery, 13 % had a rotational forceps delivery, 4 % had non-rotational forceps delivery and 11 % had a ventouse delivery.

Tables 4 and 5 show the distribution of severity of the tear with parity and mode of vaginal delivery.

Length of the second stage

The duration of the second stage was 0–30 min in 71 patients, 30–60 min in 63 patients, 1–2 h in 71 patients and more than 2 h in 50 patients.

Table 6 shows the distribution of the severity of the tear with the length of the second stage.

A simple Chi-squared test was used to assess the association between the categorical variables of the length of the second stage and the severity of the tear. The p value was <0.0106, indicating a significant association. A significant statistical association was found with the severity of the OASIs and the increasing length of the second stage of labour.

Episiotomy

Seventy-nine patients (31 %) had an episiotomy performed prior to the tear and 174 (69 %) patients did not have an episiotomy.

Epidural analgesia prior to OASIs

Fifty-four (21 %) had epidural analgesia during labour.

Type of suture material used for sphincter repair

Of the 23 patients who reported symptoms, in 6 Vicryl had been used for the repair: 3 in the 3a and 3 in the 3b group. All others had PDS sutures for repair.

Method of repair

The type of repair was recorded in 243 patients. One hundred and twenty-six (49 %) had an end-to-end repair and 117 (45.8 %) had an overlap repair. No difference in symptoms or scan defects was found between these two techniques.

Antibiotics following the repair

Oral antibiotics were documented and prescribed in 216 patients (85 %).

Follow-up

One hundred and seventy-five patients (69 %) had attended the follow-up visit. Eighty (31 %) did not attend for follow-up. Of the 80 patients, 51 were primiparous and 29 were multiparous.

All 175 patients who attended the follow-up had an endoanal scan. One hundred and fifty-six of these patients attended the perineal clinic after the scan. This was done using the Starck scoring method.

The results of the endoanal scan in these patients are shown in Table 7:

The distribution of type of scan finding is shown in Table 8. Fifty-three patients had a positive scan finding. The defect was described as minimal defect(less than 1 h on the clock face) of EAS in 42, small defect (1 h on clock face)of EAS in 5 , full quadrant large defect of EAS in 3 and unquantified defect in 2 reports. There was 1 report of a small IAS defect.

Symptoms

Symptoms were assessed using Cleveland’s method for the presence and frequency of solid, liquid or flatus incontinence with documented use of pads and lifestyle restriction. Twenty-three (9 %) reported symptoms at 6 month follow-up. The correlation with symptom and scan finding is shown in Table 9. In the group that reported urgency, 3 had a defect less than an hour on the clock face (2–3a, 1–3b), 2 had a defect equivalent to an hour on the clock face (both 3b), 1 had a quadrant defect (fourth degree). Scan findings in the flatus incontinent group included a quadrant defect of EAS in a patient with a 3a tear. In the liquid incontinence group, 2 had defect less than an hour on the clock face (1–3b and 1–4) and 1 had a quadrant defect (fourth degree tear). In the solid incontinence group, 1 had an EAS defect of less than an hour on the clock face (3b tear).

Table 10 shows the distribution of the severity of the tear and the symptoms at follow-up.

There was no real correlation between scan findings and symptoms. Of 23 patients who had symptoms of incontinence, 11 showed a defect on the scan. However, 53 out of the whole group showed a defect on the scan. Forty-two of those with scan findings were asymptomatic.

The counts are really too small to be able to meaningfully assess whether particular symptoms are associated with specific tears. If assessed for the presence or absence of symptoms, the counts are virtually identical, indicating no association between symptoms and the severity of the tear (p > 0.999).

In the asymptomatic group, 42 had a scan finding, 34 less than a 1-h defect, 7 had a 1-h defect and 1 had a quadrant defect. The significance of a scan defect in an asymptomatic patient is unknown.

There was no trend or correlation with type/severity of tear, quantification of scan finding or type of symptom suffered.

The severity of the tear was similar in those who attended for follow-up and in those who did not. The distribution of the tear type among primiparas (n = 51) is not significantly different from that for the 181 primiparous patients followed up in Table 4, p = 0.7384. The distribution of the tear type among multiparas (n = 29) is not significantly different from that for the 74 multiparous patients who attended follow-up (p = 0.6388; Table 11).

Discussion

Third-degree tears constitute 2.1 % of all deliveries in this group. The incidence of OASIs is said to be increasing, although this is probably due to increasing vigilance and recognition of these tears [16, 17]. In a meta-analysis of studies where endoanal ultrasound was undertaken to study the incidence of anal sphincter injury after vaginal deliveries, approximately 1 in 4 primiparous and 1 in 3 multiparous women had evidence of an anal sphincter defect [18]. It is difficult to ascertain whether ultrasound identification correlates with a clinical problem. This was not noted in our group of patients.

Of those who sustained OASIs 70.5 % were primiparous and 29.5 % were multiparous. 3.3 % of primiparous women and 1.1 % of multiparous women who had a vaginal delivery sustained an injury to the anal sphincter complex that was identified at the time of delivery. This is comparable to other European studies.

Statistical review suggests that there is a significant relationship between birth weight and severity of tear. Our study found a significant association between the severity of the tear and increasing birth weight. It is very important to counsel the patients when considering risk factors for OASIs. A recent review of 451 articles assessing risk factors for OASIs found birth weight above 4 kg to be an independent risk factor for sustaining OASIs [19].

It is suggested that instrumental delivery predisposes to OASIs. In a large UK randomised trial, OASIs were significantly more common after forceps (17 %) than after ventouse (11 %) delivery [20].

End-to end repair and overlap repair were done in 49 % and 45.8 % respectively in this group. Primary overlap repair was devised to be a possibly better technique [8], but to date, no trials have shown that to be the case. Other trials are ongoing to address this issue. Also, it is not possible to perform an overlap technique with a 3a tear.

The length of the second stage correlated with the severity of the tear in this series. A statistically significant association was found between severity of OASIs and the increasing length of the second stage of labour. This also helps to stratify the risk of sustaining OASIs when counselling patients regarding OASIs.

There was no real correlation between scan findings and symptoms. Of 23 patients who had symptoms of incontinence, 11 showed a defect on the scan. However, of the whole group 53 showed a defect on the scan. Forty-two of those with scan findings were asymptomatic. The severity of the tear was an expected measure affecting the severity of the symptoms and outcome after repair. Correlating symptoms with type of tear or scan finding was difficult in this series.

The reason for conducting this audit was to determine the usefulness of the current practice and the need for secondary care follow-up in all these patients.

More than half the OASIs (51 %) were 3a tears. The majority of these women were asymptomatic. Only 8 of the 132 women with 3a tears were symptomatic and only 1 of those patients had flatus incontinence. If effective primary care follow-up is provided, there may be a place to follow up these patients in the community during the routine 6-week postnatal check and refer symptomatic patients to the hospital for further review. With the vast majority of tears being 3a, there may be an opportunity to follow-up these patients by health visitor checks, practice nurse checks, general practitioner visit or telephone follow-up of symptoms. This may reduce the need to follow up these patients in the perineal clinic and to streamline the resources for symptomatic patients at an earlier date. Symptomatic patients picked up by telephone or at a primary care visit may be referred to the perineal clinic sooner or by open access by providing appropriate advice. Appropriate information leaflets with contact numbers must be provided. A 6-week postnatal check with the GP or midwife with referral of symptomatic patients can be used to streamline resources.

Thirty-one percent of patients did not attend their follow-up visit. The majority of these women were migrants whose first language was not English. It is imperative to make information more appropriate to this group of patients. Appropriately translated leaflets and written information should be made available. No difference in the distribution of tears was found between those who attended for follow-up and those who did not.

Fifty-three out of 175 patients (30 %) were found to have a defect on the scan, of which 11 were symptomatic. Different studies report 33–92 % defects after primary repair of OASIs. Ten percent defects were reported after structured training of trainees by Andrews et al. [21]. This may be a welcome change because of the senior supervision in the management of OASIs noted in this series as well. Anal continence is also dependent on pelvic floor support provided especially by the puborectalis muscle, which augments the function of the anal sphincters in maintaining continence. This may, perhaps, be how people with known sphincter defects maintain anal continence. Anal continence is a multifactorial mechanism that is still not completely understood.

In conclusion, OASIs are increasingly better detected and appropriately managed. The necessity of offering all patients a follow-up appointment in secondary care needs to be explored. It may be feasible to streamline the secondary care resources to monitor tears 3b or beyond with clear referral access to symptomatic patients in the 3a group. Factors other than the severity of the tear and ultrasound findings also play a role in maintaining anal continence.

References

McClandish R, Bowler U, van Asten H et al (1998) A randomised controlled trial of care of the perineum during second stage of normal labour. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105:1262–1272

Rao SS (2004) Diagnosis and management of faecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol 99:1585–1604

Christianson LM, Bovbjerg VE, McDavitt EC, Hullfish KL (2003) Risk factors for perineal injury during delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189(1):255–260

Laine K, Gissler M, Pirhoen (2009) Changing incidence of anal sphincter tears in four Nordic countries through the last decades. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 146(1):71–75

Faltin DL, Boulvain M, Irion O, Bretones S, Stan C, Weil A (2000) Diagnosis of anal sphincter tears by postpartum endosonography to predict faecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 95:643–647

McLeod NL, Gilmour DT, Joseph KS, Farrell SA, Luther ER (2003) Trends in major risk factors for anal sphincter lacerations: a 10 year study. J Obstet Gynecol Can 25:586–593

Cunningham CB, Pilkington JW (1955) Complete perineotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 70:1225–1231

Fenner DE, Genberg B, Brahma P, Marek L, DeLancey JO (2003) Fecal and urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery with anal sphincter disruption in an obstetrics unit in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189(6):1543–1549

Kamm MA (1998) Faecal incontinence. BMJ 316:528–532

Haadem K, Ohrlander S, Lingman G, Dahlström JA (1989) Successful late repair of anal sphincter rupture caused by delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 68(6):567–569

Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL (1999) Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 106(4):318–323

Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C (2000) A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183(5):1220–1224

Hayes J, Shatari T, Toozs-Hobson P, Busby K, Pretlove S, Radley S, Keighley M (2007) Early results of immediate repair of obstetric third-degree tears. Colorectal Dis 9(4):332–336

Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB (2002) Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review & national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2:9

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2007) Management of third and fourth degree tears. Green top guideline no. 29. RCOG, London

Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD (2003) Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br J Surg 90:1333–1337

Groom KM, Paterson-Brown S (2002) Can we improve on the diagnosis of third degree tears? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 101:19–21

Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW (2006) Occult anal sphincter injuries: myth or reality? BJOG 113:195–200

Dudding TC, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA (2008) Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Ann Surg 247(2):224–237

Johanson RB, Heycock E, Carter J, Sultan AH, Walklate K, Jones PW (1999) Maternal and child health after assisted vaginal delivery: five-year follow up of a randomised controlled study comparing forceps and ventouse. BJOG 106:544–546

Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH (2009) Outcome of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)—role of structured management. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 20(8):973–978

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Institutional review board process: Prospective permission was obtained from the clinical effectiveness team at University of Southampton NHS Hospital Trust and agreed to perform the data collection through the clinical audit process

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramalingam, K., Monga, A.K. Outcomes and follow-up after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Int Urogynecol J 24, 1495–1500 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2051-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2051-9