Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Prospective studies up to 1 year after repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) report anal incontinence in 33% of women and up to 92% have a sonographic sphincter defect. The aim of this study is to determine the outcome of repair by doctors who have undergone structured training using a standardized protocol.

Methods

Doctors repaired OASIS after attending a training workshop. The external anal sphincter was repaired by the end-to-end technique when partially divided and the overlap method when completely divided. Endoanal ultrasound was performed prior to suturing and 7 weeks later. A validated bowel symptom questionnaire was completed prior to delivery, at 7 weeks postpartum, and at 1 year postpartum.

Results

Fifty-nine women sustained OASIS. At 7 weeks, six (10%) had a defect on ultrasound. There was no significant deterioration in symptoms of fecal urgency, incontinence, or quality of life at 1 year after delivery.

Conclusions

The 1-year outcome after repair of OASIS appears to be good when repaired by doctors after structured training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Anal incontinence in women is mainly due to childbirth. Previously, such symptoms were attributed largely to pudendal neuropathy [1]. Anal endosonography, however, has confirmed initial suspicions that these symptoms may result from obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) [2, 3]. Despite recognition and primary repair of acute OASIS, between 19% and 61% of women have symptoms of anal incontinence [4] and between 34% and 92% have persistent anal sphincter defects on ultrasound [4, 5] within 3 months of delivery. This is a potentially devastating complication of vaginal delivery that can be a hygienic, social, and psychological problem. Furthermore, anal incontinence is a vastly underreported problem mainly due to embarrassment; consequently, many women suffer this affliction in silence.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) have recently updated their guideline [6] and there is a recommended protocol for the management of OASIS [7, 8]. We aimed to determine the outcome for women following acute OASIS if this protocol was strictly adhered to.

Materials and methods

Women having their first vaginal delivery over a 12-month period between February 2003 and January 2004 at Mayday University Hospital were invited to participate in a prospective study [9].

All consenting women had a perineal and rectal examination by the research fellow immediately after delivery. All OASIS were diagnosed clinically and were confirmed by either the on-call specialist registrar or consultant. These tears were classified according to the RCOG classification (Table 1) [10].

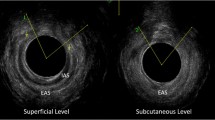

Endoanal ultrasound was performed in the left lateral position using a 10-MHz 360° rotating probe (B & K Naerum, Denmark) [3, 11]. All women had the endoanal ultrasound scans performed at delivery (prior to suturing) and repeated at 7 weeks postpartum in a dedicated perineal clinic. All real-time images along the length of the anal canal were video recorded (Fig. 1) and reviewed independently by two experts in endoanal ultrasonography (AHS and RT).

Women had their OASIS repaired according to a previously recommended protocol [7, 8], the salient points of which are presented in Table 2. All doctors performing repairs underwent structured education on a hands-on training course prior to repairing OASIS [12] (http://www.perineum.net).

Women completed a validated Manchester Health Questionnaire (relating to bowel function prior to delivery) within 48 h of giving birth [13]. This questionnaire was repeated at 7 weeks postpartum in the perineal clinic and again 1 year after delivery by a postal questionnaire. Women were sent the postal questionnaire at 1 year with a stamped addressed envelope and those who did not respond were sent a second mailing 4 weeks later.

The study was approved by the Croydon Ethics and Research Committee and all women gave written consent.

Statistics

Data was entered onto a Microsoft® excel database and analyzed with SPSS version 11.0. To investigate the change in ranks, the Friedman test was performed, and to compare proportions between independent groups, the Fisher's exact test was used.

Results

Fifty-nine women sustained OASIS over this time period. All 59 attended follow-up at a median of 7 weeks (range 5–12 weeks) and 43 (73%) completed a questionnaire 1 year later. Twenty-eight sustained grade 3a tears, 30 sustained grade 3b tears, and one a fourth-degree tear, and all these OASIS were confirmed by endoanal ultrasound prior to repair.

All 28 grade 3a tears were repaired using the end-to-end technique and all 30 grade 3b tears had an overlap repair (Fig. 2).

At follow-up, six women (10%), all of whom had sustained grade 3b tears had a defect on ultrasound (one combined external anal sphincter [EAS] and internal anal sphincter [IAS] defect and five EAS defects only); five of whom were followed up at 1 year. The one woman with a combined external and IAS defect on scan could actually represent a grade 3c tear which was incorrectly diagnosed as a grade 3b tear. There was no disagreement in scan diagnosis between the experts in anal endosonography. No women developed fecal incontinence over the 1-year period. There was no significant difference in symptoms of fecal urgency or flatus incontinence before, at 7 weeks after delivery, or at 1 year after delivery (Table 3). Two women had fecal urgency (one grade 3a tear and one grade 3b tear) and two women had flatus incontinence (one grade 3a tear and one grade 3b tear) at 1 year follow-up. There was no difference in quality of life 1 year after a primary repair when compared to that prior to sustaining OASIS (Table 4).

Discussion

Anal incontinence can have a devastating effect on a woman's social and psychological well-being. This is the first prospective study in which all women had accurate classification of OASIS confirmed clinically and by endoanal ultrasound prior to repair. We found that compared to before delivery, when a recommended protocol was adhered to by trained doctors, there was no significant change in symptoms of anal incontinence or fecal urgency at 1 year post delivery after a primary repair of an OASIS.

There have been at least 17 previous studies (Table 5) following up women after an OASIS to a maximum of 1 year. These studies have demonstrated anal incontinence between 7% [14] and 74% [15] of women with a mean of 33% following a primary repair. Of these 17 studies, a protocol for repair was available in ten units [14, 16–24]. We observed that the mean anal incontinence rate was 26% as opposed to 44% in those units where no protocol for repair was mentioned. It, therefore, remains to be established whether the outcome is significantly influenced by the presence of an approved protocol for repair of OASIS in the delivery suite.

Our protocol is based on the best available evidence base. Randomized trials have shown that laxative use is superior to a practice of bowel confinement [25] and that the use of lactulose alone is more beneficial when compared to a combination with a stool bulking agent [26]. Another randomized trial has confirmed that the use of antibiotics significantly reduced the rate of perineal wound infections [27]. There are no randomized trials regarding technique of repair of the torn anal epithelium (fourth-degree tear) and it would appear that either a continuous or interrupted suture technique is appropriate.

Three previous studies mention that doctors were trained prior to repairing OASIS [22–24]. However, only Williams et al. [23] described the details of the training given. In that study, all repairs were performed by trainees or consultants who had been trained on pig anal sphincters in workshops prior to performing repairs independently. In our study, all the doctors had undergone a structured training program in a hands-on training workshop [12] (http://www.perineum.net). This consisted of lectures, video demonstrations on OASIS repair, and hands-on training on cadaveric porcine anal sphincters and specially designed training models (Limbs & Things™). This structured workshop has previously been shown to change clinical practice and increase knowledge of the anatomy of the anal sphincter [12]. Following attendance on the course, all repairs were performed under direct supervision by doctors who were already trained until it was agreed that the trainee could repair OASIS independently.

Different techniques of repair of the EAS have been described [28]. The most frequently used technique in the UK appears to be the end-to-end repair with “figure of eight” sutures [29]. Colorectal surgeons, however, prefer the overlap technique for secondary anal sphincter repair for patients presenting with fecal incontinence. Based on this, Sultan et al. [29] initially described the overlap technique for primary EAS repair but also separate repair of the torn IAS. To date, there have been three randomized trials evaluating the overlapping and end-to-end technique for the repair of OASIS. The first of these studies by Fitzpatrick et al. [30] recruited 112 primiparous women. No significant differences between the two methods of repair were identified although there appeared to be a trend towards more symptoms in the end-to-end group. Compared to our study and the earlier description of Sultan et al. [29], there were methodological differences in that the torn IAS was not identified and repaired separately and they used a constipating agent for 3 days after the repair. It is also unclear as to how an overlap repair could have been performed in women who had partial tears of the EAS. More recently, Williams et al. [23] performed another randomized controlled trial on 112 primiparous and multiparous women. Only 54% were followed up at 1 year and it appears that <10% had symptoms of anal incontinence although precise details are not given in their paper. Williams et al. also performed overlap EAS repairs on women with both partial and complete OASIS. The original description of the overlap repair in OASIS by Sultan et al. [29] only describes the anal sphincter being overlapped after complete disruption of the EAS. In the randomized controlled trial by Fernando et al. [24], only women with complete disruption of the anal sphincter or women with >50% of the external sphincter was torn (3b tears) were included. In their study, they only repaired partial EAS tears by the overlap technique after completely dividing the residual fibers of the EAS. They found that, compared to women who had an end-to-end repair, none of those who had an overlap repair suffered anal incontinence (0 vs. 6/25 [24%], p = 0.009) or perineal pain (0 vs. 5/25 (20%) at 12 months. In our study, the overlap technique was only used when the EAS was completely torn), and grade 3a tears were repaired by the end-to-end technique using mattress sutures [7]. It is only possible to perform a true overlap repair if the two ends of muscle are completely divided. Therefore, if there were a few strands of incompletely divided muscle, we divided it before performing an overlap repair. Otherwise, an end-to-end repair was performed. The findings of our study and those of Fernando et al. [24] suggest that the overlap technique should only be used when the EAS is completely divided. The overlap technique should not be undertaken when the EAS is partially torn, as this will place undue tension on the repair. In these circumstances, if a genuine overlap repair is intended, the remaining fibers of the external sphincter need to be divided.

Despite primary repair of OASIS, between 34% [18] and 92% [5] of women in previous studies had a defect on endoanal ultrasound. In our study, only six out of 59 (10%) women had a persistent sonographic defect, suggesting that, when this protocol was adhered to by trained surgeons or under direct supervision, better anatomical results than that previously described can be achieved.

The strengths of our study was the rigorous training and supervision given to doctors in training when repairing OASIS and the formal follow-up of women in a dedicated postnatal one-stop perineal clinic with a validated bowel symptom questionnaire and endoanal ultrasound.

There are four main limitations of our study. Firstly, while all women attended follow-up at 7 weeks, only 73% were available for follow-up at 1 year and we were not able to evaluate the symptom profile of the remaining women. However, given the significant proportion of our population who reside in temporary accommodation in an urban area with a mobile population, our follow-up is still reasonable. Secondly, during the recruitment period of this study, we only had one woman who sustained an IAS injury. Thirdly, there was no control group to compare the outcome for women when managed by doctors who had not undergone intensive training in the management of OASIS. Fourthly, the duration of follow-up was only 1 year and, as continence may change with time, a longer-term follow-up is being planned.

Anal incontinence is an unexpected complication for women following a vaginal delivery. The outcome, both in terms of symptoms of anal incontinence and restoration of anatomy, has been reported as suboptimal in previous studies. Our study suggests that the outcome of primary repair of OASIS might be improved when an evidence-based protocol is used by trained doctors. Ideally, a randomized multicentre trial should be conducted to determine the best protocol for the management of OASIS including endoanal ultrasound but the ultrasonographer should be blinded to the type of tear, suturing technique, and symptoms. In the absence of a randomized trial of operator experience, however, this study highlights the importance of training, the usefulness of a protocol, and the implementation of the evidence-based practice.

References

Snooks SJ, Setchell M, Swash M, Henry MM (1984) Injury to innervations of pelvic floor sphincter musculature in childbirth. Lancet 8(2):546–550

Snooks SJ, Henry MM, Swash M (1985) Faecal incontinence due to external anal sphincter division in childbirth is associated with damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor musculature: a double pathology. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 92(8):824–828

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Thomas JM, Bartram CI (1993) Anal sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med 329:1905–1911

Sultan AH, Thakar R (2007) Third and fourth degree tears. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner D (eds) Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. Springer, London, pp 33–51

Fitzpatrick M, Cassidy M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C (2002) Experience with an obstetric perineal clinic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 100:199–203

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2007) Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears—management. RCOG guideline no. 29. RCOG Press, London

Thakar R, Sultan AH (2003) Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Obstet Gynaecol 5(2):72–78

Andrews V, Thakar R, Sultan AH (2003) Management of third and fourth degree tears. Rev Gynaecol Pract 3:188–195

Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW (2006) Occult anal sphincter injuries—myth or reality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 113(2):195–200

Sultan AH (1999) Obstetric perineal injury and anal incontinence. Clin Risk 5:193–196

Thakar R, Sultan AH (2004) Anal endosonography and its role in assessing the incontinent patient. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 28(1):157–173

Thakar R, Sultan AH, Fernando R, Monga A, Stanton SL (2001) Can workshops on obstetric anal sphincter rupture change practice? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 12(3):S5

Bugg GJ, Kiff ES, Hosker G (2001) A new condition-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire for the assessment of women with anal incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 108:1057–1067

Sander P, Bjarnesen J, Mouritsen L, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A (1999) Anal incontinence after obstetric third-/fourth-degree laceration. One-year follow-up after pelvic floor exercises. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 10:177–181

Goffeng AR, Andersch B, Andersson M, Berndtsson I, Hulten L, Oresland T (1998) Objective methods cannot predict anal incontinence after primary repair of extensive anal tears. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 77:439–443

Sorensen M, Tetzschner T, Rasmussen OO, Bjarnesen J, Christiansen J (1993) Sphincter rupture in childbirth. Br J Surg 80:392–394

Crawford LA, Quint EH, Pearl ML, DeLancey JOL (1993) Incontinence following rupture of the anal sphincter during delivery. Obstet Gynecol 82(4):527–531

Mackenzie N, Parry L, Tasker M, Gowland MR, Michie HR, Hobbiss JH (2003) Anal function following third degree tears. Colorectal Dis 6:92–96

Go PMNYH, Dunselman GAJ (1988) Anatomic and functional results of surgical repair after total perineal rupture at delivery. Surg Gynecol Obstet 166:121–124

Uustal Fornell EK, Berg G, Hallbook O, Matthiesen LS, Sjodahl R (1996) Clinical consequences of anal sphincter rupture during childbirth. J Am Coll Surg 183:553–558

Kammerer-Doak DN, Wesol AB, Rogers RG, Cominguez CE, Dorin MH (1999) A prospective cohort study of women after primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter laceration. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181(6):1317–1322

Haadem K, Ohrlander S, Lingham G (1988) Long-term ailments due to anal sphincter rupture caused by delivery—a hidden problem. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 27:27–32

Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA, Richmond DH (2006) How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 113:201–207

Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Kettle C, Radley S, Jones P, O'Brien PMS (2006) Repair techniques for obstetric anal sphincter injuries. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 107(6):1261–1268

Mahony R, Behan M, O'Herlihy C, O'Connell PR (2004) Randomized, clinical trial of bowel confinement vs laxative use after primary repair of a third-degree obstetric anal sphincter tear. Dis Colon Rectum 47:12–17

Eogan M, Daly L, Behan M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C (2007) Randomised clinical trial of a laxative alone versus a laxative and a bulking agent after primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter injury. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 114(6):736–740

Duggal N, Mercado C, Daniels K, Bujor A, Caughey AB, El-Sayed YY (2008) Antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postpartum perineal wound complications: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 111(6):1268–1273

Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB (2002) Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review and national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2:9

Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL (1999) Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 106:318–323

Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O'Connell R, O'Herlihy C (2000) A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1220–1224

Walsh CJ, Mooney CJ, Upton GJ, Motson RW (1996) Incidence of third-degree perineal tears in labour and outcome after primary repair. Br J Surg 83:218–221

Nielsen MB, Hauge C, Rasmussen OO, Pedersen JF, Christiansen (1992) Anal endosonographic findings in the follow-up of primarily sutured sphincteric ruptures. Br J Surg 79:104–106

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN, Bartram CI (1994) Third degree obstetric anal sphincter tears: risk factors and outcome of primary repair. BMJ 308:887–891

Zetterstrom J, Lopez A, Anzen B, Norman M, Holmstrom B, Mellgren A (1999) Anal sphincter tears at vaginal delivery: risk factors and clinical outcome of primary repair. Obstet Gynecol 94(1):21–28

Belmonte-Montes C, Hagerman G, Vega-Yepez PA, Hernandez-de-Anda E, Fonseca-Morales V (2001) Anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery in primiparous females. Dis Colon Rectum 44(9):1244–1248

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Mayday Childbirth Charity Fund for funding this study.

Disclosure of interest

AS and RT are the directors of the hands-on workshops in the management of third-degree and fourth-degree tears at Mayday University Hospital, and proceeds from these courses are utilized by the Mayday Childbirth Charitable Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrews, V., Thakar, R. & Sultan, A.H. Outcome of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)—role of structured management. Int Urogynecol J 20, 973–978 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0883-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0883-0