Abstract

Biofeedback (BF) has been widely used in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunctions, mainly by promoting patient learning about muscle contraction with no side effects. However, its effectiveness remains poorly understood with some studies suggesting that BF offers no advantage over the isolated pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). The main objective of this study was to systematically review available randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of BF in female pelvic floor dysfunction treatment. Trials were electronically searched and rated for quality by use of the PEDro scale (values of 0–10). Randomized controlled trials assessing the training of pelvic floor muscle (PFM) using BF in women with PFM dysfunction were selected. Outcomes were converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Trials were pooled with software used to prepare and update Cochrane reviews. Results are presented as weighted mean differences with 95 % confidence intervals (CI). Twenty-two trials with 1,469 patients that analyzed BF in the treatment of urinary, anorectal, and/or sexual dysfunctions were included. PFMT alone led to a superior but not significant difference in the function of PFM when compared to PFMT with BF, by using vaginal measurement in the short and intermediate term: 9.89 (95 % CI −5.05 to 24.83) and 15.03 (95 % CI −9.71 to 39.78), respectively. We found a few and nonhomogeneous studies addressing anorectal and sexual function, which do not provide the cure rate calculations. Limitations of this review are the low quality and heterogeneity of the studies, involving the usage of distinct protocols of interventions, and various and different outcome measures. The results of this systematic review suggest that PFMT with BF is not more effective than other conservative treatments for female PFM dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a general term that describes a wide variety of functional clinical problems, usually associated with abnormalities in the pelvic floor compartments. The anterior compartment has been implicated in sexual and urinary function, with urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction the most common related symptoms. The posterior compartment is related to colorectal function, and the most common symptom seen in dysfunction of this compartment is fecal incontinence [1].

Physical therapy works to prevent and treat pelvic floor disorders. Its aim is to reduce the impact of pelvic floor dysfunction by improving the function and strength of the pelvic floor muscles (PFMs) [2]. Biofeedback (BF) is one physical therapy adjunct that might be useful in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction. It is a technique in which information about a normal physiological process is presented to the patient via subconscious methods and/or via the therapist offering a visual, auditory, or tactile cue [3]. This method has been used to teach patients awareness of their muscle functioning in order to improve and motivate the patient’s efforts during training [4–6].

Arnold Kegel used to base his training protocol on instructing patients about the correct way to contract their PFMs by using vaginal palpation and clinical observation. In his work, he also used the vaginal squeeze pressure measurement as BF during PFM exercises [7]. Since that time, a variety of other BF instruments have been used during PFM training (PFMT). However, some studies have shown that there is no advantage in using PFMT with BF in this manner; as a result, the effectiveness of this adjunctive modality remains poorly understood.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to systematically review randomized controlled trials that evaluated the additional effects of PFMT with BF when compared with other conservative treatments that do not include BF in the treatment of female pelvic floor dysfunction at short, intermediate, and long-term follow-up evaluations. The outcomes of interest were symptoms, quality of life, and function of the PFMs.

Methods

Data sources and searches

A computerized electronic advanced search was performed to identify relevant studies using specific databases. The search was conducted on MEDLINE (1966 to March 2011), LILACS (1993 to March 2011), PubMed (1974 to March 2011), and PEDro (1985 to March 2011). Terms for BF and PFM dysfunction were included in the search by use of MeSH (Medical Subject Headings of the National Library of Medicine) and keywords related to the domains of randomized controlled trials; BF and PFM dysfunction were used for each database (Appendix). We included only the studies written in English. One reviewer screened the search results for potentially eligible studies, while the other two reviewers independently reviewed the screened articles for eligibility. A third independent reviewer resolved any disagreement concerning the inclusion of trials.

Study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were randomized controlled trials comparing PFMT with BF to placebo or no treatment, PFMT without BF, electrical stimulation, or another conservative treatment for women with PFM dysfunction. Trials were considered to have evaluated PFMT with BF when the treatment included the following features:

-

PFMT with BF was used alone, without involving other techniques, and at least one of the groups received the treatment

-

PFMT with BF was used for treatment of urinary incontinence, stress urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, fecal incontinence, anal incontinence, constipation, or sexual dysfunction

Trials were included when one of the following outcome measures were reported: symptoms, quality of life or strength, and/or PFM function.

For this review, BF was regarded as a form of intervention involving visual or auditory feedback from an activity using a tool (surface electromyography or manometry). Several questions were proposed:

-

What is the effect of treatment with PFMT with BF on the symptoms of women with PFM disorders?

-

What is the effect of treatment with PFMT with BF on PFM function in women with disorders of the PFM?

-

What is the effect of treatment with PFMT with BF on quality of life in women with PFM disorders?

-

Does PFMT with BF yield better results when compared with conservative treatments that do not include BF?

Data synthesis and analyses

The methodological quality of the trials was assessed using the PEDro scale (values of 0–10), with scores extracted from the PEDro database [8]. The assessment of the quality of trials in the PEDro database was performed by two independent raters, and disagreements were resolved by a third rater. Methodological quality was not an inclusion criterion. Mean scores, standard deviations, and sample sizes were extracted from the studies. When this information was not provided in the trial, the values were calculated or estimated by use of methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [9]. Means, standard deviations, and sample sizes were extracted for short-term (less than 3 months after randomization), intermediate-term (at least 3 months but less than 6 months after randomization), and long-term (12 months or more after randomization) follow-up evaluations. When more than one outcome measure was used to assess symptoms, quality of life, perceived effect, strength, and/or PFM function, the outcome measure described as the primary outcome measure for the trial was included in this review.

Results were pooled when trials were considered sufficiently homogeneous with respect to participant characteristics, interventions, and outcomes. I2 was calculated using RevMan 5.1 [10] to assess statistical heterogeneity. I2 describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). A value of greater than 50 % may be considered to be substantial heterogeneity [9]. When trials were statistically homogeneous (I2 ≤ 50 %), pooled effects (weighted mean differences) were calculated by use of a fixed effects model. When trials were statistically heterogeneous (I2 ≥ 50 %), estimates of pooled effects (weighted mean differences) were obtained by use of a random effects model [9].

Results

Study selection

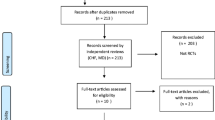

The first electronic database search resulted in a total of 404 articles after the removal of duplicates. As shown in Fig. 1, 67 articles were selected as potentially eligible on the basis of their title and abstract, and 45 were excluded from analysis [5, 11–54]. A total of 22 studies were included in this review. Of these, 15 studies addressed urinary dysfunction, 3 studies related to anorectal dysfunction, and 4 evaluated sexual dysfunction (Fig. 1). Among the studies that addressed urinary dysfunction, only five were included in the meta-analysis. Regarding studies that addressed anorectal and sexual dysfunction, no match was found; therefore, we could not include any of the studies in this meta-analysis.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality assessment by the PEDro scale revealed a median score of 5 (range 2–8) for studies evaluating BF in urinary dysfunction (Table 1). Random allocation was included in all trials. Concealed allocation was included in two trials [55, 56]. Comparability at baseline was not included in four trials [57–59]. Blind subjects and blinding of the therapist were not included in any of the trials. Blind assessors were included in four trials [55, 56, 60, 61]. Adequate follow-up was not included in four trials [62–65]. Intention-to-treat analyses were not included in three trials [60, 63, 66]. Between-group comparisons were not included in three trials [57, 63, 66]. Point estimates and variability were not included in one study [63].

With regard to studies that used BF to treat anorectal dysfunction, the PEDro scale revealed a median score of 5 (range 4–7) (Table 2). Random allocation, comparability at baseline, point estimates, variability, and between-group comparisons were included in all studies [70–72]. Concealed allocation was included in only one study [71], and blind assessors and adequate follow-up were included in two trials [70, 71]. Blind subjects, blinding of the therapist, and intention-to-treat analyses were not included in any of the trials.

With respect to studies which used BF to treat sexual dysfunction, the PEDro scale revealed a median score of 5 (range 4–7) (Table 3). In four trials that met the eligibility criterion, random allocation, between-group comparisons, and point estimates were included [73–76]. Concealed allocation and blind subjects were not included in any of these trials. Comparability at baseline was included in three trials [73–75]. Blinding of the therapist and blinding of the assessors were included in two trials [73, 75]. Adequate follow-up was included in one trial [76]. Intention-to-treat analysis was included in two trials [73, 76].

Study characteristics

BF in the treatment of urinary dysfunction

Fifteen randomized controlled trials included in this review evaluated BF in the treatment of urinary incontinence (Table 4). Fourteen studies evaluated the training of the PFMs with BF for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence and/or mixed urinary incontinence [55–60, 62–69]. One study evaluated PFM training with BF as treatment for overactive bladder [61].

PFMT with BF versus PFMT alone

Twelve trials with a total of 553 patients compared PFMT with BF and PFMT alone [55–58, 60, 61, 63, 65–69]. The methodological quality of these trials ranged from 2 to 8. For the five studies [56–58, 60, 65] in which the function of the PFM was evaluated by the vaginal pressure measurement, the results revealed no statistically significant differences between treatment groups [weighted mean difference on a scale of 0–100 = 9.89 points (–5.05 to 24.83)] (Fig. 2), as the assessment occurred very soon after the intervention. In the intermediate term, two studies [56, 58] were pooled. The results revealed no statistically significant differences between treatment groups with respect to PFM function [weighted mean difference on a scale of 0–100 = 15.03 points (−9.71 to 39.78)] (Fig. 3). Three studies were not included in the grouping of results because we were unable to extract their mean and standard deviation values [55, 63, 66], and four studies were not included because the studies did not use the same evaluation tools [61, 67–69]. No data were available for quality of life and urinary symptoms.

Forest plot of results from randomized controlled trials comparing PFMT with BF and PFMT alone in the treatment of urinary dysfunction. Evaluation of PFM function in the short term by the vaginal pressure measurement. Values represent effect sizes (weighted mean differences) and 95 % confidence intervals. The pooled effect sizes were calculated using a random effects model

Forest plot of results from randomized controlled trials comparing PFMT with BF and PFMT alone in the treatment of urinary dysfunction. Evaluation of PFM function in the intermediate term by the vaginal pressure measurement. Values represent effect sizes (weighted mean differences) and 95 % confidence intervals. The pooled effect sizes were calculated by using a random effects model

PFMT with BF versus control group

Two trials with a total of 109 patients compared PFMT with BF and no treatment [65, 67]. The methodological quality of these trials was 6 and 7, respectively. Those studies were not included in the pooled effects calculation because they did not use the same evaluation tools [65, 67].

PFMT with BF versus electrical stimulation

Three trials with a total of 117 patients that compared PFMT with BF and electrical stimulation were included [59–61]. The methodological quality of these trials ranged from 5 to 7. Those studies were not included in the pooled effects calculation because they did not use the same evaluation tools [59–61].

PFMT with BF versus another treatment

Three trials with a total of 463 patients were included. One study compared the efficacy of bladder training, pelvic floor exercises with BF, and combination therapy [62]. Another trial compared PFMT with BF and vaginal cone therapy [63]. The last study evaluated behavioral management for continence, an intervention to manage symptoms of urinary incontinence. The intervention involved self-monitoring, bladder training, and PFM exercises with BF [64]. The methodological quality of these trials ranged from 2 to 6. Two studies were not entered into the pooled effects calculation because the treatment protocols were different [62, 64], and for one study, it was not possible to extract the mean and standard deviation values [63].

BF in the treatment of anorectal dysfunction

Three randomized controlled trials included in this review evaluated BF for the treatment of fecal incontinence (Table 5). Of these, two compared PFMT with BF versus PFMT with BF and electrical stimulation [70, 71], and one compared PFMT with BF and electrical stimulation [72]. These studies treated a total of 133 patients. The methodological quality of these trials ranged from 4 to 7. These studies were not included in the pooled effects calculation because we were unable to extract the values for the means and standard deviations.

BF in the treatment of sexual dysfunction

Four randomized controlled trials were included in this review of BF as treatment for sexual dysfunction (Table 6). Among these studies, one compared vestibulectomy, PFMT with BF, and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis [73]. Two studies compared PFMT with BF and topical lidocaine gel for the treatment of vulvar vestibulitis [74, 76], and one was a follow-up study by Bergeron et al. 2001 [75]. These studies included a total of 173 patients. The methodological quality of these trials ranged from 4 to 7. Only one study included data concerning the mean and standard deviation [73, 75]. These studies were not included because the aim of this review was to combine data from many studies to obtain a pooled result.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we compared the effects of PFMT with BF versus other forms of treatment for patients with PFM dysfunction. Using the pooled effects calculations, we did not observe advantages with the use of BF in conjunction with PFMT over other conservative treatments.

In the studies related to the treatment of urinary dysfunction, PFMT with BF was compared to PFMT alone. The results favored the use of PFMT alone in the PFM function evaluation; however, the difference was not significant in either the short or intermediate term. Four of these studies [57, 58, 60, 65] showed that both PFMT with BF and PFMT alone were effective for treating urinary incontinence. However, Pages et al. [58] and Aksac et al. [65] reported that PFMT with BF resulted in improved PFM function, as evidenced by a higher contraction pressure and strength of the PFM. In other studies, the addition of BF to PFMT showed no significant effects; however, the authors reported that the use of an apparatus during training may motivate many women and that it should be an option in clinical practice [56]. Increased awareness is thought to motivate patients to perform exercises that restore function and health [77]. In four studies, patients had received information regarding the anatomy of the PFM, the function of the exercises to strengthen this musculature, and the relation of such exercises to urinary continence [56–58, 60]. One study reported regular measurement of muscle strength by a skilled physical therapist to achieve this effect [56]. In another study, the PFMT group performed the exercises using the digital palpation technique, while the patients were instructed to perform the proper contraction. They were instructed “to stop the micturition” [65]. Another factor that may have affected the results was the low number of participants in the studies included in the analysis. When the studies of PFM effects in the short term were combined, the PFMT with BF group had 101 patients, and the PFMT alone group had a total of 114 patients from the five studies included. In the analysis of intermediate-term effects, only two studies were included in the analysis, yielding a total of 61 patients in the PFMT with BF group and 73 in the PFMT alone group.

In the quality of life evaluation, it was not possible to pool an effect size for the meta-analysis. Several types of instruments were used to evaluate the quality of life. Among the studies that could be brought together in the meta-analysis, two studies evaluated quality of life using the King’s Health Questionnaire; however, the statistical analysis and the results were presented in different ways. One study [60] presented the total score of the questionnaire, whereas another study [61] presented results comparing the domains separately. Schmidt et al. [60] did not find a significant difference between groups on overall scores, but a significant reduction in subjective perception of the impact of the incontinence during the treatment period was observed. Wang et al. [61] had already reported the absence of a statistically significant impact on incontinence; however, the scores for overall quality of life were significantly greater after PFMT with BF. Therefore, PFMT with BF resulted in a better quality of life than PFMT alone after treatment.

A similar problem was observed regarding symptom evaluation. A bladder diary [55, 58, 60, 63], 7-day bladder diary [61], urodynamic analyses [57, 60, 61, 67], 1-h pad test [61, 65], 24-h pad test [57, 68], urine loss rate [56, 68, 69], 48-h pad test [56], 24-h bladder diary [67], incontinence frequency [65], and 30-min pad test [57] were used to evaluate the outcomes of PFMT with BF and PFMT alone. Although some studies used the same assessment tool, the protocols were different. Besides, there is a lack of information on how the evaluation was performed. For example, among studies that used the bladder diary only two describe the use of a 7-day and 24-h bladder diary [61, 67]. In studies where the 1-hour pad test was used, only one of them presents the results [65]. In urodynamic analyses, one study does not present the results [61], and in others, the method of performing the test differs among the studies [57, 60, 67]. As a result, it is impossible to gather the studies to perform the meta-analysis.

None of the studies in which PFMT with BF was compared with a control group was included in the pooled effects calculation [65, 67]. A variety of assessment tools have been used to confirm the outcomes of treatment programs for PFM disorders. Aksac et al. [65] used as outcome measures: digital palpation and vaginal pressure measurement of PFM, 1-h pad test, incontinence frequency, index of social activity, and visual analog scale, whereas Burns et al. [67] used urodynamic parameters (i.e., maximal urethral pressure, functional urethral length), EMG pelvic muscle activity, and 24-h bladder diary. The heterogeneity of the studies has been a limiting factor for the conclusion of this study.

With regards to studies that compared PFMT with BF and electrical stimulation, none were included in the pooled effects calculation. In the evaluation of quality of life, two studies used the King’s Health Questionnaire, although, as mentioned above, the calculation of the score was performed differently. Schmidt et al. [60] calculated the total score and did not find a significant difference among the groups. Wang et al. [61] calculated the domains separately, and the data between the PFMT with BF group and the electrical stimulation group revealed statistically significant differences with respect to the emotions (p = 0.003) and severity (p = 0.029) domains, but not in the total score (p = 0.952). Demirtürk et al. [59] found an improved quality of life in both modalities (p < 0.05). Each of these studies evaluated outcomes in the short term.

Regarding symptom evaluation, one study opted not to use episodes of leakage per day due to the large number of incomplete records, which could bias the results [61]. Two studies found significant decreases in the number of stress leakages assessed by the bladder diary and pad test (p < 0.05) [59, 60] in the short term. Another study compared PFMT with BF, low-intensity electrical stimulation at home, and maximal electrical stimulation in the clinic. There were significant reductions in urine loss for all three groups after 6 months of treatment; however, the strongest evidence for improvement occurred in the clinical treatment group (p = 0.0003) in the intermediate term. In the long term, all groups demonstrated a further reduction in urine loss at pad testing.

For PFM evaluation, two studies found improvements after treatment in each group, and both treatment modalities seemed to have similar effects on PFM evaluation [59, 60]. Wang et al. [61] found improvement in vaginal pressure for the PFMT with BF group, demonstrating a 105 % increase after treatment, whereas electrical stimulation only yielded an increase of 12.63 %. However, the authors stated that muscle strength is not a good measurement of overactive bladder, and the preferred measurement of overactive bladder might be an evaluation of urinary symptom reduction or improvement in quality of life.

With regard to the studies in which PFMT with BF was used as treatment for anorectal dysfunction, no studies were included in the pooled results calculation due to the inability to extract the mean and standard deviation values for analysis. In the comparison between BF and electrical stimulation, Naimy et al. [72] found no difference between groups regarding quality of life, symptoms of anal incontinence, and subjective perceptions of incontinence control. In two studies, BF was compared with BF and electrical stimulation for fecal incontinence, and the results between the two studies were divergent. Mahony et al. [71] did not find any additional benefit of electrical stimulation on symptom outcome. However, Fynes et al. [70] found that the outcome for the BF group with electrical stimulation was superior to that of the group that used BF alone. This may have occurred because Mahony et al. [71] used stimulation frequencies of approximately 35 Hz, whereas Fynes et al. [70] used both smaller frequencies (about 20 Hz) and larger frequencies (about 50 Hz).

In studies wherein PFMT with BF was used to treat sexual dysfunction, only one presented the results in mean and standard deviation. These studies were not included because the aim of this review was to combine many studies to determine pooled results. Both studies included in this review treated vestibular pain. Only the results of the comparison between the conservative interventions are discussed. All studies found significant improvements in measurements posttreatment. In the study by Bergeron et al. [73], both the PFMT with BF and cognitive behavioral therapy groups showed significant improvements in psychological adjustment and sexual functioning at a 6-month follow-up, persisting up to the 2-year follow-up. One factor that may be responsible for these results is the fact that, in both groups, Kegel exercises were conducted. In the cognitive behavioral therapy group, the exercises were not practiced with the same intensity as in the PFMT with BF group. The authors claim that training with BF reduces the instability and hypertonicity of the PFM. Reestablishment of muscle function with an improved capacity to relax the pelvic floor during sexual activity is thought to reduce coital pain. In another study, PFMT with BF was compared with lidocaine treatment. Despite the high dropout rate in the PFMT with BF group, Danielsson et al. [74] found that there were significant improvements in both groups after treatment. Thus, if the PFMT with BF group had had better compliance with the treatment, the result could have been more satisfactory. Indeed, patient compliance is very important, as the effect of the treatment is dependent on it, which has been demonstrated in several previous studies [78–80].

Unfortunately it was not possible to perform the calculation of effect size by reviewing studies that address the treatment of sexual and anorectal dysfunction. A major reason was the number of included studies. Nevertheless, we would like to emphasize the necessity of randomized, controlled, and well-designed studies assessing the use of BF to treat these disorders and the need to conduct new research which, when considered together, will be able to achieve a conclusion.

Patient compliance is considered important in physical therapy, as treatment effects are partially dependent on it. The efficacy of therapeutic exercises can only be established when patients adhere to the exercise regimen [81]. Patients adhere better to treatment when they perceive no barriers, are extensively instructed, and receive positive feedback [82]. In the studies included in this review, only one study reported 100 % adherence [55]. As previously mentioned, BF is used as a technique that provides motivation for patients to perform PFM exercises and as a form of awareness of the PFMs. For PFMT with BF, the patient’s awareness of PFM is critical, as conscious activation of PFMs is a requirement for strength training [58].

There are some limitations to the conclusions of this review. These include the low quality of the studies, the use of various types of outcomes, and the differences in the implementation of the interventions. The results of this systematic review suggest that PFMT with BF is not more effective than other conservative treatments for female PFM dysfunction.

Abbreviations

- BF:

-

Biofeedback

- PFMT:

-

Pelvic floor muscle training

- PFM:

-

Pelvic floor muscle

References

Smith CA, Witherow RO (2000) The assessment of female pelvic floor dysfunction. BJU Int 85:579–587

Bø K, Sherburn M (2007) Introduction. In: Bø K, Berghmans B, Mørkved S, Van Kampen M (eds) Evidence-based physical therapy for the pelvic floor, 1st edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 47–49

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D et al (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:116–126

Glavind K, Nøhr S, Walter S (1992) Pelvic floor training using biofeedback for muscle awareness in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: preliminary results. Int Urgoynecol J 3:288–291

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS et al (1998) Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 280:1995–2000

Bø K (2007) Pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence. In: Bø K, Berghmans B, Mørkved S, Van Kampen M (eds) Evidence-based physical therapy for the pelvic floor, 1st edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 171–186

Kegel AH (1948) Progressive resistance exercise in the functional restoration of the perineal muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 56(2):238–248

Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Moseley AM (2000) PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man Ther 5:223–226

Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) (2011) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). In: The Cochrane Collaboration. Available via www.cochrane-handbook.org

Review Manager (RevMan) (computer program). Version 5.1 (2011) The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen

Meyer S, Hohlfeld P, Achtari C, De Grandi P (2001) Pelvic floor education after vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 97(5 Pt 1):673–677

Lee IS, Choi ES (2006) Pelvic floor muscle exercise by biofeedback and electrical stimulation to reinforce the pelvic floor muscle after normal delivery. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi 36(8):1374–1380

Gallo ML G, Staskin DR (1997) Cues the action: pelvic floor muscle exercise compliance in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 16(3):167–177

Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL et al (2002) Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2293–2299

Hui E, Lee PS, Woo J (2006) Management of urinary incontinence in older women using videoconferencing versus conventional management: a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 12(7):343–347

Wong KS, Fung KS, Fung SM, Fung CW, Tang CH (2001) Biofeedback of pelvic floor muscles in the management of genuine stress incontinence in Chinese women: randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy 87(12):644–648

Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS (2000) Combined behavioral and drug therapy for urge incontinence in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 48:370–374

Bocassanta P, Venturini M, Salamina G, Cesana BM, Bernasconi F, Roviaro G (2004) New trends in the surgical treatment of outlet obstruction: clinical and functional results of two novel transanal stapled techniques from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 19(4):359–369

Goode PS (2004) Behavioral and drug therapy for urinary incontinence. Urology 63(3 Suppl 1):58–64

Ilnyckyj A, Fachnie E, Tougas G (2005) A randomized-controlled trial comparing an educational intervention alone vs education and biofeedback in the management of faecal incontinence in women. Neurogastroenterol Motil 17:58–63

Sherman RA, Davis GD, Wong MF (1997) Behavioral treatment of exercise-induced urinary incontinence among female soldiers. Mil Med 162:690–694

Wang AC (2000) Bladder-sphincter biofeedback as treatment of detrusor instability in women who failed to respond to oxybutynin. Chang Gung Med J 23(10):590–599

Castleden CM, Duffin HM, Mitchell EP (1984) The effect of physiotherapy on stress incontinence. Age Ageing 13:235–237

Cammu H, Van Nylen M (1998) Pelvic floor exercises versus vaginal cones in genuine stress incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 77:89–93

Knight S, Laycock J, Naylor D (1998) Evaluation of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in the treatment of genuine stress incontinence. Physiotherapy 84(2):61–71

Glavind K, Nøhr SB, Walter S (1996) Biofeedback and physiotherapy versus physiotherapy alone in the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 7:339–343

Oresland T, Fasth S, Hultén L, Nordgren S, Swenson L, Akervall S (1988) Does balloon dilatation and anal sphincter training improve ileonal-pouch function? Int J Colorectal Dis 3(3):153–157

Miner PB, Donnelly TC, Read NW (1990) Investigation of mode of action of biofeedback in treatment of fecal incontinence. Dig Dis Sci 35(10):1291–1298

Awad R (1994) Biofeedback in the treatment of fecal incontinence. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 59(2):171–176

Enck P, Däublin G, Lübke HJ, Strohmeyer G (1994) Long-term efficacy of biofeedback training for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 37(10):997–1001

Bleijenberg G, Kuijpers HC (1994) Biofeedback treatment of constipation: a comparison of two methods. Am J Gastroenterol 89(7):1021–1026

Koutsomanis D, Lennard-Jones JE, Roy AJ, Kamm MA (1995) Controlled randomised trial of visual biofeedback versus muscle training without a visual display for intractable constipation. Gut 37(1):95–99

Guillemot F, Bouche B, Gower-Rousseau C et al (1995) Biofeedback for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Long-term clinical results. Dis Colon Rectum 38(4):393–397

Hämäläinen KJ, Raivio P, Antila S, Palmu A, Mecklin JP (1996) Biofeedback therapy in rectal prolapse patients. Dis Colon Rectum 39(3):262–265

Engberg S, McDowel BJ, Donovan N, Brodak I, Weber E (1997) Treatment of urinary incontinence in homebound older adults: interface between research and practice. Ostomy Wound Manage 43(10):18–22

Heymen S, Wexner SD, Vickers D, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Pikarsky AJ (1999) Prospective, randomized trial comparing four biofeedback techniques for patients with constipation. Dis Colon Rectum 42(11):1388–1393

Glia A, Gylin M, Gullberg K, Lindberg G (1997) Biofeedback retraining in patients with functional constipation and paradoxical puborectalis contraction: comparison of anal manometry and sphincter electromyography for feedback. Dis Colon Rectum 40(8):889–895

Pager CK, Solomon MJ, Rex J, Roberts RA (2002) Long-term outcomes of pelvic floor exercise and biofeedback treatment for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 45(8):997–1003

Norton C, Chelvanayagana S, Wilson-Barnett J, Redfern S, Kamm MA (2003) Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 125(5):1320–1329

Solomon MJ, Pager CK, Rex J, Roberts R, Manning J (2003) Randomized, controlled trial of biofeedback with anal manometry, transanal ultrasound, or pelvic floor retraining with digital guidance alone in the treatment of mild to moderate fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 46(6):703–710

Chang HS, Myung SJ, Yang SK et al (2003) Effect of electrical stimulation in constipated patients with impaired rectal sensation. Int J Colorectal Dis 18(5):433–438

Chiaroni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassoti G (2006) Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology 130(3):657–664

Norton C, Gibbs A, Kamm MA (2006) Randomized, controlled trial of anal electrical stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 49(2):190–196

Byrne CM, Solomon MJ, Young JM, Rex J, Merlino CL (2007) Biofeedback for fecal incontinence: short-term outcomes of 513 consecutive patients and predictors of successful treatment. Dis Colon Rectum 50(4):417–427

Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, Ringel Y, Drossman D, Whitehead WE (2007) Randomized, controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Dis Colon Rectum 50(4):428–441

Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller M et al (2007) Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5(3):331–338

Remes-Troche JM, Ozturk R, Philips C, Stessman M, Rao SS (2008) Cholestyramine—a useful adjunct for the treatment of patients with fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis 23(2):189–194

Simón MA, Bueno AM (2009) Behavioural treatment of the dyssynergic defecation in chronically constipated elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 34(4):273–277

Faried M, El Monem HA, Omar M et al (2009) Comparative study between biofeedback retraining and botulinum neurotoxin in the treatment of anismus patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 24(1):115–120

Schwandner T, König IR, Heimerl T et al (2010) Triple target treatment (3T) is more effective than biofeedback alone for anal incontinence: the 3T-AI study. Dis Colon Rectum 53(7):1007–1016

Rao SS, Valestin J, Brown CK, Zimmerman B, Schulze K (2010) Long-term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 105(4):890–896

Faried M, El Nakeeb A, Youssef M, Omar W, El Monem HA (2010) Comparative study between surgical and non-surgical treatment of anismus in patients with symptoms of obstructed defecation: a prospective randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg 14(8):1235–1243

Engberg S, McDowell BJ, Weber E, Brodak I, Donovan N, Engberg R (1997) Assessment and management of urinary incontinence among homebound older adults: a clinical trial protocol. Adv Pract Nurs Q 3(2):48–56

Burns PA, Pranikoff K, Nochajski T, Desotelle P, Harwood MK (1990) Treatment of stress incontinence with pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback. J Am Geriatr Soc 38(3):341–344

Berghmans LCM, Frederiks CMA, de Bie RA, Weil EHJ, Smeets LWH, van Waalwijk van Doorn ESC, Janknegt RA (1996) Efficacy of biofeedback, when included with pelvic floor muscle exercise treatment, for genuine stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 15:37–52

Mørkved S, Bø K, Fjortoft T (2002) Effect of adding biofeedback to pelvic floor muscle training to treat urodynamic stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 100(4):730–739

Ferguson KL, McKey PL, Bishop KR, Kloen P, Verheul JB, Dougherty MC (1990) Stress urinary incontinence: effect of pelvic muscle exercise. Obstet Gynecol 75(4):671–675

Pages IH, Jahr S, Schaufele MK, Conradi E (2001) Comparative analysis of biofeedback and physical therapy for treatment of urinary stress incontinence in women. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 80:494–502

Demirtürk F, Akbayrak T, Karakaya IC et al (2008) Interferential current versus biofeedback results in urinary stress incontinence. Swiss Med Wkly 138(21–22):317–321

Schmidt AP, Sanches PRS, Silva DP, Ramos JGL, Nohama P (2009) A new pelvic muscle trainer for the treatment of urinary incontinence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105:218–222

Wang AC, Wang YY, Chen MC (2004) Single-blind, randomized trial of pelvic floor muscle training, biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training, and electrical stimulation in the management of overactive bladder. Urology 63:61–66

Wyman JF, Fantl JA, McClish DK, Bump RC (1998) Comparative efficacy of behavioral interventions in the management of female urinary incontinence. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179(4):999–1007

Laycock J, Brown J, Cusack C et al (2001) Pelvic floor reeducation for stress incontinence: comparing three methods. Br J Community Nurs 6(5):230–237

Dougherty MC, Dwyer JW, Pendergast JF et al (2002) A randomized trial of behavioral management for continence with older rural women. Res Nurs Health 25:3–13

Aksac B, Aki S, Karan A, Yalcin O, Isikoglu M, Eskiyurt N (2003) Biofeedback and pelvic floor exercises for the rehabilitation of urinary stress incontinence. Gynecol Obstet Invest 56:23–27

Shepherd AM, Montgomery E, Anderson RS (1983) Treatment of genuine stress incontinence with a new perineometer. Physiotherapy 69(4):113

Burns PA, Pranikoff K, Nochajski TH, Hadley EC, Levy KJ, Ory MG (1993) A comparison of effectiveness of biofeedback and pelvic muscle exercise treatment of stress incontinence in older community-dwelling women. J Gerontol 48(4):M167–M174

Aukee P, Immonem P, Penttinen J, Laippala P, Airaksinen O (2002) Increase in pelvic floor muscle activity after 12 weeks’ training: a randomized prospective pilot study. Urology 60(6):1020–1023

Aukee P, Immonen P, Laaksonen DE, Laippala P, Penttinen J, Airaksinen O (2004) The effect of home biofeedback training on stress incontinence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 83:973–977

Fynes MM, Marshall K, Cassidy M et al (1999) A prospective, randomized study comparing the effect of augmented biofeedback with sensory biofeedback alone on fecal incontinence after obstetric trauma. Dis Colon Rectum 42:753–761

Mahony RT, Malone PA, Nalty J, Behan M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C (2004) Randomized clinical trial of intra-anal electromyographic biofeedback physiotherapy with intra-anal electromyographic biofeedback augmented with electrical stimulation of the anal sphincter in the early treatment of postpartum fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:885–890

Naimy N, Lindam AT, Bakka A et al (2007) Biofeedback vs. electrostimulation in the treatment of postdelivery anal incontinence: a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum 50:2040–2046

Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalifé S et al (2001) A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain 91:297–306

Danielsson I, Torstensson T, Brodda-Jansen G, Bohm-Starke N (2006) EMG biofeedback versus topical lidocaine gel: a randomized study for the treatment of women with vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol 85:1360–1367

Bergeron S, Khalifé S, Glazer HI, Binik YM (2008) Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol 111(1):159–166

Bohm-Starke N, Brodda-Jansen G, Linder J, Danielsson I (2007) The result of treatment on vestibular and general pain thresholds in women with provoked vestibulodynia. Clin J Pain 23:598–604

Berghmans LCM, Bernards ATM, Hendriks HLM et al (1998) Guidelines for the physiotherapeutic management of genuine stress incontinence. Phys Ther Rev 3(3):133–147

Bø K, Talseth T (1996) Long-term effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise 5 years after cessation of organized training. Obstet Gynecol 87:261–265

Chen HY, Chang WC, Lin WC et al (1999) Efficacy of pelvic floor rehabilitation for treatment of genuine stress incontinence. J Formos Med Assoc 98:271–276

Lagro-Janssen ALM, van Weel C (1998) Long-term effect of treatment of female incontinence in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 48:1735–1738

Sluijs EM, Knibbe JJ (1991) Patient compliance with exercise: different theoretical approaches to short-term and long-term compliance. Patient Educ Couns 17:191–204

Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J (1993) Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther 73(11):771–782

Pescatori M, Anastasio G, Bottini C, Mentasti A (1992) New grading and scoring for anal incontinence. Evaluation of 335 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 35:482–487

Dougherty MC, Bishop KR, Abrams RM, Batich CD, Gimotty PA (1989) The effect of exercise on the circumvaginal muscles in postpartum women. J Nurse Midwifery 34:8–14

Wyman JF, Fantl JA (1991) Bladder training in ambulatory care management of urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs 11(3):11–7

Bø K, Kvarstein B, Hagen R, Larsen S (1990) Pelvic floor muscle exercise for the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 9:471–7

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) research foundation, grant nº 153287/2010-1.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Search strategies

PEDro

Therapy: no selection

Problem: incontinence

Body part: perineum or genitourinary system

Subdiscipline: continence and women’s health

Method: clinical trial

Match all search terms (AND)

Therapy: no selection

Problem: motor incoordination

Body part: perineum or genitourinary system

Subdiscipline: continence and women’s health

Method: clinical trial

Match all search terms (AND)

Therapy: no selection

Problem: muscle weakness

Body part: perineum or genitourinary system

Subdiscipline: no selection

Method: clinical trial

Match all search terms (AND)

MEDLINE/LILACS

1. ((biofeedback and (muscle and pelvic and floor))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

2. ((biofeedback and (urinary and incontinence))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

3. ((biofeedback and (urinary and incontinence and muscle and pelvic and floor))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

4. ((biofeedback and (stress and urinary and incontinence))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

5. (biofeedback and (overactive and bladder))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

6. ((biofeedback and pelvic and floor and exercises)) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

7. ((biofeedback and neuromuscular and electrical and stimulation)) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

8. ((biofeedback and (fecal and incontinence))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

9. ((biofeedback and (anal and incontinence))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

10. ((biofeedback and (anal and incontinence and muscle and pelvic and floor))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

11. ((biofeedback and (fecal and incontinence and muscle and pelvic and floor))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

12. ((biofeedback and (intestinal and constipation))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

13. ((biofeedback and (constipation))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

14. ((biofeedback and (dyspareunia))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

15. ((biofeedback and (sexual and dysfunction))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

16. ((biofeedback and (sexual))) AND ([CT] humano or humanos) AND ([CT] FEMININO) AND ([PT] ENSAIO CLINICO CONTROLADO OR ENSAIO CONTROLADO ALEATORIO) [Palavras]

17. biofeedback and (vaginismus) AND Espécie = Humanos AND Gênero = Feminino AND Tipo de publicação = Ensaio clínico controlado

PubMed

1. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("pelvic floor"[MeSH Terms] OR ("pelvic"[All Fields] AND "floor"[All Fields]) OR "pelvic floor"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

2. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("muscles"[MeSH Terms] OR "muscles"[All Fields] OR "muscle"[All Fields]) AND ("pelvic floor"[MeSH Terms] OR ("pelvic"[All Fields] AND "floor"[All Fields]) OR "pelvic floor"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

3. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("urinary incontinence"[MeSH Terms] OR ("urinary"[All Fields] AND "incontinence"[All Fields]) OR "urinary incontinence"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

4. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("urinary incontinence, stress"[MeSH Terms] OR ("urinary"[All Fields] AND "incontinence"[All Fields] AND "stress"[All Fields]) OR "stress urinary incontinence"[All Fields] OR ("stress"[All Fields] AND "urinary"[All Fields] AND "incontinence"[All Fields]))) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

5. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("urinary bladder, overactive"[MeSH Terms] OR ("urinary"[All Fields] AND "bladder"[All Fields] AND "overactive"[All Fields]) OR "overactive urinary bladder"[All Fields] OR ("overactive"[All Fields] AND "bladder"[All Fields]) OR "overactive bladder"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

6. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("exercise"[MeSH Terms] OR "exercise"[All Fields]) AND ("pelvic floor"[MeSH Terms] OR ("pelvic"[All Fields] AND "floor"[All Fields]) OR "pelvic floor"[All Fields]) AND ("muscles"[MeSH Terms] OR "muscles"[All Fields] OR "muscle"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

7. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND neuromuscular[All Fields] AND ("electric stimulation"[MeSH Terms] OR ("electric"[All Fields] AND "stimulation"[All Fields]) OR "electric stimulation"[All Fields] OR ("electrical"[All Fields] AND "stimulation"[All Fields]) OR "electrical stimulation"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

8. (#6) AND #4 AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

9. (#6) AND #3 AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

10. (#7) AND #3 AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

11. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("faecal incontinence"[All Fields] OR "fecal incontinence"[MeSH Terms] OR ("fecal"[All Fields] AND "incontinence"[All Fields]) OR "fecal incontinence"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

12. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND anal[All Fields] AND ("urinary incontinence"[MeSH Terms] OR ("urinary"[All Fields] AND "incontinence"[All Fields]) OR "urinary incontinence"[All Fields] OR "incontinence"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized

13. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("sexual behavior"[MeSH Terms] OR ("sexual"[All Fields] AND "behavior"[All Fields]) OR "sexual behavior"[All Fields] OR "sexual"[All Fields]) AND ("physiopathology"[Subheading] OR "physiopathology"[All Fields] OR "dysfunction"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

14. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("dyspareunia"[MeSH Terms] OR "dyspareunia"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

15. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("constipation"[MeSH Terms] OR "constipation"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

16. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("intestines"[MeSH Terms] OR "intestines"[All Fields] OR "intestinal"[All Fields]) AND ("constipation"[MeSH Terms] OR "constipation"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

17. (("biofeedback, psychology"[MeSH Terms] OR ("biofeedback"[All Fields] AND "psychology"[All Fields]) OR "psychology biofeedback"[All Fields] OR "biofeedback"[All Fields]) AND ("pelvic floor"[MeSH Terms] OR ("pelvic"[All Fields] AND "floor"[All Fields]) OR "pelvic floor"[All Fields]) AND ("muscles"[MeSH Terms] OR "muscles"[All Fields] OR "muscle"[All Fields]) AND ("physiopathology"[Subheading] OR "physiopathology"[All Fields] OR "dysfunction"[All Fields])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

18. (#14) AND #6 AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

19. (#15) AND #6 AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND "female"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp])

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fitz, F.F., Resende, A.P.M., Stüpp, L. et al. Biofeedback for the treatment of female pelvic floor muscle dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 23, 1495–1516 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1707-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1707-1