Abstract

We conducted an audit to evaluate how effective a structured course in the management of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) was at imparting knowledge. Training was undertaken using models and cadaveric pig’s anal sphincters. An anonymous questionnaire was completed prior to and 8 weeks after the course. Four hundred and ninety seven completed the questionnaire before and 63% returned it after the course. Prior to the course, participants performed on average 14 OASIS repairs independently. Only 13% were satisfied with their level of experience prior to performing their first unsupervised repair. After the course, participants classified OASIS more accurately and changed to evidence-based practice. Particularly, there was a change in identifying (60% vs. 90%; P < 0.0001) and repairing the internal sphincter (60% vs. 90%; P < 0.0001). This audit demonstrated that training in the management of OASIS is suboptimal. Structured training may be effective in changing clinical practice and should be an adjunct to surgical training.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) occur in 1.7% (2.9% in primiparae) [1] of women in centres where mediolateral episiotomies are practised compared to 12% [2] (19% in primiparae [3]) in centres practising midline episiotomy. Unfortunately, it has been shown previously that up to half of OASIS are not recognised by the accoucher [4, 5]. Inadequate training of doctors and midwives in perineal and anal sphincter anatomy [6] is believed to be a major contributing factor. In a survey of 75 doctors and 75 midwives in the UK, Sultan et al. demonstrated inconsistencies in the classification of perineal trauma, as one third of doctors were classifying third degree tears as second degree tears [6]. Most trainee doctors admitted that their training in recognising (84%) and repairing (94%) OASIS was poor. Furthermore, in another study, 64% of consultants reported unsatisfactory or no training in the management of OASIS [7]. McLennan et al. also raised concern about training in the USA. They surveyed 1,177 fourth year residents and found that the majority of residents had received no formal training in pelvic floor anatomy, episiotomy or perineal repair, and supervision during perineal repair was limited [8].

However, despite recognition and primary repair of acute OASIS, 39% to 61% [9–11] have symptoms of anal incontinence and 92% have persistent anal sphincter defects on ultrasound [12] within 3 months of delivery. The morbidity associated with perineal trauma depends on the extent of perineal damage, technique and materials used for suturing and the skill of the person performing the procedure. It is therefore important that practitioners ensure that procedures such as perineal repair are evidence based in order to provide care which is effective, appropriate and cost efficient [13].

In view of this, we initiated the first international hands-on workshop on the management of OASIS to educate obstetricians in perineal and anal sphincter anatomy and techniques of repair of OASIS. The aim of this study was to audit the effect of a structured hands-on workshop on the knowledge and management of OASIS.

Materials and methods

A hands-on workshop on repair of OASIS was set up and advertised on the internet (www.perineum.net) and the newsletter of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). This 1-day course comprised of a series of lectures, video demonstrations on repair techniques and identification of OASIS, and hands-on training using a specially designed latex perineal model (Limbs & Things®) (Fig. 1) and cadaveric pig’s anal sphincters. Practical training (Fig. 2) included identifying and separate repair of the torn internal anal sphincter (IAS) using mattress end-to-end sutures with polydioxanone (PDS) sutures and both the end-to-end and overlap repair techniques of the external anal sphincter (EAS). All candidates attending the 1-day course on the management of OASIS completed an anonymous questionnaire prior to the course (Table 1). A repeat questionnaire was mailed 8 weeks after the course with a second mailing to non-responders 4 weeks later.

Sultan anal sphincter latex training model with the replacement block. A anal epithelium, I internal anal sphincter, E external anal sphincter (www.perineum.net)

Photograph of fresh fourth degree tear that can be compared to Fig. 1. AM anorectal epithelium, I internal anal sphincter that is paler than the external sphincter (E)

All data was entered onto a Microsoft® Excel spreadsheet. To investigate the change in dependent proportions, a McNemar test was used, and to compare proportions in independent groups, the chi square test was used using SPSS version 15.0.

Results

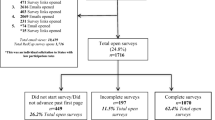

Eleven courses were conducted between August 2001 and May 2004. Four hundred and ninety seven doctors completed the pre-course questionnaire and 311 (63%) returned a post-course questionnaire. The majority were practising obstetricians in the UK and 27 (5%) were working overseas. Of those that completed the questionnaire, 101 (20%) were senior house officers, 266 (59%) specialist registrars, 22 (5%) staff grades and 59 (13%) consultants. Prior to the course, participants had performed a mean of five supervised and 14 repairs of OASIS independently; consultants attending were more experienced having on average performed ten repairs under supervision and 47 independently. Three hundred and fifty two (79%) worked in units that had a labour ward protocol for the management of OASIS. Two hundred and fifty five participants answered a question on their training; of those that did, 74 (29%) felt their training was poor or very poor, 140 (55%) said it could be better and only 41 (16%) were satisfied with their level of experience prior to performing their first unsupervised repair.

There was a significant change in practice amongst obstetricians after attending the hands-on workshop (Table 2). In addition, obstetricians were able to classify OASIS more accurately after attending the course (Table 3).

A breakdown of consultant and non-consultant grade doctors demonstrated that their knowledge of the classification of OASIS prior to the course was similar; however, fewer consultants than trainees routinely repaired OASIS in the operating theatre, gave antibiotic prophylaxis or used PDS sutures for the repair of these injuries (Table 4).

Discussion

In this questionnaire-based survey, we have demonstrated that a hands-on OASIS course appeared to change clinical practice to the best available evidence-based care at that time. In addition, this course also significantly improved the obstetrician’s knowledge of anatomy and the correct classification of anal sphincter injuries.

The majority of obstetricians attending the workshop were trainee doctors with at least 5 years clinical experience. More than 80% of participants felt that their training prior to performing OASIS repairs independently was unsatisfactory. These findings concur with the study of Sultan et al. [6] who in an interview-based study identified that only 20% of junior doctors considered their training to be of a good standard when performing their first unsupervised perineal repair. Up to 25% of women having their first vaginal birth sustain OASIS [5]. It is therefore mandatory that trainee obstetricians are taught early in their career to identify and repair OASIS. It is surprising that, despite episiotomy being the most common operation in obstetrics, training in perineal anatomy and repair has been inadequate. Two publications, one from the UK [10] and the other from the USA [14], found that popular textbooks in obstetrics and gynaecology offered little information in terms of diagnosis, repair and prevention of perineal trauma.

There appeared to be a significant change in practice after attending the course with significantly more doctors attempting to identify and repair the IAS separately and learning to perform an overlap repair of the EAS. Delegates attending the workshop were taught both the overlap and the end-to-end technique of EAS repair. A recent Cochrane review [15] including three randomised studies [16–18] compared end-to-end versus the overlap technique to repair the EAS showed that early primary overlap appears to be associated with lower risks of faecal urgency and anal incontinence symptoms. However, as the experience of the surgeon was only addressed in one [16] of the three studies reviewed, there was a reluctance to recommend one type of repair over the other. However, two studies included partially torn EAS (grade 3a) in their randomised trial [17, 18] and in one study [18] more than 70% of the women included in the randomised trial were grade 3a. A true overlap [21] cannot be performed if the EAS is only partially torn as the repair would be under tension and this would be against general surgical principles [9]. Furthermore, in one study, the follow-up rate at 12 months was only 54% [18]. Fernando et al. [16] performed a randomised trial of end-to-end vs. overlap technique in which all repairs were performed by two trained operators. However, unlike the other studies [17, 18], all repairs were done on a completely divided external sphincter. At 12 months, 24% in the end-to-end and none in the overlap group reported faecal incontinence (p = 0.009). Faecal urgency at 12 months was reported by 32% in the end-to-end and 3.7% in the overlap group (p = 0.02). Further calculation revealed that four women need to be treated with the overlap technique to prevent one woman with OASIS developing faecal incontinence.

At the time of the study based on expert evidence [10, 19] PDS was recommended as the ideal suture material and therefore PDS was used to repair the EAS and IAS. More recently, Williams et al. [18] conducted a randomised trial and reported no differences in suture related morbidity (need for suture removal due to pain, suture migration or dyspareunia) when PDS or Vicryl suture material was used.

The RCOG guidelines on the management of third and fourth degree perineal tears recommend that, where possible, the IAS should be identified and repaired separately [20]. It has been previously demonstrated that when the IAS is separately identified it can be repaired successfully [21, 22]. In a recent blinded randomised study of repair after OASIS, all nine women who had a repair of an IAS tear (grade 3c or fourth degree) were found to have an intact IAS at follow-up using anal endosonography [9, 16]. Until highlighted by Sultan et al. [21], identification and primary repair of the IAS (Fig. 2) was not described in the literature [10]. Another publication from the USA surveyed residents before and after an educational workshop on the performance of fourth degree perineal lacerations using the same model that was used in this study (Fig. 1) and demonstrated that approximately 81% of all residents, including 35% of senior residents, failed the assessment because they could not recognise the IAS and therefore made no attempt to repair it [23]. After the workshop, all residents passed their subsequent assessment.

A previous small study of 56 women who sustained OASIS has shown that the presence of a combined IAS and EAS defect was significantly related to bowel symptoms 6 to 8 weeks post-partum [24]. Furthermore, an association between persistent IAS defects after OASIS and severe symptoms of faecal incontinence has been demonstrated [22]. Unfortunately, if an IAS injury persists (due either to non-diagnosis or a poor repair at delivery), the woman has lost her chance of successful repair as colorectal experts are of the view that it is almost impossible to perform a secondary repair of the IAS [25]. This highlights the importance of training of obstetricians in identifying and repairing the IAS adequately at delivery.

More trainees took patients to theatre where adequate lighting, access to appropriate surgical instruments and aseptic technique are easier to achieve than in the delivery rooms. In addition, trainees were likely to give antibiotic prophylaxis and use monofilament suture for repairing the anal sphincter. This may be a reflection of the attention given to the management of OASIS in the current training of specialists in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the RCOG guidelines [20, 26] and formal assessment of trainees knowledge of perineal trauma by way of objective structured assessment of technical skills (OSATS).

Our results concur with those of Siddighi et al. [23] who demonstrated that residents in Obstetrics and Gynaecology who underwent a structured training workshop improved their surgical ability in their management of OASIS. They demonstrated this objectively using OSATS which is a valid and reliable method of measuring skills and has been validated in different obstetric and gynaecological procedures [27].

We acknowledge the limitations of this study in that it is questionnaire based and does not identify core competencies using task-specific and global assessment tools. As the survey was not patient centred, the results of this survey should be interpreted with caution. It is possible that the results indicate that the attending participants were able to remember the recommendations (retention) but we do not know if clinical practice actually changed (transfer). To evaluate the true impact of such a course, a randomised controlled trial of outcome for women managed by trainees who attended such a workshop should be compared to those who received no formal in the management of OASIS. As the participants attend from many different centres in the world, it is difficult to evaluate the outcome of the patients who were subsequently sutured by the participants. However, trainees are advised to keep a logbook of procedures performed, and it would be expected from individuals to audit their outcome of OASIS repairs. The recent trainee logbook developed by the RCOG includes an OSAT on perineal trauma and this kind of training method should help to some extent in the individual assessment of trainees on a one-to-one basis. Another limitation of this survey is that no data was collected on the 37% who did not complete the questionnaire. It is possible that more enthusiastic participants completed the questionnaire. Hence, we acknowledge that we may have overestimated the effect of the course on the change in clinical practice. We are unable to test the long-term effects of our intervention as the repeat questionnaire was sent out 8 weeks after the course. Long-term evaluation is difficult as most trainees in the UK tend to rotate to different hospitals at least on an annual basis. We hope to overcome this problem by sending emails to participants after 1 year in the future. Some participants who returned the questionnaire did not answer every question; this is perhaps because the questionnaire had not been subjected to a validation process. Further work to address this is underway in our unit so that the questionnaire can be used by other groups who run similar courses.

The Sultan anal sphincter trainer model (Fig. 1) was developed in response to the need for training [6, 7]. With the decline in forceps deliveries and reduction in trainees’ working hours, trainees acquire less experience in the repair of perineal suturing. In addition, the occurrence of OASIS is unpredictable and unplanned. Opportunities for trainees to repair these injuries under authentic circumstances are few. Training and testing on commercial models may be helpful in enhancing the acquisition of technical skills. Although the Sultan anal sphincter training model (Fig. 1) may be considered expensive, its price is in keeping with that of other teaching models but the cost is offset by the versatility and low cost of the replacement blocks that can be reused many times. However, other models such as the “sponge perineum” have also been used [28]. The advantage of inanimate models includes availability and portability. In addition to the model (Fig. 1), we use the pig anal sphincter (Fig. 2) to help the participants dissect and identify the layers of the anal sphincter (IAS, conjoint longitudinal coat and EAS). The pig anal sphincter has a realistic texture and appearance similar to the human’s but it is more time consuming to prepare and one has to be mindful of the health and safety, ethical, religious and moral issues when using animal tissue. With these developments, we hope that the traditional culture of “see one, do one, teach one” will be abandoned.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that knowledge of obstetricians attending the workshop in perineal anatomy and repair is suboptimal and that hands-on workshops can improve clinical practice. In particular, it highlights the importance of identifying and repairing the IAS at the time of initial injury as it is very difficult to repair, if at all, at a later date [25]. Structured, focused and hands-on education in technical skills relating to perineal repair should be included in all training programmes. While we believe that such a hands-on training course is important, this should be seen as an adjunct and not a substitute to surgical training under supervision by an experienced trainer in labour ward.

References

Harkin R, Fitzpatrick M, O’Connell PR, O’Herlihy C (1999) Anal sphincter disruption at vaginal delivery: is recurrence predictable. Eur J Obstet Gynaecol 106:318–323

Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ (1980) A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 87:408–412

Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Merril D, Zlatnik FJ (1999) Risk of repetition of a severe perineal laceration. Obstet Gynecol 93:1021–1024

Groom KM, Paterson-Brown S (2002) Can we improve on the diagnosis of third degree tears. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 101:19–21

Andrews V, Sultan AH, Thakar R, Jones PW (2006) Occult anal sphincter injuries—myth or reality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 113:195–200

Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN (1995) Obstetric perineal trauma: an audit of training. J Obstet Gynaecol 15:19–23

Fernando R, Sultan AH, Radley S, Jones PW, Johanson RB (2002) Management of obstetric anal sphincter injury: a systematic review and national practice survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2:9

Mc Lennan MT, Melick CF, Clancy SL, Artal R (2002) Episiotomy and perineal repair. J Reprod Med 47:1025–1030

Sultan AH, Thakar R (2007) Third and fourth degree tears. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE (eds) Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. Springer, London, pp 33–51

Sultan AH, Thakar R (2002) Lower genital tract and anal sphincter trauma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 16:99–115

Pinta TM, Kylanpaa M, Salmi TK, Teramo KAW, Luukkonen PS (2004) Primary sphincter repair: are the results of the operation good enough. Dis Colon Rectum 47:18–23

Fitzpatrick M, Cassidy M, O’Connell R, O’Herlihy C (2002) Experience with an obstetric perineal clinic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 100:199–203

Sultan AH, Kettle C (2007) Diagnosis of perineal trauma. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE (eds) Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. Springer, London, pp 13–19

Stepp KJ, Siddiqui NY, Emery SP, Barber MD (2006) Textbook recommendations for preventing and treating perineal injury at vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol 107:361–368

Fernando R, Sultan AH, Kettle C, Thakar R, Radley S (2006) Methods of repair for obstetric anal sphincter injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD002866

Fernando RJ, Sultan AH, Kettle C, Radley S, Jones P, O’Brien PMS (2006) Repair techniques for obstetric anal sphincter injuries. A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 107:1261–1268

Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O’Connell RP, O’Herlihy C (2000) A randomized clinical trial comparing primary overlap with approximation repair of third-degree obstetric tears. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:1220–1224

Williams A, Adams EJ, Tincello DG, Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA, Richmond DH (2006) How to repair an anal sphincter injury after vaginal delivery: results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 113:201–207

Norton C, Christiansen J, Butler U, Harari D, Nelson RL, Pemberton J, Price K, Rovnor E, Sultan A (2002) Anal incontinence. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury, Wein A (eds) Incontinence, 2nd edn. Health Publication, Plymouth, pp 985–1044

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2007) Third- and fourth-degree perineal tears—management. RCOG Guideline No. 29. RCOG, London

Sultan AH, Monga AK, Kumar D, Stanton SL (1999) Primary repair of obstetric anal sphincter rupture using the overlap technique. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 106:318–323

Mahony R, Behan M, Daly L, Kirwan C, O’Herlihy C, O’Connell PR (2007) Internal anal sphincter defect influences continence outcome following obstetric anal sphincter injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196:217.e1–217.e5

Siddighi S, Kleeman SD, Baggish MS, Rooney CM, Pauls RN, Karram MM (2007) Effects of an educational workshop on performance of fourth-degree perineal laceration repair. Obstet Gynecol 109:289–294

Nichols CM, Lamb EH, Ramakrishnan V (2005) Differences in outcomes after third- versus fourth-degree perineal laceration repair: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:530–534

Phillips RKS, Brown TJ (2007) Surgical management of anal incontinence. Secondary anal sphincter repair. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner DE (eds) Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. Springer, London, pp 144–153

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004) Methods and materials used in perineal repair. RCOG Guideline No. 23. RCOG, London

Goff BA, Lentz GM, Lee D, Morris J, Mandel LS (2000) Development of an objective structured assessment of technical skills for obstetrics and gynecology residents. Obstet Gynecol 96:146–150

Sparks RA, Beesley AD, Jones AD (2006) The “sponge perineum.” An innovative method of teaching fourth-degree obstetric perineal laceration repair to family medicine residents. Fam Med 38:542–544

Conflicts of interest

R.T. and A.H.S. designed the Sultan perineal model which is used in this course and by several others. No royalties are received from the sale of the Sultan perineal model, although 2% of the sale of the blocks is donated to the Mayday Childbirth Charity Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0986-7

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrews, V., Thakar, R. & Sultan, A.H. Structured hands-on training in repair of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS): an audit of clinical practice. Int Urogynecol J 20, 193–199 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0756-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0756-y