Abstract

Purpose

Revision of infected total knee replacements (TKR) is usually delayed for a period in which the joint space is filled with an antibiotic-loaded acrylic spacer. In contrast, one-stage re-implantation supposes immediate re-implantation. Formal comparisons between the two methods are scarce. A retrospective multi-centre study was conducted to investigate the effects of surgery type (one-stage vs. two-stage) on cure rates. It was hypothesised that this parameter would not influence the results.

Method

All infected TKR, treated consecutively between 2005 and 2010 by senior surgeons working in six referral hospitals, were included retrospectively. Two hundred and eighty-five patients, undergoing one-stage or two-stage TKR, with more than 2-year follow-up (clinical and radiological) were eligible for data collection and analysis. Of them, 108 underwent one-stage and 177 received two-stage TKR. Failure was defined as infection recurrence or persistence of the same or unknown pathogens. Factors linked with infection recurrence were analysed by uni- and multi-variate logistic regression with random intercept.

Results

Factors associated with infection recurrence were fistulae (odds ratio (OR) 3.4 [1.2–10.2], p = 0.03), infection by gram-negative bacteria (OR 3.3 [1.0–10.6], p = 0.05), and two-stage surgery with static spacers (OR 4.4 [1.1–17.9], p = 0.04). Gender and type of surgery interacted (p = 0.05). In men (133 patients), type of surgery showed no significant linkage with infection recurrence. In women (152 patients), two-stage surgery with static spacers was associated independently with infection recurrence (OR 5.9 [1.5–23.6], p = 0.01). Among patients without infection recurrence, International Knee Society scores were similar between those undergoing one-stage or two-stage exchanges.

Conclusion

Two-stage procedures offered less benefit to female patients. It suggests that one-stage procedures are preferable, because they offer greater comfort without increasing the risk of recurrence. Routine one-stage procedures may be a reasonable option in the treatment of infected TKR.

Level of evidence

III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Revision of infected total knee replacements (TKR) involves implant removal combined with bone and soft tissue excision, to eradicate all bacteria localised in implant surface biofilm and surrounding tissues. Re-implantation after septic revision is most often delayed for a more or less prolonged intermediate period, in which the joint space is filled with an antibiotic-loaded acrylic spacer. Conditions for re-implantation include prolonged and adapted anti-biotherapy, wound-healing and normalisation of all biological parameters [17]. This protocol provides infection eradication rates ranging from 60 to 100 % [8, 13, 26]. One drawback is the poor function offered by acrylic spacers in the intermediate period. In particular, articulated spacers are proposed in the hope of preserving range of motion [5, 6].

In contrast, one-stage revision supposes immediate re-implantation of new prosthetic devices during the same operative procedure for the removal of infected implants. This alternative method has the advantage of substantially shortening the surgical protocol and evoking less discomfort in patients. The main shortcoming is insufficient control of the initial infection at re-implantation time. However, clinical experiences have not revealed higher infection recurrence rates than two-stage revisions [3, 7, 15, 25].

Formal comparisons of both methods are scarce. In fact, multiple parameters may run interference, namely patient-related risk factors, possible hosting of several microorganisms, and variations in anti-biotherapy protocols. The French organisation of referral centres for the treatment of osseous-articular infections involves multidisciplinary teams linking specialised surgeons with bacteriologists, offering the opportunity to conduct multicentre trials. Thus, a number of infected primary or revision TKR, referred to these centres, were collected retrospectively. It was hypothesised that surgery type (one- vs. two-stage re-implantation with articulated or static spacers) would not influence cure rates and functional results.

Materials and methods

A multicentre cohort was studied: it involved six referral centres. All patients with infected TKR, requiring implant removal and subsequent re-implantation by 1 or 2 senior surgeons from each institution between 2005 and 2010, were included retrospectively. No patient was excluded because of previous infections and prior operations.

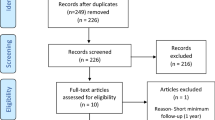

Totally, 355 patients were collected. Seventy were excluded (20 %) because of insufficient follow-up (n = 41 with less than 2-year follow-up), incomplete data (n = 20), or suboptimal protocol (inadequate bacterial detection or antibiotic therapy adaptation, n = 9), leaving a study population of 285 patients (285 knees). Fifty-four infection recurrences before 2 years gave 231 patients (231 knees) with complete 2-year clinical and radiological follow-up (Fig. 1).

All staff adhered to the same principles of microorganism identification, extensive excision of infected soft tissues, adapted and prolonged anti-biotherapy administered intravenously first, then continued orally until normalisation of biological parameters. Synergic 6-week bi-anti-biotherapy was prescribed, based as often as possible (in the absence of resistance) on the association of levofloxacin and rifampicin against Staphylococci, while amoxicillin preferentially targeted Streptococci. In all centres, implant removal was considered mandatory if infection symptoms occurred more than 3 weeks after the index operation, or after the supposed date of contamination. One-stage procedures were performed as standard care in 2 centres, whereas in the other 4 centres, two-stage re-implantation remained the gold standard, with only static spacers in 1 of them and only articulated spacers in 3 of them. Because all participating centres applied 1 protocol exclusively, there was no discussion about choice of treatment sequence, i.e., one- or two-stage procedures. This contributed to uniform indications and minimised biases due to surgeons’ subjective judgements. In practice, patients were referred to the centre closest to their home, regardless of the current institutional protocol.

Active knee flexion ranges were gauged manually at last follow-up by goniometer, and functional results were assessed as International Knee Society (IKS) scores [12].

All centres met the criteria of Laffer et al. [18] in defining prosthesis-joint infection (PJI) as persistence or recurrence of the same or unknown pathogens during or after completion of antimicrobial therapy.

Polymicrobial infections were defined, according to Steckelberg and Osmon [24], as infections by at least 2 germs identified from at least 2 cultures of joint aspirates or intra-operative tissue specimens, or isolation of 2 or more microorganisms in at least 1 intra-operative culture plus evidence of infection in joint spaces (purulence, acute inflammation, sinus tract communicating with joint space). They were classified as follows: if gram-negative bacteria were found, they were considered to be responsible for the infection. In the absence of gram-negative bacteria, the causal agent was identified as Staphylococcus aureus, if any, then as Streptococci, if any, or gram-positive bacteria other than coagulase-negative Staphylococci in the absence of the former bacteria.

According to Laffer et al. [18], early infections were defined as infections occurring within 3 months after TKR, delayed infections between 3 and 24 months and late infections beyond 1 year after TKR.

The local Institutional Review Board approved the study (Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris Nord Val de Seine, IRB 00006477).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of the study populations allowed comparisons of those who underwent one-stage or two-stage TKR. Quantitative data were reported as mean and standard deviation with comparison by Student’s t test or Wilcoxon’s signed rank test, respectively. Qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and proportions with comparison by the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test. Factors associated with infection recurrence were then identified by uni- and multi-variate logistic regression with random effect on the referral hospital (mixed model). The random effect on centre allowed modelling of existing variability between procedures and thus provided correct estimators. Associations were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) and calculated with 0.1 accuracy. Variables included in multivariate analysis were linked with infection recurrence and at least 25 % significance on univariate analysis, but non-collinear with other variables on univariate analysis. Interactions with surgery type (one-stage, two-stage articulated, two-stage static) were investigated. Sub-group analysis was conducted in case of significant interactions (p < 0.05). All tests were 2-tailed with a significance level of 5 %.

All patients were anonymised before being recorded in our database. Birth and operation dates were replaced by age and length of follow-up. Two investigators (TD and CE) performed statistical analysis with R software, 3.02 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using Modern Applied Statistics with S and glmmML packages. This observational study was reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement.

Description of study population

Of the 285 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 108 patients (108 knees) underwent one-stage exchange and 177 patients (177 knees) submitted to two-stage exchange. They were, respectively, followed for 44 ± 25 months (0–120) and 55 ± 32 months (4–120) until recurrence. Patients with less than 2-year follow-up were those with early infection recurrence. Compared to the one-stage group, two-stage patients had different median age (p = 0.003) and pre-operative skin aspect (p = 0.002) (Table 1).

In primary infected TKR, the numbers of early, delayed and late infections were not significantly different in the two groups. In both the one-stage and two-stage groups, 27 % of early infections, respectively, underwent previous debridement (Table 2). Late infections occurred on average 5 years after the index operation. In infected TKR revision, previous attempts at infection control (debridement and/or implant removal) occurred more frequently in the two-stage group (60 vs. 30 %; p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Anterior tibial tuberosity osteotomies were performed in 38 % of one-stage and 26 % of two-stage exchanges (n.s.). In the two-stage group, extensive tibial and femoral osteotomies [20] were required in 3 patients to remove infected, cemented hinge prostheses. In the two-stage group, 131 of acrylic spacers were articulated, while 46 were static. The time interval separating the 2 stages was longer in the articulated spacer subgroup (5.6 ± 7.5 vs. 3.3 ± 2.5 months, p = 0.046). A gastrocnemius flap was undertaken in 5 of the one-stage and 7 of the two-stage procedures. A vastus lateralis flap was created in a two-stage procedure.

Looking for at least 15 % difference in cure rates required 109 patients in each sample with an alpha error of 5 % and beta error of 20 % (power 80 %).

Results

Among 31 gram-negative bacteria-related infections, 1 was attributed to 2 different gram-negative strains. The identified bacteria were 12 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 7 Escherichia coli, 5 Enterobacter cloacae, 1 Proteus mirabilis, 2 Proteus vulgaris, 2 Klebsiella oxytoca, 1 Serratia marcescens, 1 Serratia liquefaciens, and 1 Morganella morganii. Thirty-seven patients (13 %) had polymicrobial infections, in which 13 involved a gram-negative bacterium (35 %).

Table 3 shows the distribution and fate of infection recurrences between the one- and two-stage groups. Most of them underwent re-revision, respectively, 29 ± 36 months (0–137) and 21 ± 26 months (0–100) from the index operation.

In univariate analysis, patient gender, age, surgery type, previous surgery, cutaneous status, body mass index (BMI), number and type of bacteria were associated with infection recurrence (Table 4). Compared to Coagulase-negative Staphylococci, risks of infection by S. aureus, a gram-negative bacterium, and other gram-positive bacteria were high. Methicillin and/or Rifampicin resistance of gram-positive bacteria was not associated with infection recurrence. Known risk factors of infection (diabetes mellitus, immuno-suppression) were not linked with infection recurrence.

Interaction between gender and type of surgery was significant. Infection recurrences were lower in the two-stage protocol with articulated spacers in men (OR 0.19 [0.05–0.69], p = 0.01).

In multivariate analysis, while linkage of two-stage TKR with articulated spacers and recurrence was not statistically significant, two-stage TKR with static spacers was independently coupled with infection recurrence (OR 4.3 [1.1–17.9], p = 0.04), as were fistulae (OR 3.4 [1.2–10.2], p = 0.03) and infection by gram-negative bacteria (OR 3.3 [1.0–10.6], p = 0.05). Because of interaction with gender, multivariate analysis was conducted separately in males and females (Table 5). In men (n = 133), surgery type was not associated with infection recurrence. Only fistulae and gram-negative bacteria significantly increased risk independently of other factors (OR 5.4 [1.1–27.4], p = 0.04 and OR 8.4 [1.2–61.9], p = 0.04, respectively). In women (n = 152), compared to the one-stage procedure, the two-stage protocol with static spacers significantly increased the risk of infection recurrence (OR 5.9 [1.5–23.6], p = 0.01). The two-stage protocol with articulated spacers also increased this risk but did not reach significance (OR 3.0 [0.9–9.8], n.s.).

Intra-operative, early and late complication rates were not different between groups (Table 6). In patients without infection recurrence, final IKS function scores were, respectively, 88.6 ± 9.4 (n = 83) and 89.7 ± 2 (n = 122) and knee scores were, respectively 74.6 ± 4.1 and 75.1 ± 1.6. Flexion gain was 14° ± 23° (−20; 110°) in the one-stage group and 11° ± 28° (−50; 100°) in the two-stage group (n.s.). Flexion range was 97° ± 18° (40–130) in the one-stage group and 91° ± 24° (10; 140°) in the two-stage group (n.s.). Patients with articulated spacers gained 12 ± 28° flexion versus 7 ± 27° in those with static spacers (n.s.). Average flexion range was 93 ± 24° in the former and 83 ± 28° in the latter (n.s.).

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was that pre-operative fistulae, infections with gram-negative bacteria and a two-stage protocol with static spacers significantly increased the risk of infection recurrence. The risk associated with static spacers was higher in women than in men. One explanation of the apparent superiority of articulated over static spacers in terms of infection recurrence may be that the friction provoked by knee flexion might increase antibiotic release in surrounding soft tissues.

Comparison of one- and two-stage procedures in the treatment of infected TKR is arduous because many variables can influence the outcome. Randomised trials are difficult to conduct because lengthy inclusion periods are necessary to obtain large enough arms and reach significance. Besides, patients may not be representative. Meta-analysis also appears to be disputable owing to the heterogeneity of studies included [14, 22]. Multicentre trials collecting patients from specialised institutions appear to be effective ways of collecting sufficient data for multivariate analysis.

In the literature, comparison remains inconclusive. In the review by Jämsen et al. [14], eradication rates were 82 % for two-stage exchanges and 73 % for one-stage exchanges. Notably, patients with less than 2-year follow-up were included, which may have overestimated the eradication rate [14]. Bauer et al. [2], in a smaller retrospective series, reported eradication rates of 84 and 87 % in two-stage versus one-stage procedures, respectively.

Cure rates with two-stage procedures are generally higher than in the present study. Haleem et al. [10] reported a 5-year eradication rate of 94 % with two-stage procedures and implant removal because of reinfection as endpoint, whereas the present work noted 69 % with reinfection revised or not as endpoint. Bauer et al. [2] came to the conclusion that spacer type does not influence the clinical results, but did not rely on multivariate analysis. Moreover, the present study included multi-operated patients, some of them implanted with extension stems and extensive cementing (28 % in each group). Such factors were identified as complicating infection management [4]. These results support the conclusion of systematic reviews [14, 22] that, while there was a trend towards delayed final re-implantation with articulated spacers, the eradication rate was improved in comparison with static spacers.

Contracting treatment to a single stage did not reduce complication numbers and types. Similarly, functional results were not improved in patients without infection recurrence. This is not in agreement with the findings of Haddad et al. [9], who, however, investigated cohorts of very select patients. In contrast, Baker et al. [1] confirmed the impression of the present study, basing themselves on patients’ reported outcome measures. They suggested that decision-making between one- and two-stage exchanges should be guided by re-infection rates. The 77 % eradication rate with one-stage exchange reported here may appear to be somewhat disappointing. Previously published papers have recorded single institutional experiences with smaller cohorts. Jenny et al. [15] encountered an 87 % survival rate at 3-year follow-up, which did not take into account late infections occurring after the third post-operative year. Buechel et al. [3] obtained long-term results with one-stage procedures in 22 patients, of whom 91 % were free of recurrent infection with average follow-up of 10 years. However, some patients with less than 2-year follow-up were included. In a large monocentric cohort with at least 5-year follow-up, von Foerster et al. [25] reported results consistent with the present data. Indeed, 76 out of 104 patients (73 %) were cured by the index operation.

Other factors, such as the rate of multi-organism infections or resistance to antibiotics, have been incriminated as failure predictors. Marculescu and Cantey [19] achieved a lower success rate in polymicrobial compared to mono-microbial infections. On the other hand, Hirakawa et al. [11] garnered 71 % success with two-stage procedures after polymicrobial-related infections. In the present study, polymicrobial infections increased the risk of recurrence, but were more frequently associated with gram-negative bacteria, which appeared to be predicators of failure in male patients. Indeed, at least 1 gram-negative bacterium was identified in 35 % (13/37) of polymicrobial infections, and the prevalence of P. aeruginosa among gram-negative bacteria identified was 39 % (12/31). Thus, the role of polymicrobial infections after TKR remains unclear. Antibiotic susceptibility may also have influenced the results. Senneville et al. [23] suggested that methicillin-resistant S. aureus was not associated with a worse outcome in PJI, but that rifampicin with quinolone was a significant predictor of success. In the present study, neither methicillin nor rifampicin resistance was linked to a higher risk of recurrence. Finally, although BMI greater than 35 was previously found to be associated with a higher risk of infection [23], statistical significance was not reached with multivariate analysis. We discerned that fistulae were an independent factor significantly decreasing the eradication rate. In contrast, Bauer et al. [2] did not identify fistulae as a recurrence factor. In practice, fistulae excision may induce significant soft tissue defects, which complicate wound closure and may require additional plastic surgery.

The present study had a number of limitations. First, it was a retrospective cohort, in which data were collected from medical charts. Because of incomplete information in the remaining patients, the staging system of McPherson et al. [21] could not be used. Second, surgical procedure allocation (one- or two-stage) was not randomised. Thus, due to cluster effects, it might have misestimated associations. However, this has been taken into account in statistical analysis, as centre identification served as a random effect. Finally, follow-up length and failure criteria remained the main obstacles to definitive conclusions. Two years are commonly accepted as representing enough follow-up before drawing conclusions about infection eradication. However, infections beyond 2 years are frequent and may precipitate different interpretations. Moreover, recurrence by another microorganism may be considered as either a new haematogenous infection or as recurrence of the same infection in which one of the involved microorganisms was not identified initially. In some early recurrences, no microorganism was identified in patients who were still on antibiotics because of previous infections. Thus, broad acceptance of all types of infections as a criterion for failure appears to be realistic.

Conclusion

Keeping these limitations in mind, the present study disclosed that pre-operative fistulae, gram-negative bacteria-related infection and two-stage procedures increased the risk of infection recurrence, especially in women if performed with static spacers. This suggests that a one-stage procedure may be more advantageous, because it offers greater comfort with the same final result. Whatever the procedure, it must be remembered that success relies primarily on the precision of surgical excision, the adequacy of anti-biotherapy and the absence of co-morbidities [16].

References

Baker P, Petheram TG, Kurtz S, Konttinen YT, Gregg P, Deehan D (2013) Patient reported outcome measures after revision of the infected TKR: comparison of single versus two-stage revision. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21:2713–2720

Bauer T, Piriou P, Lhotellier L, Leclerc P, Mamoudy P, Lortat-Jacob A (2006) Results of reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty: 107 cases. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 92:692–700

Buechel FF, Femino FP, D’Alessio J (2004) Primary exchange revision arthroplasty for infected total knee replacement: a long-term study. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 33:190–198

Cataldo MA, Petrosillo N, Cipriani M, Cauda R, Tacconelli E (2010) Prosthetic joint infection: recent developments in diagnosis and management. J Infect 61:443–448

Cui Q, Mihalko WM, Shields JS, Ries M, Saleh KJ (2007) Antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the treatment of infection associated with total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89:871–882

Durbhakula SM, Czajka J, Fuchs MD, Uhl RL (2004) Antibiotic-loaded articulating cement spacer in the 2-stage exchange of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 19:768–774

Goksan SB, Freeman MA (1992) One-stage reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 74:78–82

Goldman RT, Scuderi GR, Insall JN (1996) 2-stage reimplantation for infected total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 331:118–124

Haddad FS, Sukeik M, Alazzawi S (2015) Is single-stage revision according to a strict protocol effective in treatment of chronic knee arthroplasty infections? Clin Orthop Relat Res 473:8–14

Haleem AA, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD (2004) Mid-term to long-term followup of two-stage reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 428:35–39

Hirakawa K, Stulberg BN, Wilde AH, Bauer TW, Secic M (1998) Results of 2-stage reimplantation for infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 13:22–28

Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN (1989) Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 248:13–14

Insall JN, Thompson FM, Brause BD (2002) Brause BD Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983 65(8):1087–1098

Jamsen E, Stogiannidis I, Malmivaara A, Pajamaki J, Puolakka T, Konttinen YT (2009) Outcome of prosthesis exchange for infected knee arthroplasty: the effect of treatment approach. Acta Orthop 80:67–77

Jenny JY, Barbe B, Gaudias J, Boeri C, Argenson JN (2013) High infection control rate and function after routine one-stage exchange for chronically infected TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471:238–243

Joulie D, Girard J, Mares O, Beltrand E, Legout L, Dezeque H, Migaud H, Senneville E (2011) Factors governing the healing of Staphylococcus aureus infections following hip and knee prosthesis implantation: a retrospective study of 95 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 97:685–692

Kalore NV, Gioe TJ, Singh JA (2011) Diagnosis and management of infected total knee arthroplasty. Open Orthop J 5:86–91

Laffer RR, Graber P, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W (2006) Outcome of prosthetic knee-associated infection: evaluation of 40 consecutive episodes at a single centre. Clin Microbiol Infect 12:433–439

Marculescu CE, Cantey JR (2008) Polymicrobial prosthetic joint infections: risk factors and outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466:1397–1404

Massin P, Boyer P, Sabourin M, Jeanrot C (2012) Removal of infected cemented hinge knee prostheses using extended femoral and tibial osteotomies: six cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 98:840–844

McPherson EJ, Woodson C, Holtom P, Roidis N, Shufelt C, Patzakis M (2002) Periprosthetic total hip infection: outcomes using a staging system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 403:8–15

Romano CL, Gala L, Logoluso N, Romano D, Drago L (2012) Two-stage revision of septic knee prosthesis with articulating knee spacers yields better infection eradication rate than one-stage or two-stage revision with static spacers. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:2445–2453

Senneville E, Joulie D, Legout L, Valette M, Dezeque H, Beltrand E, Rosele B, d’Escrivan T, Loiez C, Caillaux M, Yazdanpanah Y, Maynou C, Migaud H (2011) Outcome and predictors of treatment failure in total hip/knee prosthetic joint infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 53:334–340

Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR (2000) Prosthetic joint infection. In: Bisno AL, Waldwogel FA (eds) Infections of indwelling prosthetic devices. American Society of Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp 173–209

von Foerster G, Kluber D, Kabler U (1991) Mid- to long-term results after treatment of 118 cases of periprosthetic infections after knee joint replacement using one-stage exchange surgery. Orthopade 20:244–252

Windsor RE, Insall JN, Urs WK, Miller DV, Brause BD (1990) Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. Further follow-up and refinement of indications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72:272–278

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all contributors to this work for their help in data collection and analysis: Hôpital Bichat Claude Bernard, Université-Paris Diderot (T. Rouanet, P. Massin, D. Huten); Institut Calot, Berck sur Mer (A. Cazenave); Hôpital La Croix Saint Simon, Paris (L. Lhotellier, P. Mammoudi); Université Nancy (D. Block, O. Roche, D. Mole); Hôpital Salengro, Université Lille (P. Cholevinsky, G. Pasquier, H. Migaud); Hôpitaux Universitaires, Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg (B. Barbe, J.Y. Jenny). They also thank T. Rouanet, J. Delambre, B. Brunschweiler, T. Amouyel, A. Cazenave, L. Lhotellier, D. Block, I. Klebaner, E. Felts, P. Cholevinsky, E. De Keating, S. Touchais, F. Basselot, C. Lautridou, B. Freychet and B. Barbe for patient chart reviews and reading radiographs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

PM has received royalties from Microport and Ceramconcept and is consultant to Evolutis. LL is consultant to Tornier and Amplitude and has received royalties from Amplitude. GP is consultant to Zimmer. OR is consultant to Zimmer, Depuy and Tornier. AC is consultant to Adler Ortho. JYJ is consultant to Aesculap, Depuy, FH Orthopedics, Bayer and Sanofi.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Massin, P., Delory, T., Lhotellier, L. et al. Infection recurrence factors in one- and two-stage total knee prosthesis exchanges. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 3131–3139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3884-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3884-1