Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate the incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture in Denmark from 1994 to 2013 with focus on sex, age, geographical areas, seasonal variation and choice of treatment.

Methods

The National Patient Registry was retrospectively searched to find the number of acute Achilles tendon rupture in Denmark during the time period of 1994–2013. Regional population data were retrieved from the services of Statistics Denmark.

Results

During the 20-year period, 33,160 ruptures occurred revealing a statistically significant increase in the incidence (p < 0.001, range = 26.95–31.17/100,000/year). Male-to-female ratio was 3:1 and average age 45 years for men and 44 years for women. There was a statistically significant increasing incidence for people over 50 years. A higher incidence in rural compared with urban geographical areas was found, but this was not statistically significant. There was a statistically significant decreasing incidence of patients treated with surgery from 16.9/105 in 1994 to 6.3/105 in 2013.

Conclusions

The incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture increased from 1994 to 2013 based on increasing incidence in the older population. There was no difference in incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture in the rural compared with urban geographical areas. A steady decline in surgical treatment was found over the whole period, with a noticeable decline from 2009 to 2013, possibly reflecting a rapid change in clinical practice following a range of high-quality randomized clinical trials (RCT).

Level of evidence

IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Achilles tendon rupture typically occurs among young active adults, and it is a frequent (11–37 per 100,000 per year) and potentially disabling injury [5, 12, 15]. Epidemiological studies have shown an increasing incidence, but most data are old with diverse results and lack information concerning the impact of sex, age, geographical and seasonal variation [5, 12, 15, 19].

The mean age at the time of rupture has been reported to be between 30 and 46 years [5, 10–12, 15, 21–23] with more men than women acquiring an acute Achilles tendon rupture (male-to-female ratio 2.9–5.7:1) [5, 11, 12, 15, 21–23]. A finnish study reported higher incidence rates in urban geographical areas (13.8/105) than rural geographical areas (7.6/105) [19]. Also seasonal variation seems to have an impact on the incidence of [5, 12, 22]. Several studies report the highest incidence during the spring peaking in March [19, 22, 23].

The best treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture is frequently studied and debated [2, 7–9, 13, 18]. Surgery has been the preferred treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture in most hospitals across Scandinavia over the past decade, but a range of studies have questioned the efficacy of surgery [1, 6, 17]. Mattila et al. [14] found a decreasing rate in surgery of acute Achilles tendon rupture in Finland over the last few years, indicating that merging evidence does in fact influence clinical practice.

Most epidemiological studies are limited by a selected cohort from one hospital or region [5, 11, 12, 15, 16, 19, 22]. Denmark is an optimal setting to perform a nationwide epidemiological study concerning acute Achilles tendon rupture as all patients seeking medical care in Denmark since 1977 have been registered with their social security number in the National Patient Register (Lands Patient Registeret, LPR).

Considering the demographical changes of the population and the increasing focus on sporting activities, there is a need for an updated epidemiological study of acute Achilles tendon rupture. Mainly due to an increasing elderly population, we hypothesized that the incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture has been increasing over the past 20 years.

Materials and methods

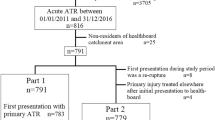

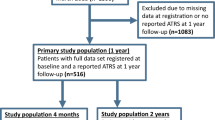

The study was conducted as a retrospective registry study. National population data were compiled by extracts from the Danish National Patient Registry and services of Statistics Denmark. In Denmark, all healthcare providers are obliged to register all inpatient and outpatient contacts, using the unique social security number, in the Danish National Patient Registry. From 1994, registration has been performed using the ICD-10 classification system; from 1996, surgical activity has been registered according to the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) Classification Of Surgical Procedures (NCSP). The register was searched from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 2013. For patients registered under the ICD-10 code for acute Achilles tendon rupture (DS860), the following information was extracted: sex, age, municipality, date of injury and surgical treatment. Due to multiple registrations (inpatient and outpatient contacts) referring to the same injury within the Danish National Patient Registry, only the first contact was included in the study. Data concerning surgical treatment were extracted from January 1, 1996, to December 31, 2013, as the NOMESCO Classification Of Surgical Procedures was introduced in 1996. The codes KNGL49, KNHL49 and KNHL19 indicated surgical treatment. There are no data available concerning validity of coding in the Danish National Patient Registry.

National population data concerning sex, age and geographical population density were retained from the services of Statistics Denmark from 1994 to 2013 (freely available at http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280) [3]. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency [4]. According to Danish legislation, no IRB approval was needed as the study is a retrospective registry study. When investigating seasonal variation, winter was defined as the months of December, January and February, and so forth. Geographical area was defined as urban for municipalities with population of at least 80,000 in 1994 (Copenhagen, Aarhus, Odense, Aalborg, Frederiksberg and Esbjerg). All others were considered rural.

The incidence rate was calculated as the number of injuries divided by the person-years of risk (PYRS). The PYRS was defined as the sum of years each person is at risk of having an accident within each year. If a person did not die within the year, they contributed a year, and if a person died at some point during that year, it was assumed that the person contributed half a year. Since exact dates were not available in the death tables, this assumption was made. From this definition, the PYRS could be calculated as the number of persons alive during the year minus half the number of persons who died during the year. The incidence was multiplied by 100,000 to give an unit of incidence per 100,000 person-years.

Modelling

The analysis was performed to investigate whether there was a change in the incidence rates stratified on sex or geographical area during 1994–2013. The operation rates were also analysed to determine change during 1996–2013.

Analysis for sex and geographical area

Analysis of the incidence change for sex and geographical area was done using Poisson regression, with PYRS used as the offset. The models (M1.1, M1.2 and M1.3) included year as a linear change, sex and geographical area and were adjusted for age (18–30, 31–50, 51–70 and 70+). All models used the quasi-Poisson distribution in order to estimate the dispersion parameter (all found to be between 1.21 and 2.74) used to evaluate the models.

In the first model (M1.1), no interaction was used and this model estimated the change per year; in the second model (M1.2), the year–sex and year–area interactions were introduced in two separate models. These models gave estimates of the change per year for the sexes and geographical areas.

The third model (M1.3) evaluated all possible interactions between the variables using backwards stepwise regression with the Chi-square test, resulting in a model with year–age, area–age, year–area, sex–age and sex–year interactions as well as a three-way interaction between year, age and sex. Since we want to investigate the effect of the year with regard to sex and geographical area corresponding to the effect of the year–sex and year–area interactions, these were not tested.

Analysis of treatment choice

For surgery, the change in the ratio of injuries resulting in surgery was evaluated. Since the surgery date is not studied but only if surgery occurs, the set-up differs from the previous models, logistic regression was used with yes/no to surgery as outcome. The models (M2.1, M2.2) included year and were adjusted for age and sex. It is important to note that year refers to the year of the injury and not year of surgery. From plots of the change in ratio between surgery and nonsurgery over years, it was clear that the change was not linear. A drop in surgery seemed to be present around 2010. Therefore, year was included as a natural cubic spline with knots chosen at 2002, 2006 and 2010; other years were chosen for equal spacing of knots. Again, an initial model (M2.1) was used with no interaction of year, as well as a second model (M2.2) where again all interactions were evaluated using backwards stepwise regression with the Chi-square test. Here age–sex and age–year interactions were present.

Statistical analysis

Results were considered statistically significant at p value <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 33,160 acute Achilles tendon ruptures were registered during the 20-year period from January 1994 to December 2013. We included 75.2 % men (n = 24,939) and 24.8 % women (n = 8221), resulting in a male-to-female ratio of 3:1. We found a statistically significant increase in incidence from 26.95/105/year in 1994 to 31.17/105/year in 2013 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). When analysing the results by age and sex, we found a statistically significant increasing incidence in patients over 50 years for both sexes. In the group of 31–50-year olds, a statistically nonsignificant change was found also for both sexes and in the group of 18–30-year olds a statistically significant decrease in incidence was found again for both sexes (Table 1; Figs. 2, 3). The mean incidence for women was 15.2/105/person-year and for men 46.9/105/person-year (Table 1). The median age for men was 42 years (range 6–84) in 1994 and 49 years (range 6–98) in 2013. For women, the median age was 42 years (range 2–93) in 1994 and 48 years (range 7–93) in 2013. Age-adjusted incidence for both genders peaked at the age of 41 showing a mean incidence of 68.6/105/person-year.

The seasonal variation over the period showed a higher incidence during the fall with peak incidence in September and lowest incidence in July (Fig. 4). The lowest incidence was found during summer followed by spring. Comparison of the mean incidence between rural and urban geographical areas showed a mean incidence of 31.4/105/year in rural areas and mean incidence of 29.4/105/year in urban areas (Fig. 5). There was a statistically nonsignificant increase in incidence over time in rural compared to urban geographical areas of 0.1 % per year (ns) and a statistically nonsignificant difference in the incidence intercept between urban and rural geographical areas of 2.8 % (ns).

The mean incidence for surgical treatment was 14.9/105 in the period with a statistically significant decrease in incidence from 16.9/105 in 1994 to 6.3/105 in 2013 (Fig. 1). The incidence for men was 26.9/105 in 1994 and 9.9/105 in 2013, and for women 7.3/105 in 1994 and 2.7/105 in 2013 with no statistically significant difference in the probability of operation between the genders (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture with focus on sex, age, geographical area, seasonal variation and choice of treatment. The most important finding was a statistically significant increase in incidence from 1994 to 2013 (p < 0.001) due to an increase in the group of patients above 50 years of age for both men and women (p < 0.001). In the group of 30–50-year olds, there was no increase in incidence and in the group of 18–30-year olds a statistically significant decline in incidence was observed for both genders (p < 0.001). Lantto et al. [10] reported an increasing incidence for all age groups, but the study was limited by selection bias as only one region in Finland was studied. In Sweden, a declining incidence for younger men was reported [6]. This is the first study to report a statistically significant decrease for younger men as well as women.

Median age increased by 6 years for women and 7 years for men during the study period, and is consistent with the increased incidence in the older age groups. This finding is supported by a previous study [6] and might be due to a larger and more active older generation.

The median age for men was 45 and 44 years for women at time of acute Achilles tendon rupture, which corresponds to findings of earlier studies [5, 12, 19, 23]. The male-to-female ratio was 3:1, which in comparison with the finding of Moller et al. and Nillius et al. [15, 16] seems rather low. It does, however, fit well with the pooled average male-to-female ratio of previous incidence studies as reported by Vosseller et al. [25]. A lower male-to-female ratio might be explained by a higher degree of gender equality, leading to a higher incidence of sporting activity amongst the female population. It is still unknown why more men than women gain acute Achilles tendon rupture. Hormonal and biological factors have been suggested to be involved and are a field of future investigation [25].

No statistically significant difference in incidence was found comparing rural and urban geographical areas, and no statistically significant change over time was found (Fig. 5). An active lifestyle can be found in both areas, and geographical setting does not seem to have an impact as suggested by Nyyssönen et al. [19]. In this study, urban geographical areas were defined as cities with more than 80,000 citizens. A different definition might have led to a different result.

The highest incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture was observed during the fall with a peak incidence in September. This diverged from previous studies where the highest incidence has been reported during the spring peaking in March [19, 22, 23]. A possible explanation could be the launch of all major sports after the summer holidays.

Incidence of surgical treatment showed a remarkable drop from 2009 to 2013 (Fig. 1), reducing the probability of surgery by half for most age groups (Fig. 6). In 2013, the probability of surgical treatment declined steadily with age from 40 % in the group of 18–30 year of age to 3 % for people above 70 years of age (Fig. 6). Surgery has been the preferred treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture in most hospitals across Scandinavia over the past decade [1, 6, 17], but recent studies [6, 14] indicate a swift decline in incidence of surgery. These finding might reflect a rapid change in clinical practice following a range of high-quality randomized clinical trials (RCT) [18, 20, 24, 26].

This is a nationwide retrospective registry study including the whole population of Denmark, thereby minimizing the risk of selection and confounding bias. The risk of information bias persists as patients can have been incorrectly diagnosed or registered. This risk of incorrect diagnose is minimal as diagnosis of acute Achilles tendon rupture is an easy clinical diagnose. Also the risk of incorrect registration is considered minimal as medical care is free of charge in Denmark and all patients with an acute Achilles tendon rupture are expected to seek medical care and therefore get registered in LPR. Both private and public hospitals depend on correct registration to get reimbursement.

It is a limitation of the study that we were unable to determine whether multiple diagnoses on the same person were due to readmission with the same rupture, a re-rupture or a new rupture on the contralateral leg.

Data concerning surgical treatment did not include date of surgery. As such, it was not possible to distinguish primary operations from secondary operations due to complications after an initially conservative treatment. This might provide a higher incidence of surgical treatment than the actual value and the decrease in surgical treatment might be underestimated.

This study has a high degree of clinical relevance as it documents a rapid change in clinical practice with a more than 50 % decline in surgical treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture. Such a rapid change in clinical practice should lead to reflection amongst clinicians and is important for politicians when planning healthcare resources. Furthermore, the increase in incidence of acute Achilles tendon ruptures for people above 50 does raise the question whether preventive measures should be applied.

Conclusions

The incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture has increased from 1994 to 2013 as a result of increasing incidence in the older population. There was no difference in incidence in rural geographical areas compared to urban geographical areas, and a higher incidence was reported during the fall with a peak in September. A steady decline in surgical treatment was found over the whole period, with a noticeable decline from 2009 to 2013, possibly reflecting a rapid change in clinical practice following a range of high-quality RCTs.

References

Barfod KW, Nielsen F, Helander KN, Mattila VM, Tingby O, Boesen A, Troelsen A (2013) Treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture in Scandinavia does not adhere to evidence-based guidelines: a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study of 138 departments. J Foot Ankle Surg 52(5):629–633

Cetti R, Christensen SE, Ejsted R, Jensen NM, Jorgensen U (1993) Operative versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture a prospective randomized study and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med 21:791–799

Danmarks Statistik (2014) Statistikbanken-Danmarks Statistik. http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.a. Accessed 01 Oct 2014

Datatilsynet (2014) Datatilsynet: introduction to the Danish data protection agency. http://www.datatilsynet.dk/english/. Accessed 01 Oct 2014

Houshian S, Tscherning T, Riegels-Nielsen P (1998) The epidemiology of Achilles tendon rupture in a Danish county. Injury 29:651–654

Huttunen TT, Kannus P, Rolf C, Felländer-Tsai L, Mattila VM (2014) Acute Achilles tendon ruptures: incidence of injury and surgery in Sweden between 2001 and 2012. Am J Sports Med 42:2419–2423

Jiang N, Wang B, Chen A, Dong F, Yu B (2012) Operative versus nonoperative treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis based on current evidence. Int Orthop 36:765–773

Keating JF, Will EM (2011) Operative versus non-operative treatment of acute rupture of tendo Achilles: a prospective randomised evaluation of functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93:1071–1078

Kocher MS, Bishop J, Marshall R, Briggs KK, Hawkins RJ (2002) Operative versus nonoperative management of acute Achilles tendon rupture: expected-value decision analysis. Am J Sports Med 30:783–790

LanttoI Heikkinen J, Flinkkilä T, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J (2014) Epidemiology of Achilles tendon ruptures: increasing incidence over a 33-year period. Scand J Med Sci. doi:10.1111/sms.12253

Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S (1996) Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop 67:277–279

Levi N (1997) The incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Copenhagen. Injury 28:311–313

Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, Lim KP, Bleakney R (2003) Early weightbearing and ankle mobilization after open repair of acute midsubstance tears of the Achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med 31:692–700

Mattila VM, Huttunen TT, Haapasalo H, Sillanpää P, Malmivaara A, Pihlajamäki H (2013) Declining incidence of surgery for Achilles tendon rupture follows publication of major RCTs: evidence-influenced change evident using the Finnish registry study. Br J Sports Med. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092756

Moller A, Westlin NE (1996) Increasing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 67:479–481

Nillius AS, Nilsson BE, Westlin NE (1976) The incidence of Achilles tendon. Acta Orthop Scand 47:118–121

Nilsson Helander K, Olsson N, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (2014) Individualiserad behandling viktig vid akut hälseneruptur. Lakartidningen 111:CXWT

Nilsson-Helander K, Silbernagel KG, Thomeé R, Faxén E, Olsson N, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (2010) Acute Achilles tendon rupture: a randomized, controlled study comparing surgical and nonsurgical treatments using validated outcome measures. Am J Sports Med 38:2186–2193

Nyyssönen T, Lüthje P, Kröger H (2008) The increasing incidence and difference in sex distribution of Achilles tendon rupture in Finland in 1987–1999. Scand J Surg 97:272–275

Olsson N, Silbernagel KG, Eriksson BI, Sansone M, Brorsson A, Nilsson-Helander K, Karlsson J (2013) Stable surgical repair with accelerated rehabilitation versus nonsurgical treatment for acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a randomized controlled study. Am J Sports Med 41:2867–2876

Raikin SM, Garras DN, Krapchev PV (2013) Achilles tendon injuries in a United States population. Foot Ankle Int 34:475–480

Scott A, Grewal N, Guy P (2014) The seasonal variation of Achilles tendon ruptures in Vancouver, Canada: a retrospective study. BMJ Open. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004320

Suchak AA, Bostick G, Reid D, Blitz S, Jomha N (2005) The incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in Edmonton, Canada. Foot Ankle Int 26:932–936

Twaddle BC, Poon P (2007) Early motion for Achilles tendon ruptures: is surgery important?: a randomized prospective study. Am J Sports Med 35:2033–2038

Vosseller JT, Ellis SJ, Levine DS, Kennedy JG, Elliott AJ, Deland JT, Roberts MM, O’Malley MJ (2013) Achilles tendon rupture in women. Foot Ankle Int 34:49–53

Willits K, Amendola A, Bryant D, Mohtadi NG, Giffin JR, Fowler P, Kean CO, Kirkley A (2010) Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a multicenter randomized trial using accelerated functional rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:2767–2775

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ganestam, A., Kallemose, T., Troelsen, A. et al. Increasing incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture and a noticeable decline in surgical treatment from 1994 to 2013. A nationwide registry study of 33,160 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24, 3730–3737 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3544-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3544-5