Abstract

Purpose

The literature data on patellar height following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) are scarce.

Methods

A total of 41 knee joints in 37 patients after UKA were prospectively evaluated for patellar height by using the Insall–Salvati and modified Insall–Salvati ratio. Patellar height was measured preoperatively, postoperatively, at 6, 12 weeks, and, at 1 year postoperatively. Patients were categorized according to age, gender, operated side, and rehabilitation program.

Results

Regarding all the patients, the Insall–Salvati ratio demonstrated a significant decrease only for the time period “postoperatively–1 year postoperatively”, whereas the modified Insall–Salvati ratio showed a significant decrease only for the period “preoperatively–postoperatively”. The Insall–Salvati ratio showed a significant decrease in the patellar height of men and left knees, whereas the modified Insall–Salvati ratio revealed a significant decrease in patients older than 65 years and those who followed a specific rehabilitation program.

Conclusions

The decrease in the patellar height after UKA occurs within the first postoperative year. Women, right knees, patients younger than 65 years and those who do not follow a specific rehabilitation program are less prone to decrease in the patellar height; ratio-specific differences are evident for each subgroup.

Level of evidence

Diagnostic study, Level III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent reports, failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) was associated with progression of the arthritis, prosthesis design, and surgical technique [3, 12]. General progression of osteoarthritis (in both, opposite knee compartment and patellofemoral joint), as a cause of failure, is estimated to occur at about 33% at a 10-year follow-up [12, 25]; these rates vary strongly for the patellofemoral joint from 10 to 67% at 10–11-year follow-up [3, 19]. Progressive osteoarthritis of the femoropatellar joint is rather rare after medial UKA as compared to that of the lateral compartment because of the overcorrection of a pre-existing varus deformity. However, alterations in the patellar biomechanics might limit the functional outcome, and hence the daily activity of the patient, even if they do not directly lead to revision surgery.

Besides the axial patellar position, the patellar position in the sagittal plane might also limit the outcome. Patella infera has been described after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [1, 5, 6, 11, 15], high tibial osteotomy [7, 17, 20, 23], and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [21]. Patella infera after TKA is associated with a limited range of movement [24]. Calculations show that 1 mm shortening of the patellar tendon would be expected to cause a loss of flexion by about 1° [24]. In a geometrical knee model, it has been demonstrated that when there is a short patellar tendon, the patella contacts the femur at a smaller angle of flexion than that when the tendon is of normal length [22].

Although patellar height changes are well described after TKA [1, 5, 6, 11, 15], literature data on the patellar position after UKA are scarce. Hence, the purpose of this prospective cohort study was to determine the patellar height after UKA and evaluate side-, gender-, age- and postoperative treatment-dependent differences.

Materials and methods

Between 2002 and 2005, a prospective cohort study was performed for the measurement of the patellar height after UKA. All operations were carried out for unilateral tibiofemoral osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence stadium III–IV). Patients were only included in the study if they had unicompartmental medial or lateral femorotibial arthritis with intact patellofemoral and contralateral femorotibial joints. The exclusion criteria included patella fracture, patellar tendon injury or insufficiency, quadriceps injury or insufficiency, and surgeries prior to prosthesis implantation that might have altered the patellar biomechanics (lateral release and high tibial osteotomy). Patients having an intraoperative lateral release or removal of patellar osteophytes were also excluded from the study. Intraoperatively diagnosed laxity or insufficiency of the anterior or posterior cruciate ligament also led to exclusion from the study.

Of the 67 patients operated during this time period, 30 patients were excluded because of the aforementioned criteria. A total of 41 prostheses in 37 patients were evaluated. There were 18 men and 19 women. The median age of these 37 patients was 65 (55–79) years at the time of surgery. In all the cases, Miller–Galante prostheses (Fa. Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana, USA) were implanted. All the procedures were done through a medial parapatellar approach that included patellar eversion; none were done using a minimally invasive approach. Parts of the Hoffa’s pad were resected whenever necessary. The medial compartment was replaced in 39 knees and the lateral compartment in two knees. In 21 cases, UKA was carried out in the left knees and in 20 cases in the right knees.

Postoperative care was identical for all the patients. All the patients were allowed to weight-bear on the operated leg as tolerated. At dismissal, usually 2 weeks after the surgery, knee flexion was at least 90°. The patients who wished to were transferred to an inpatient rehabilitation program for another 3–4 weeks. Those who did not wish to be transferred were advised to do ambulatory physical therapy for the same time period.

The inpatient rehabilitation program following UKA usually consists of several exercises and training programs such as physical therapy and hydrotherapy that take place throughout the day, either as a single person or in a group. On the other hand, the ambulatory physical therapy takes place 2–3 times (20–30 min each time) per week, where the physiotherapist treats only one patient at a time. In 24 cases, the inpatient rehabilitation program was followed, whereas in the remaining 17 cases, the patients performed ambulatory physical therapy.

Radiographic assessment

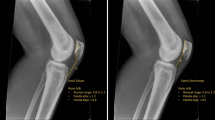

The patellar height was determined on lateral radiographs with a knee flexion angle of 20°. The patellar height was measured using the Insall–Salvati [9] (Fig. 1) and the modified Insall–Salvati ratio [8] (Fig. 2). Since it can be difficult to define exactly the point of origin and insertion of the tendon, all the radiographs for each patient were reviewed simultaneously by the first two authors. Radiographic assessment was performed using a ruler with a measurement accuracy of 1 mm. The radiographs were taken preoperatively, postoperatively (within 7 days after the surgery), at 6 weeks, 3 months, and at 1 year after the surgery.

All the patients were categorized into groups according to gender (men vs. women), age (>65 years vs. <65 years), side of the operated knee joint (left vs. right), and rehabilitation program (inpatient rehabilitation program vs. ambulatory physical therapy). The Insall–Salvati- and modified Insall–Salvati ratio were compared among these groups for each time period separately and in between the defined time periods.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 12.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). For the evaluation of the whole collective as well as subgroups for a particular time period, ANOVA analysis and post hoc test were carried out. For the comparison between the groups, a t test for unmatched pairs was performed after confirming the normal values of distribution by using the Levene’s test. Statistical significance was defined at a P value of <0.05.

Results

Insall–Salvati ratio

The Insall–Salvati ratio classified preoperatively 38 patellae as normal, two as infera, and one as alta [median value 0.93 (0.71–1.32)] (Table 1).

Evaluation of all the patients by using the Insall–Salvati ratio demonstrated a significant decrease in the patellar height only for the time period “postoperatively–1 year postoperatively” (P = 0.042).

When comparing the two gender groups alone, men demonstrated significant decreases for the time periods “postoperatively–1 year postoperatively” (P = 0.004), and “6 weeks postoperatively–1 year postoperatively” (P = 0.008). Women showed no significant changes at any time period. Comparison between genders showed no significant differences.

Comparison of the patients according to their age showed no significant decreases at any time period for both between as well as within the groups.

Regarding the operated side, no differences were seen between the groups. When the operated side was tested alone, the Insall–Salvati ratio yielded no significant differences in the patellar height of the right knees at any time period. For the left knees, significant decrease was observed only for the time period “postoperatively–1 year postoperatively” (P = 0.007).

Regarding the specific rehabilitation program after dismissal from the clinic, no significant decrease was observed at any time period for both between and within the groups.

Modified Insall–Salvati ratio

The modified Insall–Salvati classified preoperatively 37 patellae as normal and four as alta [median value 1.75 (1.35–2.63)] (Table 1).

Regarding all the patients, the modified Insall–Salvati ratio demonstrated a significant decrease only for the time period “preoperatively–postoperatively” (P = 0.019).

Regarding the gender, no significant decrease was observed at any time period for both between and within the groups.

Comparison of the patients regarding their age showed a significant decrease for the time period “postoperatively–6 weeks postoperatively” (P = 0.042) between the groups for the older group. Within each group, no significant changes could be demonstrated at any time period.

Regarding the operated side, no significant decreases could be observed at any time period for both between and within the groups.

Regarding the patients who underwent the rehabilitation program or did the ambulatory physical therapy, the modified Insall–Salvati ratio showed a significant decrease in the patellar height for the time period “postoperatively–1 year postoperatively” between both groups. Within each group, no significant changes were observed.

Discussion

The most important findings of the present study were that female patients, right knees, and patients younger than 65 years and those doing ambulatory physical therapy were less prone to decrease in the patellar height than male patients, left knees, and patients older than 65 years and those doing the inpatient rehabilitation program.

The exact etiology of the patellar height decrease after different surgical procedures is still unknown. Its cause has been ascribed to biological adaptation of the extensor mechanism, shrinkage of scar tissue, scarring, formation of a new bone, immobilization, patellofemoral fibrosis, intra-articular fibrous bands, ischemia, and trauma to the patellar tendon [24]. After TKA, some authors have suggested that the eversion of the patella leads to ischemia and trauma to the tendon, and hence, to a postoperative patella infera [24]. Fern et al. [5] and Aglietti et al. [1] reported that patients with patella infera suffer from impingement pain, whereas Figgie et al. [6] found in a similar study that such patients had both pain and restriction in the movement of the knee. On the other hand, Koshino et al. [11] reported that patella infera after TKA has no influence on the range of movement or power of the quadriceps muscle.

Not every method is suitable for the measurement of the patellar height. The Insall–Salvati ratio may be affected by the changes in the patellar morphology. Resection of patellar osteophytes at the time of resurfacing may alter the shape in the sagittal plane, thus, rendering the measurement of the Insall–Salvati ratio unreliable. Hence, all patients having intraoperative removal of patellar osteophytes were excluded from the present study. Only these two methods were chosen for the determination of the patellar height because they are independent of joint surfaces. Other ratios, such as the Blackpurne–Peel ratio [4] are affected by the position of the joint line, because they require precise identification of the proximal joint surface of the tibia for their assessment and therefore do not accurately correlate with the true patellar height after UKA.

Furthermore, interobserver variation also plays a role in the assessment of patellar height. Berg et al. [2] showed that among three observers the Blackburne–Peel method was relatively reproducible. Seil et al. [18] demonstrated for this ratio the lowest interobserver variability in a study with symptomatic knees. After TKA, Rogers et al. [16] found out that the interobserver difference was reduced using both Caton–Deschamps and the Blackburne–Peel methods as compared to the Insall–Salvati and the modified Insall–Salvati ratio. Hence, to avoid such problems, all the radiographs were reviewed simultaneously by the first two authors.

To our knowledge, there exist only two studies that tried to determine the patellar height after UKA [14, 24]. Weale et al. [24] determined the patellar height after TKA or UKA as a part of a randomized, controlled study with 84 patients. The authors defined patella infera as a decrease in 10% or more in the length of the tendon. This study demonstrated no significant changes in the patellar height at 8 months and 5 years after the surgery. Interestingly, lengthening of the tendon by 10% or more was identified in approximately 14% of their patients; however, the authors did not provide any explanation for this observation. Naal et al. [14] measured the patellar height before and after UKA by using the Blackburne–Peel and Insall–Salvati ratio and investigated the impact of patellar height on clinical outcomes 2 years after the surgery. The Blackburne–Peel values were significantly decreased after the surgery, whereas the Insall–Salvati values were not. The lower preoperative Blackburne–Peel values were negatively correlated with postoperative knee extension, whereas higher preoperative values were negatively correlated with postoperative Knee Society score. On the other hand, the lower preoperative Insall–Salvati values were negatively correlated with postoperative Knee Society score.

The present work has some differences as compared to the aforementioned studies. Weale et al. [24] did not determine patellar height according to an established method but only defined a decrease in 10% or more in the length of the tendon as a patella infera. It could be possible that if they had used the Insall–Salvati, modified Insall–Salvati or Blackburne–Peel ratio, other values could have been measured. Naal et al. observed significant differences for the Blackburne–Peel ratio; however, the Blackburne–Peel ratio is affected by the position of the joint line and this cannot always be easily identified after UKA or TKA. However, it is unclear why they could not observe any significant differences for the Insall–Salvati ratio as in the present study.

According to the modified Insall–Salvati ratio, it could be shown that a decrease in the patellar height occurs mostly during the first 6 postoperative weeks, whereas the Insall–Salvati ratio demonstrated a decrease during the first postoperative year. This is probably due to the surgical trauma to the patellar tendon and the pain-associated weakness of the quadriceps muscle that cannot act to prevent the decrease in patellar height, which might prolong over longer periods. Therefore, specific training of this muscle should be the aim of the physical therapy in order to avoid complaints in the patellofemoral joint. In contrast, it could be shown that patients who underwent a specific rehabilitation program did not benefit in comparison to those who did not follow such a program with regard to the patellar height. Probably, during such a rehabilitation program, attention is not only paid to the patellofemoral joint, but also to the range of motion of the knee joint. Perhaps, patients who have a higher risk for patellar problems should follow a more intensive postoperative training, and rather focus on strengthening the quadriceps muscle than a general rehabilitation program.

Moreover, the present study indicates that women and right knees are less likely to have a decrease in the patellar height as compared to men and left knees according to the Insall–Salvati ratio. No certain explanation can be given for this difference between the genders, especially since Koskinen et al. [12] showed no significant differences in the evaluation of revisions after UKA between male and female patients. Regarding the operated side, it could be assumed that similar to the upper extremities where most people have a stronger right side, similar strength proportions might also be present in the lower extremities. Hence, a stronger preoperative right quadriceps muscle would easily tolerate the surgical trauma as compared to a weaker muscle on the left side, and a decrease in the patellar height would rather be expected in the latter group.

In a study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register, younger patients (<65 years of age) were found to have a 1.5-fold increased risk of revision after UKA as compared to patients older than 65 years [12]. However, the exact causes of revision were not specified. Younger patients are usually more active and place more demand on their prostheses. Therefore, it could be rather expected that polyethylene damage or progression of arthritis to other joint compartments would be a more likely cause of revision as compared to problems in the patellofemoral joint. The present study demonstrated that younger patients were less likely to have a decreased patellar height according to the modified Insall–Salvati ratio. The reason could be the better elasticity of the soft-tissues or the fact that they are more active in their daily activities, which leads to a faster rehabilitation.

A recent study by Lemon et al. [13] demonstrated that excision of the infrapatellar fat pad leads to a significant shortening of the patellar tendon after TKA as compared to the knees where the fat pad is preserved. It has been shown that complete infrapatellar fat pad excision can devascularize the patella by interrupting the infrapatellar anastomosis [10] and this might be the cause for that. In our study, the possible influence of the excision of the infrapatellar pad on the patellar height was not examined; however, it might be possible that even in cases after UKA this factor could influence the patellar height.

Certainly, the present study has some limitations. The exclusion criteria were relatively strict, so only a small number of knees were included in the study. Moreover, all the patients were operated using the traditional medial parapatellar approach with patellar eversion; therefore, it cannot be surely stated how these values might be in the case of other surgical approaches. Furthermore, the mechanical axis and tibial slope were not determined, the two parameters that might have had an influence on the patellar height.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that patellar height decrease after UKA is less frequent if the patient is women, younger than 65 years, and the right knee has been operated. A more quadriceps-specific postoperative rehabilitation program might help in the prevention of a patella infera. Orthopedic surgeons should be aware of possible factors that might lead to patellar complaints, and hence, limit the functional outcome after UKA.

References

Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Gaudenzi A (1988) Patello-femoral functional results and complications with the posterior-stabilised total condylar knee prosthesis. J Arthroplasty 3:17–25

Berg EE, Mason SL, Lucas MJ (1996) Patellar height ratios: a comparison of four measurements methods. Am J Sports Med 24:218–221

Berger RA, Meneghini M, Sheinkop MB, Della Valle CJ, Jacobs JJ, Rosenberg AG, Galante JO (2004) The progression of patellofemoral arthrosis after medial unicompartmental replacement. Results at 11 to 15 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 428:92–99

Blackburne JS, Peel TE (1977) A new method of measuring patellar height. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 59-B:241–242

Fern ED, Winson IG, Getty CJM (1992) Anterior knee pain in rheumatoid patients after total knee replacement: possible selection criteria for patellar resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 74-B:745–748

Figgie HE III, Goldberg VM, Heiple KG, Moller HS III, Gordon NH (1986) The influence of tibial-patellofemoral location on function of the knee in patients with the posterior-stabilised condylar knee prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 68-A:1035–1040

Gasbeek RD, Nicolaas L, Rijnberg WV, van Loon CJ, van Kampen A (2010) Correction accuracy and collateral laxity in open versus closed wedge high tibial osteotomy. A one-year randomised controlled study. Int Orthop 34:201–207

Grelsamer RP, Meadows S (1992) The modified Insall–Salvati-ratio for patellar height. Clin Orthop Relat Res 282:170–176

Insall J, Salvati E (1971) Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology 101:101–104

Kayler DE, Lyttle D (1988) Surgical interruption of the patellar blood supply by total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 229:221–227

Koshino T, Ejima M, Okamoto R, Orii T (1990) Gradual lowriding of the patella during postoperative course after total knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Arthroplasty 5:323–327

Koskinen E, Paavolainen P, Eskelinen A, Pulkinnen P, Remes V (2007) Unicondylar knee replacement for primary osteoarthritis. A prospective follow-up study of 1,819 patients from the finnish arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop 78:128–135

Lemon M, Packham I, Narang K, Craig DM (2007) Patellar tendon length after knee arthroplasty with and without preservation of the infrapatellar fat pad. J Arthroplasty 22:574–580

Naal FD, Neuerburg C, von Knoch F, Salzmann GM, Kriner M, Munzinger U (2009) Patellar height before and after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: association with early clinical outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129:541–547

Nelissen RG, Weidenheim L, Mikhail WE (1995) The influence of the position of the pattelar component on tracking in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 19:224–228

Rogers BA, Thornton-Bott P, Cannon SR, Briggs TW (2006) Interobserver variation in the measurement of patellar height after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 88-B:484–488

Scuderi GR, Windsor RE, Insall JN (1989) Obsevations on patellar height after proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 71-A:245–248

Seil R, Müller B, Georg T, Kohn D, Rupp S (2000) Reliability and interobserver variability in radiological patellar height ratios. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:231–236

Squire MW, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Johnston RC (1999) Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. A minimum 15 year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 367:61–72

Tigani D, Ferrari D, Trentani P, Barbanti-Brodano G, Trentani F (2001) Patellar height after high tibial osteotomy. Int Orthop 24:331–334

Tria AJ Jr, Alicea JA, Cody RP (1994) Patella baja in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 299:229–234

Van Eijden TM, Kouwenhoven E, Weijs WA (1987) Mechanics of the patellar articulation: effects of patellar ligament length studied with a mathematical model. Acta Orthop Scand 58:560–566

Van Raaij TM, de Waal Malefijt J (2006) Anterior opening wedge osteotomy of the proximal tibia for anterior knee pain in idiopathic hyperextension knees. Int Orthop 30:248–252

Weale AE, Murray DW, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE (1999) The length of the patellar tendon after unicompartmental and total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 81-B:790–795

Weale AE, Murray DW, Baines J, Newman JH (2000) Radiological changes five years after unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 82-B:996–1000

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anagnostakos, K., Lorbach, O. & Kohn, D. Patella baja after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20, 1456–1462 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-011-1689-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-011-1689-4