Abstract

The stiffened plates are of demonstrable advantages and potential in offering high resistance to such extreme loading scenarios as blast. Since the distribution of the stiffeners has considerable effect on their performance, its design signifies an important topic of research. However, existing research has mainly focused on empirical design, and the configurations were largely experience based, which limits structural explosion-proof capacity. In order to improve the performance of stiffened plates against blast loading, we introduced here two new structural configurations of stiffened plates. In this study, the modified ant colony optimization (MACO) algorithm which introduces the mass constraint factor to the pheromone update function and integrates the idea of crossover and mutation was used to design the subjected to given working conditions. Specifically, material distribution of stiffeners is taken to be the design variables, and minimization of the maximum deflection of the center point of the plate to be the design objective under predetermined mass constraints. Compared with the baseline structure, the optimal designs largely improved the explosion-proof performance through distributing stiffener topology on the plates. The results showed that the optimum designs all present the reinforcement stiffeners to link with the fixed boundaries against the deformation. Moreover, the optimum designs placed more reinforcement materials in the central regions instead of four angles, and with the increase of the mass fraction, the reinforcement placement gradually extends from the center to the edges. The proposed method and new topological configurations are expected to provide some insights into design for novel protective structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Explosions caused by accidents and terrorist attacks are becoming increasing concern seriously nowadays. In order to protect the personnel and facilities from explosive damage, research on blast-resistant structures is of vital importance. As a class of effective protective structures, stiffened plates have been widely used in civil and military applications, such as hull, offshore structures, box girder, oil and gas storage tanks, and other structures. Compared with a flat shield, the plate with stiffener reinforcements is considered more effective in improving load bearing capacity with limited increase in weight, leading to a higher structural efficiency.

In order to achieve better explosion-proof performance, stiffened plates have drawn growing attention in the recent years (Kumar et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2017; Ning et al. 2006; Zheng et al. 2016). For example, Louca et al. (1998) systematically investigated the responses of stiffened and unstiffened plates under blast loading. Rudrapatna et al. (2000) studied a series of stiffened plates to predict the deformation and failure modes of these stiffened plates subjected to blast loading. Chung Kim Yuen and Nurick (2005) and Langdon et al. (2005) explored five different quadrangular plates under uniform and localized blast loading; and further analyzed the effects of stiffener configuration on the blast resistance. Goel et al. (2015) studied 11 different stiffened sandwich panels and also analyzed the effects of stiffener configuration on the explosion-proof performance. Furqan et al. (2017) investigated the stiffened panels under blast loading in terms of the explosion distance and explosion magnitude for different configurations of stiffener and curvatures of the panel.

The aforementioned studies on explosion-proof performance of stiffened structures were mainly concentrated on some specifically given stiffener configurations obtained from experience, and the topologies considered were relatively simple. A critical issue remained to be answered is whether or not there is any other more sophisticated structural configuration that may be of higher explosion-proof performance. In other words, how to place stiffener topology for achieving better explosion-proof outcome is still a rather demanding issue for designers.

Unlike the stiffened plates with linear elastic conditions, blast loading involves strong nonlinearity and transient dynamics, which introduces significant challenge for topology optimization. Limited studies were reported in literature to date (Fang et al. 2016). For example, Goetz et al. (2012) adopted hybrid cellular automaton (HCA) method for optimizing two-material distribution for maximizing energy attenuation for the plate armor. Sheyka et al. (2012) optimized microstructure and thickness of a two-layer blast-resistant composite plate by minimizing the weight and stress-to-strength ratio using multiobjective genetic topological optimization. Meng et al. (2016b) developed a new airtight blast door using topology/shape optimization. In a similar class of optimization problems involving impact loads, recently, Fang and coworkers (Fang et al. 2017; Sun et al. 2017) recently adopted heuristic optimization algorithms to design the multicell topology under single/multiple crash loading. Sun et al. (2018) proposed multicriteria decision making method, namely COPRAS (complex proportional assessment), to rank the energy absorption characteristics for optimizing the topological configuration of foam-filled multicell structures.

Further, material distribution and thickness of stiffeners may be of a distinctive effect on the explosion-proof performance. In view of the fact that most of the past studies were based upon some predefined layouts of stiffeners, it is rather restrictive of optimizing the material distribution of stiffeners and obtaining the most efficient patterns, systematically. To tackle this problem, the ant colony optimization (ACO) algorithm is proposed to explore the possible design candidates and excavate the maximum potential of the proposed stiffener patterns. Ant colony algorithm was inspired by the food hunting behavior of ant colony that has demonstrated excellent performance on discrete combination problems (Chandra Mohan and Baskaran 2012; Demirel and Toksarı 2006; Dorigo and Gambardella 1997; Liao and Su 2017; Maniezzo and Colorni 1999). For example, Solimanpur et al. (2004) solved the intercell layout design using the ACO and demonstrated that the ACO is fairly suitable for solving such a problem. Hani et al. (2007) proposed a hybrid ACO approach by coupling with a guided local search (ACO_GLS) to solving the industrial layout problems, which comes from a train maintenance facility. With the ACO_GLS method, the performance was largely improved for the optimized layout. Ding et al. (2012) presented a novel ACO algorithm for solving the vehicle routing problem, and showed that the proposed new algorithm is effective to solve the combinatorial optimization problems. Ye et al. (Ye et al. 2017) also suggested an improved ACO algorithm for tackling constraint-satisfaction problems and obtained the desired results.

In this study, two stiffener configurations are optimized for bearing blast loads. The modified ant colony optimization algorithm (MACO) which introduces the mass constraint factor to the pheromone update function and integrates the idea of crossover and mutation was proposed to search for the best possible stiffener layout under different loading cases. The article is organized as follows. Following this introduction section, the optimization problem is described in Sect. 2. Then, the modified MACO for design of stiffener configuration is depicted in Sect. 3. The optimization for the stiffened plates under blast loading and the discussion of results are presented in Sect. 4. Finally, some conclusions are drawn in Sect. 5.

2 Optimization problem and mathematical modeling

2.1 The stiffened plates and finite element modeling

In this study, we aimed to optimize two new kinds of stiffened plates, as shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1 also shows the size of stiffened plates, in which the front plate has a square shape with L × L = 250 mm × 250 mm, the thicknesses of the plate and the stiffener are the same as T = 1 mm, the height of the stiffener is H = 10 mm.

The numerical simulations were conducted by using explicit nonlinear finite element (FE) code LS-DYNA 971. The effective area of stiffened plates exposed to the impulsive load was 250 mm × 250 mm (Fig. 1a). The boundaries of the plate were fully fixed through nodal constraints. In the FE modeling, the Belytschko-Tasy shell elements were used for both the stiffeners and plate (Belytschko et al. 1984). Automatic single surface contact was used for the steel plates. A convergence study revealed that the mesh size of 2 mm was sufficient to balance the simulation accuracy and computational efficiency.

In the FE simulations, the stiffened plates were modeled by LS-DYNA material type 3. For the steel used in this study, the strain rate effect was considered by using the Cowper and Symonds model (Karagiozova et al. 2009). Thus, the yield stress was calculated as follows:

where \( {\sigma}_0^{\prime } \) is the dynamic flow stress, σ0 is the initial yield stress, \( \dot{\varepsilon} \) is the equivalent strain rate, and the \( \dot{\varepsilon_0} \) and q values are experimental constants determined from the dynamic tensile test results, there \( \dot{\varepsilon_0}=40{s}^{-1}\kern0.5em \)and q = 5.

The material properties of the mild steel include the density ρ = 7800 kg/m3, Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.3, Young’s modulus E = 210 GPa, and the static yield stress σ0 = 300 MPa (Goel et al. 2015; Karagiozova et al. 2009).

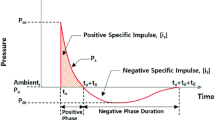

As mentioned in the introduction, blast impact is very complicated in nature, which can be affected by many factors, placing significant challenge in modeling a blast process entirely and exactly. In order to balance the modeling efficiency and accuracy, many researchers have simplified the blast loading according to the different purposes of the study. Since we would like to restrict our attention on the design methodology of stiffener layout for plates against blast loading, a uniformly distributed blast loading without considering the fluid–structure interaction as suggested in literature (Karagiozova et al. 2009) was taken as an example. This simplified blast load is also a common method used by many researchers (Chung Kim Yuen and Nurick 2005; Kadid 2008; Nurick et al. 1996). It can be applied in terms of a uniform pressure pulse with a constant duration on the front plane of the stiffened plate (see Fig. 2). Specifically, the pressure is described mathematically as follows (Karagiozova et al. 2009)

where p0 is the initial pressure, t denotes decaying time with a decay period of t0 = 0.002 ms. Obviously, the pressure decays exponentially.

The impulse I0 can be then defined as,

where L is the length of the stiffened plates, and the unit of the impulse is Ns.

2.2 Validation of FE model

As no in-house experiments for the stiffened plates available, the model in the literature is a good way to validate the established FE model in this paper. Since the loading mode and modeling technique here are the same as those in the literature (e.g., Karagiozova et al. 2009; Nurick et al. 2009), the example in these two references were thus used to validate this present study. Nevertheless, these two references were about the sandwich panels; we thus verified the modeling method for the sandwich panels here. Note that while sandwich panel differs from the stiffened panel, the FE modeling technique, including rate dependence of material properties, elemental characteristics, loading and boundary conditions, is rather similar.

The specific verification details for sandwich panel are as follows. The established FE model was validated through comparison with the experiments of sandwich panel under the blast loads as reported in Karagiozova et al. (2009) and Nurick et al. (2009). The impulses used in the validation varied from 4.4 to 30.3 Ns. A comparison between the experimental results (Nurick et al. 2009) and the numerical predictions are shown in Fig. 3. It is clear that the FE modeling results match with the experimental results fairly well. Such a satisfactory correlation suggested that the established FE model can be used for the subsequent design studies on the stiffened plates.

Comparison between experiment results (Nurick et al. 2009) and FE simulation results

2.3 Definition of optimization problems

As a protective structure, the stiffened plate is expected to improve the safety of the targets behind it. Thus, the maximum deflection (D) of the center point of the plate is a key criterion to assess the structural resistance to blast loading, and thus was selected to be the objective function. In addition, the mass of the plate is constrained within a certain value (M∗).

Taking the radial diagonal configuration as an example (Fig. 4), each stiffener is regarded to be a design variable. Since the structure considered here is one-eighth symmetric, the design domain can be represented by 13 design variables as denoted by xi (i = 1, 2, …, n). By assigning different thicknesses to each design variable, different material distributions and topological configurations can be characterized for achieving optimal protection performance. This study will explore two design scenarios, namely 0-1 thickness and multithickness designs. For the 0-1 thickness design, x1, x2, …, xn can be either 0 or 1, where 1 denotes the presence of a stiffener member, while 0 represents the absence. For the multithickness design, the design space is set to be R = {0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, …, 2.0}, meaning that any of the design variables x1, x2, …, xn can vary from 0 to 2.0 mm with a discrete increment of 0.1 mm.

3 MACO algorithm

The topographical optimization of stiffened plates involves presence/absence of stiffeners in terms of the stiffener thickness. For such problems, parametric modeling method and discrete intelligent optimization provide us with an effective solution. A MACO-based algorithm is presented here for optimizing stiffener configuration, in which the discrete variables were adopted to represent the topography of stiffeners.

3.1 The ACO algorithm

Ant colony algorithm (Chen et al. 2017) is one kind of bionic evolutionary algorithm, which is inspired by the foraging behavior of ants. In nature, the ants can always find the shortest path from their nest to the food source. Figure 5 illustrates a foraging process of ants.

The ants spread pheromone when they walk, and the pheromone decreases gradually with time. Ants will choose the path with large concentration of pheromone. The higher the concentration of pheromone on the path, the greater the probability of being chosen by other ants. The more ants walk on this path, the higher the concentration of pheromone on the path. Finally, after a period of operation, a shortest path may be repeated by most ants. Ant colony algorithm is an abstract of the biological ant colony.

In essence, the problem studied in this paper can be considered to be a nonlinear integer programming problem through some changes, which can be described as:

where x is the vector of n design variables, D(x) is the maximum deflection at the center point of the plate, M(x) is the mass of the stiffened plate, M∗ is the mass of the original stiffened plate with a uniform plate thickness of 1.0 mm, and w is the mass fraction predefined for the candidate solution. (ai, bi) is the lower and upper bounds of design variable xi, Z is an integer space. The number of possible values of xi is li = bi − ai + 1, xi has li nodes. Each variable takes a value to form a solution. In this paper, it is assumed that ai = 0 and all li are the same. If xi takes the mi-th node, the corresponding solution is:

Suppose ai = 0, so the feasible solution space is shown in Fig. 6.

Beginning with the first variable, each ant selects a point within the domain of the corresponding variable. Then, a route that corresponds to a solution vector x is completed after the n choices of an ant. From the above step, we have learned that the selection of ants according to the concentration of the pheromone. So, a l × n matrix Tau was constructed to be the corresponding pheromone matrix. The number of rows is equal to the number of discrete values assigned to each variable. The number of columns is equal to the number of variables. A component of Tau is denoted to be τij, which is the amount of pheromones left on the ith point within the domain of the jth variable. Each ant begins its trip from the first variable x1 and completes a route by going through all the other variables. For each ant, the probability of choosing the ith point within the domain of the jth variable is denoted by pij as follows:

Equation (6) follows the format of conventional transition probability, that is, τij is used to represent the attraction intensity of a point.

After one trip, each ant leaves a pheromone increment ∆τij upon each point that it went through. We calculate ∆τij using the ant cycle system model as:

where D is the objective function value in the design, which corresponds to the route of an ant, and Q is a constant that represents the pheromone value. The lower the value of the objective function is, the larger the pheromone increment is.

In the new trip, the point with more pheromones has a more positive effect on directing the search of an ant. The pheromones update method is provided as follows:

where ρ is a constant below 1 and presents the evaporation rate. The larger the ρ, the stronger the forgetting effect. Hence, it is possible for ants to explore a new area in the new round.

3.2 A MACO algorithm

Obviously, the explosion-proof performance of the stiffened plate is indeed closely related to its mass. And the optimum distribution of the stiffeners may also be closely related to the mass of stiffened plate. To investigate the relationship between the optimum distribution of the stiffeners and their mass constraints, the 0-1 design of the stiffened plate with radial diagonal configuration (see Fig. 4) which is introduced in the Sect. 2.3 was exemplified here. In this study, four cases were considered for different mass constraints, i.e., w = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5. So, we performed the numerical analysis for all the 4096 possible designs which satisfying the mass constraint w ≤ 0.5 for 0-1 design. The maximum deflection of the center point of the plate (D) of these designs are depicted in Fig. 7. Generally speaking, a large mass ratio w can obtain a smaller D. Specifically, the optimal solutions with the mass constraint w = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 are all close to the mass constraints, but not exactly on the constraint’s boundary as marked in Fig. 7. This is due to the discrete property of this binary topology optimization problem. For this reason, the optima tend to be located on the boundary of the mass constraint in the feasible design space. To accelerate the optimization process, the mass effect was considered in the pheromone update function of MACO. By pushing the optimal solution to the mass constraint boundary, it provides a higher chance of finding the optimum solution. Therefore, for the MACO algorithm, the pheromone increment ∆τij can be calculated by

In addition, in order to prevent the algorithm from being prematurely trapped in a local optimum, we use the elite tactic for pheromone update. In other words, only the paths ranked in top n (the number of elite ants) have the opportunity to leave a pheromone increment.

Another modification is to integrate the crossover and mutation into the ant colony optimization algorithm. After the ant colony completes a cycle, a new solution matrix Tabu with m routes generated by the m ants is obtained. A cross operation is then carried out between a certain numbers of routes randomly selected from the newly solution matrix Tabu according to the cross probability Pc. Here, we adopt the standard single-point crossover (Li et al. 2016); it can be briefly described as follows: one cross point is randomly arranged in the two individual coding strings which need to be paired with each other, and then carried through the change of some genes (Fig. 8). The numerical experiments show that the cross probability Pc set to 0.6 has the best results. So, Pc = 0.6 was adopted in this study.

Then, some gene values of routes in the solution matrix are changed according to the probability of mutation Pm for the new solution matrix after the crossover, which results in new routes. In this study, the value of one locus, according to the mutation probability Pm, is randomly assigned within the allowable range of the locus in the mutation operation (Fig. 9). The numerical experiments show that the mutation probability Pm set to 0.01 exhibits the best results. So Pm = 0.01 is adopted here.

In this way, the crossover and mutation operations are integrated into the MACO algorithm, which can increase the diversity of solutions, thereby enhancing the ability to avoid the algorithm from falling into and being trapped in a local optimum. This largely improved the performance of the conventional ACO algorithm.

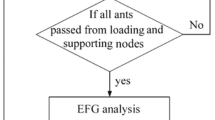

The MACO algorithm for designing the stiffened plate is illustrated in Fig. 10, which can be described in detail as follows:

-

Step 1

Define the optimization problem of stiffened plate, including the objective/constraint functions, and design variables and design space. In this study, the wall thickness of stiffeners x = [x1, x2, …, xn]T is regarded as the design variables in a discrete form, the maximum deflection of the center point of the plate (D) is set to be the objective function, and structural mass M(x) to be the constraint functions.

-

Step 2

Initializations of MACO algorithm. Determine the number of loops ncmax for the search of ants, termination condition, ant size m, pheromone matrix Tau, and solution matrix Tabu with m routes which generated by the m ants. The pheromone value Q, evaporation rate ρ, cross probability Pc, and mutation probability Pm are given. Provide an arbitrary initial domain for each variable: xi ∈ [ai, bi].

-

Step 3

Set the loop number nc ← 0. Thereafter, randomly generate m routes under the constraints. Each route corresponds to a solution vector x that controls the design variables (thicknesses). According to the solution vector, the corresponding FE model of stiffened plate is updated and the FE analysis is conducted to obtain the objective and constraint function values. Update the pheromone matrix Tau according to (8) and (9), find the shortest route.

-

Step 4

Beginning from x1 to xn, each ant selects one point in the domain of the corresponding variable based upon the transition probability pij (i = 1, 2, …, l + 1; j = 1, 2, …, n) calculated by (6). After the ant colony completes a cycle, a new solution matrix Tabu is obtained.

-

Step 5

Update the solution matrix Tabu by the following operation: (1) crossover of the solution matrix Tabu to generate new routes; (2) mutation of the new solution matrix after crossover, resulting in new routes.

-

Step 6

For the nc-th loop, according to the solution vector, the corresponding FE model of stiffened plate is updated and the FE analysis is conducted again to obtain the new objective and constraint function values. Replace the worst route of the nc-th loop by the best route of the last loop. Update the shortest route, and update the pheromone matrix Tau according to (8) and (9). Let nc ← nc + 1.

-

Step 7

If the termination criterion is not satisfied, go back to step 4. Otherwise, determine the minimal function value Dmin of stiffened plate among all the loops.

4 Optimization for the stiffened plates

4.1 Radial diagonal configuration

The MACO was used to distribute the discrete thickness of stiffeners according to the working conditions, in which the algorithmic parameters are set to be m = 100, Q = 50, ρ = 0.8, Pc = 0, and Pm = 0.01. Once the solution was no longer rising for 15 reproduction trials, or the maximum generation was greater than the preset trial times (i.e., ncmax = 100), the termination criterion was reached.

The stiffened plate with radial diagonal configuration is shown in Fig. 4 which is introduced in Sect. 2.3. Since the structure considered here is in one-eighth symmetry, the problem can be modeled in terms of 13 design variables as shown in Fig. 4. In this study, four design cases were considered for different mass constraints, i.e., w = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5.

Taking the impulse loading 15 MPa as an example, the thickness distribution of the optimal 0-1 and multithickness designs are summarized in Table 1. In order to improve efficiency and save calculating cost, the optimum solution of 0-1 designs is used as one of the initial population of multithickness designs under the same mass constraints (Hassanat et al. 2018; Kazimipour and Li et al. 2014; Meng et al. 2016a; Zhang and Lu 2007).

Figure 11 compares the performance D under different mass fractions. Figure 12 displays the decrease rate in D for stiffened plates in comparison with the flat plate. From Fig. 11, it can be seen that for the maximum deflection of the center point (D), multithickness design < 0-1 design < initial stiffened plate < flat plate subject to the same mass. Taking mass fraction w = 0.5 as an example, Fig. 12 shows that the D for the initial stiffened plate, optimal 0-1 and multithickness designs were respectively 12.66%, 23.65%, and 33.22% lower than that of the flat plate.

For facilitating the observation, the deflection contours of all the plates were plotted in the developed planes under mass fraction w = 0.5 in Fig. 13. Because of the symmetry of the structure, only one fourth of the total field was displayed. Note that the initial stiffened plate, the 0-1 and multi-thickness designs all decrease the deflection range of the plate. Of them, the multithickness design was decreased most. All of these have illustrated that for the explosion-proof performance, multithickness design > 0-1 design > initial stiffened plate > flat plate subject to the same mass. This implies that compared with the uniform stiffened plate, the multithickness designs can provides more logical material distribution for reinforcing the plate against the blast loading.

Through comparison of these four different mass fractions, it can be found that the decrease rate of D increased with mass fraction for the stiffened plates (see Fig. 12). This is because, as the mass fraction increased, the design space becomes larger; thus, the effect of optimization was enhanced. In other words, a greater mass fraction engages more design variables so as to achieve better explosion-proof performance.

As can be seen from Fig. 13, the deformation was mainly concentrated in the central area and gradually decreased from the center to the four sides. And as shown in Table 1, the optimum designs placed more reinforcement materials in the central regions for both the 0-1 and multithickness designs. Also, the displacements at the four corners are relatively small under the present blast load. From topology optimization perspective, the material contribution to the center displacement from these areas was rather marginal. This explains why there are no stiffeners at the four corners of the plate in 0-1 and multithickness designs as shown in Table 1. From Fig. 13 and Table 1, the results indicate that in order to get higher explosion-proof performance, the material was mainly distributed in the key deformed regions for both the 0-1 and multithickness designs. Conversely, thinner material was distributed in the undeformed or slightly deformed areas. Thus, it is effective to place more stiffener’s materials in the central area than around the four corners of the plates.

Further, it can be regarded that the optimal topography was derived by adding the stiffeners to a base configuration of ( ) in both the 0-1 and multithickness designs with different mass fractions respectively, as shown in Fig. 14. Structure (

) in both the 0-1 and multithickness designs with different mass fractions respectively, as shown in Fig. 14. Structure ( ) can be used to support the plate, resist deformation, and transfer loads, which can be viewed as the key reinforcement pattern of the stiffened plate. Hence, the stiffened plate may be designed on the basis of this layout in the future study.

) can be used to support the plate, resist deformation, and transfer loads, which can be viewed as the key reinforcement pattern of the stiffened plate. Hence, the stiffened plate may be designed on the basis of this layout in the future study.

From Table 1, it can be further found that the optimal configurations of multithickness design with the different mass fractions have a fairly interesting common feature in ( ); this is that all have a thick x4 (see Fig. 15). This is because a thick x4 is beneficial to support the plate against the deformation under blast loading.

); this is that all have a thick x4 (see Fig. 15). This is because a thick x4 is beneficial to support the plate against the deformation under blast loading.

To check the correctness of the proposed MACO algorithm, the 0-1 design of the stiffened plate with radial diagonal configuration (see Fig. 4) was taken as an example here. Four cases were considered for the different mass constraints, i.e., w = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5. For the original and modified ACO, the ant size m = 100, pheromone value Q = 50, and evaporation rate ρ = 0.8 were set. For GA, a population size of 100 was used. For all these three algorithms, the maximum generation ncmax was 100, the crossover probability Pc = 0.6, and the mutation probability Pm = 0.01 were adopted here.

The optimization results the 0-1 design obtained from the GA, original ACO and modified ACO were compared in Table 1. The success rate represents how many runs are required to achieve a global optimum out of ten repeated runs, which was used to evaluate the performance of each algorithm. From Table 2, it is seen that the modified ACO was more robust in terms of the worst and average objective values and exhibited a high success rate. Also, the modified ACO algorithm can reduce the computational cost by reducing the number of FE analyses. Thus, we can draw the conclusion that modified ACO is able to efficiently produce optimal designs and can be used for subsequent optimization.

4.2 Surrounding diagonal configuration

The stiffened plate with surrounding diagonal configuration is shown in Fig. 16. The 11 inner stiffener’s walls were taken to be the design variables due to the one-eighth symmetry. Four cases were considered herein again for the different mass fraction constraints, i.e., w = 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5. Also taking an impulse loading 15 MPa as an example, the thickness distribution of the optimal 0-1 and multithickness designs are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 17 compares the performance D under different mass fractions. Figure 18 graphs the decrease rate in D for the stiffened plates in comparison with the flat plate. From Figs. 17 and 18, it can be seen that regarding the maximum deflection at the center point (D), multithickness design < 0-1 design < initial stiffened plate < flat plate subject to the same mass. Taking mass fraction w = 0.5 as an example, the deflection contours of all the plates were plotted in the developed planes in Fig. 19. Again, the initial stiffened plate, the 0-1 and multithickness designs all decreased the deflection range of the plate. Among them, the multithickness design decreased most. This is another example that makes clear our earlier finding that in comparison with the uniform stiffened plate, the multithickness design can provide a better material distribution against blast loading.

As can be seen from Fig. 19 and Table 3, the results again indicate that in order to obtain a higher explosion-proof performance, the material is largely distributed in the main deformed regions for both the 0-1 and multithickness designs. Conversely, thinner material is distributed in the nondeformed or slightly deformed areas. Again, the optimal configurations under the different mass fractions can also be obtained by adding stiffener to a base configuration of ( ) (see Fig. 20). Similarly to the radial diagonal configuration, the optimal multithickness layouts under the different mass fractions have a common configurational feature in (

) (see Fig. 20). Similarly to the radial diagonal configuration, the optimal multithickness layouts under the different mass fractions have a common configurational feature in ( ), i.e., a thick x4.

), i.e., a thick x4.

Figure 21 compares the optimal configurations of the two stiffened plates in the 0-1 and multithickness designs. For these two stiffened plates, it was observed that all the optimum designs have a common key reinforcement layout that connects to the fixed boundaries ( ) for supporting the plate against the blast deformation. Then, the other stiffeners can be viewed to be added on the basis of this key reinforcement. And the locations of the other stiffeners start from the center with a low mass ratio. With increase in the mass fraction, the allocation of stiffeners expands outward from the center. For a stiffened plate with fixed boundary, the reinforcement layout from the center to the surrounding edges is logic. Through optimizing these two stiffened plates, it can be found that first, it would be effective to have a key reinforcement layout, and then to add other stiffeners onto the key reinforcement; second, for a stiffened plate with fixed boundary such as the one studied here, priority should be placed to the reinforcement in the middle region instead of the corner region of the plate.

) for supporting the plate against the blast deformation. Then, the other stiffeners can be viewed to be added on the basis of this key reinforcement. And the locations of the other stiffeners start from the center with a low mass ratio. With increase in the mass fraction, the allocation of stiffeners expands outward from the center. For a stiffened plate with fixed boundary, the reinforcement layout from the center to the surrounding edges is logic. Through optimizing these two stiffened plates, it can be found that first, it would be effective to have a key reinforcement layout, and then to add other stiffeners onto the key reinforcement; second, for a stiffened plate with fixed boundary such as the one studied here, priority should be placed to the reinforcement in the middle region instead of the corner region of the plate.

However, the design space chosen in this paper is maybe not the best possible one, and there will be other and better design space. In this paper, we mainly focused on the design methodology of stiffener layout for plates against blast loading. And some useful advices are provided for traditional layout of the stiffeners.

5 Conclusion

This study explored the two novel reinforcement configurations of stiffened plates. The modified ant colony optimization (MACO) algorithm that introduces the mass constraint factor to the pheromone update function and integrates the idea of crossover and mutation was implemented to optimize the material distribution of stiffeners in a discrete form of either 0-1 or multithickness strategy. The optimal distribution of stiffener thicknesses has proven promising to enhance explosion-proof performance of stiffened plates. Within its limitation, the following conclusions can be drawn from this study as follows:

-

1.

The explosion-proof performances of all the optimized multithickness designs are substantially higher than those of the 0-1 design and initial design under the same mass fraction. This is because the multithickness design can make best use of the allowed mass. In other words, more sophisticated material distribution for the stiffeners is an effective way to enhance the explosion proof performance of structures.

-

2.

Note that the optimum designs all have a common key reinforcement to connect from the center to the fixed edges for supporting the plate against the blast-induced deformation. It could be a feasible design procedure to first determine a key reinforcement layout, and then to add other stiffeners onto it. Allocation of more materials in the middle instead of the corner regions is an effective way to enhance the explosion-proof performance of the stiffened plates.

-

3.

These optimization results demonstrated that the proposed configurations and optimization method are fairly effective and can provide a useful tool for generating novel protective structures. Further, it is rather simple to be implemented computationally.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations in this work. First, a uniformly distributed blast loading without considering the fluid–structure interaction was applied to simplify the loading process and decrease the computational cost, which may not be able to capture the real blast-load effects to a certain extent (Kambouchev et al. 2006). Second, since the range of blast loading considered here was given without reaching the failure threshold, the effects of plate/stiffener fracture was not considered in this study. In real life, failure might occur in both plate and stiffeners, and it is necessary to consider its effects on design optimization. Nevertheless, the methodology established in this study would be of considerable implication to the incorporation of these issues for design optimization.

References

Belytschko T, Lin JI, Chen-Shyh T (1984) Explicit algorithms for the nonlinear dynamics of shells. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 42:225–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7825(84)90026-4

Chandra Mohan B, Baskaran R (2012) A survey: ant Colony optimization based recent research and implementation on several engineering domain. Expert Syst Appl 39:4618–4627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2011.09.076

Chen Z, Zhou S, Luo J (2017) A robust ant colony optimization for continuous functions. Expert Syst Appl 81:309–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2017.03.036

Chung Kim Yuen S, Nurick GN (2005) Experimental and numerical studies on the response of quadrangular stiffened plates. Part I: subjected to uniform blast load. Int J Impact Eng 31:55–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2003.09.048

Demirel NÇ, Toksarı MD (2006) Optimization of the quadratic assignment problem using an ant colony algorithm. Appl Math Comput 183:427–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2006.05.073

Ding Q, Hu X, Sun L, Wang Y (2012) An improved ant colony optimization and its application to vehicle routing problem with time windows. Neurocomputing 98:101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2011.09.040

Dorigo M, Gambardella LM (1997) Ant colony system: a cooperative learning approach to the traveling salesman problem. IEEE Trans Evol Comput 1:53–66. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.585892

Fang J, Sun G, Qiu N, Kim NH, Li Q (2016) On design optimization for structural crashworthiness and its state of the art. Struct Multidiscip Optim 55:1091–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-016-1579-y

Fang J, Sun G, Qiu N, Steven GP, Li Q (2017) Topology optimization of multicell tubes under out-of-plane crushing using a modified artificial bee colony algorithm. J Mech Des 139:071403. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4036561

Furqan A, Santosa SP, Putra AS, Widagdo D, Gunawan L, Arifurrahman F (2017) Blast impact analysis of stiffened and curved panel structures. Procedia Eng 173:487–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.12.070

Goel MD, Matsagar VA, Gupta AK (2015) Blast resistance of stiffened sandwich panels with aluminum cenosphere syntactic foam. Int J Impact Eng 77:134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2014.11.017

Goetz J, Tan H, Renaud J, Tovar A (2012) Two-material optimization of plate armour for blast mitigation using hybrid cellular automata. Eng Optim 44:985–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305215X.2011.624182

Hani Y, Amodeo L, Yalaoui F, Chen H (2007) Ant colony optimization for solving an industrial layout problem. Eur J Oper Res 183:633–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2006.10.032

Hassanat A, Prasath V, Abbadi M, Abu-Qdari S, Faris H (2018) An improved genetic algorithm with a new initialization mechanism based on regression techniques. Information 9:167. https://doi.org/10.3390/info9070167

Kadid A (2008) Stiffened plates subjected to uniform blast loading. J Civ Eng Manag 14:155–161. https://doi.org/10.3846/1392-3730.2008.14.11

Kambouchev N, Noels L, Radovitzky R (2006) Nonlinear compressibility effects in fluid-structure interaction and their implications on the air-blast loading of structures. J Appl Phys 100:063519. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2349483

Karagiozova D, Nurick GN, Langdon GS (2009) Behaviour of sandwich panels subject to intense air blasts—part 2: numerical simulation. Compos Struct 91:442–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.010

Kazimipour B, Li X, Qin AK (2014) A review of population initialization techniques for evolutionary algorithms. In: Evolutionary computation, pp 2585–2592

Kumar KCN, Gupta G, Lakhera S, Shaikh A (2015) Structural optimization of composite stiffened panel of a transport aircraft wing using CAE tools. Mater Today Proc 2:2588–2594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2015.07.213

Langdon GS, Yuen SCK, Nurick GN (2005) Experimental and numerical studies on the response of quadrangular stiffened plates. Part II: localised blast loading. Int J Impact Eng 31:85–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2003.09.050

Li M, Qianting L, Meiqiong M, Sicong L (2016) Optimization and application of single-point crossover and multi-offspring genetic algorithm. Int J Hybrid Inf Technol 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.14257/ijhit.2016.9.1.01

Liao TW, Su P (2017) Parallel machine scheduling in fuzzy environment with hybrid ant colony optimization including a comparison of fuzzy number ranking methods in consideration of spread of fuzziness. Appl Soft Comput 56:65–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.03.004

Liu H, Li B, Yang Z, Hong J (2017) Topology optimization of stiffened plate/shell structures based on adaptive morphogenesis algorithm. J Manuf Syst 43:375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2017.02.002

Louca LA, Pan YG, Harding JE (1998) Response of stiffened and unstiffened plates subjected to blast loading. Eng Struct 20:1079–1086

Maniezzo V, Colorni A (1999) The ant system applied to the quadratic assignment problem. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng 11:769–778. https://doi.org/10.1109/69.806935

Meng X, Dong L, Li Y, Guo WW (2016a) A genetic algorithm using K-path initialization for community detection in complex networks. Clust Comput 20:311–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-016-0698-y

Meng Y, Li B, Wang Y (2016b) Structure design of new airtight blast door based on topology and shape optimization method. Geotech Geol Eng 34:703–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-016-9981-1

Ning JG, Song WD, Wang C, Wang J (2006) Impact perforation of stiffened steel plates by rigid projectiles. Key Eng Mater 306-308:303–308. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.306-308.303

Nurick GN, Gelman ME, Marshall NS (1996) Tearing of blast loaded plates with clamped boundary conditions. Int J Impact Eng 18:803–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(96)00026-7

Nurick GN, Langdon GS, Chi Y, Jacob N (2009) Behaviour of sandwich panels subjected to intense air blast—part 1: experiments. Compos Struct 91:433–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.009

Rudrapatna NS, Vaziri R, Olson MD (2000) Deformation and failure of blast-loaded stiffened plates. Int J Impact Eng 24:457–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(99)00172-4

Sheyka MP, Altunc AB, Taha MMR (2012) Multi-objective genetic topological optimization for design of blast resistant composites. Appl Compos Mater 19:785–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10443-011-9244-5

Solimanpur M, Vrat P, Shankar R (2004) Ant colony optimization algorithm to the inter-cell layout problem in cellular manufacturing. Eur J Oper Res 157:592–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0377-2217(03)00248-0

Sun G, Liu T, Fang J, Steven GP, Li Q (2017) Configurational optimization of multi-cell topologies for multiple oblique loads. Struct Multidiscip Optim 57:469–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-017-1839-5

Sun G, Liu T, Huang X, Zhen G, Li Q (2018) Topological configuration analysis and design for foam filled multi-cell tubes. Eng Struct 155:235–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2017.10.063

Ye K, Zhang C, Ning J, Liu X (2017) Ant-colony algorithm with a strengthened negative-feedback mechanism for constraint-satisfaction problems. Inf Sci 406-407:29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2017.04.016

Zhang Y, Lu J (2007) A novel improved adaptive genetic algorithm for the solution to optimal assignment problem. Int J Syst Control 2: 253–261.

Zheng C, Kong X-s, Wu W-g, Liu F (2016) The elastic-plastic dynamic response of stiffened plates under confined blast load. Int J Impact Eng 95:141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2016.05.008

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51621004), National Natural Science Foundation of China (51575172, 51475155), and the Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory for Strength and Vibration of Mechanical Structures of Xi’an Jiaotong University (SV2017-KF-24). Dr. Guangyong Sun is a recipient of Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) in the University of Sydney. Dr. Jianguang Fang is a recipient of University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Fred van Keulen

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Sun, G., Fang, J. et al. Topographical design of stiffener layout for plates against blast loading using a modified ant colony optimization algorithm. Struct Multidisc Optim 59, 335–350 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-018-2171-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-018-2171-4