Abstract

We develop an intra-household bargaining model to examine the feedback effect of household fertility decisions on gender bargaining power. In our model, the household balance of power is endogenously determined reflecting social interactions, i.e., the fertility choices by the other couples in society. We show the presence of multiple equilibria in fertility outcome: one equilibrium characterized by patriarchal society with a high fertility rate, and another in which women are sufficiently empowered and the fertility rate is low. In other circumstances, this study also demonstrates a positive relationship between female wage rates and the fertility outcomes. Finally, we discuss its policy implications, comparing the effects of two family policies: the child allowance and the subsidies for market childcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the influential work by Konrad and Lommerud (2000), many theoretical studies on family bargaining have endogenized the power balance within a family (Vagstad 2001; Lundberg and Pollak 2003; Basu 2006; Rainer 2008). Recently, the relationship between endogenous bargaining power and fertility has begun to be analyzed in the studies of household decisions.Footnote 1 On one strand, it is depicted that the individual choices affect the future power balance of themselves. Iyigun and Walsh (2007) showed that the fertility rate is reduced by an increase in women’s bargaining power, which depends upon the premarital educational investment.Footnote 2 On the other strand, some authors explain that the bargaining power between sexes is influenced though social interactions. Doepke and Tertilt (2009) and Fernandez (2010) demonstrated the negative relationship between fertility and women’s autonomy in models where a man’s vote for women’s liberation may alter the balance of gender power of future couples including his offspring.Footnote 3

Although their analyses are recognized as pioneering research in the field of development and population economics, they still do not consider that the fertility decisions themselves affect the economic strength of women. Fertility decisions affect the choice of women’s labor supply since childbearing necessarily keeps women away from earning activities, which in turn, leads to a wider gender gap in society. Cigno (2008, 2012) pointed out that only the existence of the prenatal period can lead women into an economically unfavorable position at cooperative marriage, followed by their lower outcome of intra-family distribution.Footnote 4 The purpose of this paper is to construct a simple family bargaining model, taking into account the effect of having children on women’s economic vulnerability.

We set two distinct features in the intra-household decision making model. Our main feature is that gender bargaining power is endogenously determined by social norm or peer pressures, with an aim of exploring the feedback effect of fertility decisions on the bargaining power. In our model, social externalities impose certain gender roles to individuals in the marriage market.Footnote 5 Their balance of power in the marriage market depends on the ratio of incomes earned if they have the average number of children per household. As long as the level of women’s bargaining power bears some relation to their fertility choices, it is worth investigating fertility and the balance of power between sexes in a model where both variables are endogenized interdependently.

The other feature is that the family members negotiate the distribution within themselves in the presence of conflicting parental preferences over the number of their children.Footnote 6 Figure 1 plots the young women’s average ideal number of their children against that of young men of OECD countries in Europe (except for the unavailable data of Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland), using the cross-sectional data set of Testa (2006). The data suggest that the preferences on fertility outcomes are not necessarily the same between men and women. For example, women are likely to prefer a larger family size than men in Northern Europe.

As Fig. 1 indicates, family-size preferences vary not only across countries but between sexes in one country, and thus, the traditional common preference approach is not strictly enough for the study of family behaviors including fertility choice. In order to incorporate the conflicting parental preferences into fertility analysis, we follow the bargaining analysis by Chiappori (1988; Chiappori (1992) in which family members always make efficient decisions according to a particular decision rule of their marriage.Footnote 7

We show that when husbands wish to have more children than their wives do, the interaction between fertility outcome and gender bargaining power leads to multiple equilibria; one equilibrium characterized by a patriarchal society with a high fertility rate, and another in which women are sufficiently empowered, keeping their fertility rate low. Using our model, in the opposite but occasionally observed situation where wives prefer a larger family size than their husbands, it is also theoretically possible to achieve improvements in women’s labor conditions through their wage increases and an increase in fertility rate in spite of the higher opportunity cost of childrearing. This result is in contrast to the traditional opportunity cost theory that explains demographic transition by the negative relationship between women’s wage rates and their fertility.Footnote 8 In some countries, we observe the environment in which both fertility rates and female wage rates are relatively high, and our finding can partly explain these observations.Footnote 9 Moreover, this framework provides some new implications for the effects of different family policies; the subsidies for bought-in childcare increases the bargaining power of women, thereby the fertility rate may fall, while the child allowance has no such effect, so that it increases fertility rates.Footnote 10 Our model, which includes the interactions between fertility and bargaining power nicely, properly acts to derive these policy implications.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents an intra-family decision-making model with endogenous bargaining power. Section 3 presents the main results. Section 4 discusses the effectiveness of family policies, and Section 5 contains brief concluding remarks.

2 Model

Consider an economy consisting of two types of groups, \(i\in \left\{ {f,m} \right\}\), men (denoted by m) and women (denoted by f). Although preferences differ between the groups, they are all assumed to have identical preferences within their group. Two individuals out of each group form a monogamous family. After marriage, they decide on the number of children. Their conflicting preferences are resolved through cooperative bargaining based on their bargaining power. In our model, such bargaining power, in turn, will be affected by the other couple’s fertility decisions through social norm or peer pressures regarding the gender roles such as women’s participation in the labor market.

2.1 Preferences

The individual i’s utility function is

where c and n denote the level of consumption by parents and the number of their children, respectively. The subutility of v i (n) stands for individual i’s utility perceived from n.Footnote 11 The husband and wife bargain over their own consumption and the number of their children to maximize the welfare function:

where \(\theta \in \left[ {0,1} \right]\) is the wife’s bargaining power in the household. This means that in one extreme case, θ = 0, represents the case where the household solely maximizes the husband’s utility function. In the other extreme, θ = 1, the household preference corresponds to the wife’s.

2.2 Constraints

We assume here that each individual’s total available hours are normalized to unity, and that only women take the responsibility for parental attention.Footnote 12 Because household members do not perceive utility from leisure, her hours are allocated between child care and market work as 1 = L + t, where L is the actual labor supply of women and t is the total parental attention to n children. The husband supplies inelastically one unit of time in the labor market, so that we simply denote his labor income by his wage rate, Y.

Instead of being busy with childrearing, the wife can substitute her parental attention by purchasing the market goods for childcare, x. The household’s budget constraint is c + px = wL + Y, where p is the price for bought-in childcare and w is women’s wage rates, respectively.

The number of children is given by

where \({\partial n} / {\partial x>0}\), \({\partial^2n} / {\partial x^2<0}\), \({\partial n} / {\partial t>0}\), and \({\partial^2n} /{\partial t^2<0}\). Even though women can substitute their time for childrearing with market goods, they are not perfectly substitutable since a child requires special maternal time.Footnote 13 Put differently, having another child requires women to leave the labor market for a certain period. In this paper, we also maintain the assumption that the household production function of childcare \(\phi \left( {x,t} \right)\) is characterized by constant returns to scale (CRS).Footnote 14 Under the CRS technology, the unit costs of having a child depends on relative prices only, which makes the analysis substantially simpler. The spouses minimize the cost of raising children, C = px + wt subject to Eq. 3, yielding input demand functions, \(x^\ast =\hat{x}\left( {p,w} \right)n\), \(t^\ast =\hat{t}\left( {p,w} \right)n\), and the fixed cost of having a child, \(q\left( {p,w} \right)=p\hat{x}{+w\hat{t}=C} / n\), where \(\hat{t}\left( {p,w} \right)\) and \(\hat{x}\left( {p,w} \right)\) are the per unit requirements of the mother’s time and market good for childcare, respectively. Making use of the unit cost for having a child, the household budget constraint can be rewritten as follows:

2.3 Household decision making

Given the level of the gender bargaining power, the household maximizes a weighted average of the husband and wife’s utility, subject to Eq. 4. Solving the welfare maximization problem, we have the first-order condition,

which depicts the fact that the cost of having a child in the household must be equal to the sum of the weighted individual marginal utilities for having a child. Equation 5 gives the fertility as a function of bargaining power and prices of childcare, \(n=n\left({\theta ;p,w}\right)\).

Note that the sign representing the effect of bargaining power on the number of children can be checked by the specification of each spouse’s utility functions as follows:

Equation 6 means that an increase in the wife’s bargaining power brings the household outcomes close to her fertility goal. When she prefers a larger family size than her husband, a rise in her autonomy increases the number of children, and vice versa. We can summarize the above arguments as follows:

Lemma 1

(Property of fertility outcomes) The sign of the effect of a rise in women’s bargaining power on the fertility rate is determined by the difference in the degree of parental preferences.

For further reference, we derive \(\theta =\xi \left( {n;p,w} \right)\) by solving the equation \(n=n\left( {\theta ;p,w} \right)\) for θ.

2.4 Endogenous gender bargaining power

This subsection defines the gender bargaining power. In most industrial countries, women have been obtaining almost the same rights as men. For example, they can invest enough in their human capital narrowing wage gap and participate in the labor market. In the households, women increase the autonomy of their decisions on the use of household resources such as family planning. They can now also choose to divorce and win custody and control their earnings and assets. Despite the growing liberation of women, there still exists considerable consciousness of gender issues in these countries. As Cigno (2008, 2012) pointed out, a commonly cited cause of this gender inequality is the fundamental gender difference of giving birth with an inevitable women’s leave from the labor market. Moreover, the blank due to childrearing in women’s career not only limits their own economic position but shapes the social pressure on the gender role, thereby weakening the position of other young women in their marriage.

In order to describe this situation, we assume that the wife’s intra-household bargaining power, θ, is determined in the marriage market, where individuals learn their gender roles through social interactions. The degree of women’s empowerment in the marriage market depends on the ratio of their labor income compared to that of men,Footnote 15 which is earned if the wife spends the same number of hours for domestic childcare as that of average one in each household. This means that the hours for market work which the society or the social norm of gender role expects women to supply is determined by subtracting the average parental attention, \(\overline {tn} \), from their endowed time normalized to one, as \(1-\overline {tn} \).Footnote 16 The couples in the marriage market (especially women) form their family by accepting this socially determined bargaining power, i.e., the balance of power between sexes is exogenous for each family, but endogenous on the societal level, and this is the “marriage market externality” in our model.Footnote 17 Hence, women’s bargaining power is represented by a continuous and differentiable function of

The assumption of θ(0) = 0 means that women have no autonomy in the household decision making if society expects them to devote the whole endowed time to childcare.

2.5 Equilibrium

We are now ready to define the equilibrium for our economy.

-

1.

Given the prices of goods, individuals’ wage rates, and the bargaining power, (p, w, Y, θ), the couples derive the unit cost of a child \(q=p\hat{x}\left( {p,w} \right)+w\hat{t}\left( {p,w} \right)\), and then maximize their welfare function given by Eq. 2, to obtain the fertility demand function:

$$\label{eq8a} n=n\left( {\theta ;p,w} \right) $$(8a) -

2.

In the marriage market, given the average maternal attention per household in society, \(\overline {tn} \), the bargaining power of women is determined to be \(\theta =\theta \left( {{w(1-\overline {tn} )} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w(1-\overline {tn} )} Y}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} Y} \right)\). From the homogenous marriages, the choices of household coincide with the average fertility and the average number of hours at domestic childcare in the equilibrium, i.e., \(\overline {tn} =\hat{t}n\). By substituting it into Eq. 7, we then have

$$\label{eq8b} \theta =\theta \left( {{w\left( {1-\hat{t}n} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w\left( {1-\hat{t}n} \right)} Y}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} Y} \right)=\psi \left( {n;p,w,Y} \right). $$(8b)

Finally, solving Eq. 8a and 8b allows us to derive fertility and bargaining power in the equilibrium, \(\left( {n^\ast ,\theta^\ast } \right)\).

Note that \(\theta =\psi \left( {n;p,w,Y} \right)\) is obviously decreasing with respect to \(n \left( {{\partial \psi } / {\partial n}=-{\left( {\theta ^\prime w\hat{t}} \right)} / Y<0} \right)\). This implies that having an extra child by other families decreases the bargaining power of young women in the marriage market. It leads to a rise in the required maternal attention, and thus reduces her labor supply. Since young couples determine their balance of power reflecting the other couples’ choices, the reduction in women’s expected labor income lowers their economic positions in marriage.

3 Comparative statics

This section analyzes the effects of changes in exogenous variables on fertility and endogenous bargaining power. In the discussion below, to make our analysis simple and apparent, we assume \(v_f \left( n \right)=av_m \left( n \right)\), implying that women’s preference on children is equal to men’s multiplied by a constant a > 0 for all n. As the effect of bargaining power on fertility outcome depends on the heterogeneity of the parental attitudes from Lemma 1, we study fertility and gender bargaining power in the following different cases; case 1 (a < 1) and case 2 (a > 1).Footnote 18

Before investigating the total effects of changes in exogenous variables, we explore their effect on \(\psi \left( {n;p,w,Y} \right)\) and \(\xi \left( {n;p,w} \right)\). Given the level of fertility outcomes, by differentiating ψ with respect to p, w, and Y, we have the following:

and

The sign of Eq. 9 is negative because an increase in the price of bought-in childcare leads to a reduction in expected female labor income due to a technical substitution of childcare, thereby lowering their bargaining power. In Eq. 10, we can find two effects according to a rise in women’s wage rates. The first term in brackets is the direct effect on expected female labor income that comes from the increased wage itself. The second term is positive, corresponding to the technical substitution effect. In sum, the expression of Eq. 10 is positive. Equation 11 shows that the women’s bargaining power is decreasing in the men’s wage rates.

Given the level of fertility outcomes, we can express the effect of exogenous variables on ξ by using the Shepherd’s lemma as follows:

and

From Lemma 1, we can interpret Eqs. 12–14 as the effects on fertility outcomes. Each of Eqs. 12 and 13 represents the negative effect on fertility because raising p or w induces an increase in the unit cost of having a child, while the fertility rate is not influenced by Y as in Eq. 14.

3.1 Case 1 (a < 1)

Case 1 represents a situation in which the men desire more children than women do. It is quite natural that women would hesitate to have many children in comparison to men considering their physical and mental strain attendant upon the frequent childbirth and the fact that the longer period of childrearing is likely to narrow the range of women’s occupational choices. This case is supported by many evidences focusing especially on developing countries, while some theoretical papers studying the conflict of preferences over fertility outcomes also assume this case.Footnote 19 In order to ensure an interior equilibrium, we make an assumption on the ideal family size of the husband.

Assumption 1

Let n i be the number of children achieved by maximizing solely the utility of individual \(i\in \left\{ {f,m} \right\}\) . Then, p and w satisfy the following condition:

Assumption 1 implies that the husband does not want so many children that his wife must spend all her time for childrearing, which seems to be plausible. Making use of Assumption 1, we have the following proposition.

Proposition 1

-

1.

When men prefer a larger family size than their wives, there exists at least one equilibrium.

-

2.

When men prefer a larger family size than their wives and there is an equilibrium such that \(\left. {{\partial \psi } / {\partial n}} \right|_{\left( {\theta^\ast ,n^\ast } \right)} <\left. {{\partial \xi } / {\partial n}} \right|_{\left( {\theta^\ast ,n^\ast } \right)} \) , we have at least three equilibria of fertility and bargaining power.

Proof of Proposition 1.1

For illustrative purposes, we provide a proof to go along with the graphical analysis by using Fig. 2a, b. From Lemma 1, a > 1 and the property of fertility function, we have \( n\left( {0;p,w} \right)=n_m \) and \( n\left({1;p,w} \right)=n_f \) as in Fig. 2a. Under the Assumption 1, \( \psi \left( {0;p,w,Y} \right)\le 1 \) and \( \psi \left( {1 / {\hat{t}};p,w,Y} \right)=\theta \left( {0 / Y} \right)=0 \), it is obvious that ψ and ξ intersect at least once as described in Fig. 2a. □

Proof of Proposition 1.2

Since \(n\left( {0;p,w} \right)=n_m \), \(n\left( {1;p,w} \right)=n_f \), \(\psi \left( {0;p,w,Y} \right)\) ≤ 1, \(\psi \left( {1 / {\hat{t}};p,w,Y} \right)\) = \(\theta \left( {0 / Y} \right)\) = 0 under Assumption 1, if there exists an equilibrium where the two curves cross at angles of \({\partial \psi } / {\partial n}<{\partial \xi } / {\partial n}\), applying the mean value theorem to \(\psi \left( {n;p,w,Y} \right)\) and \(\xi \left( {n;p,w} \right)\) allows us to obtain at least three equilibria. □

Figure 2b illustrates one particular subdivision of this case with the equilibria of E 1, E 2, and E 3.Footnote 20 Starting with a women’s bargaining power between θ 1 and θ 2, fertility outcome and bargaining power converge to the equilibrium of E 1. If the women’s initial bargaining power lies between θ 2 and θ 3, they now converge in E 3. Thus, the low fertility rate with a strong women’s say and the high fertility rate with low bargaining power are locally stable, while E 2 is unstable. These two stable equilibria characterized by fertility and bargaining power are partly consistent with the empirical evidence. Gustafsson (1992) found a negative relationship of fertility and women’s economic activities, using the micro-data of Germany, where men want a larger number of children as in Fig. 1. On the other hand, it is not observed in her results with the micro-data of Sweden in which the relationship of preferences is opposite.

Let us now consider the effect of a change in women’s wage rate. Suppose that the original economy is at a high fertility equilibrium, E 3, and there is an increase in the female wage rates. This will cause the curve representing \(\psi \left( {n;p,w,Y} \right)\) to shift upward and the curve representing \(\xi \left( {n;p,w} \right)\) downward from Eqs. 10 and 13. As a result, these shifts lead to a decrease in the number of children. Although the decline in fertility rate due to endogenous gender bargaining power is similar to the outcome in Iyigun and Walsh (2007), the economic mechanism behind these two results are different.Footnote 21 In our model, because of the heterogeneity in the spouses’ preferences for family size, an increase in women’s wage rates causes not only the negative effect due to the higher opportunity cost of having a child, but another negative effect of enhanced bargaining power of women, whose desired number of children is smaller than those of men.

These results in case 1 propose that the bargaining power between sexes may turn out to be a key factor in better understanding the demographic transition and shed new light on intra-household decisions, especially the hidden issue of family planning.

3.2 Case 2 (a > 1)

Many evidences indicate that men demand a larger family size than women do, which correspond to the case 1 of our analysis. Thus, most existing theoretical works on the bargaining over fertility outcomes are based on the situation in case 1. However, some evidences also identify the women’s larger ideal number of their children than that of men in both developed and developing countries. According to such empirical studies, this case can be found in the societies characterized by specific cultural factors rather than the universal factors including the pain of giving birth.Footnote 22 Since it could well capture some aspects of the real world, the other case also needs to be examined. As to the effects of a rise in the female wage rate on fertility, we have the following proposition.

Proposition 2

When women prefer a larger family size than their husbands, an increase in female wage rate raises the fertility rate if and only if

Proof

See Appendix A.□

To illustrate the result of Proposition 2 more simply, specifying the male parental utility function to be log-linear form, \(v_m \left( n \right)=\ln n\), enables us to rewrite Eq. 15 as follows:

From Eq. 16, the smaller per unit time for domestic childcare, the larger the difference between men and women’s fertility goals, the smaller the number of their children, and the larger the positive partial effect of the wage rate on women’s bargaining power, the more likely that a rise in female wage rate will increase fertility outcomes.

Intuitively, an increase in w again raises not only the opportunity cost of childcare but women’s expected labor income, providing them with an advantage over intra-household distribution. Therefore, when women want more children than men (a > 1), the sign of the total effect of a rise in w on the number of children in equilibrium depends on the relative magnitude of the negative effect due to a higher opportunity cost and the positive effect due to the decision making over fertility that better reflects women’s preferences. If the former effect is overwhelmed by the latter, the fertility outcome rises in spite of a higher opportunity cost of childrearing. This finding is not led by the traditional result of an income effect but through a rise in women’s bargaining power, since the increased fertility outcome cannot be achieved with a fixed level of bargaining power. This theoretical result implies that gender bargaining power is one of the factors that explain both a high fertility rate and a high level of women’s autonomy over decisions in the household, such as those observed in developed countries where the mothers’ burden of raising children began to be shared in many ways with their husbands.

4 Policy analysis

In this section, we discuss the policy implications of our model. Most developed countries are facing low fertility rates and thus the government’s aim at maintaining sustainable demographic structures (Ilmakunnas 1997; Cigno and Werding 2007). Following Apps and Rees (2004), we examine the effect of a revenue-neutral increase in subsidy for bought-in childcare financed by a reduction in child allowance so that we can compare the effects of two policies on the fertility outcome.

Consider an economy which is characterized by two stable steady-state equilibria (Fig. 2b). Now, assume that we are on point E 1 in Fig. 2b, where the fertility rate is low. The government collects the lump-sum tax for the purpose of running the family policies. Denote the policies by T, g S , and g T where T is the lump-sum tax levied on each household and g S and g T are the subsidy for bought-in childcare allocated per unit of good and child allowance received per child, respectively. For simplicity, we assume that the price of bought-in childcare is normalized to unity in the analysis below.

Introducing two policies implies that the cost minimization problem of childcare becomes

subject to Eq. 3. Since, under the assumption of CRS, the unit cost of having a child is constant regardless of the number of children, recalculating the cost minimization problem above allows us to reduce the budget constraint as follows:

where \(\widetilde{q}\left( {1-g_S ,w} \right)\) = \(\left( {1-g_S } \right)\widetilde{x}\left( {1-g_S ,w} \right)\) + \(w\widetilde{t}\left( {1-g_S ,w} \right),\widetilde{x}\left( {1-g_S ,w} \right)\), and \(\widetilde{t}\left( {1-g_S ,w} \right)\) represent the unit cost of having a child, market childcare per child, and maternal attention per child after policy implementation, respectively. Given the balance of power within a household, it maximizes its welfare function of Eq. 2, subject to Eq. 18, so that they derive their fertility outcomes as \(n=n\left( {\theta ;w,g_T ,g_S } \right)\). Since the marriages in society are homogenous, we can then derive the number of children and the level of woman’s bargaining power in the equilibrium by solving both \(n=n\left( {\theta ;w,g_T ,g_S } \right)\) and \(\theta =\theta \left( w\left({1-{\hat{t}n}} \right)/Y\right.=\psi \left( {n;w,Y,g_S } \right)\).

The government is providing economic support for households’ childrearing with g S and g T , financing them by lump-sum taxes. To focus on the policy effects without tax distortion, we have made the conventional assumption that they are financed by a lump-sum tax on the same household. The budget constraint is given, in household terms as

The government implements a policy shift with an exogenous change in g T so that they can balance their budget constraint by adjusting the level of g S .

We can then obtain the following proposition by using the total derivative of fertility with respect to g T .

Proposition 3

A revenue-neutral increase in the subsidy for bought-in childcare by a reduction in child allowance may reduce the fertility rate.

Proof

We can show that the total derivative of fertility with respect to g T is

where Δ < 0 is the marginal cost to the government of an increase in g S (see Appendix B). From \({\partial \psi } / {\partial g_S }>0\), due to the increase in women’s labor income by technical substitution into bought-in childcare, this expression depends on the difference between men and women’s preferences of family size.Footnote 23 From the concavity of v i (n), in the case of a < 1, Eq. 20 implies that the fertility rate falls with a reduction in g T .□

The intuition behind this result is as follows. While the child allowance will merely cut off the cost of having a child, the subsidies for bought-in childcare have a positive effect on the women’s empowerment as well as a negative one on the unit cost of a child. The subsidy for bought-in childcare triggers a technical substitution in childcare, leading to higher female labor income and, thus, an increase in women’s bargaining power in the economy. Regarding the latter effect, a subsidy decreases the cost of childrearing through a reduction in the price of bought-in childcare, so that the parents can then afford to have more children. Because child allowance and subsidies for bought-in childcare have the same effect on unit cost of a child as they offset each other, an increase in g S financed by reduction in g T makes the household decisions more favorable for women.

In the absence of the preference conflict between spouses (a = 1), the model in our model is essentially the same as the traditional analyses focusing on the household responses to changes in prices and income. Hence, a policy shift toward the subsidy has no effect on fertility outcomes. However, in the case that women’s desired family size is relatively small (a < 1), if the negative effect of bargaining power on fertility outcome is sufficiently large, the introduction of a subsidy may result in an unexpected negative effect on fertility rates. In other words, the introduction of a subsidy policy aiming at a higher fertility rate may itself accelerate the decline in childbirths.

As we can see from the discussion above, it is obvious that both the conflicting preferences and the gender bargaining power determine the effectiveness of the policies. From the viewpoint of the governmental target to boost the fertility rates, the former is preferable since the effect of child allowance on fertility is not affected by the bargaining effect, while the latter may end up in reducing fertility rates. If governments call for improvements in women’s autonomy in the decision making within their families in parallel with higher fertility outcomes, the coordination of these policies will be urgently needed.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we formulate a simple intra-household decision-making model over fertility outcomes, where its bargaining power depends not only on the relative prices of time of family members but also on the relevant social pressure on gender roles, taking the advantage of the tractability in the model of Basu (2006).

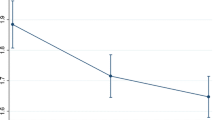

We develop a model to show the observed patterns of bargaining power and fertility, i.e., the economy with unempowered women and a high fertility rate, and that with empowered women and a low fertility rate. This type of multiple equilibria is likely to emerge when women prefer a small number of children compared to their husbands. This result partly corresponds to the evidence presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3 shows this simple relationship between the total fertility rates (TFR) of 2000–2005 and women’s say, namely, the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), using cross-sectional data based on the 2007–2008 Human Development Report (UNDP 2007). Apart from the different prices and other economic circumstances among these countries, we see low-GEM countries indicate high TFR while high-GEM countries do the opposite. More formal empirical evidence in support of this result can be found in Feyrer et al. (2008). They observed three phases in women’s statuses: the earliest phases of women’s economic position with the most domestic work followed by intermediate phase of improved female labor market opportunities with their household status lags. In the final phase, women commit more and more of their time to the labor market and the number of their children is the fewest.

Under the opposite but plausible assumption of parental preferences, the model also gives a potential explanation for the fact that a raise in female wage rates may cause the higher fertility rate despite the higher opportunity cost of having a child.Footnote 24 The results above are derived from the conflict in preferences and the feedback effect on the gender bargaining power due to the actual fertility outcomes of other couples in the society. This suggests that the effectiveness of family policy is determined not only by the economic situation but also by the intra-household decision process.

Although we have examined the policy effects on fertility, the extension to the analysis of optimal policy introducing the taxation on labor income may be a promising direction. This also relates to the debate between individual taxation and joint taxation for household since these policies can affect the economic relationships among family members.

Notes

Their specification of bargaining power relates to the traditional analysis of family bargaining where the bargaining positions are determined by individuals’ outside option in the case of breakdown in their negotiations. For an excellent survey on family bargaining, see Lundberg and Pollak (1996).

The author thanks an anonymous referee for his/her introduction of the literature.

Cigno (2012) showed that marital institution affects the couple’s choice whether to behave noncooperatively or cooperatively by specializing in either childcare or market work. Rasul (2008) also investigated the limited commitment problem of household and demonstrated that the absence of binding contract leads to inefficient fertility outcomes. In his study, however, since the women’s position is not characterized by her earnings, the negative effect of children on women’s labor supply is not explicitly considered.

In both theoretical and empirical studies, many authors have shown that most societies have traditionally incorporated fertility trends into their gender role norms and that these norms may damage women’s economic position (Folbre 1997; Fernandez et al. 2004; Munshi and Myaux 2006; Feyrer et al. 2008).

Many other existing evidences confirmed the heterogeneity in parental preferences of fertility outcomes (Mason and Taj 1987; Ngom 1997; Voas 2003). The family bargaining on fertility under these conflicting parental preferences is also observed in both developed and developing countries. Rasul (2008) found fertility bargaining using Malay and Malaysian Chinese micro-data while Hener (2010) confirmed that of German households.

Breakdown of negotiations due to heterogeneous preferences are beyond our scope. As an explanation of this breakdown, Manser and Brown (1980) and McElroy and Horney (1981) translated the threat-point in Nash bargaining as divorce. For the intra-family bargaining analysis with the threat-point of noncooperative outcome, see Lundberg and Pollak (1993).

Individual’s additional utility from the number of their children, v i (n), may differ between men and women taking into account the biological difference such as the women’s time devoted to pregnancy, giving birth, and the social norms or culture that impose on them other particular roles regarding childrearing.

This assumption is justified if Y > w under the model in which mother and father’s time for childcare are perfect substitution and family members can choose their time allocation between labor supply and childcare. However, under Y > w and as long as women’s time and men’s time are substitutable, even if we ease the assumption of perfect substitution, the main results of this paper are unaffected. From the fact that there is no country where the average female wage rate is as high as the average male wage rate even in OECD countries, we can assume women’s lower opportunity cost of their time than that of men (OECD Employment Outlook 2010).

Specific examples are the perinatal and lactation period.

Because the scale effect in childcare is sensitive to the timing of birth, Cigno and Pettini (2002) assume the possible situation in which the negative and positive effects offset each other so that they can simply assume constant returns to scale in production of childcare. This assumption is also employed in the analysis of family policies such as in Apps and Rees (2004).

The idea of the Pareto weights within a household was introduced by the studies on the collective model of Chiappori (1988, 1992). According to his studies, the distributional rule is affected by exogenous variables such as wages and marital institutions. The recent study of Basu (2006) succeeded in endogenizing the distributional rule, taking account of the feedback effect of household choices themselves on the power balance in the household. The effect of fertility choice, however, is not considered in his analysis. The fact that an increase in the wife’s income relative to her husband’s brings her more autonomy in household decision making is also supported in many empirical studies such as those of Browning et al. (1994), Hoddinott and Haddad (1995), and Lundberg et al. (1997). Zamora (2011) suggested that fertility choice affects the distributional rule, showing that the choice of female labor participation has a significant effect on the rule. Moreover, relative earning is also one of the components in the indicator of the degree of women’s economic autonomy used by the international institutions (e.g., gender empowerment measures in Human Development Report (UNDP 2007)).

Feyrer et al. (2008) pointed out that women’s status is affected not only by the common economic factors but also by the longstanding cultural and social ones. Regarding the point of the social factor in gender bargaining power, we assume that peer pressure reflecting the relevant norms shapes the behaviors of future parents. The empirical works such as those of Goldstein et al. (2003), Lutz et al. (2006), and Testa and Grilli (2006) showed the significant correlation between the actual fertility outcome and the young generations’ standards relating parental attitude.

See for example, Lundberg and Pollak (1993).

The classification into these two cases is reasonable from the empirical point of view since they are observed in both developed and developing countries. For example, Mason and Taj (1987) surveyed the existing empirical evidences of developing countries including the both cases and concluded that, on average, men’s demands for children are likely to be larger than those of their wives. We also examined the case of a = 1, the conventional common preference model, as a benchmark case in the previous version of this paper so as to show the well-known positive effect of a reduction in the price of bought-in childcare on fertility outcomes.

Ngom (1997) found evidence that men desire to have more children than women do in Ghana and Kenya. According to Westoff’s (2010) studies on ideal family sizes in developing countries, men report a larger ideal number of children on average in 32 out of 33 countries. As Fig. 1 indicates, this trend in reproductive preferences can also be seen in developed countries (Testa 2006). Based on these facts, Maitra (2004) has formulated a model in which women are more likely to bear the cost of having children.

The possible interpretation of the bargaining power function in Fig. 2b is as follows. If other couples have a single child on average, it reduces the wife’s time in market work. A young couple then anticipates that the wife would spend as much time for childcare as other wives do and, thus, women’s less expected labor income. Consequently, it leads to the lower bargaining power of young women, though its decline is relatively small. Once the other couples have more than a certain number of children, however, the young couple expects that much of the wife’s time will be occupied by childcare. As a result, the wife’s bargaining power drastically decreases. After this sharp decline in her power, the wife finally gives up the whole power within her households moderately because of other couples’ fertility choices. In this situation, the multiple equilibria in Fig. 2b are likely to emerge in the economy.

In the analysis of Iyigun and Walsh (2007), the woman’s strategic behavior of educational investment improves her utility in the case of a breakdown in the marital agreement, i.e., their bargaining power, and this behavior induces a declining fertility rate because of the higher opportunity cost of having and rearing children.

High fertility may reinforce the husband’s loyalty and economic support to the wife, who will then be more likely to avoid divorce and abandonment by her husband (Mernissi 1975). Furthermore, in some societies, women’s own value may be heightened by bearing numerous children (Blake 1965). These could be among the factors causing women to prefer a greater number of children. Similar relationships between parental preferences are also found in developed countries (Thomson et al. 1990; Testa 2006).

Since \({\partial \psi \left( {n;w,Y,g_S } \right)} / {\partial g_S }=-{\theta^ \prime wn} / Y\cdot {\partial \widetilde{t}} / {\partial g_S }\), \({\partial \widetilde{t}} / {\partial g_S <0}\) gives \({\partial \psi } / {\partial g_S }>0\).

References

Ahn N, Mira P (2002) A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. J Popul Econ 15:667–682

Andersson G (2000) The impact of labor-force participation on childbearing behaviour: pro-cyclical fertility in Sweden during the 1980s and the 1990s. Eur J Popul 16:293–333

Apps P, Rees R (2004) Fertility, taxation and family policy. Scand J Econ 106:745–763

Basu K (2006) Gender and say: a model of household behavior with endogenously determined balance of power. Econ J 116:558–580

Blake J (1965) Demographic science and the redirection of population policy. J Chron Dis 18:1181–1200

Browning M, Bourguignon F, Chiappori PA, Lechene V (1994) Income and outcomes: a structural model of intrahousehold allocation. J Polit Econ 102:1067–1096

Butz P, Ward P (1979) The emergence of countercyclical US fertility. Am Econ Rev 69:318–328

Chiappori PA (1988) Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56:63–89

Chiappori PA (1992) Collective labor supply and welfare. J Polit Econ 100:437–467

Cigno A (2008) A gender-neutral approach to gender issues. In: Bettio F, Verashchagina A (eds) Frontiers in the economics and gender. Routledge, London, pp 45–56

Cigno A (2012) Marriage as a commitment device. Rev Econ Household 10:193–213

Cigno A, Pettini A (2002) Taxing family size and subsidizing child-specific commodities? J Public Econ 84:75–90

Cigno A, Werding M (2007) Children and pensions, CESifo book series. The MIT, Massachusetts

Doepke M, Tertilt M (2009) Women’s liberation: what’s in it for men? Q J Econ 124:1541–1591

Engelhardt H, Kögel T, Prskawetz A (2004) Fertility and women’s employment reconsidered: a macro-level time-series analysis for developed countries, 1960–2000. Pop Stud-J Demog 58:109–120

Ermisch J (1989) Purchased child care, optimal family size and mother’s employment theory and econometric analysis. J Popul Econ 2:79–102

Eswaran M (2002) The empowerment of women, fertility, and child mortality: towards a theoretical analysis. J Popul Econ 15:433–454

Fernandez R (2010) Women’s rights and development. DRI Working Paper No 68, New York University

Fernandez R, Fogli A, Olivetti C (2004) Mothers and sons: preference formation and female labor force dynamics. Q J Econ 119:1249–1299

Feyrer J, Sacerdote B, Stern A (2008) Will the stork return to Europe and Japan? Understanding fertility within developed nations. J Econ Perspect 22:3–22

Folbre N (1997) Gender coalitions: extrafamily influences on intrafamily inequality. In: Haddad L, Hoddinott J, Alderman H (eds) Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries: models, methods, and policy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp 263–274

Goldstein J, Lutz W, Testa MR (2003) The emergence of sub-replacement family size ideals in Europe. Popul Res Policy Rev 22:479–496

Gustafsson S (1992) Separate taxation and married women’s labor supply: a comparison of West Germany and Sweden. J Popul Econ 5:61–85

Hener T (2010) Do couples bargain over fertility? Evidence based on child preference data. Working Paper, Ifo Institute for Economic Research, University of Munich

Hoddinott J, Haddad L (1995) Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford B Econ Stat 75:77–95

Hoem B (2000) Entry into motherhood in Sweden: the influence of economic factors on the rise and fall in fertility 1986–1997. Demogr Res 2

Ilmakunnas S (1997) Public policy and childcare choice. In: Persson I, Jonung C (eds) Economics of the family and family policies. Routledge, London, pp 178–193

Iyigun M, Walsh R (2007) Endogenous gender power, household labor supply and the demographic transition. J Dev Econ 82:138–155

Konrad KA, Lommerud KE (2000) The bargaining family revisited. Can J Econ 33:471–487

Lehrer EL (1996) Religion as a determinant of marital fertility. J Popul Econ 9:173–196

Lundberg S, Pollak RA (1993) Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. J Polit Econ 101:988–1010

Lundberg S, Pollak RA (1996) Bargaining and distribution in marriage. J Econ Perspect 10:139–158

Lundberg S, Pollak RA (2003) Efficiency in marriage. Rev Econ Household 1:153–167

Lundberg S, Pollak RA, Terence TJ (1997) Do husbands and wives pool their resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom child benefit. J Hum Resour 32:463–480

Lutz W, Skirbekk V, Testa M (2006) The low-fertility trap hypothesis: forces that may lead to further postponement and fewer births in Europe. Vienna Yearb Popul Res 4:167–192

Maitra P (2004) Parental bargaining, health inputs and child mortality in India. J Health Econ 23:259–291

Manser M, Brown M (1980) Marriage and household decision making: a bargaining analysis. Int Econ Rev 21:31–44

Mason K, Taj A (1987) Differences between women’s and men’s reproductive goals in developing countries. Popul Dev Rev 13:611–638

McElroy M, Horney MJ (1981) Nash-bargained household decisions: toward a generalization of the theory of demand. Int Econ Rev 22:333–349

Mernissi F (1975) Obstacles to family planning practice in urban Morocco. Stud Family Plann 6:418–425

Mincer J (1963) Market prices, opportunity costs, and income e?ects. In: Christ C et al (ed) Measurement in economics: studies in mathematical economics and econometrics in memory of Yehuda Grufeld. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 67–82

Munshi K, Myaux J (2006) Social norms and the fertility transition. J Dev Econ 80:1–38

Ngom V (1997) Men’s unmet need for family planning: implications for African fertility transitions. Stud Family Plann 28:192–202

OECD (2010) OECD employment outlook. Paris OECD

Rainer H (2008) Gender discrimination and efficiency in marriage: the bargaining family under scrutiny. J Popul Econ 21:305–329

Rasul I (2008) Household bargaining over fertility: theory and evidence from Malaysia. J Dev Econ 86:215–241

Testa M (2006) Childbearing preferences and family issues in Europe. Special Eurobarometer 253, 65: European Commission, Brussels

Testa M, Grilli L (2006) The influence of childbearing regional contexts on ideal family size in Europe. Population 61:109–138 (English edition)

Thomson E, Mcdonald E, Bumpass LL (1990) Fertility desires and fertility: hers, his, and theirs. Demography 27:579–588

United Nations Development Programme (2007) UNDP Human Development Report 2007/2008: fighting climate change: human solidarity in a divided world. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Vagstad S (2001) On private incentives to acquire household production skills. J Popul Econ 14:301–312

Vikat A (2004) Women’s labor force attachment and childbearing in Finland. Demogr Res Special Collection 3:177–212

Voas D (2003) Conflicting preferences: a reason fertility tends to be too high or too low. Popul Dev Rev 29:626–646

Westoff CF (2010) Desired number of children: 2000–2008. DHS Comparative Reports 25, Calverton: ICF Macro

World Bank (2012) World databank. http://databank.worldbank.org/ddp/home.do. Accessed 7 May 2012

Zamora B (2011) Does female participation affect the sharing rule? J Popul Econ 24:47–83

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor, Alessandro Cigno, and two referees of this journal for their detailed and constructive comments. I am also grateful to Hikaru Ogawa, Takanori Adachi, Makoto Hirazawa, Kazutoshi Miyazawa, Emiko Usui, Akira Yakita, and the participants of the 14th Labor Economics Conference and the workshop held at Nagoya University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Komura, M. Fertility and endogenous gender bargaining power. J Popul Econ 26, 943–961 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0460-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0460-6