Abstract

This paper provides evidence on the effect of welfare reform on fertility, focusing on UK reforms in 1999 that increased per-child spending by 50% in real terms. We use a difference-in-differences approach, exploiting the fact that the reforms were targeted at low-income households. The reforms were likely to differentially affect the fertility of women in couples and single women because of the opportunity cost effects of the welfare-to-work element. We find no increase in births among single women, but evidence to support an increase in births (by around 15%) among coupled women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There has been considerable interest in the effect of welfare on fertility. Much of the existing evidence comes from the USA where studies have typically exploited variation in programme generosity and timing of implementation across states to identify an effect. In general, the US evidence finds that more generous welfare is associated with increased births (see Moffitt 1998), although the results are sensitive to specification.

This paper presents new evidence from a set of reforms to benefits for families with children introduced in the UK in 1999. The two most important reforms (in terms of scale of increased support) were, first, the introduction of the Working Families’ Tax Credit (WFTC), similar in design to the US Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which increased the generosity of benefits for households with children where at least one parent worked 16 h a week or more,Footnote 1 and, second, increases in means-tested income support payments to workless families. These reforms would be expected to increase fertility through income and price effects. But the overall fertility effect of welfare reforms designed to improve work incentives, such as WFTC, is a priori ambiguous because of a potentially offsetting opportunity cost effect. We argue that the opportunity cost effect—and hence the overall effect on fertility— is likely to vary between women in couples and single women and that the pro-fertility effect of the reforms is likely to be stronger for women in couples; we find evidence for this being the case in practice.

The UK makes a good case study to study the effect of welfare reform on fertility because of the sheer scale of the reforms. Between 1999 and 2003, government spending per child on child-contingent cash transfers, payable tax credits and traditional tax allowances increased by 50% in real terms, a change that was unprecedented over the previous 30-year period (Adam and Brewer 2004). Most of the additional spending was targeted at low-income households. For the poorest one fifth of couples with children, the changes increased cash benefits received for the first child by an amount equivalent to 10% of net household income.

A number of studies have looked at the effects of the set of reforms on employment (see inter alia Gregg and Harkness 2003; Blundell et al. 2005; Francesconi and van der Klaauw 2007; Leigh 2007; Gregg et al. 2009), finding a significant increase in employment among lone parents, but little overall effect on the employment of women in couples.

The only previous study to consider fertility, Francesconi and van der Klaauw (2007), focused on lone mothers and found a (statistically insignificant) reduction in the probability of lone mothers having another child after the reforms. However, the fertility incentives of the reforms for this group are ambiguous because the improved work incentives offered by WFTC could cause a reduction in fertility by raising the opportunity cost of an additional child. The pro-fertility effect is likely to be stronger for women in couples.

Since the reforms were nationwide, we cannot follow the US studies in identifying the policy effect from variation across state and time. Instead, we exploit the fact that the reforms were targeted at low-income households and adopt the commonly used difference-in-differences (DD) approach (see Angrist and Krueger 1999). We look at the change in fertility before and after the reform for women who were affected by the reform and use the change in fertility over the same period for women unaffected by the reform to control for other (unobservable) time-varying effects that might otherwise have affected births (such as any “Millennium” effect). While this methodology cannot precisely disentangle the effects of the individual policies, it can yield powerful and straightforward evidence on the overall impact of the set of reforms that were introduced in 1999 (Ellwood 2000). Because household income is likely to be affected by the reform, we use the education of the woman (and her partner) to define a treatment group and a comparison group.

In the following section, we summarise the previous literature in this area. Section 3 describes the UK reforms in further detail, and Section 4 discusses the possible effect of the reforms on the incentives to have children. Sections 5 and 6 describe our empirical strategy and the data we use. Section 7 presents the results of regression analysis, and Section 8 presents a number of robustness checks. Section 9 offers some conclusions.

2 Previous research

According to a basic economic model of fertility (see Becker 1991), more generous government support for children would tend to raise the desired number of children through both a positive income effectFootnote 2 and a positive own price effect. There is a large US literature that tries to test this prediction with regard to welfare programmes, much of it focusing on Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC; see Moffitt 1998, for an overview). Identification in studies of AFDC typically relies on variation in generosity across states, and although there is clearly a positive statistically significant correlation between welfare generosity and fertility, the results are sensitive to methodology and, in particular, the inclusion of state fixed effects and trends (see Hoynes 1997).

Baughman and Dickert-Conlin (2003) examined the effect of EITC on fertility. Focusing on first births and on women with less than college education, who are likely to be more affected by the reforms, they exploit variation in state EITC payments to identify an effect. They control for state fixed effects and time-varying policy and economic variables, but not state trends. Overall, they find that more generous EITC benefits have a negative effect on first births, although this is statistically insignificant. But they find a positive effect for married women and a larger effect for non-Whites. In Section 4 below, we argue that positive fertility effects are more likely for women in couples because they are less likely to experience an offsetting opportunity cost effect and we show that this is also the case in the UK.

A number of other papers provide evidence that total fertility is responsive to government policy. Whittington et al. (1990) use time series data from 1913 to 1984 to show that changes in the personal tax exemption for dependents in the USA correlate with the number of children born, with an implied elasticity of between 0.127 and 0.248, while Whittington (1992) finds the same relationship using micro-data from the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics, with an estimated elasticity in the range 0.23–1.31. For the UK, Ermisch (1988) finds that the magnitude of (universal) child benefit payments has an effect both on timing of entry into motherhood and on family size through third and fourth births. The simulated effect of doubling the real value of child benefit on family size is of similar (absolute) magnitude to the effect of doubling house prices.

A number of studies have looked at the effect of explicitly pro-natalist policies. Laroque and Salanie (2005) examined the effect of the Allocation Parentale d’Education (APE) introduced in France in 1994. In a discrete choice framework, they relate employment and fertility choices to the financial incentives implied by the tax and benefit system, and they find evidence of a small effect of the APE on childbearing, higher for first births, in spite of the fact that the benefit was paid in the event of higher order births; Laroque and Salanie (2008) generalise this and find evidence that first and third births in France are responsive to financial incentives. Milligan (2005) found a positive effect of the Allowance for Newborn Children introduced in Quebec in 1998.

3 The UK reforms

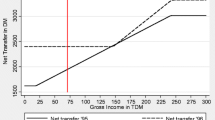

Our focus in this paper is on a set of reforms in the UK that increased the generosity of government support to families, initiated by the incoming Labour government in 1997 and introduced in 1999. The combined effect of the reforms is illustrated in Fig. 1 which shows the increase in child-contingent benefits (broken down by benefit type) as a proportion of (pre-reform) net household income, by deciles of income (adjusted for household composition), for couples with one child and for couples with two or more children.Footnote 3 This highlights the relative importance of each of the elements of the reforms, showing that WFTC was the single most important element. Also, it shows that the effects of the changes were concentrated among poorer households. For those in the bottom fifth of the income distribution, the rise in child-contingent support meant increases in net income of around 10% for those with one child and over 12% for those with two or more children.

Turning to each of the elements of the reforms,Footnote 4 the WFTC was introduced in October 1999 to provide improved work incentives for families with children. It replaced an existing, small, in-work cash support programme known as Family Credit (FC), but as Fig. 1 shows, WFTC was much more generous than FC. Both WFTC and FC paid money to recipients working for at least 16 h/week, tapered away with householdFootnote 5 earnings (plus some other forms of income) above a threshold. Unlike EITC, WFTC did not have a phase-in portion; it was also substantially more generous that EITC at PPP rates (see Brewer 2001). The number of households with children in receipt of tax credits rose from 0.8M in August 1999, just before WFTC was introduced, to 1.3M in November 2002, out of a total of 7.0M families claiming universal child benefit. Just under one half of WFTC recipients (46%) were in a couple.Footnote 6

The second element was an increase in the generosity of means-tested benefits (income support) for workless families, also introduced in October 1999. Overall, this reform was less important than the introduction of WFTC, except for families in the bottom income decile.

Finally, child benefit, a universal cash benefit available to all families with children, saw a small increase in the amount paid in respect of the first child. Thus, even households in the top income decile saw an increase in child-contingent benefits, but the size of the increase as a percentage of household income was negligible.

4 The impact on fertility

Considering a simple economic model of fertility, there are a number of possible channels through which the package of reforms outlined above might impact on the desired number of children. First, eligible families will experience a positive income effect which, if children are a normal good, will tend to increase demand. Second, more generous means-tested benefits and tax credits will reduce income volatility,Footnote 7 and this will also tend to increase the demand for children (see Fraser 2001). Third, the overall increase in child-contingent benefitsFootnote 8 will lower the own price of an additional child for eligible women, increasing demand. The package of reforms is therefore expected to have positive impacts on fertility through income, insurance and price effects.

However, one of the intentions behind WFTC was to improve work incentives. Assuming that a birth is associated with a reduction in labour market participation, welfare-to-work programmes such as WFTC may have a negative effect on fertility for women who are incentivised to increase their attachment to the labour market. For women who are induced to move into, or increase, employment by the introduction of WFTC (potentially anyone below the minimum threshold for WFTC eligibility), the effect of the reforms is to increase the opportunity cost of an additional child, reducing demand for children.

However, the opportunity cost effect is not uniform for all women. For women on the taper of the WFTC schedule, there will be a fall in net wages that will actually reduce the opportunity cost of an additional child, increasing the demand for children. In summary, WFTC, may have an ambiguous impact on fertility through the employment (or opportunity cost) effect. Crucially, this employment effect is likely to vary between different sorts of (potential) mothers.

For lone mothers whose eligibility for WFTC is assessed at the individual level, the labour market participation effects of WFTC are unambiguously positive. The credit provides an incentive for non-working lone mothers to move into work. Those working more than 16 h prior to the reform may have an incentive to reduce their hours both because their incomes are higher and because of the negative substitution effect created by the taper, but the 16-h condition in WFTC ensures that labour supply does not fall to zero.

For women in couples who are the secondary earner (as is typically the case), WFTC may actually reduce participation. WFTC has the same income and substitution effects as for lone mothers, but a coupled woman may reduce her hours below 16 or leave the labour market altogether if the family will continue to be eligible for WFTC on the basis of her partner’s participation.

These different employment effects are reflected in a number of studies that have looked at the impact of the 1999 reforms (summarised in Table 1). Most adopt a DD approach and therefore capture the effect of the package of reforms, although two of the studies—Blundell et al. (2002) and Brewer et al. (2006)—focus just on WFTC (see also Brewer and Browne 2006, for a review). The evidence supports a sizeable increase in employment among lone mothers, but no change, or a reduction, in employment among women in couples.

Given these employment effects and in particular the increase in employment among lone parents, we would expect the positive fertility effects to be stronger for women in couples than for single women and we explore this in our empirical analysis.

5 Empirical strategy

We employ the commonly used DD approach in order to identify the effect of the reforms. We compare the change in births after the reform among the group of women who were affected (the treatment group) with the change in births over the same period of a naturally occurring comparison group. Identification in the DD model relies heavily on the so-called common trends assumption;Footnote 9 the treatment and comparison groups do not have to have the same mean outcomes in the pre-reform period (this is taken care of by the within-group differencing), but births must be subject to the same trends in the absence of the reforms. We explicitly test for differential trends in the analysis below.

We exploit the fact that the reforms were targeted at low-income households to define a treatment group who were affected by the reforms and a comparison group who were not. While household income is likely to be strongly correlated with the reforms’ impact, it is also likely to be endogenous and affected by the impact of the reforms on both employment and fertility. Instead, we use education as a time-invariant proxy for income to define treatment and comparison groups. In the short term at least, we can be confident that education choices are unaffected by the reforms.

Our analysis focuses, first, on all women and, secondly, on women in couples for whom we can incorporate additional information on partner’s education to get a tighter definition of treatment and comparison groups. In our all-women sample, the treatment group includes women who left full-time education at the minimum school leaving age,Footnote 10 while the comparison group is women who left full-time education aged 19 years or more. In our sample of women in couples, the treatment group includes women who both left full-time education at the minimum school leaving age and have a partner who left at this age. Similarly, the comparison group includes women who both left full-time education at 19+ and who have a partner who left full-time education at this age.

Compared to using income or earnings, the potential disadvantage of using education is that it is less strongly correlated with the impact of the reform. There are some people with a (low) high level of education whose earnings nevertheless do (not) qualify them for tax credits or means-tested benefits. Table 2 summarises mean child-contingent benefits received before and after the reform by the treatment and comparison groups. It illustrates the extent to which our education splits pick up the differential impact of the reforms across the two groups and shows that there are much larger increases in child-contingent benefits among the treatment group (equal to more than £900 a year) than among the comparison group. As expected, incorporating additional information on partner’s education produces a clearer differentiation between treatment and comparison groups.Footnote 11

As already noted, the DD methodology cannot precisely disentangle individual policy effects (such as separating the effect of WFTC from that of changes to income support). Our estimate is therefore of the combined effect of the set of reforms introduced in 1999. It will also include the effect of any other reforms introduced at the same time that affected the fertility of the treatment group (and not the comparison group). In fact, a number of changes were made to maternity rights and child-care provision that may have affected fertility, including extensions to maternity leave and increases in free nursery provision.Footnote 12 In principle, all women were affected by these reforms, but in practice, the impact may have been greater for women in the low education group if they previously had less generous maternity provisions in their employment and were less able to afford childcare. If so, then our DD estimate will also include the differential effect of these other reforms. We would argue, however, that the effects of these reforms are likely to be small compared to the impact of WFTC and the changes to income support.

We define the outcome of interest as the probability of having a birth during the previous year and compare the changes in these birth probabilities before and after the reform for the treatment and comparison groups. This means that we cannot fully distinguish whether an observed effect is due to changes in the total number of births or changes in timing, although we attempt to do so by looking at the age at first birth (see Section 8).

A final issue relates to the definition of the “before” and “after” periods in determining the effect of the reform. WFTC was announced in March 1998 and introduced in October 1999. Assuming no announcement effects—as if the reform came as complete surprise in October 1999—the reform would first have affected births from August 2000. We therefore include women interviewed between 1st April 1995 and 30th June 2000 in the “before” sampleFootnote 13 and women interviewed between 1st August 2001 and 31st December 2003 in the “after” sample.Footnote 14 For women interviewed between 1st July 2000 and 31st July 2001, the introduction of the reform (plus 9 months) occurs in the middle of the 12-month period prior to their interview and so they are omitted from the analysis.

What if there is an effect arising from announcement? This could increase births in the immediate before period if women respond to the announcement of the reforms rather than (or as well as) their implementation. This is not implausible. The Labour government took office in 1997 promising big increases in financial support for low-income families, and the reforms were announced in March 1998. So long as the promised increase in benefits is credible, then the loss arising from the gap between announcement and implementation would be relatively small compared to the expected increase in benefits over the child’s lifetime. Alternatively, after announcement, women could decide to delay childbearing until after the reforms were implemented, which would tend to decrease births in the immediate before period (an effect similar to “Ashenfelter’s dip”, see Ashenfelter 1978). In either case, failing to take account of a possible announcement effect would bias our estimate of the effect of the reforms. We therefore test the sensitivity of our results to possible announcement effects by trimming the before sample at 31st December 1998 (9 months after the reform was announced).

6 Data

Our analysis uses data from successive waves of the Family Resources Survey (FRS) from 1995/1996 until 2003/2004, supplemented with data from the Family Expenditure Survey (FES) going further back to financial year 1990/1991 to allow us to test explicitly for differential trends in the treatment and comparison groups. Both the FRS and FES are large, repeated cross-section datasets collecting a wide range of socioeconomic and demographic information on, respectively, over 7,000 and 20,000 households each year.Footnote 15 The combined sample yields over 800 births each year, with interview dates spread roughly equally across the year. While potentially attractive as a panel, the British Household Panel Survey (used by Francesconi and van der Klaauw 2007) has fewer than 150 births a year. We focus on women aged 20–45 since at younger ages many women are still in full-time education.

The FES and FRS do not explicitly collect information on births or women’s fertility histories. But we derive the probability that a woman had a birth in the previous 12 months from children’s date of birthFootnote 16 and the date of interview after allocating all children in the household to their natural mothers on the basis of information on household composition. Using this approach (the so-called own child method, see Murphy and Berrington 1993), we also determine the number and ages of the children in the household 12 months before interview. Birth probabilities estimated by this approach are potentially subject to measurement error due to infant mortality and household reconstitution. However, low rates of mortality and the fact that the overwhelming majority of children stay with their natural mother in the event of family breakup reduce the effect of these factors in practice.Footnote 17

As a check on the validity of our data, we compare an estimate of period total fertilityFootnote 18 derived from the FES/FRS with the official estimate of period total fertility derived by the Office for National Statistics from registration data. As shown in Fig. 3 in the “Appendix”, our estimate derived from FES/FRS data picks up the main trends in fertility over the period—declining fertility over much of the period, reversed from 2001. If anything, the upward trend is under-stated in the FES/FRS, although the downward trend is slightly over-stated. Our derived measure consistently lies below the official measure, which may reflect the narrower age range in our FES/FRS sub-sample.

7 Regression results

The outcome of interest is a binary variable equal to one if the woman had a birth in the previous 12 months and equal to zero otherwise (Birth). The basic DD specification (1) includes a binary variable Low equal to one if the individual belongs to the low-education treatment group, a binary variable Post equal to one in the post-reform period and an interaction term Low × Post, which captures the difference in the change in birth probability after the reform for the treatment group (compared to the comparison group). The coefficient β 1 therefore captures the effect of the reform (the treatment effect).

X it is a vector of characteristics which are assumed to affect fertility. These include a cubic in the woman’s age (at the start of the 12-month period), interacted with education; the number of children in the household (at the start of the 12-month period), interacted with the woman’s age and with the woman’s age and education and with the age of the youngest child; and region and housing tenure. We also include controls for the woman’s ethnicity and that of her partner where appropriate.Footnote 19

We estimate Eq. 1 using a linear probability model for ease of interpretation of the coefficients.Footnote 20 In the first instance, we use data from 1995 to 2003, allowing us to control for ethnicity. In the next section, we exploit the longer pre-period, incorporating data from 1990, to test explicitly for differential trends. We also use data from the pre-period to test for and reject the presence of within education-group clustering and serial correlation among the residuals. Either of these would pose a potentially serious problem for DD estimates and would invalidate our estimated standard errors (see Angrist and Pischke 2009; Moulton 1990; Bertrand et al. 2004). With independent error terms, we can apply standard inference procedures to the DD estimates.

Our results, reported in Table 3,Footnote 21 show a statistically insignificant increase in births among all women (column 1). When we split the sample into single women and couples, we find a bigger increase among women in couples, which is statistically significant at the 10% level (columns 2 and 3). This is similar to the findings in Baughman and Dickert-Conlin (2003) who find a positive effect of EITC on births only for married women. This is consistent with the fact that the potentially negative opportunity cost effect on fertility is likely to be stronger for single women. Focusing on women in couples, we can define the treatment and comparison groups more tightly using additional evidence on partner’s education. The estimated coefficient increases in magnitude and becomes statistically significant at the 5% level (column 4).

7.1 Allowing for heterogeneous effects—over time

Focusing on women in couples, Fig. 2 shows the estimated effects (and associated confidence intervals) from including interaction terms for the treatment group with year dummies for each year before and after the reform. There are consistently positive differentials for the treatment group after the reform; the biggest effect (with a p value of 0.056) is in the first year after the reform. There is no consistent pattern in the pre-reform period. While there is a positive differential in one of the pre-reform years, it is smaller in magnitude than all but one of the post-reform differentials. In the next section, we carry out a number of additional robustness checks, controlling for non-linear trends and the effect of other macro-variables.

7.2 Allowing for heterogeneous effects—birth order

A number of previous studies have found fertility responses to vary by birth order. Laroque and Salanie (2008), for example, find a stronger effect of the French Allocation Parentale d’Education on first and third births. The fact that second births are less responsive to financial incentives may reflect underlying strong preferences for having two children. Berrington (2004) shows that almost all women with one child would like a second, and this decision may be less susceptible to financial incentives compared to the decision whether—or when—to have a first child and whether to have more than two children. In addition, as shown in Fig. 1, the marginal increases in benefits are larger for the first child than for subsequent children.

We therefore interact our indicator of the treatment effect with an indicator for whether or not the woman had children at the beginning of the 12-month period and with indicators for the number of children. The results, reported in Table 4, support previous findings of a stronger effect for first births and also for third births. However, the differences by number of previous births are not statistically significant.Footnote 22

8 Further analysis

Our regression results indicate a fairly sizeable fertility response to the reforms. The probability of birth among the treatment group in the pre-reform period was 0.089, so a 1.3 percentage point rise as in Table 3, column 4 would imply an increase of around 15%. In this section, we assess, first, whether this result is robust and, second, whether it is plausible.

8.1 Robustness checks

Identifying the effect of the reforms using a DD approach relies crucially on successfully controlling for everything else that might affect the fertility of the treatment group in the absence of the reform. Including the comparison group should pick up the effect of common factors that affect all women—such as any Millennium effect. But the DD approach is not valid if births among the two groups are subject to different trends. Using additional data from a longer pre-period (going back to 1990), we therefore explicitly test for differential trends across the two groups. Column 1 of Table 5 shows the basic result using the longer period of data,Footnote 23 while columns 2 and 3 show that neither linear nor quadratic differential trend terms are statistically significant.Footnote 24 Including the trend terms increases the standard error making it harder to identify a statistically significant effect of the reform, but the magnitude of the coefficient representing the effect of the reforms is reasonably robust.

Finally, column 4 adopts an alternative approach to exploring differential time effects by including a number of macro-controls that may affect fertility and allowing their effect to vary across the two groups. These include the lag of log real house prices at the regional level and lagged male and female regional unemployment rates. We also include the (lag of the) 25th and 75th percentile of the female and male wage distributions, matched to the treatment and comparison groups respectively.Footnote 25 Including these variables increases the magnitude of the estimated effect.

8.2 Plausibility

While our results suggest a sizeable response to the reforms, the magnitude of our estimated effect is not out of line with previous studies. For example, Milligan (2005) estimated that the probability of birth increased by 17% for a Canadian $1,000 increase in total support via the Allowance for Newborn Children; in the UK, the mean increase in annual benefits for the low-education group was greater than this at around £900 per year (greater still for some families within this group)—and the increase applied potentially for each year of the child’s life. Milligan found that at least some of the effect was due to a change in the timing of births, and there is some evidence that this is also the case here. Table 6 summarises the results of estimating a DD specification of age at first birth. The coefficient is negative, but not statistically significant.

Finally, we present some additional, supporting evidence for the effect of the reforms on births from another part of the “fertility decision tree”. Levine (2002, p. 1) argues that “consistent findings [from different stages of this decision tree] provide stronger evidence of a causal link [from policy to fertility] than focusing on just one stage.” We look at use of contraception using data from the 1998 and 2002 UK General Household Surveys. We define a binary variable equal to one if the woman reports that she is currently not using contraception either because she is already pregnant or because she wants to get pregnant. We estimate a linear probability model using the same basic DD specification (column 1). The results, reported in Table 7, are fully consistent with the findings for births. There was an increase in the proportion of women in the low education group reporting that they were not using contraception because they were trying to get—or already were—pregnant. This increase is statistically significant at the 10% level. Further analysis by the number of births the woman has already had (column 2) shows that, as with actual births, the increases were greatest for women who had previously had no and two births, although as before the differences between the effects are not statistically significant.

9 Conclusions

The reforms that took place in the UK in 1999 make an excellent case study for addressing the question of whether fertility responds to financial incentives, not least because of the scale of the increases. Examining evidence on the response to these reforms, this paper makes a number of contributions to the existing literature on the effect of welfare on fertility.

First, we make the argument that the fertility effects of welfare reforms to improve work incentives are potentially ambiguous, and we suggest that the pro-fertility effect is likely to be stronger for women in couples. We provide evidence to support this, consistent with earlier findings from the USA.

Second, we find evidence of an increase in births coinciding with the reforms among the group most affected, adding to the existing literature that fertility responds to financial incentives. Our finding seems entirely plausible—the magnitude of the response is not out of line with previous estimates and we provide supporting evidence from a separate survey that contraception use also changes around the time of the reforms. Finally, we also confirm previous findings that effects vary by birth order; we find a bigger response for first births than for subsequent births.

Notes

Alternatively, it has been argued that higher income is associated with demand for increased quality of children, implying a possible reduction in quantity demanded.

The scale and pattern of the changes are similar for lone parent families.

The assessment was made on the basis of the couple’s joint earnings even in the case of cohabiting couples.

There was no attempt to present these reforms as revenue neutral: annual expenditure on FC/WFTC almost doubled between 1998–1999 and 2000–2001, from £2.68 billion to £4.81 billion in constant 2002 prices, with a further increase by 2002 to £6.46 billion.

Gregg et al. (2009) show that an important effect of WFTC was to mitigate the negative impact of moving into lone parenthood on employment and income.

Including the increase in support with payments for childcare.

The minimum school leaving age was raised from 14 to 15 from 1944 and from 15 to 16 from 1973.

We have replicated the analysis using a split based on household income and an interaction of household income and education. These alternative definitions of treatment and comparison groups produce stronger results, available on request.

See Hills and Waldfogel (2004) for a summary.

We choose end of June rather than end of July to allow for premature births.

Further reforms were made to the system of child-contingent benefits from this time.

It is not possible to do the analysis using official birth statistics because they do not contain information on education or income and, for unmarried or re-married women, on true birth parity.

Where this is missing, we randomly allocate a date of birth given the age of the child and the date of interview. This is the case for all births in the FES sample and 16% of births in the FRS sample.

Another issue that affects information on the number and ages of existing children at the start of the 12-month period (but not information on births during that period) is that older women may have had children who have now left home. We test the sensitivity of our results to restricting our sample to women aged 37 and under for whom this does not appear to be a problem.

This is measured as the total number of children a woman would have over her (reproductive) lifetime if she experienced the age-specific birth rates in a particular year.

The ethnicity information is fairly crude; we include indicators if the woman or her partner is Black, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani or other (non-White). Many of the recent births to women born outside the UK are to recent White immigrants from the eight EU accession countries (including Poland, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia). However, this wave of immigration occurred after the end of our period of analysis (beginning in May 2004).

The average estimated marginal effects from a probit regression are very similar, and these results are available on request.

One implication of this is that the reforms had an effect on the fertility decisions of households who were not (yet) receiving the benefits. However, McKay (2000, 2001) shows that there was a fairly high level of awareness of the new benefits even among those who were not receiving it, which may have come about as a result of the extensive television advertising and/or through word-of-mouth.

This differs to the specification in Table 3, column 4 both because of the longer period (1990–2003 compared to 1995–2003) and because there are no controls for ethnicity. The effect of excluding the ethnicity variables in the 1995–2003 sample is to reduce the coefficient from 0.0130 (0.0066) to 0.0120 (0.0066).

An alternative way of showing that there are no differential trends would be to test for placebo reforms in the pre-reform period. The effects of these placebo reforms—tested for each year of the pre-reform period—are not statistically significant.

Wages, house prices and unemployment are identified by Ermisch (1988) as important determinants of fertility.

References

Adam S and BrewerM(2004) Supporting families: the financial costs and benefits of children since 1975. The Policy Press, Bristol

Angrist JD, Krueger AB (1999) Empirical strategies in labor economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 1277–1365

Angrist JD, Pischke J (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Ashenfelter OC (1978) Estimating the effect of training programs on earnings. Rev Econ Stat 60:47–57

Baughman R, Dickert-Conlin S (2003) Did expanding the EITC promote motherhood? Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 93(2):247–250

Becker GS (1991) A treatise on the family. Enlarged edition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Berrington A (2004) Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Popul Trends 117:9–19

Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S (2004) How much should we trust difference-in-differences? Q J Econ 119(1):249–275

Blundell R, Costa-Dias M (2002) Alternative approaches to evaluation in empirical economics. Portuguese Econ J 1(2):91–115

Blundell R, Brewer M, Shepard A (2005) Evaluating the labour market impact of the working families’ tax credit using difference in differences. HM revenue and customs working paper 4

Blundell R, Duncan A, McCrae J, Meghir C (2000) The labour market impact of the Working Family Tax Credit. Fisc Stud 21(1):75–103

Brewer M (2001) Comparing in-work benefits and the reward to work for families with children in the US and the UK. Fisc Stud 22(1): 41–77

Brewer M (2003) The new tax credits. IFS Briefing Note BN35. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Brewer M, Browne J (2006) The effect of the working families’ tax credit on labour market participation. IFS briefing note 69. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Brewer M, Duncan A, Shephard A, Suarez MJ (2006) Did working families’ tax credit work? The impact of in-work support on labour supply in Great Britain. Labour Econ 13(6):699–720

Ellwood DT (2000) The impact of the earned income tax credit and social policy reforms on work, marriage, and living arrangements. Natl Tax J 53(4):1063–1106

Ermisch J (1988) Econometric analysis of birth rate dynamics in Britain. J Hum Resour 23(4):563–576

Francesconi M, van der Klaauw W (2007) The socioeconomic consequences of in-work benefit reform for British lone mothers. J Hum Resour 42(1):1–31

Fraser CD (2001) Income risk, the tax-benefit system and the demand for children. Economica 68(269):105–125

Gregg P, Harkness S (2003) Welfare reform and lone parents employment in the UK. CMPO working paper series 03/072, University of Bristol

Gregg P, Harkness S, Smith S (2009) Welfare reform and lone parents. Econ J 119(535):F38–F65

Hills J, Waldfogel J (2004) A ‘Third Way’ in welfare reform: what are the lessons for the US? J Policy Anal Manage 23(4):765–788

Hoynes H (1997) Does welfare play any role in female headship decisions? J Public Econ 65(1997):89–118

Laroque G, Salanie B (2005) Fertility and financial incentives in France. CESifo Econ Stud 50(3):423–450

Laroque G, Salanie B (2008) Does fertility respond to financial incentives? CESifo working paper 2339

Leigh A (2007) Earned income tax credits and labor supply: evidence from a British Natural Experiment. Natl Tax J 60(2):205–224

Levine PB (2002) The impact of social policy and economic activity throughout the fertility decision tree. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 9021

McKay S (2000) Low/moderate-income families in Britain: work, working families’ tax credit and childcare in 2000. Department for Work and Pensions research report 161, London

McKay S (2001) Working families’ tax credit in 2001. Department for Work and Pensions research report 205, London

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Moffitt R (1998) The effect of welfare on marriage and fertility. In: Moffitt R (ed) Welfare, the family and reproductive behaviour: research perspectives. National Academy, Washington, pp 50–97

Moulton B (1990) An illustration of a pitfall in estimating the effects of aggregate variables on micro units. Rev Econ Stat 72(2):334–338

Murphy M, Berrington A (1993) Constructing period parity progression ratios from household survey data. In: Bhrolchain MN (ed) New perspectives on fertility in Britain. HMSO, London pp 17–32

Whittington LA (1992) Taxes and the family: the impact of the tax exemption for dependents on marital fertility. Demography 29(2):215–226

Whittington LA, Alm J, Peters HE (1990) Fertility and the personal exemption: implicit pronatalist policy in the United States. Am Econ Rev 80(3):545–556

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the ESRC under its programme, Understanding Population Trends and Processes (RES-163-25-0018), and through the Centre for Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy at IFS. Material from the Family Expenditure Survey, the Family Resources Survey and the General Household Survey was made available by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) through the UK Data Archive and has been used by permission of the Controller of HMSO. The authors would like to thank Richard Blundell, Hilary Hoynes, Karl Scholz, Frank Windmeijer and an anonymous referee as well as seminar participants at CMPO, IFS, ONS and the Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Junsen Zhang

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brewer, M., Ratcliffe, A. & dSmith, S. Does welfare reform affect fertility? Evidence from the UK. J Popul Econ 25, 245–266 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0332-x