Abstract

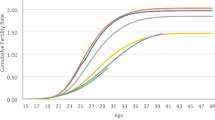

This chapter provides a comparative analysis of fertility and family transformations and policy responses in Austria and the Czech Republic, two neighboring countries in Central Europe that were until 1989 separated by the “Iron Curtain” dividing the two competing political blocs in Europe. The comparison is stimulated by the geographic proximity and shared history and culture of these two countries in the past and their gradual economic and social convergence in the most recent quarter century. During this recent period, both societies became surprisingly similar in their fertility and family patterns and main family policy trends. Fertility in both countries is relatively low, but not extremely low when compared with the countries of Southern Europe or East Asia. The period total fertility rate recently converged to 1.5 births per woman, and cohort fertility rates for the women born in the mid-1970s are projected at 1.65 (Austria) and 1.8 (Czech Republic) births per woman. Austrian fertility rates have been remarkably stable since the 1980s, while in the Czech Republic fertility imploded during the 1990s, following the political regime change, and then partly recovered in the 2000s. In both countries, childbearing has rapidly shifted to later ages and increasingly has taken place outside marriage, with more than one-half of first births now born to cohabiting couples and single mothers. Czech women are much less likely to remain childless, possibly due to the persistently strong normative support to parenthood in the country. Family policies, relatively generous in terms of government expenditures, were until recently dominated by a view that mothers should stay at home for an extended period with their children, making the return to employment difficult for women. The combination of extensive parental leave, negative attitudes toward working mothers with children below age three, limited availability of public childcare for these children, and in the Czech Republic, limited availability of part-time employment affects childbearing decisions, especially among highly educated women. Recent policy adjustments have made parental leave more flexible in both countries and, in the case of Austria, have supported a gradual expansion of public childcare and a stronger involvement of men in childrearing.

Research presented in this paper was partly supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC Grant agreement n° 284238 (EURREP). An earlier, expanded version of this paper has been published as Vienna Institute of Demography (VID) Working Paper 2/2015 and can be accessed at http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/download/WP2015_02.pdf. Throughout this chapter, the author refers to this working paper (Sobotka 2015) for additional details.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Own estimate based on the gross fertility rate published by the League of Nations (1943).

- 2.

Women’s employment during the state-socialist period was strongly encouraged for two reasons—economic, in order to cope with the shortage of labor in an inefficient state-directed economy and ideological, whereby everyone had a duty to contribute to society by his or her work. The “right and duty to work” was explicitly stated in the constitutions of 1948 and 1960. In addition, “avoidance of work” and “parasitism” (i.e., living without working or making a living from illegal activities) were punishable by law (Havelková 2009). In practice, this law was not always strictly enforced, and some women could stay at home after completing their maternity leave. However, women’s employment was also considered a financial necessity for most families.

- 3.

This sum almost equals the average annual net income of a childless employed person in 2012, which amounted to CZK 233,602 (US$9083) (OECD 2015a).

- 4.

Press release and additional information available at http://www.bmfj.gv.at/ministerin/Aktuelles/Themen/Familienfreundlichkeitsmonitor.html.

- 5.

Despite the ongoing expansion of university education, Austrian data show that having children while studying remains rare. In 2002–2012, around 1400 children were born annually to mothers who were students, which is less than 2 % of all births.

References

Arbeiterkammer [Austrian Chamber of Labor]. (2014). Parental leave schemes. http://media.arbeiterkammer.at/ooe/berufundfamilie/2014_Infoblatt_Kinderbetreuungsgeld_Varianten.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2014.

Basten, S., Sobotka, T., & Zeman, K. (2014). Future fertility in low-fertility countries. In W. Lutz, W. P. Butz, & K. C. Samir (Eds.), World population and human capital in the 21st century (pp. 39–146). Oxfiord: Oxford University Press.

Beaujouan, É., Sobotka, T., Brzozowska, Z., & Neels, K. (2013). Education and sex differences in intended family size in Europe, 1990s and 2000s. Paper presented at the Conference on Changing Families and Fertility Choices, Oslo, June 6–7, 2013.

Berghammer, C. (2014). The return of the male breadwinner model? Educational effects on parents’ work arrangements in Austria, 1980–2009. Work, Employment & Society, 28(4), 611–632.

Boeckmann, I., Misra, J., & Budig, M. J. (2014). Cultural and institutional factors shaping mothers’ employment and working hours in postindustrial countries. Social Forces, advanced online access,. doi:10.1093/sf/sou119.

Bongaarts, J., & Feeney, G. (2006). The quantum and tempo of life cycle events. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 2006, 115–151.

Bongaarts, J., & Sobotka, T. (2012). A demographic explanation for the recent rise in European fertility. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 83–120.

Buber-Ennser, I., Neuwirth, N., & Testa, N. R. (Eds.). (2014). Families in Austria 2009–13: Descriptive findings on partnerships, fertility intentions, childbearing, and childrearing. Vienna: Vienna Institute for Demography/Wittgenstein Centre and Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

CFE (Cohort Fertility and Education) Database. (2014). Data on completed fertility of women in Austria and the Czech Republic by level of education in the Cohort Fertility and Education Database. http://www.cfe-database.org. Accessed October 8, 2014.

Chaloupková, J., & Šalamounová, P. (2004). Postoje k manželství, rodičovství a k rolím v rodině v České republice a v Evropě. [Attitudes to marriage, parenthood, and family roles in the Czech Republic and in Europe]. Sociologické Studie, 2004/7.

Council of Europe. (2006). Recent demographic developments in Europe, 2005. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

CSO (Czech Statistical Office). (2014). Annual time series of the key indicators of population and vital statistics in the Czech Republic, 1785–2013. http://www.czso.cz/csu/redakce.nsf/i/obyvatelstvo_hu. Accessed April 10, 2015.

CVVM (Centrum pro Výzkum Veřejného Mínění). (2014). Postoje českých občanů k manželství a rodině—prosinec 2013. [Attitudes of Czech citizens to marriage and family—December 2013]. Press release ov140120. Prague: The Public Opinion Research Centre. http://cvvm.soc.cas.cz/en/relations-attitudes/attitudes-of-czech-citizens-to-marriage-and-family-December-2013. Accessed April 10, 2015.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The incomplete revolution: Adapting to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eurostat. (2014a). Data on live births by age of mother, first marriages by age of bride, population by age and marital status, fertility rates by age, net migration, and population balance. Eurostat online statistics database. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Accessed June, August, and October 2014.

Eurostat. (2014b). Eurostat population statistics: Foreign-born and non-national population. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/. Accessed October 24, 2014.

Festy, P. (1979). La fécondité des pays occidentaux de 1870 à 1970. Travaux et Documents No. 85. Paris: INED, PUF.

Geist, C., & Cohen, P. N. (2011). Headed toward equality? Housework change in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(4), 832–844.

GGS (Generations and Gender Survey). (2009). Familienentwicklung in Österreich. Erste Ergebnisse des Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) 2008/09. [Family developments in Austria. First results of the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) 2008/09]. Vienna: Vienna Institute for Demography and Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

Goldstein, J. R., Kreyenfeld, M., Jasilioniene, A., & Örsal, D. D. K. (2013). Fertility reactions to the ‘Great Recession’ in Europe. Demographic Research, 29(4), 85–104.

Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. V. Glass & D. E. C. Eversley (Eds.), Population in history: Essays in historical demography (pp. 101–143). Chicago: Aldine.

Halman, L., & Draulans, V. (2006). How secular is Europe? The British Journal of Sociology, 57(2), 263–288.

Hamachers-Zuba, U., Lehner, E., & Tschipan, C. (2009). Partnerschaft, Familie, und Geschlechterverhältnisse in Österreich [Partnership, family, and gender relations in Austria]. In C. Friesl, R. Polak, & U. Hamachers-Zuba (Eds.), Die Österreicher-innen. Wertewandel 1990–2008 (pp. 87–141). Vienna: Czernin.

Havelková, B. (2009). Pracovní právo [Labor law]. In M. Bobek, P. Molek, & V. Šimíček (Eds.), Komunistické právo v Československu. Kapitoly z dějin bezpráví. Mezinárodní politologický ústav (pp. 478–512). Brno: Masarykova univerzita. Available at www.komunistickepravo.cz

Herrnböck, J. (2012). Väterkarenz: Streit über Zahlen [Peternal leave: A fight over the numbers]. Der Standard, 20, November 2012. http://derstandard.at/1353206775448/Papamonat-Streit-ueber-Zahlen. Accessed October 21, 2014.

Human Fertility Collection. (2014). Period fertility rates by age and birth order for Austria, 1952–1983. Estimated by T. Sobotka and A. Šťastná. http://www.fertilitydata.org. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Human Fertility Database. (2014). Period fertility data for Austria and the Czech Republic and cohort fertility data for Sweden. http://www.humanfertility.org. Accessed August 2014.

Kantorová, V. (2004). Education and entry into motherhood: The Czech Republic during the state socialism and the transition period (1970–1997). Demographic Research, 3(10, Special Collection), 245–274.

Kocourková, J. (2002). Leave arrangements and childcare services in Central Europe: Policies and practices before and after transition. Community, Work, and Family, 5(3), 301–318.

Kohoutová, I., & Nývlt, O. (2014). Rodina a statistika [Family and statistics]. Press conference, 9 April 2014, Prague: Czech Statistical Office. http://www.czso.cz/csu/tz.nsf/i/prezentace_z_tk_rodina_a_statistika/$File/csu_tk_rodina_prezentace.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

Kytir, J. (2005). Demographische Strukturen und trends 2001–2004 [Demographic structure and trends 2001–2004]. Statistische Nachrichten, 2005(9), 776–789.

Lalive, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2009). How does parental leave affect fertility and return to work? Evidence from two natural experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1363–1402.

League of Nations. (1943). Statistical year-book of the League of Nations, 1941–42. Geneva: League of Nations, Economic Intelligence Service. http://digital.library.northwestern.edu/league/stat.html#1941. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Lee, R., Mason, A., et al. (2014). Is low fertility really a problem? Population aging, dependency, and consumption. Science, 346(6206), 229–234.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Lux, M., & Sunega, P. (2010). Private rental housing in the Czech Republic: Growth and…? Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 46(3), 349–373.

Miranda, V. (2011). Cooking, caring, and volunteering: Unpaid work around the world. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers No. 116. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Nývlt, O. (2014a). Perspektivy mladé generace při zakládání rodiny [Perspectives of young adults for family formation]. Press conference, 7 May 2014, Prague: Czech Statistical Office. http://www.czso.cz/csu/tz.nsf/i/prezentace_z_tk_perspektivy_mlade_generace_pri_zakladani_rodiny/$File/csu_tk_mladi_prezentace.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

Nývlt, O. (2014b). Sladění rodinného a pracovního života [Reconciliation of family and work life]. Presentation to the Czech Demographic Society, 19 Feb 2014. https://www.natur.cuni.cz/geografie/demografie-a-geodemografie/ceska-demograficka-spolecnost/diskusni-vecery-1/prezentace-ke-stazeni/2014-02-19-sladeni-rodinneho-a-pracovniho-zivota/view. Accessed October 8, 2014.

Nývlt, O., & Šustová, Š. (2014). Rodinná soužití s dětmi v České republice z pohledu výběrových šetření v domácnostech. [Family arrangements with children in the Czech Republic from the perspective of household surveys]. Demografie, 56(3), 203–218.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2011). Doing better for families. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264098732-en. Accessed April 20, 2015

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2014a). OECD family database. http://www.oecd.org/social/soc/oecdfamilydatabase.htm. Accessed October 2014.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2014b). Society at a glance 2014: The crisis and its aftermath. OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/els/societyataglance.htm. Accessed April 29, 2015.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2015a). Statistics on social protection and wellbeing: Benefits, taxes, and wages–net incomes. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FIXINCLSA. Accessed February 5, 2015.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2015b). OECD better life index: Housing indicators. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/housing/. Accessed February 6, 2015.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2015c). Education at a glance 2014. http://www.oecd.org/edu/education-at-a-glance-2014-indicators-by-chapter.htm. Accessed February 7, 2015.

OIF (Austrian Institute for Family Studies). (2014). Familien in Zahlen (FiZ). Vienna: Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

ONS (Office for National Statistics). (2013). Cohort fertility, England and Wales, 2012. Data released 5 Dec 2013. London: Office for National Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/fertility-analysis/cohort-fertility-england-and-wales/2012/index.html. Accessed August 20, 2014.

Pakosta, P. (2009). Proč chceme děti: hodnota dítěte a preferovaný počet dětí v České republice [Why we want children: The value of children and the preferred number of children in the Czech Republic]. Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 45(5), 899–934.

Paloncyová, J., & Šťastná, A. (2012). Sňatek a rozchod jako dva možné způsoby ukončení nesezdaného soužití [Marriage and breakup as two possible paths away from cohabitation]. Demografie, 54(3), 214–232.

Prioux, F. (1993). The ups and downs of marriage in Austria. Population: An English Selection, 5, 153–182.

Prskawetz, A., Sobotka, T., Buber, I., Gisser, R., & Engelhardt, H. (2008). Austria: Persistent low fertility since the mid-1980s. Demographic Research, 7(19–12), 293–360.

Rabušic, L., & Chromková-Manea, B. E. (2007). Jednodětnost v českých rodinách. Kdo jsou ti, kdo mají nebo plánují pouze jedno dítě [One-child families in the Czech Republic. Who are the people who have or plan to have just one child?]. Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 43(4), 699–719.

Rabušic, L., & Chromková-Manea, B. E. (2012). Postoje, hodnoty a demografické chování v České a Slovenské republice v období transformace (1991–2008) [Attitudes, values, and demographic behavior in the Czech and Slovak Republics in the period of transformation (1991–2008)]. Data a výzkum—SDA Info, 6(1), 27–49.

Reinprecht, C. (2007). Social housing in Austria. In C. Whitehead & K.J. Scanlon (Eds.), Social housing in Europe (pp. 35–43). London: London School of Economics and Political Sciences. http://vbn.aau.dk/files/13671493/SocialHousingInEurope.pdf. Accessed April 29, 2015.

RHS (Reproductive Health Survey). (1995). 1993 Czech Republic reproductive health survey: Final report. Czech Statistical Office, Factum, WHO, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/czech-republic-reproductive-health-survey-1993. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Rille-Pfeiffer, C., & Kapella, O. (2012). Evaluierungsstudie Kinderbetreuungsgeld: Einkommensabhängige und pauschale Bezugsvariante 12+2 Monate [Evaluation study of leave allowances: Income-dependent and flat rate variant of 12+2 months]. Forschungsbericht No. 9–2012. Vienna: Austrian Institute for Family Studies.

Saxonberg, S., & Szelewa, D. (2007). The continuing legacy of the Communist legacy? The development of family policies in Poland and the Czech Republic. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State, and Society, 14(3), 351–379.

Sirovátka, T., & Bartáková, H. (2008). Harmonizace rodiny a zaměstnání v České republice a role sociální politiky [Harmonizing work and family in the Czech Republic and the role of social policy]. In T. Sirovátka & O. Hora (Eds.), Rodina, děti a zaměstnání v české společnosti. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Social Science.

Sobotka, T. (2009). Sub-replacement fertility intentions in Austria. European Journal of Population, 25(4), 387–412.

Sobotka, T. (2011). Fertility in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989: Collapse and gradual recovery. Historical Social Research, 36(2), 246–296.

Sobotka, T. (2015). Low fertility in Austria and the Czech Republic: Gradual policy adjustments. VID Working Papers 2/2015. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography.

Sobotka, T., Zeman, K., & Kantorová, V. (2003). Demographic shifts in the Czech Republic after 1989: A second demographic transition view. European Journal of Population, 19(3), 249–277.

Sobotka, T., Šťastná, A., Zeman, K., Hamplová, D., & Kantorová, V. (2008). Czech Republic: A rapid transformation of fertility and family behaviour. Demographic Research, 19(14–Special Collection), 403–454.

Sobotka, T., Skirbekk, V., & Philipov, D. (2011). Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review, 37(2), 267–306.

Šťastná, A. (2007). Druhé dítě v rodině–preference a hodnotové orientace českých žen. [Second child in the family: The preferences and values of Czech Women]. Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review, 43(4), 721–746.

Šťastná, A., & Sobotka, T. (2009). Changing parental leave and shifts in second- and third-birth rates in Austria. VID Working Papers 7/2009. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography.

Statistics Austria. (2014a). Childcare statistics. http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/bildung_und_kultur/formales_bildungswesen/kindertagesheime_kinderbetreuung/index.html. Accessed October 22, 2014.

Statistics Austria. (2014b). Demographische Indikatoren—erweiterte Zeitreihen ab 1961 für Österreich. [Demographic indicators—expanded time series for Austria from 1961]. Vienna: Statistics Austria. http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/bevoelkerung/demographische_indikatoren/index.html. Accessed August 6, 2014.

Thévenon, O. (2011). Family policies in OECD Countries: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 57–87.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). (2013). TransMonEE 2013 Database. UNICEF Regional Office for CEE/CIS. Released June 2013. http://www.transmonee.org/. Accessed August 2013.

Van Bavel, J., Jansen, M., & Wijckmans, B. (2012). Has divorce become a pro-natal force in Europe at the turn of the 21st century? Population Research and Policy Review, 31(5), 751–775.

VID (Vienna Institute of Demography). (2014). European demographic data sheet. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography and IIASA/Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital. http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/datasheet/DS2014/DS2014_index.shtml. Accessed April 29, 2015.

Wilson, C., Sobotka, T., Williamson, L., & Boyle, P. (2013). Migration and intergenerational replacement in Europe. Population and Development Review, 39(1), 131–157.

Wynnyczuk, V., & Uzel, R. (1999). Czech and Slovak Republic. In H. P. David (Ed.), From abortion to contraception: A resource to public policies and reproductive behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the present (pp. 91–119). Westport: Greenwood Press.

Zeman, K., Sobotka, T., Gisser, R., Winkler-Dworak, M., & Lutz, W. (2011). Geburtenbarometer Vienna: Analysing fertility convergence between Vienna and Austria. VID Working Paper 07/2011. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography.

Zeman, K., Sobotka, T., Gisser, R., & Winkler-Dworak, M. (2014). Geburtenbarometer 2013. Vienna: Wittengenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital and Vienna Institute of Demography/Austrian Academy of Sciences. http://www.oeaw.ac.at/vid/barometer/downloads/Geburtenbarometer_Ergebnis_2013.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sobotka, T. (2016). The European Middle Way? Low Fertility, Family Change, and Gradual Policy Adjustments in Austria and the Czech Republic. In: Rindfuss, R., Choe, M. (eds) Low Fertility, Institutions, and their Policies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32997-0_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32997-0_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-32995-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-32997-0

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)