Abstract

Purpose

There is a shortage of organ donors in Canada. The number of potential organ donors that are not referred to organ procurement organizations in Canada is unknown.

Methods

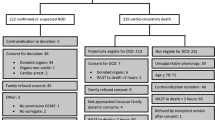

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all deaths in ICUs and emergency rooms not referred to the Human Organ Procurement and Exchange Program in four hospitals between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2010. The primary outcome was the number of normal and expanded criteria heart-beating donors and circulatory death (DCD) donors.

Results

Of 2,931 deaths, 64 patients were identified as having a high probability for progression to heart-beating donation (Glasgow Coma Score of 3 and three or more absent brainstem reflexes) and 130 patients were assessed for possible DCD donation. The number of potential abdominal and lung heart-beating donors ranged from 3.2 to 7.5 and 0.5 to 2.7 per million population. The number of potential DCD abdominal and lung donors ranged from 3.9 to 6.5 and 2.7 to 4.3 per million population. Potential heart-beating abdominal (p = 0.04) and lung (p = 0.06) donors increased after legislation mandating donation discussion. Non-pupillary brainstem reflexes were documented in fewer than 60 % of records. Life-sustaining treatment was withdrawn in 19 of 46 (41.3 %) cardiac arrest patients not requiring high doses of vasoactive drugs within 24 h.

Conclusion

The number of heart-beating or DCD organ donors represented by missed referrals may represent up to 7.5 donors per million population. Improved documentation of brainstem reflexes and encouraging referral of patients suffering cardiac arrest to ICU specialists may improve donor numbers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, the number of organ donors has not met the increasing demands for organs. In 2010, 4,529 patients were waiting for an organ transplant in Canada and 247 patients died while on the transplant recipient waiting list [1, 2]. From a public health perspective, approaches to improve organ donation have included presumed consent legislation, requesting by highly trained personnel, attending to specific relatives’ needs within the ICU, and public awareness of organ donation [3–6]. It is recognized that organ donation rates vary by country and are subject to temporal trends in the rates of cerebrovascular disease and traumatic brain injury while rates of death from stroke in Canada have declined by over 28 % within the 10 years preceding 2004 [7]. Previous descriptions of the missed potential for organ donation have, in part, been restricted to patients within intensive care units (ICUs) and dying from specific neurological diagnoses, with no published data from Canadian sources [8, 9].

In this retrospective cohort study, we determined the number of potential liver, kidney, and lung organ donors dying in ICUs and emergency rooms (ERs) over a 3-year period and that were not referred to the Human Organ Procurement and Exchange (HOPE) Program of Northern Alberta. We also determined the effect of implementing a provincial law mandating the documentation of organ and tissue donation discussions on the medical record on potential donor rates.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective chart review of all deaths within ICUs and ERs at the four largest hospitals in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2010. Northern Alberta is serviced by five major intensive care centers in Edmonton and one outside of Edmonton. An organizational algorithm of air and ground ambulance directs all major trauma, neurosurgical, neurological, and interventional cardiology services in Northern Alberta to two major centers included in this review. On 1 August 2009 the Human Tissue and Organ Donation Act was proclaimed by the government of Alberta which required a medical practitioner who determined that a person has died to “consider and document in the patient record the medical suitability of the deceased person’s tissues or organs for transplantation” [10].

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Board of the University of Alberta and Covenant Health.

Data collection

We defined non-referred patients as those dying within the ICUs and ERs who were not referred to the HOPE program and selected patients suffering from subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, intracerebral hemorrhage, stroke, pharmacological overdose, and asphyxia as well as those with anoxic encephalopathy from cardiac arrest and other cerebral catastrophes. In 2010 after the passing of the provincial legislation, we expanded our selection criteria to include all patients who had been referred to the HOPE program but did not proceed to brain death or did not proceed to cardiac death within 1 h of withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (WLST). The majority of these patients died from cardiac arrest. We excluded patients not 18–80 years of age, those with HIV, multisystem organ failure, metastatic cancer, degenerative neurological disorders, and those who had refractory hypotension despite high doses of vasoactive drugs. All non-referred patients were verified against a database which included all converted organ donors and referred but non-consented or medically unsuitable organ donors.

From the medical records, we included the patient’s age, primary etiology of death, neurological examination, neurosurgical procedures, requirement for vasoactive drugs, the site of the patient’s death as well as referral to and acceptance of the medical examiner. A high dose of vasoactive drugs was defined as requiring at least 20 μcg/min of norepinephrine or two or more vasoactive drugs. Our province required all deaths resulting from non-natural causes to be referred to the medical examiner for further investigation after death. Spontaneous respirations were deemed to be absent if the respiratory rate of the patient was not greater than the set respiratory rate on the mechanical ventilator prior to the WLST. We also included whether a family member was present or contacted at the time of death and whether a discussion regarding organ donation was documented. To determine the suitability for organ donation, we included the patient’s creatinine, bilirubin, and PaO2/FIO2 values nearest to death as well the patient’s comorbidities and, for potential circulatory death (DCD) donors, the time from WLST to the recording of asystole which was used to define death.

Outcome measures

Heart-beating donors

We identified potential organ donors using two independent assumptions. The first assumption defined each patient for their potential for proceeding to heart-beating donation (brain death) as patients having a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 3 out of a possible 15, and three or more absent brainstem reflexes (pupils, corneals, oculocephalic, oculovestibular, gag, or cough). Patients who did not have a GCS recorded or did not have documentation of at least three cranial nerve reflexes were not included as potential heart-beating donors. On the basis of previous studies, we expected 47.5 % of patients meeting these criteria to proceed to brain death and to become heart-beating donors [11, 12]. Expanded criteria liver or kidney (abdominal organ) donors were defined as those who had two or more of the following characteristics: age greater than 60 years, high vasoactive drug requirement (norepinephrine at least 20 μcg/min, or two or more vasoactive drugs), a history of hypertension, previous or current cerebrovascular disease, or at least 4 days in the ICU prior to death [13–15]. Normal criteria liver or kidney donors were defined as subjects not meeting the criteria for expanded criteria donation. We then defined potential normal heart-beating lung donors as those meeting the aforementioned neurological criteria with an age less than 55 years and a PaO2/FIO2 ratio of at least 300. Expanded criteria lung donors were defined as those no older than 70 years of age with a PaO2/FIO2 ratio of at least 250 and not meeting the criteria for normal lung donors [16, 17].

Donation after circulatory death (non-heart beating donors)

The second assumption evaluated each non-referred patient as a potential DCD donor, irrespective of neurological examination. We only included patients who did not meet all of our institutional requirements for brain death and who were extubated prior to the determination of death. We defined potential DCD kidney donors as those with age no greater than 60 years with creatinine less than 150 μcmol/L and who developed asystole within 120 min from extubation, and potential DCD liver donors as those with age no greater than 60 years with bilirubin less than 50 μcmol/L and who developed asystole within 60 min from extubation. Potential DCD lung donors were defined as those with age no greater than 70 years with a PaO2/FIO2 ratio of at least 300 and who developed asystole within 120 min from extubation. Patients with known hepatitis B or C infection were considered as potential heart-beating or DCD donors [13–19]. The adjudication process for abdominal organs was performed by an abdominal organ transplant surgeon (SA) and a hepatologist (CK), and that for lung donor suitability by a cardiac surgeon (GS) and cardiac intensive care specialist (DT). We also analyzed univariable associations between the absence of corneal and cough reflexes, absence of or extensor motor response, PaO2/FIO2 ratio of less than 200, high vasoactive drug requirements, and death within the emergency room (vs. ICU) and dying within 60 min of extubation. The first four of these parameters have undergone calibration and discrimination testing in recent studies [20–22].

Statistical analysis

We presented descriptive data as counts and percentages, means and standard deviations, and medians and interquartile ranges. We analyzed univariable associations between variables using the Pearson χ2 test, two-sided Fisher exact test, and logistic regression. We calculated potential organ donor rates per million population and incident rate ratios (IRR) using census estimates of the Northern Alberta population and assuming a Poisson distribution [23]. All analyses were performed using STATA 10 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA, 2008).

Results

Patient population

Of 2,931 medical records reviewed over the 3-year period, 227 (7.7 %) patients were defined as non-referred patients. The mean age was 61 years and 65 % were males. Over 3 years, 89 (39.2 %) of the subjects died of a cardiac arrest, 37 (16.3 %) died of an intracerebral hemorrhage, and 31 (13.7 %) died of traumatic brain injury, representing the three most common diagnoses. There was an increase in the number of cardiac arrests in 2010. Both the population mean bilirubin level of 25.0 (sd 34.0) μcmol/L and the mean creatinine level of 141 (sd 113.4) μcmol/L were elevated, with a reduced mean PaO2/FIO2 ratio of 246.6. Characteristics by year are outlined in Table 1.

Neurological examination

Collectively over 3 years, the median GCS was 3 and spontaneous respirations were absent in 37–48 % of patients. Although documentation of the pupillary reflexes was present in the majority of records, the documentation of corneal reflexes and the remaining brainstem reflexes was present in less than 60 and 50 % of records, respectively. The proportion of subjects who had at least three brainstem reflexes examined prior to withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy ranged from 41.5 % in 2009 to 57.6 % in 2010. Likewise, the percentage of subject who had a GCS of 3 and at least three absent brainstem reflexes ranged from 23.1 % in 2009 to 34.3 % in 2010 with no significant increase over the years (p = 0.19) (Table 2).

Characteristics of death

Over the 3-year period, 136 patients (59.9 %) died in an ICU, 75 patients (33.0 %) died in an ER, and 16 patients (7.1 %) died in a medical or surgical cardiovascular ICU. The attending physicians had referred 124 patients (54.6 %) to a medical examiner and 93 (41.0 %) of these patients were accepted for review. The family was available for discussion in over 90 % of the deaths and the documentation of organ donation discussion rose from 7.9 % in 2008 to 26.3 % in 2010 (p < 0.01). One hundred and thirty (57.2 %) of all patients did not meet criteria for brain death and were extubated prior to death. The mean time from WLST to death was 30.6 min (IQR 15.3–163.8 min) with 80 (61.5 %) patients dying within 1 h after WLST and an additional 15 (11.5 %) patients dying between 1 and 2 h after WLST. Of the 89 patients dying after a cardiac arrest, 42 (47.2 %) subjects required high doses of vasoactive drugs and 47 (52.8 %) had WLST within 24 h of the cardiac arrest. Significantly more cardiac arrest patients, 27 of 43 (62.8 %), had WLST within 24 h if they required high doses of vasoactive drugs as compared to 19 of 46 (41.3 %) not requiring high doses of vasoactive drugs (p = 0.03) (Table S1 in the electronic supplementary material).

Potential organ donation outcomes

Of the 114 (50.2 %) patients with at least three brainstem reflexes having been examined, 74 had three or more absent brainstem reflexes irrespective of their GCS, and 64 patients met the criteria for GCS of 3 and three or more absent brainstem reflexes and were adjudicated suitable for heart-beating donation. Collectively over 3 years, livers only could be procured from 13 (20.3 %) patients, kidneys from 2 (3.1 %) patients, and both liver and kidneys from 42 (65.6 %) patients. Lung procurement was possible in 18 (28.1 %) of 64 patients. Assuming 47.5 % of these patients would develop brain death, this would translate into 6 (9.4 %) liver-only donors, 1 (1.6 %) kidney-only donor, 20 (31.3 %) kidney and liver donors, and 9 (14.1 %) lung donors. Over the 3-year period this represents between 3.3 and 7.5 heart-beating abdominal organ donors and between 0.5 and 2.7 heart-beating lung donors per million population. A statistically significant increase in the incidence of heart-beating abdominal organs (IRR 2.28, 95 % CI 1.05–4.92, p = 0.04) and a trend to increasing heart-beating lung donors (IRR 2.44, 95 % CI 0.96–6.18, p = 0.06) was identified when comparing the rate in 2010 to the combined 2008 and 2009 rate (Table S2 in the electronic supplementary material).

Of the 227 non-referred patients assessed for possible DCD donation over 3 years, the number of abdominal organ donors dying within 60 min of WLST ranged from 4 (6.3) to 10 (15.4 %) and those dying from 60 to 120 min after WLST ranged from 7 (11.1) to 11 (11.1 %) patients. Potential DCD lung donors dying within 60 min of WLST ranged from 5 (7.7 %) to 7 (11.1 %) patients. This represented an additional 3.9 to 6.5 DCD abdominal organ donors (dying within 120 min) and a potential addition of 2.7–4.3 DCD lung donors per million population. No statistically significant difference in DCD donor incidence rates between 2010 and the combined 2008 and 2009 rate was found (Table S3 in the electronic supplementary material).

Univariable analysis demonstrated that absent corneal reflexes (OR 4.93, 95 % CI 1.77–13.73), absent cough reflex (OR 7.50, 95 % CI 1.61–34.95), absent or extensor motor response (OR 3.25, 95 % CI 1.33–7.91), and death in the ER (OR 3.21, 95 % CI 1.44–7.14) were significantly associated with death within 60 min of WLST. A weaker association was noted for a PaO2/FIO2 ratio less than 200 (OR 2.27, 95 % CI 0.98–5.26) and high vasoactive drug requirements (OR 2.88, 95 % CI 0.90–9.16). Seventeen patients had data available on all six variables; therefore, no inference could be made with multivariable analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

We found that heart-beating abdominal organ donation rates could improve between 3.3 and 7.6 and lung donation rates could improve between 0.8 and 2.5 per million population through referral of potential organ donors not currently referred to our organization. Similarly, DCD abdominal organ donation rates could improve between 3.9 and 6.5 and lung donation rates between 2.7 and 4.3 per million population. We noted a significant increase in incidence rates of both non-referred abdominal and lung heart-beating donors, but not DCD donors, in the year after the proclamation of legislation which mandated the documentation of donation discussions. We also noted significant associations between specific neurological reflexes as well as having died in the emergency room and death within 60 min of WLST. Contrary to Canadian recommendations, many patients suffering from cardiac arrest underwent WLST within 24 h of the cardiac arrest [24]. However, such withdrawal within 24 h may have been motivated by cardiac decompensation, or by the patient’s prior wish to forego further life-sustaining treatments.

The major strength of this study was the ability to ascertain all deaths within the ICUs and ERs and the accurate estimates of a population within a publically funded health system. The limitations of this study were that relevant comorbidities may not have been documented and we could not ascertain the suitability for heart donation given the lack of echocardiography. Some patients within the ERs and ICUs of smaller communities may not have been referred, and both neurological examination and discussions regarding organ and tissue donation may have occurred but may not have been documented. The estimate of potential organ donors may be conservative given that less than 60 % of patients had three or more brainstem reflexes or a FOUR Score performed [12].

Between 2008 and 2010 organs from 72 donors were procured and consent for organ donation was refused in 79 potential donors in Northern Alberta. This represented an average donation rate and consent refusal rate of 13.0 and 14.2 per million population. Our consent refusal rates represented at least double the number of potential non-referred organ donors. Although “collaborative requesting” has not been demonstrated to increase consent rates in one randomized trial, more effort and experience must be gained by physicians in discussions on non-cognitive issues (e.g., “maintenance of the donor body’s integrity” and “medical mistrust”) related to organ donation [4, 25]. The motivation to refer potential organ donors also depends on physicians’ preferences for allocating ICU beds, and on cultural variances in WLST practices [26–28]. Maintaining objectivity in the decision-making process used in WLST is important as previous studies have noted significant and subjective variability in this process in ICU, neurosurgical, and neurological patients [29–33].

A previous audit of deaths in 12 hospitals in Australia demonstrated that their maximal potential organ donor rate was 30 per million population and that half of the patients had treatment withdrawn in the ER with half being withdrawn in the ICU. This contrasts with our study where only 24–45 % of patients underwent withdrawal in the ER in any given year [9]. In a retrospective review of deaths in a neuro-ICU in Rotterdam, 54 % of patients suffering from traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or intracranial hemorrhage and having a GCS of 3 or 4 with two or more absent brainstem reflexes were deemed to have been potentially missed organ donors with the most common reasons for no donation being family refusal and the physician not considering organ donation [8]. Our rates of family refusal and missed referrals are higher than those in this study likely because of the inclusion of all ICUs and ERs in the population. Our findings are also consistent with a recent UK study indicating that obtaining family consent was the largest obstacle to donation in the UK [34]. Moreover, our findings of the absence of corneal, cough, and motor reflexes predicting death within 60 min of WLST were consistent with the previously proposed DCD-N score [20–22]. However, we also found a strong association between WLST in the ER and death within 60 min. This has not been previously described and may be related to death in the ER being a surrogate for poorer overall prognosis motivating a decision to limit treatment earlier.

Conclusions

Our findings have significant implications for policy improvement in organ donation. Attention must be paid to document a thorough examination of brainstem reflexes and refer these patients, along with cardiac arrest patients, to critical care specialists. This would improve survival prognostication, neurological care of potential survivors, and potentially increase the number organ donors. More effort should be made to educate physicians and nurses in recognizing non-cognitive factors that influence consent to donate. Finally, in the circumstances of potential DCD donation, previously described models predicting death within 60 min of WLST appear to have utility.

Abbreviations

- DCD:

-

Donation after circulatory death

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Score

- HOPE:

-

Human Organ Procurement and Exchange

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IRR:

-

Incidence rate ratio

- WLST:

-

Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment

References

Oz MC, Kherani AR, Rowe A, Roels L, Crandall C, Tomatis L, Young JB (2003) How to improve organ donation: results of the ISHLT/FACT poll. J Heart Lung Transpl 22:389–410

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2010) E-statistics report on transplant, waiting list and donor statistics (2010) http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/en/document/types+of+care/specialized+services/organ+replacements/report_stats2010. Accessed 1 May 2013

Abadie A, Gay S (2006) The impact of presumed consent legislation on cadaveric organ donation: a cross-country study. J Health Econ 25:599–620

The ACRE Trail Collaborators (2009) Effect of “collaborative requesting” on consent rate for organ donation: randomised controlled trial (ACRE trial). BMJ 339:b3911. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3911

Simpkin AL, Robertson LC, Barber VS, Young JD (2009) Modifiable factors influencing relatives’ decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ 338:b991

Salim A, Malinoski D, Schulman D, Desai C, Navarro S, Ley EJ (2010) The combination of an online organ and tissue registry with a public education campaign can increase the number of organs available for transplantation. J Trauma 69:451–454

Tu JV, Nardi L, Fang J, Liu J, Khalid L, Johansen H, Team CCOR (2009) National trends in rates of death and hospital admissions related to acute myocardial infarction, heart failure and stroke, 1994–2004. CMAJ 180:E118–E125

Kompanje EJ, Bakker J, Slieker FJ, Ijzermans JN, Maas AI (2006) Organ donations and unused potential donations in traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage. Intensive Care Med 32:217–222

Opdam HI, Silvester W (2004) Identifying the potential organ donor: an audit of hospital deaths. Intensive Care Med 30:1390–1397

Province of Alberta (2009) Human tissue and organ donatio act. Alberta Queen’s Printer, Edmonton, Alberta. http://www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/acts/h14p5.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2013

de Groot YJ, Jansen NE, Bakker J, Kuiper MA, Aerdts S, Maas AI, Wijdicks EF, van Leiden HA, Hoitsma AJ, Kremer BH, Kompanje EJ (2010) Imminent brain death: point of departure for potential heart-beating organ donor recognition. Intensive Care Med 36:1488–1494

de Groot YJ, Wijdicks EF, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, Lingsma HF, Ijzermans JN, Kompanje EJ (2011) Donor conversion rates depend on the assessment tools used in the evaluation of potential organ donors. Intensive Care Med 37:665–670

Ojo AO (2005) Expanded criteria donors: process and outcomes. Semin Dial 18:463–468

Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, Greenstein SM, Merion RM (2006) Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transpl 6:783–790

Rull R, Vidal O, Momblan D, González FX, López-Boado MA, Fuster J, Grande L, Bruguera M, Cabrer K, García-Valdecasas JC (2003) Evaluation of potential liver donors: limits imposed by donor variables in liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 9:389–393

Botha P (2009) Extended donor criteria in lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 14:206–210

Yeung JC, Cypel M, Waddell TK, van Raemdonck D, Keshavjee S (2009) Update on donor assessment, resuscitation, and acceptance criteria, including novel techniques–non-heart-beating donor lung retrieval and ex vivo donor lung perfusion. Thorac Surg Clin 19:261–274

Oto T (2008) Lung transplantation from donation after cardiac death (non-heart-beating) donors. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 56:533–538

Snell GI, Levvey BJ, Oto T, McEgan R, Pilcher D, Davies A, Marasco S, Rosenfeldt F (2008) Early lung transplantation success utilizing controlled donation after cardiac death donors. Am J Transplant 8:1282–1289

Yee AH, Rabinstein AA, Thapa P, Mandrekar J, Wijdicks EF (2010) Factors influencing time to death after withdrawal of life support in neurocritical patients. Neurology 74:1380–1385

Rabinstein AA, Yee AH, Mandrekar J, Fugate JE, de Groot YJ, Kompanje EJ, Shutter LA, Freeman WD, Rubin MA, Wijdicks EF (2012) Prediction of potential for organ donation after cardiac death in patients in neurocritical state: a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 11:414–419

de Groot YJ, Lingsma HF, Bakker J, Gommers DA, Steyerberg E, Kompanje EJ (2012) External validation of a prognostic model predicting time of death after withdrawal of life support in neurocritical patients. Crit Care Med 40:233–238

Rosner B (1995) Fundamentals of biostatistics. Wadsworth, Belmont

Shemie SD, Doig C, Dickens B, Byrne P, Wheelock B, Rocker G, Baker A, Seland TP, Guest C, Cass D, Jefferson R, Young K, Teitelbaum J, Pediatric Reference Group, Neonatal Reference Group (2006) Severe brain injury to neurological determination of death: canadian forum recommendations. CMAJ 174:S1–S13

Morgan SE, Stephenson MT, Harrison TR, Afifi WA, Long SD (2008) Facts versus ‘feelings’. How rational is the decision to become an organ donor? J Health Psychol 13:644–658

Antonelli M, Bonten M, Chastre J, Citerio G, Conti G, Curtis JR, De Backer D, Hedenstierna G, Joannidis M, Macrae D, Mancebo J, Maggiore SM, Mebazaa A, Preiser JC, Rocco P, Timsit JF, Wernerman J, Zhang H (2012) Year in review in intensive care medicine 2011: i. Nephrology, epidemiology, nutrition and therapeutics, neurology, ethical and legal issues, experimentals. Intensive Care Med 38:192–209

Kohn R, Rubenfeld G, Levy M, Ubel P, Halpern S (2011) Rule of rescue or the good of the many? An analysis of physicians’ and nurses’ preferences for allocating ICU beds. Intensive Care Med 37:1210–1217

Weng L, Joynt G, Lee A, Du B, Leung P, Peng J, Gomersall C, Hu X, Yap H (2011) Attitudes towards ethical problems in critical care medicine: the Chinese perspective. Intensive Care Med 37:655–664

Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, Sjokvist P, Dodek P, Griffith L, Freitag A, Varon J, Bradley C, Levy M, Finfer S, Hamielec C, McMullin J, Weaver B, Walter S, Guyatt G, Group LoCSIatCCCT (2003) Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med 349:1123–1132

Turgeon AF, Lauzier F, Simard JF, Scales DC, Burns KE, Moore L, Zygun DA, Bernard F, Meade MO, Dung TC, Ratnapalan M, Todd S, Harlock J, Fergusson DA (2011) Mortality associated with withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a Canadian multicentre cohort study. CMAJ 183:1581–1588

Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, Winn HR, Longstreth WT Jr (2001) Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology 56:766–772

Hemphill JC 3rd, Newman J, Zhao S, Johnston SC (2004) Hospital usage of early do-not-resuscitate orders and outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 35:1130–1134

Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Gonzales NR, Longwell PJ, Smith MA, Garcia NM, Morgenstern LB (2007) Early care limitations independently predict mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 68:1651–1657

Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C, Collett D, Rudge C (2006) Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: audit of intensive care records. BMJ 332:1124–1127

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Mr. Scott Gordon, Mrs. Kathleen LeBranch, and Mrs. Patrica Thompson who contributed to the individual and population data abstraction. In part from the Human Procurement and Exchange Program (HOPE) of Northern Alberta and the Royal Alexandra Hospital Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Kutsogiannis is employed as the medical director of the Human Organ Procurement and Exchange program for Northern Alberta.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper followed the STROBE guideline for reporting retrospective studies (BMJ 2007).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kutsogiannis, D.J., Asthana, S., Townsend, D.R. et al. The incidence of potential missed organ donors in intensive care units and emergency rooms: a retrospective cohort. Intensive Care Med 39, 1452–1459 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-2952-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-2952-6