Abstract

Purpose

We examine evidence for whether decreases in externalizing behaviors are driven by the absence of risk (e.g., lack of poor housing quality) or the presence of something positive (e.g., good housing quality). We also review evidence for whether variables have promotive (main) effects or protective (buffering) effects within contexts of risks.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of longitudinal studies. First, we review studies (n = 7) that trichotomized continuous predictor variables. Trichotomization tests whether the positive end of a variable (e.g., good housing quality) is associated with lower delinquency compared with the mid-range, and whether mid-range scores are associated with fewer problems than the “risky” end (e.g., poor housing quality). We do not review dichotomous variables, because the interpretation of results is the same regardless of which value is the reference group. To address our second aim, we review studies (n = 53) that tested an interaction between a risk and positive factor.

Results

Both the absence of risk and the presence of positive characteristics were associated with low externalizing problems for IQ, temperament, and some family variables. For other variables, associations with low delinquency involved only the presence of something positive (e.g., good housing quality), or the absence of a risk factor (e.g., community crime). The majority of studies that tested interactions among individual and family characteristics supported protective, rather than promotive, effects. Few studies tested interactions among peer, school, and neighborhood characteristics.

Conclusions

We discuss implications for conceptual understanding of promotive and protective factors and for intervention and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Problem behaviors, such as oppositionality, hyperactivity/impulsivity, rule-breaking, aggression, and violence, are among the most burdensome and prevalent forms of psychopathology faced by children and adolescents [1–3]. These outwardly directed behaviors load onto an “externalizing” factor of psychopathology [4], which includes clinical disorders, such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and substance use dependence [4–6]. Externalizing problems are a major public health concern that place youth at risk for poor outcomes into adulthood, including academic underachievement, interpersonal problems, employment difficulties, incarceration, long-term substance dependence, and persistent antisocial behavior [7–9].

An underexplored question in the field is whether low rates of externalizing problems are driven by the absence of something negative (e.g., lack of neighborhood deprivation), the presence of something positive (e.g., neighborhood affluence), or both [10–12]. This has important implications for the field’s conceptual understanding of factors associated with reductions in antisocial behavior, and for informing intervention. If, for example, the absence of neighborhood poverty predicted low externalizing problems, but the presence of neighborhood affluence did not, it would be clear that interventions should focus on shifting neighborhoods from low to middle income, but not necessarily on making neighborhoods wealthy.

A trichotomization approach is one way to test this question. Trichotomization compares the middle half of a variable’s distribution to the upper and lower quartiles to test for linear or non-linear effects [11, 12]. A linear effect is indicated when children falling in the mid-range have a fewer externalizing problems than those in the lower quartile, and those in the upper quartile have a fewer externalizing problems than those in the mid-range. Alternatively, there may be non-linear effects if, for example, only the upper quartile, but not the lower quartile, differs significantly from the mid-range on externalizing problems. Thus, it may be that the absence of risk (i.e., the mid-range compared with the risky quartile), the presence of something positive (i.e., the positive quartile compared with the mid-range), or both are associated with decreases in externalizing problems.

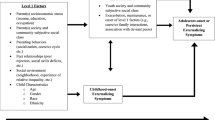

A separate question is whether variables have promotive or protective effects on externalizing psychopathology [13–15]. Promotive factors (i.e., direct protective factors [16]) are main effects associated with decreases in problematic outcomes. Protective factors (i.e., buffering factors [16]) buffer youth from externalizing problems in the face of risk. To distinguish whether a variable has a promotive or protective effect, studies must test an interaction term between a positive factor and a risk factor. A promotive effect would be indicated if there was a significant main effect, but not a significant interaction, such that rates of externalizing problems decrease as the positive factor increases (see Fig. 1 for an example plot). If the interaction is significant and suggests a protective effect, then the high risk group will experience reductions in externalizing problems when exposed to high, compared with low, levels of the positive factor, but externalizing problems will be low and unassociated with the positive factor in the low-risk group (see Fig. 2 for an example plot). Although there have been many reviews of risk factors for externalizing psychopathology among children and adolescents (e.g., [17–22]), only a few have included [23, 24] or focused specifically [16, 25–27] on promotive and protective factors. In addition, extant reviews have focused on identifying variables associated with decreases in externalizing problems, but there has been a lack of synthesis regarding which variables tend to have promotive versus protective effects.

The current systematic review has two aims. The first is to review findings from longitudinal studies that employed trichotomization to test for whether the absence of risk and/or the presence of something positive relates to decreased likelihood of externalizing behaviors. The second aim is to review findings from studies that tested interactions between a positive factor and a risk factor to identify whether the positive variable has a promotive effect, or a protective effect that mitigates the association between a risk factor and externalizing problems.

Method

Searches were conducted in PubMed and PsycInfo to identify articles written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2005 and December 2015. Search terms were: Risk and (Protective or Promotive) and (Externaliz* or Antisocial or Violen* or Aggress* or Problem Behavior or Delinquen* or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or Conduct Disorder or Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Substance Use Dependen*) and (Child or Adolescen*). The initial search resulted in 899 articles from PubMed and 923 articles from PsycInfo. Once duplicates were removed, 1467 articles were screened.

We screened articles in a three-stage process. First, we screened titles and abstracts to exclude studies of outcomes other than externalizing problems as defined by the search terms (e.g., gambling, problematic video game use, sexual risk taking, teen parenthood, internalizing problems; n = 517); child welfare services delivery and utilization (n = 45); and populations with limited generalizability (e.g., autism spectrum disorders, child soldiers; n = 77). Qualitative, measurement development, and intervention development studies (n = 106) and other miscellaneous studies (n = 13) were also excluded.

Second, we read papers and excluded studies that were not empirical (e.g., introductions to special issues; n = 89), sampled adults (n = 103), did not include protective/promotive factors as predictors (n = 74), and did not include temporal ordering in the measurement of protective/promotive factors and externalizing outcomes (n = 222). This process yielded 203 empirical articles. Reference lists were reviewed for additional papers that met inclusion/exclusion criteria (n = 31). Third, we screened the final pool of 234 studies and identified those that used trichotomization (n = 7) to review for the first aim, and those that tested interaction effects (n = 53) to address the second aim.

Results

The absence of risk versus the presence of positive factors

In the following section, we review evidence from studies that trichotomized predictor variables to examine whether it is the absence of risk (e.g., not having low IQ) or the presence of something positive (e.g., having above-average IQ) that is associated with decreased rates of externalizing problems. We review variables that are continuously distributed (e.g., low to high IQ) and, therefore, could be trichotomized to test for linear or non-linear effects. We do not review dichotomous variables, because the interpretation of the results is the same regardless of which value is the reference group. It is equally true, for example, that being a girl and not being a boy are associated with a fewer externalizing problems. We present evidence for linear versus non-linear effects of individual-, family, peer-, school-, and neighborhood-level variables. See Table 1 for a summary of findings.

Individual-level variables

Some individual-level variables have demonstrated linear effects, such that youth with scores in the positive end of the distribution have lower delinquency compared with youth with scores in the mid-range. Likewise, youth with scores in the mid-range have lower delinquency compared with those with scores in the risky end. One study reported this pattern for IQ, such that children with above-average IQ had significantly lower risk of externalizing problems than children with IQ in the average range, and children in the average range had significantly lower risk of externalizing problems than children whose IQ fell in the below-average range [10]. Similarly, low, compared with average, attention problems/ADHD is associated with lower rates of violence [28, 29], and average, compared with high, attention problems/ADHD is associated with less violence [28]. Of note, only one of the studies [28] on attention problems/ADHD reported both comparisons, and the other [29] did not report differences between mid-range and high attention problems/ADHD.

Regarding children’s temperament, van der Laan and colleagues [30] found support for linear effects of surgency (e.g., activity level, behavioral inhibition, and impulsivity) and effortful control (e.g., ability to shift attention when needed and suppress inappropriate responses). Low surgency and high effortful control were associated with lower delinquency compared with average scores on these measures, and average scores were associated with lower delinquency compared with high surgency and low effortful control. Taken together, these linear effects suggest that the absence of risk (i.e., not having low IQ, high ADHD symptoms/attention problems, high surgency, or low effortful control) and the presence of the positive side of the variables (i.e., having high IQ, low ADHD symptoms/attention problems, low surgency, and high effortful control) are associated with a fewer externalizing problems.

Several variables demonstrated non-linear effects in the direction that suggests that the absence of risk, rather than the presence of something positive, drives reductions in externalizing problems. In other words, youth with scores in the mid-range have lower delinquency compared with those with scores in the risky end, but youth with scores in the positive end do not have lower delinquency compared with those with scores in the mid-range. This pattern was supported for delayed visual memory, such that the mid-range, compared with low, scores were associated with lower delinquency, but mid-range and high scores did not differ significantly on delinquency [10]. Similarly, compared with youth with above-average interpersonal callousness, youth with mid-range scores have lower rates of violence, but youth with below-average interpersonal callousness are not less violent than those in the mid-range [31]. In sum, not having poor delayed verbal memory and high interpersonal callousness decreased rates of externalizing problems.

On the other hand, some variables demonstrated non-linear effects suggesting that the presence of the positive end of the variable is associated with lower delinquency compared with the average range, but youth with average scores do not have lower delinquency compared with those with scores reflecting risk. High, compared with average, scores on sustained attention and delayed verbal memory are associated with lower delinquency, but mid-range and low scores on these measures do not differ significantly [10]. Similarly, youth with high, compared with mid-range, aspirations for higher education are less likely to perpetrate violence, but those with mid-range aspirations are not less violent than those with low aspirations [32]. The same pattern has been reported for shyness, with high shyness representing the positive end of the variable, and low shyness representing the risky end [30]. In addition, youth with low depressive symptoms are less likely to perpetrate violence than those in the mid-range, but those in the mid-range are not less violent than those with high depressive symptoms [31, 33]. Youth with higher ability to refuse engaging in antisocial behavior [28] and who espouse more negative attitudes toward delinquency [29, 31] engage in less delinquency compared with youth with mid-range scores, but youth with mid-range scores do not differ on rates of delinquency compared with youth with poor refusal skills or pro-delinquency beliefs. Findings suggest that it is the presence of the positive ends of these variables rather than the absence of risk that drives reductions in antisocial behavior.

It is unclear whether academic achievement has a linear or non-linear effect on antisocial behavior. Some studies reported non-linear effects, such that youth with above-average academic achievement had significantly lower risk for violence than those with average achievement, but those with average achievement did not differ from those with below-average achievement [28, 31]. Other studies identified a linear pattern, such that above-average versus average, and average versus below-average, academic achievement was associated with lower violence [30, 32, 33].

Family factors

The majority of family level variables tested in prior studies demonstrated linear effects. Good family management strategies (e.g., clear contingencies) [28] and healthy family functioning [30] are associated with less violence compared with the mid-range of these variables, and the mid-range is associated with less violence compared with poor strategies (e.g., unclear rules) and family dysfunction. Similarly, lower, compared with average, and average compared with high, parental stress is associated with decreased risk for delinquency [30]. These findings suggest that children living in families that have good management strategies, healthy functioning, and low parental stress, and do not have poor management strategies, dysfunction, and high parental stress, are at decreased risk for externalizing problems. In contrast, one study reported a non-linear effect; low, compared with mid-range, levels of parental overprotection were associated with less delinquency, but mid-range and high levels of overprotection did not differ significantly on delinquency [30].

Peer factors

One study found that youth whose ability to get along with peers fell in the mid-range engaged in less violence than youth who had below-average abilities to get along with peers [31]. However, youth whose ability to get along with peers was above-average did not engage in less violence than those with average abilities [31]. These findings suggest that the ability to get along with peers has a non-linear effect, such that the presence (versus the absence) of this ability lowers externalizing outcomes.

In the case of affiliating with delinquent peers, studies have reported linear and non-linear effects. Two studies found a linear effect, such that children with a few, compared with mid-range, and mid-range compared with many, delinquent peer affiliations had lower rates of antisocial behavior [31, 33]. A third study reported non-linear effects, such that youth with mid-range delinquent affiliations had lower rates of violence in adolescence compared with those with many delinquent affiliations, but youth with a few delinquent affiliations did not differ significantly from those in the mid-range [32]. However, the opposite non-linear effect emerged when predicting violence in young adulthood: youth with a few delinquent peer affiliations had lower rates of violence compared with the mid-range, but youth with mid-range and many delinquent affiliations did not differ significantly on violence. Compared with youth with peers falling in the mid-range of prosocial behavior, youth who affiliated with peers with above-average prosocial behavior was less likely to perpetrate violence [28]. The study did not report comparisons between youth with peers in the mid-range and with above-average prosocial behavior, making it unclear whether this represents a linear or non-linear effect.

School factors

Only non-linear effects have been reported for school variables. Youth with more positive attitudes toward school do not differ on violence from those in the mid-range, but those with mid-range school attitudes engage in less violence than those with negative attitudes [31, 33]. On the other hand, high, compared with average, school attachment is associated with lower delinquency, but children with low and mid-range school attachment do not differ on delinquency [28]. Thus, having positive school attachment, and not having negative attitudes/dissatisfaction, is associated with lower levels of externalizing problems.

Neighborhood factors

Perceived availability and exposure to marijuana in the neighborhood has a linear effect on violence, such that low compared with mid-range, and mid-range compared with high, levels of perceived availability and exposure to marijuana are associated with less violence [28]. Loeber and colleagues [10] found a non-linear effect of housing quality, such that the presence of good housing quality compared with the mid-range, but not mid-range compared with poor housing quality, was associated with low delinquency. There is mixed evidence on the type of non-linear effect that community crime exerts on violence. One study found that youth living in neighborhoods with average levels of crime/poverty had lower rates of violence than those living in neighborhoods with high crime/poverty, but youth exposed to low versus average crime/poverty did not differ significantly on violence [31]. Another study found the opposite non-linear pattern: youth living in low crime neighborhoods were less likely to engage in delinquent behavior compared with those in neighborhoods with average levels of crime, but delinquent behavior did not differ between youth living in average versus high crime neighborhoods [10]. Thus, it is not clear whether reductions in delinquency are more strongly associated with the absence of high crime rates or the presence of very low crime rates.

Promotive versus protective effects

The following section reviews studies that tested an interaction term to determine if a variable involves a promotive main effect or a protective buffering effect. We examined studies that tested for (1) individual characteristics that moderate effects of risky environments, (2) environmental characteristics that moderate effects of individual-level risk, and (3) environmental characteristics that moderate effects of risky environments. Table 1 shows findings by variable, and we provide a summary below. This review focuses on behavioral and cognitive individual difference variables as opposed to genetic or physiological ones. A recent review discussed biological protective factors [27]. We also did not review moderators of intervention effects, because we focused on the question of promotive versus protective effects within risky contexts.

Individual-level promotive factors and moderators of risky environments

Several studies tested whether individual strengths buffer risk associated with family environment, such as harsh discipline and hostility. Positive individual-level characteristics of higher cognitive ability [34], lower levels of difficult temperament [35], attending or having completed high school (or GED) [36], and low endorsement of aggressive norms [37] had protective effects within risky family contexts. One study found that easy infant temperament exerted a promotive effect on preschoolers’ problem behaviors, but did not significantly buffer against family level risk [38].

Studies have also identified individual-level moderators of risk associated with extra-familial contexts. The strength of the association between affiliating with delinquent peers and engaging in delinquent behavior is attenuated by spending more time in prosocial activities (e.g., sports team and musical activity) [39], low endorsement of aggressive norms [37], and high self-esteem [36]. One study found that higher, compared with lower, levels of self-confidence decreased externalizing problems among youth living in poverty [40]. Finally, one study identified a promotive effect of self-perceived scholastic competence, which did not buffer risk associated with peer rejection [41].

Some interaction effects indicated that decreases in externalizing problems occurred in low, but not high, risk environments. One study found that girls with social anxiety were at decreased risk for substance use if they reported that their peers had low, compared with high, rates of substance use [42]. This pattern does not support a buffering hypothesis, but rather suggests that an individual characteristic (social anxiety) may allow girls to benefit more from a low risk environment [43]. In addition, the degree to which individual-level characteristics can protect youth from environmental risks may depend on the number of stressors present in the environment. One study found that children’s individual strengths buffered risk for externalizing problems at low, but not high, numbers of family and neighborhood stressors [44].

Overall, the interaction effects identified in this section support a buffering hypothesis, such that positive individual characteristics tend to attenuate the relation between risky environments and externalizing problems. The only exceptions were for easy infant temperament and high scholastic competence, which had promotive effects associated with decreases in externalizing problems regardless of risk.

Environmental promotive factors and moderators of individual-level risk

Positive aspects of the family environment can have buffering effects for children with individual-level risk factors for externalizing problems. Among children born in Mexico, the relation between high prenatal lead exposure and ADHD is attenuated by higher maternal self-esteem [45]. Higher levels of positive parenting (e.g., monitoring, involvement, and warmth) buffer children against risk associated with prenatal cocaine exposure [46], difficult temperament [47–49], and history of externalizing problems [50–52]. Among children who have been physically abused, positive parenting is protective for children with low self-regulation [53]. In contrast, some studies found support for promotive effects of family factors rather than moderation of individual-level risk. One study found that parental disapproval of antisocial behavior had promotive effects, but did not moderate risk associated with a history of abuse [54]. Marsiglia et al. [55] found that among children from Mexican immigrant families, high family cohesion and familism had promotive effects on externalizing outcomes, but did not buffer against risk posed by low acculturation. Thus, although many positive aspects of the family environment buffer individual-level risks, some have promotive effects instead.

Positive aspects of the peer, school, and neighborhood environments can also promote positive outcomes or protect children with individual-level risk factors. For example, for girls, being liked by peers attenuates the relation between difficult temperament and hyperactivity [56]. Another study found that high commitment to school was associated with a fewer externalizing problems, but did not buffer risk associated with prior maltreatment [54]. Neighborhoods with higher social cohesion provide protective effects for youth with histories of externalizing problems [57]. In sum, some extra-familial environmental characteristics have promotive effects, and others have protective effects for youth with risky individual characteristics.

Environmental promotive factors and moderators of environmental risk

Children’s environments comprise a mix of risk and positive factors that can interact to reduce externalizing problems. High maternal empathy [58] and sensitivity [59] have protective effects in the face of household stress and conflict. High parent–child relationship quality buffers children from risk associated with a parent’s history of delinquency [60]. Grandmother involvement is protective for children exposed to harsh maternal discipline [61]. The relation between harsh discipline and externalizing problems is also attenuated by positive parenting [62–64]. There is some evidence that this effect may be culture-specific. Lansford and colleagues collected data in China, Colombia, Jordan, Kenya, Philippines, Thailand, Italy, and the US, and found that maternal warmth buffered the effects of corporal punishment on aggression only among African American families in the US, and had promotive effects in Jordan and Kenya [64]. However, an additional study that used data from a large, US birth-cohort study that oversampled African American and Hispanic families found that maternal warmth did not have a promotive or protective effect on later aggression in the face of spanking [65]. This study did not test whether these effects differed by race or ethnicity, so it is unclear whether buffering effects held within the African American subgroup. Although there is some evidence for promotive effects, the majority these findings support the hypothesis that positive family factors can buffer risk associated with negative aspects of the family environment.

Several studies tested whether positive aspects of the family environment buffer youth against risks outside of the home. Positive parenting attenuates the relation between externalizing problems and attending a school with higher norms for aggression [66], living in a more disadvantaged neighborhood [67, 68], and exposure to community violence [69–72] or cumulative risk [73]. Perceived parental support [74], positive parent-adolescent interaction style [75], and maternal socialization of coping [76] buffer risk associated with life stress. Thus, it appears that positive family characteristics provide protective effects for youth exposed to stressful environments and negative life events. On the other hand, a handful of studies found support for promotive, rather than protective, effects of positive family factors in the face of peer substance use [77], neighborhood disadvantage [78], and community violence [79, 80].

Positive aspects of extra-familial environments can also promote positive outcomes or protect youth against risk factors within or outside of their families. Positive peer relationships buffer against externalizing problems for youth exposed to community violence [72]. Higher levels of school connectedness promote decreases in violence, but do not buffer against exposure to community violence [70]. Positive neighborhood factors, such as social cohesion and collective efficacy, buffer children against risk associated with neglect [81], caregiver depression (among neglected children) [82], and neighborhood deprivation [83].

Stoddard and colleagues [84] included individual, family, and peer factors in measures of cumulative positive and risk factors. They found that more cumulative positive factors buffered against violence for youth exposed to high, compared with low, cumulative risk. The cumulative positive score was not associated with violence among youth exposed to lower cumulative risks. Thus, it appears that overall, positive factors are protective in contexts of high, compared with low, risk.

In sum, our review suggests that positive aspects of the family environment can buffer risk associated with domestic violence, parental history of antisocial behavior, parental and life stress, and high norms for aggression at school. Findings were mixed regarding whether positive parenting practices have protective, promotive, or no effect against harsh discipline, community violence, and neighborhood disadvantage. A few studies examined whether positive peer, school, and neighborhood factors moderated associations between risk and externalizing outcomes. Those that did found support for buffering effects, expect for school connectedness, which had promotive effects.

Discussion

The current review provides a novel synthesis of the literature on factors that decrease likelihood of externalizing problems in childhood and adolescence. We examined whether it is the absence of risk or the presence of something positive that drives reductions in externalizing behaviors. We also reviewed findings on whether certain variables tend to have promotive main effects or protective buffering effects in various risky contexts.

We reviewed studies that used a trichotomization approach to determine if reductions in externalizing problems involve either the absence of risk or the presence of something positive (i.e., non-linear effects), or both (i.e., linear effects). IQ, temperament, family management, family functioning, and parental stress had linear effects, such that lower delinquency was associated with the mid-range compared with the risky end of the variable, and the positive end compared with the mid-range. Fewer externalizing problems were associated with not having high attention problems/ADHD, poor delayed visual memory, high depression, high interpersonal callousness, poor skills to refuse engagement in antisocial behavior, high parental overprotection, affiliating with many antisocial peers, low ability to get along with peers, negative attitude/dissatisfaction with school, high perceived availability, and exposure to marijuana in the neighborhood. In contrast, the presence of the following (rather than the absence of the risky end of these variables) was associated with fewer externalizing problems: high academic aspirations, high sustained attention, high delayed verbal memory, high shyness, negative attitudes toward delinquency, affiliating with prosocial peers, high attachment to school, and good housing quality. There were mixed findings regarding whether academic achievement had linear or non-linear effects on antisocial behavior, and whether the absence of high crime or the presence of very low crime decreased externalizing problems. Future work should examine whether effects depend on contextual variables.

These findings provide guidance for whether interventions should aim to reduce risk, foster positive factors, or both to improve children’s outcomes. For variables demonstrating non-linear effects, resources should be allocated to move children out of the risky quartile and into the mid-range, or from the mid-range into the positive quartile, to reduce risk for externalizing problems. For instance, only youth with high, compared with average school attachment, but not average compared with low school attachment, were at decreased risk for externalizing problems. This suggests that interventions should not stop once children are no longer disengaged or antagonistic toward school, but rather aim to foster positive school attachment. For variables with linear effects, interventions that result in even incremental movements in the dependent variable will reduce risk for externalizing problems.

Our review of promotive versus protective effects revealed some consistent findings. Positive individual characteristics tended to have protective effects, which suggest that they are particularly important for youth in risky environments. In addition, positive parenting practices buffered youth from individual-level (e.g., difficult temperament), family level (e.g., harsh discipline), and neighborhood-level (e.g., neighborhood disadvantage) risks. There were mixed findings regarding whether positive parenting practices buffered risk associated with community violence. A few studies examined interactions between peer, school, and neighborhood characteristics on children’s externalizing behaviors, and findings were mixed regarding whether these characteristics tended to have promotive versus protective effects. Variables demonstrating protective effects should be considered particularly important targets for intervention for children exposed to risk, and variables with promotive effects should be targeted within universal prevention strategies.

The current review has several limitations. First, a relatively few studies used a trichotomization approach. Second, although trichotomization is a particularly appropriate technique to address our research question, it has drawbacks, such as utilizing relatively arbitrary cut-points. Third, the majority of trichotomization and interaction studies reviewed were conducted in the US or high-income European countries. Thus, findings may not generalize to low- and middle-income countries, and certain effects may be culture- or context-specific. For example, in Lansford and colleagues’ [64] study of families from developed and developing countries, maternal warmth mitigated adverse effects of harsh discipline only among African Americans in the US. Additional research should be conducted to gain an international perspective on promotive and protective factors for children. Finally, our review of promotive versus protective effects may be somewhat skewed toward identifying buffering effects, because studies may not publish nonsignificant interaction findings, even if results demonstrate a promotive effect.

In summary, determining whether reductions in externalizing and other common childhood problem behaviors are associated with the presence of positive factors and/or the absence of risk factors has implications for prevention and intervention goals. Knowledge of whether these positive factors have promotive or protective effects provides additional information about intervention targets. Future research should test whether findings generalize cross culturally and probe the sensitivity of the trichotomization approach using different cut-points (e.g., deciles [85]) or alternative statistical methods to determine whether a variable has a linear versus non-linear effect.

References

Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R, Vostanis P (2011) The burden of caring for children with emotional or conduct disorders. Int J Fam Med 2011:e801203. doi:10.1155/2011/801203

Merikangas KR, He J-P, Brody D et al (2010) Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics 125:75–81. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2598

Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M et al (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Study-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49:980–989. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID et al (2004) The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: generating new hypotheses. J Abnorm Psychol 113:358–385. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358

Lahey BB, Van Hulle C, Singh A et al (2011) Higher-order genetic and environmental structure of prevalent forms of child and adolescent psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:181–189. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.192

Beesdo-Baum K, Höfler M, Gloster AT et al (2009) The structure of common mental disorders: a replication study in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 18:204–220. doi:10.1002/mpr.293

Krueger RF, Markon KE (2006) Reinterpreting comorbidity: a model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2:111–133. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213

Reef J, Diamantopoulou S, Van Meurs I et al (2010) Developmental trajectories of child to adolescent externalizing behavior and adult DSM-IV disorder: results of a 24-year longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:1233–1241. doi:10.1007/s00127-010-0297-9

Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM et al (2008) Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 20:673. doi:10.1017/S0954579408000333

Loeber R, Pardini DA, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Raine A (2007) Do cognitive, physiological, and psychosocial risk and promotive factors predict desistance from delinquency in males? Dev Psychopathol 19:867–887. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000429

Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Wei E et al (2002) Risk and promotive effects in the explanation of persistent serious delinquency in boys. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:111. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.111

Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Farrington DP et al (1993) The double edge of protective and risk factors for delinquency: interrelations and developmental patterns. Dev Psychopathol 5:683–701. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006234

Rutter M (1985) Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 147:598–611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598

Masten AS, Garmezy N (1985) Risk, vulnerability, and protective factors in developmental psychopathology. In: Lahey BB, Kazdin AE (eds) Advances in clinical child psychology. Springer, New York, pp 1–52

Luthar SS (1993) Annotation: methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 34:441–453. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01030.x

Lösel F, Farrington DP (2012) Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. Am J Prev Med 43:S8–S23. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.029

Murray J, Farrington D (2010) Risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency: key findings from longitudinal studies. Can J Psychiatry 55:633–642

Jaffee SR, Strait LB, Odgers CL (2012) From correlates to causes: can quasi-experimental studies and statistical innovations bring us closer to identifying the causes of antisocial behavior? Psychol Bull 138:272–295. doi:10.1037/a0026020

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD (2003) Taking stock of delinquency: an overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies. Springer, New York

Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (2003) Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. Guilford Press, New York

Gershoff ET (2002) Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull 128:539. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.128.4.539

Wilson HW, Stover CS, Berkowitz SJ (2009) Research review: the relationship between childhood violence exposure and juvenile antisocial behavior: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:769–779. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01974.x

Crews SD, Bender H, Cook CR et al (2007) Risk and protective factors of emotional and/or behavioral disorders in children and adolescents: a mega-analytic synthesis. Behav Disord 32:64–77

Vagi KJ, Rothman EF, Latzman NE et al (2013) Beyond correlates: a review of risk and protective factors for adolescent dating violence perpetration. J Youth Adolesc 42:633–649. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9907-7

Loeber R, Slot NW, Stouthamer-Loeber M (2006) A three-dimensional, cumulative developmental model of serious delinquency. In: Wikström P-OH, Sampson RJ (eds) The explanation of crime. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 153–194

Lösel F, Bender D (2003) Protective factors and resilience. In: Farrington DP, Coid JW (eds) Early prevention of adult antisocial behavior. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 130–204. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511489259.006

Portnoy J, Chen FR, Raine A (2013) Biological protective factors for antisocial and criminal behavior. J Crim Justice 41:292–299. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.06.018

Herrenkohl TI, Lee J, Hawkins JD (2012) Risk versus direct protective factors and youth violence: Seattle Social Development Project. Am J Prev Med 43:S41–S56. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.030

Van Domburgh L, Loeber R, Bezemer D et al (2009) Childhood predictors of desistance and level of persistence in offending in early onset offenders. J Abnorm Child Psychol 37:967–980

van der Laan AM, Veenstra R, Bogaerts S et al (2010) Serious, minor, and non-delinquents in early adolescence: the impact of cumulative risk and promotive factors. The TRAILS study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:339–351. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9368-3

Pardini DA, Loeber R, Farrington DP, Stouthamer-Loeber M (2012) Identifying direct protective factors for nonviolence. Am J Prev Med 43:S28–S40. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.024

Bernat DH, Oakes JM, Pettingell SL, Resnick M (2012) Risk and direct protective factors for youth violence: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Prev Med 43:S57–S66. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.023

Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Schoeny ME (2012) Risk and direct protective factors for youth violence: results from the centers for disease control and prevention’s multisite violence prevention project. Am J Prev Med 43:S67–S75. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.025

Flouri E, Tzavidis N, Kallis C (2010) Adverse life events, area socioeconomic disadvantage, and psychopathology and resilience in young children: the importance of risk factors’ accumulation and protective factors’ specificity. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19:535–546. doi:10.1007/s00787-009-0068-x

Miner JL, Clarke-Stewart KA (2008) Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Dev Psychol 44:771–786. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.771

Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Bushway SD et al (2014) Shelter during the storm: a search for factors that protect at-risk adolescents from violence. Crime Delinq 60:379–401. doi:10.1177/0011128710389585

Farrell AD, Henry DB, Schoeny ME et al (2010) Normative beliefs and self-efficacy for nonviolence as moderators of peer, school, and parental risk factors for aggression in early adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39:800–813. doi:10.1080/15374416.2010.517167

Derauf C, LaGasse L, Smith L et al (2011) Infant temperament and high risk environment relate to behavior problems and language in toddlers. J Dev Behav Pediatr JDBP 32:125–135. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e31820839d7

Kaufmann DR, Wyman PA, Forbes-Jones EL, Barry J (2007) Prosocial involvement and antisocial peer affiliations as predictors of behavior problems in urban adolescents: main effects and moderating effects. J Community Psychol 35:417–434. doi:10.1002/jcop.20156

Li ST, Nussbaum KM, Richards MH (2007) Risk and protective factors for urban African-American youth. Am J Community Psychol 39:21–35. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9088-1

Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP (2006) Resilient adolescent adjustment among girls: buffers of childhood peer rejection and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 34:825–839. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9062-7

Zehe JM, Colder CR, Read JP et al (2013) Social and generalized anxiety symptoms and alcohol and cigarette use in early adolescence: the moderating role of perceived peer norms. Addict Behav 38:1931–1939. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.013

Pluess M, Belsky J (2013) Vantage sensitivity: individual differences in response to positive experiences. Psychol Bull 139:901–916. doi:10.1037/a0030196

Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE et al (2007) Individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children: a cumulative stressors model. Child Abuse Negl 31:231–253. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.011

Xu J, Hu H, Wright R et al (2015) Prenatal lead exposure modifies the impact of maternal self-esteem on children’s inattention behavior. J Pediatr 167:435–441. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.04.057

Warner TD, Behnke M, Eyler FD, Szabo NJ (2011) Early adolescent cocaine use as determined by hair analysis in a prenatal cocaine exposure cohort. Neurotoxicol Teratol 33:88–99. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2010.07.003

Kochanska G, Kim S (2013) Difficult temperament moderates links between maternal responsiveness and children’s compliance and behavior problems in low-income families. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 54:323–332. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12002

Clark DA, Donnellan MB, Robins RW, Conger RD (2015) Early adolescent temperament, parental monitoring, and substance use in Mexican-origin adolescents. J Adolesc 41:121–130. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.02.010

Sentse M, Veenstra R, Lindenberg S et al (2009) Buffers and risks in temperament and family for early adolescent psychopathology: generic, conditional, or domain-specific effects? The trails study. Dev Psychol 45:419–430. doi:10.1037/a0014072

Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE Jr et al (2007) Maternal depression and early positive parenting predict future conduct problems in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Dev Psychol 43:70–82. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70

Lösel F, Bender D (2014) Aggressive, delinquent, and violent outcomes of school bullying: do family and individual factors have a protective function? J Sch Violence 13:59–79. doi:10.1080/15388220.2013.840644

Bushway SD, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ et al. (2013) Are risky youth less protectable as they age? The dynamics of protection during adolescence and young adulthood. Justice Q 30:84–116. doi:10.1080/07418825.2011.592507

Kim J, Haskett ME, Longo GS, Nice R (2012) Longitudinal study of self-regulation, positive parenting, and adjustment problems among physically abused children. Child Abuse Negl 36:95–107. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.016

Herrenkohl TI, Tajima EA, Whitney SD, Huang B (2005) Protection against antisocial behavior in children exposed to physically abusive discipline. J Adolesc Health 36:457–465. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.025

Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S (2009) Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest United States. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work 18:203–220. doi:10.1080/15313200903070965

Berdan LE, Keane SP, Calkins SD (2008) Temperament and externalizing behavior: social preference and perceived acceptance as protective factors. Dev Psychol 44:957–968. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.957

Kurlychek MC, Krohn MD, Dong B et al (2012) Protection from risk: exploration of when and how neighborhood-level factors can reduce violent youth outcomes. Youth Violence Juv Justice 10:83–106. doi:10.1177/1541204011422088

Walker LO, Cheng C-Y (2007) Maternal empathy, self-confidence, and stress as antecedents of preschool children’s behavior problems. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 12:93–104. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6155.2005.00098.x

Manning LG, Davies PT, Cicchetti D (2014) Interparental violence and childhood adjustment: how and why maternal sensitivity is a protective factor. Child Dev 85:2263–2278. doi:10.1111/cdev.12279

Dong B, Krohn MD (2015) Exploring intergenerational discontinuity in problem behavior bad parents with good children. Youth Violence Juv Justice 13:99–122. doi:10.1177/1541204014527119

Barnett MA, Scaramella LV, Neppl TK et al (2010) Grandmother involvement as a protective factor for early childhood social adjustment. J Fam Psychol JFP J Div Fam Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 43(24):635–645. doi:10.1037/a0020829

Germán M, Gonzales NA, Bonds McClain D et al (2013) Maternal warmth moderates the link between harsh discipline and later externalizing behaviors for mexican american adolescents. Parent Sci Pract 13:169–177. doi:10.1080/15295192.2013.756353

Alink LRA, Mesman J, Van Zeijl J et al (2009) Maternal sensitivity moderates the relation between negative discipline and aggression in early childhood. Soc Dev 18:99–120. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00478.x

Lansford JE, Sharma C, Malone PS et al (2014) Corporal punishment, maternal warmth, and child adjustment: a longitudinal study in eight countries. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 43:670–685. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.893518

Lee SJ, Altschul I, Gershoff ET (2013) Does warmth moderate longitudinal associations between maternal spanking and child aggression in early childhood? Dev Psychol 49:2017–2028. doi:10.1037/a0031630

Farrell AD, Henry DB, Mays SA, Schoeny ME (2011) Parents as moderators of the impact of school norms and peer influences on aggression in middle school students. Child Dev 82:146–161. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01546.x

Supplee LH, Unikel EB, Shaw DS (2007) Physical environmental adversity and the protective role of maternal monitoring in relation to early child conduct problems. J Appl Dev Psychol 28:166–183. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.12.001

Roche KM, Ensminger ME, Cherlin AJ (2007) Variations in parenting and adolescent outcomes among African American and Latino families living in low-income, urban areas. J Fam Issues 28:882–909. doi:10.1177/0192513X07299617

Veira Y, Finger B, Eiden RD, Colder CR (2014) Child behavior problems: role of cocaine use, parenting and child exposure to violence. Psychol Violence 4:266–280. doi:10.1037/a0036157

Ozer EJ (2005) The impact of violence on urban adolescents longitudinal effects of perceived school connection and family support. J Adolesc Res 20:167–192. doi:10.1177/0743558404273072

Miller RN, Fagan AA, Wright EM (2014) The moderating effects of peer and parental support on the relationship between vicarious victimization and substance use. J Drug Issues 44:362–380. doi:10.1177/0022042614526995

Jain S, Cohen AK (2013) Behavioral adaptation among youth exposed to community violence: a longitudinal multidisciplinary study of family, peer and neighborhood-level protective factors. Prev Sci 14:606–617. doi:10.1007/s11121-012-0344-8

Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, Zeisel SA, Rowley SJ (2008) Social risk and protective factors for African American children’s academic achievement and adjustment during the transition to middle school. Dev Psychol 44:286–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.286

Carothers SS, Borkowski JG, Lefever JB, Whitman TL (2005) Religiosity and the socioemotional adjustment of adolescent mothers and their children. J Fam Psychol 19:263. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.263

Willemen AM, Schuengel C, Koot HM (2011) Observed interactions indicate protective effects of relationships with parents for referred adolescents. J Res Adolesc 21:569–575. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00703.x

Abaied JL, Rudolph KD (2010) Parents as a resource in times of stress: interactive contributions of socialization of coping and stress to youth psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:273–289. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9364-7

Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ (2008) Reducing early smokers’ risk for future smoking and other problem behavior: insights from a five-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health 43:394–400. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.004

Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS (2008) Protective factors and the development of resilience in the context of neighborhood disadvantage. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36:887–901. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9220-1

Salzinger S, Rosario M, Feldman RS, Ng-Mak DS (2011) Role of parent and peer relationships and individual characteristics in middle school children’s behavioral outcomes in the face of community violence. J Res Adolesc Off J Soc Res Adolesc 21:395–407. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00677.x

Taylor KW, Kliewer W (2006) Violence exposure and early adolescent alcohol use: an exploratory study of family risk and protective factors. J Child Fam Stud 15:201–215. doi:10.1007/s10826-005-9017-6

Yonas MA, Lewis T, Hussey JM et al (2010) Perceptions of neighborhood collective efficacy moderate the impact of maltreatment on aggression. Child Maltreat 15:37–47. doi:10.1177/1077559509349445

Kotch JB, Smith J, Margolis B et al (2014) Does social capital protect against the adverse behavioural outcomes of child neglect? Child Abuse Rev 23:246–261. doi:10.1002/car.2345

Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Tach LM et al (2009) The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on british children growing up in deprivation: a developmental analysis. Dev Psychol 45:942–957. doi:10.1037/a0016162

Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, Bauermeister JA (2012) A longitudinal analysis of cumulative risks, cumulative promotive factors, and adolescent violent behavior. J Res Adolesc Off J Soc Res Adolesc 22:542–555. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00786.x

Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, Urzua S (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J Labor Econ 24:411–482. doi:10.3386/w12006

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Angela Duckworth, PhD, Adrian Raine, PhD, and Lisa Schwartz, PhD for reading and commenting on a previous draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brumley, L.D., Jaffee, S.R. Defining and distinguishing promotive and protective effects for childhood externalizing psychopathology: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 803–815 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1228-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1228-1