Abstract

Purpose

Stressful childhood experiences (SCE) are associated with many different health outcomes, such as psychiatric symptoms, physical illnesses, alcohol and drug abuse, and victimization experiences. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people are at risk to be victims of SCE and show higher prevalence of SCE when compared with heterosexual controls.

Methods

This review analyzed systematically 73 articles that addressed different types of SCE in sexual minority populations and included items of household dysfunction. The samples included adults who identified either their sexual orientation as non-heterosexual or their gender identity as transgender.

Results

The studies reported childhood sexual abuse (CSA), childhood physical abuse (CPA), childhood emotional abuse (CEA), childhood physical neglect, and childhood emotional neglect. Items of household dysfunction were substance abuse of caregiver, parental separation, family history of mental illness, incarceration of caregiver, and witnessing violence. Prevalence of CSA showed a median of 33.5 % for studies using non-probability sampling and 20.7 % for those with probability sampling, the rates for CPA were 23.5 % (non-probability sampling) and 28.7 % (probability sampling). For CEA, the rates were 48.5 %, non-probability sampling, and 47.5 %, probability sampling. Outcomes related to SCE in LGBT populations included psychiatric symptoms, substance abuse, revictimization, dysfunctional behavioral adjustments, and others.

Conclusions

LGBT populations showed high prevalence of SCE. Outcomes related to SCE ranged from psychiatric symptoms and disorders to physical ailments. Most studies were based in the USA. Future research should aim to target culturally different LGBT population in the rest of the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stressful childhood experiences (SCE) have gained more attention over the last years. In a landmark study, Felitti et al. [1] analyzed the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in large Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) samples [n = 9,508; ACE study]. The authors focused on adverse experiences such as childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse and psychological abuse, physical and emotional neglect. Additionally, they introduced the concept of household dysfunction including substance abuse and mental illness of the caregiver, violent treatment of mother or stepmother, separation from caregiver, and criminal behavior in the family. Rates, in this large HMO sample in California, ranged from 3.4 % (criminal behavior in the household) to 25.6 % (substance abuse in the household). In addition, they showed that exposure to any ACE increased the risk of being exposed to any additional experience by up to 80 % and the probability of more than two additional exposures by up to 54.5 % [1, 2]. Other groups have replicated the results found in the ACE study; O’Connor et al. [3] showed that these ACE were connected, with taking place in clusters, and not isolated experiences. The ACE study group also analyzed health risk factors and disease conditions showing a strong dose–response relationship between ACE and these outcomes [1]. In community samples as well as psychiatric populations, increasing events of ACE correlated with higher prevalence of current smoking [4], severe obesity [5], increased head injuries, and medical emergency room visits [6]. Additional studies connected health conditions, such as ischemic heart disease [5], cancer [7], stroke, emphysema, diabetes [8], skeletal fractures, and hepatitis [9] with abusive experiences during childhood. Moreover, problems with alcohol [10] and illicit drug use [9], as well as promiscuity and history of sexually transmitted diseases [11], were shown to be related to SCE. Furthermore, SCE were strongly associated with mental health issues. Other studies showed associations with affective disorders [12, 13], anxiety, and panic symptoms [12], suicide attempts [13], and psychotic symptoms [14–16].

The literature about victimization experiences in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people has been a more recent focus of research. An early comprehensive study on lesbians showed that 37 % had been physically abused as a child or adult, 32 % had been raped or sexually attacked, and 19 % had been involved in incestuous relationships while growing up [17]. Another study suggested that LGBT people had a higher prevalence of rape below the age of 18 than their heterosexual counterpart [18]. Doll et al. [19] reported high rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) in both, bisexual and homosexual men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Similarly, Tomeo et al. [20] demonstrated increased rates of CSA in a homosexual people, when compared to heterosexual people. A US population-based survey reported higher rates of parental maltreatment during childhood for homosexual and bisexual men and women than for heterosexual adults [21]. Also, several studies analyzing lesbian populations found high rates of childhood and adulthood sexual and physical abuse [22, 23]. A systematic review focusing mainly on sexual assault (childhood sexual assault, lifetime sexual assault, intimate partner sexual assault, and adult sexual assault) showed a 22.7 % median prevalence for childhood sexual assault in men and a median of 34.5 % for women in adult sexual minority populations [24]. In high-risk youth, high rates of SCE were found [25]. A meta-analysis also showed high rates of abuse experiences in sexual minority youths [26]. Transgender people in particular were at high risk for being victims of violence. Stereotypes and negative depiction in media and society led to hate crimes and so-called trans bashing (aggression against transgender people), which put this population at stake for victimization [27]. LGBT populations were also at high risk for diverse health conditions, such as sleep disturbances, anxiety and depressive symptoms, gastrointestinal and chronic rheumatic diseases [28]. They were also found to be susceptible for health disparities based on discrimination, family disapproval, social rejection, and violence [26, 29].

The objective of this systematic review was to gather the growing information on rates of SCE in LGBT populations. The analysis included rates of childhood sexual abuse (CSA), childhood physical abuse (CPA), childhood emotional abuse (CEA), childhood physical neglect (CPN), and childhood emotional neglect (CEA). In addition, the review focused on items of household dysfunction such as drug abuse and alcohol abuse in the household, witnessing of physical and sexual violence, as well as arrest histories within the family. Health outcomes related to these severe childhood experiences were analyzed. For the purpose of this review, we defined the individual abuse experiences according to the Histories of Physical and Sexual Abuse Questionnaire [30] and the items of household dysfunction according to the ACE questionnaire [1].

Method

Search strategy

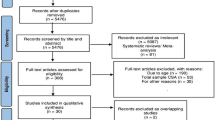

This systematic review was structured following the guidelines and checklist proposed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement [31, 32]. The review was registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42014007034 [33].

The literature search was based on search engines including MEDLINE (Ovid), PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PsycNet (includes PsycINFO, PsycBOOKS, PsycARTICLES, PsycTESTS), between 01/01/1990 and 12/31/2013. The advanced searches for the category sexual orientation or gender identity included the search terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, homosexual, men who have sex with men and for the category of stressful childhood experiences the terms childhood abuse, childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, childhood emotional abuse, childhood physical neglect, childhood emotional neglect, household dysfunction, and witnessing.

The accepted languages were English, German, French, Italian, and Spanish. Data were included that had been published in peer-reviewed journals, presented at conferences, as poster presentations or, if non-published, the data were provided from the researchers directly. We also reviewed reference lists of important key publications to incorporate the identified studies in our review. In order to avoid missing data due to publication bias, such as the file drawer effect [34], we contacted the corresponding authors of the enclosed publications via email, requesting access to possible unpublished data, data presented in conferences or on poster presentations. Out of the 58 contacted authors, 26 responded adding 17 more articles to the initial records, as well as unpublished data or confirming that they do not possess any additional published or unpublished data.

Screening and selection procedure

The searches were performed independently by two of the authors (Andres R. Schneeberger, Michael F. Dietl). The flow diagram depicted in Fig. 1 shows the process of study selection. The first step after the search included scanning for duplicates based on the summary information (authors, title, and journal). After the duplicates had been removed, the abstracts were screened for the following inclusion criteria: (a) adult samples (18 years and older); (b) participants identified their sexual orientation as non-heterosexual or their gender identity as transsexual, transgender or non-male, non-female; (c) analysis of severe childhood experiences before the age of 18. Qualitative studies were accounted for if they included a quantitative analysis of the SCE. If the inclusion criteria could not be assessed from the abstract, the entire article was reviewed. The next step included full-text assessment of the remaining articles for the following exclusion criteria: (1) the article had to have the approval of an internal review board or an ethics committee; (2) the adverse experience had to occur before the age of 18; (3) if prevalence was not presented or data did not allow for computation of these rates, and the authors could not be contacted for the raw data, the article was excluded.

Data extraction

The initial results of the database searches were exported into word files and screened using search functions. Prevalence was calculated if necessary to present them in a uniform fashion by determining the mean where possible. In order to get the prevalence for males, females, and total participants, these rates were calculated using the rule of proportion. If present, outcome variables were noted and grouped into five categories: psychiatric symptoms, substance abuse, dysfunctional behavioral adjustments, revictimization, and others. All studies except six analyzed at least one outcome variable related to SCE.

Results

The list of all analyzed articles is presented in Table 1. The total sample size, including sexual minority and majority individuals, is reported as well as the subsample of the LGBT target populations analyzed in this review. The data from Hequembourg et al. [35] were obtained from the abstract of a poster presentation. Two research groups provided us with additional unpublished data in order to calculate the prevalence [25, 36]. Twelve studies focused on lesbian subjects only; one study targeted homosexual women and one included a category called mostly heterosexual women; eight studies include lesbian and bisexual women in their analysis; eleven studies focused on MSM; eleven manuscripts targeted gay and bisexual males; transgender subjects were included in three studies, all of which analyze MTF but only one included FTM individuals. The rest focused mainly on compound populations of lesbian, gay, MSM, and bisexual individuals. Only one study [37] fulfilled the criteria of a prospective study, including a baseline assessment and reassessment at future measuring points. Out of all the studies, 22 had a higher external validity as they analyzed entire populations and not only convenience samples. One qualitative study was included because SCE was analyzed in a quantitative fashion [38]. Thirty-seven studies used paper questionnaires, while 23 chose a face-to-face interview to gather the information. Eight studies used a phone interview and the rest relied on online questionnaire, computer interview, or mixed forms of interviewing. Sixty-four out of 73 analyzed studies were based in the United States of America and Puerto Rico, while three were European-based, two from Germany [39, 40], and one from Italy [41]. In addition, two studies originated from Canada [42, 43], one from China [44], one from Turkey [36], one from Brazil [45], and one from Australia [46]. LGBT population sample sizes ranged from 12 to 4,295 participants with a median of 446 analyzed sexual minority subjects. Seventy studies (95.9 %) analyzed CSA; however, only 33 (45.2 %) focused on CPA and 11 (15.1 %) on CEA. Experiences of CEN and CPN were studied in three cases. Household dysfunction items were included five times.

The definitions used for CSA varied throughout the studies and ranged from questions about having had a sexual experience that felt abusive to specific questions addressing sexual touching, oral sex, and penetration. The age cutoff ranged from ages 14 to 18. The studies also used different definitions for CPA, extending from slapping to using an object that hurt or burned the victim to the point that medical care was needed. CEA variables were defined as psychological abuse including humiliation, belittling but also threatening behavior. Neglect variables such as CPN and CEN addressed the lack of care provided by the responsible parent or caregiver, this included not providing adequate food and shelter or psychological and emotional support.

Several possible biases at the level of individual studies were identified. Some of the studies used probability samples while others did not. In addition, different populations were analyzed including clinical and general populations, as well as specialized subgroups, such as HIV risk populations [47–55], call boys [56], and different ethnic groups (Afro-American [38, 57], Native-American [58], Latino [59–62], etc.). Most studies had a retrospective design; the information regarding ACE were based on the participants’ recall. In order to address possible biases, the studies were stratified by probability versus non-probability samples. The median prevalence for total CSA was 20.7 % for probability studies and 33.5 % for non-probability studies. This difference in CSA according to sampling type had been described previously [24]. CPA showed the following median prevalence: 28.7 % for probability and 23.5 % for non-probability samples. CEA prevalence accounted with 47.5 % for probability and 48.5 % non-probability samples. Regarding the interviewing method, the studies using questionnaires presented a median prevalence for CSA of 26.6 versus 31.1 % for the rest of the interviewing strategies. CPA rates in the questionnaire group reached a median of 24.0 versus 26.9 % for all other interviewing methods. CEA rates showed no significant difference between questionnaires (48.7 %) and other interviewing methods (43.7 %). The median value for CEA in the questionnaire group was 48.7 % while the remaining studies had a median prevalence of 43.7 %.

Prevalence of stressful childhood experiences

Table 2 lists the categories CSA, CPA, CEA, CPN, and CEA by gender. Prevalence for CSA ranged between 9.1 and 67 % for men (median: 22.0 %), and 0 to 68.0 % for women (median: 32.2 %). Rates for CPA in men were established between 2.5 and 70.6 % (median: 22.3 %). The rates for women were between 2.6 and 38.0 % for CPA (median: 26.6 %). CEA rates for men were represented between 4.0 and 52.6 % (median: 45.0 %). For women, the range was between 2.0 and 60.8 % (median: 45.5 %). Only four studies [37, 39, 63, 64] presented prevalence for CPN, of which Roberts et al. [63] showed that the prevalence for men was 10.0 % and for women 10.5 %. Kersting et al. [39] focused on transgender (MTF and FTM) individuals yielding a prevalence for CPN of 51.2 %. Alvy et al. [64] interviewed a population of lesbian and bisexual women and found CPN rates of 14.1 %. In a population of men and women with same-sex relationships, the prevalence of CPN varied from 4.0 to 6.3 % for men and from 2.0 to 7.3 % for women [37]. Research targeting rates of CEN were present in two studies, Krahé et al. [40] analyzed a male population (prevalence: 30.0 %) and Kersting et al. [39] focused on a transgender population (CEN prevalence: 78.0 %). The items of household dysfunction were assessed in five studies. Roberts et al. [65] showed that in a cohort of women, 19.0 % of positive family histories of drug abuse and 49.0 % positive family histories of alcoholism, while Hughes et al. [66] accounted for 36.0 % of parental drinking problems. Roberts et al. [63] reported the prevalence of witnessing violence (17.7 %) during childhood and Zietsch et al. [46] described risky family environments (41.4 %), which consisted of an operationalized scale including unpleasant disagreements with parents, not being close to parents, parents fighting with each other, and alcohol consumption of parent. In a recent study Andersen, Blosnich [67] addressed several items of household dysfunction in a gay and lesbian population: household mental illness (26.5 %), household substance abuse (46.5 %) incarcerated household member (7.3 %), parental separation or divorce (25.8 %), and exposure to domestic violence (24.1 %). Twenty-eight studies (Table 1) had a heterosexual control group. The median rates for CSA in the heterosexual group were 17.0 %, in the sexual minority groups that had a control group, the median CSA rate was 35.5 %. CPA was present in 11.0 % of heterosexual participants and 27.0 % of the compared non-heterosexual population. The median prevalence for CEA was 29.6 % in the control group versus 46.4 % of the analyzed LGBT groups.

Health outcomes

There were a vast variety of analyzed outcomes that the authors related to the aforementioned SCE. The outcome variables are listed in Table 3 and grouped into five different categories: psychiatric symptoms, substance abuse, dysfunctional behavioral adjustments, revictimization, and others.

Psychiatric symptoms

The most commonly described psychiatric outcomes were depressive symptoms [47, 54, 66, 68, 69] and suicidal symptoms [36, 47, 69, 70]. Four studies focused on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder [58, 68, 71, 72]. Anxiety related health outcomes were the focus of three publications [54, 58, 71]. Feldman and Meyer [73] showed correlations between CSA and symptoms of eating disorders in a population of gay and bisexual men. Two studies [41, 58] analyzed compound psychiatric symptomatology using the Global Severity Index [74, 75].

Substance abuse

Out of the 18 studies focusing on substance abuse related to SCE, 14 analyzed alcohol use, abuse, dependence or other alcohol-related problems [42, 54, 58, 60, 65, 76–83]. Four studies showed correlations between CSA and illicit substance use [47, 48, 51, 58]. Bartholow et al. [47] and Kalichman et al. [51] reported connections between CSA and tobacco use, while Matthews et al. [84] reported age of smoking onset and current smoking status to be mediators between CPA and self-reported health status.

Dysfunctional behavioral adjustment

All of the studies analyzing dysfunctional behavioral adjustments focused on the correlation between CSA and increased high-risk sexual behavior [49–52, 54, 60, 61, 66, 85–88]. Carballo-Dieguez et al. [45] were not able to replicate these findings in a Brazilian population of MSM and transgender people. Robohm et al. [88] were the only authors to study a female population.

Revictimization

Adult revictimization experiences included sexual, physical, and emotional abuse in adulthood. Seven studies analyzed female populations [76, 77, 89–93] and eight studies focused their attention on male subjects [35, 40, 51, 90, 91, 94–96].

Other outcomes

Two studies reported an association between CSA and obesity; women with histories of CSA were more likely to be obese [97, 98]. SCE showed to be correlated with the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in men and women [53, 99]. Weingourt [100] described that women with histories of CSA described less sexual satisfaction in their relationships. Wilson and Widom [37] stated that men and women with histories of CSA were more likely to ever having had same-sex sexual partners.

Discussion

The assessed studies span over a time period of more than 20 years. Most studies, however, have been conducted in the last 5–10 years. Most studies originated from the United States of America (US) and Puerto Rico. Therefore, a generalization of the presented data is mostly limited to the US and not applicable to the rest of the world. Considering the vast variety of examined populations, cultures, subcultures, ethnicities, and groups, the definition of what is considered an abusive experience itself varies significantly [101].

Prevalence of stressful childhood experiences

Most studies addressed CSA. Some of the variability of prevalence might be explained by different sampling methods and different definitions of CSA. Definitions ranged from any contact sexual abuse to rape. Fifteen studies compared the rates of CSA with a heterosexual control group, showing a higher prevalence for the minority group (18.0 vs. 35.5 %). This supports prior studies [18] that postulated that sexual minority populations had a higher risk of SCE. Race or ethnicity showed to have an impact on CSA prevalence; in that, African-American men in a cohort of internet escorts were eight times more likely to report CSA than Caucasian men [56]. In contrast to CSA, the other two abuse variables CPA and CEA showed less variation related to the sampling type. When compared to majority sexual control groups, the higher rates for minority sexual population were evident (CPA: 11.0 vs. 20.0 %; CEA: 23.6 vs. 38.1 %). It remains unclear as to why only CSA showed different prevalence related to the sampling method. Studies have shown that stigmatization and recall bias might lead to underreporting in CSA [102]. Population-based sampling in contrast to population recruited at specific events might also be more likely to reach people that were not open about their sexual orientation or gender identity; therefore, more inhibited to openly address histories of CSA. In addition, the interviewing method had an impact on the prevalence. The literature on this issue is inconclusive [103], some authors suggested that in regards to CSA disclosure rates tended to be higher in face-to-face interviews as opposed to questionnaires [104], others have found no differences between the methods of administration [105]. General consensus seems to be that in the psychiatric population trauma rates tend to be underreported [106].

CPA also showed a variation in terms of its definition, ranging from being hit so hard that it left bruises to being punished with an object, which required hospitalization. Neglect variables were only addressed in two studies, one analyzing CEN and CEA in a population of transgender people and the other targeting men only. One study described family histories of alcoholism and drug abuse [65]; Roberts et al. [63] also presented rates of witnessing domestic violence. Another study group analyzed risky family environment [46]. The paucity of data regarding variables of household dysfunction in LGBT population does not permit to make any conclusions or generalizations on the prevalence of SCE or any outcomes related to SCE, about individuals with non-heterosexual orientation. The importance of cumulative traumatic experiences has been highlighted by several studies [1, 6, 107], but no study addressed this topic in LGBT populations.

Health outcomes

Psychiatric symptoms

The reviewed studies showed associations between SCE and psychiatric symptoms, confirming that the results of other study samples [16], HMO samples [12], and psychiatric samples [6, 14] are replicable in LGBT populations. The higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms might be related to higher rates of SCE in this population. However, it needs to be taken into consideration that the stress related to living as a sexual minority can lead to psychiatric symptoms on its own [28]. In addition, the lack of data regarding cumulative exposures might modify the results.

Substance abuse

The studies addressed mainly CSA without analyzing other abuse forms. Studies focusing on female participants examined more alcohol-related problems such as hazardous drinking, alcohol abuse, and alcohol dependence. Men-focused analyses targeted drugs such as cocaine, crack, amyl nitrate, crystal methamphetamine, Ecstasy, and Special K (ketamine). These results expanded prior knowledge that SCE were linked to adulthood substance use [9, 10]. In the absence of prospective studies, these associations are a lack of proof that substance abuse is causally linked to CSA.

Dysfunctional behavioral adjustments

Felitti et al. [1] explained that individuals with histories of SCE might adopt high-risk behavior in an unsuccessful attempt to cope with the social, emotional, and cognitive impairments caused by the trauma. The reviewed studies were able to demonstrate similar behavioral outcomes in traumatized LGBT populations. Similar to substance abuse outcome variables, the behavioral outcomes were mainly related to CSA. One study focusing on MSM and transgender people was not able to replicate these results [45]. The authors speculated that in Brazil different cultural perceptions regarding sex with an older partner might lead some participants to experience the sexual act as non-abusive.

Revictimization

On the one hand, some of the described studies were able to show associations between different forms of SCE and later victimization. On the other hand, some of the studies demonstrated higher revictimization rates in sexual minority populations as compared to heterosexual control groups. It is possible that SCE in LGBT populations could increase environmental and personal stress on the individual. In return, this can lead to high-risk behavior [6] putting the individual at risk for victimization. Openly identifying as LGBT might place the individual at higher risk for victimization [108, 109]. Considering the fact that the analyzed studies did not have a longitudinal design, no causal connection could be made.

Other outcomes

This review shows that SCE in an LGBT population were related to a vast array of negative outcomes ranging from psychiatric symptoms to physical health issues. The association between SCE and obesity in a population of lesbian women or STD in both gay and lesbian people could be explained with maladaptive behavior leading to health risks [1]. Independent of the pathway, these results suggest that findings in other populations such as the health organization sample described by Felitti et al. [1] are supported and amplified in a sexual minority population.

Limitations

The analyzed population was comprised of different subpopulations, different types of sexual orientation and gender identities, including females, males, and transgender people. Studies with heterogeneous study samples reported a variety of results, which made a clear synthesis of the prevalence and health outcomes difficult. As shown in this review, there were phenomena specific to some subgroups and not to others. The differentiation between sexual minority and sexual majority population was rather speculative in nature; in this review, for example, we did include people who consider themselves mostly heterosexual into the sexual minority group [99]. The analyzed populations were 18 years or older and included only recalled data. With recalled data, non-disclosure of childhood adversities could influence the presented data and produce false negative results, depending on abuse severity and the age at which the abuse was experienced [110]. For an analysis of CSA and CPA in children and adolescents, we would like to refer to the meta-analysis of Friedman et al. [26]. We did not limit our analysis to studies using heterosexual control groups. This leads to a limited validity regarding prevalence when compared to a general population. The focus of this review was on the frequency of SCE and not on the intensity, not many studies addressed this important aspect of SCE [111]. Due to the scarcity of literature, different types of sampling methods were included in this review, involving probability and non-probability methods. Methodological differences might account for some of the prevalence variability. Definitions of different types of SCE were accepted, including different intensities, frequencies and forms of abuse, which might explain the rather broad range of prevalence. The studies also used different methods of interviewing, ranging from paper questionnaires to face-to-face interviews, which might have affected the results. The anonymity of a questionnaire might be conducive to disclose more information; on the other hand, interviews conducted by trained clinicians might allow for a trusting relationship and safe environment, where the person might be able to disclose traumatic experiences. Future studies should aim to use more standardized instruments to assess SCE in order to have better options for comparison. None of the studies addressed cumulative trauma, preventing any statement about aggregate phenomena related to complex forms of trauma in this population.

Conclusions

SCE, including childhood abuse and household dysfunction, showed high prevalence in LGBT populations. Outcomes related to SCE were multiple and ranged from psychiatric symptoms and disorders to physical ailments. Minority sexual populations were also at higher risk for alcohol and substance abuse. Overall LGBT populations were vulnerable to victimization experiences throughout their lives.

Most studies were based in the United States of America and Puerto Rico. It is possible that admitting to have a non-heterosexual orientation or different gender identity in a third world country might place the individual at risk. Performing studies in these countries might be very difficult as it is virtually impossible to recruit people to participate in this kind of research. Despite these difficulties, future research should aim to target culturally different LGBT population in the rest of the world. Due to difficulties recruiting LGBT participants from general population samples, most studies rely on convenience sampling. This method contributes important results to the understanding of SCE in LGBT population. However, prospective probability studies have the advantage to explain causality in the described phenomena. Further research should try to implement these methods to advance the knowledge of minority sexual population. The noteworthy lack of studies on the transgender population points out the urgent need for more research. Transgender people are among the most vulnerable members of our society and therefore need to be supported. In sum, this review shows that LGBT populations are often subject to SCE and suffer throughout adulthood from many negative health outcomes. Health care providers should be attentive to the possibility of SCE in their LGBT clients, and the potential long-term negative impacts on both physical and mental health, making trauma informed care a necessity in the health care delivery system of this population. On a public health level, efforts should be made to sensitize the LGBT and general population to SCE in order to prevent further abuse. Policy and lawmakers should take these facts into consideration and aim to protect this vulnerable population from maltreatment.

References

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ (2003) The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse Negl 27(6):625–639

O’Connor C, Finkbiner C, Watson L (2012) Adverse childhood experiences in Wisconsin: findings from the 2010 behavioral risk factor survey. http://wichildrenstrustfund.org/index.php?section=adverse-childhood. Accessed 01/27/2014

Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Giles WH, Williamson DF, Giovino GA (1999) Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. J Am Med Assoc 282(17):1652–1658

Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF (2004) Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation 110(13):1761–1766. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F

Schneeberger AR, Muenzenmaier KH, Battaglia J, Castille D, Link BG (2012) Childhood abuse, head injuries, and use of medical emergency services in people with severe mental illness. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 21(5):570–582. doi:10.1080/10926771.2012.678468

Brown DW, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Malarcher AM, Croft JB, Giles WH (2010) Adverse childhood experiences are associated with the risk of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 10:20. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-20

Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Gu D, Dube SR, Felitti VJ (2007) Adverse childhood experiences and smoking persistence in adults with smoking-related symptoms and illness. Perm J 11(2):5–13

Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF (2003) Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 111(3):564–572

Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB (2002) Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addict Behav 27(5):713–725

Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Nordenberg D, Marchbanks PA (2000) Adverse childhood experiences and sexually transmitted diseases in men and women: a retrospective study. Pediatrics 106(1):E11

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH (2006) The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256(3):174–186. doi:10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH (2001) Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 286(24):3089–3096

Rosenberg SD, Lu W, Mueser KT, Jankowski MK, Cournos F (2007) Correlates of adverse childhood events among adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Serv 58(2):245–253. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.58.2.245

Schafer I, Fisher HL (2011) Childhood trauma and psychosis—what is the evidence? Dialog Clin Neurosci 13(3):360–365

Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, Ross CA (2005) Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112(5):330–350. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x

Bradford J, Ryan C, Rothblum ED (1994) National lesbian health care survey: implications for mental health care. J Consult Clin Psychol 62(2):228

Tjaden P, Thoennes N, Allison CJ (1999) Comparing violence over the life span in samples of same-sex and opposite-sex cohabitants. Violence Vict 14(4):413–425

Doll LS, Joy D, Bartholow BN, Harrison JS, Bolan G, Douglas JM, Saltzman LE, Moss PM, Delgado W (1992) Self-reported childhood and adolescent sexual abuse among adult homosexual bisexual men. Child Abuse Negl 16(6):855–864

Tomeo ME, Templer DI, Anderson S, Kotler D (2001) Comparative data of childhood and adolescence molestation in heterosexual and homosexual persons. Arch Sex Behav 30(5):535–541

Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM (2002) Reports of parental maltreatment during childhood in a United States population-based survey of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual adults. Child Abuse Negl 26(11):1165–1178

Hughes TL, Haas AP, Razzano L, Cassidy R, Matthews A (2000) Comparing lesbians’ and heterosexual women’s mental health: a multi-site survey. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 11(1):57–76

Lehmann JB, Lehmann CU, Kelly PJ (1998) Development and health care needs of lesbians. J Women’s Health 7(3):379–387

Rothman EF, Exner D, Baughman AL (2011) The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the United States: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 12(2):55–66. doi:10.1177/1524838010390707

Kecojevic A, Wong CF, Schrager SM, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Iverson E, Lankenau SE (2012) Initiation into prescription drug misuse: differences between lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and heterosexual high-risk young adults in Los Angeles and New York. Addict Behav 37(11):1289–1293. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.006

Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, Wei C, Wong CF, Saewyc EM, Stall R (2011) A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health 101(8):1481

Hill DB (2003) Genderism, transphobia, and gender bashing: a framework for interpreting anti-transgender violence. In: Wallace BC, Carter RT (eds) Understanding and dealing with violence: a multicultural approach. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, pp 113–137. doi:10.4135/9781452231723

Schneeberger AR, Rauchfleisch U, Battegay R (2002) Psychosomatische Folgen und Begleitphänomene der Diskriminierung am Arbeitsplatz bei homosexuellen Menschen. [Psychosomatic consequences and phenomena of discrimination at work against people with homosexual orientation]. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und. Psychiatrie 153(3):137–143

Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Kinchen S, Chyen D, Harris WA, Wechsler H, Centers for Disease C, Prevention (2011) Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12–youth risk behavior surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. Morb Mortal Wkl Rep Surveill Summ 60(7):1–133

Meyer IH, Muenzenmaier K, Cancienne J, Struening E (1996) Reliability and validity of a measure of sexual and physical abuse histories among women with serious mental illness. Child Abuse Negl 20(3):213–219

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux P, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 151(4):W-65–W-94

PROSPERO (2013) International prospective register of systematic reviews. University of York. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. Accessed 01/05/2014

Rosenthal R (1979) The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull 86(3):638

Hequembourg A, Livingston J, Parks K (2013) Lifetime sexual victimiza lifetime sexual victimization risks among sexual minority men. Paper presented at the The 36th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Orlando, FL

Eskin M, Kaynak-Demir H, Demir S (2005) Same-sex sexual orientation, childhood sexual abuse, and suicidal behavior in university students in Turkey. Arch Sex Behav 34(2):185–195

Wilson HW, Widom CS (2010) Does physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect in childhood increase the likelihood of same-sex sexual relationships and cohabitation? A prospective 30-year follow-up. Arch Sex Behav 39(1):63–74. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9449-3

Fields S (2008) Childhood sexual abuse in black men who have sex with men: results from three qualitative studies. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol 14(4):385–390

Kersting A, Reutemann M, Gast U, Ohrmann P, Suslow T, Michael N, Arolt V (2003) Dissociative disorders and traumatic childhood experiences in transsexuals. J Nerv Ment Dis 191(3):182–189. doi:10.1097/01.NMD.0000054932.22929.5D

Krahé B, Scheinberger-Olwig R, Schütze S (2001) Risk factors of sexual aggression and victimization among homosexual men. J Appl Soc Psychol 31(7):1385–1408. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02679.x

Bandini E, Fisher AD, Ricca V, Ristori J, Meriggiola MC, Jannini EA, Manieri C, Corona G, Monami M, Fanni E, Galleni A, Forti G, Mannucci E, Maggi M (2011) Childhood maltreatment in subjects with male-to-female gender identity disorder. Int J Impot Res 23(6):276–285. doi:10.1038/ijir.2011.39

Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Shoveller JA, Chan K, Martindale SL, Schilder AJ, Botnick MR, Hogg RS (2003) Non-consensual sex experienced by men who have sex with men: prevalence and association with mental health. Patient Educ Couns 49(1):67–74

Stanley JL, Bartholomew K, Oram D (2004) Gay and bisexual men’s age-discrepant childhood sexual experiences. J Sex Res 41(4):381–389. doi:10.1080/00224490409552245

Chen G, Li Y, Zhang B, Yu Z, Li X, Wang L, Yu Z (2012) Psychological characteristics in high-risk MSM in China. BMC public health 12:58. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-58

Carballo-Dieguez A, Balan I, Dolezal C, Mello MB (2012) Recalled sexual experiences in childhood with older partners: a study of Brazilian men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender persons. Arch Sex Behav 41(2):363–376. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9748-y

Zietsch BP, Verweij KJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Martin NG, Nelson EC, Lynskey MT (2012) Do shared etiological factors contribute to the relationship between sexual orientation and depression? Psychol Med 42(3):521–532. doi:10.1017/S0033291711001577

Bartholow BN, Doll LS, Joy D, Douglas JM Jr, Bolan G, Harrison JS, Moss PM, McKirnan D (1994) Emotional, behavioral, and HIV risks associated with sexual abuse among adult homosexual and bisexual men. Child Abuse Negl 18(9):747–761

Brennan DJ, Hellerstedt WL, Ross MW, Welles SL (2007) History of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk behaviors in homosexual and bisexual men. Am J Public Health 97(6):1107–1112. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.071423

Carballo-Dieguez A, Dolezal C (1995) Association between history of childhood sexual abuse and adult HIV-risk sexual behavior in Puerto Rican men who have sex with men. Child Abuse Negl 19(5):595–605

Halkitis PN, Siconolfi D, Fumerton M, Barlup K (2008) Risk bases in childhood and adolescence among HIV-negative young adult gay and bisexual male barebackers. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 20(4):288–314. doi:10.1080/10538720802310709

Kalichman SC, Gore-Felton C, Benotsch E, Cage M, Rompa D (2004) Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. J Child Sex Abuse 13(1):1–15. doi:10.1300/J070v13n01_01

Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, O’Cleirigh C, Chesney MA, Coates TJ, Koblin BA (2009) Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk–taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 51(3):340

Sweet T, Welles SL (2012) Associations of sexual identity or same-sex behaviors with history of childhood sexual abuse and HIV/STI risk in the United States. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 59(4):400–408

Welles SL, Baker AC, Miner MH, Brennan DJ, Jacoby S, Rosser BS (2009) History of childhood sexual abuse and unsafe anal intercourse in a 6-city study of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 99(6):1079–1086

Jinich S, Paul JP, Stall R, Acree M, Kegeles S, Hoff C, Coates TJ (1998) Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk-taking behavior among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2(1):41–51

Parsons JT, Bimbi DS, Koken JA, Halkitis PN (2005) Factors related to childhood sexual abuse among gay/bisexual male internet escorts. J Child Sex Abuse 14(2):1–23

Benoit E, Downing MJ Jr (2013) Childhood sexual experiences among substance-using non-gay identified Black men who have sex with men and women. Child Abuse Negl 37:679

Balsam KF, Huang B, Fieland KC, Simoni JM, Walters KL (2004) Culture, trauma, and wellness: a comparison of heterosexual and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and two-spirit Native Americans. Cult Divers Ethn Minority Psychol 10(3):287

Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Pollack LM, Paul JP, Catania JA (2005) Higher prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among Latino men who have sex with men than non-Latino men who have sex with men: data from the urban men’s health study. Child Abuse Negl 29(3):285–290. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.09.003

Dolezal C, Carballo-Dieguez A (2002) Childhood sexual experiences and the perception of abuse among Latino men who have sex with men. J Sex Res 39(3):165–173. doi:10.1080/00224490209552138

Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Diaz R (2009) Childhood sexual abuse and the sociocultural context of sexual risk among adult Latino gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health 99(Suppl 2):S432–S438. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.138925

Wong CF, Weiss G, Ayala G, Kipke MD (2010) Harassment, discrimination, violence, and illicit drug use among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ 22(4):286–298. doi:10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.286

Roberts AL, Austin SB, Corliss HL, Vandermorris AK, Koenen KC (2010) Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Public Health 100(12):2433–2441. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.168971

Alvy LM, Hughes TL, Kristjanson AF, Wilsnack SC (2013) Sexual identity group differences in child abuse and neglect. J Interpers Violence 28(10):2088–2111

Roberts SJ, Grindel CG, Patsdaughter CA, DeMarco R, Tarmina MS (2004) Lesbian use and abuse of alcohol: results of The Boston Lesbian Health Project II. Subst Abuse 25(4):1–9

Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA (2007) Childhood risk factors for alcohol abuse and psychological distress among adult lesbians. Child Abuse Negl 31(7):769–789

Andersen JP, Blosnich J (2013) Disparities in adverse childhood experiences among sexual minority and heterosexual adults: results from a multi-state probability-based sample. PLoS ONE 8(1):e54691

Gold SD, Feinstein BA, Skidmore WC, Marx BP (2011) Childhood physical abuse, internalized homophobia, and experiential avoidance among lesbians and gay men. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 3(1):50

Matthews AK, Hughes TL, Johnson T, Razzano LA, Cassidy R (2002) Prediction of depressive distress in a community sample of women: the role of sexual orientation. Am J Public Health 92(7):1131–1139

Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE (2009) Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. Am J Orthopsychiatry 79(4):511–521. doi:10.1037/a0017163

Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B, Circo E (2010) Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 78(4):459–468. doi:10.1037/a0018661

Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB (2012) Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. Am J Public Health 102(8):1587–1593. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530

Feldman MB, Meyer IH (2007) Childhood abuse and eating disorders in gay and bisexual men. Int J Eat Disord 40(5):418–423. doi:10.1002/eat.20378

Derogatis LR, Savitz KL (1999) The SCL-90-R, Brief Symptom Inventory, and Matching Clinical Rating Scales. In: The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ, US, pp 679–724

Derogatis LR, Spencer P (1993) Brief symptom inventory: BSI. Pearson Upper Saddle River, NJ

Drabble L, Trocki KF, Hughes TL, Korcha RA, Lown AE (2013) Sexual orientation differences in the relationship between victimization and hazardous drinking among women in the National Alcohol Survey. Psychol Addict Behav 27:639

Gilmore AK, Koo KH, Nguyen HV, Granato HF, Hughes TL, Kaysen D (2013) Sexual assault, drinking norms, and drinking behavior among a national sample of lesbian and bisexual women. Addictive behaviors 39:630

Hequembourg AL, Bimbi D, Parsons JT (2011) Sexual victimization and health-related indicators among sexual minority men. J LGBT Issues Couns 5(1):2–20

Hughes TL (2003) Lesbians’ drinking patterns: beyond the data. Subst Use Misuse 38(11–13):1739–1758

Hughes TL, Szalacha LA, Johnson TP, Kinnison KE, Wilsnack SC, Cho Y (2010) Sexual victimization and hazardous drinking among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Addict Behav 35(12):1152–1156. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.004

Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ (2010) Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction 105(12):2130–2140. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x

McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Xuan Z, Conron KJ (2012) Disproportionate exposure to early-life adversity and sexual orientation disparities in psychiatric morbidity. Child Abuse Negl 36(9):645–655. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.004

Wilsnack SC, Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Bostwick WB, Szalacha LA, Benson P, Aranda F, Kinnison KE (2008) Drinking and drinking-related problems among heterosexual and sexual minority women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 69(1):129–139

Matthews AK, Cho YI, Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Alvy L (2013) The Influence of Childhood Physical Abuse on Adult Health Status in Sexual Minority Women: The Mediating Role of Smoking. Women’s Health Issues 23:e95

Catania JA, Paul J, Osmond D, Folkman S, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang J, Neilands T (2008) Mediators of childhood sexual abuse and high-risk sex among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Child Abuse Negl 32(10):925–940. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.010

Lenderking WR, Wold C, Mayer KH, Goldstein R, Losina E, Seage GR 3rd (1997) Childhood sexual abuse among homosexual men. Prevalence and association with unsafe sex. J Gen Intern Med 12(4):250–253

Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R (2001) Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: the urban men’s health study. Child Abuse Negl 25(4):557–584

Robohm JS, Litzenberger BW, Pearlman LA (2003) Sexual abuse in lesbian and bisexual young women: associations with emotional/behavioral difficulties, feelings about sexuality, and the “coming out” process. J Lesbian Stud 7(4):31–47

Austin SB, Jun HJ, Jackson B, Spiegelman D, Rich-Edwards J, Corliss HL, Wright RJ (2008) Disparities in child abuse victimization in lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the nurses’ health study II. J Women’s Health 17(4):597–606. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0450

Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP (2005) Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(3):477–487. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477

Heidt JM, Marx BP, Gold SD (2005) Sexual revictimization among sexual minorities: a preliminary study. J Trauma Stress 18(5):533–540

Morris JF, Balsam KF (2003) Lesbian and bisexual women’s experiences of victimization: mental health, revictimization, and sexual identity development. J Lesbian Stud 7(4):67–85

Stoddard JP, Dibble SL, Fineman N (2009) Sexual and physical abuse: a comparison between lesbians and their heterosexual sisters. J Homosex 56(4):407–420. doi:10.1080/00918360902821395

Finlinson HA, Robles RR, Colón HM, Lopez MS, del Carmen NM, Oliver-Vélez D, Deren S, Andía JF, Cant JG (2003) Puerto Rican drug users’ experiences of physical and sexual abuse: comparisons based on sexual identities. J Sex Res 40(3):277–285

Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Cheong J, Wright ER (2008) Gay-related development, early abuse and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS Behav 12(6):891–902

Toro-Alfonso J, Rodriguez-Madera S (2004) Domestic violence in Puerto Rican gay male couples: perceived prevalence, intergenerational violence, addictive behaviors, and conflict resolution skills. J Interpers Violence 19(6):639–654. doi:10.1177/0886260504263873

Aaron DJ, Hughes TL (2007) Association of childhood sexual abuse with obesity in a community sample of lesbians. Obesity 15(4):1023–1028. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.634

Smith HA, Markovic N, Danielson ME, Matthews A, Youk A, Talbott EO, Larkby C, Hughes T (2010) Sexual abuse, sexual orientation, and obesity in women. J Women’s Health 19(8):1525–1532. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1763

Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE (2008) Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. Am J Public Health 98(6):1015–1020

Weingourt R (1998) A comparison of heterosexual and homosexual long-term sexual relationships. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 12(2):114–118

Korbin JE (2002) Culture and child maltreatment: cultural competence and beyond. Child Abuse Negl 26(6):637–644

Dill DL, Chu JA, Grob MC, Eisen SV (1991) The reliability of abuse history reports: a comparison of two inquiry formats. Compr Psychiatry 32(2):166–169

Hulme PA (2004) Retrospective measurement of childhood sexual abuse: a review of instruments. Child Maltreatment 9(2):201–217

Peters SD, Wyatt GE, Finkelhor D (1986) Prevalence. In: Finkelhor D, Araji S (eds) A sourcebook on child sexual abuse. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, pp 15–59

Stinson MH, Hendrick SS (1992) Reported childhood sexual abuse in university counseling center clients. J Couns Psychol 39(3):370–374

Read J, Hammersley P, Rudegeair T (2007) Why, when and how to ask about childhood abuse. Adv Psychiatr Treat 13:101–110

Muenzenmaier KH, Schneeberger AR, Seixas A, Castille D, Battaglia J, Link BG (2014) Stressful childhood experiences and clinical outcomes in people with serious mental illness: a gender comparison in a clinical psychiatric sample. J Family Violence (in press)

Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Hack T (2001) Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: the benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. Am J Public Health 91(6):940–946

Todahl JL, Linville D, Bustin A, Wheeler J, Gau J (2009) Sexual assault support services and community systems: understanding critical issues and needs in the LGBTQ community. Violence Against Women 15(8):952–976. doi:10.1177/1077801209335494

Freyd JJ, DePrince AP, Zurbriggen EL (2001) Self-reported memory for abuse depends upon victim-perpetrator relationship. J Trauma Dissociation 2(3):5–15

Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Hughes TL, Benson PW (2012) Characteristics of childhood sexual abuse in lesbians and heterosexual women. Child Abuse Negl 36(3):260–265. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.008

Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B (2011) Sexual revictimization and mental health: a comparison of lesbians, gay men, and heterosexual women. J Interpers Violence 26(9):1798–1814

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schneeberger, A.R., Dietl, M.F., Muenzenmaier, K.H. et al. Stressful childhood experiences and health outcomes in sexual minority populations: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49, 1427–1445 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0854-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0854-8