Abstract

Purpose

This study set out to investigate the patterns of referral in a sample (n = 206) of patients having first-time access to an Italian comprehensive program that targets the early detection of and early intervention on subjects at the onset of psychosis. The primary goal of the study was to investigate the duration of untreated illness (DUI) and/or the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in the sample since the implementation of the program.

Method

Data on pathways of referrals prospectively collected over a 11-year period, from 1999 to 2010; data referred to patients from a defined catchment area, and who met ICD-10 criteria for a first episode of a psychotic disorder (FEP) or were classified to be at ultra-high risk of psychosis (UHR) according to the criteria developed by the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation (PACE) Clinic in Melbourne. Changes over time in the DUI and DUP were investigated in the sample.

Results

Referrals increased over time, with 20 subjects enrolled per year in the latter years of the study. A large majority of patients contacted a public or private mental health care professional along their pathway to treatment, occurring more often in FEP than in UHR patients. FEP patients who had contact with a non-psychiatric health care professional had a longer DUP. Over time, DUP and DUI did not change in FEP patients, but DUI increased, on average, in UHR patients.

Conclusions

The establishment of an EIP in a large metropolitan area led to an increase of referrals from people and agencies that are not directly involved in the mental health care system; over time, there was an increase in the number of patients with longer DUI and DUP than those who normally apply for psychiatric services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The range of contacts made by distressed people and their relatives with individuals and organizations to seek help is known globally as the “pathway to care” [1]. The routes taken to gain access to help by patients experiencing symptoms of psychosis for the first time are influential in determining whether treatment is prompt or delayed [2]. Indeed, the concept of duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was developed to take into account the time that elapses from the onset of evident symptoms of psychosis (delusions, hallucinations, bizarre behavior) to the start of appropriate treatment, usually the prescription of antipsychotic drugs [3, 4]. There is evidence that delayed access to specialized services is specifically associated with poorer social functioning, a lower quality of life, a higher likelihood of complications such as substance abuse and law infringement, and a poorer response to therapy [5, 6]. Therefore, an investigation of the pathways to care is particularly relevant in patients who are experiencing prodromal symptoms or a first episode of psychosis. Different access points to the health care system may be associated with a prompt or delayed referral to psychiatric services [7], and this in turn may have consequences for both DUP and outcome.

Early intervention programs (EIPs) were organized all over the world in the form of pilot treatment centers to reduce the worst consequences of a delayed referral, and thus provide early detection and intensive focused treatment to people in the early phases of psychosis, whether in their first episode or at risk of it [8, 9]. Since a major goal of EIPs is to reduce the DUP, the investigation of the patterns of referral to psychiatric services is a necessary step to evaluate how this important goal in the treatment of psychosis is achieved. This information is useful both on clinical grounds and for service organizations, and may favor a better understanding of the factors involved in DUP length, as well as help to identify those pathways that may benefit the most from dedicated interventions.

The studies carried out so far indicate that there are two primary sources of delay in accessing EIPs: delay in help-seeking by both patients and carers, and delays within mental health services [10]. Stigma, and in particular fear of the label of a mental illness also contribute to raise the threshold for initiation of treatment [11, 12]. Different strategies were implemented to decrease DUP of patients referred to EIPs [13, 14]. The main adopted strategies were:

-

(a)

educational campaigns addressed to general practitioners and other health professionals to increase their ability of recognizing patients with psychosis and their willingness to refer them to specialized programs;

-

(b)

awareness campaigns addressed to the general public and health care professionals to increase understanding of psychosis and its treatment;

-

(c)

enrollment of patients at a higher risk of transition to psychosis, to intervene as soon as possible in case of psychotic break-down.

To date, the impact of EIPs on DUP has been mixed. One study from Canada found no differences in DUP length before and after the establishment of an EIP [15]. However, in the early treatment and identification of psychosis (TIPS) study, DUP was reduced after the establishment of the EIP [16]. The establishment of the EIP accompanied the start of awareness campaigns directed to the general public and health care professionals, which effectively reduced the DUP of patients at referral [17]; this reduction was no longer noted when the campaign was stopped [18]. In another study from Australia, a higher proportion of patients with longer DUP was observed in the group that was exposed to an awareness campaign on early intervention than in the control group [19]. Educational campaigns directed towards general practitioners were less effective. In the Lambeth Early Onset Crisis Assessment Team study, no differences were found in the DUP of patients given referrals by general practitioners randomized as part of an educational campaign, and by those who were not [20]. No effect of an educational campaign directed to general practitioners was reported in Birmingham either [21]. The mixed effects of EIP on DUP is largely influenced by the fact that these programs often identify cases with a very long DUP that may not have otherwise come into contact with the health care system were it not for the case detection strategies employed by the EIP.

Less is known about the impact of the establishment of an EIP on the heterogeneous group of those patients classified as having an ultra high-risk of developing a psychosis. This recently defined category includes people with signs of incipient psychosis, and principally involves three clusters of subjects: young people with attenuated positive symptoms, as revealed by dedicated interviews [22]; people with diagnosable transient psychotic symptoms, not stabilized in a syndrome yet [23, 24]; and a third category of people with genetic risk (first-degree relatives of subjects with psychosis), or meeting the criteria for schizotypal personality disorder, who are showing symptoms of deterioration [25]. These subjects are generally ill, and they can benefit greatly from psychiatric and/or psychological help [26]. The patients at a higher risk of transition to psychosis are one of the primary targets of EIPs, since the best chance of shortening the DUP is by intervening in the prodromal phases of the disorder [27, 28]. There is evidence that help-seeking attempts begin in the prodromal phase of the illness, well before full-blown psychosis starts [29–31].

This study set out to investigate the patterns of referral in a sample (n = 206) of patients accessing Programma2000 for the first time, a comprehensive program within the Department of Mental Health of the Niguarda Ca’ Granda Health Authority of Milan (Italy) that has been targeting the early detection of and early intervention on subjects at the onset of psychosis since 1999 [32, 33]. Patterns of referral were compared between the patients diagnosed with a first episode of psychosis (FEP) and the subjects classified as being at an ultra-high risk of psychosis (UHR) according to the criteria developed by the Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation (PACE) Clinic in Melbourne [24, 34]. The main goal of the study was to investigate the duration of untreated illness (DUI) and DUP of the referred patients over an 11-year period from the establishment of the EIP (available data are from January 1999 to December 2010).

Methods

Data were collected during the routine assessment of the patients participating in Programma2000 [32, 33]. The institutional review board approved the study, and all patients gave their informed consent. The sample included 206 patients from a catchment area in Milan catering to approximately 200,000 inhabitants. Milan is the main city of Lombardy, the largest and most affluent region in Italy.

Context of the study

In Lombardy, as in the rest of Italy, the mental health care system is based on a dedicated system of mental health departments [35, 36]. These departments are interconnected with general hospitals (where the operating psychiatric wards for acute treatment are located), and a network of community services covering all requirements of the child, adolescent and adult populations [37, 38]. This community mental health care network operates within the framework of a mixed private–public system of health care providers to ensure that patients are free to choose psychiatric care from among public and private centers [39, 40]. All psychiatric services are free of charge to patients and their families, since the costs of assessment and treatment are covered by general taxation, although some fees for psychotherapy are paid for directly by the patients. Patients who have been diagnosed with psychosis can still be exempt from paying for psychotherapy. The threshold for access to these services is very low, so patients can book a visit even without a formal request by their general practitioner.

All public psychiatric hospital services are open 24 h a day, with staff on duty at night; pharmacotherapy and individual supportive psychotherapy are the main treatment methods for patients with psychosis [38, 40]. Comorbidity for substance abuse is treated in collaboration with a dedicated team, which is external to the psychiatric service and works as part of the Drug Addiction Services [38]. School support, vocational rehabilitation and competency training are generally not offered to patients with psychosis as part of the standard care package, and in the health district covering the Lombardy Regional Authority, complex care packages are rarely provided as part of standard care [41]. For standard care, a specific protocol of care is not active for patients experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Patients are seen within 7–15 days from the request for an intervention, receive a clinical interview to ascertain diagnosis and comorbidity, and are prescribed pharmacotherapy and individual supportive psychotherapy [38, 42]. An investigation of the prescriptions offered to patients receiving standard care in Lombardy showed that about half of the patients diagnosed with schizophrenia do not receive the minimum adequate treatment, particularly those at their first episode [43].

Programma2000 was established in order to offer a dedicated, evidence-based and expertise-driven protocol of care to patients experiencing the first-episode psychosis or in the prodromal phase of a psychosis.

Assessment and diagnosis

All patients who were referred to Programma2000 underwent a comprehensive, multidimensional evaluation. In this study, the following standardized assessment instruments were considered: (i) a socio-demographic form; (ii) the early recognition inventory retrospective assessment of symptoms checklist (ERIraos-CL), a 17-item screening checklist intended to select the persons needing a more in-depth assessment [44, 45]; (iii) the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS), to assess psychopathology and disability, which includes 12 five-point items to evaluate clinical and social functioning over the preceding 2 weeks [46]; (iv) the 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), to assess general psychopathology [47, 48]; and (v) the global assessment of functioning (GAF) [49].

The main criterion for inclusion on the basis of a first episode of psychosis was a diagnosis of schizophrenia or related syndromes (F20–29 in ICD-10) according to the ICD-10 [50]. To be enrolled in the Programma2000, patients with a first episode of psychosis had to have a DUP less than 24 months. Within the early intervention paradigm, a DUP less than 24 months is considered the limit to start an early intervention protocol of care [51]. Of course, patients with longer DUP are still worthy of treatment, but they need different protocols of care to take into account the impact of the consequences of a long period of untreated psychosis [52, 53].

Referred patients considered to be at an ultra-high risk of psychosis were screened when they presented one of these operational criteria for UHR, as developed and defined by the PACE Clinic in Melbourne: (1) attenuated psychotic symptoms syndrome, characterized by subthreshold positive psychotic symptoms during the last year; or (2) brief, limited, and intermittent psychotic syndrome, including people who experienced episodes of frank psychotic symptoms that have lasted no longer than a week and spontaneously abated; or (3) familial genetic risk, including people with a first-degree relative diagnosed with a psychotic disorder or showing criteria for the schizotypal personality disorder in addition to evidence of deterioration in functioning in the last year [24, 34]. Patients were initially screened on the ERIraos-CL; to be enrolled in treatment as UHR, patients must have a score ≥12 on the ERIraos-CL, and present evidence of positive symptoms on the BPRS—even if in an attenuated or sub-threshold form. The threshold score ≥12 on the ERIraos-CL better defined the patients at risk of transition in the German schizophrenia network study [54].

In both FEP and UHR patients, affective psychosis (bipolar disorder, or unipolar disorder with psychotic features) was an exclusion criterion, as was a comorbid persistent substance-use dependent disorder, while substance use/abuse without dependence was not. A past or present diagnosis of psychosis in the spectrum of schizophrenia was a mandatory exclusion criterion for UHR diagnosis.

DUI and DUP were based on interviews with the patient and of at least one key informant (a close relative, preferably a parent); they were both measured from the onset of key symptoms (anxiety, depression or social withdrawal for DUI; hallucinations, delusions or bizarre behavior for DUP) to the start of treatment prescribed by a psychiatrist (pharmacotherapy for DUP and DUI in FEP patients, or psychotherapy for DUI in UHR patients). DUP was measured in days, DUI in months. To measure DUP/DUI, we considered the symptoms as they were elicited by the ERIraos-CL, by considering the patient’s estimated time of onset of key symptoms as listed in the tool. Further information on time of onset of key symptoms was obtained by direct interview of a key informant. The DUI/DUP assessment was made jointly by a therapist (usually a psychiatrist) and a researcher (usually a psychologist or an educator) of the team, and in problematic cases consensus with a senior clinician was sought.

A history of suicide attempt and of illicit substance abuse was also considered as an indicator of illness severity; because these events/conditions are likely to raise concern in the family, they may also induce contact-seeking with psychiatric services [55].

Patterns of referral

From its conception, Programma2000 focused on the education and training of health care professionals working within the public health care network and, in particular, mental health clinicians and clinic and agency staff serving adolescents and young adults. The aim was to raise awareness on the importance of early detection and referral of patients with or at risk of psychosis, and to disseminate knowledge of the multi-dimensional protocol of care applied by Programma2000 [32, 33]. Over time, more attention was paid to schools and the public in general through awareness campaigns that were organized primarily by a single dedicated organization: TULIP, Tutti Uniti Lavoriamo Per Intervenire Precocemente (working all together for early intervention; www.iniziativatulip.org).

At present, sources of referral for Programma2000 are mental health care professionals and consulting rooms, family physicians, or direct family referrals in response to awareness campaigns; self-referral is allowed as well. Police and emergency services, social services and education referrals were less often involved as sources of referral for Programma2000. More often, these referrals pass through mental health care professionals and consulting rooms. Information on referrals was recorded following an ad-hoc schedule, from the direct interview of the patients and at least one key informant (in this young population, generally a parent), and included:

-

First contact: this is the contact along the care pathway from whom help was first sought after the onset of psychosis, and may include: a psychiatrist from a public or private institute, the patient’s general practitioner, a psychologist, a neurologist, a general hospital physician, a healer, a counselor, or another professional category not listed above;

-

Care pathway contact: this is the agency or service that the patient came into contact with on his/her path to Programma2000; it may include the community mental health care center, the drug dependence department, a university psychiatric clinic, a private psychiatric facility, a medical division, a surgery division, a crisis center, a residential facility, the counseling service of the school, the office of the general practitioner, or another category of agencies or services not listed above;

-

Additional agencies involved in the referral: any other agencies involved in the patient’s contacting Programma2000, and may include: the Police, legal authorities, the ambulance service, a hospital’s emergency room;

-

Family involvement: this information explains whether the family requested the intervention and/or accompanied the patient to the center.

Compulsory admissions were recorded specifically as such.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) for Windows (Chicago, Illinois 60606, USA), version 13. All tests were two-tailed, threshold of significance was set at p = 0.05. Categorical data were analyzed in inter-group comparisons with χ 2, with Yates’ correction when appropriate, or the Fisher exact test (when n < 5 in any cell). The Student’s t test was used to analyze continuous variables (age); the Mann–Whitney (M–W) U test was used to compare the ordinal variables. Pearson’s r or the Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients were used to examine associations between two variables. The effect sizes of the differences on the ordinal variables between FEP and UHR patients were calculated according to Cliff’s delta with confidence of interval (CI), which is appropriate in case of violations of normality. Cliff’s delta represents the degree of overlap between two score distributions [56]. It ranges from −1 to +1 (according to the order of overlap between the two groups), and is reported as the expected value of zero if the two sample distributions are extracted from the same population.

Results

A total of 462 subjects have been referred to the service since its establishment (available data are from January 1999 to December 2010). Among these, 24 did not complete the assessment.

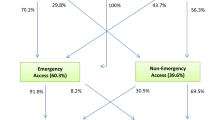

Among those who completed the assessment (n = 438), 200 were recommended to the service that had originally asked for the evaluation, either because they were living in other regions of Italy (n = 49), or they had a DUP longer than 24 months (n = 52), or they did not meet the a priori criteria for identifying a UHR case (n = 99).

238 subjects were offered a dedicated protocol of care: 206 accepted and were enrolled in the program, 17 refused and 15 did not show up after accepting the proposal (see Fig. 1 for details). The rejected cases and those who refused treatment received appropriate advice for future treatment.

Both FEP and UHR samples included a preponderance of male patients, with a slight excess of male patients in the FEP group; 67 and 60 % of the patients, respectively, had a family history of psychopathology, principally first/second-degree relatives diagnosed with psychosis or an affective disorder (Table 1).

FEP and UHR patients did not differ in terms of age, educational level or married status, and family history of psychopathology. As expected on the basis of classification, FEP patients were more severe than UHR patients, and scored higher on the ERIraos (Cliff’s delta = 0.49; 95 % CI = 0.34–0.62), the HoNOS (Cliff’s delta = 0.17; 95 % CI = 0.01–0.33), and the BPRS (Cliff’s delta = 0.23; 95 % CI = 0.06–0.39), and lower on the GAF (Cliff’s delta = −0.46; 95 % CI = −0.59 to −0.30).

Patterns of referral

Referrals increased over time, with 20 subjects enrolled per year in the latter years of the study. The large majority of patients contacted a public or private mental health care center in their pathways to treatment, which occurred more often in FEP than in UHR patients (Table 2).

Police, legal authorities or emergency agencies were rarely involved in the referral to Programma2000. Conversely, families asked for the intervention and accompanied the patient in about half of the cases, more often in FEP than in UHR patients.

Overall, 14 FEP patients and 1 UHR patient were compulsorily admitted to hospital in the period immediately preceding the referral to Programma2000.

Over time (from 1999 to 2010), referrals through sources other than a mental health care professional increased, and this change was statistically significant in UHR patients (year versus number of referrals by someone who is not a mental health care professional: Spearman’s rho = 0.23, p = 0.02), but not in FEP patients (Spearman’s rho = 0.09, p = 0.33).

Over time DUP and DUI did not change in FEP patients, but DUI increased, on average, in UHR patients (year versus DUI: Spearman’s rho = 0.23, p = 0.03), changing from 23.5 months (SD = 20.9) in 2002–2003 (patients: n = 23) to 38.2 months (SD = 21.2) in 2009–2010 (n = 14).

Correlates of referral

The FEP patients who joined Programma2000 through a mental health care professional were marginally more severe than those who contacted it via other referral sources or by self-referral, but had a shorter DUI and DUP (Table 3).

UHR patients showed no differences by pattern of referral as far as severity of psychopathology or DUI were concerned (Table 3, bottom).

Family involvement was not related to DUP or DUI in either sample, nor was family history of psychopathology related to a lower chance of contacting a mental health care professional in the pattern of referral to Programma2000 (data available upon request). However, in the whole sample (n = 206) family involvement was related to social and occupational functioning as measured by the GAF: the lower the GAF, i.e. the poorer the functioning of the patient, the more likely that the referral was requested by a family member (Spearman’s rho = −0.201, p = 0.006) and that the family accompanied the patient to the center (Spearman’s rho = −0.247, p = 0.001).

In both samples, all cases with a history of attempted suicide before enrollment were referred by a mental health care professional, while there was no difference in type of referral amongst the cases with a history of illicit substance use.

Discussion

FEP patients were more likely than UHR patients to contact an early intervention program through the referral of a mental health care professional. In all likelihood, this reflects greater severity of FEP patients compared to UHR patients. Indeed, in the FEP sample, the patients who joined Programma2000 via sources of referral other than a mental health care professional were marginally less severe than those who were referred to Programma2000 by a psychiatrist. Conversely, it is likely that the cases with higher severity prompted the patients and their families to access the health care system via a specialized psychiatric contact. Indeed, all cases with a history of attempted suicide before enrollment had been referred to Programma2000 by a mental health care professional.

Main differences between FEP and UHR patients in pattern of referrals

FEP and UHR patients did not differ as far as main socio-demographic characteristics were concerned, but a greater proportion of females among UHR patients. FEP patients were more severe than UHR patients, and this resulted in FEP patients being more often referred to the Programma2000 by a mental health care professional and more often compulsorily admitted to hospital. Greater severity of patients, and probably a greater burden of care, prompted relatives of FEP patients to require psychiatric assessment more often than relatives of the UHR patients. No other differences emerged between FEP and UHR samples, probably as a reflection of the similarity of the conditions as far as the impact of symptoms on family climate is concerned [57].

Role of patients’ families in accessing Programma2000

Past studies showed that family members were the key in initiating contact for both FEP and UHR patients [31, 58–60]. Patients’ families were often involved in accessing Programma2000, too. As in past studies [31], the family had a role in guiding the patient with an ongoing first episode of psychosis towards treatment. Indeed, families play a critical role in supporting patients with psychosis, both because relatives are able to detect the indicators of symptomatic malfunctioning [61], and because they can offer guidance, support and supervision to access and maintain compliance with treatment [60, 62]. Lower family support was associated with longer DUP in both western and non-western countries [63, 64]. Conversely, support from the family or the partner results in a shorter delay in seeking help for mental problems [65], with the possible exception of the families with a past history of psychiatric hospitalization of a family member, which were found less likely to recommend other family members to mental health services [31, 66]. However, in this study a family history of psychopathology did not influence the pattern of referral to Programma2000. Overall, family support implies a heavier family burden in the care of patients with psychosis [40, 67]. Better support, education and information are expected to alleviate this family burden [68], and Programma2000 activated a dedicated protocol of psychoeducation and support aimed at reducing expressed emotion and other sources of family stress with an impact on the patient’s clinical status [57].

Role of emergency services and police in referrals to Programma2000

While the family was frequently involved in the referral of the patient to Programma2000, the involvement of the police or emergency services was rare. Emergency agencies, the police or legal authorities are the ones typically involved in compulsory admission to hospital psychiatric services. The direct involvement of the police and/or emergency services in the access to psychiatric services was linked to poor subsequent engagement in the process of care, as well as to dissatisfaction with services [69–71]. Programma2000 operates within an outpatient setting and is not likely to be directly involved in referrals that might imply compulsory hospitalization. Nevertheless, a subset of patients who were referred to Programma2000 were compulsorily admitted to hospital before their first contact with the EIP service; they were, however, referred to Programma2000 by psychiatrists operating within the psychiatric hospital division rather than by the police or legal authorities. Since the EIP service is not directly related to compulsory admission, this might reduce negative effects of compulsory admission on engagement in the process of care and dissatisfaction with services.

Lagged effect on referrals made by people who were not mental health care professionals

Over time, referrals to Programma2000 through sources other than mental health care professionals increased, at the expense of a concurrent increase of DUP in FEP patients and DUI in UHR patients. Delays in referrals to a specialized EIP from referral sources other than a mental health care professional can be attributed, in part, to the lower severity of the case, at least in FEP patients. Indeed, mild levels of distress could lead to less active help-seeking behaviors [59]. Similar to the present study, a study from Canada associated longer DUP at time of referral with the first help-seeking contact made by a non-medical professional [72]. A lagged effect on referrals by people who were not mental health care professionals was observed in UHR samples, too [73]. However, in Switzerland, patients with suspected at-risk states for psychosis contacted more frequently a professional who was not a mental health care professional, generally a general practitioner, when they had insidious and more unspecific features [74]. In past studies, an insidious onset of psychosis was associated with longer DUI and DUP [63, 75]. Sometimes non-specific symptoms of irritability, anxiety, depression or social withdrawal may prompt the patient to seek help during the prodromal phase of the disorder. Some study found longer delay for patients who were treated already by a mental health care service [76], probably as a reflection of the masking of symptoms by pharmacotherapy. Therefore, a different onset course of the disorder—acute versus insidious—and the masking effects of pharmacotherapy prescribed to treat symptoms in the prodromal phase might determine differences in the modality of referral to an EIP and have an impact on DUP or DUI as well.

Impact of the establishment of an EIP on the DUI and DUP of referred patients

The main finding of this study is that the establishment of an EIP in a large metropolitan area such as Milan led to an increase of referrals from people and agencies that are not directly involved in the mental health care system, also attracting patients with longer DUI and DUP than those who habitually access psychiatric services. We can advance that this subgroup of patients would have further delayed contacting a psychiatric service because of diffidence towards psychiatric treatment, fear of stigma and other reasons causing poor involvement with psychiatric services. We might have missed some patients with very long DUP since criteria of enrollment in the EIP fixed a DUP less than 24 months as the limit to start an early intervention protocol of care. This criterion might limit comparability with EIPs that do not preclude access to the program for those with very high DUP.

The effect produced through the establishment of an EIP on DUI/DUP had been observed before. For example, in Canada after the establishment of an early case identification program, which was designed to promote early recognition and referral of individuals with FEP from any possible source of referral, the patients who contacted an EIP had longer prodromal periods and a higher level of psychotic and disorganization symptoms than before [15].

The results of this study cannot be easily compared with the studies from other countries, since the organization and accessibility of the public mental health care system play a role in the pathways of referral to a specialized EIP. In England, the Lambeth Early Onset Crisis Assessment Team found higher detection and referral rates of first-episode psychosis patients after an education program addressing general practitioners [20]. On the contrary, in countries with a large number of mental health care professionals in private practice or with different psychosocial contact facilities, as in Germany [77] or Italy [78], general practitioners are less important pathways of referral for patients with first-episode psychosis. Therefore, in these countries the campaigns aimed at reducing delay in treatment should focus on health care services rather than on general practitioners [77]. In the countries where treatment costs heavily burden patients and their families, as in the United States, patients without health insurance and/or with financial problems meet huge barriers when seeking help, and consequently have longer DUP [79]. In these countries, interventions aimed at minimizing economic and financial barriers to treatment can improve FEP patients’ access to care, but this is not the case with Italy, where the costs of mental disorder treatment are fully borne by the national health care system.

Limits and strengths of the study

Sample size prevented the execution of multivariate analyses and, in all likelihood, limited the chance of finding associations for some occurrences. For example, the links between family involvement in the referral process and social and occupational functioning of the patient were seen in the whole sample only, most likely because both diagnostic subgroups (FEP and UHR) were too small to reliably detect these links.

We studied the referrals to an EIP but did not have information on the pathways that preceded access to the service. While this was not an aim of the study, the pathways that led patients to a mental health care professional might provide some insight into the reasons that accelerate the access to care. In this study, patients with psychosis who addressed the service via the referral of a mental health care professional had lower DUP than those who did not contact a mental health care professional in their pathways to care. Some intermediate contact may be more effective in detecting problems that require psychiatric assessment.

We had no control data, either for a site that does not have an established EIP or historical data prior to the establishment of the EIP, so we cannot exclude that the changes we observed over time in the pattern of referrals to the Programma2000 were the result of changes in public attitudes or greater awareness of mental healh issues unrelated to the establishment of the EIP.

The major advantage of this study is the provision of information on the referral to an EIP with data on both FEP and UHR patients. The UHR category involves a heterogeneous group of help-seeking patients who may benefit from specialized treatment [26]. Improvement in the detection of those at higher risk of transition to psychosis is a mandatory step in the effort to reduce the long-term impact of psychosis. To this aim, education and training of health care professionals is likely to promote the early recognition of the prodromals of psychosis, while education and training of school counselors, and general public awareness campaigns aimed at reducing stigma and fear of receiving treatment for psychological distress, might be effective in reducing delay in referral for those in need [11, 80]. Awareness campaigns on psychosis were found effective in decreasing DUP after the opening of an EIP. A study carried out in Singapore found a shortening of DUP in the referral to an EIP after the start of a public awareness-raising campaign and networking with primary health care providers; an increase in the proportion of self and family referrals was found as well [17]. The TIPS study also found that public awareness campaigns had a major impact on the DUP of patients with psychosis, but when the awareness campaign was stopped, DUP increased again and fewer patients directly contacted the easy-access detection teams [18]. This suggests the need for ongoing, continuous interventions aimed at informing health care and school professionals, and families on the characteristics of psychosis and its treatment [18, 81].

References

Rogler LH, Cortes DE (1993) Help-seeking pathways: a unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry 150:554–561

Singh SP, Grange T (2006) Measuring pathways to care in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophr Res 81:75–82

Crow TJ, MacMillan JF, Johnson AL, Johnstone EC (1986) A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic neuroleptic treatment. Br J Psychiatry 148:120–127

McGlashan T (1999) Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: marker or determinant of course? Biol Psychiatry 46:899–907

Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T (2005) Association between duration of untreated psychosis and in cohorts of first-episode outcome patients—a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:975–983

Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA (2005) Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 162:1785–1804

Anderson KK, Fuhrer R, Malla AK (2010) The pathways to mental health care of first-episode psychosis patients: a systematic review. Psychol Med 40:1585–1597

McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO (1996) Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: rationale. Schizophr Bull 22:201–222

McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger GP, Bechdolf A, Francey SM, Berger G, Riecher-Rössler A, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Nordentoft M, Hickie I, McGuire P, Berk M, Chen EY, Keshavan MS, Yung AR (2009) Intervention in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J Clin Psychiatry 70:1206–1212

Birchwood M, Lester H, McCarthy L, Jones P, Fowler D, Amos T, Freemantle N, Sharma V, Lavis A, Singh S, Marshall M (2013) The UK national evaluation of the development and impact of Early Intervention Services (the National EDEN studies): study rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Early Interv Psychiatry. doi:10.1111/eip.12007

Franz L, Carter T, Leiner AS, Bergner E, Thompson NJ, Compton MT (2010) Stigma and treatment delay in first-episode psychosis: a grounded theory study. Early Interv Psychiatry 4:47–56

Serra M, Lai A, Buizza C, Pioli R, Preti A, Masala C, Petretto DR (2013) Beliefs and attitudes among Italian high school students toward people with severe mental disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 201:311–318

Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, Pilling S, Hobbs L, Hinton M, Johnson S (2011) Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 198:256–263

Connor C, Birchwood M, Palmer C, Channa S, Freemantle N, Lester H, Patterson P, Singh S (2013) Don’t turn your back on the symptoms of psychosis: a proof-of-principle, quasi-experimental public health trial to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis in Birmingham, UK. BMC Psychiatry 13(1):67. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-67

Malla A, Norman R, Scholten D, Manchanda R, McLean T (2005) A community intervention for early identification of first episode psychosis: impact on duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and patient characteristics. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:337–344

Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Joa I, Melle I, Friis S, Opjordsmoen S, Rund BR, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan TH (2005) Pathways to care for first-episode psychosis in an early detection health care sector: part of the Scandinavian TIPS study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 48:s24–s28

Chong SA, Mythily S, Verma S (2005) Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis and changing help-seeking behaviour in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:619–621

Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, Friis S, McGlashan T, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, Larsen TK (2008) The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: information campaigns. Schizophr Bull 34:466–472

Krstev H, Carbone S, Harrigan SM, Curry C, Elkins K, McGorry PD (2004) Early intervention in first-episode psychosis—the impact of a community development campaign. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:711–719

Power P, Iacoponi E, Reynolds N, Fisher H, Russell M, Garety P, McGuire PK, Craig T (2007) The Lambeth Early Onset Crisis Assessment Team study: general practitioner education and access to an early detection team in first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 51:s13313–s13319

Lester H, Birchwood M, Freemantle N, Michail M, Tait L (2009) REDIRECT: cluster randomised controlled trial of GP training in first-episode psychosis. Br J Gen Pract 59:e183–e190

Olsen KA, Rosenbaum B (2006) Prospective investigations of the prodromal state of schizophrenia: review of studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 113:247–272

Simon AE, Dvorsky DN, Boesch J, Roth B, Isler E, Schueler P, Petralli C, Umbricht D (2006) Defining subjects at risk for psychosis: a comparison of two approaches. Schizophr Res 81:83–90

Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP, Ward J, Donovan K, Kelly D, Francey SM, Yung AR (2007) Medium term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res 96:25–33

Cornblatt B, Lencz T, Smith CW, Correll CU, Auther A, Nakayama E (2003) The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr Bull 29:633–651

Preti A, Cella M (2010) Randomized controlled trials in people at ultra high risk of psychosis: a review of treatment effectiveness. Schizophr Res 123:30–36

McGorry PD (2007) Issues for DSM-V: clinical staging: a heuristic pathway to valid nosology and safer, more eff ective treatment in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 164:859–860

Raballo A, Larøi F (2009) Clinical staging: a new scenario for the treatment of psychosis. Lancet 374:365–367

Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Hutchinson J, Addington D (2002) Pathways to care: help seeking behaviour in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 106:358–364

Murphy J, Shevlin M, Houston J, Adamson G (2012) A population based analysis of subclinical psychosis and help-seeking behavior. Schizophr Bull 38:360–367

O’Callaghan E, Turner N, Renwick L, Jackson D, Sutton M, Foley SD, McWilliams S, Behan C, Fetherstone A, Kinsella A (2010) First episode psychosis and the trail to secondary care: help-seeking and health-system delays. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45:381–391

Cocchi A, Meneghelli A, Preti A (2008) “Programma 2000”: celebrating 10 years of activity of an Italian pilot program on early intervention in psychosis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 42:1003–1012

Meneghelli A, Cocchi A, Preti A (2010) “Programma2000”: a multi-modal pilot program on early intervention in psychosis underway in Italy since 1999. Early Interv Psychiatry 4:97–103

Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A (1996) Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis. Schizophr Bull 22:283–303

de Girolamo G, Cozza M (2000) The Italian psychiatric reform: a 20-year perspective. Int J Law Psychiatry 23:197–214

Lora A, Barbato A, Cerati G, Erlicher A, Percudani M (2011) The mental health care system in Lombardy, Italy: access to services and pattern of care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:447–454

de Girolamo G, Barbato A, Bracco R, Gaddini A, Miglio R, Morosini P, Norcio B, Picardi A, Rossi E, Rucci P, Santone G, Dell’Acqua G (2007) The characteristics and activities of acute psychiatric inpatient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Br J Psychiatry 191:170–177

Gigantesco A, Miglio R, Santone G, de Girolamo G, Bracco R, Morosini P, Norcio B, Picardi A, PROGRES group (2007) The process of care in general hospital psychiatric units: a national survey in Italy. Austr N Z J Psychiatry 41:509–518

Fattore G, Percudani M, Pugnoli C, Contini A, Beecham J (2000) Mental health care in Italy: organisational structure, routine clinical activity and costs of a Community Psychiatric Service in Lombardy Region. Int J Soc Psychiatry 46:250–265

Preti A, Rucci P, Santone G, Picardi A, Miglio R, Bracco R, Norcio B, de Girolamo G, PROGES-Acute group (2009) Patterns of admission to acute psychiatric inpatient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Psychol Med 39:485–496

Lora A, Cosentino U, Gandini A, Zocchetti C (2007) Which community care for patients with schizophrenic disorders? Packages of care provided by Departments of Mental Health in Lombardy (Italy). Epidemiol Psichiatria 16:330–338

Preti A, Rucci P, Gigantesco A, Santone G, Picardi A, Miglio R, de Girolamo G, PROGRES-Acute group (2009) Pattern of care in patients discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44:767–776

Lora A, Conti V, Leoni O, Rivolta AL (2011) Adequacy of treatment for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective disorders in Lombardy, Italy. Psychiatr Serv 62:1079–1084

Häfner H, Riecher–Rossler A, Hambrecht M (1992) IRAOS: an instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 6:209–223

Maurer K, Hörrmann F, Trendler G, Schmidt M, Häfner H (2006) Früherkennung des Psychoserisikos mit dem Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos) Beschreibung des Verfahrens und erste Ergebnisse zur Reliabilität und Validität der Checkliste [Identification of psychosis risk by the Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos)—description of the schedules and preliminary results on reliability and validity of the checklist] [German]. Nervenheilkunde 25:11–16

Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, Park SB, Hadden S, Burns A (1998) Health of the nation outcome scales (HoNOS): research and development. Br J Psychiatry 172:11–18

Overall JE, Gorham DE (1962) The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep 10:799–812

Roncone R, Ventura J, Impallomeni M, Falloon IR, Morosini PL, Chiaravalle E, Casacchia M (1999) Reliability of an Italian standardized and expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 4.0) in raters with high vs. low clinical experience. Acta Psychiat Scand 100:229–236

Moos RH, McCoy L, Moos BS (2000) Global assessment of functioning (GAF) ratings: determinants and roles as predictors of 1-year treatment outcomes. J Clin Psychology 56:449–461

WHO (World Health Organization) (1992) Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). WHO Press, Geneve

Birchwood M (2000) Early intervention and sustaining the management of vulnerability. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 34(Suppl):S181–S184

Larsen TK, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S (1998) First-episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated psychosis. Pathways to care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 172:45–52

Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, van der Heiden W, Hambrecht M, Schultze-Lutter F (2003) Modeling the early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 29:325–340

Maurer K, Hörrmann FH, Häfner H (2006) Evaluation of psychosis rsk by the schedule ERIraos. Results based on 1 year transition rates in the German schizophrenia network study. Schizophr Res 86:S19

Øiesvold T, Bakkejord T, Hansen V, Nivison M, Sørgaard KW (2012) Suicidality related to first-time admissions to psychiatric hospital. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:419–425

Cliff N (1993) Dominance statistics: ordinal Analyses to answer ordinal questions. Psychol Bull 114:494–509

Meneghelli A, Alpi A, Pafumi N, Patelli G, Preti A, Cocchi A (2011) Expressed emotion in first-episode schizophrenia and in ultra high-risk patients. Results from Programma 2000 (Milan, Italy). Psychiatry Res 189:331–338

Shin YM, Jung HY, Kim SW, Lee SH, Shin SE, Park JI, An SK, Kim YH, Chung YC (2010) A descriptive study of pathways to care of high risk for psychosis adolescents in Korea. Early Interv Psychiatry 4:119–123

Chung YC, Jung HY, Kim SW, Lee SH, Shin SE, Shin YM, Park JI, An SK, Kim YH (2010) What factors are related to delayed treatment in individuals at high risk for psychosis? Early Interv Psychiatry 4:124–131

Fridgen GJ, Aston J, Gschwandtner U, Pflueger M, Zimmermann R, Studerus E, Stieglitz RD, Riecher-Rössler A (2012) Help-seeking and pathways to care in the early stages of psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi:10.1007/s00127-012-0628-0

Norman RM, Malla AK, Manchanda R (2007) Delay in treatment for psychosis : its relation to family history. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:507–512

Rabinovitch M, Béchard-Evans L, Schmitz N, Joober R, Malla A (2009) Early predictors of nonadherence to antipsychotic therapy in first-episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry 54:28–35

Thomas SP, Nandhra HS (2009) Early intervention in psychosis: a retrospective analysis of clinical and social factors influencing duration of untreated psychosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 11:212–214

Oliveira AM, Menezes PR, Busatto GF, McGuire PK, Murray RM, Scazufca M (2010) Family context and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP): results from the Sao Paulo study. Schizophr Res 119:124–130

Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, Lubell KM (1998) How people get into mental health care services: storis of choice, coercion and ‘muddling through’ from ‘first-timers’. Soc Sci Med 46:275–286

Verdoux H, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalan F, Gonzales B, Pauillac P, Fournet O, Liraud F, Beaussier J, Gaussares C, Etchegaray B, Bourgeois M, van Os J (1998) Prediction of duration of psychosis before first admission. Eur Psychiatry 13:346–352

Magliano L, Fiorillo A, De Rosa C, Malangone C, Maj M, The National Mental Health Project Working Group (2005) Family burden in long-term diseases: a comparative study in schizophrenia vs. physical disorders. Soc Sci Med 61:313–322

Gerson R, Davidson L, Booty A, McGlashan T, Malespina D, Pincus HA, Corcoran C (2009) Families’ experience with seeking treatment for recent-onset psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 60:812–816

Bhugra D, Harding C, Lippett R (2004) Pathways into care and satisfaction with primary care for black patients in South London. J Ment Health 13:171–183

Compton MT (2005) Barriers to initial outpatient treatment engagement following first hospitalization for a first episode of nonaffective psychosis: a descriptive case series. J Psychiatr Pract 11:62–69

Levine SZ (2008) Population-based examination of the relationship between type of first admission for schizophrenia and outcomes. Psychiatr Serv 59:1470–1473

Bechard-Evans L, Schmitz N, Abadi S, Joober R, King S, Malla A (2007) Determinants of help-seeking and system related components of delay in the treatment of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 96:206–214

McFarlane WR, Cook WL, Downing D, Verdi MB, Woodberry KA, Ruff A (2010) Portland identification and early referral: a community-based system for identifying and treating youths at high risk of psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 61:512–515

Platz C, Umbricht DS, Cattapan-Ludewig K, Dvorsky D, Arbach D, Brenner HD, Simon AE (2006) Help-seeking pathways in early psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41:967–974

Iyer SN, Boekestyn L, Cassidy CM, King S, Joober R, Malla AK (2008) Signs and symptoms in the pre-psychotic phase: description and implications for diagnostic trajectories. Psychol Med 38:1147–1156

Boonstra N, Sterk B, Wunderink L, Sytema S, De Haan L, Wiersma D (2012) Association of treatment delay, migration and urbanicity in psychosis. Eur Psychiatry 27:500–505

Fuchs J, Steinert T (2004) Patients with a first episode of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis and their pathways to psychiatric hospital care in South Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:375–380

de Girolamo G, Bassi M, Neri G, Ruggeri M, Santone G, Picardi A (2007) The current state of mental health care in Italy: problems, perspectives, and lessons to learn. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257:83–91

Compton MT, Ramsay CE, Shim RS, Goulding SM, Gordon TL, Weiss PS, Druss BG (2009) Health services determinants of the duration of untreated psychosis among African-American first-episode patients. Psychiatr Serv 60:1489–1494

Yap MB, Wright A, Jorm AF (2011) The influence of stigma on young people’s help-seeking intentions and beliefs about the helpfulness of various sources of help. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:1257–1265

Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, Friis S, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan T, Larsen TK (2007) Effects on referral patterns of reducing intensive informational campaigns about first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 1:340–345

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the members of Programma2000 who contributed to the collection of data. Programma2000 is entirely financed by a grant from the Lombardy Regional Health Authority (Italy). The Lombardy Regional Health Authority had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Dr Maria T. Cascio was the recipient of a Grant of the Regione Sardegna (Grant no. T2-MAB-A2008-138). The Regione Sardegna had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. No other forms of financial support were received for this study.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cocchi, A., Meneghelli, A., Erlicher, A. et al. Patterns of referral in first-episode schizophrenia and ultra high-risk individuals: results from an early intervention program in Italy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 1905–1916 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0736-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0736-5