Abstract

Background

Recent evidence that treatment delay may compromise the potential for recovery from psychotic disorders has resulted in increased interest in factors that influence help seeking. In this paper, we test the hypotheses, derived from past research, that having a positive family history of a psychotic disorder in first or second degree relatives will be associated with a shorter duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), but a longer duration of untreated illness (DUI). Data were derived from 169 patients who presented for treatment to a first episode psychotic disorders program. Information was collected concerning family history, DUP, DUI and the timing of family recognition of the need for help.

Results

The findings failed to confirm a positive family history being associated with shorter DUP, but did support the prediction of such a history being related to longer DUI. Paradoxically, given the latter findings, families with a history of psychotic illness were more likely to recognize the need for help for the ill person prior to the onset of psychotic symptoms. The difference in DUI appears to reflect the presence of a longer period of early signs prior to the emergence of psychosis in those cases with a positive family history.

Conclusions

These findings suggest the importance of examining family history as a possible confound of any relationship between DUI and long-term course of illness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introdution

With recent evidence of the possible implications of duration of treatment delay for recovery from schizophrenia and related disorders [21–23, 25, 26, 31], there has been increasing interest in pathways to care for those with these illnesses [5, 7, 19, 27, 28]. Treatment delay can be defined in terms of time between onset of clear symptoms of psychosis and the beginning of effective treatment (commonly referred to as duration of untreated psychosis or DUP) or the delay to treatment from onset of any psychiatric symptoms (duration of untreated illness or DUI). These two indices of treatment delay can differ substantially because there are often non-specific signs or symptoms such as anxiety, irritability and anger, depressed mood, social withdrawal, poor concentration, reduced functioning, etc., which precede the onset of frank psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions [3, 8, 29]. Up to 40% of first episode patients with psychotic disorders seek help for such early signs from mental health services prior to the onset of psychosis [1, 17, 28].

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders typically have an early age of onset and those afflicted often do not recognize the need for treatment [2, 6]. Family members, usually parents, therefore, often play a crucial role in help seeking [6, 12, 15]. Hambrecht [10] proposed two equally plausible, but opposing postulates concerning the possible effect of family history of psychosis on help seeking. One is that a family experience of such a disorder could lead to more rapid response because of relatives’ increased sensitivity to signs of illness and recognition of the need for treatment. The other hypothesis is that experience of the negative sequelae and burden associated with psychotic illness such as schizophrenia could result in denial, thereby increasing treatment delay. Based on extent of agreement between family members and patients in recollection of early symptoms, Hambrecht concluded that families with a history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders were more perceptive with respect to positive symptoms of schizophrenia (hallucinations and delusions) than those without a family history, but the opposite appeared to be the case with respect to less specific signs such as changes in affect and behaviour and the presence of negative symptoms.

The evidence that treatment seeking can occur in response to either specific symptoms of psychosis or non-specific signs when considered in juxtaposition with the findings of Hambrecht et al. [10] suggest that the relationship between a family history of psychotic disorders and help seeking may well be complex. Hambrecht’s conclusion that family members are less sensitive to non-specific signs leads to the hypothesis that the delay between onset of signs and symptoms not-specific to psychosis and the first contact with professional help providers (DUI) would be greater for those with a positive family history. On the other hand Hambrecht’s conclusion that family members with experience of psychotic illness may be more sensitive to positive symptoms of psychosis such as hallucinations and delusions suggests the hypothesis that DUP would be shorter for individuals with a positive family history. We are unaware of any data that have been presented relevant to the first hypothesis. Consistent with the second hypothesis Chen et al. [4] have recently reported a positive family history of psychosis to be associated with shorter DUP, but others have failed to find such a relation [6, 35], so there is a particular need to replicate Chen et al.’s findings and examine their relation to family recognition.

In this paper, we use data from the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychosis (PEPP) in London, Canada to test the above hypotheses. Furthermore, we will examine the extent to which delay in family members’ recognition of need appear to mediate any differences in treatment delay.

Methods

Subjects

The data in this paper are from patients who were admitted to the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychoses (PEPP) in London Ontario Canada, between February 1998 and July 2004. PEPP provides comprehensive treatment to patients presenting for the first time with non-affective psychotic disorders. Details concerning the assessment and treatment protocols used by PEPP are available elsewhere ([20] or at http://www.PEPP.ca). All patients provided informed consent and the protocol was approved by the University of Western Ontario Ethics Board for Health Sciences Research.

Measures

The assessment protocol within PEPP includes completion of a SCID shortly after entry and 1 year later. The data relevant to diagnosis are based on the latter assessment. Information regarding pathways to care was collected using an instrument called the Circumstances of Onset and Relapse Schedule [28], which include some sections of the Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of Onset of Schizophrenia (IRAOS, [9]).

Estimates of the indices described below were obtained after careful review and cross referencing of available sources of information including interviews with patients, family members and clinicians who were involved in the care of the patient, and review of clinical notes. In all cases at least two sources of information were used and in over 70% of cases three sources or more were consulted. Over 80% of patients were living with their family of origin or with a spouse or partner at the time of the onset of illness. Of those who were living on their own, in all cases the family member providing information had been in regular contact with the individual. In general there was good agreement between sources concerning the indices. When reliable information was not available or there were discrepancies between sources that could not be resolved, the information was treated as missing. The assessors agreed to be cautious by classifying a variable as missing rather than using an estimate, which they considered unreliable. The dates of particular relevance to the issues being examined in this paper are the following.

Onset of early signs

This refers to the point at which there was an onset of noticeable changes, such as marked symptoms of depression or anxiety and/or clear detectable change in normal functioning. In order to be considered an early sign, theses changes had to represent a change from the individual’s previous stable level of functioning (rather than problems or concerns associated with a lifelong behaviour pattern or characteristic such as “always being socially shy and anxious”) and to generally persist up to the time of onset of psychosis. When the first noticeable changes involved positive symptoms of psychosis, this date would correspond to the initial onset of psychosis as described below. When the first signs were not psychosis, this date would be earlier than the initial onset of psychosis. The most common of these early signs were combinations of feelings of sadness/depression, substantially heightened anxiety or stress, unusual problems with memory or concentration as well as deterioration in self-care, irritability, and social withdrawal (see [28]).

Onset of psychosis

This refers to the beginning of clear symptoms of psychosis (hallucinations, delusions and/or grossly disorganized behaviour or thinking) that had duration of at least 1 week.

Recognition by family member of need for help

This refers to the point at which a family member recognized the need to seek professional help for the patient. If family members came to this recognition at different times, then the earliest date was used. Most often assistance was sought from a physician, hospital emergency service or professional counsellor such as a psychologist, social worker or school counsellor [28].

Initiation of treatment

Following the precedent of Larsen et al. [18] we defined initiation of treatment for psychosis as receiving anti-psychotic medication of a dosage and period of time (4 weeks) that would usually lead to a clinically sufficient response in non-chronic, non-treatment resistant patients, or (if shorter), the point at which remission was achieved after initiation of anti-psychotic therapy.

The above dates were used to calculate the following indices of relevance to this report. Duration of untreated illness (DUI) was the delay between onset of early signs and treatment for psychosis. The experience of psychotic symptoms can be quite episodic. As noted elsewhere [25, 30], this means that delay in treatment or duration of untreated psychosis can be calculated either in terms of time elapsed between initial onset and treatment (which we will term DUPonset) or estimated cumulative time that the individual was actively experiencing psychotic symptoms prior to treatment (DUPcum). Delay in family recognition from early signs refers to the interval between the onset of early signs and the family’s recognition of need for help. Delay in family recognition from psychosis was defined as the interval between the onset of clear psychotic symptoms and family recognition of need for help.

The above intervals were of most direct relevance to the research questions. For subsidiary analyses we also made use of two additional intervals. These were the length of early signs, which refers to the difference between the DUI and DUP onset; and the delay between family recognition and initiation of treatment. The latter index refers to the length of time between the family recognition of need for help and the initiation of treatment with an anti-psychotic.

Inter-rater reliability for each of the above indices was established based on independent assessments of 12 individuals by two raters. The intraclass correlation coefficient for all indices was 0.80 or greater.

Family history of psychotic disorders

Family history of psychotic disorder was assessed in the same fashion as Chen et al. [4] and based upon items derived from the IRAOS. Following the identification of any psychiatric illness in a first or second degree relative questions were asked about whether the informants were aware of a diagnosis that had been provided as a result of a formal psychiatric assessment. The interviewer also asked for a description of symptoms of the affected family member paying particular attention to manifestations of hallucinations, delusions, disorganization and negative symptoms. This resulted in the identification of the presence of a family history of a schizophrenia spectrum psychotic disorder for 27.2% of the cases, which is not significantly different from the 22.9% identified by Chen et al. in their sample. While this methods of identifying family history does not involve independent evaluation of the family member, it should provide a reasonable index of the family’s perception of history of psychotic disorders which is likely to be the most critical factor in influencing help seeking.

Measures of treatment delay are often skewed [22, 26], so preference was given the use of non-parametric statistical tests. The primary contrasts of family history groups were carried out using either chi-square for categorical variables or the Mann–Whitney Test for continuous variables. There are no readily available methods of sample size calculation for rank tests, so we have followed the recommendation to use the parallel parametric test (t-test) and assume that under the circumstances, the non-parametric test is at least as (and probably more) powerful [24]. These calculations indicate our sample size would yield a power of 0.80 (at 0.05 significance level) to detect an effect size of 0.50.

Results

Sample characteristics

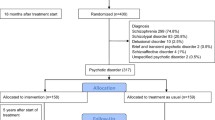

During the period of February 1998–July 2004, PEPP admitted 223 patients meeting the diagnostic criteria used by Chen et al. [4]. It was possible to complete a CORS sufficient for obtaining DUI, DUP and family history of psychotic illness on 169 (75.8%) of these cases. On 111 (65.7%) of those for whom a CORS interview occurred, it was possible to obtain reliable information regarding the time of the family’s recognition of need for help. The reasons for failures of data collection included the client leaving the program before the assessments were completed, refusal to consent to the relevant assessment or there not being sufficiently reliable information available.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and diagnosis of all those admitted and the two subsamples. Approximately three quarters of patients were males and almost 60% had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. There were no significant differences in characteristics between all those admitted during the period and the subsamples. Lengths of treatment delay are consistent with past reports [22, 25].

Family history and overall treatment delay

Table 2 presents data contrasting DUP and DUI for those with and without a reported family history of psychotic disorders. The only delay index to differ significantly with family history was the duration of untreated illness (Mann–Whitney U = 2222.0, P < 0.05) reflecting longer DUI for the positive family history group (mean = 355.8 weeks, median = 270.0) than the negative group (mean = 276.9, median = 190.9).

In order to parallel an analysis reported by Chen et al. [4], we carried out a binary comparison of those who had DUP of less than 6 months versus longer. In contrast to Chen et al., we did not find the percentage of positive family history to differ between these two groups (25.3% vs. 30%. χ2 = 0.303, n.s.).

Family history and family recognition of need for help

As noted earlier, past reports have indicated that substantial proportions of first episode psychosis patients seek help from professional services prior to the onset of actual symptoms of psychosis such as hallucinations and delusions. If a family history of psychotic disorders results in less sensitivity to non-specific early signs, we would expect it is less likely for such family members to perceive the need for help prior to the occurrence of psychosis. We examined this in the 111 cases concerning which there was information about the timing of family recognition of need for help. In 14 of the 77 cases without a family history (18.2%) this recognition occurred before the onset of psychosis, whereas the comparison figure of those with a family history was 13 of 34 (38.2%) (χ2 = 5.15, P < 0.05).

At first the above findings appear to reflect a paradox. If a longer DUI in the positive family history group is due to greater delay in family responding to early signs then one would expect fewer such families to have recognized the need for help before the onset of psychosis. This might reflect the length of time between the onset of early signs and the onset of psychosis being longer for those with a positive family history. A longer period of exposure to non-specific signs prior to psychosis could bring about both longer DUI and greater likelihood of recognition of need for help before the onset of psychotic symptoms. The mean length of time between onset of early signs of change and onset of psychosis for those without a family history was 197.7 weeks (SD 246.2) with a median of 104.6 and for those with a positive family history the mean was 259.9 (SD 241.8) and a median of 201.7. A Mann–Whitney U-test yields a significant difference between the two groups (U = 2,258.5, P < 0.05).

To further assess the possible role of differential length of non-specific symptoms between family history groups in explaining differences in DUI, we carried out a square root transformation of DUI and log transformation of length of the period between onset of early signs and onset of psychosis and then undertook a multiple regression analysis. The results of that analysis indicated that the length of early signs is a significant independent predictor of DUI (standardized β 0.823, P > 0.001), but family history was not (standardized β = 0.038, n.s.). This suggests that the difference in DUI for the family history groups is primarily due to a longer period between onset of early signs and onset of psychosis for those with a positive family history.

Table 3 shows little indication that once psychosis occurred there was any significant difference between family history groups in delay in recognition. Consistent with this are the results of a Mann–Whitney U-test contrasting the groups on the total length of time between onset of psychosis and recognition of need for help (U = 1,058.5, n.s.).

Possible effects of mode of onset or gender

Chen et al. [4] reported some evidence that the relation between positive family history and shorter DUP might be particularly prominent for those cases showing an “insidious” onset which was defined as a gradual development of an episode of psychosis over a period of more than 1 month. We therefore contrasted family history groups on both DUP indices and time to family recognition from onset of psychosis for only those patients who showed a period of greater than 1 month from early signs to onset of psychosis. In this restricted sample, the differences between family history groups still did not approach significance.

Chen et al.’s sample had a higher proportion of females than ours. We, therefore, contrasted the duration of illness and delay in recognition indices between family history groups for female patients only. The difference between history groups approached significance for DUPonset and DUPcum (U = 77, P = 0.07 and U = 82, P = 0.054). Females with a positive family history tended to have a longer DUPonset than the negative group (mean 192.7 weeks, SD 220.7, median 78.4 vs. mean 63.7, SD 117.6, median 16.4) and a longer DUPcum (mean 192.7, SD 220.7, median 78.4 vs. mean 51.2, SD 101.6, median 14.4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship of family history of psychotic disorders to both DUI and DUP. Furthermore; it is unique in having examined not just overall treatment delay, but timing of the recognition by family members of the need for help.

Our hypothesis was that there would be greater DUI in the positive family history group because of less sensitivity of such families to the need to seek help for early signs. While the prediction of greater DUI was confirmed, the anticipated mechanism was not. There was actually evidence of greater likelihood of those families with a positive history recognizing the need for help solely in response to early signs. The presence of longer DUI seems to be related more to a longer delay between onset of early signs and onset of psychosis for those with a positive family history than less likelihood of them recognizing the need for help on the basis of early signs. The finding of such a difference in length of early signs is consistent with recent evidence of poorer pre-morbid adjustment in cases of schizophrenia with positive family history [33].

With reference to the relationship of a positive family history to DUP, we failed to replicate the findings of Chen et al. [4]. Our findings are consistent with others in generally finding no significant relation between family history of psychotic disorders and DUP [6, 35]. The current sample and that of Chen et al. were similar in diagnostic breakdown and the proportion of individuals living on their own. Chen et al.’s sample is somewhat unusual in having a majority of females and a somewhat older age distribution than is typical of many first episode psychosis patients [6, 11, 13, 14]. In an effort to explore the possibility that our failure to replicate Chen et al.’s findings is due to the difference in gender, we undertook analyses on female subjects only. The results of this sub-analysis did not confirm Chen et al.’s findings; indeed they tended to be in the opposite direction.

The study of Chen et al. was carried out in a population that was described as being relatively poorly informed about symptoms of psychosis; and, therefore, direct family experience of psychosis was expected to lead to more awareness of these symptoms and reduced treatment delay. It may be that the population relevant to the current study was generally better informed and this neutralized the effect of family history on treatment seeking. Unfortunately, we have no way of directly examining the validity of this explanation.

There are limitations to the current study. The data on delay in seeking treatment and the role of family in pathways to care is, of necessity, retrospective. Great care was taken in confirming information across sources and aiming for reasonable certainty in reports, but, our estimates cannot be independently validated. Similarly, we do not have independent validation of reported family history of psychotic illness, although it is reassuring that the incidence of reported positive family history was similar to that reported by others [4].

Questions could also be raised about whether particular constellations of history in illness (such as occurrence in siblings versus parents) could differentially influence treatment delay. Our sample size and characteristics (predominantly young with very few cases of illness in siblings) did not allow for meaningful comparisons relevant to this issue.

One of the implications of this study is that we cannot assume that in those families with a history of psychosis, there will be prompt identification and treatment of new cases. Clinicians working with such families need to remind them of the need for vigilance while not causing undue alarm. Similarly, broader education initiatives for early detection cannot assume that those with more family experience of such disorders will be less prone to delays in treatment.

The data reported here also have implications for possible confounds of any relationship between delay and treatment outcome. There is evidence that those patients with a positive family history also tend to be less responsive to treatment [32, 34]. The association of having a relative with a psychotic disorder with both longer DUI and less treatment response suggests that family history needs to be carefully examined as a possible confound of any relationships between DUI and treatment outcome [16, 21].

References

Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Hutchinson J, Addington D (2002) Pathways to care: help seeking behaviour in first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 106:358–364

Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Gorman JM (1991) Awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 17:113–132

van der Heiden W, Hafner H (2000) The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 230:292–303

Chen EY-H, Dunn EL-W, Miao MY-K, Yeung W-S, Wong C-K, Chan W-F, Chen RY-L, Chung K-F, Tang W-N (2005) The impact of family experience on the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:350–356

Cougnard A, Kalmi E, Desage A, Misdrahi D, Abalan F, Brun-Rousseau H, Salmi LR, Verdoux H (2004) Pathways to care of first-admitted subjects with psychosis in South-Western France. Psychol Med 34:267–276

de Haan L, Peters B, Dingemans P, Wouters L, Linszen D (2002) Attitudes of patients toward the first psychotic episode and the start of treatment. Schizophr Bull 28:431–442

Fuchs J, Steinert T (2004) Patients with a first episode of schizophrenia spectrum psychosis and their pathways to psychiatric hospital care in South Germany. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:375–380

Gourzis P, Katrivanou A, Beratis S (2002) Symptomatology of the initial prodromal phase in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 8:415–429

Hafner H, Riechler-Rossler A, Manbracht M, Maurer K, Meissner SS, Schmidtke A, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W, an der Heiden W (1992) IRAOS: an instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 6:209–223

Hambrecht M (1995) A second case of schizophrenia in the family: is it observed differently? Eur Arch Psychiatr Clinl Neurosci 245:267–269

Harris MG, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, Purcell R, Schwartz OS, Farrelly SE, Prosser AL, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2005) The relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome: an eight-year prospective study. Schizophr Res 79:85–93

Helgason L (1990) Twenty years follow-up of first psychiatric presentation for schizophrenia: what could have been prevented? Acta Psychiatr Scand 81:231–235

Ho B-C, Alicata D, Ward DJ, Moser DJ, O’Leary DS, Arndt S, Andreasen NC (2003) Initial untreated psychosis: relation to cognitive deficits and brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatr 160:142–148

Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Razi K, Heydebrand G, Csernansky JG, DeLisi LE (2000) Lack of association between duration of untreated illness and severity of cognitive and structural brain deficits at the first episode of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatr 157:1824–1828

Johnstone EC, Crow TC, Johnson AL, MacMillan JF (1986) The Northwick Park Study of first episodes of schizophrenia. I. Presentation of the illness and problems related to admission. Br J Psychiatr 148:115–120

Keshavan MS, Haas G, Miewald J, Montrose DM, Reddy R, Schooler NR, Sweeney JA (2003) Prolonged untreated illness duration from prodromal onset predicts outcome in first episode psychoses. Schizophr Bull 29:757–769

Kohn D, Pukrop R, Niedersteberg A, Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Bechdolf A, Berning J, Maier W, Klosterkotter J (2004) Pathways to care: help-seeking behavior in first-episode psychosis. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 72:635–642

Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC (1996) First episode schizophrenia: I: early course parameters. Schizophr Bull 22:241–256

Lincoln CV, Harrigan S, McGorry PD (1998) Understanding the topography of the early psychosis pathway. Br J Psychiatr 172(suppl. 33):21–25

Malla AK, Norman RMG, McLean T, Scholten D, Townsend L (2003) A Canadian programme for early intervention for early intervention in non-affective psychotic disorders. Aust N ZJ Psychiatr 37:407–413

Malla AK, Norman R, Schmitz N, Manchanda R, Bechard-Evans L, Takhar J, Haricharan R (2006) Predictors of rate and time to remission in first-episode psychosis: a two-year outcome study. Psychol Med 36:649–658

Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T (2005) Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients. Arch Gen Psychiatr 62:975–983

McGorry PD, Krstev H, Harrigan S (2000) Early detection and treatment delay: implications for outcomes in early psychosis. Curr Opin Psychiatr 13:37–43

Norman GR, Streiner DL (2000) Biostatistics: the bare essentials. BC Decker, Hamilton

Norman RMG, Malla AK (2001) Duration of untreated psychosis: a critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med 31:381–400

Norman RMG, Lewis SW, Marshall M (2005) Duration of untreated psychosis and its relationship to clinical outcome. Br J Psychiatr 187 (suppl. 48):s19–s23

Norman R, Malla AK Pathways to care and reducing treatment delay in early psychosis. In: Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (eds) The recognition and management of early psychosis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (in press)

Norman RMG, Malla AK, Verdi MB, Hassall LD, Fazekas C (2004) Understanding delay in treatment for first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 34:255–266

Norman RMG, Scholten DJ, Malla AK, Ballegeer T (2005) Early signs in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Nerv Mental Dis 193:17–23

Norman RMG, Townsend L, Malla AK (2001) Duration of untreated psychosis and cognitive functioning in first-episode patients. Br J Psychiatr 179:340–345

Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA (2005) Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatr 162:1785–1804

Silverman JM, Mohs RC, Davidson M, Losonczy MF, Keefe RS, Breitner JC, Sorokin JE, Davis KL (1987) Familial schizophrenia and treatment response. Am J Psychiatr 144:1271–1276

St-Hilaire A, Holowka D, Cunningham H, Champagne F, Pukall M, King S (2005) Explaining variation in the premorbid adjustment of schizophrenia: the role of season of birth and family history. Schizophr Res 73:39–48

Tsuang MT (1993) Genotypes, phenotypes, and the brain. A search for common connections. Br J Psychiatr 163:299–307

Verdoux H, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalam F, Gonzales B, Pauillac P, Fournet O, Liraud F, Beauussier JP, Gaussares C, Etchegaray B, van Os J (1998) Prediction of duration of psychosis before first admission. Eur Psychiatr 13:346–352

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norman, R.M., Malla, A.K. & Manchanda, R. Delay in treatment for psychosis. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 42, 507–512 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0174-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0174-3