Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to generate normative values and to test psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for the general population of Colombia. While there are several normative studies in Europe, Latin American normative values are missing. The identification of people with mental distress requires norms obtained for the specific country.

Methods

A representative face-to-face household study (n = 1,500) was conducted in 2012. The survey questionnaire contained the HADS, several other questionnaires, and sociodemographic variables.

Results

HADS mean values (anxiety: M = 4.61 ± 3.64, depression: M = 4.30 ± 3.91) were similar to those reported from European studies. Females were more anxious and depressed than males. The depression scale showed a nearly linear age dependency with increasing scores for old people. Mean scores and percentiles (75 and 90 %) are presented for each age decade for both genders. Both anxiety and depression correlated significantly with the total score of the multidimensional fatigue inventory and with the mental component summary score of the quality of life questionnaire SF-8. Internal consistency coefficients of both scales were satisfying, but confirmatory factorial analysis results only partially supported the two-dimensional structure of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

This study supports the reliability of the HADS in one Latin American country. The normative scores can be used to compare a patient’s score with those derived from a reference group. However, the generalizability to other Latin American regions requires further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety and depression are frequently observed in patients suffering from physical diseases, with an enormous burden on the patients and on the society [1]. These symptoms, however, often remain undetected by physicians, with detection rates below 50 % [2, 3]. Several screening instruments have been developed to identify patients with increased distress, e.g., the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Developed by Zigmond and Snaith [4], this questionnaire has been translated into many languages and used in many clinical studies, especially in cardiology and oncology. Compared with multiple other questionnaires on anxiety, depression, and general distress, applied to cancer patients, the HADS obtained the best overall evaluation in a review with 132 studies [5], while another meta-analysis with 41 studies found out that the HADS has a good (but not superior to other screening instruments) case-finding ability. A large Norwegian study [6] established an association between HADS depression and all-cause mortality rate. Many studies have been performed to test the psychometric properties of the instrument [7], especially the dimensional structure. A recent review [8] found that exploratory factor analyses generally confirmed the bidimensional structure, while confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) in most cases support three-dimensional solutions, e. g., [9–12]. However, these three-dimensional solutions are not identical. In clinical practice, the original scale structure (anxiety and depression) is maintained in most cases. However, sometimes a summarizing score over all 14 items is calculated, indicating general mental distress [13]. The HADS was also tested with item response theory [14–16].

The interpretation of individual HADS scores requires the availability of normative data obtained from a sample of the general population. Such normative studies have been performed in several countries: Germany [17], UK [18, 19], Norway [20] (depression subscale only), Sweden [21], Hong Kong [22], and South Korea [23]. There are some remarkable differences between the countries. Anxiety mean values range from 3.6 [22] (Hong Kong) to 6.4 [19] (UK), while the depression means were found between 3.3 [22] (Hong Kong) and 6.6 [23] (Korea), with the European countries in between. Age and sex differences were also investigated in these studies. Most investigations found increasing depression mean scores with increasing age, especially in the largest study with more than 60,000 people in Norway [20], while the age dependency of anxiety was less pronounced. Sex differences were also not identical in the investigations. Women generally reported more anxiety than men in most studies, with differences ranging from 0.5 [24, 25] to 2.1 [21] points, whereas depression differences between males and females were small. We cannot give reasons for the differences in the study results. However, these discrepancies, even between European countries with similar social structures, indicate the limited degree of generalizability and the need for normative studies in other countries.

Though the HADS has been used in Latin America in several clinical investigations (e.g., [26–29]), normative data has yet to be made available for this part of the world with about 500 million inhabitants. Anxiety and depression can be considered components of quality of life. Latin American normative values have been published for the quality of life instruments WHOQOL-BREF [30] (Brazil), SF-36 [31] (Mexico), and SF-6D [32] (Brazil). An international study [33], including Argentina and Brazil, compared mean values of the general population with the WHOQOL-BREF. Generally speaking, these studies did not detect great differences between Latin America and Europe or Northern America with respect to mean scores of the mental health components of the quality of life instruments. However, to date, HADS norms for Latin American countries are missing, and it is unknown whether age and sex differences are similar to those found in Europe and Northern America.

The aim of this study was to provide HADS normative values for the Colombian general population, to test age and sex differences, and to explore psychometric properties of this questionnaire.

Methods

Study design

The study sample consists of adult people (18 years and above) of the general population of Colombia. The Ethics Committee at the Universidad de los Andes approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research market company “Brandstrat Inc.” conducted the interviews in eight main cities of Colombia: Bogotá, Cali, Medellín, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga, Pereira, Cartagena, and Manizales. Trained interviewers performed the survey. They asked the eligible participants to take part in the study, and in case of affirmation they gave them a booklet with several questions and questionnaires and asked them to fill them in. After finishing, the interviewers controlled the booklet for missing data and asked the people to complete the questionnaires in case of missing data (except household income). The total duration was about 45 min. Each Colombian city is divided into barrios (quarters) with different mean socioeconomic strata (SES) of the inhabitants (SES ranging from 1 = very low to 6 = very high), which are characterized by the mean socioeconomic level of the inhabitants. The sampling procedure adopted in this survey assured that each stratum (with corresponding barrios) was representatively included in the sample. Within each barrio, the participants were randomly selected. In case of non-response, another eligible participant from the same stratum was asked. This technique yielded a stratum distribution in the study sample identical with that of the general population. Due to this procedure, the resulting sample can be assumed to be representative of the population of Colombia, living in private houses. A total of 2,372 people were contacted, and finally 1,500 people responded with complete data sets, resulting in a response rate of 63 %. The interviewers did not obtain data in case of non-participation. Therefore, we have no data on reasons of non-participation. As an incentive for collaboration in the study, a brochure with information about healthy lifestyles was given to the participants.

Questionnaires

The HADS consists of 14 items, seven items indicating anxiety and seven items indicating depression. The answer format offers four options, scored with values from 0 to 3. This results in scale values between 0 and 21 for each scale. Three ranges were defined by the original test authors: 0–7 (non-cases), 8–10 (doubtful cases), and 11–21 (cases). Several studies also use a HADS total score, simply summing up the anxiety and depression items. Several cut-offs for this total score have been proposed by different researchers, based on sensitivity and specificity calculations. In the review article [7], 16 papers are listed with 11 different cut-off scores. Singer and colleagues [13] recently recommend the cut-off score of 13+ (“medium model”), which is nearly in the middle of the cut-off scores recommended in the literature. We used the Spanish version of the HADS [34], but made a minor cultural adaptation after performing a pretest. We replaced the wording “aleteo en el estómago” with “mariposas en el estómago” which is an expression commonly used in Colombia and is, therefore, easily understood by our population.

To assess construct validity, the survey also included several other questionnaires:

GHQ-12: General Health Questionnaire [35]. This 12-item questionnaire is a validated indicator of psychological distress. In this study, we used the one-dimensional Likert scaling (0–1–2–3). Points were summed to a global score ranging from 0 to 36.

MFI-20: Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [36]. The MFI-20 covers five dimensions of fatigue: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue. We calculated a sum score for all 20 items.

LOT: Life Orientation Test [37]. This questionnaire is a six-item scale (with four filler items), containing three items each for positive and negative general life expectations. As in the original conceptualization, in this study the LOT was used as a uni-dimensional scale with the poles pessimism and optimism.

SF-8: short form health survey (eight items) [38]. The shortest member of the SF family is the SF-8. It generates a health profile of eight scores describing health-related quality of life, which is summarized into physical component and mental component summary scores.

FLZ: Questions on Life Satisfaction [39]. This questionnaire assesses general life satisfaction in eight dimensions: friends/acquaintances, leisure activities/hobbies, health, income/financial security, occupation/work, housing/living conditions, family life/children, and partner relationship/sexuality. In addition, the subjective importance of each of the dimensions is assessed. Finally, the total FLZ score is calculated as the sum of the satisfaction scores of the eight dimensions, weighted by their importance ratings.

Data analysis

The influence of age and gender on anxiety and depression was tested with two-factorial ANOVAs. The 75 and 90 % percentiles are those scores for which 75 or 90 % of the respondents reach this or a lower score. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to calculate the association between the HADS scores and the scales of the other questionnaires. Internal consistency was determined with Cronbach’s alpha [40].

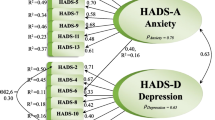

Confirmatory factorial analysis was performed with Mplus. We examined three models: the two-dimensional standard model (anxiety and depression), the one-dimensional model (mental distress, no segmentation into subscales) [41], and the so-called bifactorial model, including a broad general factor, onto which all items load, and two conceptually narrower factors onto which items with related content (anxiety or depression) load (cf. [12], Fig. 2, model 9). We used the following criteria: bayesian information criterion (BIC), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [42], comparative fit index (CFI) [43], and tucker lewis index (TLI) [44]. RMSEA <0.05 indicates a “close fit”, RMSEA between 0.05 and 0.08 a “reasonable fit”, and RMSEA >0.10 an “unacceptable fit”. TLI and CFI are coefficients that describe how well a model fits the data relative to a model that assumes only sampling errors to explain the covariance of the observed variables. According to Hu and Bentler [45], CFI and TLI should be greater or equal 0.95.

Results

Description of the sample

Sociodemographic characteristics of the final sample are given in Table 1. The sample is roughly representative of the adult Colombian population concerning age, gender, and civil status. In the right part of Table 1, census data of the total Colombian population are given, provided by the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE, Colombian Statistical Administrative Office) [46]. The percentages for the sex and age categories obtained in our sample are similar to those of the general population. The DANE data sets concerning education and employment status cannot be used here, because they also include children. With the exception of household income, there were no missing data since the interviewers controlled the completeness of the questionnaires and asked the participants to complement the questionnaire in the case of missing values.

Normative data

The HADS mean scores for the total sample are 4.61 (SD = 3.64) (anxiety) and 4.30 (SD = 3.91) (depression). Table 2 presents the mean scores for age groups and both genders separately, together with 75 and 90 % percentiles. Females are more anxious (diff = 0.4) and more depressed (diff = 0.5) than males. There is a roughly linear age trend for depression (both genders), but not for anxiety. Table 3 shows the results of the two-factorial ANOVA. The greatest effect (p < 0.001) is the influence of age on depression.

An alternative way to express age and gender differences of anxiety and depression is presented in Table 4. The figures indicate the percentages of subjects whose score is equal or greater than the cut-off given in the left column. The values of cut-off 8+ represent all subjects with 8+ and not only those between 8 and 10.

Influence of sociodemographic variables on anxiety and depression

People with high educational level, employment, and high income show lower rates of anxiety and depression. Depression mean score group differences are more pronounced than anxiety differences. Living with/without a partner has nearly no influence on anxiety and depression. Among the sociodemographic variables, education has the highest impact, with an effect size of d = 0.43 in the depression subscale. Though anxiety and depression mean scores increase with increasing numbers of chronic diseases, due to small sample sizes of the groups with chronic conditions the group differences are not statistically significant (Table 5).

Psychometric properties

The correlations between the HADS scales and other scales (construct validity) are presented in Table 6. HADS anxiety and depression are positively correlated with questionnaires on fatigue (MFI-20) and mental disorders (GHQ-12), and negatively correlated with quality of life, life satisfaction and optimism. There are only marginal differences between anxiety and depression in the pattern of the correlations.

The following coefficients of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) were obtained: anxiety (α = 0.76), depression (α = 0.78), and total score (α = 0.86). The part-whole corrected item-scale correlations for the anxiety (A) and depression (D) items were as follows: r = 0.52 (A1), r = 0.59 (A3), r = 0.50 (A5), r = 0.44 (A7), r = 0.30 (A9), r = 0.49 (A11), r = 0.57 (A13); r = 0.56 (D2), r = 0.61 (D4), r = 0.49 (D6), r = 0.40 (D8), r = 0.54 (D10), r = 0.54 (D12), and r = 0.38 (D14). Anxiety and depression were correlated with r = 0.67.

The CFA yielded the following results: two-dimensional standard model (df = 76): BIC = 46778, SRMR = 0.047, RMSEA = 0.071, CFI = 0.899, and TLI = 0.880; one-dimensional model (df = 77): BIC = 46923, SRMR = 0.050, RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.873, and TLI = 0.850, and bifactorial model (df = 63) [12] BIC = 46,682, SRMR = 0.039, RMSEA = 0.062, CFI = 0.937, and TLI = 0.909.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to test psychometric properties of the HADS questionnaire in a Latin American country and to provide normative values. The mean scores of anxiety and depression were within the range obtained in studies from other countries. The anxiety mean score (M = 4.6) was nearly identical with that of the German [17] (M = 4.7) and the Swedish [21] (M = 4.5) study, while the mean score of Hong Kong [22] (M = 3.6) was lower, and the scores of Korea [23] (M = 5.3) and the UK [18] (M = 6.4) were higher. Concerning depression, the mean score of this Colombian study (M = 4.3) was higher than those of Hong Kong (M = 3.3), Norway (M = 3.5), UK (M = 3.7), and Sweden (M = 4.0), but lower than those of Germany (M = 4.7) and Korea (M = 6.6). In contrast to Korea, where higher levels of mental distress were reported, the values obtained in Colombia were generally in the range of the European studies.

Age and sex effects were only partially identical with those obtained in the other studies. Women reported significantly more anxiety (p < 0.05) and depression (p < 0.01) than men, while in most other studies there is only a sex difference in anxiety. As in other studies, depression markedly increases with age, for both sexes. This justifies presenting normative values separately for sex and age groups. In contrast to the German study, linear models did not seem to be appropriate, since in anxiety and depression there were non-linear age relationships. Therefore, it was not appropriate to present beta coefficients for the description of age dependency.

Researchers who prefer to express the burden of anxiety and depression in terms of percentages of subjects exceeding a certain cut-off score can see in Table 4 that about 25 % of the males and about 30 % of the females suffer from heighted mental distress (total score, cut-off 13+). Since there is no convention about an appropriate cut-off point, it is difficult to compare these results with other studies that used different cut-offs. However, Table 4 can help translate the mean scores (given in Table 2) into percentages of “cases” (given in Table 4).

HADS scores correlated negatively with quality of life (SF-8), life satisfaction (FLZ) and optimism (LOT), while the correlations were positive for fatigue (MFI-20) and mental distress (GHQ-12). There were only marginal differences in the correlation pattern between anxiety and depression. The highest coefficients were obtained between HADS and MFI-20 (fatigue), which may be, at least in part, due to the higher number of items of the MFI-20, compared to the other questionnaires. The correlation coefficients of the HADS total score were generally higher than those of the single scales (anxiety and depression). Together with the high correlation between anxiety and depression (r = 0.67) and the high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86) of the total scale we conclude that the use of the total score, albeit not recommended by the original test authors, is a useful measure for mental distress and can by applied in clinical practice. CFA results only partially supported the two-dimensional structure of the HADS. The model fit was best for the bifactorial model, including both subscales and the general factor. The one-dimensional model showed the lowest fit coefficients, and the fit of the two-dimensional standard model was in between. While the RMSEA criterion for this model was acceptable, the values for the TLI and CFI were below the criterion of 0.95.

All items contributed to the reliability of the scales, with two exceptions, items A9 and D14. These two items neither enhanced nor diminished Cronbach’s alpha. Taken together, the results of the CFA and reliability analyses justify the use of the HADS in the original way, applied to the population under study.

The study has several limitations. A standard diagnostic interview for anxiety and depression was not included. The questionnaires used to assess validity of the HADS have not been validated yet for the Colombian population. Though in Colombia most people live in cities, the underrepresentation of rural areas might cause a bias. However, the sampling method assured that the barrios with their different socioeconomic levels were representatively included in the examination. The generalizability of the study results may be a matter of debate. Even in Western European studies there were considerable differences in mean HADS scores and in age and gender dependencies. Therefore, it is difficult to assess to what degree the results reported here can be generalized to Latin America. Though some psychometric properties of the HADS in the Colombian sample were not convincing, we believe that it is useful to maintain the internationally accepted scale structure. If we had created new subscales according to factorial analyses, the results (mean scores, age and gender differences, normative values, correlations with other questionnaires) could not be compared with those reported in other investigations.

Clinicians in Colombia can use the reference data presented here to assess the degree of psychological distress of their patients. The psychometric analyses showed that the standard use of the HADS is also appropriate in Colombia. Normative and psychometric studies in other Latin American countries are needed to assess the generalizability of the study results.

References

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, de Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takeshima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayyad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, de Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen YC, Huang YQ, Zhang MY, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Alonso J, Brugha TS, Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S (2004) Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the world health organization world mental health surveys. JAMA 291(21):2581–2590

Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Grafe K, Kroenke K, Quenter A, Zipfel S, Buchholz C, Witte S, Herzog W (2004) Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. J Affect Disord 78(2):131–140

Singer S, Brown A, Einenkel J, Hauss J, Hinz A, Klein A, Papsdorf K, Stolzenburg JU, Brähler E (2011) Identifying tumor patients’ depression. Support Care Cancer 19(11):1697–1703

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Luckett T, Butow PN, King MT, Oguchi M, Heading G, Hackl NA, Rankin N, Price MA (2010) A review and recommendations for optimal outcome measures of anxiety, depression and general distress in studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses. Support Care Cancer 18(10):1241–1262

Mykletun A, Bjerkeset O, Overland S, Prince M, Dewey M, Stewart R (2009) Levels of anxiety and depression as predictors of mortality: the HUNT study. Br J Psychiatry 195(2):118–125

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77

Cosco TD, Doyle F, Ward M, Mcgee H (2012) Latent structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: a 10-year systematic review. J Psychosom Res 72(3):180–184

Caci H, Bayle FJ, Mattei V, Dossios C, Robert P, Boyer P (2003) How does the Hospital and Anxiety and Depression Scale measure anxiety and depression in healthy subjects? Psychiatry Res 118(1):89–99

Dunbar M, Ford G, Hunt K, Der G (2000) A confirmatory factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale: comparing empirically and theoretically derived structures. Br J Clin Psychol 39:79–94

Friedman S, Samuelian JC, Lancrenon S, Even C, Chiarelli P (2001) Three-dimensional structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a large French primary care population suffering from major depression. Psychiatry Res 104(3):247–257

Norton S, Cosco T, Doyle F, Done J, Sacker A (2013) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: a meta confirmatory factor analysis. J Psychosom Res 74(1):74–81

Singer S, Kuhnt S, Götze H, Hauss J, Hinz A, Liebmann A, Krauß O, Lehmann A, Schwarz R (2009) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale cut-off scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer 100(6):908–912

Cosco TD, Doyle F, Watson R, Ward M, Mcgee H (2012) Mokken scaling analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 34(2):167–172

Kendel F, Wirtz M, Dunkel A, Lehmkuhl E, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V (2010) Screening for depression: rasch analysis of the dimensional structure of the PHQ-9 and the HADS-D. J Affect Disord 122(3):241–246

Smith AB, Wright EP, Rush R, Stark DP, Velikova G, Selby PJ (2006) Rasch analysis of the dimensional structure of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Psychooncology 15(9):817–827

Hinz A, Brähler E (2011) Normative values for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the general German population. J Psychosom Res 71(2):74–78

Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP (2001) Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 40:429–434

Crawford JR, Garthwaite PH, Lawrie CJ, Henry JD, MacDonald MA, Sutherland J, Sinha P (2009) A convenient method of obtaining percentile norms and accompanying interval estimates for self-report mood scales (DASS, DASS-21, HADS, PANAS, and sAD). Br J Clin Psychol 48:163–180

Stordal E, Kruger MB, Dahl NH, Kruger O, Mykletun A, Dahl AA (2001) Depression in relation to age and gender in the general population: the Nord-Trondelag health study (HUNT). Acta Psychiatr Scand 104(3):210–216

Jorngarden A, Wettergen L, von Essen L (2006) Measuring health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults: Swedish normative data for the SF-36 and the HADS, and the influence of age, gender, and method of administration. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:91. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-4-91

Wong WS, Fielding R (2010) Prevalence of chronic fatigue among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a population-based study. J Affect Disord 127(1–3):248–256

Yun YH, Kim SH, Lee KM, Park SM, Kim YM (2007) Age, sex, and comorbidities were considered in comparing reference data for health-related quality of life in the general and cancer populations. J Clin Epidemiol 60(11):1164–1175

Lisspers J, Nygren A, Soderman E (1997) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD): some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 96(4):281–286

Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Sanne B (2006) Are men more depressed than women in Norway? Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. J Psychosom Res 60(2):195–198

Yu LS, Chojniak R, Borba MA, Girao DS, Lourenco MTDP (2011) Prevalence of anxiety in patients awaiting diagnostic procedures in an oncology center in Brazil. Psychooncology 20(11):1242–1245

Soares GLF, Freire RC, Biancha K, Pacheco T, Volschan A, Valenca AM, Nardi AE (2009) Use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in a cardiac emergency room: chest pain unit. Clinics 64(3):209–214

Carod-Artal FJ, Ziomkowski S, Mesquita HM, Martinez-Martin P (2008) Anxiety and depression: main determinants of health-related quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Related Disord 14(2):102–108

Gavito MD, Ledezma P, Morales J, Villalba J, Ortega-Soto HA (1999) Effect of induced relaxation on pain and anxiety in thoracotomized patients. Salud Ment 22(5):24–27

Cruz LN, Polanczyk CA, Camey SA, Hoffmann JF, Fleck MP (2011) Quality of life in Brazil: normative values for the WHOQOL-BREF in a southern general population sample. Qual Life Res 20(7):1123–1129

Duran-Arenas L, Gallegos-Carrillo K, Salinas-Escudero G, Martinez-Salgado H (2004) Towards a Mexican normative standard for measurement of the short format 36 health-related quality of life instrument. Salud Publica Mex 46(4):306–315

Cruz LN, Camey SA, Hoffmann JF, Rowen D, Brazier JE, Fleck MP, Polanczyk CA (2011) Estimating the SF-6D value set for a population-based sample of Brazilians. Value Health 14(5):S108–S114

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA (2004) The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 13(2):299–310

Mingote JC, Jiménez Arriero MA, Osorio Suárez R, Palomo T (2004) Suicidio: asistencia clínica. Guía práctica de psiquiatría médica, Madrid

Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C (1997) The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 27(1):191–197

Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, Dehaes JCJM (1995) The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI): psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 39(3):315–325

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW (1994) Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. J Pers Soc Psychol 67(6):1063–1078

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B (2001) How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8™ health survey. QualityMetric Incorporated, Lincoln

Henrich G, Herschbach P (2000) Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZ(M)): a short questionnaire for assessing subjective quality of life. Eur J Psychol Assess 16(3):150–159

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Rammstedt B, John OP (2007) Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. J Res Pers 41(1):203–212

Steiger JH (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res 25(2):173–180

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88(3):588–606

Tucker LR, Lewis C (1973) Reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 38(1):1–10

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadistica (DANE) (2013). http://www.dane.gov.co

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the “Fondo de Promoción para Profesores Asistentes” (FAPA-Fund to promote research of Assistant Professors) awarded to Carolyn Finck by the Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. The funding source had no role in designing the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinz, A., Finck, C., Gómez, Y. et al. Anxiety and depression in the general population in Colombia: reference values of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 49, 41–49 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0714-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0714-y