Abstract

Objective

The objective of this paper is to inform choice of optimal patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of anxiety, depression and general distress for studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogenous cancer diagnoses.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to identify all PROMs used to assess anxiety, depression and general distress in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions for people with cancer published between 1999 and May 2009. Candidate PROMs were evaluated for content, evidence of reliability and validity, clinical meaningfulness, comparison data, efficiency, ease of administration, cognitive burden and track record in identifying treatment effects in RCTs of psychosocial interventions. Property ratings were weighted and summed to give an overall score out of 100.

Results

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scored highest overall (weighted score = 77.5), followed by the unofficial short-form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS), the POMS-37 (weighted score = 60), and the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and original POMS (weighted score = 55 each).

Conclusions

The HADS’ efficiency and substantial track record recommend its use where anxiety, mixed affective disorders or general distress are outcomes of interest. However, continuing controversy concerning the HADS depression scale cautions against dependence where depressive disorders are of primary interest. Where cost is a concern, the POMS-37 is recommended to measure anxiety or mixed affective disorders but does not offer a suitable index of general distress and, like the HADS, emphasises anhedonia in measuring depression. Where depression is the sole focus, the CES-D is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety, depression and distress are commonly measured as outcomes in research evaluating psychosocial interventions for people with cancer. While blinded diagnostic interviews offer standardised data on the proportion of patients with clinical disorders, this approach is resource intensive and limits the power of between-group analyses. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) provide a popular alternative that can yield continuous data on lower as well as higher ranges of disorders with low resource requirements. Unfortunately, however, there is no accepted gold standard PROM for anxiety, depression or distress, and prevalence varies according to the PROM used. Choosing the most appropriate PROM requires appraisal of content, psychometric properties, track record, interpretability and practical issues (e.g. patient burden, language availability and cost) with reference to a specific research context. The only previous, comprehensive review in oncology evaluated questionnaires for use in screening women with breast cancer rather than outcome measurement in cancer more generally [1]. While evidence from screening is important in establishing that scores are clinically meaningful and assists with their interpretation, a PROM’s suitability as an outcome measure is also dependent on it being responsive to change.

The current authors set out to identify optimal PROMs of anxiety, depression and distress for evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adult patients receiving active treatment for heterogeneous cancers. Recommendations are made within the context of PROMs’ advantages and disadvantages for different applications.

Methods

A review was designed to evaluate candidate PROMs against the following criteria:

-

Criterion A:

Suitability for people undergoing active treatment for cancer of any type and stage;

-

Criterion B:

Reliability and validity in English-speaking cancer patients;

-

Criterion C:

Track record in identifying treatment effects in randomised control trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions;

-

Criterion D:

Clinical meaningfulness of scores;

-

Criterion E:

Availability of comparison data from cancer and general populations;

-

Criterion F:

Efficiency (number of items and number of constructs assessed);

-

Criterion G:

Ease of administration and cognitive burden.

The review proceeded in six steps:

-

1.

Identification of all anxiety, depression and distress PROMs used in RCTs of psychosocial interventions for English-speaking cancer patients published since 1999;

-

2.

Rapid filter against criteria A and B to select promising candidate questionnaires;

-

3.

Description of candidate PROMs;

-

4.

Detailed review of evidence for reliability and validity ;

-

5.

Review of capacity to detect effects in RCTs of psychosocial interventions;

-

6.

Synthesis of information collected in Steps 1 through 5 aimed at developing recommendations against the criteria above.

Step 1: identification of anxiety, depression and general distress PROMs

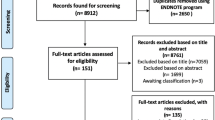

Systematic review strategy

The following databases were searched in May, 2009: Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, AMED, CENTRAL and Cinahl. Further RCTs were sought via review reference lists [2–21]. The systematic review was limited to results from English-speaking samples to minimise problems in generalising results across languages and cultures. Assuming that methodology has developed and more measures have become available over time, we focused on the previous 10 years to reduce the prominence of PROMs that have become obsolete.

Psychosocial interventions were defined and searched for using a list collated by Jacobsen and Jim ([14], p.217). This list was supplemented with search terms used in other systematic reviews [14–22].

Where reports did not describe the study language(s) or location(s), author affiliations to institutions in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, UK and USA were assumed to indicate English-speaking participants. International studies that included a sample from one or more of these countries were included.

In the psycho-oncology literature, the terms anxiety and depression are generally used to refer to clinical diagnoses. Distress is less well defined and is often used as an umbrella term for any multi-factorial, unpleasant emotional experience [23]. In keeping with this general concept of distress, PROMs described as assessing mood, emotion or stress were included alongside those explicitly described as distress measures. We excluded PROMs assessing clearly defined psychological constructs other than, contributory to or component of general distress such as coping, adjustment, self-esteem, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or the emotional domain of quality of life. Because anxiety and depression are included within the continuum of general distress, scales that combined these constructs with other emotional experiences were included pending analysis of content at Step 3 and characterisation of psychometric properties at Step 4.

Step 2: rapid filtering

Samples of candidate PROMs identified in Step 1 and current, alternative versions (e.g. short-forms) were obtained together with supporting information from manuals and websites.

Candidates were filtered against criterion A via an item-by-item review of their contents. PROMs were excluded if (a) they were deemed suitable for use only in specific populations or (b) they comprised one-third or more items likely to be confounded by symptoms and side effects (e.g. somatic symptoms, cognitive functioning, restlessness, sexual interest) or concerns ubiquitous in certain cancer groups (e.g. preoccupation with health or mortality). The rationale for excluding PROMS with somatic content a priori was that evidence for sound performance in one clinical context could not be generalised to all cancer types, stages and treatments. One-third of the items was agreed by the authors prior to review as a proportion at or above which problematic items would have the potential to seriously compromise scales in some settings.

To pass rapid filtering against criterion B, PROMs were required to have at least some published data concerning reliability and validity in an English-speaking cancer sample. Types of reliability of interest were internal consistency, test–retest reliability and inter-rater reliability between patients and proxies; types of validity were content, internal, convergent/divergent, discriminant, criterion and predictive. Psychometric articles were identified via manuals and websites and through further searches of Medline and PsycINFO using the name and acronym of each candidate PROM combined with the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms ‘neoplasms’ and ‘psychometrics’ and the key words ‘neoplasm$’ and ‘psychometric$ OR valid$ OR reliab$’. Further articles were identified via the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews. A detailed review of evidence for psychometric properties was postponed until Step 4.

Step 3: description of candidate PROMs

A description of each PROM meeting criteria in Step 2 was compiled from relevant articles, websites, publications and manuals. Information included PROM content, number of items, time to administer, response options, recall period, scoring, translation availability, licensing requirements and costs. The content of PROMs was compared with DSM-IV-TR criteria [24] for generalised anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder as a method complementary to psychometric evidence reviewed at Step 4 for delineating measures of general distress from those of anxiety and depression. A thesaurus was used to map between terms with similar meanings.

Step 4: review of evidence for reliability and validity

Quality of evidence for reliability and validity, responsiveness and information to assist with interpretation of scores was evaluated using a checklist adapted from the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) [25] and the Australian-developed Dementia Outcomes Measurement Suite (DOMS) project checklist [26].

Evidence for each property was independently evaluated by two reviewers until inter-rater reliability (kappa > 0.60) was achieved on at least 25 rating pairs. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Step 5: review of capacity to detect effects of psychosocial interventions

PROM capacity to identify effects in RCTs of psychosocial interventions was evaluated via reference to studies identified in Step 1. RCTs using candidate PROMs were identified and subjected to further exclusion criteria aimed at reducing limitations due to flawed design and methodology. Studies were excluded if they had an overall sample size of less than ten or had an attrition of more than 15% from baseline [27], except where evidence was provided that drop-out was unlikely to bias results. RCTs that used more than one candidate PROM were exempt from these exclusion criteria because of the information they provided about relative performance.

Reports were reviewed to identify instances where a candidate questionnaire had demonstrated an effect size (ES) of at least 0.2 [28–30]. We used ES because it provides a standard unit for comparison across studies and, unlike statistical significance, is independent of sample size. Effect sizes were calculated as the difference between changes in group mean scores from baseline to follow-up divided by the pooled standard deviation at baseline. Conventionally, an ES of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate and 0.8 large [31]. Studies where no ES ≥ 0.2 was identified were treated as uninformative because the intervention or research design may have been at fault rather than the PROM. Inadequacy of a given PROM was inferred only where an ES of ≥0.2 was observed on another measure assessing a similar construct.

To determine if different interventions might be best evaluated by different PROMs, we compared performance across intervention types. Interventions were categorised by three authors using an adapted version of the classification proposed by Jacobsen and Jim [14].

Step 6: synthesis and overall ratings

Information obtained in Steps 1 to 5 was synthesised to compare candidate PROMs against criteria B through G. A summary score for each PROM was generated by two reviewers using the system in Table 1. Each property was assigned a raw, categorical score of 0, 5 or 10. Raw scores for each property were then weighted according to the relative importance perceived by the authorship team. Ratings were intended to rank the PROMs rather than place them on an interval scale. Cost per use was excluded from overall scores due to variation between countries and dependency on study resources. Ease of administration and cognitive burden were evaluated by the two reviewers based on trial administrations of each PROM and item-by-item reviews concerning wording, recall period and response options in each case.

Results

Step 1: identified PROMs

Altogether, 173 psychosocial RCT interventions were identified. Of these, 132 assessed anxiety, depression and/or distress by means of a total of 30 PROMs (Table 2).

Step 2: PROMS excluded by rapid filtering

Total scores on the SCL-90-R, BSI-53/18, MHI-38, GHQ-28 and POMS-65/Bi-Polar/30 and the unofficial short-form, the POMS-37, were discounted as distress measures because they are generated through summation of subscales assessing a range of psychological constructs, many of which have a somatic emphasis.

Table 3 gives information about other scales excluded during filtering.

Step 3: description of candidate PROMs

PROMs passing rapid screening for criteria A and B at Step 2 are detailed in Table 4.

Table 5 summarises item-by-item content for each scale and compares these with terms in the DSM-IV-TR criteria [24]. While there are overlaps between the criteria for generalised anxiety disorder and major depression, the content of all candidate anxiety and depression scales emphasises the disorder which they were designed to assess. All distress measures except the DT place heavier emphasis on depressive symptoms than those associated with anxiety.

Step 4: review of evidence for reliability and validity

Thirty eight articles were amenable to evaluation using the checklist. Inter-rater reliability of kappa > 0.60 was achieved for internal consistency (kappa = 0.71), criterion validity (kappa = 0.82), discriminant validity (kappa = 0.63) and convergent validity (kappa = 0.67). Other properties were reported too infrequently for inter-rater reliability to be properly assessed. No articles were found reporting on inter-rater reliability, content validity or floor and ceiling effects for any PROM. Ratings of these articles are summarised in Table 6.

Step 5: review of capacity to detect effects of psychosocial interventions

One hundred and five RCTs identified in Step 1 used a candidate measure meeting both criteria in Step 2. Of these, 63 studies were excluded due to small sample size or attrition >15%. Articles reporting the remaining 42 trials were reviewed for information on samples, interventions and ESs for each PROM (Table 7).

Based on the range of interventions in which an ES of ≥0.2 has been identified by each PROM, broad-scale utility for intervention studies is best supported for the HADS (Table 8). The exception is exercise/physical related complementary and alternative medicine, for which only the POMS-65 has identified an intervention effect.

Step 6: synthesis and overall ratings

Table 9 provides summary ratings against criteria A through G using the weighted checklist (Table 1 above).

Discussion

The current review set out to evaluate measures of anxiety, depression and distress with the aim of informing PROM selection for studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scored highest overall (weighted score = 77.5), the unofficial short-form, Profile of Mood States-37 (POMS-37), second (weighted score = 60), and the original POMS (POMS-65) and Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) joint third (weighted score = 55).

HADS

The HADS scored highest overall due to the wealth of evidence for its psychometric properties and its efficiency in providing scores for anxiety, depression and distress using only 14 items. However, questions have been raised about the role of the HADS overall score (HADS-T) relative to HADS-A and HADS-D, the implications of the HADS’ avoidance of somatic content, its emphasis on anhedonia in evaluating depression, and appropriate scale cut-offs. Each of these issues will be discussed in turn.

Although the HADS manual [32] advises against generating a total score, the HADS-T has been widely used both in screening and outcome measurement as an index of overall distress. Content analysis at Step 3 suggests that only three items in the HADS-A and none in the HADS-D assess emotional experiences distinct from those defining generalised anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. However, several studies have found the HADS-T to be superior to one or both subscales in identifying clinical levels of distress variously defined [33–37]. Rasch analyses of data both from cancer patients [36] and patients attending musculoskeletal rehabilitation [38] have also been supportive of the HADS-T, although results from factor analyses have been more mixed [33,39–42]. The HADS-T was reported too infrequently in the RCTs reviewed here to comment on its relative responsiveness. However, on balance, we decided to accord the HADS-T the status of a measure of general distress pending future psychometric evaluation.

The HADS’ omission of somatic items is intended to avoid confounding psychological symptoms with disease or treatment. This aptitude has been confirmed in breast cancer by a factor analysis that found all items to load more strongly onto a psychological than somatic factor [40]. However, while the HADS has performed well as a screening measure in samples with poorer health status and those on active treatment, it has also performed surprisingly well in those who were disease-free and the general population, and relatively poorly in those with metastatic or progressive disease [33,37,43–45].

Unexpectedly poor performance in advanced cancer may be explicable in terms of the HADS’ emphasis on anhedonia, which may occur in this group for reasons other than depression [33]. While anhedonia is an important feature of major depression, there is concern that the HADS’ may have limited sensitivity to minor depression or adjustment disorder with depressed mood [1]. Consistent with this concern are several studies showing the HADS to be better at screening for anxiety than for depression [46–48]. However, a recent meta-analysis across language versions found the HADS-D to be superior to both the HADS-A and HADS-T in ruling out, and similar in ruling in, cases of mixed affective disorders (depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders combined; fraction-correct scores = HADS-D 78.3%; HADS-A 65.9%; HADS-T 72.6%) [49]. In the current review, the HADS-D was also found to perform comparably to the other scores in identifying intervention effects in RCTs of psychosocial interventions. As a result, we recommend continued use of the HADS-D in combination with the HADS-A and HADS-T where mixed affective disorders are the outcome of interest.

Optimal cut-offs for the HADS have varied between studies, with those recommended by its developers performing poorly in some cases [46]. Data from different studies are difficult to compare given variation in the prevalence of anxiety and depression between samples. Most informative are comparisons between more than one candidate measure in the same sample. Results from four studies of this type are available, all of which have included the HADS (see Table 10). The HADS has performed better than or comparably with other measures in nearly all cases.

Screening performance is relevant to the HADS’ use as an outcome measure because it enables clinical meaning to be attached to differences or changes in scores. Outcomes on the HADS have been reported descriptively in some cases (e.g. means, standard deviations) and with reference to clinical cut-offs (e.g. percentage above and below) in others. To facilitate comparison between studies, future publications need to report results in both forms and use the same cut-offs. Cut-offs for the HADS-A and HADS-D recommended in the original article have been used most widely, namely: normal = 0–7, borderline = 8–10, clinical = 11–21 [50]. Further research is needed to confirm the optimal cut-off for the HADS-T.

POMS

The POMS-37 unofficial short-form scored highest after the HADS due to consistent evidence for its validity and responsiveness (weighted score = 60). The POMS-37 was developed specifically for use with cancer patients who may be too unwell to complete all original 65 items (POMS-65, weighted score = 55) [51]. It has correlated strongly with and matched the performance of the POMS-65 in three samples [51–53]. Unlike both the POMS-65 and HADS, the POMS-37 is free to use. All POMS versions differ from other PROMs reviewed here in that they have not been designed or used to screen for psychological disorders but rather to assess mood. However, the content and performance of the POMS-65 and 37 suggest these may have clinical utility yet to be explored. Items from the tension–anxiety and depression–dejection scales of both versions closely resemble DSM-IV-TR criteria, albeit with heavy emphasis on the cardinal features rather than across the gamut of symptoms. The depression–dejection scale of the POMS-65 has also correlated highly with the CES-D (0.63 [54]; 0.80 [55]), which, together with the SCL-90-R, offers the most comprehensive assessment of DSM criteria of PROMs reviewed here.

CES-D

The CES-D (weighted score = 55) has performed consistently well in screening and as an RCT outcome measure. However, its criterion validity has been evaluated in only two, small-scale studies focusing exclusively on major depression [34,56]; in one of these, its specificity was inferior to that of the HADS-T (see Table 10 above). Future studies are needed to evaluate the validity of items assessing problems with sleep, appetite and concentration in samples on active treatment. A further limitation of the CES-D concerns its somewhat “idiosyncratic” [1] assessment of symptom frequency rather than severity, leading to a mid-range rating regarding ease of administration and cognitive burden. The final feature that counted against the CES-D was the fact it requires 20 items to assess only one construct. Three short-forms of the CES-D have been developed, a 10-, an 11- and 15-item version. Neither the 10- nor 11-item versions have been validated in cancer patients, though the 11-item version performed satisfactorily in a sample of disease-free breast cancer survivors [57]. The 15-item version was developed using factor analysis after the two interpersonal items from the long-form were found uninformative and three further items were found to have an unacceptable gender bias in patients with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses and caregivers [58]. This version may show promise in the future.

Limitations

The current review focused on evidence for performance of PROMs in measuring anxiety, depression and distress in English-speaking adult patients receiving active treatment for heterogeneous cancers. The results should not be generalised to other linguistic or clinical contexts such as paediatric or palliative care.

Our review’s most important limitation concerns the potential for selection bias in identifying and reviewing evidence for each PROM. Limits on evidence for psychometric properties and PROM somatic content were imposed to maximise confidence when recommending use across cancer diagnoses and treatments. However, availability of published evidence is subject to a range of factors beyond PROM performance. PROMs may be used because they offer a ‘safe’ choice or potential for comparing with previous research rather than because they are suited to a particular study. This phenomenon introduced unavoidable bias to the review process. On the other hand, publication bias should not have posed a problem inasmuch as poorly performing PROMs can be expected to have presented a lower profile, consistent with the aims of the review. PROMs widely used in health settings but excluded because of a surprising lack of evidence for psychometric properties in English-speaking cancer populations were the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [59], Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) [60] and Beck Depression Inventory—Primary Care (BDI-PC) [61]. Item banks for administration via computer-adaptive testing are also becoming available for assessing anxiety and depression in cancer clinical research. Further research is needed to establish whether any of these alternatives offer advantages over the HADS, CES-D and POMS. Development of new, purpose-built PROMs aimed at addressing shortfalls in existing measures would be resource intensive and limit comparison between studies in and outside oncology.

Due to lack of precedent, decisions regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria were in some cases necessarily based on the authors’ expert opinion rather than on published evidence. Perhaps most important were our operational definitions of anxiety, depression and general distress, which excluded PROMs widely used in cancer research to assess coping, adjustment and PTSD. Readers are encouraged to critically appraise the relevance of these decisions within the context of the objectives and samples of each intended application. The weightings allocated to each property in our rating system could also be adapted to meet alternative requirements, although the fact that PROMs were ranked similarly by raw and weighted scores suggests the results are fairly robust.

A final limitation arose from the fact that only one RCT identified in Step 1 enabled head-to-head comparisons between candidate measures of the same construct [62]. More results of this type would have been valuable in distinguishing PROM performance from the influence of design and methodology, and future studies that compare PROMs are encouraged.

Recommendations

The HADS’ efficiency and substantial track record recommend its use where anxiety, mixed affective disorders or general distress are outcomes of interest. Where cost is a concern, the POMS-37 is recommended to measure anxiety or mixed affective disorders but does not offer a suitable index of general distress and, like the HADS, emphasises anhedonia in measuring depression. Where depression is the sole focus, the CES-D is recommended.

Further research is needed to inform interpretation of scores from the HADS-T and compare its performance with the HADS-D in assessing depressive disorders other than major depression. Evidence of this type has potential to inform not only outcome measurement but also screening in cancer clinics, which is becoming increasingly popular [63].

More generally, future studies are needed that directly compare PROMs of the same construct to assist researchers in choosing the most appropriate outcome measure for a given research context.

References

Love A. (2004). The identification of psychological distress in women with breast cancer. Sydney; available online at http://www.nbocc.org.au/resources/documents/IPD_The_identification_of_psychological_distress_in_women_with_breast_cancer.pdf: National Breast Cancer Centre.

Coyne JC, Lepore SJ, Palmer SC (2006) Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: evidence is weaker than it first looks. Ann Behav Med 32:104–110 [see comment][comment]

Gottlied BH, Wachala ED (2007) Cancer support groups: a critical review of empirical studies. Psycho-oncol 16:379–400

Graves KD (2003) Social cognitive theory and cancer patients' quality of life: a meta-analysis of psychosocial intervention components. Health Psychol 22:210–219

Lepore SJ, Coyne JC (2006) Psychological interventions for distress in cancer patients: a review of reviews. Ann Behav Med 32:85–92 [see comment]

Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M (2001) The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical review. Psycho-oncol 10:490–502

Owen JE, Klapow JC, Hicken B, Tucker DC (2001) Psychosocial interventions for cancer: review and analysis using a three-tiered outcomes model. Psycho-oncol 10:218–230

Rajasekaran M, Edmonds P, Higginson I (2005) Systematic review of hypnotherapy for treating symptoms in terminally ill adult cancer patients. Palliat Med 19:418–426

Redd WH, Montgomery GH, DuHamel KN (2001) Behavioral intervention for cancer treatment side effects. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:810–823

Rehse B, Pukrop R (2003) Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient educ couns 50:179–186

Roffe L, Schmidt K, Ernst E, Roffe L, Schmidt K, Ernst E (2005) A systematic review of guided imagery as an adjuvant cancer therapy. Psycho-oncol 14:607–617

Semple CJ, Sullivan K, Dunwoody L, Kernohan WG (2004) Psychosocial interventions for patients with head and neck cancer: past, present, and future. Cancer Nurs 27:434–441

Van Kuiken D (2004) A meta-analysis of the effect of guided imagery practice on outcomes. J Holist Nurs 22:164–179

Jacobsen PB, Jim HS (2008) Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: achievements and challenges. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 58:214–230

Rodin G, Lloyd N, Katz M, Green E, Mackay JA, Wong RKS et al (2007) The treatment of depression in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 15:123–136

Williams S, Dale J (2006) The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 94:372–390

Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M (2006) Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med 36:13–34

Uitterhoeve RJ, Vernooy M, Litjens M, Potting K, Bensing J, De Mulder P et al (2004) Psychosocial interventions for patients with advanced cancer—a systematic review of the literature. Br J Cancer 91:1050–1062

Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ (2002) Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:558–584

Love A (2004) The identification of psychological distress in women with breast cancer. The National Breast Cancer Centre.

Hersch J, Juraskova I, Price M, Mullen B (2009) Psychosocial interventions and quality of life in gynaecological cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 18:795–810

Smith JE, Richardson J, Hoffman C, Pilkington K (2005) Mindfulness-based stress reduction as supportive therapy in cancer care: systematic review. JAN Journal of Advanced Nursing 52:315–327

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2007). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Distress Management, from http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/distress.pdf

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth editionth edn. American Psychiatric, Washington DC, text revised (DSM-IV-TR)

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DLet al. (2006) Protocol of the COSMIN study: COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6: doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1186-1182.

Sansoni J, Marosszeky N, Jeon Y-H, Chenoweth L, Hawthorne G, King M et al (2007) Final report: dementia outcomes measurement suite project. University of Wollongong, Wollongong

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). (1999). The PEDro Scale. Retrieved 13th June 2009, from http://www.pedro.org.au/scale_item.html

King MT (1996) The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5:555–567

Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN, Friedlander M, Paris T (2010) Assessing health-related quality of life in gynecological oncology: a systematic review of questionnaires and their ability to detect clinically important differences and change. Int J Gynecol Cancer 20:664–684

King MT, Stockler MS, Cella D, Osoba D, Eton D, Thompson J et al (2010) Meta-analysis provides evidence-based effect sizes for a cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire, the FACT-G. J Clin Epidemiol 63:270–281

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Snaith RP, Zigmond AS (1994) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: manual. GL Assessment, London

Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T, Rudd N (2001) An analysis of the validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool in patients with advanced metastatic cancer. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 22:990–996

Katz MR, Kopek N, Waldron J, Devins GM, Tomlinson G (2004) Screening for depression in head and neck cancer. Psycho-oncol 13:269–280

Chaturvedi S (1991) Clinical irrelevance of HADS factor structure: comment. Br J Psychiatry 159:298

Smith AB, Wright EP, Rush R, Stark DP, Velikova G, Selby PJ (2006) Rasch analysis of the dimensional structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psycho-oncol 15:817–827

Le Fevre P, Devereux J, Smith S, Lawrie SM, Cornbleet M (1999) Screening for psychiatric illness in the palliative care inpatient setting: a comparison between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the General Health Questionnaire-12. Palliat Med 13:399–407

Pallant JF, Tennant A (2007) An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: an example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Br J Clin Psychol 46:1–18

Moorey S, Greer S, Watson M, Gorman C, Rowden L, Tunmore R et al (1991) The factor structure and factor stability of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with cancer. Br J Psychiatry 158:255–259 [see comment]

Johnston M, Pollard B, Hennessey P (2000) Construct validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale with clinical populations. J Psychosom Res 48:579–584

Rodgers J, Martin CR, Morse RC, Kendell K, Verrill M (2005) An investigation into the psychometric properties of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with breast cancer. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes 3:41

Smith AB, Selby PJ, Velikova G, Stark D, Wright EP, Gould A et al (2002) Factor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale from a large cancer population. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 75:165–176

Ibbotson T, Maguire P, Selby P, Priestman T, Wallace L (1994) Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer 30A:37–40

Osborne RH, Elsworth GR, Sprangers MAG, Oort FJ, Hopper JL (2004) The value of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for comparing women with early onset breast cancer with population-based reference women. Qual Life Res 13:91–206

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D, Bjelland I, Dahl AA et al (2002) The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52:69–77

0Hall A, A'Hern R, Fallowfield L (1999) Are we using appropriate self-report questionnaires for detecting anxiety and depression in women with early breast cancer? Eur J Cancer 35:79–85

Hopwood P, Howell A, Maguire P (1991) Screening for psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced breast cancer: validation of two self-report questionnaires. Br J Cancer 64:353–356

Ibbotson T, Maguire P, Selby P, Priestman T, Wallace L (1994) Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatment. Eur J Cancer 30:37–40

Mitchell AJ. (2009). How Accurate is the HADS as a screen for emotional complications of cancer? A metaanalysis against robust psychiatric interviews. Paper presented at the International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS) 11th World Congress, Vienna, Austria

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370

Shacham S (1983) A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess 47(3):305–306

DiLorenzo TA, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH, Valdimarsdottir H, Jacobsen PB (1999) The application of a shortened version of the Profile of Mood States in a sample of breast cancer chemotherapy patients. Br J Health Psychol 4:315–325

Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL (1995) Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): psychometric information. Psychol Assess 7:80–83

Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN (2002) A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-oncol 11:273–281

Conerly RC, Baker F, Dye J, Douglas CY, Zabora J (2002) Measuring depression in African American cancer survivors: the reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Study-Depression (CES-D) Scale. J Health Psychol 7:107–114

Hopko DR, Bell JL, Armento MEA, Robertson SMC, Hunt MK, Wolf NJ et al (2008) The phenomenology and screening of clinical depression in cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol 26:31–51

Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Sachs B et al (1998) Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs 19:481–494

Stommel M, Given BA, Given CW, Kalaian HA, Schulz R, McCorkle R (1993) Gender bias in the measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Psychiatry Res 49:239–250

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting psychologists, Palo Alto

Lovibond P, Lovibond S (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther 33(3):335–343

Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, Ball R (1997) Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav Res Ther 35:785–791

Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M (2000) A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med 62:613–622

Thomas BC, Bultz BD, Thomas BC, Bultz BD (2008) The future in psychosocial oncology: screening for emotional distress—the sixth vital sign. Future Oncol 4:779–784

McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF (1992) Manual for the Profile of Mood States (POMS): revised. Educational and Industrial Testing Service, San Diego

Center for Epidemiologic Studies (1971) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). National Institute of Mental Health, Rockville

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) BDI®-II Manual. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, Texas, USA

McNair DM, Heuchert JWP (2003) Profile of Mood States technical update. MHS, North Tonawanda, NY

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scale. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–1070

Derogatis LR et al (1974) SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale. Preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull 9:13–28

Veit CT, Ware JE (1983) The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 51:730–742

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N (1983) The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med 13(3):595–605

Derogatis LR, Rutigliano PJ (1996) Derogatis Affects Balance Scale (DABS). In: Spilker B (ed) Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials, 2nd edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC (1998) Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer 82:1904–1908

Hamilton M (1967) Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 6:278–296

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB (1999) Patient Health Questionnaire primary care study group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc 282:1737–1744

Cella DF, Jacobsen PB, Orav EJ, Holland JC, Silberfarb PM, Rafla S (1987) A brief POMS measure of distress for cancer patients. J Chron Dis 40:939–942

Leckie MS, Thompson E (1979) Symptoms of Stress Inventory. University of Washington Serial (Book, Monograph), Seattle

Carlson LE, Thomas BC (2007) Development of the Calgary Symptoms of Stress Inventory (C-SOSI). Int J Behav Med 14:249–256

Bradburn N (1969) The structure of psychological well-being. Aldine, Chicago

Beck AT, Steer RA (1990) Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1993) Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Goldberg D, Williams P (1988) A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ). GL Assessment, London

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL et al (1982) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17:37–49

Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE (1988) The MOS short-form General Health Survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 26:724

Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS et al (1993) How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol 65(2):375–390

Guadagnoli E, Mor V (1989) Measuring cancer patients' affect: revision and psychometric properties of the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1:150–154

Lorr M, McNair DM, Heuchert JWP (2003) Profile of Mood States Bi-polar supplement: POMS-Bi. MHS, North Tonawanda, NY

Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Koschera A, Naismith SL, Scott EM et al (2001) Development of a simple screening tool for common mental disorders in general practice. Med J Aust 175:10–17 [see comment]

Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, Penman D, Piasetsky S, Schmale AM et al (1983) The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 249:751–757

Fitch MI, Osoba D, Iscoe N, Szalai JP (1995) Predicting psychological distress in patients with cancer: conceptual basis and reliability evaluation of a self-report questionnaire. Anticancer Res 15:1533–1542

Zabora JR, Smith-Wilson R, Fetting JH, Enterline JP (1990) An efficient method for psychosocial screening of cancer patients. Psychosomatics 31:192–196

Payne DK, Hoffman RG, Theodoulou M, Dosik M, Massie MJ (1999) Screening for anxiety and depression in women with breast cancer. Psychiatry and medical oncology gear up for managed care. Psychosomatics 40:64–69

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen P, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C et al (2001) A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry 42(3):241–246

Hann D, Winter K, Jacobsen P (1999) Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). J Psychosom Res 46:437–443

Mitchell AJ (2007) Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders. J Clin Oncol 25:4670–4681 [see comment]

Gessler S, Low J, Daniells E, Williams R, Brough V, Tookman A et al (2008) Screening for distress in cancer patients: is the distress thermometer a valid measure in the UK and does it measure change over time? A prospective validation study. Psycho-oncol 17:538–547

Carroll BT, Kathol RG, Noyes R Jr, Wald TG, Clamon GH (1993) Screening for depression and anxiety in cancer patients using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 15:69–74

Sellick SM, Edwardson AD (2007) Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psycho-oncol 16(6):534–542

Walker J, Postma K, McHugh GS, Rush R, Coyle B, Strong V et al (2007) Performance of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool for major depressive disorder in cancer patients. J Psychosom Res 63:83–91

Cull A, Gould A, House A, Smith A, Strong V, Velikova G et al (2001) Validating automated screening for psychological distress by means of computer touchscreens for use in routine oncology practice. Br J Cancer 85:1842–1849

Love AW, Kissane DW, Bloch S, Clarke D (2002) Diagnostic efficiency of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in women with early stage breast cancer. Aust N Z j psychiatry 36:246–250

Love AW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, Bloch S, Kissane DW (2004) Screening for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer: a comparison of the Beck Depression Inventory Short Form and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Aust N Z j psychiatry 38:526–531

Janda M, Obermair A, Cella D, Perrin LC, Nicklin JL, Ward BG et al (2005) The Functional Assessment of Cancer—Vulvar: reliability and validity. Gynecol Oncol 97:568–575

Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Ding B, Malin J, Peterman A, Calhoun E et al (2008) Measuring health-related quality of life and neutropenia-specific concerns among older adults undergoing chemotherapy: validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Neutropenia (FACT-N). Support Care Cancer 16:47–56

Boyes A, Girgis A, Zucca A, Lecathelinais C (2009) Anxiety and depression among long-term survivors of cancer in Australia: results of a population-based survey. Med J Aust 190:S94–S98

Manne S, Schnoll R (2001) Measuring cancer patients' psychological distress and well-being: a factor analytic assessment of the Mental Health Inventory. Psychol Assess 13:99–109

Clover K, Carter GL, Adams C, Hickie I, Davenport T (2009) Concurrent validity of the PSYCH-6, a very short scale for detecting anxiety and depression, among oncology outpatients. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 43:682–688

Cole BS (2005) Spiritually-focused psychotherapy for people diagnosed with cancer: A pilot outcome study. Ment health Relig Cult 8:217–226

Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Sela RA, Quinney HA, Rhodes RE, Handman M et al (2003) The group psychotherapy and home-based physical exercise (group-hope) trial in cancer survivors: physical fitness and quality of life outcomes. Psycho-oncol 12:357–374

Doorenbos A, Given B, Given C, Verbitsky N, Cimprich B, McCorkle R et al (2005) Reducing symptom limitations: a cognitive behavioral intervention randomized trial. Psycho-oncol 14:574–584

Downe-Wamboldt BL, Butler LJ, Melanson PM, Coulter LA, Singleton JF, Keefe JM et al (2007) The effects and expense of augmenting usual cancer clinic care with telephone problem-solving counseling. Cancer Nurs 30:441–453

Badger T, Segrin C, Meek P, Lopez AM, Bonham E, Sieger A et al (2005) Telephone interpersonal counseling with women with breast cancer: symptom management and quality of life. Oncology Nursing Forum Online 32:273–279

Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, Meek P, Lopez AM. (2007). Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nursing Research 56(1):44–53

Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, Meyerowitz BE, Bower JE, Krupnick JL et al (2005) Outcomes from the Moving Beyond Cancer psychoeducational, randomized, controlled trial with breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 23:6009–6018

Steel JL, Nadeau K, Olek M, Carr BI (2007) Preliminary results of an individually tailored psychosocial intervention for patients with advanced hepatobiliary carcinoma. J Psychosoc Oncol 25:19–42

Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, Rodriguez MA, Chaoul-Reich A (2004) Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer 100:2253–2260

Wilkinson SM, Love SB, Westcombe AM, Gambles MA, Burgess CC, Cargill A et al (2007) Effectiveness of aromatherapy massage in the management of anxiety and depression in patients with cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 25:532–539

Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, Roberts H, Koopman C, Adams RE et al (2003) Evaluation of an internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer 97:1164–1173

Krischer MM, Xu P, Meade CD, Jacobsen PB, Krischer MM, Xu P et al (2007) Self-administered stress management training in patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25:4657–4662

Carmack Taylor CL, Demoor C, Smith MA, Dunn AL, Basen-Engquist K, Nielsen I et al (2006) Active for life after cancer: a randomized trial examining a lifestyle physical activity program for prostate cancer patients. Psycho-oncol 15:847–862

Dirksen SR, Epstein DR, Dirksen SR, Epstein DR (2008) Efficacy of an insomnia intervention on fatigue, mood and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs 61:664–675

Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, Rawl S, Monahan P, Burns D et al (2005) Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: a randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer 104:752–762

Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM (2004) Development and pilot testing of a psychoeducational intervention for oral cancer patients. Psycho-oncol 13:642–653

McCorkle R, Dowd M, Ercolano E, Schulman-Green D, Williams AL, Siefert ML et al (2009) Effects of a nursing intervention on quality of life outcomes in post-surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psycho-oncol 18:62–70

Lepore SJ, Helgeson VS, Eton DT, Schulz R (2003) Improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial of group education interventions. Health Psychol 22:443–452

Orringer JS, Fendrick AM, Trask PC, Bichakjian CK, Schwartz JL, Wang TS et al (2005) The effects of a professionally produced videotape on education and anxiety/distress levels for patients with newly diagnosed melanoma: a randomized, prospective clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:224–229

Kissane DW, Bloch S, Smith GC, Miach P, Clarke DM, Ikin J et al (2003) Cognitive-existential group psychotherapy for women with primary breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Psycho-oncol 12:532–546

Boyes A, Newell S, Girgis A, McElduff P, Sanson-Fisher R (2006) Does routine assessment and real-time feedback improve cancer patients' psychosocial well-being? Eur J Cancer Care 15:163–171

Kornblith AB, Dowell JM, Herndon JE, Engelman BJ, Bauer-Wu S, Small EJ et al (2006) Telephone monitoring of distress in patients aged 65 years or older with advanced stage cancer: a cancer and leukemia group B study. Cancer 107:2706–2714, 2nd

Schofield P, Payne S. (2003). A pilot study into the use of a multisensory environment (Snoezelen) within a palliative day-care setting. International journal of palliative nursing 9(3):124–130

Espie CA, Fleming L, Cassidy J, Samuel L, Taylor LM, White CA et al (2008) Randomized controlled clinical effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy compared with treatment as usual for persistent insomnia in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 26:4651–4658

Pitceathly C, Maguire P, Fletcher I, Parle M, Tomenson B, Creed F (2009) Can a brief psychological intervention prevent anxiety or depressive disorders in cancer patients? A randomised controlled trial. Ann Oncol 20:928–934

Savard J, Simard S, Giguere I, Ivers H, Morin CM, Maunsell E et al (2006) Randomized clinical trial on cognitive therapy for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer: psychological and immunological effects. Palliat Support Care 4:219–237

Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, Rush R, Postma K, Tulloh A et al (2004) Major depression in outpatients attending a regional cancer centre: screening and unmet treatment needs. Br J Cancer 90:314–320

Clark M, Isaacks-Downton G, Wells N, Redlin-Frazier S, Eck C, Hepworth JT et al (2006) Use of preferred music to reduce emotional distress and symptom activity during radiation therapy. J Music Ther 43:247–265

Hanser SB, Bauer-Wu S, Kubicek L, Healey M, Manola J, Hernandez M et al (2006) Effects of a music therapy intervention on quality of life and distress in women with metastatic breast cancer. Journal Of The Society For Integrative Oncology 4:116–124

Allen SM, Shah AC, Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Ciambrone D, Hogan J et al (2002) A problem-solving approach to stress reduction among younger women with breast carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 94:3089–3100

Rosenbloom SK, David E, Victorson DE, Hahn EA, Peterman AH, Cella D (2007) Assessment is not enough: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of HRQL assessment on quality of life and satisfaction in oncology clinical practice. Psycho-oncol 16:1069–1079

Edmonds CVI, Lockwood GA, Cunningham AJ (1999) Psychological response to long term group therapy: a randomized trial with metastatic breast cancer patients. Psycho-oncol 8:74–91

Bailey DE, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Mohler J, Bailey DE et al (2004) Uncertainty intervention for watchful waiting in prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs 27:339–346

Lemieux J, Beaton DE, Hogg-Johnson S, Bordeleau LJ, Hunter J, Goodwin PJ (2007) Responsiveness to change to change due to supportive-expressive group therapy, improvement in mood and disease progression in women with metastatic breast cancer. Qual Life Res 16:1007–1017

Lemieux J, Beaton DE, Hogg-Johnson S, Bordeleau LJ, Goodwin PJ (2007) Three methods for minimally important difference: no relationship was found with the net proportion of patients improving. J Clin Epidemiol 60:448–455

Powell CB, Kneier A, Chen LM, Rubin M, Kronewetter C, Levine E et al (2008) A randomized study of the effectiveness of a brief psychosocial intervention for women attending a gynecologic cancer clinic. Gynecol Oncol 111:137–143

Sandgren AK, McCaul KD (2003) Short-term effects of telephone therapy for breast cancer patients. Health Psychol 22:310–315

Sandgren AK, McCaul KD, Sandgren AK, McCaul KD (2007) Long-term telephone therapy outcomes for breast cancer patients. Psycho-oncol 16:38–47

Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately-Aldous S (2006) A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psycho-oncol 15:891–897

Levine EG, Eckhardt J, Targ E (2005) Change in post-traumatic stress symptoms following psychosocial treatment for breast cancer. Psycho-oncol 14:618–635

Pinto BM, Clark MM, Maruyama NC, Feder SI, Pinto BM, Clark MM et al (2003) Psychological and fitness changes associated with exercise participation among women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncol 12:118–126

Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Murray G, Wall L, Walker J et al (2008) Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet 372:40–48 [see comment]

Monti DA, Peterson C, Kunkel EJ, Hauck WW, Pequignot E, Rhodes L et al (2006) A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psycho-oncol 15:363–373

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest relating to this manuscript.

No Ethics approval was required to conduct the systematic review or analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luckett, T., Butow, P.N., King, M.T. et al. A review and recommendations for optimal outcome measures of anxiety, depression and general distress in studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for English-speaking adults with heterogeneous cancer diagnoses. Support Care Cancer 18, 1241–1262 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0932-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0932-8