Abstract

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) is an autotetraploid, allogamous and heterozygous species whose cultivars are synthetic populations. The breeders apply selection pressure for some agronomic traits within a breeding pool to increase the frequency of favorable individuals. The objective of this study was to investigate the differentiation level among seven cultivars originating from one breeding program, and between these cultivars and the breeding pool, with eight SSR markers. These highly polymorphic and codominant markers, together with recent population genetic statistics extended to autotetraploids, offer tools to analyse genetic diversity in alfalfa. The number of alleles per locus varied between 3 and 24. All loci were at a panmictic equilibrium in the cultivars, except one, probably because of null alleles. With seven SSR loci, each cultivar was at panmictic equilibrium. The mean gene diversity was high, ranging from 0.665 to 0.717 in the cultivars. The parameter F ST indicated a low but significant diversity among cultivars. Among 21 pairs of cultivars, 15 were significantly different. The breeding pool also had a high diversity, and was significantly different from each cultivar except the most recent one. Considering the characteristics of the breeding program and the mode of cultivar elaboration, we found that they were unable to generate a large variety differentiation. Estimation of population genetics parameters at SSR loci can be applied for assessing the differences between cultivars or populations, either for variety distinction or the management of genetic resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is the most cultivated forage legume, with about 32 million hectares over the world (Michaud et al. 1988). Its agronomical interest is based on its high protein content, suitable feeding value and favorable environmental impact (perenniality and no nitrogen fertilizer required). It is an autotetraploid (Stanford 1951), with 2n = 4x = 32 (Armstrong 1954; Demarly 1954), allogamous and seed-propagated species. These factors contribute to the genetic complexity of alfalfa at both individual and population levels.

Cultivated varieties are synthetic cultivars, usually obtained through three or four generations of panmictic reproduction of a set of various numbers of parents. The parents can be clones, half-sib or full-sib families. Breeding programs mainly focus on pest or disease resistance, lodging resistance and forage quality, that must be achieved within an adapted autumn dormancy range (to avoid winter killing), and with a high forage yield (Irwin et al. 2001; Lonnet 1996; Volenec et al. 2002). Selection after inbreeding phases is avoided or limited because of pronounced inbreeding depression. The breeders maintain a breeding pool, from which they extract families or plants for variety creation. After several cycles of selection, it is difficult to know if the original genetic diversity present in the breeding pool was maintained, increased through introductions or decreased through intense selection. The successive cultivars released from a breeding program, even if genetically related, are supposed to be different for at least one trait of agronomic interest. A retrospective analysis of a breeding scheme could help in taking appropriate decisions in the management of breeding programs. Since neutral markers are expected to reflect the demographic and (neutral) genetic history of the populations, analyzing the genetic diversity present for molecular markers in the different breeding products should help to determine the main factors (genetic drift, subdivision, etc.,) at work in a breeding scheme.

The use of SSR loci as polymorphic DNA markers has expanded considerably over the past decade both in the number of studies and in the number of organisms, primarily due to their facility and power for population genetic analyses (Estoup and Angers 1998). To date, few studies have been conducted using SSR markers to assess the level of variation among perennial Medicago species and populations. Diwan et al. (1997) have been the first to develop SSR markers in Medicago. They have shown how SSR can be used to describe genetic diversity and to analyze the genetic relationships among genotypes in alfalfa. Mengoni et al. (2000) have verified the power of chloroplastic SSR for the detection of polymorphism in cultivated alfalfa populations. Recently, a set of 107 SSRs identified in the EST database of Medicago truncatula was mapped in M. sativa (Julier et al. 2003) and can be used to perform genetic diversity analysis. Among these markers, some were easy to score with allele doses, i.e. with tetraploid genotypic information.

Some of the most useful measures of population structure are the F-statistics (Wright 1951). F-statistics can be thought of as a measure of the correlation of alleles within individuals or populations and are related to inbreeding coefficients. An inbreeding coefficient is a measure of the non-random association of alleles within an individual. As such, F-statistics describe the amount of inbreeding-like effects within subpopulations (F IS), among subpopulations (F ST), and within the entire population (F IT). A theoretical framework for the analysis of population structure in autotetraploid species is available (Ronfort et al. 1998). In contrast to diploids, the correlation of genes between individuals within-population with respect to genes between populations (F ST) may vary among loci due to double reduction and may be consequently inappropriate for estimating demographic parameters in autotetraploid populations. Ronfort et al. defined a new parameter (ρ) more appropriate to analyze population structure in autotetraploids, because its relationship with the migration rate and the population size was shown to be independent from both the selfing rate and the proportion of double reduction. A single study (Jenczewski et al. 1999) used F ST and ρ in tetraploid species. In the other studies based on codominant markers, diversity parameters in tetraploid species were evaluated without scoring the allele doses and without taking into account the full genotypic information: each allele, or band, obtained from a codominant locus was treated as a dominant marker with two positions: presence and absence.

The objective of this study was to investigate the level of differentiation among a set of cultivars originating from a single breeding program, and between these cultivars and the breeding pool. A progressive loss of genetic variability was feared by the breeder, due to both selection and genetic drift. We tried to use the codominant SSR markers available in M. sativa and the population structure parameters (F-statistics) applied to autotetraploid species to address these questions in alfalfa.

Materials and methods

Plant material

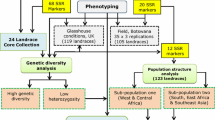

We focused on the varieties and the breeding pool of a French private breeder (GIE GRASS, formerly GIE Verneuil). The breeding pool was originally created in the 1960s from Flemish landraces. A family selection is applied for forage yield, disease, pest and lodging resistance, protein content and seed yield. Populations of various origins (USA, Turkey, registered varieties from Europe) are introduced each year, but a low proportion of them is selected for the next generation. Seven Flemish cultivars were analyzed: six were registered on the French official list and one is under registration (Table 1). For all varieties, the parents are half-sib families (Fig. 1) conserved as seeds. In the first synthetic generation, 40 plants representing each parent are planted in a polycross. The fourth synthetic generation is the commercial one. Official registration trials indicated that (i) Diane, Harpe, Kali and Timbale were more resistant to nematode (Ditylenchus dipsacii) than the control cultivar Europe, (ii) Julia and Rachel were improved for protein content, and (iii) all cultivars had a high resistance level to Verticillium alboatrum (GEVES 1993; GEVES 2001). Finally, L1460 has a very high level of nematode resistance (unpublished result). In our experiment, each cultivar was represented by 20 plants, except Harpe that was represented by 40 plants. The breeding pool was represented by 49 plants, each taken in one half-sib family in the breeder’s nursery planted in 2003. These 209 plants were used for SSR analysis. Young leaflets were harvested and DNA was extracted following the method described by Cheung et al. (1993).

Simple sequence repeat marker analysis

Eight SSR primer pairs, each of which amplified a single locus, and originated from M.truncatula were chosen based on their position on the genetic linkage map, in order to have one marker on each chromosome (Julier et al. 2003). Preliminary tests (data not shown) were performed on a few plants. The parents of a mapping population, for which genetic studies have shown the dose of each allele (Julier et al. 2003) were added as controls. We chose polymorphic markers with an easy-to-score profile (no ladder profile) and for which we were able to correctly score the dose of each allele (Table 2). SSR markers with a high number of alleles in the parents and in the individuals of the preliminary tests were preferred in order to avoid null alleles. For each marker, an optimal dilution of PCR products was defined: band intensity should not be saturated to determine the dose of each allele.

Each locus was amplified by PCR and fluorescently labeled by an M13 tailing scheme (Boutin-Ganache et al. 2001), where the forward primer was 5′ tailed with the M13 forward sequence and used in conjunction with a fluorescently labeled M13 forward primer. The PCR reactions were performed in a PTC100 thermocycler (MJ Research Inc.). A denaturation period of 4 min at 94°C was followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at Tm (Table 2) and 1 min at 72°C, and then 10 min at 72°C for final extension. Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 20 μl containing 1Xbuffer, 0.2 mM each of dNTP, 0.4 μM of SSR primers (forward, reverse and fluorescently labeled M13 forward primers), 1.5 mM of MgCl2, 2 μl of genomic DNA diluted at 1/20 (approximately 35 ng) and 0.6 units of Platinium Taq Polymerase (Invitrogen Inc.). The PCR products were denaturated and separated in 6.5% polyacrylamide denaturing gels (Li-COR Inc.) using an automated DNA sequencer LI-COR IR2 (LI-COR Inc.).

Images of gels (Fig. 2) were treated in two steps with GENE PROFILER software (Scanalytics, Inc.). In the first step, the different alleles were identified. Some bands, that were always present together with another band were considered as “replicates” and discarded. In the second step, for each individual (i.e. within each lane), the number of different alleles was determined. Allele dose were scored assuming the absence of null alleles. Light intensity and contrast were tuned, and density profiles were used to clearly score each individual. When an individual showed four alleles, each had a single dose. If it had a single allele, this allele was in four doses. If an individual had three alleles, the allele with the highest intensity was considered to be in double dose, whereas the other alleles were in single dose. In an individual had two alleles, the dose of each allele could be one, two or three. If one allele was more intense that the other, it was considered as triple dose; if both bands were of equal intensity, they were scored with double dose. The raw gel data were extracted as a database using GENE PROFILER software and exported as allele sizes for further formatting as input files for statistical analysis.

Example of SSR variation at MAA660456 locus on 38 individuals. In this locus, each allele is represented by a double band. Black arrows indicate the different alleles. White arrows show “replicate” bands that were discarded. Within each lane, the dose of each allele was scored depending on its intensity. The dose was indicated by close ticks. For example, individual in lane 1 had four alleles, each in single dose; individual in lane 4 had three alleles, in doses 2/1/1 from the bottom; individual in lane 12 had two alleles, the lowest in triple dose and the highest in single dose; individual in lane 24 had two alleles, each in double dose

Statistical analysis of SSR data

The within-population genetic diversity was estimated as the number of alleles (A) and the expected heterozygosities according to Hardy–Weinberg expectations (H E ) for each microsatellite locus. To allow comparisons between populations, the number of alleles per locus for Harpe and for the breeding pool was calculated using the rarefaction method as described in Petit et al. (1998) for a sample size of 20 individuals. Expected heterozygosities (Nei 1973) were calculated as (1-∑pi 2)*4 n/(4 n-1) where pi is the frequency of the ith allele and n the number of individuals in the sample as recommended for autotetraploid species (Thrall and Young 2000). H E was estimated assuming random chromosome segregation (i.e. random assortment of homologous chromosomes into gametes), as random chromatid segregation, known as double reduction, is infrequent in alfalfa (Julier et al. 2003). To compare the genetic diversity observed in each cultivar with the genetic diversity present in the breeding pool, we performed Wilcoxon’s Signed-ranks test for pairwise comparisons on both H E and A.

To test for a departure from Hardy–Weinberg expectations in the different studied populations, we used the software AUTOTET (Thrall and Young 2000). This software computes a fixation coefficient (F) as F=1-(H0 /H E ), with H0 the observed heterozygosity. F corresponds to the parameter F IS classically used in diploids to measure departure from Hardy–Weinberg expectations. For autotetraploids, H0 can be calculated weighting each genotype by the proportion of heterozygous gametes this genotype should produce (for e.g. heterozygotes iijj, iiij and iijk have H values of 2/3, 1/2 and 5/6 respectively, see Bever and Felber 1992). AUTOTET also computes a “Goodness of fit” test that compares the observed genotype frequencies to that expected under random chromosomal segregation and random mating within-population for each locus and each population. To assess departure from Hardy–Weinberg expectations within-population, we applied Bonferroni corrections over the different loci analyzed, adjusting P-values experimentally for a testwise P-value of 0.05.

No null homozygote was observed in our data (i.e. a PCR product was obtained from all individuals), suggesting that putative null alleles occurred at very low frequencies. Nevertheless, in order to assess whether departure from equilibrium could be an artifact due to the presence of null alleles, the frequencies of putative null alleles were estimated from the heterozygote deficiency following Brookfield (1996) as r = (H E -H0)/(1+ H E ) for each locus and each population. This method assumes that the population is at Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

The level of differentiation between the different cultivars was measured using the two differentiation parameters, F ST and ρ (Ronfort et al. 1998). Computation of these parameters follows an ANOVA framework (Weir and Cockerham 1984) extended to autotetraploid species and was achieved using the software Gene4X (Ronfort et al. 1998). Differentiation significance was checked through Fischer’s Exact tests expanded to autotetraploids (Raymond and Rousset 1995). To verify the accuracy of the sample size (20 plants per cultivar), we used data from the cultivar Harpe for which 40 plants (instead of 20) were analyzed. A hundred samples of 20 plants were built through random sampling in 40 individuals. We computed F ST between each of these samples and the other cultivars and analysed the distribution of F ST and its significance.

The SSR data set on two cultivars, Diane and Harpe, was used to evaluate linkage disequilibrium between loci. Such disequilibrium could only originate from the history of each cultivar or of the breeding selection, as the loci were mapped on separate chromosomes. No software is available to measure linkage disequilibrium in autotetraploids, and the large number of alleles per locus makes very difficult a global analysis. So for each locus, the most frequent allele was chosen. Considering two loci, a 2×2 contingency table was constructed with the number of plants in each combination of genotypes (presence or absence of the allele). A Fisher Exact test was performed on each contingency table.

Results

Genetic diversity

The gels obtained with each of the eight microsatellite loci (see Fig. 2) were read taking into account the allele doses. A total of 119 alleles was detected in a set of seven commercial cultivars and the breeding pool of a single breeder (Table 3). The number of alleles per locus ranged from 3 for MTIC93 to 24 for MTIC432 with an average of 14.9 alleles per locus. The number of alleles tended to be higher in the breeding pool, but this tendency was not true after correction of the allelic richness for sample size (Table 3). Most of the alleles present in at least one cultivar were also present in the breeding pool. After correction for the sample size (rarefaction method (Petit et al. 1998)), the genetic diversity measured as the number of alleles per population was not significantly different in the breeding pool compared to the different cultivars (Wilcoxon’s Signed rank test). The mean number of alleles per plant (A) per locus ranged from 1.92 for MTIC299 to 3.25 for MTIC189. For all SSR loci (Fig. 3), the most frequent and unfrequent alleles were the same among all the cultivars and the breeding pool whatever the number of alleles per locus.

One SSR locus, MTIC299, showed a significant heterozygote deficiency in all cultivars except L1460, with F-values ranging from 0.233 to 0.456 (P< 0.001). The excess of homozygotes for MTIC299 may be due to the presence of null alleles, so we estimated the null allele frequency (Brookfield 1996). In each cultivar, the frequency of null alleles was high for the locus MTIC299, ranging from 0.092 to 0.192. It was low for the other loci in each cultivar, the estimates ranging from −0.038 to 0.047. Given these large frequencies of null alleles for MTIC299, this locus was removed from the data for the following analyses. For the other loci, F ranged from −009 to 0.19. Applying a threshold level with a correction of Bonferroni, we found a deviation from random mating equilibrium on rare occasions: MTIC93 in Timbale, FMT13 in Julia, MAA660456 in L1460 and Harpe, MTIC189 and B14B03 in the breeding pool. Globally, all the studied cultivars and the breeding pool showed no departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

The mean genetic diversity (H e) for each cultivar and for the breeding pool, calculated without MTIC299, ranged from 0.665 to 0.717, indicating high within-population variability (Table 4). A Wilcoxon’s Signed rank test performed between each cultivar and the breeding pool on H e showed that the genetic diversity in the breeding pool is not significantly different from that of the cultivars (P< 0.05). Finally, H e was not related to the year of registration nor to the number of parents of the cultivars.

Population differentiation

The F ST and ρ estimators of genetic differentiation were first calculated on the seven cultivars and the breeding pool for each locus separately (except MTIC299 that was discarded). Estimates were low, but significant (Table 5). Overall, for loci and all populations, F ST was highly significant (P<0.001).

We also calculated the differentiation between each pair of cultivars (Table 6). On 21 pairs of cultivars only 6 were not significantly differentiated. Julia was the cultivar that differed the least from the other cultivars while Diane was significantly differentiated from all the other cultivars. The differentiation (F ST) between the breeding pool and the cultivars ranged from 0 (P>0.05) to 0.005 (P<0.001). Interestingly, the two oldest cultivars had the highest F ST with the breeding pool, and the most recent cultivar the lowest one.

When Harpe was represented by 40 plants, the differentiation (F ST) between Harpe and Diane was highly significant (0.008, P<0.001) whereas it was not significant between Harpe and Timbale (0.005, P>0.05). The F ST values obtained between 100 samples of 20 plants of Harpe and Diane ranged between 0.002 and 0.012, 99% of them being significant. Between Harpe and Timbale, F ST ranged from −0.003 to 0.013, 9% of them being significant.

Linkage disequilibrium

Linkage disequilibrium was tested in two cultivars, Diane and Harpe. In both cultivars, no pair of markers showed significant linkage disequilibrium, with P-values ranging from 0.20 to 1.

Discussion

The SSR loci, with a scoring of the allelic doses, gave us the possibility to exploit the whole genotypic information. The allele frequencies were also calculated with a dominant scoring of the alleles (not shown). The frequencies of the rare alleles were then higher, and the frequencies of frequent alleles were lower than in the codominant scoring. This result confirms the reliability of codominant scoring for this set of SSR markers. We used these codominant markers to evaluate the genetic diversity in a set of cultivars registered during the last two decades by a single breeder. To date, in all population analyses on tetraploid alfalfa with codominant markers except one (Jenczewski et al. 1999), the genotypic information was reduced to an allelic information, using binary code (0/1) for their presence or absence (Labombarda et al. 2000; Maureira et al. 2004; Mengoni et al. 2001; Morales Corts and Crespo Martinez 2000; Pupilli et al. 1996; Pupilli et al. 2000; Riday et al. 2003; Valizadeh et al. 1996).

A large number of alleles was revealed, as previously observed in alfalfa for SSR markers (Diwan et al. 1997; Mengoni et al. 2000; Riday et al. 2003). The number of alleles per locus was approximately the same for each cultivar and for the breeding pool. In our study, a few cultivar-specific alleles were found and their frequencies were less than 10%. The detection of such rare alleles was just related to sampling effects. In addition, when we observed the allelic frequencies per locus, we noted that the most frequent and unfrequent alleles were the same among all commercial cultivars and the breeding pool. This observation was further confirmed by the low level of differentiation measured among the set of populations studied.

The within-population diversity, measured by the mean number of alleles per plant (A) and the mean genetic diversity (H E ), was high for each cultivar and for the breeding pool, as found in a range of diverse populations of alfalfa, cultivated or wild, of various origins (Brummer et al. 1991; Crochemore et al. 1996; Ghérardi et al. 1998; Jenczewski et al. 1999; Labombarda et al. 2000; Mengoni et al. 2000; Morales Corts and Crespo Martinez 2000; Pupilli et al. 1996; Pupilli et al. 2000). However, Jenczewski et al. (1999) found lower levels of gene diversity (from 0.163 to 0.347) in a set of both wild and cultivated populations. This result is in accordance with the classical view that microsatellite markers are associated with larger mutation rate than most other genetic markers (Jarne and Lagoda 1996).

Mean gene diversity was not related to the number of parents of the cultivars nor to their year of registration. In this set of cultivars coming from a single breeding program, with the parents of the cultivars being half-sib families represented by 40 plants, it is easy to calculate that a cultivar contained 160 x alleles, x being the number of selected female parents (Fig. 1). Half of these alleles come from the female parents and half from the pollen of the 500 plants selected among the whole breeding pool (usually represented by about 8000 plants in the nursery). The first half of alleles can show some modifications of the allele frequencies compared to the breeding pool, just because of plant sampling. The second half of alleles is more or less the same for all cultivars, except if the breeding pool derived with time. This scheme of sampling has been modeled for diploids (Crossa and Vencovsky 1997) to allow the computation of the corresponding variance effective population size (N e(v)). Using this formula, N e(v) ranged from 11 to 57 depending on the number of parental female plants of the variety (3 to 15). These values are probably underestimates of the effective population size of the studied populations due to their autotetraploid status. Indeed, autopolyploidy is expected to double the effective population size compared to diploids because each individual bears four alleles per locus instead of two in diploids (Bever and Felber 1992; Moody et al. 1993). Considering that F ST can be expressed as a function of N e(v) : F ST = 1/(4 N e(v)) (Moody et al. 1993) and the value of N e(v) computed above, we expect F ST between an alfalfa cultivar and the breeding pool to vary between 0.004 and 0.022 (if N e(v) are underestimated, then these F ST values are overestimated). Our calculated F ST between the breeding pool and each cultivar were close to the lowest of these estimates and generally lower. As the mean diversity did not decrease with the year of registration, it is hoped that the genetic diversity was maintained in the breeding pool. This means that the way the breeding pool is managed (regular introduction of new material, maintenance of an average level of production through selection...) results in an effective population size large enough to prevent genetic drift. Our results also show that the sampling effect due to the selection within the breeding pool of the female parental plants has a reduced impact on the differentiation between each cultivar and the breeding pool. Finally, this breeding procedure produces cultivars with small differences in allelic frequencies, which means that the sampling process in the breeding pool has only a small effect (no bottleneck effect). Cultivars coming from different breeding programs could be substantially more different on the basis of neutral markers. Nevertheless, in a set of cultivars of diverse origins, similar allelic frequencies were also observed for isozymic loci among cultivars (Morales Corts and Crespo Martinez 2000).

Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was assessed at each locus for each population. A significant deficiency of heterozygotes was found for the locus MTIC299. As a single locus was concerned, this deviation is probably due to the occurrence of null alleles at this locus, a result consistent with its low number of alleles per plant (1.92). The occurrence of null (non-amplifying) alleles can be the result of divergence in the sequences flanking the microsatellite, undetectable on the unqualified DNA template. Thus it causes heterozygotes to be mis-scored as homozygotes. Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was assessed within each population (cultivars and breeding pool) for all the other loci. All the cultivars were in equilibrium, as expected from their production through three or four generations of panmictic multiplication in polycross (Gallais 2003). The breeding pool showed no significant departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Microsatellite data, obtained with seven loci, indicated a low but significant genetic differentiation in overall cultivars when submitted to powerful statistical procedures such as the F-statistics. F ST values showed that the subdivision of the whole data set in a set of eight populations explained less than 1% of the total variation. Similarly Labombarda et al. (2000) and Pupilli et al. (2000) found that within-cultivar variation explained 98 to 99% of total variation observed in two Italian cultivars with RFLP markers. In a set of 12 wild and cultivated M. sativa populations from Spain, Jenczewski et al. (1999) found an F ST of 0.0490 with isozymes. This value is higher than our result, but the studied populations covered a much wider geographic and genetic origin. The F ST estimate was negative for one marker (B14B03), as it can be observed when the true F ST value is close to 0 (Weir 1996). The pairwise analysis of cultivars allowed distinguishing 15 pairs of cultivars out of 21. As discussed above, the fact that all the cultivars were produced in the same breeding program is probably responsible for this low differentiation. However, registration on the French list includes a step of evaluation of distinctness against all already registered cultivars, based on morphological traits. Each cultivar studied here passed this test, except the most recent one (L1460), which means that all the cultivars are different from one another for morphological or agronomical characteristics. The most recent cultivar, L1460 and the breeding pool collected in 2003 were not significantly different. This feature could indicate that a cultivar is a sample of the breeding pool when considering neutral markers, and that a slow shift in the breeding pool probably occurs during selection, slightly modifying allelic frequencies. The agronomic evaluation of the cultivars, showing significant progress for pest or disease resistance and protein content, indicates that this progress was obtained without strong modification of the breeding pool for neutral markers. Recently, new Bayesian approaches have been developed to study population structure (Falush et al. 2003; Pritchard et al. 2000). They are useful to assign individuals to populations. In the present context, these methods would have had difficulties in giving a structuration to the overall population.

Analysed within two different cultivars, linkage disequilibrium seems to be not significant between pairs of markers. The markers are mapped on different chromosomes, so they are genetically independent. Even if their history is very specific (selection followed by generations of intermating), the cultivars could be used in further association studies, aimed at finding a relationship between allelic and phenotypic variations.

In the present study, each cultivar was represented by 20 plants (80 alleles), except one – Harpe–that was represented by 40 plants (160 alleles). A large sample of plants is more adapted to catch rare alleles and to evaluate their frequency than a small sample. Resamplings of 20-plant samples in Harpe gave the same among-cultivar differentiation (F ST). Similarly, Labombarda et al. (2000) showed that the sampling of 20 plants is enough to assess genetic variation among cultivars using codominant markers. Indeed the reliability of estimates for genetic variation, such as gene diversity, F ST and genetic distances, depends more on the number of loci than on the number of individuals (Bataillon et al. 1996; Nei and Roychoudhury 1974). Among the eight SSR loci, seven were used, and gave a picture of the genetic structure. More loci could only help to precise the F ST values. As a comparison, ten randomly selected SSR loci were found sufficient to uniquely fingerprint 260 maize inbred lines representing the diversity used in breeding (Liu et al. 2003).

Although the analyses of genetic diversity with SSR markers are numerous in plants, the studies in allogamous species with synthetic varieties or populations are scarce. On alfalfa, with RFLP and SSR markers, a differentiation was found between the sub-species sativa and falcata, but the level of differentiation was low among three cultivars coming from three different breeders (Maureira et al. 2004). Similarly, a set of nine SSR markers were unable to differentiate among three populations of tetraploid birch (Betula pubescens) (Truong et al. 2004). But on diploid perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), the seven studied cultivars could be distinguished using a set of 22 SSR markers (Kubik et al. 2001).

The results obtained here showed the possibility of genetic diversity analysis of tetraploid alfalfa populations, based on codominant SSR markers treated with F-statistics. These procedures could be helpful for different objectives related to genetic diversity in alfalfa populations: analysis of breeding programs or genetic resources management. The use of SSR markers to detect differences among cultivars (that usually is a critical step in variety registration due to low among-cultivar distinction for quantitative traits) requires further studies based on a wider range of variation.

References

Armstrong JM (1954) Cytological studies in alfalfa polyploids. Can J Bot 32:531–542

Bataillon TM, David JL, Schoen DJ (1996) Neutral genetic markers and conservation genetics: simulated germplasm collections. Genetics 144:409–417

Bever JD, Felber F (1992) The theoretical population genetics of autopolyploidy. Oxford Surv Evol Biol 8:185–217

Boutin-Ganache I, Raposo M, Raymond M, Deschepper CF (2001) M13-tailed primers improve the readability and usability of microsatellite analyses performed with two different allele-sizing methods. BioTechniques 31:24–26

Brookfield JFY (1996) A simple new method for estimating null allele frequency from heterozygous deficiency. Mol Ecol 5:453–455

Brummer EC, Kochert G, Bouton JH (1991) RFLP variation in diploid and tetraploid alfalfa. Theor Appl Genet 83:89–96

Cheung W, Hubert N, Landry B (1993) A simple and rapid DNA microextraction method for plant, animal, and insect suitable for RAPD and other PCR analyses. PCR Methods Appl 3:69–70

Crochemore ML, Huyghe C, Kerlan MC, Durand F, Julier B (1996) Partitioning and distribution of RAPD variation in a set of populations of the Medicago sativa complex. Agronomie 16:421–432

Crossa J, Vencovsky R (1997) Variance effective population size for two-stage sampling of monoecious species. Crop Sci 37:14–26

Demarly Y (1954) Etude de l’hérédité de la bigarrure de la fleur chez la luzerne. Ann Amélior Plantes 4:5–20

Diwan N, Bhagwat AA, Bauchan GR, Cregan PB (1997) Simple sequence repeat DNA markers in alfalfa and perennial and annual Medicago species. Genome 40:887–895

Estoup A, Angers B (1998) Microsatellites and minisatellites for molecular ecology: Theoretical and empirical considerations. Advances in Molecular Ecology 306:55–86

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2003) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164:1567–1587

Gallais A (2003) Quantitative genetics and breeding methods in autopolyploid plants. INRA Editions, Paris, France

GEVES (1993) Bulletin des variétés: plantes fourragères. Première partie: fourragères pérennes 1991–1993. GEVES, Guyancourt, France

GEVES (2001) Les variétés de plantes fourragères inscrites au Catalogue Officiel Français 1994–2001. GEVES, Guyancourt, France

Ghérardi M, Mangin B, Goffinet B, Bonnet D, Huguet T (1998) A method to measure genetic distance between allogamous populations of alfalfa (Medicago sativa) using RAPD molecular markers. Theor Appl Genet 96:406–412

Irwin JAG, Lloyd DL, Lowe KF (2001) Lucerne biology and improvement - an analysis of past activities and future goals in Australia. Aust J Agric Res 52:699–712

Jarne P, Lagoda PJL (1996) Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends in Ecology& Evolution 11:424–429

Jenczewski E, Prosperi JM, Ronfort J (1999) Evidence for gene flow between wild and cultivated Medicago sativa (Leguminosae) based on allozyme markers and quantitative traits. Am J Bot 86:677–687

Julier B, Flajoulot S, Barre P, Cardinet G, Santoni S, Huguet T, Huyghe C (2003) Construction of two genetic linkage maps in cultivated tetraploid alfalfa (Medicago sativa) using microsatellite and AFLP markers. BMC Plant Biol 3:9

Kubik C, Sawkins M, Meyer WA, Gaut BS (2001) Genetic diversity in seven perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) cultivars based on SSR markers. Crop Sci 41:1565–1572

Labombarda P, Pupilli F, Arcioni S (2000) Optimal population size for RFLP-assisted cultivar identification in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Agronomie 20:233–240

Liu KJ, Goodman M, Muse S, Smith JS, Buckler E, Doebley J (2003) Genetic structure and diversity among maize inbred lines as inferred from DNA microsatellites. Genetics 165:2117–2128

Lonnet P (1996) Objectifs et critères actuels de la sélection des luzernes pérennes. Fourrages 147:303–308

Maureira I, Ortega F, Campos H, Osborn T (2004) Population structure and combining ability of diverse Medicago sativa germplasms. Theor Appl Genet 109:775–782

Mengoni A, Ruggini C, Vendramin GG, Bazzicalupo M (2000) Chloroplast microsatellite variations in tetraploid alfalfa. Plant Breed 119:509–512

Mengoni A, Gori A, Bazzicalupo M (2001) Use of RAPD and microsatellite (SSR) variation to assess genetic relationships among populations of tetraploid alfalfa, Medicago sativa. Plant Breed 119:311–317

Michaud R, Lehman WF, Rumbauch MD (1988) World distribution and historical development. In: Hanson AA, Barnes DK, Hill RR (eds) ASA, CSSA, SSSA, Madison, WI, pp Agronomy, Series of Monographs 29:25–91

Moody ME, Mueller LD, Soltis DE (1993) Genetic variation and random drift in autotetraploid populations. Genetics 134:649–657

Morales Corts MR, Crespo Martinez MC (2000) Variation of PGM and IDH isozymes for identification of alfalfa varieties. Euphytica 112:137–143

Nei M (1973) Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70:3321–3323

Nei M, Roychoudhury AR (1974) Sampling variances of heterozygosity and genetic distance. Genetics 76:379–390

Petit RJ, El Mousadik A, Pons O (1998) Identifying populations for conservation on the basis of genetic markers. Conservation Biology 12:844–855

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

Pupilli F, Businelli S, Paolocci F, Scotti C, Damiani F, Arcioni S (1996) Extent of RFLP variability in tetraploid populations of alfalfa, Medicago sativa. Plant Breed 115:106–112

Pupilli F, Labombarda P, Scotti C, Arcioni S (2000) RFLP analysis allows for the identification of alfalfa ecotypes. Plant Breed 119:271–276

Raymond M, Rousset F (1995) An exact test for population differentiation. Evolution 49:1280–1283

Riday H, Brummer EC, Campbell TA, Luth D, Cazcarro PM (2003) Comparison of genetic and morphological distance with heterosis between Medicago sativa subsp. sativa and subsp. falcata. Euphytica 131:37–45

Ronfort J, Jenczewski E, Bataillon T, Rousset F (1998) Analysis of population structure in autotetraploid species. Genetics 150:921–930

Stanford EH (1951) Tetrasomic inheritance in alfalfa. Agron J 43:222–225

Thrall PH, Young A (2000) AUTOTET: A program for analysis of autotetraploid genotypic data. J Hered 91:348–349

Truong C, Palmé AE, Felber F, Naciri-Graven Y (2004) Isolation and characterization of microsatellite markers in the tetraploid birch, Betula pubescens ssp. tortuosa. Molecular Ecology Notes 5:96–98

Valizadeh M, Kang KK, Kanno A, Kameya T (1996) Analysis of genetic distance among nine Medicago species by using DNA polymorphisms. Breeding Science 46:7–10

Volenec JJ, Cunningham SM, Haagenson DM, Berg WK, Joern BC, Wiersma DW (2002) Physiological genetics of alfalfa improvement: past failures, future prospects. Field Crop Res 75:97–110

Weir BS (1996) Genetic data analysis II. Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers, Sunderland, Massachusetts

Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1984) Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 68:1358–1370

Wright S (1951) The genetical structure of populations. Ann Eugen 15:323–354

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by A. Charcosset

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flajoulot, S., Ronfort, J., Baudouin, P. et al. Genetic diversity among alfalfa (Medicago sativa) cultivars coming from a breeding program, using SSR markers. Theor Appl Genet 111, 1420–1429 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-005-0074-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-005-0074-4