Abstract

This chapter addresses child well-being from a psychological point of view. In doing so, we need to remember that psychology is not one single discipline but covers a wide range of psychological disciplines from evolutionary psychology and behavior genetics via psychometrics to developmental, cognitive, personality, and social psychology – all of them relevant to the psychology of child well-being. The psychological study of well-being has a history of approximately 2,500 years. The modern psychological study of well-being and its close relatives, resilience, and prosocial behavior belong together under a common umbrella called “positive psychology.” In this chapter, we draw upon both of the ancient and the modern tradition. We have addressed the concept of well-being from both a theoretical and an empirical position. Yet, we have to admit that there is no unified way of sorting all the terms associated with the psychological study of well-being. Consequently, terms like happiness, subjective, emotional, affective, cognitive, mental and psychological well-being, life satisfaction, satisfaction with life, quality of life, enjoyment, engagement, meaning, flow, and hedonic balance have not been used consistently trough out the chapter.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Life Satisfaction

- Prosocial Behavior

- Satisfaction With Life Scale

- Positive Mental Health

- Parent Proxy Report

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction: Arne Holte

This chapter addresses child well-being from a psychological point of view. In doing so, we need to remember that psychology is not one single discipline but covers a wide range of psychological disciplines from evolutionary psychology and behavior genetics via psychometrics to developmental, cognitive, personality, and social psychology – all of them relevant to the psychology of child well-being. The psychological study of well-being has a history of approximately 2,500 years. The modern psychological study of well-being and its close relatives, resilience, and prosocial behavior belong together under a common umbrella called “positive psychology.” In this chapter, we draw upon both of the ancient and the modern tradition. We have addressed the concept of well-being from both a theoretical and an empirical position. Yet, we have to admit that there is no unified way of sorting all the terms associated with the psychological study of well-being. Consequently, terms like happiness, subjective, emotional, affective, cognitive, mental and psychological well-being, life satisfaction, satisfaction with life, quality of life, enjoyment, engagement, meaning, flow, and hedonic balance have not been used consistently trough out the chapter.

A large number of experts on the psychology of child well-being have contributed to the chapter. The chapter starts by framing well-being into the tradition of positive psychology (Wold) and tracing the greater historical lines (Vittersø), before we introduce current psychological conceptualizations of well-being (Vittersø), resilience (Friborg), and prosocial behavior (Bekkhus and Bowes). We then discuss psychological measurements of well-being in general (Røysamb) and indicators (Casas) and methods of measurement (Casas) used with children and adolescents in special. We ask who we should trust in – childrens’ own assessments or their parents’ (Jozefiak), before we address health and health-related quality of life as indicators of well-being (Holte). We present examples of how well-being is distributed among children in different countries (Wold) and ask whether such measurements are valid and what influence them across cultures and countries (Trommsdorff). We continue by – on a broad base – to single out what affects the experience of well-being generally and among children and adolescents particularly. The issues covered are evolution (Grinde), genes (Nes), cognition (Thimm and Wang), personality (Torgersen and Waaktaar), family (Bowes and Bekkhus), transfer of values between parents and child (Headey, Muffels and Wagner), play (Borge), peer relations (Borge), kindergarten (Zachrisson and Lekhal), and school (Barry). We end the chapter by presenting five ways to practically enhance happiness in everyday life (Nes and Marks) and by guiding you through the world’s largest database on happiness – the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven).

2 Conceptualization

2.1 Positive Psychology: A Framework for Studying Subjective Well-Being: Bente Wold

Subjective well-being (SWB) is one of the most prominent topics in the study of positive mental health and attracts increasingly more attention in psychology, in particular in the branch of positive psychology. Positive psychology was introduced as a new area of psychology in 1998, when Martin Seligman chose it as the theme for his term as president of the American Psychological Association. According to Seligman (2002b, p. 3), “The aim of positive psychology is to catalyse a change in psychology from a preoccupation only with repairing the worst things in life to also building the best qualities in life.” The first Handbook of Positive Psychology (Snyder and Lopez 2002) emerged in 2002, identifying several broad topics to be studied in positive psychology, such as identifying human strengths, fostering well-being, resilience, prosocial behavior, and quality of life (QOL). In this perspective, strategies and techniques for enhancing the well-being are educational, relational, social, and political interventions, not clinical treatments.

An important task in positive psychology is to get insights into well-being and QOL in terms of three overlapping paths or pursuits: (1) the pleasant life, or the “life of enjoyment,” how people optimally experience, forecast, and savor the positive feelings and emotions that are part of normal and healthy living (e.g., relationships, hobbies, interests, and entertainment); (2) the good life, or the “life of engagement,” the beneficial effects of immersion, absorption, and flow that individuals feel when optimally engaged with their primary activities; and (3) the meaningful life, or “life of affiliation,” how individuals derive a positive sense of well-being, belonging, meaning, and purpose from being part of and contributing back to something larger and more permanent than themselves (e.g., nature, social groups, organizations, movements, traditions, belief systems).

Among children, the three paths are present in many areas of life, and play is among the most evident. Playing is for children and positive psychology seeks to preserve this zest for movement as children grow older (for details, see Sect.20.4.8). Physical education can illustrate how students could learn to become excited about physical activity through a positive psychology approach. When individuals are aware of, pursue, and blend all three lives (the pleasant life, the engaged life, and the meaningful life), authentic happiness or the full life is more likely to be achieved. Moreover, inherent to positive psychology is the assumption that schools are integral in the promotion of positive human development. Given the need to create and sustain meaningful experiences for all students, the pursuits of positive psychology appear to be a natural match with quality physical education. Interesting, challenging, and pleasurable physical activity would internalize an authentic feeling of happiness in students (Cherubini 2009).

In their chapter on “Positive Psychology for Children,” Roberts and colleagues (2002) suggest that the focus in child psychology increasingly has become one of perceiving the competence of the child and his or her family and enhancing growth in psychological domains. The previous perspective of coping as a response to a stressor has been confronted with an increasing recognition that growth and SWB occur through adaptations to an ever-changing environment in a child’s life. Child well-being in a positive psychology perspective entails the understanding of positive development resulting from constructive and productive socialization and individuation processes. Through socialization, the child becomes integrated into society as a respected participant, by being able to establish and maintain relations with others, to become an accepted member of society at large, to regulate one’s behavior according to society’s norms, and generally to get along well with other people. Individuation requires distinguishing oneself from others, by forming a personal identity, developing a sense of self, and finding a special place for oneself within the social network. There is a dialectical interplay between the needs of the child to maintain relations with others and the needs of the child to construct a separate self. Child well-being may be considered as a product of fruitful experiences during socialization and individuation. The task at hand for positive psychologists is to examine how individual and social resources can be strengthened to ensure a positive outcome of these processes.

The process of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances, denoted as resilience, has attracted particular interest. The best-documented asset of resilient children is a strong bond to a competent and caring adult, who need not be a parent (Masten et al. 2011). According to Masten and colleagues (2011), resilience arises from ordinary protective processes and strengths such as self-regulation skills, good parenting, community resources, and effective schools. Resilient youth have much in common with competent youth who have not faced adversity, in that they share the same assets. For example, youth growing up in an adverse environment characterized by poverty may excel in academic achievement if they experience good parental support.

Resilience may be fostered by risk-focused strategies aimed at reducing the exposure of children to hazardous experiences or asset-focused strategies to increase the amount of, access to, or quality of resources children need for the development of competence. Such strategies may include providing a tutor and building a recreation center with structured activities for children or programs intended to improve parental and teacher skills (for details, see Sect. 20.2.4).

According to the self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci and Ryan 2012), child well-being depends on the extent to which the social environment provides opportunities for satisfaction of three innate psychological needs – competence, autonomy, and relatedness. When children feel competent, autonomous, and socially accepted, they are more likely to develop self-regulation skills and to be intrinsically motivated for positive behavior, which in turn may instigate feelings of satisfaction and well-being. Prosocial behavior, defined as helping behavior or acts undertaken to protect or enhance the welfare of others, may serve as an example. SDT posits that the degree to which a prosocial act is volitional or autonomous predicts its effect on well-being and that psychological need satisfaction mediates this relation (Weinstein and Ryan 2010). The authors suggest that engaging in prosocial behavior can foster competence, need satisfaction, and well-being because helpers are acting on the world in ways that directly result in positive changes. Moreover, helping is inherently interpersonal and thus impacts relatedness by directly promoting closeness to others and cohesiveness or intimacy. Finally, prosocial actions that are volitional also provide opportunities to experience autonomy, need satisfaction, and the positive states that derive from these prosocial actions (for details, see Sect. 20.2.5).

2.2 A Brief History of Well-Being: Joar Vittersø

Although research on child well-being is a relative newcomer, it is clearly grounded in ideas that are as old as history itself. Systematic thinking on well-being began with the antique concept of eudaimonia, a term frequently rendered in psychological literature as only referring to Aristotle’s ideas on happiness. This is misleading since the word was in use over 100 years before Aristotle was born and because Aristotle only formed one of several schools of ancient eudaimonia (McMahon 2006). Competing eudaimonic theories included hedonism, which may sound like a contradiction to modern psychologists. But for the ancients, hedonism was a conceptual option within eudaimonia (Keyes and Annas 2009). One should also bear in mind that the well-being of children was not a matter of interest for the ancient Greeks. Aristotle, for instance, claimed that children could never achieve eudaimonia.

Psychologists often point out that eudaimonia is a combination of “eu” (good) and “daimon” (spirit) and that the daimon part refers to an “inner self” (e.g., Ryan and Deci 2001; A. S. Waterman 1993). Such a translation is unfortunate since the Greek “daimon” referred to the spiritual and immortal part of the person, and it contrasted in this respect the term “eidolon,” which was the individual and earthly part of a person. To be eudaimon meant to be fortunate enough to lead a life that was blessed in a spiritual and not an individualistic way (McMahon 2006).

Disagreements existed in the ancient worldview as to what eudaimonia comprised. Radical versions of hedonism, like the one proposed by Aristippus, claimed that the goal of life is nothing else than maximizing feelings of pleasure, regardless of its source. This theory from the fourth century BCE banished thought in all its forms as a foreign element in a good life (Watson 1895). A more moderate version of antique hedonism was articulated by Epicurus, who surely prized the pleasures of life but who also believed that the kind of pleasures that we today refer to as satisfaction is needed in order to live a good life. And satisfaction (or “ataraxia” in classic Greek) was not achieved without living virtuously and having friends (Tiberius and Mason 2009).

Aristotle’s position was different and more complex. He considered eudaimonia to follow from the “activity of the soul in accordance with virtues” (McGill 1967, p. 17) and that hedonism, in the sense of searching pleasure only for its pleasantness, was a vulgar ideal, one that led people to become as slavish as grazing animals (Aristotle 1996). Different understandings of Aristotle’s thinking exist, partly because his writing was, to put it mildly, not always consistent. But philosophers seem to agree that Aristotle considered eudaimonia to depend upon virtuous activities. To be happy, a person must develop wisdom and exercise excellence in virtuous activities so that he (it was always a he in Aristotle’s writing) could realize his true and best nature and thus live a complete life (Waterman 2013). The conditions Aristotle considered necessary for the realization of one’s potential is more controversial. He did, for example, believe that abundance of possessions and slaves, combined with a noble birth, numerous friends, good friends, wealth, good children, numerous children, a good old age, bodily excellences (such as health, beauty, strength, stature, and fitness for athletic contests), a good reputation, honor, good luck, and virtue were needed in a happy life.

Socrates was supposedly the first individual who believed that humans could exercise some control over their own happiness. Good lives are attainable for those who make good choices. But in order to choose well, one needs insight – and it takes an appropriate education to develop such wisdom. With the rise of Utilitarianism, which of course happened much later, wisdom was no longer considered necessary for a good life. The only requirement for happiness was freedom, and this ideology still dominates contemporary thinking, in science as well as in political rhetoric.

Another major development in the history of well-being preceded Utilitarianism by a 100 years or so and came with the early phase of the Enlightenment. Here, not only freedom but also equality and good social networks were considered important for a happy life (cf. the “Liberty, equality and brotherhood” motto for the French revolution). When Thomas Jefferson penned the well-known phrase about happiness in the US Declaration of Independence, he was clearly inspired by this school of thoughts. Indeed, Jefferson launched the idea that the right to the pursuit of happiness is a self-evident truth with both private pleasure and public welfare in mind. He considered the reconciliation of public and private happiness as essential and believed that religion would ensure that “the pursuit of private happiness would not veer off the thoroughfare of the public good” (McMahon 2006, pp. 330–331).

The influence from the Enlightenment and the Utilitarianism can easily be observed in social sciences today. The development of economics, for example, is essentially lodged within the ideological legacy of Bentham. Empirical well-being research in psychology was similarly inspired (Bradburn 1969), although the notion of life satisfaction, the essence of which was initially proposed by Epicurus and later by John Stuart Mill, was a major source of inspiration as well (Campbell 1976; Cantril 1965). And even if happiness played a small role in the early years of psychology, it has always been a part of the discipline (Jones 1953). A substantial growth in happiness research began with Jahoda’s reflections on positive mental health (Jahoda 1958) and continued with the availability of well-being data from representative samples of the populations in the USA and other countries (Bradburn 1969; Cantril 1965; Nowlis and Nowlis 1956). Part of this development includes the birth of the subdiscipline of child well-being, which arose as a “social indicator” movement (Ben-Arieh 2008), and was pioneered by reports on the “State of the child” from the USA in the 1940s. The interest was also fuelled by the general progress of the concept of children, as evolved in developmental psychology, in the emerging notion of children’s rights, and in the expansion of available data. Comprehensive reviews of these trends are provided by Ben-Arieh (Ben-Arieh 2000, 2001, 2005; Ben-Arieh and Frones 2007) and others (Bradshaw and Hatland 2006; Casas 2000; Frones 2007).

2.3 Current Conceptualizations: Joar Vittersø

There is a confusing mixture of well-being concepts in the happiness literature. The most critical issue in the definitional debates concerns the number of dimensions needed to account for a life well lived. According to radical hedonism, we only need one: the balance of momentary pleasures over momentary pains (the so-called hedonic calculus). Kahneman (1999) positioned himself very close to this hedonic ideal in his early thinking, as he used to argue that happiness is properly understood with reference to the “experiencing self.” In this view, a person is happy if engaged (enough of the time) in activities that he or she would rather have continued than stopped. Kahneman later turned around and is now prepared to include life satisfaction – the “remembering self” – as a second dimension of well-being. Hence, we can be happy in our lives or happy with our lives. Kahneman admits, however, that the two notions of happiness are not entirely compatible and that nobody seems to have solved the puzzle of balancing the essence of the experiencing with the essence of the remembering self into a unitary definition of well-being (Kahneman 2012).

The conflict between the experiencing self and the remembering/evaluating self has always been tricky. It can be recognized in the ancient tension between Aristippus and Epicurus and between Bentham and Mill during the advent of Utilitarianism. In modern philosophy, the controversy is sometimes referred to as the distinction between sensory hedonism and attitudinal hedonism (Feldman 2010), and in studies of well-being in the 1960s, Bradburn’s was a theory of the experiencing self, while Cantril’s was a theory of the evaluative self (Bradburn 1969; Cantril 1965). The two giant volumes on well-being in the 1970s – Andrews and Withey (1976) and Campbell, Converse, and Rodgers (1976) – clearly struggled with the same problem, and in the early 1980s, Veenhoven (1984) attempted to solve the puzzle by including both hedonic level and contentment as elements in his overall concept of a happy life. Diener (1984) did something similar when he claimed that both affective/emotional well-being and evaluative/cognitive well-being were major categories of SWB. A few years ago, Diener mobilized over 50 well-being researchers to sign up in agreement on the following definition of SWB: “Subjective well-being refers to all the various types of evaluations, both positive and negative, that people make of their lives. It includes reflective cognitive evaluations, such as life satisfaction and work satisfaction, interest and engagement, and affective reactions to life events, such as joy and sadness. Thus, SWB is an umbrella term for the different valuations people make regarding their lives, the events happening to them, their bodies and minds, and the circumstances in which they live” (Diener 2006, pp. 399–400).

Life satisfaction is the core concept in theories of SWB. Traditionally, the term referred to a rational comparison of what people have, to what they think they deserve and expect, or to which they may reasonably aspire(Campbell et al. 1976). Following this view, life satisfaction can be precisely defined as the perceived gap between aspiration and achievement, ranging from the perception of fulfillment to that of deprivation (see also Michalos 1985). Versions of the gap approach to life satisfaction are still thriving in some circles, such as the sustainable development movement, whose adherents suggest that satisfaction follows from fulfillment of basic physiological needs (O’Neill 2011), and the group of self-determination theorists, who consider satisfaction to come from fulfillment of basic psychological needs (Ryan and Deci 2001). But within the “Diener camp,” life satisfaction is considered to be a report of how a respondent reflectively evaluates his or her life taken as a whole (Eid and Larsen 2008).

The notion that every good element in life can be captured as either a pleasant affect or as an evaluation of life in terms of goodness or badness has been referred to as the hedonic well-being approach (Ryan and Deci 2001). By contrast, competing theories offer taxonomies that go beyond pleasant feelings and judgments of satisfaction. These approaches may be considered eudaimonic in the psychological sense of the term (Tiberius 2013). An early conceptualization within this framework was developed by Sen, who pointed out that even if life satisfaction is important, it cannot possibly be the only element in a good life (Sen et al. 1987). Deprived persons that are overworked or ill can be made satisfied by cultural norms and social conditioning, he argued, and came up with the idea of capabilities in order to remedy this shortcoming. Sen’s thinking is difficult to summarize, but very briefly it suggests that a concept of well-being must account for not only feelings and evaluations but also human functioning. To Sen, functioning is about life-styles: what a person manages to do or to be. A capability, on the other hand, reflects a person’s ability to achieve a given functioning. Capabilities reflect a person’s freedom of choice between possible life-styles (Sen 2000).

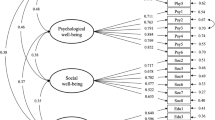

Ryff (1989) has voiced another critique of SWB. She borrowed Bradburn’s term “psychological well-being” and replaced his “affect balance” with what she believes are the six dimensions of well-being: self-acceptance, positive interpersonal relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, meaning in life, and personal growth. Although it is not quite clear why well-being consists in exactly these six dimensions, Ryff’s theory has for two decades spearheaded eudaimonic research. But other scholars have proposed alternative dimensions of well-being. For instance, Keyes (Michalec et al. 2009) developed a taxonomy of flourishing (his term for well-being) with three main categories: (1) emotional well-being (positive affect, happiness, and life satisfaction), (2) functional psychological well-being (the six Ryff dimensions), and (3) functional social well-being (his own five dimensions). The 14 subdimensions can be reduced into a single well-being scale that runs from languishing to flourishing. Huppert has identified ten features of well-being, combining both feeling and functioning (Huppert and So 2013). As previously described, Seligman (2002a) used to think that happiness was a three-dimensional phenomenon, whereas he more recently (Seligman 2011) has proposed a theory of well-being (called flourishing) with five elements: positive emotions (pleasure), engagement (flow), relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (or PERMA for short). Seligman’s theory is different from most other theories of well-being in several respects. He has, for instance, introduced a concern for accomplishment rather than for competence, the latter being the established concept of the domain. Seligman further holds emotions and satisfaction as practically overlapping, and he claims that neither is particularly important for well-being.

Other conceptualizations of well-being do indeed exist, such as those proposed by the “Stiglitz commission” (Stiglitz et al. 2009), the self-determination theory (Huta and Ryan 2010), the personal expressiveness approach to eudaimonia (Waterman et al. 2008), the Homeostatically Protected Mood theory of well-being (Cummins 2010), and very many others. Let us now move to the close relatives of the concept of well-being, namely, the concepts of resilience and prosocial behavior.

2.4 Resilience and Adaptation: Oddgeir Friborg

The concept of resilience was perhaps first introduced by Jack Block (1951). He launched the psychodynamically flavored term ego-resilience representing the ego’s ability to self-regulate impulses or behavior in a flexible manner. Although this ability is undoubtedly still highly relevant, resilience is nowadays construed as a phenomenon rather than a set of personality characteristics. It has therefore largely become an atheoretical concept.

One of the first to display a sincere interest in positive outcomes was Emmy Werner (Werner 1993). Her seminal longitudinal study, beginning in the 1950s, aimed to study risks of maladaptation among newborn children on the Island of Kauai. Many of these children grew up under multiple psychosocial risks, for example, poverty, chronic discord, or parental psychopathology. The focus of the study gradually changed as it was discovered that most children evaded the predicted doom of their inheritance and poor psychosocial surroundings. A positive developmental course was the normal (about 70 %) rather than the abnormal response to adversity (Werner and Smith 1992). Furthermore, it was observed that about half of the adolescents with considerable adjustment problems as teenagers still managed to become quite well-functioning adults. Werner’s study provides a rich source of insight into protective factors and case examples of positive human development.

What is resilience? It mainly refers to people adapting well despite expectations of the opposite, but it also embraces the developmental processes that facilitate favorable outcomes. As an outcome, resilience refers to a normal development or a successful adaptation despite experiences of significant adversity or trauma (Luthar 2006) or, simply put, normal adjustment despite abnormal circumstances. As a process, resilience refers to a range of psychological traits, skills, abilities, or coping mechanisms underlying favorable developmental trajectories. But resilience is not just about the positive forces within an individual but also about the developmental interplay between individual and environmental factors that together form an even stronger alliance against negative forces in life.

The number of factors identified to act protectively or buffer against stressors or life risks is staggering (Cederblad 2003; Luthar 2006), but they are clustered within three overarching domains: first, a broad set of personal, biological, genetic, temperamental, or dispositional traits, skills, abilities, or attitudes; second, as resources within the family in terms of stability and cohesion providing an environment of emotional closeness, empathy, and support; and third, a plethora of social and environmental resources that reinforce and support a healthy response. Examples may be friends, other family members, colleagues, or people in the neighborhood. It may also be institutions or community facilities offering proper housing, employment, social security, and health-care services (Luthar 2006; Werner 1993).

Resilience processes are inextricably related to the presence of stressors, hazards, or risks and are perhaps even pointless to infer in their absence. It is important to note that individuals characterized as resilient may still suffer from particular vulnerabilities that may create other or later problems, such as bouts of depression (Luthar et al. 1993) or problems with intimacy as adults (Werner and Smith 1992). But very often they do not allow their vulnerabilities to overshadow their behavioral strengths. They optimize the use of the resilience factors that are available to them in order to increase protection and readjustment. To reveal this pattern in research, one would in statistical terms look for an interaction between risk, vulnerability, and resilience factors. An example may be taken from the Dunedin longitudinal study. As expected, it was found that maltreatment or stressful life events early in life increased the risk of depression and suicidal attempts in adulthood. However, those individuals that had two long alleles in the HTTLPR serotonergic genotype were much less likely to suffer from these problems than those having two short alleles (Caspi et al. 2003). These genes were obviously important and protective but far less important for individuals growing up under favorable circumstances.

A later line of research has been concerned with understanding underlying mechanisms. An example is social competence which is found to protect against adult delinquency. This protection appears mediated by a reduced involvement with delinquent peers (Stepp et al. 2011). Hence, social competent adolescents are better able to resist becoming involved in deviant social networks. Studies of mechanisms (by examining mediators) are for that reason much more informative with regard to how to build intervention programs rather than just knowing that social competence counts.

A striking feature of the majority of resilience studies is that almost all find a subgroup ranging from about 50–75 % that come out favorably despite significant threats. An opportune question is therefore whether this is a universal phenomenon or perhaps an evolutionary property of humans. Do human variants always exist that are able to survive, no matter what dismal circumstances they may be subjected to? This is an intriguing idea that has been popular to many novelists and film directors. However, it rather seems that most of us may not escape psychological damages if the environmental hazards are abysmal enough or lasts long enough.

The studies which may illuminate this question are few, as well as ethically highly controversial. But a study by Egeland, Sroufe, and Erickson (1983) on mothers abusing their children physically and verbally, or who were psychologically unavailable or severely neglectful, showed that almost none of the children as six-year-olds escaped undamaged. Another line of studies deals with the Romanian orphanages which gave up children for adoption to the UK following severe to horrendous institutional deprivation (Rutter et al. 2007). Many of these were adopted to the UK, and all of these were grossly underdeveloped with respect to height and head circumference at entry. Although their developmental catch-up was almost complete in terms of weight and height, head circumference at the age of 11 was still below one standard deviation. As the children were adopted at different ages (<6, 6–24, and >24 months), the researchers could examine the impact of the duration of deprivation. On the positive side, all of the children had a considerable catch-up in the cognitive test scores (IQ) at age 6 and 11. However, the majority of the children older than 24 months at the time of adoption did not improve beyond an IQ score considered as very impaired (<70) (Beckett et al. 2006). These studies indicate that abysmal social and environmental surroundings are detrimental to human development the longer they are allowed to act.

A final, rare longitudinal study that deserves attention is the study by John Laub on the life course of delinquent teenagers growing up in low-income areas of Boston (Laub and Sampson 2003), following them from childhood to the age of 70. The most striking finding is the diversity in developmental trajectories. The authors reject the notion that early childhood experiences (e.g., antisocial behavior or poor school performance) are sturdy markers of long-term problems and criminal offense. Instead, they point to positive changes as a constant interaction of individual choices and environmental support. Despite early instability and family chaos, those who desisted from crime had some environmental factors in common: employment, military service, marriage, and living arrangements. Entering military service and becoming married represented turning points with respect to a change in antisocial or delinquent behavior. Although work was less influential in changing attitudes and behavior, it represented a strong protective factor in terms of routines, structure, and meaningful activities sustaining desistance from crime. Marriage was particularly protective as it provided limitations to socializing with delinquent peers. Enrolment in the military services acted protectively in a similar manner. Studies such as these illustrate the importance of social and structural support systems if a long-term positive adaptation is to be expected.

How do we measure resilience? One option could be to measure the positive outcome per se. However, instruments assessing protective factors are most probably a better approach as they are better suited to study how resilience mechanisms unfold over time. As our knowledge of protective factors has become extensive, it is quite surprising that valid instruments for assessing resilience factors are heavily underdeveloped. In a review of instruments measuring resilience, Ahern, Kiehl, Sole, and Byers (2006) identified six tenable scales. The Resilience Scale for Adults was one of these, which also is developed by the current author (Friborg et al. 2003). It received a good rating and is the only well-validated scale that measures resilience protective factors covering the three overarching clusters mentioned above: intrapersonal resources (positive perception of self, positive perception of future, social competence, and structured style), family cohesion, and social resources. In a range of studies, the RSA appears to be a valid measure predictive of efficient coping following stressful life events (Hjemdal et al. 2007), a higher tolerance of pain and stressful stimuli (Friborg et al. 2006), a more well-adjusted personality profile (Friborg et al. 2005), and less feelings of hopelessness (Hjemdal et al. 2012). It may be recommended for research on resilience and well-being.

2.5 Prosocial Behavior: Mona Bekkhus and Lucy Bowes

Prosocial behavior is thought to promote healthy development and well-being throughout development. Prosocial behavior is usually defined as voluntary behavior intended to benefit others (Eisenberg et al. 2006) and could reflect either internalized motivated behavior or behavior motivated by a general concern for others’ well-being. A number of empirical studies suggest that children begin to act in a prosocial manner very early in life (e.g., Svetlova et al. 2010; van der Mark et al. 2002) and that prosocial behaviors usually increase with age (Benenson et al. 2003). For example, infants have been found to show distress in response to another infant’s crying (Zahn-Waxler and Smith 1992), suggesting a predisposition for empathy. In a study examining prosocial behavior in toddlers, Svetlana and colleagues (2010) showed that toddlers as young as 18 months were able to instrumentally help adults and that the tendency to act in a prosocial manner increased significantly from 18 to 30 months of age. Moreover, in their meta-analysis, Eisenberg and Fabes (Eisenberg and Fabes 1998) found that prosocial behavior, such as sharing/donating, helping, and comforting others, was higher in adolescence than in childhood. However, longitudinal studies focusing on interindividual change and stability suggest that there are inconsistencies in the age-related increase in prosocial tendencies (e.g., Carlo et al. 2007; Hay et al. 1999). Nantel-Vivier, Kokko, Caprara, Pastorelli, Gerbino, Paciello, and coworkers (2009) examined prosocial behavior longitudinally across childhood and adolescence using a multi-informant, cross-cultural design. Their results indicate stable or declining levels of prosocial behavior over a 5-year period, from 10 to 14 and 15 years of age. Similarly, a study by Côté and colleagues (2002b) found a relatively high degree of stability in helping behavior over a 6-year period (6–12 years), using different raters over the study period. Thus, it appears that, although there are age-related changes in prosocial behavior, there is also a relatively high degree of continuity from childhood to adolescence.

Studies investigating the development of prosocial behaviors have largely focused on environmental influences of parenting, and twin studies have shown that positive and warm parenting promotes children’s prosocial behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al. 2006). However, it is increasingly recognized that environmental influences do not operate isolated from genetic influences (Rutter 2006). Thus, there is a need to focus on susceptibility to environmental influences. Research on parent-by-child temperament interactions, plasticity (Ellis et al. 2011), and differential susceptibility (Belsky et al. 2007) suggests that the characteristics of individuals (and their genotypes) may make them more susceptible to the rearing environment in a “for better or for worse” manner. That is, some children may, due to temperamental or genetic reasons, be more susceptible to both the adverse effects of, for example, parenting and the beneficial effects of supportive rearing (Pluess and Belsky 2009). Emerging evidence suggests that this may also be the case with prosocial behavior. For example, Knafo, Israel, and Ebstein (2011) examined the heritability of children’s prosocial behavior in 168 twin pairs. Their findings revealed an interaction pattern suggesting that some children might be more susceptible to their rearing context. That is, for children with the 7-repeat allele (DRD4-III polymorphism), prosocial behavior increased with an increase in maternal positivity. This linear relationship was, however, not found for the 7-repeat absent children. Children with the 7-repeat allele, whose mothers were the most positive, showed the highest levels of prosocial behavior. But children with the 7-repeat allele, whose mothers were the least positive, showed the lowest levels of prosocial behavior. Thus, it is clear that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to explaining individual differences in children’s prosocial behavior (for details, see Sect. 20.4.3).

In general, all children can act prosocially, but they differ in the frequency in which they engage in prosocial behavior and in their motives for behaving in a prosocial way. From a public health and well-being perspective, it is often thought that promoting prosocial behavior should encourage healthy development. For example, in a study by Côté and colleagues (2002a), girls who followed an abnormally low prosocial trajectory were at risk for developing conduct disorder in adolescence. The assumption is that promoting prosocial behavior in such groups may reduce the risk of conduct problems. At the opposite end of the continuum, very high prosocial behavior has been found to be a risk for depressive symptoms in 18-year-olds (Gjerde and Block 1991). Thus, both high and very low prosocial behavior may function as an additional risk for mental health, rather than promoting SWB and positive health.

3 Measurement

3.1 Measuring Well-Being: Espen Røysamb

In parallel with the conceptual and theoretical development of the well-being field, recent decades have witnessed an increased focus on measurement issues and methodological challenges. Is happiness measurable? And, if so, to what extent are measures reliable and valid? From a general skepticism toward measuring happiness, psychology has moved into developing and evaluating a number of well-being instruments. Based on recent developments, we now believe that measuring well-being is just as feasible as measuring, for example, mental disorders.

However, in contrast to mental disorders, well-being is typically measured as continuous rather than categorical phenomena. Clinical disorders such as anxiety and depression and neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD and autism are regularly defined by a set of criteria or symptoms, with a certain number of fulfilled criteria required to qualify for a diagnosis. Sum scores of symptom items are also used to represent continuous dimensions but then often with cutoff values to indicate severe symptom load or diagnostic level. Well-being instruments are primarily designed to capture degrees of well-being, ranging from low to high – without predefined cutoff values.

Whereas the general construct of QOL is sometimes measured by means of external criteria, such as access to education and health care, the psychological perspective on well-being focuses on the subjective or perceived aspects of the good life. Thus, well-being instruments aim to capture positive and negative emotions and cognitive evaluations of life. Accordingly, external factors, such as education and health care, are seen not as components of well-being but rather as possible sources and predictors of well-being.

As outlined, a number of well-being constructs have been developed: SWB, life satisfaction, positive affect, psychological well-being (PWB), mental well-being (MWB), personal well-being (PWB), flow, and hedonic balance. Correspondingly, several self-report instruments have been constructed. Central examples include the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985b) tapping the cognitive evaluative component of SWB; the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al. 1988), measuring affective components of SWB; and the Psychological Well-being Scales (Ryff and Keyes 1995), containing six subscales covering the PWB domain. Other examples include the General Happiness Questionnaire, the Authentic Happiness Inventory Questionnaire, the Basic Emotions State Test, the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire, the Personal Well-being Index, and Cantril’s Ladder (Diener et al. 2012; Eid and Larsen 2008; Ong and van Dulmen 2007) (for details, see Sect. 20.3.4).

In addition to questionnaire-based self-report instruments, the field has developed several alternative methods. One approach comprises various structured and semi-structured interviews. Another approach includes different versions of the Experience Sampling Method (ESM). The ESM approach aims to capture emotions and experiences in situ. Noteworthy are recent developments using modern technology, where research participants are prompted to fill out mini-questionnaires on their smartphones at random times during the day (Killingsworth and Gilbert 2010). A similar approach is seen in the Day Reconstruction Method (Kahneman et al. 2004), in which daily accounts of well-being and experiences are collected.

Valid measurements are essential for representing theoretical constructs and investigating causes and consequences of well-being. Yet measurement is not only an end result of conceptual theorizing but rather a critical feature in theoretical developments. Measurement efforts have contributed substantially to defining and refining constructs, to establishing boundaries between constructs, and also to delineating the underlying structure of well-being. For example, the theoretical distinction between the hedonic dimension of SWB and the eudaimonic dimension of psychological well-being has been supported in studies of the underlying structure of well-being scales (Ryan and Deci 2001) (see also Sect. 20.2.3).

Reliability and validity have been in focus during the development of well-being measures. Researchers have applied state-of-the-art methods, including item response models and structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate measurement equivalence, structural validity, and underlying latent structures (Ong and van Dulmen 2007). Thus, the most widespread instruments currently in use have well-established psychometric properties.

As well-being theories mainly have addressed adult well-being, measurement has also primarily been based on adult samples. However, recently there has been an important increase in research on measurement of child well-being (Casas et al. 2012c; Gilman and Huebner 2003). Several questions are being addressed: For which younger age groups may adult instruments be appropriate? For which age groups may adapted versions be feasible? Is the underlying structure of well-being similar among children and adults? As the field is moving forward, we anticipate high attention to measurement issues among children in the years to come, leading to validated instruments for all relevant aspects of well-being in different age groups. We move next to a brief review and outline of some promising developments in the measurement of well-being in children.

3.2 Do We Need Specific Indicators for Children and Adolescents?: Ferran Casas

May subjective information given by individual adults have any relevance at the macro-social level? Are subjective data from adults valid and reliable? Should we systematically collect some kinds of self-reported information from adults to better understand some social dynamics and some social changes involving them? Could that data from adults be useful for political decision-making? All of these questions were raised during the 1960s, when the so-called social indicators movement was born. One of the outstanding ideas of this movement was that we cannot properly measure social changes with only “objective” indicators. Subjective indicators are needed because people’s perceptions, beliefs, opinions, attitudes, and evaluations on their social life are also a part of the social reality and have much to do with social changes. Therefore, subjective indicators were proposed, which were considered to be relevant for political decision-making. Due to the lack of tradition of systematically collecting subjective data, a challenge was identified about how to produce them rigorously. Following Bauer’s proposals, subjective indicators should not only be “measures” but also other forms of evidence that enable us to assess where we stand and are going with respect to our values and goals and to evaluate specific programs and their impact (Bauer 1966).

More than 30 years later, exactly the same questions raised in the beginning of the last paragraph have been reformulated. The only difference is that the word “adults” has been substituted by “children and adolescents” (Casas 2011). Ben-Arieh (2008) pointed out the emergence of a “child indicators movement.” However, once again, our lack of scientific tradition is our main challenge. Do we need specific indicators for children and adolescents? We do not know for sure whether some indicators could be the same. Yet, from a psychological point of view, the more wise answer should be that the kind of relevant data to be collected may change with age. The fact is that national and international systems of statistics now include a large number of survey results from adults, but almost no data is collected systematically from children or adolescents in most countries.

In the international arena, UNICEF’s study coordinated by Adamson (2007) marked an important step toward the articulation of objective and subjective indicators for understanding children’s living situations in different countries. The study dealt with five major domains for children’s well-being, namely, material well-being, health and safety, educational well-being, young people’s relationships, behaviors and risks, and SWB. However, that pioneer study faced several limitations: (a) Only very few international databases exist with data provided by children themselves – for example, Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) (www.hbsc.org) and Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) (www.oecd.org/pisa). (b) Data in these databases include a limited number of countries, mostly developed countries. And, (c) the only psychometric scale included in international databases is the single-item scale named the “Cantril’s Ladder” (Cantril 1965). Using only a single-item scale for international comparison is too weak a solution when dealing with a young and controversial field of measuring as SWB still is at present. Additionally, it is doubtful that “SWB” should be considered a separate domain in life, rather than including a subjective view in any domain. The number of available multi-item scales to evaluate children’s and adolescents’ SWB in general (nonclinical) populations is still limited. Much more testing must still be developed between countries, cultures, and languages (Casas et al. 2012c). Scientific research on the psychosocial components of QOL during the 1960s and 1970s soon led from macro-social studies to micro-social studies of subjective or personal well-being. We were no longer interested only in the general well-being of populations. We also wanted to understand in more detail and with more precision the individual functioning that leads to people giving a positive evaluation of their own personal well-being. This made it even clearer that QOL research – and therefore well-being research – required not only an interdisciplinary approach but also a more micro-focused, even experimental research. Currently, we are still trying to understand the connections between SWB at a macro- and a micro-level. In psychology there is a long tradition of studying children’s and adolescents’ well-being at the micro-level. However – like in most human and social sciences – our major research has been focused on the negative aspects of well-being. Only very recently have we also been interested in the positive aspects and started to collect self-reported “positive” data from children and adolescents. We have long traditions collecting data from children for individual understanding. However, a feeling of “social and political relevance” of such data has often been missing. When we have asked children and adolescents for their own perceptions and evaluations very often, the data have not been as expected. Sometimes, we have doubted the reliability of the data. Sometimes we have doubted the reliability of the informants. The only evidence being that as researchers we did not have previous experience in asking the children (Casas 2011).

In the adult realm, it was assumed that social indicators could be “subjective” data or data obtained through subjective methods such as questionnaires, interviews, and discussion groups. This led to a debate over the epistemological “objectivity” versus “subjectivity” of the social phenomena being measured. Does “citizen dissatisfaction” with a service exist in the objective sense? If subjective measurement techniques indicate consistent dissatisfaction over time, may we then conclude that majority dissatisfaction “truly exists” and that it may have “real” and “objective” consequences? This debate recalled the famous quote that when people “define situations as real, they are real in their consequences,” including social and political consequences (Thomas and Thomas 1928, p. 572).

Although such considerations are also valid when referring to the youngest generations, the obvious political interest in collecting subjective data from children has been slow to develop. Child well-being was initially conceived at both the national and international level as “what follows from objective realities” such as rates of mortality, malnutrition, immunization, and disease. Nobody has denied the high usefulness of these data. What is surprising is that while “subjective adult satisfaction” with services and life conditions has become a very important policy issue, the satisfaction of children and adolescents continues to be treated as irrelevant. Too often, in the social and human sciences, the low reliability and validity of data obtained from children and adolescents are used as excuses to avoid collecting such data. Curiously, only advertisers and marketing experts appear to be interested in this population and to have “overcome” difficulties concerning validity and reliability (Casas et al. 2012b).

In addressing child well-being and QOL, we must not forget that by definition, QOL includes the perceptions, evaluations, and aspirations of everyone involved. We know that different social agents may perceive the same reality differently. This does not mean that some of them are right and all the others are wrong. Social realities are often comprised by different perceptions and evaluations of sets of various social agents, where all social agents are relevant for understanding the social dynamics involved. We cannot go on trying to explain social realities involving children based solely on our adult perspectives. Perspectives of children and adolescents are essential to understand their social worlds. In other words, we must not confuse child well-being with adult opinions of child well-being (for details, see Sect. 20.3.5). Both are important, but they are not the same, and both are a part of the complex social reality we call child well-being. Therefore, we face the challenge of filling the large gap of information concerning the younger population’s point of view of the social reality that affects humanity. Only in the last few decades have scientists become interested in studying child and adolescent well-being from the subjects’ own perspective. Until very recently, it was assumed that adult evaluations on children’s well-being would be valid enough.

A very recent international interdisciplinary initiative is trying to develop child-centered specific subjective indicators. Here they have proposed a new data collection in as many countries as possible using a questionnaire which explores children’s activities, perceptions, and satisfactions with regard to their everyday life. A range of life domains and children’s opinions on different topics affecting them is considered by means of three psychometric scales (International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISWeB) (http://childrensworlds.org/). Questions to children have been grouped in 10 sections, including yourself, your home and the people you live with, money and things you have, your friends and other people, the area where you live, the school, how you spend your time, more about you, how you feel about yourself, and your life and your future. In each section, there may be questions on definition of each child’s situation, on agreement/disagreement, on frequency, and on satisfaction. Satisfaction items can be grouped into eight life domains, in such a way that an index of each domain can be calculated, including household, material belongings, interpersonal relations, area of living, health, organization of time, school, and personal evaluations (feelings and beliefs). Three adapted versions of existing psychometric scales have been used in this project. These are the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) (Huebner 1991b), the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) (Seligson et al. 2003), and the Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) (Cummins et al. 2003). A first publication of results using a slightly modified version of this questionnaire and proposing an overall index on children’s SWB has been conducted by UNICEF-Spain: http://www.unicef.es/actualidad-documentacion/publicaciones/calidad-de-vida-y-bienestar-infantil-subjetivo-en-espana

Researchers need to develop much more research instruments and projects with “children’s advice” in order to be able to really capture what is relevant in children’s life and for children’s well-being from their own perspective (Casas et al. 2012b). Multi-method research, including qualitative data collection from children, is necessary to better understand children’s answer to our “adult” questionnaires, based on our worries and aspirations.

3.3 Measurement of Well-Being in Children and Adolescents: Ferran Casas and Bente Wold

In the recent years, at least three major child and adolescent personal well-being literature reviews have been published. One focused mostly on QOL, another on well-being, and a third on satisfaction (Andelman et al. 1999; Huebner 2004; Pollard and Lee 2003). These three concepts, although considered different by some authors, are very often used as interchangeable without defining them. In the tradition of social sciences, QOL is usually considered the broadest concept, while satisfaction is related to the cognitive aspects of SWB (see also Sect. 20.2.3). In health sciences, it has often been considered differently, although at present the most used concept is health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (for details, see Sect. 20.3.6).

These reviews show that most studies on child and adolescent well-being and QOL in the English-language literature have been focused on very specific, small populations, such as children with particular health problems. The reviews also show that in health sciences there are a great variety of quite specific instruments to assess “well-being” as an output of very concrete interventions among particular clinical populations, for example, children with cancer or with transplanted organs. In contrast, the social sciences are more devoted to investigating nonclinical populations, with larger samples, although the number of such studies is not large.

A number of psychometric scales have been used among regular populations of children and adolescents from the hedonic perspectives. However, up till now, there has not been a single eudaimonic scale available to study age groups under 16. Yet, a limited number of studies exploring different eudaimonic aspects of life have been undertaken. For example, one study addresses the relationship between future aspirations and SWB (Casas et al. 2007). Another study investigates associations between religion/spirituality and SWB (Casas et al. 2009). In different European countries, children were asked “Imagine that you are 21 years old. At that time, how much would you like people to appreciate the following aspects of you?” Unexpectedly, the most frequent answers chosen among lists of 16–26 qualities were niceness or kindness. In addition, it has been shown that in some countries, using religion and spirituality as the same life domain – as in the PWI – may be very confusing to adolescents, who consider these issues as very different.

Asking children directly about their perceptions, opinions, and evaluations of aspects and conditions of their life has produced surprising results. This has forced us to think critically about adult-held stereotypes and beliefs that for no good reason may generate bias among researchers and affect scientific understanding. A highly unsettling example is the history of child witness testimony studies. For more than two decades, researchers were interested only in cases in which children’s testimony was flawed. It was not until the 1980s that studies began to think from the point of view of the child. Then researchers were able to show that if children received an appropriate amount of support allowing them to feel comfortable, they could in fact be valid witnesses (Garbarino and Stott 1989).

Another example is the “discovery” of the decreasing life satisfaction from the age of 12 to the age of 16. In the scientific literature throughout the 1980s and 1990s, it was assumed that life satisfaction remains fairly stable throughout life, except for individuals with significant traumatic experiences. However, Petito and Cummins (2000) demonstrated that well-being decreased with age in an Australian sample of 12–17 years old. Later on, it was reported that in different samples of 12–16 years old from Catalonia, Spain (2003, N = 2,715; 2005, N = 5,140; 2007, N = 1,392; 2008, N = 2,841), using the PWI (Cummins et al. 2003), a decrease of overall life satisfaction with age was also observed (Casas 2011). More recently, SWB was assessed among adolescents using a range of six different instruments in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Spain. The aforementioned decreasing tendency was observed with all the instruments in all four different countries (Casas et al. 2012c). In the meantime, similar results have been reported also from Romania (Bălţătescu 2006), another Australian sample (Tomyn and Cummins 2011) (Fig. 20.1).

Change in SWB across age. Standardized mean across measures in each country, not weighted for different n; Brazil (age 12–16 years, N = 1 588; scales BMSLSS5it, Fordyce, HOL, OLS, PW17gr, and SWLS), Chile (age 14–16 years, N = 853; scales BMSLSS5it, Fordyce, HOL, OLS, PW17gr, and SWLS), Spain (age 12–16 years, N = 2 900; scales BMSLSS5it, Fordyce, HOL, OLS, PW17gr, PWIndex, and SWLS), and Romania (age 13–16 years, N = 930; scales OLS and PWIndex). Argentina not included because of low n. For full name and references to measure, see text

Recent findings from a large European study have identified similar trends (Currie et al. 2012). In the 2009/2010 survey of the Health Behavior in School-aged Children study (the HBSC study), satisfaction with life was measured in representative samples of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds from 39 countries. Life satisfaction was measured by the 11 steps of the “Cantril’s Ladder.” The top of the ladder indicates the best possible life and the bottom the worst. Respondents were asked to indicate the step of the ladder at which they would place their lives at present (from “0” to “10”). High life satisfaction was defined as reporting a score of “6” or more. More than 80 % of 11-year-olds reported high life satisfaction in all countries except Romania and Turkey. In 13 countries – including the Nordic countries and UK except Wales – more than 90 % of the children responded 6 or higher on the ladder. The proportion of children who reported high life satisfaction was highest in the Netherlands and lowest in Eastern European countries – 97 % among 13-year-old Dutch boys compared to 68 % of Turkish boys. As in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Spain, and Romania, prevalence of high life satisfaction significantly declined between ages 11 and 15 in almost all countries and regions for girls and in some for boys. Boys reported a significantly higher prevalence in most countries and regions at age 15 but in fewer than half at 13. There was less evidence of a significant gender difference at age 11. Gender differences were not large at any age and only exceeded 10 % in a few countries and regions at age 15. Affluence was significantly positively associated with high life satisfaction in nearly all countries and regions for boys and girls (for more on cross-cultural comparisons, see Sect. 20.4.1).

How come that these strong tendencies have not been detected earlier? One explanation may be that during the past century, most authors were using four- or five-point scales to assess SWB, life satisfaction, or happiness. Because of the non-normal distribution of the answers and the tendency in most populations to answer toward the positive end, the so-called optimistic bias (for details, see Sect. 20.4.4), such scales are not sensitive enough to catch differences in subgroups of the population. When researchers started to use eleven-point scales as recommended by Cummins and Gullone (2000), the age differences became visible, and the decreasing-with-age tendency became more and more obvious.

Taken together, these results pose a new question. Why is early adolescence a period of decreasing SWB – including overall life satisfaction – in so many countries? In addition, recent studies have cast doubt on the delicate assumption that parents transfer personal well-being to their children. In a sample of 12–16-year-old Catalan children and their parents, no significant correlations between parents and their children were found on global life satisfaction and in most life domains. The only exceptions were satisfaction with health and satisfaction with future security (Casas et al. 2008). Later on, with a much larger sample and more sophisticated data analyses, similar results were found by Casas, Coenders, and colleagues (Casas et al. 2011a), although interesting differences between parents of a boy and parents of a girls appeared (for further discussion, see Sect. 20.4.7).

3.4 Instruments: Ferran Casas

Researchers have developed a number of scales for assessing well-being, which are specific for children or adolescents. Some examples are Perceived Life Satisfaction Scale (PLSS) (Adelman et al. 1989), Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) (Huebner 1991b), Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scales (MSLSS) (Huebner 1994), Quality of Life Profile – Adolescent Version (QOLP-Q) (Raphael et al. 1996), Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale – Students Version (Com-QOL Students) (Cummins 1997; Gullone and Cummins 1999), and Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS) (Seligson et al. 2003). Some studies have also taken general scales developed for the whole (adult) population and successfully used them on adolescent samples, including Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al. 1985a), Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) (Cummins et al. 2003), and Fordyce’s Happiness Scale (FHS) (Fordyce 1988). The most frequently used scale with adolescents in the psychological scientific literature up till now is probably the single item on overall life satisfaction (OLS), which can be found with different wordings. The most frequently used multi-item scales with adolescents seem to be the SLSS, BMSLSS, PWI, and SWLS. By content, they seem like quite different scales. However, when used together, they tend to correlate rather strongly, usually between 0.50 and 0.65.

The OLS, SWLS (5 items), and SLSS (7 items) are context-free scales, while the MSLSS, BMSLSS, and PWI are based on the assumption that SWB or life satisfaction is composed by different life domains. The BMSLSS and the PWI seem to have fewer psychometric limitations when used with adolescents in international comparisons.

The SWLS was originally created to be used with adults and SLSS specifically for children and adolescents at 8 years old and on. The psychometric properties of the SWLS have been published in various articles. See, for example, Pavot and Diener (1993). The originally reported Cronbach α was 0.87 (Diener et al. 1985b). In the original testing, a single component accounted for 66 % of the variance.

The SLSS was designed by Huebner (1991b) as a seven-item context-free one-dimensional scale. Up until 1994, it was tested on small samples of children 10–13 years old (N = 79) (Huebner 1991a) and 7–14 years old (N = 254) (Huebner 1991b) in the USA using a four-point frequency scale (from never to almost always). Reported Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.73 (Terry and Huebner 1995) to 0.82 (Huebner 1991b; Huebner et al. 2003). In Fogle, Huebner, and Laughlin (2002), the scale is reported as a six-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and Cronbach’s alpha is reported at 0.86 (N = 160, 10–15 years old). Gilman and Huebner (2000) suggested caution with respect to assuming the comparability of scores across the two formats.

PWI includes items on satisfaction with seven overall abstract life domains. These are health, standard of living, achievements in life, personal safety, community, security for the future, and relationships with other people. It has an eighth optional item which does not function in all countries, namely, satisfaction with spirituality or religion. These life domains need rewording or even reformulation in some countries. For example, in Spanish samples, satisfaction with community was not understood by most adolescents and had to be substituted by satisfaction with groups of people you belong to. The psychometric properties of the PWI have been reported in Lau, Cummins, and McPherson (2005) and in International Wellbeing Group (2006). Cronbach’s α was originally reported to lie between 0.7 and 0.8. The seven original domains form a single component which predicts over 50 % of the variance for “satisfaction with life as a whole” with adult samples (Cummins et al. 2003). A School Children (PWI-SC), Preschool Children (PWI-PC), and Intellectual and Cognitive Disability (PWI-ID) versions are available in the Australian Centre on Quality of Life Web page (http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/auwbi/index-translations/wbi-school-english.pdf), which have been tested in Australian and Chinese samples.

In contrast, BMSLSS is composed of five very concrete life satisfaction domains. These are family, friends, school, oneself, and the place you live in. Why such concrete items usually correlate strongly with the more abstract items in the PWI and how the two kinds of items may be included in a common model are still unresolved questions. The psychometric properties of this scale have been published in different articles. A 0.68 Cronbach’s α was originally reported (Seligson et al. 2003).

The fact that most scales used with adolescents show a lower explained variance than the equivalent one with adults has raised a debate on what may be missing in the scales administered to adolescents. Currently, psychological literature is rich in publications that propose to include new life domains to the existing domain-based scales. For example, school satisfaction (Tomyn and Cummins 2011) and time use (Casas et al. 2011b) have been proposed to be included in the PWI. These scales have until now only been used with adolescents in a very limited number of countries. Yet, an increasing international testing has been observed during the recent years. The results obtained with these psychometric scales are promising and may lead to the development of well-grounded subjective indicators at the population level in countries that have versions adapted to their language and culture. Since most scales show a lower explained variance when used with adolescents than with adults, continue by discussing whether we should trust parents’ reports about their children’s well-being more than the children’s own reports.

3.5 Can We Trust in Parents’ Report About Their Children’s Well-Being?: Thomas Jozefiak

Because of the substantial discrepancy between child and parent reports on children’s well-being and QOL (Upton et al. 2008), a debate goes on in the literature about who is the most appropriate informant (Chang and Yeh 2005; Eiser and Morse 2001; Ellert et al. 2011). According to the World Health Organization, the concept of QOL is by definition based on the individual’s own subjective perspectives. However, younger children’s QOL report can be biased by several factors, among others their limited cognitive capacities and life experience (Spieth 2001). Therefore, for children up to ages 8–10 years, their parents are often asked to evaluate their children’s well-being and QOL. Many studies of QOL in adolescents have also used only parent reports. Thus, it is very important to know how well we can trust in such “proxy” reports.

In the general population, research comparing child and parent proxy reports showed that parents evaluated their child’s well-being and QOL as better than did the children themselves on most life domains (Ellert et al. 2011; Jozefiak et al. 2008; Upton et al. 2008). Further, parents in the general population reported only few changes related to one domain (school) of their children’s well-being and QOL over a 6-month period, while the children reported changes in many life domains such as family, emotional well-being, self-esteem, and school (Jozefiak et al. 2009). Parents’ own well-being has also been shown to be very weakly related to their children’s well-being (Casas et al. 2012a), and relationships between parents’ and children’s values are highly culture specific (Coenders et al. 2005).

In contrast to general population research, discrepancies between child and parent reports are not so obvious in clinical population studies. Generally, it has been shown that the strongest correlate of referral to child mental health care is the impact of child symptoms on parents (Angold et al. 1998). Furthermore, parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) reported lower adult QOL than parents of healthy children (Schilling et al. 2006). That is, child problems appear to have an impact on parents and could bias the parent proxy report of child well-being and QOL. For example, mothers of children referred to child psychiatry evaluated their children’s QOL as poorer than the children themselves reported (Jozefiak 2004). Also, parents’ own problems can influence parents’ proxy reports. Maternal depression was a significant predictor of total “proxy” QOL report, accounting for 12 % of the variance (Davis et al. 2008). These examples show that parents in clinical populations may underestimate their child’s “real” QOL. In somatic clinical populations, for example, obese children, these discrepancies may have different directions depending on the life domain being investigated (Hughes et al. 2007). There might be several interpretations of these findings, that is, the quality and psychometric properties of available parent–child measures and known and yet unknown factors affecting parent–child agreement levels and their direction (Upton et al. 2008). However, there is enough evidence indicating that parent proxy reports of child well-being and QOL are as biased as younger children’s self-reports but of course by different factors than in the child. Therefore, there is good reason to distrust parent’s report about their children’s well-being.

However, despite these disadvantages of parents’ reports, they obviously also have advantages, at least in the assessment of well-being and QOL in younger children. Parents have more developed evaluation capacities (consequence thinking, better sense of time – past and future, etc.), while children perceive and evaluate the quality of their lives more in the present moment. This becomes obvious especially in children with neuropsychiatric problems such as ADHD but also applies to the younger child without mental health problems.

What should we do in regard to the discrepancy between child and parent reports, if there is no “objective” gold standard? Instead of discussing who is the most appropriate informant about children’s well-being, it would be wiser to accept both advantages and disadvantages of both child and parent reports and consider them as valuable different perspectives, at least with regard to younger or severely ill children. By the definition of QOL, the child report should be considered as the prime authentic report whenever it can be obtained, and parent proxy report could represent important supplemental information about children’s well-being and QOL. However, if the child’s report cannot be obtained, maybe we could use the child’s health as a proxy for child well-being?

3.6 Health-Related Quality of Life: Can Health Complaints be Used to Indicate Well-Being?: Arne Holte

In epidemiological and clinical health research, symptom scales are among the most frequently used instruments to assess and monitor children’s and adolescents’ well-being. Several psychometrically sound scales and checklists are available, including the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman and Goodman 2009) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach 1991). Such symptom scales may tell us a lot about children’s symptom profiles. Unfortunately, however, they tell us little about children’s SWB or life satisfaction (LS). This is illustrated by a study of a representative sample of Norwegian 11–16-year-olds in 2009/2010 (part of the HBSC study; see Currie et al. 2012) – the correlation between an eight-item checklist of subjective health complaints (the HBSC symptom checklist; see Haugland and Wold 2001) and life satisfaction (measured by the 11-step Cantril’s Ladder; see Sects. 20.3.1–20.3.2) ranged from 0.39 among 11-year-old boys to 0.53 among 15-year-old girls. In the same study, subjective health as measured by a generic question was even more weakly related to life satisfaction (correlations ranging from 0.22 among 11-year-old girls to 0.36 among 13-year-old boys).

Strong self-reported health may occur together with low well-being. Weak self-reported health may occur together with high well-being (Fig. 20.2). Although to some extent correlated, health and well-being, therefore, have to be differentiated conceptually and measured separately and independently. Obviously, if we would wish to assess the degree to which the two influence each other, anything else would also be tautological.

Yet, within the field of health, the most frequent way of defining well-being is in terms of health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Modeled on the WHO definition of health from 1947, the construction of HRQOL instruments was guided by a consensus statement from an International Board of Advisors (Goodman and Goodman 2009). According to this, four fundamental dimensions are essential to any measure of HRQOL, namely, physical, mental/psychological, and social health, as well as global perceptions of function and well-being. In addition, pain, energy/vitality, sleep, appetite, and symptoms relevant to the intervention and natural history of the disease or condition were listed as important domains but left to the individual investigator to include or exclude.