Abstract

The aim of this article is to identify factors influencing well-being (whether positively or negatively) reported by children and adolescents from their own perspective, in the context of focus groups and individual interviews, and variations in their answers at two different points in time (one year apart), according to: 1) their previous scores (higher or lower) measured using psychometric scales of subjective well-being (SWB) and related constructs (temperamental traits, specifically via variables related to perceptual and pleasure sensitivity and life optimism), and 2) their age (measured through school year and classified into five cohorts). Important commonalites were observed in the answers reported by participants regardless of their prior levels of SWB and related constructs, the cohort they belonged to, the two separate data collections and the data collection technique used. This finding is interpreted as being due to the existence of a shared and fairly stable bottom-up effect in children and adolescents’ well-being. However, interesting discrepances are also observed between the groups of participants, which contributes to converging theoretical explanations arising out of two different traditions in the study of well-being (the hedonic and the eudaimonic), while also furthering scientific knowledge on how to better research children and adolescents’ well-being from a qualitative point of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Children and Adolescents’ Well-Being: Definition and Theoretical Approaches

Well-being has traditionally been studied from two main historical perspectives: the hedonic approach (referred to as subjective well-being: SWB), which focuses on happiness and defines well-being in terms of pleasure attainment and pain avoidance; and the eudaimonic approach (referred to as psychological well-being: PWB), which focuses on meaning and self-realization and defines well-being in terms of the degree to which a person is fully functioning (Deci and Ryan 2008; Ryan and Deci 2001). Despite the consideration by some authors (see Ryan and Deci 2001) that “well-being is probably best conceived as a multidimensional phenomenon that includes aspects of both the hedonic and eudaimonic conceptions of well-being” (p. 148), researchers have tended to focus on only one of the two approaches at a time, thus limiting knowledge regarding the broader concept of well-being. This tendency has been even more noticeable when studying children and adolescents’ well-being through the use of questionnaires, as there is a lack of eudaimonic scales for the population under 14 years of age.

Within the SWB tradition, some approaches initially developed for adults have also been applied to explain children and adolescents’ well-being (see Goswami 2014). According to the bottom-up approach, well-being is considered to be the accumulation of many small pleasures. In satisfaction terms, this would mean that satisfaction with specific domains leads to satisfaction with life as a whole. By contrast, top-down theories assume that there is a general global tendency to experience events in a positive way (Casas 1996), so that satisfaction with life as a whole would influence satisfaction with specific life domains (Diener et al. 2000). Of the best-known models arising out of the PWB approach, although described initially for adults, we find Ryff and Keyes’ multidimensional model (1995, quoted in Ryan and Deci 2001) and Ryan and Deci’s (2000, quoted in Ryan and Deci 2001) self-determination theory. The former considers autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery and positive relatedness as the key aspects for well-being, while the latter argues that the fulfilment of three basic psychological needs – autonomy, competence and relatedness - is essential for personal growth, integrity, experiences of vitality, self-congruence and well-being.

Both the bottom-up/top-down approaches and the multidimensional model/self-determination theory have generally been applied in the context of quantitative analysis. However, this cannot be said for data interpretation in qualitative studies in which specific domains having an impact on well-being are not defined by researchers beforehand. In this article, our initial premise is to consider that a qualitative approach to children and adolescents’ well-being based on prior quantitative data collection can contribute to identifying both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects and therefore ways to study children and adolescents’ well-being from a broader perspective. We also suggest that using theoretical formulations from both the SWB and PWB traditions to explain the specific factors participating children and adolescents define as influencing their well-being, can further our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

2 Constructs Related to Children and Adolescents’ Well-Being

While the SWB and PWB traditions coincide in considering that certain constructs contribute to children and adolescents’ well-being, including relationships with others (family and non-family members), social support and self-efficacy (e.g. Antaramian et al. 2008; Coyl-Shepherd and Newland 2013; Gilman and Huebner 2006; Leung et al. 2004; Oberle et al. 2011), other constructs have formed part of one tradition more than the other. This would be the case of autonomy and integration (e.g. Ryan and Deci 2001), which have been especially highlighted in the context of PWB, and school performance (e.g. Suldo and Huebner 2006) and personality traits (referred to as temperamental traits for the non-adult population) (e.g. Viñas et al. 2014), for which the SWB tradition has shown much more interest. Among personality traits, the literature highlights life optimism (Scheier et al. 1994) and openness to experience as having a strong impact on well-being, the latter being measured in childhood and adolescence through the dimensions of perceptual and pleasure sensitivity (Evans and Rothbart 2007).

Age is also an important factor in SWB, different cross-sectional studies (Baltatescu 2006; Casas et al. 2012; Currie et al. 2012; Goldbeck et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2015; Singh et al. 2015; Tomyn and Cummins 2011) and the few longitudinal studies conducted with children and adolescents (González-Carrasco et al. 2017) to date reporting a progressive decrease in levels of SWB from early to late adolescence. To the best of our knowledge, no qualitative longitudinal studies have considered changes in SWB with age during childhood and adolescence. According to the PWB tradition (Ryan and Deci 2001), basic psychological needs have an impact on well-being at all ages and it is how these needs are expressed and satisfied that changes with time. However, there is a lack of longitudinal studies on children and adolescents using PWB instruments to verify whether this assumption is also applicable to the non-adult population.

3 Methodological Approaches to Exploring Well-Being in Childhood and Adolescence: The Contribution of Qualitative Data

It is increasingly common to find qualitative-based research used to determine the reasons why children and adolescents consider certain domains or aspects of their life especially important to their well-being (e.g. Camfield et al. 2009; Coombes et al. 2013; Nic Gabhainn and Sixsmith 2006; Navarro 2011; Malo et al. 2012). For instance, using focus groups, September and Savahl (2009) found that safety, covering basic needs, community resources and psychological issues were the most important domains for South-African girls and boys between the ages of 9 and 16. Fattore et al. (2007) observed that children and adolescents aged 8 to 15 associated well-being with positive emotional states such as happiness, calm and excitation, but also with a sad life or being angry. However, when exploring children and adolescents’ opinions on this phenomenon, a higher or lower level of well-being has not been considered a relevant factor in any of the qualitative studies reviewed, with the exception of Navarro et al. (2017). Using focus groups, the said study found that those Spanish children who scored lower in SWB tended to refer more to relationships with friends and having basic needs covered as important factors for their well-being, whereas those scoring higher tended to refer more to family relationships and not having problems. However, the fact that this was a cross-sectional study limits our knowledge as to whether variations occurred over time.

Several techniques exist for obtaining qualitative information about children and adolescents’ well-being, among them: (1) interviews, which reveal personal histories and perspectives (Blasco and Otero 2008), and (2) focus groups, which help to construct narratives generated from the interaction of a small group in order to discover participants’ attitudes, feelings, experiences, opinions and beliefs on a topic, although they do not allow much learning about each individual (Escobar and Bonilla-Jimenez 2009). It is uncommon to use both focus groups and individual interviews to study the same children and adolescents’ well-being and further studies are therefore required that allow a comparison of the results obtained on the same questions using the two techniques.

Taking the aforementioned issues into account, the aim of this study is to identify factors influencing well-being (positively and negatively) reported by participants from their own perspective and variations in their answers at two different points in time (one year apart), according to: 1) their previous scores (higher or lower) for SWB and related constructs (temperamental traits, specifically via variables related to perceptual and pleasure sensitivity and life optimism), and 2) their age (measured using the school year they belonged to and classified into five cohorts). It is our belief that studying the perceived evolution of contributing factors to well-being over one year will provide different explanations about how children and adolescents perceive their well-being. A comparison of the results obtained from individual interviews and focus groups is expected to broaden scientific knowledge on how to better research children and adolescents’ well-being from a qualitative point of view.

We take the following research questions as a starting point:

-

1)

Will participants with low and high scores for SWB and related constructs (perceptual and pleasure sensitivity and life optimism) report an unequal number and type of perceived contributing factors to well-being (positive and negative)?

-

2)

Will participants enrolled in different school years report an unequal number and type of perceived contributing factors to well-being (positive and negative)?

-

3)

Will children and adolescents report the same number and type of contributing factors to well-being (positive and negative) after one year?

It is expected that participants with higher scores for SWB and related constructs will refer more to positive factors than negative ones when responding to the open question about what constitutes well-being for young people of their age. It is also expected that the older the participants, the more they will refer to negative factors and the more eudamonic factors will emerge. And finally, it is also expected that more factors will be reported in the second year of data collection due to the participants’ previous experience in the research process and the fact that they are one year older.

4 Method

4.1 Sample

The data presented in this study are part of a longitudinal study conducted over two academic years to explore the evolution of subjective well-being in children and adolescents aged 9 to 16. The participants were students attending 9 state-run and mixed-funding primary and secondary schools in Catalonia (north-east Spain). A questionnaire was used to collect data from 940 children and adolescents for two consecutive years, and 100 also participated in focus groups and individual interviews. The children and adolescents belonged to different academic years and were divided into five cohorts (Table 1). All cohorts correspond to compulsory education within the Spanish education system.

4.2 Instruments

A script of open questions was designed to explore qualitative data. It began with the question analysed in this article about what constitutes well-being. Ten focus groups and eight individual interviews were conducted with the same children and adolescents over two consecutive years, giving a total of 20 focus groups and 16 individual interviews.

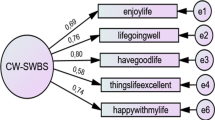

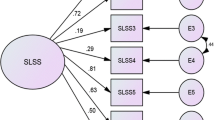

Participants in the focus groups and interviews were selected considering their previous scores on three psychometric scales measuring SWB and two scales for measuring temperamental traits related to SWB, all collected through a questionnaire administered in the first year of data collection. In the case of the focus groups, these were the: (1) Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS: Diener 1994), (2) Personal Well-Being Index (PWI: Cummins et al. 2003) and (3) Brief Multidimensional Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS: Huebner et al. 2006). A global SWB index was obtained for each participant by summing the scores for these three scales, and this was used to classify them into two groups according to whether they had a high or low level of SWB. For the interviews, we used the dimensions of pleasure sensitivity and perceptual sensitivity from the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised (EATQ-R: Ellis and Rothbart 2001), while life optimism was measured via the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R: Scheier et al. 1994). After summing up totals for these two scales, participants were also differentiated according to higher and lower scores.

4.3 Procedure

We contacted different schools in Catalonia (north-east Spain) to ask for their cooperation with the two-year project. Nine schools agreed to participate in both the quantitative and qualitative phases. Parents were also asked for their consent during the two years. Only boys and girls for whom we had received consent from parents or tutors and themselves answered the questionnaire and participated in the individual interviews or focus groups. With the objective of not losing sample size in the transition from primary to secondary education, thus affecting the second cohort (Table 1), collaboration was requested from the high schools attended by most of the students coming from the participating elementary schools. The focus groups were organized at the schools as follows: five groups of participants with the highest SWB scores and five with the lowest scores at their school (not for the whole sample), with five boys and five girls in each (Table 1).

Four individual interviews were conducted each year with boys and girls with both higher and lower scores in pleasure and perceptual sensitivity or life optimism, all of the same age: 15 year-olds at the time of the first interview (Year ten) and 16 at the time of the second, that is, a year later (Year eleven) (Table 1). To avoid introducing any bias, participants in both the focus groups and individual interviews were all told that they had been selected based on their responses to the questionnaire. The same explanation was given to teachers and principals of the schools, while the consent previously required from parents included the possibility of their children being interviewed after the questionnaire administration in order to obtain additional information.

Ethical standards for research involving children and adolescents in Catalonia were followed at all times, including asking for permission from the Department of Education of the Catalan Government, who communicated to the schools the institutional interest in being involved in the research process.

4.4 Data Analysis

We proceeded by transcribing all the materials from the focus groups and individual interviews and conducting a content analysis following the steps proposed by Bardin (2002). We conducted a first reading of the interviews in order to familiarize ourselves with the material and establish operational criteria for the analysis (segmenting the text into comparable units, choosing a means of encoding for recording information, etc.). In a second phase of exploring the material, we opted for categorical content analysis, which led us to use textual data to fragment text and group it into categories. To ensure inter-judge reliability (Neuendorf 2002), the process of categorizing the data and comparing them among the different groups was performed independently by two of the team’s researchers. Their analyses were compared and discussed at several team meetings, meaning the other members acted as a third judge. The criterion established to accept the various categories and subcategories as valid was for at least two judges to agree on the assessment.

After analysing all the responses, five qualitative categories were defined from the points participants said contributed to them having a more or less positive well-being at their age. These categories were analysed considering three axes: a) previous higher or lower scores in SWB, pleasure and perceptual sensitivity or life optimism (Table 2); b) the cohort participants belonged to (Table 3); and c) the first or second year of data collection (Table 4). In parallel, the results of the focus groups and individual interviews were also contrasted (Table 5). Consistent with the aim of the study and the research questions raised, the axes of analysis focused especially on mismatching factors between the different groups of comparison. In all tables, factors are analysed according to their content, whether they are thought to have a positive or a negative contribution to well-being and in relation to the number of focus groups and/or individual interviews in which they emerged.

5 Results

The opinions provided by children and adolescents have been classified into five categories: Interpersonal relationships, which refers to having good or bad relationships with family, friends and other people, Health, Leisure activities, the School domain and Personal aspects (Table 2). With regard to Interpersonal relationships, according to the participants, relationships with family and friends are key to well-being, specifically receiving support from family members and spending time with them. They highlighted the importance of their parents being happy. In contrast, the death or illness of a relative, family arguments, parental separation, and excessive parental control contribute to diminishing their well-being. All participants stated that having friends and enjoying time with them contribute positively to their subjective well-being, while getting angry and arguing with them leads to unease. They also feel bad when they have problems with people.

The participants noted the importance that they and their families enjoy good health. They considered that having specific unhealthy habits (not doing exercise and not eating well) lowers their well-being, while doing leisure activities and having fun helps them feel good. The participants’ experience of the school environment is another factor that clearly determines their well-being. There were conflicting discourses regarding the effects of the burden of homework and exams: for some, being able to do this is a synonym of being happy at school and getting good grades, whereas for others it leads to too much stress. Not passing exams despite having invested a lot of effort in studying also has a particularly negative impact on well-being. Other barriers to high levels of well-being are having to get up early to go to school, expulsions and punishments and having little free time.

Some personal aspects were identified as facilitators of well-being, such as being satisfied with yourself and having life goals. Having no problems or concerns, being sure about what you are doing and having self-confidence were all given as factors that make them feel good, while feeling afraid of being alone at home or of death are associated with lower levels of well-being.

-

a.

Differences between participants with higher and lower scores in SWB and related constructs

A majority of mismatching perceptions regarding factors that contribute to well-being between participants with higher or lower scores were only found in one or two focus groups and/or individual interviews (Table 2). Exceptions to this were mainly observed among the higher-scoring group and referred to the sub-category of family relationships and the category of personal aspects (mentioned in 3 to 5 cases). With regard to the lower-scoring group, the only exception observed referred to the sub-category of relationships with other people (mentioned in 3 cases). Participants with higher scores mentioned 18 factors they considered to make a positive contribution to their well-being, while those with lower scores mentioned only 3. The latter group referred to 8 negative contributing factors, compared to 5 by the group with higher scores (Table 2).

The most important differences between the high and low-scoring groups were in the sub-category of family relationships, with the former mentioning the importance of receiving support from parents and the latter highlighting the negative impact on well-being of not having any relative to turn to for help when needed (Table 2). Differences also appeared between the two groups in terms of leisure activities and personal aspects. In relation to the former, the higher-scoring participants emphasized the importance of leisure activities, while the other group did not mention any mismatching factor. With regard to the category of personal aspects, participants belonging to the higher-scoring group mentioned eudaimonic factors such as self-acceptance, self-belief and life objectives as important factors for well-being, while participants with lower scores referred to hedonic factors such as being satisfied and having no worries.

-

b.

Differences by cohort

A majority of mismatching perceptions regarding factors that contribute to well-being between participants belonging to different cohorts were mentioned in only one or two focus groups and/or individual interviews (Table 3). Exceptions to this were found in the first and the fifth cohort, where some factors were mentioned in three cases (1st cohort: spending time with the family; 1st and 5th: getting angry and arguing with friends, problems in relationship with friends; 5th: having problems with boy/girlfriend or splitting up with him/her, having good relationships with other people), and in four focus groups/individual interviews (5th: having self-confidence).

The number of positive factors mentioned decreases in the 3rd and 4th cohorts (to 10 and 9, respectively) compared to the 1st and 2nd (12 each), but increases considerably in the 5th cohort (20). The highest number of negative factors was found in the 5th cohort (12) followed by the 3rd cohort (8). Some of the factors identified were mentioned in four of the five cohorts considered, although they did not all follow the same pattern as they appeared in different cohorts. This was the case with: meeting, doing things and having fun with friends; doing leisure activities in their free time; and not having problems/worries. No clear pattern was observed in the different cohorts for the factors emerging in three of the five cohorts considered, with the exception of other people not respecting or listening to them, which appeared in the first three cohorts, not having problems at school, which was identified in the three middle cohorts, and having life goals, which emerged in the last three cohorts.

-

c.

Differences by year of data collection

Many of the factors that explain well-being according to the participants were mentioned in both the first and second focus groups and in the individual interviews. The category with the most common elements was interpersonal relationships. When comparing the two data collections, we observed that, with the exception of the factor of other people not listening to you, not trusting you and not caring about you and the factor related to accepting yourself (both factors were mentioned in the first data collection in 5 and 3 focus groups and/or individual interviews, respectively), the other factors were mentioned in only one or two cases (Table 4). In the first year of data collection, the participants mentioned 8 factors which make a negative contribution to well-being and 6 which make a positive contribution, while in the second year the proportion was 18 positive factors to 3 negative ones.

Important differences were observed between the first and second years of data collection for the sub-category of family interpersonal relationships, for which all mismatching factors were mentioned in the second year. Most of these were related to parents providing different kinds of support, but also them controlling too much. Perceptions regarding relationships with friends, but especially with people other than family and friends, seemed to change from fairly negative to more positive. The same applies for health and the school domain. There was also an important increase in the number and type of positive factors included in the personal aspects category.

-

d.

Differences by qualitative technique of data collection used

A majority of mismatching perceptions regarding factors that contribute to well-being between participants participating in focus groups and individual interviews were mentioned in only one or two focus groups and/or individual interviews (Table 5). However, the following exceptions to this were identified: being happy and content (mentioned in 5 focus groups and/or individual interviews), death or illness of a relative, getting bad marks, not having problems or worries, having self-confidence and life objectives (mentioned in 4), receiving respect, support, advice and help from friends, people not respecting you, criticizing you or taking advantage of you, having fun during leisure time, and having a lot of homework (in 3 focus groups and/or individual interviews).

A higher number of mismatching factors were observed for focus groups than individual interviews (38 and 10, respectively). In the case of individual interviews, more negative (7) than positive (3) factors emerged, while the contrary was found for focus groups (28 positive and 10 negative) (Table 5).

The most important differences between focus groups and individual interviews were found in the interpersonal relationships category, where all mismatching factors corresponding to the individual interviews were negative. In the school domain and within the personal aspects category, the nuances provided by participants in the focus groups were much more diverse.

6 Discussion

Important commonalites are observed in the answers reported by participants with higher or lower scores in SWB and related constructs (pleasure and perceptual sensitivity and life optimism), for the five different cohorts and across the two data collections, as demonstrated by the fact that the majority of mismatching factors were mentioned in only a small number of focus groups and/or individual interviews. This result is interpreted as being attributable to the existence of basic factors contributing to well-being across different ages and situations (see, for instance, Antaramian et al. 2008, Gilman and Huebner 2006) that can be identified regardless of the technique used to gather information, which reflects the existence of an important shared and fairly stable bottom-up effect for well-being among children and adolescents. Although a top-down effect is presumed to have exerted some impact on participants’ responses, especially among high-scoring ones for whom a stronger propensity to evaluate things in a positive way may have yielded to express more positive factors, further studies are needed to elucidate how bottom-up and top-down effects combine to give rise to different well-being profiles.

However, interesting discrepances are also observed between groups of participants, this being a novel contribution of this article. In relation to the first research question raised about whether participants with lower or higher scores for SWB and related constructs will report an unequal number and type of perceived contributing factors to well-being (positive and negative), it was expected that participants with higher scores would refer more to positive than negative factors and the contrary would be true for participants with lower scores. Our results corroborate this expectation and also reveal that participants with higher scores describe double the number of contributing factors compared to participants with lower scores, the difference being observed in all five categories considered.

As expected, some differences can also be identified between the two groups in the type of factors they mentioned. Participants with lower scores talked about the impact on well-being of not having any relative to ask for help when needed, while the higher-scoring group talked about the importance of receiving support from parents. This finding corroborates the great importance of receiving family support for children and adolescents’ well-being (Leung et al. 2004; Oberle et al. 2011: Coyl-Shepherd and Newland 2013). In contrast to the lower-scoring group, participants with higher scores also highlighted the importance of leisure activities, which coincides with studies connecting leisure activities to well-being (Newman et al. 2014). Interestingly, participants in the higher-scoring group placed far more emphasis on eudaimonic factors contributing to well-being (self-acceptance, self-belief and having life objectives), compared to the hedonic factors considered much more important by the lower-scoring group. This finding is in line with Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory, according to which hedonic factors do not necessarily contribute to high levels of well-being, while eudaimonic factors do. Because hedonic factors are also mentioned by the higher-scoring group, further research is needed in order to know how hedonic and eudaimonic factors combine to give rise to different well-being profiles.

The second research question focused on determining whether participants in different school years and therefore from five different cohorts reported an unequal number and type of perceived contributing factors to well-being (positive and negative). Our prior expectation was that the oldest participants would make more reference to negative factors than the youngest (González-Carrasco et al. 2017), and that more eudaimonic factors would emerge among the oldest (Ryan and Deci 2001). As expected, the oldest participants (5th cohort) reported far more negative factors than the participants in the other four cohorts. However, they unexpectedly reported far more positive factors at the same time. One possible explanation for this would be that their developmental cognitive growth gives them a greater ability to analyse their lives and they therefore take into account far more factors than younger adolescents and children. Participants in the 3rd and 4th cohorts were the ones who expressed the fewest positive factors, although a decrease in levels of well-being was expected in the second cohort on the basis of previous quantitative findings (González-Carrasco et al. 2017).

In accordance with expectations for this study, a clearly eudaimonic factor such as having life objectives was only found among the oldest participants. This finding could be explained by the fact that a eudemonic conception of well-being appears during the adolescent period, in contrast to previous ages, when a hedonic conception prevails (see Hallam et al. 2014). The above results have some practical implications for teachers, parents and researchers as they show the importance of taking into account the stage of development in which the child or adolescent is located when it comes to establishing the educational objectives and requirements to be asked of children and adolescents in terms of academic outcomes, behaviours and attitudes.

The third research question was whether information gathered in the first or second year of data collection yielded different perceived contributing factors to well-being after a one year period in terms of number and type of factors. Specifically, it was expected that more factors would be reported in the second year of data collection. Our analysis shows that many factors did emerge in both years, especially in the category of interpersonal relationships. However, important discrepancies can be also identified. First of all, the number of factors highlighted in the second year was higher than in the first. The category with most discrepancies was school aspects, followed by personal aspects and interpersonal relationships with people other than family and friends. Another important observation is that the number of negative factors mentioned decreased in the second year, which the reviewed literature has yet to provide a plausible explanation for.

Since the literature states that the use of different qualitative techniques leads to different results (e.g. Fattore et al. 2007; September and Savahl 2009), despite the fact the differences between them have not been studied systematically in the context of children’s and adolescents’ well-being studies, both focus groups and individual interviews were used in this research so as to compare the information obtained with each method. The comparison shows that beyond common factors emerging from both techniques, a high number of mismatching factors are observed. In the case of individual interviews, more negative factors emerge than positive ones, while the opposite is true of focus groups. It would not be unreasonable to think that individual interviews facilitate the emergence of more negative factors due to the fact that what is said is not shared with classmates (see Rodríguez 2006). At the same time, focus groups generate data subjected to group effects, meaning that dominant group members, peer pressure and other group dynamics may mediate participants’ responses (Kaplowitz and Hoehn 2001). In this respect, it could be hypothesised that participants with a more positive conception of well-being have exerted some influence over those with a more negative understanding.

Classifying the participants into different groupings allowed us to identify non-common factors that contribute to SWB, which would not have been possible without such groupings. Children and adolescents with higher SWB scores seem to perceive the different environments they are embedded in (school, family and friends) and even themselves differently than children and adolescents with lower SWB scores. It is not only that the former have a more positive perception than the latter, a result that was expected according to the top-down model of SWB, but also that they consider a wider range of factors, something more difficult to detect through quantitative methodology.

The comparison of children and adolescents in different cohorts has allowed us to observe that some factors remain important despite age, while some others are clearly related to age. Collecting information from a longitudinal perspective is not very common among qualitative studies focused on understanding children and adolescents’ well-being. Despite the fact that only two data collections were conducted, the comparison between the data obtained in the first and second years proved very helpful in observing unexpected results, such as fewer negative factors emerging in the second year. When the objective is to draw out diverse factors, focus groups would be preferable to individual interviews, the latter being more recommendable when the objective is to identify factors that make a negative contribution to well-being. In short, the findings of this study may be very helpful in planning actions to improve children and adolescents’ well-being since, thanks to the sequenced use of quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques, they provide in-depth information on factors that contribute to high levels of both SWB and PWB, which authors such as Ryan and Deci (2001) call optimal well-being.

The study is not exempt from limitations, the most important one being that only a two-year data collection was carried out. Future research should include participants from different cultural contexts in order to verify to what extent variations may exist in the way children and adolescents perceive their surrounding world according to the different groupings considered here, as the qualitative techniques used here may have yielded very much contextualised results which can make the generalization of the results obtained difficult.

Another limitation worth mentioning is the unequal number of participants in the individual interviews in comparison to those of focus groups. Besides the fact that in individual interviews only one participant at a time is considered, in contrast to focus groups in which from 8 to 12 participants are expected each time, individual interviews were only conducted with the oldest participants (5th cohort), thus limiting the comparison of the results coming from the two techniques. In this article, the grouping for individual interviews and focus groups was made using different scales measuring related constructs with an exploratory purpose. However, an in depth analysis of the results obtained through the two qualitative techniques would require that the grouping was made using exactly the same instruments.

References

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2008). Adolescent life satisfaction. Applied Psychology. An International Review, 57, 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00357.x

Baltatescu, S. (2006). Comparative results and psychometric properties of the personal well-being index- Romania (old and new versions) with an adolescent sample- a preliminary analysis. Retrieved from http://www.sergiubaltatescu.info/content/comparativePWI website.

Bardin, L. (2002). Análisis de contenido. Madrid: Ediciones Akal.

Blasco, T., & Otero, L. (2008). Técnicas conversacionales para la recogida de datos en investigación cualitativa: La entrevista (II). Nure Investigación, 34, may-june.

Camfield, L., Crivello, G., & Woodhead, M. (2009). Wellbeing research in developing countries: Reviewing the role of qualitative methods. Social Indicators Research, 90(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9310-z

Casas, F. (1996). Bienestar social. Una introducción psicosocial. [Social well-being. A psychosocial introduction]. Barcelona: PPU.

Casas, F., Sarriera, J. C., Abs, D., Coenders, G., Alfaro, J., Saforcada, E., & Tonon, G. (2012). Subjective indicators of personal well-being among adolescents. Performance and results for different scales in Latin- language speaking countries: A contribution to the international debate. Child Indicators Research, 5(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-011-9119-1

Coombes, L., Appleton, J., Allen, D., & Yerrell, P. (2013). Emotional health and well-being in schools: Involving young people. Children & Society, 27, 220–232.

Coyl-Shepherd, D. D., & Newland, L. A. (2013). Mothers’ and fathers’ couple and family contextual influences, parent involvement, and school-age child attachment. Early Child Development and Care, 183(3–4), 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.711599

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., van Pallant, J., Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective well-being: The Australian unity well-being index. Social Indicators Research, 64, 159–190.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., & Rasmussen, V. B. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. In W. R. O. F. Europe (Ed.), Health policy for children and adolescents (Vol. 6). Copenhagen: Who Regional Office for Europe.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

Diener, E. (1994). El bienestar subjetivo. [Subjective well-being]. Intervención Psicosocial, 3(8), 67–113.

Diener, E., Scollon, K. N., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Suh, E. M. (2000). Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgements: Global happiness is not the sum of its parts. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 159–176.

Ellis, L. K., & Rothbart, M. K. (2001). Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in child development. MN: Minneapolis.

Escobar, J., & Bonilla-Jimenez, F. (2009). Grupos Focales: una guía conceptual metodológica. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología, 9(1), 51–67.

Evans, D., & Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Developing a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 868–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002

Fattore, T., Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2007). Children’s conceptualisation(s) of their well-being. Social Indicators Research, 80, 5–29.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9036-7

Goldbeck, L., Schmitz, T. G., Nesier, T., Herschbach, P., & Henrich, G. (2007). Life satisfaction decreases during adolescence. Quality of Life Research, 16, 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9205-5

González-Carrasco, M., Casas, F., Malo, S., Viñas, F., & Dinisman, T. (2017). Changes with age in subjective well-being through the adolescent years: Differences by gender. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9717-1

Goswami, H. (2014). Children’s subjective well-being: Socio-demographic characteristics and personality. Child Indicators Research, 7, 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9205-7

Hallam, W. T., Olsson, C. A., O’Connor, M., J Happiness Stud, et al. (2014). Association between adolescent Eudaimonic Behaviours and emotional competence in young adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(5), 1165–1117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9469-0

Huebner, E. S., Seligson, J. L., Valois, R. F., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). A review of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Social Indicators Research, 79, 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-5395-9

Kaplowitz, M. D., & Hoehn, J. P. (2001). Do focus groups and individual interviews reveal the same information for nature resource validation? Ecological Economics, 36, 237–247.

Leung, C. Y., McBride-Chang, C., & Lai, B. P. (2004). Relations among maternal parenting style, academic competence, and life satisfaction in Chinese early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 113–143.

Liu, W., Mei, J., Tian, L. & Huebner, E. S. (2015). Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-being in school among students. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0873-1.

Malo, S., Navarro, D., & Casas, F. (2012). El uso de los medios audiovisuales en la adolescencia y su relación con el bienestar subjetivo: análisis cualitativo desde la perspectiva intergeneracional y de género. Athenea Digital, 12(3), 27–49.

Navarro, D. (2011). La participació social dels adolescents en el context escolar: Estudi psicosocial d’una experiència participativa. Doctoral thesis: University of Girona, Girona.

Navarro, D., Montserrat, C., Malo, S., González, M., Casas, F., & Crous, G. (2017). Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child & Family Social Work, 22(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12215

Neuendorf, K. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

Nic Gabhainn, S., & Sixsmith, J. (2006). Children photographing well-being: Facilitating participation in research. Children & Society, 20(4), 249–259.

Oberle, E., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Zumbo, B. D. (2011). Life satisfaction in early adolescence: Personal, neighborhood, school, family, and peer influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9599-1

Rodríguez, I. (2006). Redefiniendo el trabajo metodológico cualitativo con niños: el uso de la entrevista de grupo aplicada al estudio de la tecnología. Empiria. Revista de Metodología en Ciencias Sociales, (12), 65–88.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

September, R., & Savahl, S. (2009). Children’s perspectives of child well-being. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 21(1), 23–40.

Singh, K., Ruch, W., & Junnarkar, M. (2015). Effect of the demographic variables and psychometric properties of the personal well-being index for school children in India. Child Indicators Research, 8, 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9264-4

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research, 78, 179–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-8208-2

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). The subjective wellbeing of Australian high-school students: Validating the personal well-being index-school children. Social Indicators Research, 101(3), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9668-6

Viñas, F., González, M., Malo, S., García, Y., & Casas, F. (2014). Temperament and personal wellbeing in a sample of 12 to 16 year-old adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(2), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9242-x

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) as part of the National Research Project Programme, within the 6th National Plan for Scientific Research, Development and Technological Innovation 2008–2011, with reference PSI2010-19404. Thanks are due to Barney Griffins for editing of the English text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González-Carrasco, M., Vaqué, C., Malo, S. et al. A Qualitative Longitudinal Study on the Well-Being of Children and Adolescents. Child Ind Res 12, 479–499 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9534-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9534-7