Abstract

Bangladesh has a long history of, and substantial expertise in, managing response to Climate Variability and Natural Disasters pre-dating the emergence of Climate Change as a policy arena. Climate Change response in Bangladesh is a complex, multi-sector, multi-stakeholder undertaking that budgets and spends around US$1 billion per year through Government and Donor funding. In 2012 the General Economics Division (GED) of the Planning Commission, sponsored by the UNDP and UNEP, commissioned and undertook a Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (CPEIR) with the objective of analysing this spend, its policy and strategic drivers, the institutions delivering it and sought ways how this could be managed more effectively. The study revealed the key conclusions based on the review and identified that the government is the main funder of the Public Sector response to Climate Change and climate sensitive activity with around 75 % of funding coming from domestic sources on an annual basis. The government response is firmly embedded in existing institutions and policy frameworks and there are a number of new mechanisms being established by both Donors and Government which have yet to deliver substantial numbers and values of expenditure. There is evidence of that Climate Change Strategy has not fully penetrated the sector policy drivers of budget execution resulting in a need for improved co-ordination and profile mechanisms at Central Ministry level. There is an extraordinarily diverse range of administrative agencies involved in budget execution of climate sensitive expenditure. There is evidence that duplication and omission of activity are significant risks to the optimisation of climate response due to the diversity of institutions involved. A “gearing effect” may be evident within funding climate change actions in Bangladesh. It was noted that an increase of 11 % in donor commitments and an 18 % increase in Government commitments occurred simultaneously. It may be that there is causation between the two. The CPEIR study recommended that the way forward in Bangladesh is to introduce greater rationality in establishing the economic position and impacts of government expenditure through a macro-economic study with a view to identifying private sector partnerships in climate response, establish medium and long term costed response plans for incorporation into budgets, clarify intuitional mandates with a view to developing appropriate specialisation in climate response, and strengthen existing (and beleaguered) government co-ordination, resource allocation, monitoring and classification arrangements in Planning and Finance.

Bangladesh has a long history of, and substantial expertise in, managing response to Climate Variability and Natural Disasters pre-dating the emergence of Climate Change as a policy arena. Climate Change response in Bangladesh is a complex, multi-sector, multi-stakeholder undertaking that budgets and spends around US$1 billion per year through Government and Donor funding. In 2012 the General Economics Division (GED) of the Planning Commission, sponsored by the UNDP and UNEP, commissioned and undertook a Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (CPEIR) with the objective of analysing this spend, its policy and strategic drivers, the institutions delivering it and sought ways how this could be managed more effectively. The study revealed the key conclusions based on the review and identified that the government is the main funder of the Public Sector response to Climate Change and climate sensitive activity with around 75 % of funding coming from domestic sources on an annual basis. The government response is firmly embedded in existing institutions and policy frameworks and there are a number of new mechanisms being established by both Donors and Government which have yet to deliver substantial numbers and values of expenditure. There is evidence of that Climate Change Strategy has not fully penetrated the sector policy drivers of budget execution resulting in a need for improved co-ordination and profile mechanisms at Central Ministry level. There is an extraordinarily diverse range of administrative agencies involved in budget execution of climate sensitive expenditure. There is evidence that duplication and omission of activity are significant risks to the optimisation of climate response due to the diversity of institutions involved. A “gearing effect” may be evident within funding climate change actions in Bangladesh. It was noted that an increase of 11 % in donor commitments and an 18 % increase in Government commitments occurred simultaneously. It may be that there is causation between the two. The CPEIR study recommended that the way forward in Bangladesh is to introduce greater rationality in establishing the economic position and impacts of government expenditure through a macro-economic study with a view to identifying private sector partnerships in climate response, establish medium and long term costed response plans for incorporation into budgets, clarify intuitional mandates with a view to developing appropriate specialisation in climate response, and strengthen existing (and beleaguered) government co-ordination, resource allocation, monitoring and classification arrangements in Planning and Finance.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Climate Public Expenditure Review

This Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review (CPEIR) is an analysis of the policy, institutional and financial management arrangements of the agencies involved in climate sensitive activity in Bangladesh focused mainly on Government—both central and local government. The analysis is done based on an adopted methodology to identify and assess the financial scale of climate sensitive activity carried out by the Government. This methodology was applied to generate initial indicative figures and analysis of budgets and spend from the past 3 financial years. The figures were set in a national context by comparing the budgets and spend to both GDP and the Government budget as a whole. Public Financial Management systems were also reviewed (World Bank 2010a, b, c). Analyses of the international arrangements for financing climate actions, the current roles of NGOs, the private sector and households in Bangladesh were also considered.

In summary, the CPEIR comprised an assessment of current policy priorities and strategies as these relate to climate change at national and local levels, a review of the institutional arrangements for promoting the integration of climate change policy priorities into budgeting and expenditure management, and a review of the integration of climate change objectives within the budgetary process including as part of budget planning, implementation, expenditure management and financing.

1.1 Challenges of Public Expenditure Review for Climate Change

Climate change itself is not easy to define for economic or financial assessment and it is also a relatively new entrant to the public policy arena. Identification of spend is therefore the first challenge. There are two distinct aspects to this challenge.

Firstly, there is no functional classification in the standard of classification for expenditure (COFOG in GFSM 2001) therefore it is easy to be drawn to an administrative approach to identifying climate spend—that is, an approach based on which administrative unit spends money (IMF 2001, 2011). This limitation was exposed by the cross cutting and diverse nature of the response to climate issues ranging from hard adaptation capital works to socially based protection, livelihoods and health programmes that form the adaptation strategies of government. The term “climate” rarely features in the descriptions of administrative units responsible for delivering adaptations (Asian Tiger Capital Partners 2010; Ayers et al. 2009; Burton 2004).

Secondly, the separation of climate sensitive spend and climate change spend is a qualitative and judgment-led exercise and is open to refinement and constructive criticism. Equally, there is valid debates to be conducted on the separate classification of climate resilience spend, from development deficit spend and which element of expenditure addresses each component (Hedger 2011; Haque 2009).

These are complex matters which at this stage of analysis of climate sensitive spend that arise because climate response and therefore climate change expertise is firmly embedded, on the whole, in existing institutions, activities and policy frameworks, but is not always explicitly recognised as such. This could be, however, regarded as a rational state of affairs as charging technically able, legally mandated national experts (all other things being equal) with managing response is most likely to result in the most effective outcomes (Tanner and Mitchell 2008; Stadelmann et al. 2010).

The study, as an initial rather than a definitive snapshot, expressed the hope that it would contribute to the framing and identifying future research. The methodology developed in the study is a first step in what is expected to be an ongoing process of refinement, review and evaluation of climate expenditure in Bangladesh and elsewhere.

1.2 Defining Climate Change

The definition of climate finance used in the CPEIR recognised that resilience to the effects of both climate and climate change is a multi dimensional activity—as outlined in the BCCSAP. In reviewing the climate sensitive budgets and expenditure, it was found that the scale, range and diversity of both budgets and the agencies involved in delivering activities that contribute to intended climate resilient outcomes for Bangladesh tends to suggest that developing a single definition would be a complex task (Alam et al. 2011; CCC 2007; COWI and IIED 2009; DMB 2010; DMRD 2008, 2010; GED 2010; GoB 2008; Hedger 2011; Huq and Rabbani 2011).

In conducting the analysis a working definition of Climate Sensitive expenditure was used that was based broadly on the OECD definition shown in Table 19.1. Defining Climate Change and related specifically to climate variables and impacts and how the government has responded to this. In essence the working definition used is based on the identification of adaptation activity with a linkage to the Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (BCCSAP) and its policy themes.

It should be noted that the analysis focused on the policy interventions needed for climate change adaptation, recognising the current priority in Government of Bangladesh (GoB) approaches to climate change (Huq and Rabbani 2011; Hedger 2011). However the CPEIR does highlight the considerable sums being invested in fossil fuel power generation, thus increasing greenhouse gas emissions, although these still remain very small on a global scale. This illustrates the policy dilemma that inevitably arises when considering economic development in Bangladesh. Essentially, industry needs power to drive economic growth and to achieve this. The Government has the allocative task of deciding the relative merits and imperatives of explicitly prioritising climate adaptation, climate mitigation or growth from the limited resources available. This also points up the need to have more knowledge of the macro-economic impact of climate sensitive spend to inform the debate (Narain et al. 2011).

2 Bangladesh Context: Climate Public Expenditure Review

In the Bangladesh context, it is well known that there are many agencies involved in climate response and climate sensitive activities including central and local government, development partners, NGOs, households and the private sector. Indeed, this has been characterised in the public domain as “institutionally chaotic” However, until the CPEIR was conducted, there had been no systematic review to identify the scale of the ongoing financial commitments, the scope of institution as involved or the key policy drivers in this aspect of public expenditure.

An expressed, key long term aim for the Government of Bangladesh is to develop a Climate Fiscal Framework within which the roles, risks, and responsibilities of parties involved in climate response can be allocated and a sustainable long term funding framework built.

2.1 Financial Review

The CPEIR analysed budgets and expenditure over a 3 year period from 2008/2009 to 2011/2012. The main focus was on the government budget. Among other matters the study reviewed the overall allocation of resources, the mechanisms delivering climate finance, the financing of climate spend, the main agencies involved, their processes and the nature of the budgets and the spend delivered. A methodology was also developed to identify climate finance within the Government budget. The methodology relied on qualitative and ultimately subjective judgements of spend as no universal international definition of climate change spend exists within COFOG or definitely elsewhere. This approach produced an indicative outcome in absolute terms and a similarly indicative, although informative, analysis of spend and climate actions undertaken by the government. The methodology was new and undoubtedly capable of further refinement under the scrutiny and evaluation of a wider audience. It is to be hoped that the study will form part of a dynamic process contributing to greater understanding and effectiveness of a climate response in Bangladesh (CPD 2008).

The CPEIR in Bangladesh compellingly demonstrates that climate change is a substantial, cross cutting, multi sectoral activity and that, comparing the response in Bangladesh with that of other countries is currently difficult as the precise definition and framework for each country is largely determined by that country. From a Government perspective—as perhaps evidenced by the institutional allocation of responsibility—the main issue is to deliver climate resilient development, covering current climate variability and climate change.

Amongst the important lessons learned from the review of budgets and expenditure is that expenditure typically contributes to more than a single outcome, often perceived as being readily identifiable by primary and other purposes. This was particularly evident in respect of Social Protection Schemes (BCCSAP Theme 1) where it was found that determining the climate and climate change-attributable element of these strategic initiatives was very much a matter of both perception and qualitative, informed but ultimately subjective judgements. This is also evident in physical adaptation work, for example, where the incremental or marginal expenditure relating to a change in climate is inextricably bound together with the design and implementation of the adaptation as a whole. The purpose of such activities will contribute to a number of outcomes including climate change resilience (BSS 2011, 2012).

This facet of identifying specific and singular climate change budgets and separating these from budgets intended to achieve other outcomes such as response to disasters as well as climate resilience would require a level of sophistication in budget classification and cost allocation that would perhaps elude most countries in the world and would certainly require substantial development of systems and capacity to achieve. It was found, however, in Bangladesh that substantial progress has been made in recent years in financial accounting and that financial data on a code by code basis over a number of years was readily available in flexible, specifiable formats for analysis (IMF 2011).

It should also be considered in the Bangladesh context that GoB has implemented many policies for climate variability and disaster risk management for many years and this activity pre-dates the emergence of climate change as an issue. These activities have contributed to strengthening the country’s response to climate change concerns. This has, perhaps inevitably and for sound operational reasons, led to the situation where climate change budgets and expenditure are integrated with and integral to existing historical activity and institutions and cannot readily be separated from this. With this background in mind the main findings, conclusions and recommendations from the financial review the major findings are set out below.

Based on the methodology used in the study it is estimated that the Government of Bangladesh typically spend around 6–7 % of its annual combined (development and non-development) budget on climate sensitive activity. This equates to an annual sum in the region of US$1 billion at current exchange rates. This sum is utilised to address all six themes within the BCCSAP. However it is noted that whilst the spend on climate sensitive activity increased from 6.6 % to 7.2 % between 2009/2010 and 2010/2011, it fell back to 5.5 % of budget in 2011/2012.

This level of expenditure represents something in the region of 1.1 % of GDP on an annual basis. The financing of the annual spend is largely funded from domestic resources. Over the period 2009/2010 to 2011/2012 the funding of climate sensitive budgets has been of the order of 77 % from domestic resources and 23 % from foreign donor resources. This is broadly in line with overall funding of GoB expenditure (development and non development) overall which is funded approximately 80 % by domestic resources.

There has been a marked shift in the donor resources funding climate sensitive budgets in recent years from grants based to loans based. Loan funding increased from 58 % to 82 % of foreign resources between the 2009/2010 and 2011/2012 programmes. It was found that approximately 97 % of spend attributable to climate sensitive activities was for climate adaptation as classified under the BCCSAP themes ranging from infrastructure to social protection.

In absolute terms, the level of climate sensitive budget rose between 2009/2010 and 2011/2012, however, between 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 the absolute level of spend reduced. It seems likely that this was due to resources being diverted to energy and transport through the ADP. This presents a climate change dilemma for Bangladesh as the recently developed energy policy sets out to address the present reliance on Natural Gas for by increasing usage of fossil fuel as well as renewable sources. Bangladesh has significant quantities of high quality coal reserves and is presently developing a National Coal Policy (MoPEMR 2011; The Daily Star 2011).

An increase in overall climate related commitments by 16 % between 2009/2010 and 2011/2012 was driven by the non-development budget which is 100 % financed by GoB. GoB commitments increased by 18 % in the period whilst foreign resources increased by 11 %. This may be termed, in practice, a “gearing effect” at the macro level whereby increases in donor funding (specifically for the climate change element) have been met by a GoB increase in overall climate sensitive spend. Essentially, based on the figures in the study, a 10 % increase in donor funding delivered an outcome of 15 % increased spend in climate sensitive activities.

2.2 Public Financial Management

There are four main operational mechanisms in place to deliver climate sensitive spend at the time of writing. These are non development budget, annual development programme (ADP), Bangladesh Climate Change Trust Fund (BCCTF) with government funds, and Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund (BCCRF) with donor funds (Polycarp 2010; GoB 2008).

All operational funding mechanisms address all six themes in the BCCSAP, albeit some specialisation was noted in that the non-development budget funds a larger proportion of the Social Protection theme and the ADP funds a greater proportion of infrastructure adaptation. This may be expected, given the capital intensive nature of infrastructure expenditure. However, perhaps the main point of concern is the risk of gaps and overlaps arising within what is a significant and complex annual undertaking. A further financing facility [Strategic Programme on Climate Resilience (SPCR)/Pilot Programme on Climate Resilience (PPCR)] is also coming on-stream in the near future thereby creating further risk of both “gap and overlap”. Given this, there is a clear case for addressing co-ordination at the technical, financial and planning levels and perhaps even a case, after due consideration, for specialisation of funding streams.

It was found that most of the climate sensitive spend delivered is within multi-dimensional, strategic programmes, including the Agricultural Subsidy and Social Protection Programmes which are substantially funded through the non development budget. The study used a scale of direct relevance from “direct” or concrete adaptation through to implicitly relevant programmes on a scale of 1–4—i.e. implicitly or somewhat relevant. Around 70 % of the budget and spend was found to be within the level 3 and 4 programmes. Three things came out as a indicative to the public finance management.

Existing programmes, institutional and budget architecture are being utilised by the government to deliver climate sensitive activity, including responses to climate change. This is perhaps unsurprising given Bangladesh’s long experience and accumulated expertise of response to climate variability and natural disaster. The separation of the climate change element of these programmes is a subjective and judgmental task given the evident integration of climate sensitive policy, institutions and budgets with pre-existing climate related structures in the Government systems. In terms of strengthening institutions through technical assistance and thereby supporting the delivery of climate sensitive spend, there is a clear case for focussing on country systems as this is where the most significant element of ongoing climate response, on a financial technical and experience basis, is located.

The process through which the national budget is prepared, placed and passed in the Parliament could be strengthened from a climate perspective given the scale of expenditure and budgets in the activity.

All line ministries/divisions of GoB have already been brought under the coverage of MTBF, which is a multi-year approach to budgeting so as to link spending plans of the government to its policy objectives. The MTBF seems to be a step forward in the sense that it allows the line ministries to plan ahead. However, it has quite a long way to go, at least in regard to climate change aspects. Ministry spend is driven by sector policy rather than climate strategy and there was evidence that substantial adaptation expenditure, particularly of capital works in Local Government, did not appear to reference Climate Change as a policy driver in the Ministry Budget Framework. The integrated Budgeting and Accounting System (iBAS) has the flexibility to add new functionalities to capture monitoring and evaluation information.

2.3 Policy Review

The study reviewed national and international policy and strategy in respect of climate change, but also reviewed sector policy in key areas of government activity that influence the government’s response to climate change. The policy review used a framework that recognised supportive, non-supportive and neutral policy on a sectoral basis and also a review of direct climate change policy.

Climate change policy operates in a competitive policy environment in Bangladesh. The government’s priorities at this time include energy and transport which are key drivers of economic growth (Finance Division 2009, 2011; The Daily Star 2011). A brief review of energy and power policy revealed a dilemma for the country in that the reliance on dwindling stocks of natural gas, which is used for about 80–90 % of electricity generation is planned to be replaced by a significant increase in the use of coal as well as renewables. It is understood that National Coal Policy is currently being developed. With its historical experience of vulnerability to weather disasters, Bangladesh has taken several steps in recent years to embed climate change in national policy making. However whilst climate change policy is a new element in national policy and development partner support, it is being framed within the broader policy contexts relating to development and response to disasters. This means that sectoral policy rather than climate change strategy is most prominent in driving government spend in some key spending ministries. It remains a concern that climate related strategy is not effectively transacted to policy and therefore to implementation and the attendant co-ordination architecture of accountability, performance and governance that is provided by the MTBF and the ADP.

As regards the policy and strategy making process in Bangladesh, experience so far suggests that most polices are driven by experts and bureaucrats, following a top-down process and although the participation of stakeholders has significantly increased, the quality of participation of poor people appears to have remained unsatisfactory. There is no exclusive national policy that deals with climate change in Bangladesh. The BCCSAP strategy does not specify which one, out of the 28 adaptation modalities, should be prioritised over the others and in which order the country implements such a long list of adaptation programmes. The absence of both prioritisation and costing should be addressed.

The development of climate change policy in Bangladesh has been stimulated and promoted by the international context. Reciprocally, Bangladesh has helped develop Least Developed Country (LDC) positions and particularly contributed to debates on climate finance. Bangladesh’s vulnerability in a global context has given it moral voice within the international arena and it has championed the LDCs. In the longer term, the country’s economic development may lead it into the middle income group- indeed that is a goal of political interests. This would mean it would benefit less from international climate funds (COWI and IIED 2009; UNAGF 2010).

The Government of Bangladesh led the development of the innovative Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (which included low carbon dimensions), and was an early first from an international perspective. The strategy is beginning to be the critical reference document in cross planning processes in Government and for funding mechanisms such as the BCCTF and the BCCRF. However, the document is now almost 3 years old and could perhaps be usefully revised and relaunched to ensure that high awareness levels at Ministry level are maintained and enhanced where necessary. Coupled with renewed efforts for coherent development planning, in which climate change can be embedded, the country is moving ahead on climate change.

Analysis of policy and programmes in many Ministries shows how wide and strong the connections are to climate change. Climate change impinges on the responsibilities of a wide range of Ministries although the Ministry of Environment and Forests has the technical lead. Accordingly, in recent years a large number of investments have been made by a range of Ministries, for example in coastal infrastructure and crop development which provide a base from which to improve climate resilience. The active disaster risk management agenda has been a long running focus for development, and helped put in place some local planning processes and policy transformations which help provide resilience for climate change.

2.4 Institutions Review

The institutions reviewed in this study included an international and national institutions involved in climate change in Bangladesh. This was a wide and complex constituency of interests that included central Ministries, line Ministries, local government, NGOs, the private sector and development partners.

The constituency involved in climate issues in Bangladesh is wide and diverse. The study identified 37 Ministries (plus their departments and autonomous bodies) as well as more than ten Donors on a multi lateral and bi-lateral basis, Local government, NGOs, households and private sector are also active in climate sensitive activity. This presents challenges and hazards to coherence and co-ordination.

Spurred on by direct experience of some extreme weather catastrophes, there has been increased focus on handling climate induced vulnerabilities in the light of climate change across the national political consensus. Some of the dynamism and energy has resulted in tangible outcomes with new national and sectoral policies and institutions being developed in recent years all of which included climate change concerns (OECD 2003).

Ministries such as Local Government, Agriculture, Social Welfare, Water Resources, Food and Disaster Management have climate change components and mandates. These Ministries receive funds to implement programs through the Annual Development Plan (ADP) and non-development budgets. The Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) has the mandate to implement projects from the BCCTF and BCCRF. Therefore, there remains a tension among the Ministries over climate change related issues owing to the tension that exists between the development of policy and the differences in budget between institutions. This situation makes the case for clarification and specialisation of institutional mandates and for strengthening allocative processes within the MTBF and ADP (Haque 2009; Hedger 2011).

The lack of intra-government coordination mechanisms is a limitation. The bureaucracy appears to have hindered progress in this regard which points towards a real imperative in developing these co-ordination mechanisms. The study identified three aspects of co-ordination within Government which are worth to illustrate a bit.

Policy Co-ordination is a key area of expected sets of coordination. We understand this policy coordination as the achievement of balanced influence between sector policy and climate change policy given the evident level of integration of climate change and climate in the delivery of services. Both sectoral policy and the national climate change strategy have influence and thus must be adequately balanced. This is the role of Planning Commission.

Technical Co-ordination is also an important aspect of desired coordination and this role lies with MoEF at the moment and has evolved from an environmental mandate. However, large elements of the climate response in Bangladesh at this stage relate to adaptation strategies led by other Ministries ranging from infrastructure to social protection programmes as well as a strong link to disaster risk reduction (DRR) (DMB 2010; DMRD 2008, 2010; Zakir 2011).

Financial and Performance Co-ordination is critical to get success in whole of effectiveness in climate finance in Bangladesh. This role lies with Finance Division and is implemented via the MTBF which acts as a governance and performance management mechanism as well as matching resources to policy. Also, if the proliferation of funding sources is taken into account—at least five were identified—Finance Division has a crucial role in the co-ordination of funding.

The interface between each coordination function takes on crucial and central importance. This is an obvious and desirable need to improve the flow of funds and to ensure that climate change is reflected properly in implementation. There are mutual interfaces between all three coordination functions, between Finance Division and Planning Commission in the funding of the ADP, between Planning Commission and MoEF in the development of policy and between Finance Division and MoEF through implementation of the MTBF. Currently, the main responsibility to foster adaptation lies with the lead institution, Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF). Unfortunately, its performance so far appears to have been limited for many reasons, such as weak structure, duality in mandate, lack of manpower and trained human resources and weak legal framework. It is argued that the MoEF has neither a clear legal mandate as yet, nor specific Rules of Business to lead all the activities centred on climate change in the country (GED 2010).

It is encouraging to note that the NGOs of Bangladesh have been playing an important role in reducing climate change induced hazards. Some of the NGOs are engaged in massive public awareness campaign including preparedness training on climate change and sea-level rise and their impacts. Nevertheless, their efforts are not properly reflected in national programmes. A substantial portion of donors’ assistance is channelled through NGOs. However, “they operate completely outside the Joint Country Strategy (JCS) framework, leaving scope for potential overlap and duplication with the development programmes of the government”. There is also insufficient capacity of local bodies to plan and manage climate related projects continues to remain a major challenge to improve on climate vulnerability. In addition to intra-government co-ordination, the co-ordination between institutions i.e. national, regional and local governments would appear to be quite limited, undermining the effectiveness of the results that the project outcomes are designed to achieve. This is perhaps most sharply illustrated by the absence of climate change references in the MBF of Local Government.

The involvement of the private sector is at its initial stage, and offers a lot of potential opportunities. Bangladesh has not yet formulated a policy in relation to private sector involvement in climate change and has not set any target of preferred mix of public and private funding or delivery modalities. This must be considered more fully in the development of a National Climate Fiscal Framework Development partners and Government have separated climate funding from mainstream Government planning and expenditure for their separate reasons. On the Government side the grounds are that current processes of assessment within the Planning Commission are slow and would delay spending. The functioning of Local Consultative Group on Environment and Climate Change is yet to gain momentum.

2.5 Local Government Review

The adaptation component of the climate change agenda is a familiar one for many in Bangladesh. While, local stakeholders are not always able to distinguish between development expenditure and climate related expenditure, experiences of flooding, cyclones and other climate related impacts have raised significant awareness of the challenges that Bangladesh faces. In general, local stakeholders identified climate impacts as cyclones, deforestation, tidal surge, salinity, water logging, flooding and drought. The effects on people’s daily lives include loss of livelihoods, ground water depletion, irrigation problems, health problems and limited access to schools and health facilities. However, less is known by these local stakeholders about the causes of climate change and the need for mitigation.

The two most popular strategies for addressing climate change identified by local stakeholders is infrastructure development and sustainable and alternative livelihoods, and that capacity building is necessary to enable people to work and development solutions to address climate impacts. However, this does not support the findings that a large proportion of central government funds, and some donor funds, are already allocated to Union Parishads (UPs) to implement infrastructure development (LGD 1998, 2009a, b).

There are several sources of climate related finance found at the local level: central government funds, donor funds, private sector donations, household spending and local government internally generated revenue. On average, 14 % of the UPs and Pourashavas’ budgets are sensitive to climate change. Of this, the budgets of UPs and Pourashavas in coastal regions spend more than those from the floodplains and Barind. Of the schemes that UPs and Pourashavas deliver, safety net schemes, such as 100 day employment scheme, have a high sensitivity to climate change, of around 48–50 %. While both ADP and Local Government Support Project (LSGP)/Local Government Support Project Learning and Innovation Component (LGSP LIC) have similar sensitivity to climate change, between 11 % and 13 %, LGSP/LGSP LIC is made up of a larger amount of money and therefore able to make a larger contribution to addressing climate change (Deopara Union Parishad 2011; Gabura Union Parishad 2011; Garoukhali Union Parishad 2011; Kunder Char Union Parishad 2011; Lata Union Parishad 2011; Padmapukur Union Parishad 2011; Paler Char Union Parishad 2011; Rishikul Union Parishad 2011).

In addition to these funds, household and individual’s spend their own financial resources on addressing climate change impacts. Most damages exceed poor households’ income, although some financial and non-financial support is provided from either government, donors or NGOs, such as rice and accommodation. While the richer and middle income groups have more resources to reduce damages from climate impacts, ill-preparedness to the increased frequency of extreme weather events and limited government, donor and NGO support could push them into poverty over time.

Central government funds are usually allocated to Zilas and Upazilas for further allocation to UPs. Some donor funds use the national system to channel funds to UPs, such as LGSP/LGSP LIC, but most channel funds directly to NGOs that bypasses the government system. The effectiveness of donor funds are yet to be assessed but their accountability frameworks are wide-ranging and complex. One aspect that is consistent in many of the funding mechanisms is the limited involvement of, or autonomy for, UPs in the planning and budgeting of these funds. UPs have limited power, financial autonomy and capacity to address climate change. Local planning and budgeting is a linear operational process whereby UPs implement the directives of central government and follow guidelines set by Upazila administrative offices (The Daily Star 2010). Moreover, there is a disconnect between national and local government bodies, and a strained relationship between local administrative offices and local elected bodies. Questions are raised as to whether UPs are equipped and well positioned to implement large scale climate related projects that requires the management of large volumes of funding and coordination with a range of national and local bodies.

Finally, NGOs play a significant role in Bangladesh, including the delivery of climate related finance. They play an important and added value role in the area of mobilizing and engaging communities, providing technical expertise and ensuring transparency of expenditure. However, the lack of coordination with local government bodies and competition between NGOs present a challenge in tracking climate expenditure and aligning efforts to addressing climate change in a more integrated manner.

3 Looking Ahead: Way Forward

There are established planning and allocation mechanisms within Government that, with strengthening, can bring improved co-ordination, allocative efficiency and consequently better outcomes to climate issues in Bangladesh. The creation of alternative mechanisms will add further complexity to a substantial undertaking in Bangladesh that already utilises considerable domestic resources. Climate issues in Bangladesh are a matter of national interest from both a physical implementation and financial and economic perspectives. In summary therefore, it is recommended that the next stage in the process for Bangladesh should focus on three main initiatives in respect of Climate funding.

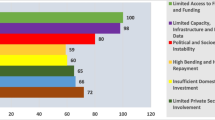

The government should be supported to ensure balance the policy influences at play in climate and the wider policy arena by strengthening of existing country architecture, strengthen and utilise existing, established Government planning and financial allocation mechanisms of the MTBF and the ADP to manage climate funds and to manage results through a strengthened performance management arrangements within the MTBF and at the institutional level. Accordingly, a total of 20 recommendations are set out below for consideration. An indicative sequence is shown in diagrammatic format at Fig. 19.1: Indicative Sequencing of Next Stage Recommendations.

3.1 Climate Strategy

In relation to have a right climate strategy, some consideration should be given to a further review of the BCCSAP in the near future to ensure that it remains fully relevant to current circumstances. Further consideration should be given to including more detailed costing of the needs of Bangladesh in respect of climate and climate change to provide a cornerstone for the development of a Climate Fiscal Framework. This revision should take into account the potential role, risks and responsibilities of the private sector (including households) in respect of climate change with the intention of engaging the interest, resources, skills and knowledge available in that sector of the economy.

3.2 Public Finance Management

In public financial management, the development of a national climate fiscal framework is a high priority to ensure allocative efficiency and effective transaction of strategy to both policy and budgets. The framework should recognise some of the critical factors: the risks, roles and responsibilities that should be allocated to each institutional sector within Bangladesh including central government, local government, donors, NGOs, households and the private sector; the allocation of funding responsibilities to all aspects of climate finance and activity; the need for a focal point financial framework that ensures the long term sustainability of funding streams; ensuring that long terms plans in a revised and costed BCCSAP can be funded or prioritised for funding on a rational basis within a climate fiscal framework; the capacity on human resources (HR) and institutional basis to implement the framework on a sustainable and achievable basis.

The current level of expenditure on climate sensitive activity, around US$1 billion per year, is significant in economic terms. It was noted in BCCSAP that a study of the long term macroeconomics of climate [Thematic area 4; Programme 5 (T4P5)] was recommended, but this has not yet been conducted. This study should be conducted as soon as possible to support the development of a climate fiscal framework and should address, inter alia, considering an evaluation of the economic impacts of not spending at the current levels, an evaluation of the economic development effects of the current expenditure, including the effects at household level, an evaluation of the potential long term funding streams for financing climate change activity, including the feasibility of hypothecated taxation and potential of donor sources, an evaluation of the sustainability of the current and required long term spend on climate change and climate sensitive activity, the relationship between the government’s energy and transport policies and climate policy in the longer term with a view to achieving a balanced accommodation of each priority.

It is recognised that the GFSM 2001 does not include a functional classification for climate change. However, it would be a useful development for the Government if some functional (or policy) recognition of climate change, perhaps on a thematic basis according to BCCSAP themes, could be incorporated into the structure of the Chart of Accounts presently under revision.

There are presently five mechanisms delivering climate finance in Bangladesh and as each addresses all six themes in BCCSAP some consideration should be given to a review of the co-ordination of this funding activity. There is a case for explicit recognition of the appropriateness of the use of each funding mechanism for particular thematic purposes, as would appear to be the case with the ADP contributing high volumes of the planned expenditure on infrastructure. The mandates and intended roles of each funding source should therefore be established with a view to eliminating the risk of gaps and overlaps. This may also have the benefit of further developing specialist skills and knowledge in particular aspects of climate spend and activity.

It was noted that each finance delivery mechanism within the government system operates to different levels of efficiency in respect of delivering spend. Typically, for example, the ADP tends to underspend by a greater amount than the non-development budget. It is therefore recommended that some consideration is given to funding capacity building public financial management initiatives with the objective of ensuring equality of process-efficiency across the climate finance delivery mechanisms.

Guidelines for the award of funding of climate change related projects proposed by both government and non-government entities to the BCCTF should be developed immediately to maximize the utilization of limited resources allocated to BCCTF. The development of procedures for the BCCTF should also include a clear statement of the role of the Controller and Auditor General in respect of the fund. The activity of the BCCTF should also be reflected in the MTBF and MBF of the Ministries with a view to accommodating the need for performance and accountability in respect of fund expenditure.

In respect of the BCCRF and BCCTF some consideration should be given to integrating the funds with existing key country systems, whilst retaining their intended flexibility and agility of response. As a parallel initiative strengthening of these key country systems (MTBF and ADP in particular) would seem to be an effective long term strategy with wider benefits than the impacts on climate change response alone. In particular, the BCCRF should give serious consideration to funding institutional strengthening activities, including the reduction of fiduciary risk, as a key strategy in improving co-ordination of climate sensitive activity.

Some capacity building activity should be considered for the Controller and Auditor General’s Office to enable him to address climate funding issues in the forthcoming audit plan and in particular to review climate finance in the forthcoming planned and regularity performance audits. A review of procurement regulations to incorporate climate sensitivity should be considered for the Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU).

3.3 Climate Policy and Planning

In relation to Climate Policy and Planning, Ministry Budget Frameworks presently do not always identify climate and change activity. Some consideration should be given by the Finance Division to the inclusion of a climate change dimension or “marker” to the MTBF procedures to ensure that the activity is fully recognised by line Ministry accountability, performance management and governance structures. Such an initiative was successfully implemented by the Finance Division in respect of gender and poverty in recent years.

Consideration should be given to strengthening key relationships and co-ordination processes in the development and implementation of climate policy. In particular, three aspects should be focussed upon the transaction of strategy to implementation via sector policy should be addressed by ensuring that the climate dimension is adequately addressed at sectoral level. This must involve setting a climate dimension or marker within the MTBF process to identify budgets, promote accountability and, generally, match expenditure and performance plans with climate policy. It should also involve standards and guidelines, established by the Planning Commission, to ensure that the climate dimension is considered in all policy development. Some consideration should be given also to creating a climate marker within the ADP.

The relationship between, and respective capacities of, the Planning Commission and Finance Division in interpreting and funding climate policy should be strengthened to ensure appropriate allocative efficiency of resources and consistency with policy and priority intentions. The communication of climate change strategy to line Ministry level and on to department, autonomous body and local government level should be a priority to ensure adequate reflection within Ministry budget frameworks.

3.4 Climate Institutions

The institutional mandates in respect of the three aspects of co-ordination identified in the study (technical, policy and financial/performance) should be clarified and steps taken to strengthen these and the interfaces between them. This should involve specific cross-institution actions involving Planning Commission, Finance Division, MoEF, DRR, Local Government Division and other institutions within government that make a significant contribution to climate sensitive activity.

There is also a case for strengthening the co-ordination and transaction of climate policy, finance and delivery between the levels of government and the various non-government institutions, including the private sector, involved in climate change in Bangladesh. It is also important that the private sector and civil society organizations create more inclusive partnerships so that all their efforts are coherent and have greater impact on reducing climate vulnerability. Existing institutions that could potentially be developed in this regard could include the Ministry of Industry and the NGO Bureau.

The National Parliamentary Standing Committee on Environment should be empowered so that the body, with its legal authority, can oversee and guide various activities related to climate change, including involvement in international negotiations for adaptation. They may be actively involved in mainstreaming adaptation while sectoral allocations and priorities are made for the annual development plan. There is a case for a programme to be delivered in this area as a means of engaging the Committee and developing political leadership on climate issues. This initiative should also consider the formation of a function, perhaps a standing committee, to scrutinize projects/expenditure proposals regarding climate change related activities before placement of the overall budget. This would perhaps be a valuable programme for funding by the BCCRF as support for political level engagement and leadership.

As regards knowledge management, academic and research bodies and universities should give more efforts toward facilitating generation of information and knowledge related to climate change and its impact as it is widely acknowledged that long term studies on the effects of climate change are necessary. This was a particular limitation of the CPEIR in that only three historic years were considered to give an initial snapshot and trend in respect of funding and spend.

The BMCs and Climate Change Cells of line ministries should be equipped by personnel with expertise in the area of climate activities. Such a development could be considered for funding under the capacity building theme of BCCSAP. On the basis of strengthening institutional memory and business continuity, some consideration should be given to establishing a critical mass or group of climate specialists within government who have a portable set of skills that may be relevant to a number of Ministries involved in climate response. This recommendation is distinct from the administratively based creation of climate change cells or a climate change unit in the MoEF and focuses more directly on the HR requirements to equip both Climate Cells and BMCs with the necessary skills to establish performance evaluation and monitoring skills relevant to the cross cutting and pervasive nature of climate response in the Government of Bangladesh. It is clear that to be workable, such an initiative would require a good level of engagement with the Public Service Commission/Ministry of Establishment to ascertain both its feasibility and scope. It is also clear that such a group would require a diverse range of policy and operational skills given the diversity of professional disciplines involved in the climate response.

As a step towards bridging relationships between different local stakeholders by highlighting each of their strengths and weaknesses in delivering climate finance, the conduct of an appraisal of the capacity and comparative advantages of different local stakeholders to manage larger scale projects should be undertaken. For example, while UPs should be involved in climate related project, they may not be equipped with the capacity and resources to take on certain roles such as overall supervision and monitoring and evaluation of large scale projects. It may be that local administrative offices and NGOs should utilize their expertise in financial management, technical support, supervision and monitoring of climate finance, and local elected bodies should be equipped with necessary power and capacity to plan, budget and manage programs using a participatory approach.

Building on the existing vulnerability mapping database used for safety net programs, there is an urgent need to conduct further empirical and robust assessments of household spending on climate change related activities. This information could help target and prioritize funding to address the needs of households that are spending a large proportion of their income on addressing climate impacts. While there is a need to safeguard those most vulnerable, there is also a need advocate preventative measures to those with high- or middle- levels of income from slipping into poverty as a result of climate impacts.

3.5 Non Government Organisations and the Private Sector

Given the time constraints and scale of activity in climate issues in Bangladesh, it is felt that insufficient analysis was conducted in respect of both NGOs and the private sector. It is therefore recommended that a review or survey study is conducted in respect of climate sensitive activity in these economic sectors. The study should focus on the sources and application of finance and the policy and strategy architecture that frames spend.

References

Alam K, Shamsuddoha M, Tanner T, Sultana M, Huq MJ, Kabir SS (2011) Planning exceptionalism? Political economy of climate resilient development in Bangladesh. In: Understanding the political economy of low carbon and climate resilient development. Institute of Development Studies

Asian Tiger Capital Partners (2010) A strategy to engage the private sector in climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Prepared for the International Finance Corporation

Ayres J, Alam M, Huq S (2009) Adaptation in Bangladesh. In: Tiempo: a bulletin on climate and adaptation, p 72

Bhattacharya D (2010) Graduating from the LDC Status: the ‘high’ and the ‘long’ jump of Bangladesh. In: Presentation to the International Dialogue on exploring a new global partnership for the LDCs in the context of the UNLD IV, Dhaka, 24–26 November 2010

BMDA (2012) Barind Integrated Area Development Project Report. Barind Multi-purpose Development Authority (BMDA). Ministry of Agriculture. www.bmda.gov.bd

BSS (2011) BCCTF approves six projects. Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS). http://news1.bssnews.net/newsDetails.php?cat=107&id=209756&date=2011-11-23. Dated 23 Nov 2011

BSS (2012) Trustee Board on climate change okays 5 projects worth Taka 97 crore. Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS). http://news1.bssnews.net/newsDetails.php?cat=107&id=209756&date=2011-11-23. Dated 25 Jan 2012

Burton I (2004) Climate change and the adaptation deficit. Occasional Paper – 1, Adaptation and Impacts Research Group (AIRG), Meteorological Service of Canada, Environment Canada, Downsview

CCC (2007) Bangladesh must participate meaningfully and effectively in international processes to work out a viable and equitable future climate regime. Climate Change Cell (CCC), Department of Environment, Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of Bangladesh

COWI and IIED (2009) Evaluation of the operation of the Least Developed Countries Fund for adaptation to climate change. GEF Evaluation Office and Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Evaluation Department Government of Denmark. http://www.evaluation.dk

CPD (2008) Accra Conference on aid effectiveness: perspectives from Bangladesh. CPD Occasional paper Series, paper 76, Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Dhaka. url:http://www.eaber.org/sites/default/files/documents/CPD_Rahman_2008_02.pdf

CPD (2008) State of Bangladesh Economy in FY2007-8 and Some Early Signals Regarding FY2008-09 (First Reading). CPD IRBD Team, paper 70, Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), Dhaka

Deopara Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Deopara, Dhaka

DMB (2010) National Plan for Disaster Management (NPDM) 2008–2015. Disaster Management Bureau (DMB), Disaster Management and Relief Division (DMRD), Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

DMRD (2008) Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (Phase I). Disaster Management and Relief Division (DMRD), Ministry of Food and Disaster, Government of Bangladesh. http://www.cdmp.org.bd/

DMRD (2010) Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (Phase II). Disaster Management and Relief Division (DMRD), Ministry of Food and Disaster, Government of Bangladesh. http://www.cdmp.org.bd/

Finance Division (2009) Towards revamping power and energy sector: a road map. Ministry of Finance Government of Bangladesh

Finance Division (2011) Power and energy sector road map: an update. Ministry of Finance (MoF). Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka. www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/3431.pdf

Gabura Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Gabura, Dhaka

Garoukhali Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Garoukhali, Dhaka

GED (2010) Poverty, Environment and Climate Mainstreaming (PECM) Project. General Economics Division (GED), Planning Commission, Government of Bangladesh. http://www.pecm.org.bd

GoB (2004) The Constitution of the Peoples’ Republic of Bangladesh. Government of Bangladesh (GoB), Dhaka. http://www.parliament.gov.bd/Constitution_English/index.htm

GoB (2008) Multi donor trust fund for climate change (MDTF): Draft Concept Note. Government of Bangladesh

Godagari Pourashava (2011) Annual budget report. Godagari, Dhaka

Gomez-Echeverri L (2010) National funding entities: their role in the transition to a new paradigm of global cooperation on climate change. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Stockholm

Halder PK (2009) Community based adaptation (CBA) facilitation in South-west Bangladesh. Satkhira Unnayan Sangstha (SUS), Satkhira, Bangladesh. URL:http://unfccc.int/files/adaptation/application/pdf/sus_ap_update_sep_09._cba_sp.pdf

Haque AK (2009) An assessment of climate change on the annual development plan (ADP) of Bangladesh. United International University, Dhaka

Hedger M (2011) Climate finance in Bangladesh: lessons for development cooperation and climate finance at national level. Institute for Development Studies, London

Huq S, Rabbani G (2011) Climate change and Bangladesh: policy and institutional development to reduce vulnerability. J Bangladesh Stud 13:1–10

IMF (2001) Government Finance Statistics Manual. United Nations Statistics Division, United Nations, New York. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/

IMF (2011) IMF Executive Board Concludes 2011 Article IV Consultation with Bangladesh. Public Information Notice (PIN) No. 11/132. International Monetary Fund (IMF), Washington

Islam MM (2011) The people problem. Forum: a monthly publication of the Daily Star 5(7). http://www.thedailystar.net/forum/2011/July/people.htm

Jajira Pourashava (2011) Annual budget report. Jajira, Dhaka

Kunder Char Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Kunder Char, Dhaka

Lata Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Lata, Dhaka

LGD (1998) Local Government (Upazila Parishad) Act. Local Government Division (LGD), Ministry of Local Government and Cooperatives, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

LGD (2009a) Upazila Parishad (Amendment) Act. Local Government Division (LGD), Ministry of Local Government and Cooperatives, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

LGD (2009b) Local Government (Union Parishad) Act. Local Government Division (LGD), Ministry of Local Government and Cooperatives, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

MoPEMR (2011) UNDP Global Project: Capacity Development for Policy Makers to Address Climate Change. Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resource (MoPEMR), Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Narain U, Margulis S, Essam T (2011) Estimating costs of adaptation to climate change. Clim Pol 11(3):1001–1019

NRP (2010) Country evaluation Bangladesh: evaluation of the implementation of the Paris Declaration Phase-II. Natural Resources Planners (NRP), Dhaka

OECD (2003) Development and climate change in Bangladesh: focus on coastal flooding and the Sundarbans. S. Agrawal, T. Ota, A.U Ahmend, J. Smith and Mvan Aalst. OECD Environment Directorate/Development Cooperation Directorate Working party on global and structural policies; Working party on development cooperation and environment

OECD (2011) Handbook on the OECD-DEC climate markers. Preliminary version. http://www.oecd.org/dac/aidstatistics/48785310.pdf

Padmapukur Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Padmapukur, Dhaka

Paler Char Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Paler Char, Dhaka

Polycarp C (2010) Governing climate change finance in Bangladesh. An assessment of the Governance of Climate Finance and the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. A report prepared for the capacity development for development effectiveness facility, October 2010

Rishikul Union Parishad (2011) Annual budget report. Rishikul, Dhaka

Satkhira Pourashava (2011). Annual budget report. Satkhira, Dhaka

Schelling TC (1992) Some economics of global warming. Am Econ Rev 82(1):1–14

Shariatpur Development Society (SDS) (2007) Annual Report 2007. Shariatpur Development Society (SDS), Shariatpur, Dhaka. http://www.sdsbd.org/document/report-2007.pdf

Shushilan (2011) Shushilan Project Data Base. Shushilan, Khulna, Dhaka. http://www.shushilan.org/images/total%20project%20list%20170411.pdf

Stadelmann M, Roberts JT, Amchaelowa A (2010) Keeping a big promise: options for baselines to assess “new and additional” climate finance. CIS Working Paper nr 66 2010 University of Zurich, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1711158, 18 Nov 2010

Tanner T, Mitchell T (2008) Entrenchment or enhancement: could climate change adaptation help reduce chronic poverty? CPRC Working Paper. Chronic Poverty Research Centre, University of Manchester, Manchester

The Daily Star (2010) Upazila chairman vis a vis UNO. http://www.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=153870. Dated 7 Sep 2010

The Daily Star (2011) Power sector tops priority. Dated May 30 2011. http://www.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=187821. Accessed 22 July 2011

The Daily Star (2011) Key ministries face performance audit. Http://Www.Thedailystar.Net/Newdesign/News-Details.Php?Nid=197953. Dated 10 Aug 2011

UNAGF (2010) Report of Secretary General’s High level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing, 5 Nov 2010

World Bank (2010a) Bangladesh and state of the economy and FY11 Outlook. World Bank, Washington

World Bank (2010b) Economics of adaptation to climate change: Bangladesh case study. World Bank, Washington

World Bank (2010c) Meeting of the PPCR sub-committee: strategic programme for Climate Resilience Bangladesh. CIF report PPCR/SC.7/5 October 25, 2010. World Bank, Washington

Zakir A (2011) Bangladesh: National Progress Report on the Implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action. Disaster Management Bureau (DMB), Disaster Management and Relief Division, Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, Government of Bangladesh, Dhaka

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Japan

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Donnell, M. et al. (2013). Bangladesh Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review. In: Shaw, R., Mallick, F., Islam, A. (eds) Climate Change Adaptation Actions in Bangladesh. Disaster Risk Reduction. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54249-0_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54249-0_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-54248-3

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-54249-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)