Abstract

Østergaard, Santos, and Costa argue that entrepreneurship is increasingly perceived as a lifestyle and underscore the importance of understanding how entrepreneurial activities influence and are influenced by the entrepreneurs’ well-being. Through the lenses of well-being theories, building on the eudaimonic and hedonic dimensions of well-being, Østergaard et al. put forward a general framework to inspire future research and practice in entrepreneurship grounded on the psychological theory of well-being. According to Østergaard et al., integrating theories of well-being from psychology into entrepreneurship research is necessary to understand the impact of entrepreneurship on individuals’ mental health, promote quality of life, understand the motivations underlying entrepreneurial behavior, and further understand how entrepreneurs change their environment, discover opportunities, and advance societies in innovative ways.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Psychology is a mature field that has informed and contributed to different domains of science, such as management, organizational behavior, marketing, and entrepreneurship. In this chapter, we review how the different perspectives of psychology have contributed to understanding and explaining the foundation of individual behavior and how this affects society. Individuals act within societies, which constitute the context where individuals demonstrate their motivations, attitudes, and behaviors. Oftentimes, contextual idiosyncrasies and unique individual characteristics, skills, motivations, and cognitions lead people to imagine, plan, and create solutions to solve problems and challenges in society. One of the ways individuals improve and advance progress in their societies is through entrepreneurship: discovering or creating opportunities to solve problems. Entrepreneurship is an intentional behavior, which highly depends on the abilities of individuals (Krueger 2007). Therefore, relying on psychological theory to explain entrepreneurial behavior is extremely important, as entrepreneurship is primarily dependent on human action.

Psychology has contributed to the explanation of entrepreneurial behavior. As entrepreneurship transitioned from a purely economic field to focus more and more on individuals’ behavior, psychology has contributed to the addressing of critical questions in the field (Fayolle et al. 2005). For example, trait theory has contributed to the answering of the question “who is an entrepreneur?” by describing the personality traits most often associated with entrepreneurial behavior. For a review of this perspective, see, for example, Rauch and Frese (2007). When trait theory received criticism due to the lack of conclusive results and the lack of variability in results, entrepreneurship scholars went on to ask “what does an entrepreneur do?” (Gartner 1988). This question opened an avenue of research in entrepreneurship rooted in the behavioral approach of psychology. At the same time, to explain entrepreneurial behavior, motivational theories were brought to the field as well (the work of McClelland (1961) is central for this topic).

As the field moved to focus on the context where entrepreneurs act, in new ventures, other questions came up to focus on “how does an entrepreneur think?”. The description of entrepreneurs’ cognitive frameworks is deeply based on cognitive psychology (Mitchell et al. 2004, 2007; Costa et al. 2016) and is grounded in the idea that entrepreneurship is a conscious act (Krueger 2007) that depends on individuals’ experiences and expertise, and can be mostly learned (Drucker 1985). Currently, cognitive perspectives on entrepreneurship research are still central, giving rise to the creation of the entrepreneurial cognition subfield (Mitchell et al. 2002).

As the entrepreneurial field moves forward, questions regarding the development of entrepreneurial thinking and mind -set gain importance, and these are also deeply rooted in psychological theories. Consequently, entrepreneurship has moved from being a purely economic field, mainly targeting the creation of new ventures, to focusing on individual behavior, entrepreneurial thinking, and methods entrepreneurs use to create value for themselves and their community. Accordingly, entrepreneurship research nowadays goes beyond the venture creation process and takes different shapes and forms. We suggest that a legitimate and imperative next step for the entrepreneurship research field is to focus on the quality of life of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship research has focused on entrepreneurs’ personality, behaviors, and cognition. These approaches focusing on the well -being of entrepreneurs are necessary to understand the impact of entrepreneurship on individuals’ mental health, to promote quality of life, to understand the motivations underlying entrepreneurial behavior, and, ultimately, to continue understanding how these individuals change their environment, discover opportunities, and advance societies in innovative ways.

In this chapter, we first present a general overview on how psychological theory and measurement evolved over time. Next, entrepreneurship is emphasized from a psychological perspective and then we focus on well -being theory and open a discussion on how it is relevant for entrepreneurship research. We conclude with a general model that can inspire future research paths.

Perspectives from the Science of Psychology

The core study object of psychology is human beings’ behavior and mental processes in a variety of situations (Fowler 1990). Psychology relates to the study of individuals or groups of individuals with the goal of enhancing the current common understanding of human-related subjects, such as, the process of learning and how the optimal well -being of people are defined in different cultures. Additionally, psychological practice differs according to its subfield. For example, a clinical psychologist focuses on remedying mental disorders, while an organizational psychologist focuses on subjects related to the workplace, team dynamics, and career planning. Nevertheless, the common goal of practitioners is to assure individuals’ well -being in the different contexts of their lives and the optimal foundation for further personal development. Accordingly, in this chapter, we address well-being as a complementary field of psychology that has not yet been fully integrated into entrepreneurship, as a relevant opportunity for research. In our view, studying entrepreneurs’ quality of life, how entrepreneurs perceive their subjective well -being and happiness, is relevant to promote better practices and policies in entrepreneurship practice. Before delving into the details of well -being theories and entrepreneurship, we first focus on the key concepts of psychology and the various schools of thought that directly and indirectly have influenced entrepreneurship.

Psychology as a Scientific Field

Psychology is one of the oldest disciplines with recognized scientific value in the history of humanity, spanning different regions of the globe. Psychological knowledge had been preserved since ancient times and substantially increased in the Western world in the sixteenth century. For example, the four temperament types observed, described, and used by Hippocrates (460 BC–370 BC) for human diseases, and their later developments proposed by Galen, are still currently being used by psychology scholars (Jouanna 2010). In general, the science of psychology has had a great impact on contemporary scientists, and vice versa, such as the general theoretical enhancement by Francis Bacon (Serjeantson 2014) and, more specifically, the subject of anxiety as explored philosophically by Kierkegaard.

The first steps on how to measure psychological constructs started with Galton, who created statistical concepts and methods to study intelligence and human differences. Specifically, Galton was the pioneer of the phrase “nature versus nurture” (Galton 1869; Zaccaro 2007) which called attention, at that time, to the innate characteristics of individuals when compared to individual’s experiences. The development of psychological measurement methods was also developed in accordance with the contemporary influences of momentous scholars. For example, Galton was followed by Cronbach, who is well known for his measure of reliability in statistics and currently affecting most of the scholarly work by using Cronbach’s alpha. Related to this, Thorndike’s highly cited paper on halo error in ratings of cognitive ability testing and in the measuring of exceptional individuals affected both the measurement and the testing literature in psychology (Cortina et al. 2017).

In the stream of measuring the individual, Cattell developed psychometric-based personality traits (16 Personality Factors); Binet worked with intelligence tests; Wechsler developed an Intelligence Scale; and, the most used intelligence tests of today: the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) (Wechsler 1975). Other scholars proposed also means for the measurement of personality, as Eysenck who contributed knowledge from psychotherapy, and Luria who launched neuropsychology and the neuropsychological functioning based on soldiers with brain damage, which is still influencing our understanding of neuroscience.

The theoretical foundations of psychology took shape in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries based on the pioneering work of distinctive scholars. Well known are the psychological experiments by Skinner (the founder of behaviorism theory) and the stimulus-response experiments with dogs conducted by Pavlov. In opposition, Dewey (1896) postulated the unitary nature of the sensory motor circuit, and influenced many other experimental models and methods such as problem-based learning (PBL)—an educational method whereby the student mainly works with real problems in group-projects instead of having lectures, which is widely used in education today (Savery 2006), for instance, at most Danish Universities. Dewey’s argument was that every occasion is influenced by prior experiences and thus influences subsequent experiences as links in a chain.

A cornerstone in psychology is the psychoanalytic conception of personality as represented by Freud’s conceptions of the ego, superego, and id, standing in contrast to the archetypes of Jung. Freud and Jung inspired other scholars, such as Klein with his psychoanalytical therapy for children, and Erikson, who developed the theory of stages in psychosocial development, following in the footsteps of Freud.

Developmental psychology, the specific subfield of psychology that focuses on how and why individuals change over the span of their life, has several contributors starting with Piaget’s observations on the cognitive development of his own children, Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development, and the client-centered therapy of Rogers (1961). This latter theory argues that the optimal development, described as “the good life”, requires that individuals’ continually aim to fulfill their full potential. Accordingly, Rogers (1961) listed seven characteristics of a fully functioning person having an optimal development: (1) open to experience; (2) present in the moment and in the present process; (3) trusting one’s own judgment, having a sense of right and wrong, and able to choose appropriate behavior for each moment; (4) able to make a wide range of choices, fluently and concurrent with the necessary responsibility; (5) creative—as related to the feeling of freedom, for instance, shaping one’s own circumstances; (6) reliable and constructive in any action, while maintaining a balance between all of one’s needs; and (7) experiences joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage intensely, while having a rich, full, and exciting life. We come back to Rogers’ interpretation of the good life and the characteristics of a fully functional individual when discussing the well -being of an entrepreneur.

Educational and developmental psychology cover many of the same themes following Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (Wertsch 1984), personality (Mussen et al. 1963), role models (Van Auken et al. 2006), entrepreneurial potential (Santos et al. 2013; Jayawarna et al. 2014), and overcoming odds (Werner and Smith 1992).

Another psychological theory that concurrently is widely cited in different research fields is the theory of needs that often alternates with the theory of motives; the two significant scholars in this field are Maslow (1943) and McClelland (1985). Likewise, the group dynamics framework by Lewin (1947) and locus of control (Rotter 1990) have influenced other disciplines, such as leadership and coping theories, respectively. Other scholars have had prominent roles in the theoretical and empirical development of psychology, such as Ajzen with the Theory of Planned Behavior (1991) and Bandura on behavioral patterns, the Social Learning Theory (1971), and self-efficacy theory (Bandura and Adams 1977).

Psychological theories and psychology as a discipline are characterized by an eclectic approach. Accordingly, Robert S. Woodworth was awarded with a Gold Medal by the American Psychological Foundation in 1956 for his “unequaled contributions to shaping the destiny of scientific psychology” (Shaffer 1956, 587); through his creation of a general framework for psychological inquiry, his nurturing of students who later became influential psychologists, and for his textbooks that were thorough in scope, depth, and clarity. “Through these texts, Woodworth articulated an inclusive, eclectic vision for 20th-century psychology: diverse in its problems, but unified by the faith that careful empirical work would produce steady scientific progress” (Winston 2012, 51).

The eclectic approach has affected the existing schools of thought with combinations, overlaps, and the specified evolutions of concepts and content in many new directions. However, the present issues of the reliability and validity of properties, classifications, and test equivalence that scholars are struggling with are similar to the measurement issues that were relevant a hundred years ago (Cortina et al. 2017).

The Psychology of Entrepreneurship

The main traditional schools and disciplines within psychology are clinical, social, industrial and organizational (I/O), developmental, and educational psychology, all of which having played an important role in explaining entrepreneurial behavior and thinking. Recently, applied psychology and positive psychology have also contributed to explaining entrepreneurship (Gorgievski and Stephan 2016) and the subfield of psychology of entrepreneurship has gained importance (e.g., Baum et al. 2007).

Social psychology focuses on the activities, patterns, and characteristics of groups, clusters of entrepreneurial ventures, local environment, family context, and teams. For example, social psychology is relevant when we want to explain how an entrepreneur moves him or herself in this working environment, how he or she deals with the in and out group, and how becoming an entrepreneur can be a conscientious choice (Krueger 2007). I/O psychology and business psychology come also into play with topics such as work-life balance (e.g., Parasuraman et al. 1996), stress (Lazarus and Folkman 1984), hardiness (Maddi and Kobasa 1991), and leadership (Renko et al. 2015; Cogliser and Brigham 2004) that are particularly important for entrepreneurs. Cognitive psychology focuses on the intelligence, logical reasoning, problem-solving, coping strategies (e.g., Politis 2005), decision-making, and categorization processes which have been largely integrated in entrepreneurship (Baron 2004; Dimov 2011). Cognitive science has been a lens through which to understand various aspects of entrepreneurship, leading to the emergence of entrepreneurial cognition that aims to understand how entrepreneurs think and act. Entrepreneurial cognition refers to “the knowledge structures that people use to make assessments, judgments or decisions involving opportunity evaluation and venture creation and growth” (Mitchell et al. 2002, 97) and borrows theories, empirical evidence, and concepts from cognitive psychology and social cognition literature that have been useful to explain the development of entrepreneurs’ mental mechanisms and structures responsible for entrepreneurial behavior and thinking (Santos et al. 2016). During the last decade, entrepreneurial cognition research achieved significant findings about how entrepreneurs think and make decisions. The main findings fall into four main categories: (1) heuristic-based logic, (2) perceptual processes, (3) entrepreneurial expertise, and (4) effectuation (Mitchell et al. 2007).

New subfields emerge continually in accordance with the eclectic approach. Another recent perspective is positive psychology, which is also relevant in entrepreneurship (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Positive psychology focuses on the personal development toward becoming fully functioning in life and in terms of contextual well -being, for instance, regarding entrepreneurs, the subjective well -being in relation to money (Srivastava et al. 2001), growth willingness (Davidsson 1989), and early determinations of well -being (Caprara et al. 2006). Other previous studies focused on the up and down sides of being an entrepreneur (Baron et al. 2011), resilience and emotions (Welpe et al. 2012; Zampetakis et al. 2009), and in relation to organizational behavior (Luthans 2002).

The Psychology of Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs are individuals working in a very specific context, with demanding working characteristics, and performing unique tasks. Thus, psychology is a relevant theoretical lens to study entrepreneurs that seem to be committed to becoming fully functioning (Rogers 1961). In line with Rogers’ characteristics of optimal development, an entrepreneur is open to experience and present in the moment and the current process (Morris et al. 2012). An entrepreneur trusts in his or her own judgment of right and wrong (Casson 2003; Bottom 2004), and the best of entrepreneurs choose appropriate behavior, along with a wide range of other choices, with responsibility (Chakravarthy and Lorange 2008). An entrepreneur is also creative (Ward 2004) and shapes his or her own circumstances in relation to the feeling of freedom (McMullen et al. 2008). The best-functioning entrepreneurs are reliable and constructive in any action, while maintaining a balance between, for instance, control and trust (Shepherd and Zacharakis 2001). Often an aggressive need such as competition is changed into endurance and efficient problem-solving (Hsieh et al. 2007). An entrepreneur experiences joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage intensely, while having a rich, full, and exciting life (Sexton and Bowman 1985). According to effectuation theory, entrepreneurs are not able to decide the best course of action, but they have to deal with contingencies, to be flexible, and to use experimentation. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) further suggests that entrepreneurs engaged in the effectuation approach use the results of their decisions as a new information source to change the action, work with resources at their control, and to develop necessary adjustments.

Surprisingly, the well -being of the entrepreneur is underrepresented in entrepreneurship. Understanding entrepreneurship requires the analysis of the entrepreneur’s well -being, which, according to Dewey (2007), must be a circular chain in which his/her well-being determines entrepreneurial behavior, which in turn reciprocally benefits well-being perceptions. “Since the mental health of those who aspire to establish their ventures is a critical element of their capacity to perform well, an understanding of the role of individual choices of life goals and motives in promoting wellbeing not only sheds light on who benefits the most from entrepreneurship in terms of well -being, and why, but also helps entrepreneurs and those who support them in their pursuit of their entrepreneurial goals, which is equally valuable” (Shir 2015, 308–9). Hence, we expect that a psychological perspective with a focus on well -being shapes the study and practice of entrepreneurship toward the individual level and in a cross -disciplinary direction that enhances the quality of research, support, and development of entrepreneurship.

Psychological Well-Being Theory

Psychological well -being, happiness, and quality-of-life theories (Diener 1984) have not been very widely integrated in the entrepreneurship field, as opposed to in other domains of psychology, as discussed previously. Several recent exceptions (Shir 2015; Uy et al. 2017) are discussed later in this chapter. First, it is relevant to examine what psychological theory tells us about well-being.

The study of well-being was a reaction to previously mainstream research focusing on psychological disorders and sources of suffering. Since the 1950s, it was enhanced by “notable psychologists within positive (Csikszentmihalyi, Frederickson, Lyubomirsky, Seligman), cognitive (Forgas, Isen), social and humanistic (Deci, Elliot, Higgins, Keyes, Maslow, Rogers, Ryan, Ryff, Sheldon), personality (Tellegen), and clinical (Jahoda, Jung, Keyes) psychology, as well as more direct efforts by well-being researchers, mainly within the psychological sub-field of subjective well-being (Diener, Lucas)” (Shir 2015, 53).

Psychological well-being is an individual’s general psychological condition or the overall state needed for effective human functioning (Costa and McCrae 1980; Ryan and Deci 2001) and a phenomenon with distinctive cognitive, affective, and conative elements (Shir 2015). Literature on well-being entails two major approaches: eudaimonic and hedonic theories. Eudaimonic theories are grounded in humanistic psychology and relate to the ultimate desire of all humans to achieve psychological well-being or human happiness and meaning in life (Ryan and Deci 2001), and “the striving for perfection that represents the realization of one’s true potential” (Ryff 1995, 100). In this eudaimonic approach, well-being is a derivative of personal fulfillment and expressiveness (Waterman 1993), personal development (Erikson 1968), self-actualization (Maslow 1943), individuation (Jung 1933), and self-determination (Ryan and Deci 2001), or results more generally from being fully functional (Rogers 1961; Ryff 1989). Psychological well-being entails six main characteristics of the human actualization: autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery, and positive relatedness (Ryff and Singer 1998).

The hedonic approach is related to subjective happiness, the experience of pleasure as opposed to pain, the balance between positive and negative affect, and refers to satisfaction with different elements of human life (Ryan and Deci 2001). This approach is based on hedonic psychology and targets the maximization of human happiness (Ryan and Deci 2001). Within the hedonic approach, subjective well-being is very relevant, as it refers to the level of well-being that individuals experience according to their subjective evaluations of their life in any relevant domain, such as work, family, relationships, and health. Subjective well-being is conceptualized as a threefold construct including life satisfaction, presence of positive affect, and absence of negative affect (Diener and Lucas 1999).

These two well-being approaches include specific measures and operationalizations; for example, the eudaimonic approach is measured by Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being (Ryff and Keyes 1995), the Basic Need Satisfaction Scale (Ryan and Deci 2001), the Flourishing Scale (Diener et al. 2010), whereas the hedonic approach is measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 2010), Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper 1999), Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al. 1988), and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experiences (Diener et al. 2010). These two approaches have been driving theory developments in psychology and other related fields, such as organizational behavior and management, leading to the emergence of different theories on happiness and well-being, but, remarkably, not yet on entrepreneurship, to any great degree.

Nevertheless, Shir’s (2015) work is pioneering in studying well-being in the entrepreneurship context, and in uncovering the impact of well-being in entrepreneurship along with the impact of well-being from entrepreneurship. Shir defines entrepreneurial well-being in the following manner: “subjective well-being from entrepreneurship—is a distinctive and important cognitive-affective entrepreneurial outcome; a state of positive mental wellness with potentially far-reaching effects on entrepreneurs’ psychology, behavior, and performance” (2015, 22). His work integrates the development of a theoretical, context-specific theory of well-being in entrepreneurship and its payoff structure (Shir 2015). Yet this is, to the best of our knowledge, a solo effort to define and explore well-being in the entrepreneurship domain (Journal of Business Venturing is preparing a special issue on entrepreneurship and well-being that will certainly contribute to narrow this gap). Other main efforts were primarily developed by economists who focused on labor and happiness, studying the relationship between self-employment and work and life satisfaction (e.g., Blanchflower 2000; Andersson 2008). For example, Blanchflower and Oswald (1998) found that the self-employed were more satisfied with their jobs. Similarly, self-employed individuals from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries reported higher levels of job and life satisfaction than employees (Blanchflower 2000), but this positive effect was found to be limited to the rich (Alesina et al. 2004) or due to the specific psychological characteristics of the owners (Bradley and Roberts 2004). In the same line of results, Andersson (2008) showed that self-employment is related to an increase in job satisfaction, and that there is a positive correlation between self-employment and life satisfaction.

Engagement in entrepreneurial activities can favorably influence individuals’ well-being, as the entrepreneur is benefiting from a greater autonomy while developing his or her own meaningful job, pursuing a dream, generating value for the community, opening placement opportunities, and creating value. However, engagement in entrepreneurial activities can also be detrimental to an individual’s well-being, as the entrepreneur is operating in a highly uncertain environment, with constrained resources, increasing competition pressure, heavy economic and financial responsibility, and social pressure. Thus, it seems that the nexus between entrepreneurship and well-being is very complex, paradoxical, and under-researched. Scholars have not yet explored the mechanisms that explain the impact of entrepreneurship on well-being, nor the mechanisms that explain the impact of well-being on entrepreneurship, nor the predictors that are associated with these two relationships, nor how well-being levels fluctuate across the different stages of the entrepreneurship process, nor the well-being outcomes for the individual and for the venture. Understanding well-being in entrepreneurship is important to shield entrepreneurs’ mental health and to uncover the encouragement and motivations underlying the decision to engage in entrepreneurship.

Psychological Well-Being Theory Is Fundamental for Understanding the Individual Entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship is primarily an individual effort (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Shane 2003), as recognizing opportunities is fundamentally a mental process engaged in on an individual basis (Baron 2006). Entrepreneurial activity unfolds by virtue of the entrepreneur leading the decision-making processes (Sarasvathy 2001; McMullen and Shepherd 2006), leveraging resources (Alvarez and Busenitz 2001), founding the business (Hoang and Gimeno 2010), and maintaining motivation even during the most difficult times (DeTienne et al. 2008). Thus, studying the person as an entrepreneur is very important in order to understand and enhance performance across the diverse scope of entrepreneurial activities. Consequently, diverse scientific fields focusing on the individual appeared as relevant and adequate to converge on the entrepreneurship domain. This is why psychology comes into play and has been such a relevant framework to explore the unique characteristics of entrepreneurs (Hisrich et al. 2007; Baum et al. 2007; Frese and Gielnik 2014).

Entrepreneurship has been mainly drawing from specific domains within psychological theory, such as cognitive psychology (Mitchell et al. 2002), to explain opportunity recognition processes (Grégoire et al. 2010; Santos et al. 2015; Costa et al. 2018), to define entrepreneurial alertness (Gaglio and Katz 2001), and to understand heuristics in decision-making processes (Busenitz and Barney 1997), risk-taking (Palich and Bagby 1995), and creativity (Ward 2004). Affective theories (Forgas 2008) have also been very relevant to entrepreneurship research (Baron 2015) with a focus on the basis of entrepreneurial passion (Cardon et al. 2012; Cardon et al. 2009), studying emotions in entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation and venture efforts (Foo et al. 2009; Foo 2011), creative processes (Hayton and Cholakova 2012), and business failure (Shepherd et al. 2009), to name a few. Another domain of psychology that has been widely integrated in entrepreneurship research is personality (Rauch and Frese 2007; Østergaard 2017), specifically patterns of entrepreneurial personality (e.g., Brandstätter 2011), and its impact on different outcomes, such as venture growth (Lee and Tsang 2001).

Well-Being as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Activity

One of the seminal definitions of entrepreneurship describes it as a process through which individuals identify, evaluate, and exploit opportunities (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). Both individuals and opportunities are thus central for the entrepreneurial process to unfold and this relationship is typically referred to as the individual-opportunity nexus (Shane 2003). The literature is rich in attempts to explain and predict how this process unfolds. Several authors have focused on explaining which individual factors determine the ability to identify opportunities (Baron 2004, 2006), while others have focused on how opportunities come into existence (e.g., Alvarez and Barney 2007). Cognitive theory has offered important insights in describing the mental mechanisms that entrepreneurs engage in when identifying, evaluating, and exploiting opportunities.

As far as opportunities are concerned, a debate on whether opportunities are discovered or created has motivated several studies in the field, even though recent perspectives stress a realistic approach on how opportunities come into existence, emphasizing individual desire and agency efforts as key elements of opportunity identification (Ramoglou and Tsang 2016). We suggest that the entrepreneurial process, rooted in opportunity identification, evaluation, and exploitation, is highly dependent on the individual well-being of the entrepreneur as demonstrated in the entrepreneurial behavior. Interestingly, this association has never been explored.

However, since entrepreneurship and the identification of opportunities depends deeply on the individual effort of entrepreneurs, it seems that understanding entrepreneurship requires a deep insight into the fundamental relationship between entrepreneurial activity and the well-being of the individuals involved. In this sense, the six characteristics of human actualization (Ryff and Singer 1998) and the seven characteristics of optimal development, described as the good life, in which individuals fulfill their full potential (Rogers 1961), tend to provide insight into the well-being of entrepreneurs.

In fact, entrepreneurship has moved from being examined from a purely economic perspective, where organizations were the main level of analysis (e.g., Schumpeter 1934), to a perspective in which the individual is central to understand the entrepreneurial phenomena (Gartner et al. 1994). Concepts such as entrepreneurial mind -set, seen as the ability to master entrepreneurship through experience (Haynie et al. 2010), and entrepreneurial cognition, seen as the basis of entrepreneurial thinking and action (Mitchell et al. 2002), demonstrate that individual motivations, perceptions, and predispositions toward entrepreneurship are central to understanding entrepreneurial activity and success. Therefore, investigating the way individuals feel when engaging in entrepreneurship is of utmost importance to understanding entrepreneurial activity. Well-being, as an individual-level variable, can both determine the conditions in which to engage in entrepreneurship and be affected by the entrepreneurial activity outcome in return. While individual factors may determine entrepreneurship activity, this in turn may affect the subjective perception of well-being as well, consistent with the aforementioned circular chain (Dewey 2007).

First, we deal with the six main characteristics of human actualization: autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery, and positive relatedness (Ryff and Singer 1998) in relation to the seven characteristics of a fully functional person (Rogers 1961). We suggest that the characteristics of Rogers, as related to the experience of diverse feelings and a rich, full, and exciting life, align with the hedonic dimensions as the outcome of the entrepreneurial activity. Next, the crucial factors of individual entrepreneur’s well-being are integrated (Table 2.1).

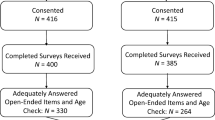

Finally, we propose a model according to which the entrepreneurial process depends on the eudaimonic characteristics of well-being as individual predictors of entrepreneurial behavior as reflected by opportunity identification, evaluation, and exploitation. The entrepreneurial activity, as the context in which entrepreneurs behave, think, and feel, influences the hedonic perceptions of well-being, this seen as the subjective well-being of the entrepreneur. See Fig. 2.1.

The model we propose is based on the assumption that well-being has a circular effect on the individual, which means that the eudaimonic aspects of well-being are predictors of entrepreneurial activity, while the subjective hedonic aspects result from engaging in entrepreneurial activity. In this sense, the eudaimonic dimensions of well-being refer to characteristics, which are endogenous to the individual. Autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery, and positive relatedness affect an individual and are likely to motivate entrepreneurial activity. Specifically, individuals with high autonomy are characterized as being self-determining and independent, capable of persisting with their thinking even under social pressure, being able to regulate their behavior internally, and guided by self-evaluation and by their personal standards (Ryff and Singer 1998). Individuals with high personal growth strive for continued self-personal development and growth, targeting constant improvement, engaging in new experiences and discoveries, and continuously evolving based on their self-knowledge and effectiveness (Ryff and Singer 1998). Regarding those individuals with high self-acceptance, they are characterized as having a positive attitude toward themselves, but, at the same time, they accept the positive and negative aspects of their self, and feel comfortable about their past life (Ryff and Singer 1998). Individuals with a high life purpose have established goals in life and a perception of directedness. They also perceive the present and past meaning of life, and have strong goals, vision, and objectives for living (Ryff and Singer 1998). Having a high mastery means that individuals feel competence in managing a particular task, controlling external activities, and using the opportunities in the environment effectively (Ryff and Singer 1998). Having positive relations with others, that is, positive relatedness, is typical of individuals with warm, fulfilling, and trusting relationships, being attentive to others’ general health, happiness, and fortunes, capable of developing strong ties with others that are based on empathy, affection, and intimacy, and exhibiting resilience in the give and take of any relationship (Ryff and Singer 1998). These eudaimonic dimensions of well-being are not stable but rather change over time, depending on the context and performance perceptions of the individual.

Thus, these six characteristics of eudaimonic well-being are in line with the general evidence on the main individual characteristics positively associated with identification, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities, such as those exhibited by entrepreneurs that are motivated by the execution of higher autonomy and personal realization and recognition (Carter et al. 2003), and by having a high internal locus of control (Brockhaus 1975) and, thereby, the experience of strong social networks and social capital (Greve and Salaff 2003).

In our model, we follow the conceptualization of entrepreneurial activity as grounded in the identification, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities. These actions cover the largest part of the entrepreneurial process. Entrepreneurial opportunities set up the preconditions from which the entrepreneur acts. Engaging in the different activities related to entrepreneurship is known to influence the feelings of the individuals involved, especially when these activities are central to the personality of entrepreneurs (Cardon et al. 2009). Therefore, entrepreneurial activity is likely to influence entrepreneurs’ subjective perception of well-being, namely their satisfaction with life and happiness in general, resulting in an optimal balance between positive and negative affect.

Our model stresses the importance of well-being in the entrepreneurial process by emphasizing that the individual characteristics determining involvement in entrepreneurial act, those of opportunity discovery, evaluation, and exploitation, which in turn affects the subjective perception of well-being. Moreover, we conceive this model as dynamic, and, as the eudaimonic dimensions of well-being are changeable, there is a potential feedback loop so that positive benefits of well-being for entrepreneurial activity increase the sense of well-being in a virtuous circle. In addition, this framework opens several new avenues of research, such as, for example, on the dimensions of well-being and how entrepreneurship shapes the various dimensions of entrepreneurial well-being, how well-being changes depending on situations, conditions, and entrepreneurial experiences, and what the predictors and outcomes of entrepreneurial well-being are.

Future research should also consider particular conditions that interfere with the model, for example, how different types of ventures influence the well-being of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs create different types of ventures—survival, lifestyle, managed growth, and aggressive growth ventures (Morris et al. 2018)—and these require different tangible and intangible resource configurations. These four types are defined based on a range of criteria including annual growth rate, time horizon, management focus, management style, entrepreneurial orientation, technology investment, liability of smallness, source of finance, exit approach, management skills, structure, reward emphasis, and founder motives (Morris et al. 2018). Building on this typology, if an individual aspires to have a work-family balance, to create value for a particular location while generating profit to provide a steady income and financial comfort, then he/she will launch a lifestyle venture and not an aggressive growth venture that, in essence, requires other individual choices and commitments. Thus, while positive well-being may be an important factor in enabling entrepreneurship at the start, the pursuit of well-being as an objective may undermine business optimization. And, as theory in entrepreneurial well-being advances, there is also a need to discuss how to measure the impact of well-being in entrepreneurship (and vice versa) and prepare studies with adequate research designs that allow the establishment of causal relationships, such as longitudinal designs.

Conclusion

Psychology focuses on the importance of the general well -being of individuals in different contexts. Despite the fact that psychology has already informed entrepreneurship in several relevant topics, we do not yet know much about the well -being of entrepreneurs. As entrepreneurship is progressively a more frequent choice for individuals, it is critical to understand how well -being influences the entrepreneurial process, and also, how well -being can motivate or trigger individuals to start their own venture. Indeed, individual decision-making (McMullen and Shepherd 2006), entrepreneurial motivation (Shane et al. 2003), entrepreneurial identity (Down and Reveley 2004), and founder identity (Powell and Baker 2014) are relevant constructs to explain the relation between well -being and entrepreneurship. Based on this conceptual foundation, empirical research is needed to further explore the relations set forth here, and specifically to further clarify other variables that might be interacting here, such as venture types (Morris et al. 2018), occupational experience, education, age, gender, personality, and social background, to state a few.

As an effort to understand the interplay between objective and subjective notions of well -being, in this chapter, we put forward a framework integrating the eudaimonic and hedonic perspectives of well -being. We hope that our model inspires future research, calls the attention of scholarly research on well -being and entrepreneurship, and sparks the curiosity of the readers toward these topics to continuously look for more theoretical and practical connections between psychology and entrepreneurship. By grounding research on well-informed theories, and using reliable methodologies and rigorous data analysis processes, psychology will continue to contribute to the development of entrepreneurship theory and practice.

References

Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211.

Alesina, Alberto, Rafael Di Tella, and Robert MacCulloch. 2004. Inequality and Happiness: Are Europeans and Americans Different? Journal of Public Economics 88: 2009–2042.

Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2007. Discovery and Creation: Alternative Theories of Entrepreneurial Action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1 (1–2): 11–26.

Alvarez, Sharon A., and Lowell W. Busenitz. 2001. The Entrepreneurship of Resource-Based Theory. Journal of Management 27 (6): 755–775.

Andersson, Pernilla. 2008. Happiness and Health: Well-Being Among the Self-Employed. Journal of Socio-Economics 37 (1): 213–236.

Bandura, Albert. 1971. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bandura, Albert, and Nancy E. Adams. 1977. Analysis of Self-Efficacy Theory of Behavioral Change. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1: 287–310.

Baron, Robert A. 2004. The Cognitive Perspective: A Valuable Tool for Answering Entrepreneurship’s Basic ‘Why’ Questions. Journal of Business Venturing 19 (2): 221–239.

———. 2006. Opportunity Recognition as Pattern Recognition: How Entrepreneurs “Connect the Dots” to Identify New Business Opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives 20 (1): 104–119.

———. 2015. Affect and Entrepreneurship. Vol. 3, in Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 1–3.

Baron, Robert A., Jintong Tang, and Keith M. Hmieleski. 2011. The Downside of Being ‘up’: Entrepreneurs’ Dispositional Positive Affect and Firm Performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 5 (2): 101–119.

Baum, Robert J., Michael Frese, and Robert A. Baron. 2007. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. London: Psychology Press.

Blanchflower, David G. 2000. Self-Employment in OECD Countries. Labour Economics 7: 471–505.

Blanchflower, David G., and Andrew J. Oswald. 1998. What Makes an Entrepreneur? Journal of Labour Economics 16 (1): 26–60.

Bottom, William P. 2004. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Academy of Management Review 29 (4): 695–698.

Bradley, Don E., and James A. Roberts. 2004. Self-Employment and Job Satisfaction: Investigating the Role of Self-Efficacy, Depression, and Seniority. Journal of Small Business Management 42: 37–58.

Brandstätter, Hermann. 2011. Personality Aspects of Entrepreneurship: A Look at Five Met-Analyses. Personality and Individual Differences 51 (3): 222–230.

Brockhaus, Robert H. 1975. I-E Locus of Control Scores Are Predictors of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Academy of Management Proceedings 1: 433–435.

Busenitz, Lowell W., and Jay B. Barney. 1997. Differences Between Entrepreneurs and Managers in Large Organizations: Biases and Heuristics in Strategic Decision-Making. Journal of Business Venturing 12 (1): 9–30.

Caprara, Gian Vittorio P., Steca M. Gerbino, M. Paciello, and G. Vecchio. 2006. Looking for Adolescent’s Well-Being: Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Determinants of Positive Thinking and Happiness. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 15 (1): 30–43.

Cardon, Melissa S., Johan Wincent, Jagdip Singh, and Mateja Drnovsek. 2009. The Nature and Experience of Entrepreneurial Passion. Academy of Management Review 34 (3): 511–532.

Cardon, Melissa S., Maw-Der Foo, Dead A. Shepherd, and Johan Wiklund. 2012. Exploring the Heart: Entrepreneurial Emotion Is a Hot Topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 1–10.

Carter, Nancy M., William B. Gartner, Kelly G. Shaver, and Elizabeth J. Gatewood. 2003. The Career Reasons of Nascent Entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing 18 (1): 13–39.

Casson, Mark. 2003. The Entrepreneur: An Economic Theory. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Chakravarthy, Bala, and Peter Lorange. 2008. Profit or Growth?: Why You Don’t Have to Choose. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing.

Cogliser, Claudia C., and Keith H. Brigham. 2004. The Intersection of Leadership and Entrepreneurship: Mutual Lessons to Be Learned. The Leadership Quarterly 15 (6): 771–799.

Cortina, Jose M., Herman Aguinis, and Richard P. DeShon. 2017. Twilight of Dawn or of Evening? A Century of Research Methods in the Journal of Applied Psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology 102 (3): 274.

Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1980. Influence of Extraversion and Neuroticism on Subjective Well-Being: Happy and Unhappy People. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38 (4): 668–678.

Costa, Sílvia F., Susana C. Santos, Dominika Wach, and António Caetano. 2018. Recognizing Opportunities Across Campus: The Effects of Cognitive Training and Entrepreneurial Passion on the Business Opportunity Prototype. Journal of Small Business Management 56 (1): 51–75.

Costa, Sílvia F., Michel L. Ehrenhard, António Caetano, and Susana C. Santos. 2016. The Role of DifferentOpportunities in the Activation and Use of the Business Opportunity Prototype. Creativity and InnovationManagement 25(1): 58–72.

Davidsson, Per. 1989. Entrepreneurship—and After? A Study of Growth Willingness in Small Firms. Journal of Business Venturing 4 (3): 211–226.

DeTienne, Dawn R., Dean A. Shepherd, and Julio O. De Castro. 2008. The Fallacy of “Only the Strong Survive”: The Effects of Extrinsic Motivation on the Persistence Decisions of Under-Performing Firms. Journal of Business Venturing 23 (5): 528–546.

Dewey, John. 1896. The Reflex arc Concept in Psychology. Psychological Review 3 (4): 357.

———. 2007. Experience and Education. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Diener, Ed. 1984. Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542–575.

Diener, Ed, and Richard E. Lucas. 1999. Personality and Subjective Well-Being. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, ed. Daniel Kahneman, Ed Diener, and Norbert Schwarz, 213–229. New York: Russell-Sage.

Diener, Ed, Derrick Wirtz, William Tov, Chu Kim-Prieto, Dong-won Choi, Shigehiro Oishi, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2010. New Well-Being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Social Indicators Research 97: 143–156.

Dimov, Dimo. 2011. Grappling with the Unbearable Elusiveness of Entrepreneurial Opportunities. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (1): 57–81.

Down, Simon, and James Reveley. 2004. Generational Encounters and the Social Formation of Entrepreneurial Identity: “Young Guns” and “Old Farts”. Organization 11 (2): 233–250.

Drucker, Peter F. 1985. Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Vol. 2. New York: Harper & Row.

Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Childhood and Society. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Fayolle, Alain, Jan Ulijn, and Paula Kyrö. 2005. The Entrepreneurship Debate in Europe: A Matter of History and Culture? The European Roots of Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurship Research. In Entrepreneurship Research in Europe: Perspectives and Outcomes, ed. Alain Fayolle, Jan Ulijn, and Paula Kyrö, 1–46. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Foo, Maw D. 2011. Emotions and Entrepreneurial Opportunity Evaluation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (2): 375–393.

Foo, Maw-Der, Robert A. Baron, and Marilyn A. Uy. 2009. How Do Feelings Influence Effort: An Empirical Study of Entrepreneurs’ Affect and Venture Effort. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 1086–1094.

Forgas, Joseph P. 2008. Affect and Cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science 3 (2): 94–101.

Fowler, Raymond D. 1990. Psychology: The Core Discipline. American Psychologist 45 (1): 1.

Frese, Michael, and Michael M. Gielnik. 2014. The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1: 413–438.

Gaglio, Connie M., and Jerome A. Katz. 2001. The Psychological Basis on Opportunity Identification: Entrepreneurial Alertness. Small Business Economics 16 (2): 95–111.

Galton, Francis. 1869. Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry into Its Laws and Consequences. London: Macmillan and Company.

Gartner, William B. 1988. Who Is an Entrepreneur? Is the Wrong Question. American Journal of Small Business 13 (1): 11–32.

Gartner, William B., Kelly G. Shaver, Elizabeth Gatewood, and Jerome A. Katz. 1994. Finding the Entrepreneur in Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 18 (3): 5–9.

Gorgievski, Marjan J., and Ute Stephan. 2016. Advancing the Psychology of Entrepreneurship: A Review of the Psychological Literature and an Introduction. Applied Psychology 65 (3): 437–468.

Grégoire, Denis A., Pamela S. Barr, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2010. Cognitive Processes of Opportunity Recognition. Organizational Science 21 (2): 413–431.

Greve, Arent, and Janet W. Salaff. 2003. Social Networks and Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28 (1): 1–22.

Haynie, Michael J., Dean Shepherd, Elaine Mosakowski, and P.C. Earley. 2010. A Situated Metacognitive Model of the Entrepreneurial Mindset. Journal of Business Venturing 25 (2): 217–229.

Hayton, James C., and Magdalena Cholakova. 2012. The Role of Affect in the Creation and Intentional Pursuit of Entrepreneurial Ideas. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 41–68.

Hisrich, Robert, Janice Langan-Fox, and Sharon Grant. 2007. Entrepreneurship Research and Practice: A Call to Action for Psychology. American Psychologist 62 (6): 575–589.

Hoang, Ha, and Javier Gimeno. 2010. Becoming a Founder: How Founder Role Identity Affects Entrepreneurial Transitions and Persistence in Founding. Journal of Business Venturing 25 (1): 41–53.

Hsieh, Chihmao, Jack A. Nickerson, and Todd R. Zenger. 2007. Opportunity Discovery, Problem Solving and a Theory of the Entrepreneurial Firm. Journal of Management Studies 44 (7): 1255–1277.

Jayawarna, Dilani, Oswald Jones, and Allan Macpherson. 2014. Entrepreneurial Potential: The Role of Human and Cultural Capitals. International Small Business Journal 32 (8): 918–943.

Jouanna, Jacques. 2010. Hippocrates as Galen’s Teacher. Studies in Ancient Medicine 35: 1–21.

Jung, Carl G. 1933. Modern Man in Search of a Soul. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Krueger, Norris F. 2007. What Lies Beneath? The Experiential Essence of Entrepreneurial Thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (1): 123–138.

Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Lee, Don Y., and Erik W.K. Tsang. 2001. The Effects of Entrepreneurial Personality, Background and Network Activities on Venture Growth. Journal of Management Studies 38 (4): 583–602.

Lewin, Kurt. 1947. Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change. Human Relations 1 (1): 5–41.

Luthans, Fred. 2002. Positive Organizational Behavior: Developing and Managing Psychological Strengths. Academy of Management Executive 16 (1): 57–72.

Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Heidi S. Lepper. 1999. A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation. Social Indicators Research 46: 137–155.

Maddi, Salvatore R., and Suzanne C. Kobasa. 1991. The Development of Hardiness. In Stress and Coping, ed. Alan Monat and Richard S. Lazarus. New York: Columbia University Press.

Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. Conflict, Frustration, and the Theory of Threat. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 38 (1): 81–86.

McClelland, David C. 1961. The Achieving Society. Princeton: Van Nostrand.

———. 1985. Human Motivation. Glenview: Scott Foresman.

McMullen, J.S., and D.A. Shepherd. 2006. Entrepreneurial Action and the Role of Uncertainty in the Theory of the Entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review 31 (1): 132–152.

McMullen, Jeffery S., D. Ray Bagby, and Leslie E. Palich. 2008. Economic Freedom and the Motivation to Engage in Entrepreneurial Action. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (5): 875–895.

Mitchell, Ronald K., Lowell W. Busenitz, Theresa Lant, McDougall P. Patricia, Eric A. Morse, and J. Brock Smith. 2002. Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Cognition: Rethinking the People Side of Entrepreneurship Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 93–104.

———. 2004. The Distinctive and Inclusive Domain of Entrepreneurial Cognition Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28 (6): 505–518.

Mitchell, Ronald K., Lowell W. Busenitz, Barbara Bird, Connie M. Gaglio, Jeffery S. McMullen, Eric A. Morse, and J. Brock Smith. 2007. The Central Question in Entrepreneurial Cognition Research 2007. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31: 1–27.

Morris, Michael H., Donald F. Kuratko, Minet Schindehutte, and April J. Spivack. 2012. Framing the Entrepreneurial Experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 11–40.

Morris, M.H., X. Neumeyer, Y. Jang, and D.F. Kuratko. 2018. Distinguishing Types of Entrepreneurial Ventures: An Identity-Based Perspective. Journal of Small Business Management 56 (3): 453–474.

Mussen, Paul H., John J. Conger, and Jerome Kagan. 1963. Child Development and Personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Østergaard, Annemarie. 2017. The Entrepreneurial Personalities: A Study of Personality Traits and Leadership Preferences of Entrepreneurs. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

Palich, Leslie L., and Ray D. Bagby. 1995. Using Cognitive Theory to Explain Entrepreneurial Risk-Taking: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing 10 (6): 425–438.

Parasuraman, Saroj, Yasmin S. Purohit, Veronica M. Godshalk, and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1996. Work and Family Variables, Entrepreneurial Career Success, and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 48 (3): 275–300.

Politis, Diamanto. 2005. The Process of Entrepreneurial Learning: A Conceptual Framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29 (4): 399–424.

Powell, Erin E., and Ted Baker. 2014. It’s What You Make of It: Founder Identity and Enacting Strategic Responses to Adversity. Academy of Management Journal 57 (5): 1406–1433.

Ramoglou, Stratos, and Eric W.K. Tsang. 2016. A Realist Perspective of Entrepreneurship: Opportunities as Propensities. Academy of Management Review 41 (3): 410–434.

Rauch, Andreas, and Michael Frese. 2007. Let’s Put the Person Back into Entrepreneurship Research: A Meta-Analysis on the Relationship Between Business Owners’ Personality Traits, Business Creation, and Success. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 16 (4): 353–385.

Renko, Maija, Ayman El Tarabishy, Alan L. Carsrud, and Malin Brännback. 2015. Understanding and Measuring Entrepreneurial Leadership Style. Journal of Small Business Management 53 (1): 54–74.

Rogers, Carl R. 1961. On Becoming a Person: A Psychotherapist’s View of Psychotherapy. London: Constable.

Rotter, Julian B. 1990. Internal Versus External Control of Reinforcement: A Case History of a Variable. The American Psychologist 45 (4): 489–493.

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2001. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1): 141–166.

Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness Is Everything, or Is It? Explorations on the Meaning of Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57 (6): 1069–1081.

———. 1995. Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life. Current Directions in Psychological Science 4 (4): 99–104.

Ryff, Carol D., and Corey L. M. Keyes. 1995. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 719 (727).

Ryff, C.D., and B. Singer. 1998. The Contours of Positive Human Health. Psychological Inquiry 9 (1): 1–28.

Sarasvathy, Saras D. 2001. Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. The Academy of Management Review 26 (2): 243.

———. 2008. Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Savery, John R. 2006. Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning 1 (1): 3.

Santos, Susana C., António Caetano, Robert Baron, and Luís Curral. 2015. Prototype Models of Opportunity Recognition and the Decision to Launch a New Venture Identifying the Basic Dimensions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 21 (4): 510–538.

Santos, Susana C., António Caetano, and Luís Curral. 2013. Psychosocial Aspects of Entrepreneurial Potential. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 26 (6): 661–685.

Santos, Susana C., Sílvia F. Costa, Xaver Neumeyer, and António Caetano. 2016. Bridging Entrepreneurial Cognition Research and Entrepreneurship Education: What and How. In Annals of Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy – 2016, ed. Michael H. Morris and Eric Liguori, 83–108. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Seligman, Martin E.P., and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. Positive Psychology. American Psychologist 55 (1): 5–14.

Serjeantson, R. 2014. Francis Bacon and the “Interpretation of Nature” in the Late Renaissance. Isis 105 (4): 681–705.

Sexton, Donald L., and Nancy Bowman. 1985. The Entrepreneur: A Capable Executive and More. Journal of Business Venturing 1: 129–140.

Shaffer, Laurance F. 1956. Presentation of the First Gold Medal Award. American Psychologist 11: 587–588.

Shane, Scott A. 2003. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Shane, Scott A., and Sankaran Venkataraman. 2000. The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research. Academy of Management Review 25 (1): 217–226.

Shane, Scott A., Edwin A. Locke, and Christopher J. Collins. 2003. Entrepreneurial Motivation. Human Resource Management Review 13 (2): 257–279.

Shepherd, Dean A., and Andrew Zacharakis. 2001. The Venture Capitalist-Entrepreneur Relationship: Control, Trust and Confidence in Co-operative Behaviour. Venture Capital 3 (2): 129–149.

Shepherd, Dean A., Johan Wiklund, and Michael J. Haynie. 2009. Moving Forward: Balancing the Financial and Emotional Costs of Business Failure. Journal of Business Venturing 24 (2): 134–148.

Shir, Nadav. 2015. Entrepreneurial Well-Being: The Payoff Structure of Business Creation. PhD Dissertation, Stockholm School of Economics.

Srivastava, Abhishek, Edwin A. Locke, and Kathryn M. Bartol. 2001. Money and Subjective Well-Being: It’s Not the Money, It’s the Motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 80 (6): 959–971.

Uy, Marilyn A., Shuhua Sun, and Maw-Der Foo. 2017. Affect Spin, Entrepreneurs’ Well-Being, and Venture Goal Progress: The Moderating Role of Goal Orientation. Journal of Business Venturing 32 (4): 443–460.

Van Auken, Howard, Fred L. Fry, and Paul Stephens. 2006. The Influence of Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 11 (2): 157–167.

Ward, Thomas B. 2004. Cognition, Creativity, and Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 19 (2): 173–188.

Waterman, Alan S. 1993. Two Conceptions of Happiness: Contrasts of Personal Expressiveness (Eudaimonia) and Hedonic Enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64 (4): 678–691.

Watson, D., L.A. Clark, and A. Tellegen. 1988. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 1063–1070.

Wechsler, David. 1975. Intelligence Defined and Undefined: A Relativistic Appraisal. American Psychologist 30 (2): 135–139.

Welpe, Isabell M., Matthias Spörrle, Dietmar Grichnik, Theresa Michl, and David B. Audretsch. 2012. Emotions and Opportunities: The Interplay of Opportunity Evaluation, Fear, Joy, and Anger as Antecedent of Entrepreneurial Exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 69–96.

Werner, Emmy E., and Ruth S. Smith. 1992. Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children from Birth to Adulthood. Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press.

Wertsch, James V. 1984. The Zone of Proximal Development: Some Conceptual Issues. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 1984 23: 7–18.

Winston, Andrew S. 2012. Robert S. Woodworth and the Creation of an Eclectic Psychology. In Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology, ed. Wade E. Pickren, Donald A. Dewsbury, and Michael Wertheimer, vol. Vol. 6, 51–66. New York: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

Zaccaro, Stephen J. 2007. Trait-Based Perspectives of Leadership. American Psychologist 62 (1): 6–16.

Zampetakis, Leonidas A., Konstantinos Kafetsios, Nancy Bouranta, Tod Dewett, and Vassilis S. Moustakis. 2009. On the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 15 (6): 595–618.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Østergaard, A., Santos, S.C., Costa, S.F. (2018). Psychological Perspective on Entrepreneurship. In: Turcan, R., Fraser, N. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91611-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91611-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-91610-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-91611-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)