Abstract

Motivated by the poorly understood nature of the term “mindsets” in the domain of entrepreneurship, we embarked on an exploration encompassing three research goals: a) defining and assessing growth mindsets in entrepreneurship, b) investigating how growth mindsets in entrepreneurship correlate with personality constructs, and c) exploring how growth mindsets predict motivation related to being an entrepreneur. Overall, findings from a sample of entrepreneurs (n = 264) and non-entrepreneurs (n = 330) reveal evidence consistent with the inference that a unidimensional, ‘growth mindset in entrepreneurship’ (GME) construct underlies five distinct mindset measures closely related to entrepreneurship: mindsets of leadership, mindsets of creativity, person mindsets, mindsets of intelligence, and mindsets of entrepreneurial ability. This GME construct correlated positively with conscientiousness and openness (albeit with small effects), but did not consistently correlate with extraversion, agreeableness, or neuroticism. We also found significant and positive relations for the GME with resilience and need for achievement, but a significant (and unexpected) negative correlation with risk-taking. With respect to motivation (operationalized via expectancy-value theory), GME predicted self-efficacy, but only for individuals who did not identify as entrepreneurs. GME exhibited limited utility in predicting enjoyment, utility, or identity evaluations related to value, but was robustly linked to cost evaluations. We discuss the implications of these findings and suggest directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

What does it take to be an entrepreneur? Academic literature highlights the notion of a distinctive “entrepreneurial mindset” that sets entrepreneurs apart. Although there is considerable heterogeneity among definitions, the term “entrepreneurial mindset” is typically understood to be more than just a belief or attitude—it is a way of thinking, acting, and being, an aligned set of traits, skills, motivations, and abilities that makes someone an entrepreneur (e.g., Haynie et al., 2010; Kuratko et al., 2020; Shaver et al., 2019). For example, ‘entrepreneurial mindset’ can be defined as a “constellation of motives, skills, and thought processes that distinguish entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurs and that contribute to entrepreneurial success” (Davis et al., 2016, p. 2).

Overall, the preponderance of research related to the ‘entrepreneurial mindset’ focuses on the traits and abilities that make someone an entrepreneur. Unfortunately, scholars pay far less attention to the related, yet important, question of whether people perceive that the constellation of these attributes can be actively cultivated and developed, or is instead innate—a talent with which people are blessed from birth. In the current paper, we highlight this latter question. Our approach is built on the longstanding literature illustrating the importance of beliefs about whether human attributes are innate or can be developed—what psychologists originally referred to as implicit theories (Dweck, 2000; Dweck & Leggett, 2000). The beliefs are ‘implicit’ because they can guide behavior and create meaning systems without being stated explicitly, and are ‘theories’ because they include generalities about the types of qualities that characterize most people. This framework distinguishes between two main types of implicit theories—or “mindsets” as they are now called. Individuals can vary in their mindsets from believing attributes are relatively static entities (fixed mindset) to believing attributes can be developed (growth mindset). Overall, drawing on this framework, the present research examines to what extent people believe that the traits and abilities essential for entrepreneurship are malleable versus fixed, and we explore possible consequences of these differential beliefs. Our study emerges from a research context characterized by expanding interest and application of mindset theory, which has thus far been directed primarily toward academic achievement, health, and social functioning (Sisk et al., 2018). We apply this expanding body of research to the domain of entrepreneurship. We pursue three specific research goals, outlined below.

Goal 1: Assessment of Mindsets

To operationally define and assess mindsets of entrepreneurial attributes, we first answer a fundamental psychometric question—namely, there is a gap in the literature in that researchers have yet to formally ascertain whether the underlying latent structure of key mindsets is continuous or categorical in nature. Despite multiple recent contributions in the literature, this has not yet been done formally (e.g., Chen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Furthermore, scholars have not yet examined the possibility that the multiple mindsets relevant to a specific domain, such as entrepreneurship, might reduce to a single, underlying, “core” growth mindset. So, we examine five growth mindsets that are most closely linked to entrepreneurship: mindset of entrepreneurial ability, mindset of intelligence, mindset of leadership, mindset of creativity, and mindset of people (e.g., Burnette et al., 2020b). For our first research goal, we seek to answer the following two questions:

Research Question 1: Is the underlying structure of growth mindsets that are relevant to entrepreneurship categorical or continuous?

Research Question 2: Does a single construct underlie the mindsets most relevant to entrepreneurship, suggesting a core “growth mindset in entrepreneurship (GME),” or are there multiple mindset constructs? If so, what are they?

Goal 2: Correlates of Mindsets

The second research goal is to explore how mindsets of entrepreneurial attributes relate to personality traits. A venerable body of research has examined the personality traits that are germane to entrepreneurs (and non-entrepreneurs), yet no extant work has looked comprehensively at the links between personality and the mindsets most relevant to entrepreneurship (e.g., Carland III et al., 1995; McGrath et al., 1992; Stewart Jr & Roth, 2001). Addressing this lacuna in the literature, we first show how mindsets of entrepreneurship attributes are related to The Big Five dimensions: openness, extroversion, agreeableness, neuroticism and conscientious. We also examine correlations with three additional personality constructs that are relevant to entrepreneurship—risk-taking, resilience, and need for achievement. The goal of the current work is to show how growth mindsets relate to, yet are distinct from, these important entrepreneurial-minded attributes.

With regard to prior mindset research, theory and findings suggest that growth mindsets foster greater willingness to take on challenges to pursue achievements even in the face of obstacles, and to persist in pursuit of one’s goals (Burnette et al., 2013; Rege et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2015; Yeager & Dweck, 2012). We are cognizant of these findings in applying them to the domain of entrepreneurship and we suggest that growth mindsets of entrepreneurship should correlate positively with three attributes closely related to entrepreneurship: risk-taking, resilience, and need for achievement. Accordingly, we ask the following two questions:

Research Question 3: Are growth mindsets of entrepreneurial attributes related to the Big Five traits?

Research Question 4: Are growth mindsets of entrepreneurial attributes correlated positively with risk-taking, resilience, and need for achievement?

Goal 3: Mindsets and Motivation

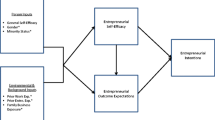

The third goal of this research is to determine whether the previously identified dimension(s) or class(es) of entrepreneurial mindsets relate to entrepreneurial motivation, which has never been done. We draw on expectancy-value theory (Eccles et al., 1983), which outlines how the evaluations regarding one’s capacity to do well (efficacy) and the enjoyment and utility of attaining the goal (value) predict motivation to engage, persist, and succeed in particular tasks.

Mindsets and Efficacy

In general, self-efficacy can be defined as people’s confidence in their abilities, or the belief that actions will lead to desired end states (Bandura, 1977). Growth mindsets indicate a belief that people have the ability to change, grow, and succeed, even in the face of obstacles. Prior research, both correlational and experimental, across several mindset domains demonstrates that growth mindsets tend to predict greater expectations for success and greater levels of self-efficacy (Donohoe et al., 2012; Dweck & Leggett, 2000; Orvidas et al., 2018; Sriram, 2014; Thomas et al., 2019).

Mindsets and Value

According to expectancy-value theory, value can be described as self-relevance and importance (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Renko et al., 2012). Intuitively, the more one believes that their traits and abilities are malleable and that they can improve, the more one can see the value in growing or developing skills and abilities. Indeed, research demonstrates a link between growth mindsets and value in several domains (Dweck, 2000; Orvidas et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2019). Here, growth mindset intervention research shows a significant effect on enjoyment of, and identification with, for example, education (Aronson et al., 2002) and increased intrinsic value and interest in a particular field (e.g., computer science, Burnette et al., (2020a).

Mindsets, Efficacy, and Value in Entrepreneurship

A few early studies indicate that mindsets of entrepreneurship also relate to expectancy-value, with the majority of research into entrepreneurship focusing on self-efficacy (e.g., Pollack et al., 2012). More recent work extended prior findings by examining the influence of a growth mindset intervention (Burnette et al., 2020b) on not only self-efficacy but also on dimensions of value, including academic and career interest in entrepreneurship. Results showed that the growth mindset intervention indirectly increased interest in pursuing both future entrepreneurship coursework and a career as an entrepreneur, with these indirect effects driven by increased self-efficacy.

Mindsets and Cost Evaluations

Importantly, no extant studies have investigated a key dimension highlighted by expectancy-value theory—namely, whether a growth mindset might reduce the perceived costs of engaging in entrepreneurship (for a review see Renko et al., 2012). This represents a gaping lack of insight into an important aspect of research in this area of inquiry. In expectancy-value theory, cost is understood to be a dimension of value that subtracts from overall motivation by indexing the effort, forgone opportunities, and negative emotions (e.g., stress) associated with achieving a given end (Eccles, 2005; Flake et al., 2015; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). We aim to examine these four questions about growth mindsets and motivation:

Research Question 5: Is there a positive association between growth mindsets and entrepreneurial self-efficacy?

Research Question 6: Is there a positive association between growth mindsets and evaluations of entrepreneurship value (enjoyment, identity, and utility)?

Research Question 7: Is there a negative association between growth mindsets and the perceived costs of entrepreneurship?

Research Question 8: Are associations between entrepreneurial mindset and efficacy, value, or cost moderated by entrepreneurial status?

Methods

Participants Footnote 1

We recruited 800 participants (400 entrepreneurs, 400 non-entrepreneurs) through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Marketplace (MTurk), integrating best practices (e.g., attention checks, open-ended responses, CAPTCHA) for ensuring data quality (Cheung et al., 2017). Data from MTurk have been found to be high quality and appropriate for recruiting participants to provide insights on topics ranging in scope from marketing (e.g., Brcic & Latham, 2016), to organizational culture (e.g., Belmi & Pfeffer, 2015), to creativity (e.g., Loewenstein & Mueller, 2016), to entrepreneurship-related phenomena (e.g., Chan & Parhankangas, 2017; Gunia et al., 2021; Hubner et al., 2019). We compensated participants $0.50.

To recruit participants in both categories—entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs—we launched one online survey (via Qualtrics), that included branch logic. After consenting to participate in the online survey, participants were asked a series of screening questions: “Are you currently an entrepreneur?” (response options: no/yes); if no was selected on that first question, then, “Have you ever been an entrepreneur?” (response options: no/yes); and if no was selected on that second question, then, “Which of the following best describes you? (response options: “I have never really considered being an entrepreneur”; “I have considered being an entrepreneur, but decided not to”; “I’m actively considering being an entrepreneur”; “I used to be an entrepreneur”). After this, all participants filled out the measures described below. The survey was branched so that entrepreneurs received an additional set of questions that asked in what year their venture was started, and in what industry their venture is in. Of the 800 participants who completed the survey, 264 current entrepreneurs (Mage = 35.67, age range = 18–72, SD = 11.40) and 330 non-entrepreneurs (Mage = 39.58, age range = 18–78, SD = 14.20) provided complete data for analysis (see Consort Diagram, Fig. 1).

Measures

Consistent with best practices in the literature regarding transparency (e.g., Anderson et al., 2019; Maula & Stam, 2019), we have numerous files available on Open Science Framework (OSF; anonymized for review). Our data and measures can be found here: https://osf.io/gu4sc/?view_only=d3b1f3f480dd4a22ab8e6b74c35411ea). Also, please see Appendix A.

Mindsets

Participants completed five mindset scales, each with three items: mindsets of entrepreneurship (Burnette et al., 2020b; e.g., “I have a certain amount of entrepreneurial ability, and I can’t really do much to change it”, α = .93), leadership (Burnette et al., 2010; e.g., “To be honest, I can’t really change my ability to lead”, α = .87), creativity (Katz-Buonincontro et al., 2016; e.g., “Some people are creative, others aren’t—and no practice can change it”, α = .91), intelligence (Castella & Byrne, 2015; e.g., “I don’t think I personally can do much to increase my intelligence”, α = .91), and people (e.g., “People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed”, α = .93). All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Scores are coded so that higher scores indicate greater growth mindset.Footnote 2

Traits

Participants completed assessments of Big Five personality (Rammstedt & John, 2007) and three traits relevant to entrepreneurship, including risk-taking (Jackson, 1976; Murphy et al., 2019), resilience (Smith et al., 2008), and need for achievement (Chen et al., 2012; Robichaud et al., 2001). We assessed Big Five personality traits with eleven items. Due to low internal consistencies of the five expected personality dimensions (extraversion α = .54; agreeableness α = .54; conscientiousness α = .52; neuroticism α = .57; openness α = .28), we do not calculate composite scores for each dimension or employ them in regression analyses. Instead, we report the correlations of mindset with each individual item from the scale. We assessed risk-taking with ten items (e.g., “I enjoy being reckless”, α = .85). We assessed resilience with six items (e.g., “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”, α = .85). We assessed need for achievement with four items (e.g., “I need to prove that I can succeed”, α = .87). All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater presence of the trait.

Motivation: Efficacy, Value, and Cost

Participants completed assessments of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, value, and cost. We assessed entrepreneurial self-efficacy with four items (Zhao et al., 2005; e.g., “I am confident that I can identify new business opportunities”, α = .91). We assessed entrepreneurial value with ten items in total, based on a priori conceptualizations of value (Flake et al., 2015). A factor analysis revealed that our ten-item assessment of value reflected three dimensions, with enjoyment and utility items clustering together as a single factor measured with four items (e.g., “Being an entrepreneur is enjoyable” and “Being an entrepreneur could help me achieve other important goals in my life”, α = .88). Identity value was assessed with two items (e.g., “Being an entrepreneur is an important part of my identity”, α = .95). And cost was assessed with four items (e.g., “Being an entrepreneur demands too much time”, α = .87). All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). For the two dimensions of value, higher scores thus indicated greater value. For the cost dimension, higher scores indicated greater cost, and thus less value.

Moderator: Entrepreneurial Status

Participants indicated whether they identified as an entrepreneur (“Are you currently an entrepreneur”). Participants also reported demographics and additional information about their business if they identified as an entrepreneur (see Table 1 and OSF repositoryFootnote 3).

Data Analysis

The analytic plan for this paper followed the logic laid out in the research goals (1, 2, and 3) and associated research questions (1–8). Please see Appendix B for details concerning the methods and analyses used in each of the three major phases of the analysis, with an emphasis on taxometrics, as this is a relatively unfamiliar analytic procedure. All analyses were conducted using R Version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2017).

Results

Goal 1

Research Question 1: What Is the Latent Structure of Mindsets Relevant to Entrepreneurship?

Using an empirically estimated taxonic base rate of .41, the mean CCFI value was .412, which supports continuous rather than categorical latent structure. Specific CCFI values were as follows: MAXEIG = .35, L-Mode = .23, and MAMBAC = .52. Thus, two of the three approaches provided fairly strong support for a continuous latent structure, but the MAMBAC method was inconclusive. So, for Research Question 1, given the overall mean CCFI of .412, results suggest that the latent structure underlying the mindsets in entrepreneurship is continuous.

Research Question 2: How Many Dimensions Underlie Mindsets Relevant to Entrepreneurship?

The results generated from both an exploratory factor analysis as well as a confirmatory factor analysis led us to conclude that a unidimensional model captures the data best (see Appendix B as well as Tables 2, 3, and 4). We therefore tested a g-factor model on the full dataset, using item-level data. Results of this model are depicted in Fig. 2. We label the general factor “Growth Mindset in Entrepreneurship (GME),” and it is specified by each of the five mindset dimensions, with mindset of entrepreneurship setting the metric. All item-level loadings were above .80, and fit was good, robust χ2 (60) = 153.47, p < .001; robust CFI = .98; robust RMSEA = 0.065, 90% CI [0.05, 0.078]; SRMR = .035. Findings support the view—for Research Question 2—that a single dimension underlies these five growth mindsets.

Goal 2

Research Questions 3 & 4: Discriminant and Convergent Validity of GME

Correlations with the GME to specific items (see Table 5) ranged from nil (−.01 for the second extraversion item) to moderate in size (.44 for the first openness item). Answering Research Question 3, the GME was not consistently related to extraversion items, agreeableness items, or neuroticism items. However, growth mindset did display significant small positive associations with all items pertaining to conscientiousness (r’s = .34 and .15) and openness (r’s = .44 and .15). The specific conscientiousness and openness items with the strongest correlations to mindset index hard work and artistic interests, respectively. The former association and largest (i.e., mindset to hard work) is consistent with suggestions from mindset theory that growth mindset promotes greater effort, especially in the face of challenge (Burnette et al., 2013a, b; Rege et al., 2020).

Answering Research Question 4, for convergent validity (results are displayed in Table 6), as expected, growth mindset exhibited a significant positive association with self-reported resilience, r = .32, p < .001. The GME likewise exhibited the expected positive association with need for achievement, r = .19, p < .001. Contrary to expectations, GME displayed a significant negative correlation with propensity for risk-taking, r = −.12, p = .004.

Goal 3

Research Questions 5–7: Does GME Predict Expectancy-Value, Including Cost Evaluations?

Zero-order correlations are available in Table 6. To answer this question in a more robust fashion, we constructed linear regression models in which growth mindset was regressed on each dimension of expectancy-value motivation separately, while controlling for risk, resilience, and need for achievement (Table 7).

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

Answering Research Question 5, GME did not show much of an association with self-efficacy at the zero-order level, r = .07. When controlling for risk, resilience, and need for achievement, there was no effect, b = −.005, se = 0.04, p = .886. Thus, for Research Question 3, we observe no evidence of a relation between GME and efficacy.

Enjoyment/Utility

Answering Research Question 6, there was no significant correlation of GME with enjoyment/utility at the zero-order level, r = .00. When controlling for risk, resilience, and need for achievement, growth mindset was significantly associated with the enjoyment/utility dimension of value, b = −0.081, se = 0.034, p = .016. The effect, however, was negligible: increase in adjusted R-squared compared to model with all three controls was .005. In addition, the parameter estimate for GME was negatively signed, which would indicate that as mindset becomes more growth-oriented, value decreases—suggesting that mindsets do not directly relate as expected to enjoyment-utility value evaluations.

Identity Value

GME was significantly associated with identity value, after controlling for risk, resilience, and need for achievement, b = −0.26, se = 0.05, p < .001. Increase in adjusted R-squared compared to the model with all three controls was .026, with the overall model accounting for 31% of variance. Directionality of the relationship was negative, indicating that as growth mindset increases, identity value decreases. This negative association was also observed at the zero-order level, r = −.14. These findings are opposite of what we expected.

Cost

As Table 6 indicates, GME exhibited a moderately strong zero-order correlation with the cost dimension of value, r = −.40. The association held when controlling for risk, resilience, and need for achievement, b = −0.38, se = 0.04, p < .001. Adjusted R-squared doubled with the addition of GME, from .105 to .208. Here, as GME increases, perception of costs to entrepreneurship decreases as well, consistent with growth mindset theory and providing an affirmative answer to Research Question 7.

Research Question 8: Does Entrepreneurial Status Moderate the Association of GME with Expectancy-Value?

To address this question, we constructed a series of linear regression models, separately for each dimension of expectancy-value. For each dimension, we first constructed a model that regressed the outcome only on GME. Then, we added entrepreneurial status as a moderator, with status operationalized as past/present entrepreneurs versus all others.

Self-Efficacy

Although there was no significant zero-order association of GME with self-efficacy, a significant association emerged when controlling for entrepreneurial status, b = 0.13, se = 0.04, p < .001, adjusted R-square = .290, such that greater GME was linked with greater self-efficacy, as expected. When the interaction term was entered into the model, the interaction was significant, b = −0.19, se = 0.08, p = .012, with adjusted R-squared of .297. In this interaction, the effect of GME was significant among non-entrepreneurs, such that each unit increase in GME was associated with a .23-unit increase in entrepreneurial self-efficacy (p < .001). However, among entrepreneurs, GME was not significantly associated with entrepreneurial self-efficacy, b = .04, se = 0.05, p = .439 (estimated from a reparameterized model in which entrepreneurs were coded as 0 instead of 1).

Enjoyment/Utility

As already shown by the previous correlation results, GME did not exhibit a zero-order association with enjoyment/utility. Unsurprisingly, that held true when controlling for entrepreneurial status, b = 0.05, se = .03, p = .181. And, equally unsurprisingly, entrepreneurs displayed significantly more enjoyment of entrepreneurship than did non-entrepreneurs, b = 1.31, se = 0.10, p < .001. When the interaction between GME and entrepreneurial status was entered into the model, the interaction was marginally significant, b = 0.13, se = 0.07, p = .060. For this interaction, the effect of mindset on interest/utility was significant and positive among entrepreneurs (b = 0.11, se = 0.05, p = .024), but non-significant among participants who were not entrepreneurs (b = −0.02, se = 0.05. p = .631). Overall, however, the interaction effect was trivial, with adjusted R-squared increasing only by .003 with inclusion of the interaction (from .229 to .232).

Identity Value

GME exhibited a small, but significant, zero-order association with identity value, b = −0.21, se = 0.06, p = .001, with an adjusted R-squared of .02. Entering entrepreneurial status into the model, we found that the association held, albeit with a smaller coefficient, b = −0.12, se = 0.04, p = .008. Not surprisingly, there was a huge effect of entrepreneurial status on identity value, b = 2.78, se = 0.13, p < .001, adjusted R-squared = .460. When the interaction between GME and entrepreneurial status was entered into the model, the interaction was significant, b = 0.36, se = 0.09, p < .001, adjusted R-squared = 0.473. This model indicates that the effect of GME was significant among non-entrepreneurs, such that each unit increase in growth mindset was associated with a .31-unit reduction in identity value (b = −.31. se = 0.07, p < .001). Among entrepreneurs, the effect of mindset on value-identity was non-significant, b = .04, se = 0.06, p = .473.

Cost

As shown earlier, GME was significantly associated with cost at the zero-order level, b = −0.433, se = 0.04, p < .001, adjusted R-squared = .15. Controlling for entrepreneurship, status this relationship held (b = −0.46, se = 0.04, p < .001), with entrepreneurship status exerting a sizeable effect (b = −.91, se = 0.11, p < .001), and overall adjusted R-squared increasing to .240. When we included the interaction in the model, the interaction was significant, b = −.38, se = 0.08, p < .001, and the overall adjusted R-squared rose to .269. The interaction indicates that the negative effect of GME on the costs of entrepreneurship is even stronger (more negative) among entrepreneurs than non-entrepreneurs. For non-entrepreneurs, the effect of growth mindset was significant (p < .001), such that each unit increase in GME was associated with a .26-unit reduction in the costs linked to entrepreneurship (b = −0.26, se = 0.06, p < −.001). But for entrepreneurs, this effect was nearly two-and-a-half times the magnitude, b = −.64, se = 0.05, p < .001.

Exploratory Question 1: Is GME Indirectly Linked to Value Via Self-Efficacy among Non-Entrepreneurs but Not among Entrepreneurs?

In answering Research Question 5, we failed to find a significant overall positive association between GME and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. This was somewhat surprising in light of results recently reported by Burnette et al. (2020b), who found that a growth mindset intervention increased entrepreneurial self-efficacy in an undergraduate sample, and that this elevated self-efficacy in turn served as a pathway through which growth mindset indirectly increased interest in entrepreneurship. In answering Research Question 8, however, we found that the effect of GME on self-efficacy was moderated by entrepreneurial status, such that a positive association of GME with self-efficacy was in fact observed—but only among non-entrepreneurs, rather than entrepreneurs. The conjunction of these findings suggests a possible means of reconciling the seeming discrepancy with prior results: perhaps GME exerts an indirect effect on the dimensions of value via self-efficacy—as found in Burnette et al. (2020b)—but only among non-entrepreneurs. After all, Burnette et al. (2020b) sampled students, not entrepreneurs.

To explore the possibility that the indirect effect of GME upon value via self-efficacy is conditional based upon entrepreneurial status, we examined a series of moderated mediation models. Specifically, we constructed moderated mediation models in which GME predicted each of the three value-related outcomes: Identity Value, Interest/Enjoyment, and Cost. As shown in Fig. 3, in each model, entrepreneurial status was allowed to moderate all three outcomes: mindset on self-efficacy, self-efficacy on value, and the direct effect of mindset on value (controlling for self-efficacy). And in all models, self-efficacy mediated the effect of GME on the ultimate value-based outcome.

For each of the three dimensions of value, there was a significant indirect effect of GME via self-efficacy in the hypothesized direction—for non-entrepreneurs only. Indirect effects for non-entrepreneurs, with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals, were as follows: for Identity Value, ab = 0.15, 95% CI [0.05, 0.26]; for Interest/Enjoyment, ab = 0.11, 95% CI [0.04, 0.18]; for Cost, ab = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.01]. These results are thus consistent with the view that, among non-entrepreneurs, GME fosters identity value and interest/enjoyment of entrepreneurship via an increased sense of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, while reducing the perceived costs of entrepreneurship via the same pathway. No such indirect effects were found among entrepreneurs, and the differences between indirect effects for entrepreneurs versus non-entrepreneurs were statistically significant for each outcome.Footnote 4 Altogether, the results of this exploration appear to replicate Burnette et al. (2020b) but indicate that the pattern may not generalize to actual entrepreneurs, as opposed to non-entrepreneurs who are students.

Exploratory Question 2: Is GME Associated with Entrepreneurial Status?

Recent developments from the mindset literature suggest that the links between growth mindset and distal achievement outcomes are often elusive and highly context-dependent. Meta-analyses such as Sisk et al. (2018) highlight this emergent conclusion (e.g., with distal outcomes in the academic domain). And, extant theory (from the organizational training literature—Kirkpatrick, 1959; Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006) and evidence suggest that more proximate outcomes—such as motivation and challenge-seeking behavior in such domains as academics, mental health, and social functioning—may be more reliable targets. Thus, we deliberately elected not to prioritize as a pre-registered goal of this study the distal question of whether or not growth mindsets predict being an entrepreneur (and thus, by proxy, venture creation). Nonetheless, we examine the issue here on an exploratory basis, and in doing so offer initial findings relevant to a question not yet (to our knowledge) examined empirically in the research literature.

As shown in Table 1, results indicate that the correlation of growth mindset in entrepreneurship with entrepreneurial status is r = −.10 and is statistically significant. Such an effect size is equivalent to a Cohen’s d of .20 (Lenhard & Lenhard, 2016), which indicates that entrepreneurs exhibit a more fixed mindset than non-entrepreneurs by approximately one-fifth of a standard deviation.

Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

In regard to the first goal, the assessment of growth mindsets in entrepreneurship, we first conducted taxometric analyses, which provided statistical evidence that the latent structure of mindset constructs related to entrepreneurship is continuous rather than categorical. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of its kind in the growth mindset literature. The finding that the latent structure of mindset constructs is continuous provides a formal statistical warrant for use of factor analyses. And, this result is quite plausible in light of a confluence of findings from taxometric investigations—which suggest that continuous latent constructs are susceptible to minor shifts via manipulation (Ruscio et al., 2006)—and mindset intervention research—which demonstrates that light-touch interventions indeed can produce modest shifts in mindsets in multiple domains (Burnette et al., 2020a, b; Sisk et al., 2018).

Practically speaking, our insights here might provide a lens through which greater nuance can be observed regarding the process by which a part-time entrepreneur becomes a full-time entrepreneur, or by which someone who pursues a hobby turns it into an identity and a business (e.g., Audretsch et al., 2017). Put simply, it could be that someone who has a greater growth mindset of entrepreneurship (see our validated measures in Appendix A) is more likely to make the transition—and now we can measure it. And, since we know that mindsets can be taught or primed, interventions along these lines can facilitate greater entrepreneurial entry from accelerators, incubators, and other settings in which aspiring entrepreneurs have to consider how to assess the pitfalls of startup life (e.g., Bullough et al., 2014) and make (or not) the jump to full-time entrepreneurship.

We next conducted factor analyses to better understand the nature of growth mindsets that are relevant for entrepreneurship. We found evidence of a unidimensional growth mindset in entrepreneurship (GME) that underlies the five mindset constructs relevant to being an entrepreneur (mindsets of entrepreneurship, mindsets of leadership, person mindsets, mindsets of intelligence, and mindsets of creativity). This finding suggests that interventions, trainings, or curricula aimed at fostering stronger growth mindsets of entrepreneurship might consider simultaneously including multiple messages of change: information about the potential for the brain to make new connections; content concerning the potential to develop creativity and leadership skills; the idea that generally people can and do change with new experiences; and information about the potential to improve entrepreneurial abilities. This finding is entirely plausible in light of prior mindset research, which finds evidence of overlap in some mindsets, including intelligence and personality (Burnette et al., 2020a, b).

In terms of our second research goal, testing the personality correlates of mindsets, the unidimensional GME demonstrated small but significant positive correlations with standard indicators of conscientiousness and openness, but did not consistently correlate with indicators of extraversion, agreeableness, or neuroticism. Such findings are in accord with prior psychometric work on mindsets of intelligence and personality (Dweck et al., 1995). We also found that GME correlated significantly and positively with resilience and need for achievement but displayed a significant (and unexpected) negative correlation with risk-taking. These results suggest that GME is a distinct construct. That is, GME is largely unrelated to measures of Big Five personality but does display small to moderate correlations with related constructs of resilience and need for achievement. The positive relation between growth mindsets and resilience as well as the desire to master and learn new skills (i.e., need for achievement) is consistent with past work (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2015; Yeager & Dweck, 2012).

However, it is unclear why GME might be negatively related to risk-taking. One potential explanation is that, in the current work, we operationalized risk-taking at a dispositional level. Perhaps growth mindsets encourage seeking challenges related to learning and development in specific contexts but do not foster a general inclination towards danger and adventure. By contrast, a fixed mindset about one’s abilities might instigate a desire to prove oneself to others, and being daring is one way to meet this goal. Overall, the current findings continue to provide evidence that growth mindsets are not strongly or consistently linked to the Big Five but do relate to resilience and the desire to learn and master new things. However, more work is needed to understand relationships between growth mindsets and different conceptualizations of willingness to take risks and try new ventures.

Our third goal was to look at effects of growth mindsets on motivation. Past work, primarily with student samples, reports a positive association (Burnette et al., 2020b), whereas other work only finds a relation between growth mindsets and self-efficacy when threat is salient (Pollack et al., 2012). Our current study extends and qualifies extant findings by sampling both entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs, and by examining cost as an important dimension of value. The expected significant positive association of GME with self-efficacy emerged, but only among non-entrepreneurs. The lack of a positive association among entrepreneurs may be related to differences between entrepreneurs in threat salience (e.g., Pollack et al., 2012)—making this a worthwhile topic for future research, as we note later when addressing limitations and future directions. Additionally, among non-entrepreneurs, we find a significant indirect effect of GME on each dimension of value via self-efficacy, consistent with previous research (Burnette et al., 2020b).

With respect to direct links between mindset and value, our work highlights the important—and heretofore under-examined—role of cost as a dimension of value. Results revealed that GME displayed a significant negative association with the perceived costs of entrepreneurship. Additionally, this association was significant among both non-entrepreneurs and entrepreneurs but was significantly stronger among entrepreneurs. This was the largest and most robust outcome in the current work, and it held controlling for other relevant predictors. Although cost was introduced in the earliest formulations of the theory (Eccles et al., 1983), it languished in relative obscurity for over two decades, until a resurgence of interest re-established its relevance (for a review, see Flake et al., 2015). Yet, to date, cost as a dimension of expectancy-value has not been explicitly examined as a factor predicting entrepreneurial motivation (e.g., Renko et al., 2012). Our work addresses this issue and from a practical standpoint our findings suggest that fostering growth mindsets could reduce negative appraisals by reframing effort and work as progress. Indeed, a plethora of work highlights the importance of these evaluations for motivation to pursue goals, and this has particular relevance for the field of entrepreneurship where obstacles can be seen as opportunities or hindrances.

Contrary to expectations, there was no total effect of GME with enjoyment/utility conceptualizations of value, although there was a significant (albeit very small) positive association among entrepreneurs. Furthermore, there was a negative association of GME with identity value only for non-entrepreneurs. Among entrepreneurs, there was no significant association with identity-value. Overall, in considering how our findings match with past work on growth mindsets and expectancy-value outcomes in entrepreneurship, we find that entrepreneurial status is a critical moderator, with effects only replicating for self-efficacy in individuals who do not identify as an entrepreneur. Furthermore, we find little support for direct links between growth mindsets and value—at least when conceptualized as enjoyment, utility and identity. However, we do replicate past work that finds an indirect link between mindsets and value via self-efficacy—at least in the non-entrepreneurial sub-sample.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

First, our work is limited in that we recruited participants from the United States. Future work definitely needs to examine, for example, “how the exposure to foreign countries” can aide in developing entrepreneurial mindsets (Pidduck et al., 2020, p. 14). Second, we used MTurk, and we acknowledge that findings based on MTurk data should be replicated (e.g., Chmielewski & Kucker, 2020). Third, the current work is cross-sectional and correlational, thus limiting conclusions about the causal direction of effects (Sisk et al., 2018). Fourth, with regard to the mindset measures we used, we did not look specifically at how each individual measure affected motivation. Because we did not have a theoretically-driven reason for why one, versus another, mindset measure would differentially predict motivation, using one parsimonious growth mindset measure may increase replicability and be more likely to generalize (e.g., Burnette et al., 2020b; Costello & Osborne, 2005). Fifth, we did not differentiate our sample of entrepreneurs based on what stage of venturing, or type of venture, they were in (e.g., nascent, emerging, growth, established, prosocial, antisocial; Lundmark & Westelius, 2019). For example, there is evidence to suggest that entrepreneurs at various organizational life cycle stages will experience unique events, challenges, and setbacks (Dibrell et al., 2011; Dodge & Robbins, 1992) and thus, this may further moderate links between mindsets and motivation. Relatedly, the association of mindsets and outcomes has been shown to be especially important when threat is salient (e.g., Pollack et al., 2012). So, looking at what challenges arise at different organizational life cycle stages, and how mindsets affect whether and how aspiring and emerging entrepreneurs react, and cope, is a very important topic for future research. Sixth, we operationalized motivation using expectancy-value theory. Although prominent in the research literature, expectancy-value theory is not the only conceptual framework available to address motivation. Future research might profitably examine the association of entrepreneurial mindsets and motivation using alternative models and operationalizations of motivation. Finally, on an exploratory basis, we examined whether growth mindset in entrepreneurship was linked to entrepreneurial status. Counterintuitively, we found that non-entrepreneurs were more growth-oriented than entrepreneurs in their mindset. Such a finding may add to emergent results from the mindset literature suggesting that the links between growth mindset and distal achievement outcomes are tenuous and highly context-dependent. Future research, perhaps involving longitudinal designs, will be needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which growth mindsets might influence more proximate outcomes relevant to entrepreneurship, and perhaps, in turn and under some conditions, the concrete processes by which individuals become entrepreneurs and create ventures.

These limitations pave the way for future work to replicate and extend existing findings. For example, future research could investigate links in more diverse samples, utilize experimental designs, include entrepreneurs at different stages in their ventures, and incorporate other relevant outcomes such as how GME might affect identity and passion in entrepreneurship (Murnieks et al., 2020) as well as in actual startup decisions. Additionally, in the future it will be intriguing to examine if, and how, other personality factors, such as grit, affect important outcomes among entrepreneurs in concert with mindsets (Dixson, 2019).

Conclusion

We examined how beliefs about the malleable versus fixed nature of the attributes required to be an entrepreneur can be assessed in a statistically reliable way. We also explored if these mindsets are important predictors of motivation. In addition to providing a methodologically sound measure to assess growth mindsets of entrepreneurship, we leveraged the longstanding literature on growth mindsets to outline how mindsets relate to efficacy, value, and cost evaluations—all critical motivators and predictors of achievement. The findings point to the importance of understanding links in entrepreneurs as well as non-entrepreneurs and highlights the importance of growth mindsets for cost evaluations.

Data Availability

We have numerous files available on Open Science Framework (OSF; anonymized for review). Our data and measures can be found here: https://osf.io/gu4sc/?view_only=d3b1f3f480dd4a22ab8e6b74c35411ea.

Notes

Two items—one from the leadership scale and one from the intelligence scale—were deleted because their wording was directionally opposite that of the other 13 items, substantially reducing scale reliability (and in the case of the intelligence item, not exhibiting metric invariance across entrepreneurs vs. non-entrepreneurs).

OSF repository: https://osf.io/gu4sc/?view_only=d3b1f3f480dd4a22ab8e6b74c35411ea

Statistical significance for the difference in indirect effects was determined by examining the index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2018) in all three models. For each dimension of value, the index of moderated mediation significantly differed from zero based on bootstrapped confidence intervals (for Identity Value it was −0.13, 95% CI [−0.24, −0.01]; for Interest/Enjoyment: −.09, 95% CI [−0.17. -0.003]; for Cost: 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.10].

References

Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125.

Anderson, B. S., Wennberg, K., & McMullen, J. S. (2019). Enhancing quantitative theory-testing entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105928.

Audretsch, D. B., Obschonka, M., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2017). A new perspective on entrepreneurial regions: Linking cultural identity with latent and manifest entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 48(3), 681–697.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Belmi, P., & Pfeffer, J. (2015). How “organization” can weaken the norm of reciprocity: The effects of attributions for favors and a calculative mindset. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 36–57.

Borsboom, D., Rhemtulla, M., Cramer, A. O. J., van der Maas, H. L. J., Scheffer, M., & Dolan, C. V. (2016). Kinds versus continua: A review of psychometric approaches to uncover the structure of psychiatric constructs. Psychological Medicine, 46, 1567–1579.

Brcic, J., & Latham, G. (2016). The effect of priming affect on customer service satisfaction. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(4), 392–403.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd Ed. The Guilford Press.

Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self–efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499.

Burnette, J. L., Hoyt, C. L., Russell, V. M., Lawson, B., Dweck, C. S., & Finkel, E. (2020a). A growth mind-set intervention improves interest but not academic performance in the field of computer science. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(1), 107–116.

Burnette, J. L., O'Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., Forsyth, R. B., Hoyt, C. L., Babij, A. D., Thomas, F. N., & Coy, A. E. (2020b). A growth mindset intervention: Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and career development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(5), 878–909.

Burnette, J. L., Pollack, J. M., & Hoyt, C. L. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of leadership ability and self-efficacy: Predicting responses to stereotype threat. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(4), 46–56.

Chan, C. R., & Parhankangas, A. (2017). Crowdfunding innovative ideas: How incremental and radical innovativeness influence funding outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 237–263.

Carland III, J. W., Carland Jr., J. W., Carland, J. A. C., & Pearce, J. W. (1995). Risk taking propensity among entrepreneurs, small business owners and managers. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 15.

Chen, S., Ding, Y., & Liu, X. (2021). Development of the growth mindset scale: Evidence of structural validity, measurement model, direct and indirect effects in Chinese samples. Current Psychology, 1–15.

Chen, S., Su, X., & Wu, S. (2012). Need for achievement, education, and entrepreneurial risk-taking behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40(8), 1311–1318.

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(4), 347–361.

Chmielewski, M., & Kucker, S. C. (2020). An MTurk crisis? Shifts in data quality and the impact on study results. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 464–473.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical assessment, research, and evaluation, 10(1), 7.

Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Mayer, P. S. (2016). Developing a new measure of entrepreneurial mindset: Reliability, validity, and implications for practitioners. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(1), 21–48.

Dibrell, C., Craig, J., & Hansen, E. (2011). Natural environment, market orientation, and firm innovativeness: An organizational life cycle perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(3), 467–489.

Dixson, D. D. (2019). Is grit worth the investment? How grit compares to other psychosocial factors in predicting achievement Current Psychology, 1–8.

Dodge, H. R., & Robbins, J. E. (1992). An empirical investigation of the organizational life cycle. Journal of Small Business Management, 30(1), 27.

Donohoe, C., Topping, K., & Hannah, E. (2012). The impact of an online intervention (Brainology) on the mindset and resiliency of secondary school pupils: A preliminary mixed methods study. Educational Psychology, 32(5), 641–655.

Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (2000). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Key reading in social psychology. Motivational science: Social and personality perspectives (p. 394–415). Psychology Press.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. In A. S. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 105–121). The Guildford Press.

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., et al. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and sociological approaches (pp. 75–138). W.H. Freeman and Company.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191.

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244.

Flora, D. B. (2018). Statistical methods for the social and Behavioural sciences: A model-based approach. Sage Publication Ltd..

Gunia, B. C., Gish, J. J., & Mensmann, M. (2021). The weary founder: Sleep problems, ADHD-like tendencies, and entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 45(1), 175–210.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to moderation, mediation, and conditional process analysis , 2nd Ed. The Guilford Press.

Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229.

Hubner, S., Baum, M., & Frese, M. (2019). Contagion of entrepreneurial passion: Effects on employee outcomes. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1042258719883995.

Jackson, D. N. (1976). Jackson personality inventory manual. Research Psychologists Press.

Katz-Buonincontro, J., Hass, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2016). To create or not to create? That is the question: Students' beliefs about creativity. AERA Online Paper Repository.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1959). Techniques for evaluating training programs. Journal of the American Society of Training Directors, 13(11), 3–9.

Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., & Audretsch, D. B. (2020). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset. Small Business Economics, 1–11.

Lenhard, W. & Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of effect sizes. Retrieved from: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html. Dettelbach (Germany): Psychometrica. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Loewenstein, J., & Mueller, J. (2016). Implicit theories of creative ideas: How culture guides creativity assessments. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(4), 320–348.

Lundmark, E., & Westelius, A. (2019). Antisocial entrepreneurship: Conceptual foundations and a research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 11, e00104.

Maula, M., & Stam, W. (2019). Enhancing rigor in quantitative entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1042258719891388.

McGrath, R. G., MacMillan, I. C., & Scheinberg, S. (1992). Elitists, risk-takers, and rugged individualists? An exploratory analysis of cultural differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(2), 115–135.

Meehl, P. E. (1992). Factors and taxa, traits and types, differences of degree and differences in kind. Journal of Personality, 60, 117–174.

Murnieks, C. Y., Cardon, M. S., & Haynie, J. M. (2020). Fueling the fire: Examining identity centrality, affective interpersonal commitment and gender as drivers of entrepreneurial passion. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(1), 105909.

Murphy, P. J., Pollack, J., Nagy, B., Rutherford, M., & Coombes, S. (2019). Risk tolerance, legitimacy, and perspective: Navigating biases in social enterprise evaluations. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 9(4).

Orvidas, K., Burnette, J. L., & Russell, M. (2018). Mindsets applied to fitness: Growth beliefs predict exercise efficacy, value and frequency. Psychology of Sports and Exercise, 36, 156–161.

Pidduck, R. J., Busenitz, L. W., Zhang, Y., & Moulick, A. G. (2020). Oh, the places you’ll go: A schema theory perspective on cross-cultural experience and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00189.

Pollack, J. M., Burnette, J. L., & Hoyt, C. L. (2012). Self-efficacy in the face of threats to entrepreneurial success: Mindsets matter. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34, 287–294.

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212.

Rege, M., Hanselman, P., Solli, I. F., Dweck, C. S., Ludvigsen, S., Bettinger, E., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Walton, G., Duckworth, A., & Yeager, D. S. (2020). How can we inspire nations of learners? An investigation of growth mindset and challenge-seeking in two countries. American Psychologist, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000647

Renko, M., Kroeck, K. G., & Bullough, A. (2012). Expectancy theory and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 667–684.

Revelle, W. (2018). Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Northwestern University Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Robichaud, Y., McGraw, E., & Roger, A. (2001). Toward the development of a measuring instrument for entrepreneurial motivation. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 6, 189–201.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36 Retrieved from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Ruscio, J., Haslam, N., & Ruscio, A. M. (2006). Introduction to the Taxometric method: A practical guide (1st ed.). Routledge.

Ruscio, J., & Ruscio, A. M. (2004). A nontechnical introduction to the taxometric method. Understanding Statistics, 3, 151–194. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0303_2

Ruscio, J., & Wang, S. (2017). RTaxometrics: Taxometric analysis. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RTaxometrics. Accessed 15 Jun 2021.

Sakaluk, J. K. (2019). Expanding statistical frontiers in sexual science: Taxometric, invariance, and equivalence testing. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(4–5), 475–510.

Schmidt, J. A., Shumow, L., & Kackar-Cam, H. (2015). Exploring teacher effects for mindset intervention outcomes in seventh-grade science classes. Middle Grades Research Journal, 10(2), 17–32.

Shaver, K. G., Wegelin, J., & Commarmond, I. (2019). Assessing entrepreneurial mindset: Results for a new measure. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 10(2), 13–21.

Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200.

Sriram, R. (2014). Rethinking intelligence: The role of mindset in promoting success for academically high-risk students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 15(4), 515–536.

Stewart Jr., W. H., & Roth, P. L. (2001). Risk propensity differences between entrepreneurs and managers: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 145–153.

Thomas, F. N., Burnette, J. L., & Hoyt, C. L. (2019). Mindsets of health and healthy eating intentions. Journal of applied social psychology, 1-9.

Wang, D., Gan, L., & Wang, C. (2021). The effect of growth mindset on reasoning ability in Chinese adolescents and young adults: The moderating role of self-esteem. Current Psychology, 1–7.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272.

Code Availability

See online OSF files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors are listed in order of contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Approved by the Human Subjects Review Board at NC State University.

Consent to Participate

Was secured for each individual.

Consent for Publication

Granted.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from participants before they completed our online survey. This work was conducted in accordance with the IRB at NC State University, protocol #21000.

Conflict of Interest

No funding was received to assist in the preparation of this manuscript. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Appendix A. Measures

All items used the same 1–7 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Mindsets of Entrepreneurship

-

1.

I have a certain amount of entrepreneurial ability, and I can’t really do much to change it.

-

2.

My entrepreneurial ability is something about me that I can’t change very much.

-

3.

To be honest, I can’t really change my entrepreneurial ability.

Mindsets of Leadership

-

1.

I have a certain amount of leadership ability, and I can’t really do much to change it.

-

2.

To be honest, I can’t really change my ability to lead.

-

3.

Becoming a good leader takes time, effort, and energy.

Mindsets of Creativity

-

1.

I have a certain amount of creativity and I really can’t do much to change it.

-

2.

You either are creative or are not—even trying very hard you cannot change much.

-

3.

Some people are creative, others aren’t—and no practice can change it.

Mindsets of Intelligence

-

1.

I don’t think I personally can do much to increase my intelligence.

-

2.

To be honest, I don’t think I can really change how intelligent I am.

-

3.

With enough time and effort, I think I could significantly improve my intelligence level.

Mindsets of People

-

1.

People can do things differently, but the important parts of who they are can’t really be changed.

-

2.

The kind of person someone is is something very basic about them that can’t be changed very much.

-

3.

Everyone is a certain type of person, and there is not much that can be done to really change that.

Big Five

“ How well do the following statements describe your personality? I see myself as someone who...”

-

1.

...is reserved.

-

2.

...is generally trusting.

-

3.

...tends to be lazy.

-

4.

...is relaxed, handles stress well.

-

5.

...has few artistic interests.

-

6.

...is outgoing, sociable.

-

7.

...tends to find fault with others.

-

8.

...does a thorough job.

-

9.

...gets nervous easily.

-

10.

...has an active imagination.

-

11.

...is considerate and kind to almost everyone.

Risk Taking

“Using the scale below, please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

I enjoy being reckless.

-

2.

I take risks.

-

3.

I seek danger.

-

4.

I know how to get around the rules.

-

5.

I am willing to try anything once.

-

6.

I seek adventure.

-

7.

I would never go hang-gliding or bungee-jumping.

-

8.

I would never make a high-risk investment.

-

9.

I stick to the rules.

-

10.

I avoid dangerous situations.

Resilience

“Please indicate how accurately that trait describes you...”

-

1.

I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.

-

2.

I have a hard time making it through stressful events.

-

3.

It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event.

-

4.

It is hard for me to snap back when something bad happens.

-

5.

I usually come through difficult times with little trouble.

-

6.

I tend to take a long time to get over set-backs in my life.

Need for Achievement

“To what degree do you agree with the following four statements?”

-

1.

I need to meet the challenge.

-

2.

I need to continue learning.

-

3.

I need personal growth.

-

4.

I need to prove that I can succeed.

Self-Efficacy

“I am confident that I can…”

-

1.

Identify new business opportunities

-

2.

Create new products

-

3.

Think creatively

-

4.

Commercialize an idea or new development

Value- Enjoyment/Utility

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur is enjoyable.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is interesting.

-

3.

Being an entrepreneur could help me achieve other important goals in my life.

-

4.

Being an entrepreneur provides more opportunities than other career options.

Value- Identity

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur is an important part of my identity.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is important to who I am.

Cost

“Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements.”

-

1.

Being an entrepreneur demands too much time.

-

2.

Being an entrepreneur is too much work.

-

3.

I have so many other responsibilities that I am unable to put in the effort necessary to be an entrepreneur.

-

4.

Being an entrepreneur is too stressful.

Appendix B. Data Analysis

Goal 1

Research Question 1: Taxometric Analysis

Taxometrics is a quantitative analysis that assesses whether a set of observed scores reflects an underlying categorical latent variable or an underlying continuous latent variable (Borsboom et al., 2016; Meehl, 1992; Ruscio et al., 2006; Ruscio & Ruscio, 2004). It answers the question of whether observed scores are likely the product of latent discrete classes or profiles, on the one hand, versus continuous latent factors or dimensions, on the other. This conclusion, in turn, offers researchers guidance on the empirical techniques best suited for subsequent empirical investigation—that is, should researchers undertake latent class analysis (for categorical structures), or factor analysis (for continuous structures).

Taxometric analysis works by determining the fit of both latent categorical and latent continuous models to the observed data, then formally comparing these degrees of fit. This approach provides a quantitative index of how much better (or worse) a continuous measurement model captures the data, relative to a discrete measurement model. Specifically, and as implemented in the R package used here (RTaxometrics; Ruscio & Wang, 2017), the software simulates data assuming an ideal latent categorical structure, then simulates data assuming an ideal latent continuous structure, and then compares the fit of the observed data to each of the two simulated datasets. Fit of the observed data to each simulated dataset is measured using a variant of the Root Mean Squared Residual (RMSR). These two fit measures are then combined into a single index of relative fit, referred to as the Comparative Curve Fit Index (CCFI). The CCFI ranges from 0 to 1, with values substantially greater than .50 (.55 or higher) representing support for a latent categorical model, values substantially less than .50 (.45 or lower) representing support for a latent continuous model, and values near .50 indicating unclear results (Sakaluk, 2019). In practice, the above procedure is performed using three different specifications of “ideal” categorical and continuous latent structure (for details, see Ruscio & Wang, 2017), with a CCFI value generated for each approach (termed “MAMBAC,” “MAXEIG,” and “L-Mode,”, respectively), as well as an overall CCFI that averages all three outputs. In this way, researchers can determine whether multiple approaches converge on the same conclusion—either categorical or continuous latent structure (Ruscio et al., 2006).

In accordance with conventional recommendations (Ruscio & Wang, 2017), data were first checked to gauge their suitability for taxometric analysis (for data analytics overview). Data checks indicated no issues with skew or with item validities (discriminatory ability). Although some within-group correlations were above recommended levels for taxometrics, we proceeded with analyses.

For the present investigation, we entered composite scores for each of the five mindset scales—Entrepreneurship, Leadership, Creativity, Intelligence, and Personality—as continuous indicators into the taxometric analysis. In accord with the suggestions of Sakaluk (2019), a researcher-provided initial estimate of the taxonic base rate (a parameter necessary to simulate data under the assumption of idealized categorical structure) was used—in this case .25. This initial estimate allows CCFI values to be generated efficiently, during which process the software generates an empirically estimated taxonic base rate. The analysis was then re-run using the empirical estimate of the base rate.

Research Question 2: Factor Analysis

To determine the number of dimensions underlying growth mindsets of entrepreneurship, we conducted both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In order to improve generalizability of results, we randomly split the data into training and test datasets (N = 297 in each case), conducting exploratory factor analysis with the training data, and confirmatory factor analysis with the test data.

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the R package psych (Revelle, 2018). Number of factors was determined using a variety of criteria, including parallel analysis, root mean square residuals, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and interpretability of resulting factor loadings, in addition to Kaiser’s criterion and the scree plot. When multi-factor solutions were estimated, oblimin rotation was used, on the assumption that resulting factors were likely to correlate.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the R package lavaan (Rosseel, 2012). Model fit was assessed with the Chi-squared test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), RMSEA, and Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR). Robust versions of these criteria were employed when deviations from multivariate normality were indicated.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the training dataset. Given that each of the five mindset scales was had been previously validated, we entered composite scores for each scale (Flora, 2018). The strongest correlations occurred between entrepreneurship and leadership (.74) and between personality and creativity (.70). Inspection of a Normal Q-Q plot in conjunction with results of Mardia’s test suggested that the data could not be assumed multivariate normal. Accordingly, unweighted least squares estimation was used where possible.

Parallel analysis, inspection of a scree plot, and examination of eigenvalues in light of Kaiser’s criterion suggested the presence of either one or two factors (see Table 2). Therefore, we ran both a one-factor and a two-factor model for further examination. Because any two factors would likely be correlated (given than all variables represent facets of mindsets), oblimin rotation was used to interpret loadings.

Factor loadings for the one-factor model are provided in Table 3, for the two-factor model in Table 4. Additional criteria for distinguishing between the two models—beyond parallel analysis, a scree plot, and Kaiser’s criterion—were based upon Flora (2018), and included root mean square residuals (RMSR), visual inspection of the residual matrix, an exact-fit test, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and interpretation of factor loadings. Results are summarized in Table 2.

The one-factor solution accounted for 60% of variance, with all factor loadings greater than .50. RMSR was .04 and inspection of residual matrix revealed that all residuals were less than .10—both of which are consistent with good model fit. However, the exact-fit test was significant (p < .001), and the lower bound of the 90% confidence interval for RMSEA was > .10, with the latter finding in particular suggesting poor fit. A two- factor solution was estimated using unweighted least squares, but produced a Heywood case. A two-factor solution using maximum likelihood was then estimated and converged normally. Collectively, the two factors accounted for 69% of the variance, and overall exhibited notably better fit. The hypothesis of exact fit was not rejected (p = .67), RMSR was < .01, and the lower bound of the 90% confidence interval for RMSEA was 0. Interpretability, however, was not entirely clear. As Table 4 shows, mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together—which makes theoretical sense. But the loading for entrepreneurship was suspiciously high (and indeed was out-of-bounds using other forms of rotation). More worryingly, the remaining variables—intelligence, creativity, and personality—did not uniquely and strongly specify a single factor. Specifically, mindset of leadership showed signs of cross-loading (.39 on the “personality” factor, as well as .47 on the “entrepreneurship” factor). Additionally, the two factors correlated strongly (.70), but not above the threshold of .85, which is generally considered sufficient to conclude that the latent structure is unidimensional (Brown, 2015).

Altogether, the general better statistical fit of the two-factor model led us to slightly favor a two-factor structure in which mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together, but parsimony and interpretability kept us open to the possibility of a one-factor solution.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the test dataset. As with the EFA, composite scale scores for each mindset domain were used. Results of Mardia’s test again suggested that the data could not be assumed multivariate normal. Accordingly, models were estimated using robust maximum likelihood estimation (“MLM”).

A two-factor model was estimated, with the first factor consisting of mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership, and the second factor consisting of mindsets of creativity, intelligence and personality. For both factors, the metric of the latent was set by the mindset scale that loaded most strongly on the factor during the exploratory stage of analysis. Thus, mindset of entrepreneurship set the metric for Factor 1, and mindset of personality set the metric for Factor 2. Model estimation terminated normally. Fit of the model was good based on multiple major indices: robust χ2 (4) = .705, p = .951; robust CFI = 1.00; robust RMSEA = 0.00; SRMR = .008. All indicators loaded strongly on their assigned factors (> .70), but the two factors exhibited an extremely high correlation of .94. This correlation was well above the recommended threshold of .85 for concluding that two factors represent a single dimension.

Accordingly, a one-factor model was estimated with mindset of entrepreneurship setting the metric of the latent. Model estimation terminated normally. Fit of the one-factor model was also good based on the same major indices: robust χ2 (5) = 3.059, p = .691; robust CFI = 1.00; robust RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI [0.00, 0.09]; SRMR = .015. All indicators loaded strongly on the single factor (≥ .70).

The good fit of the one-factor model, together with the very high correlation of factors in the two-factor model, provided strong support for unidimensional latent structure, and additional evidence boosted this support. First, we estimated an alternative two-factor confirmatory model with a different pattern of loadings. Specifically, we assigned mindset of personality to load with the mindsets of entrepreneurship and leadership, rather than with creativity and leadership. Fit of this model was also excellent, χ2 (4) = 1.545, p = .819, indicating that the initial two-factor specification did not seem to be highlighting a particularly meaningful pattern of clustering. Second, using the test dataset, we repeated the exploratory factor analyses that we conducted earlier on the training dataset. Parallel analysis, inspection of a scree plot, and Kaiser’s criterion all suggested one rather than two factors. But most importantly, a two-factor EFA using the test data failed to yield the same pattern that was observed with the training data, in which entrepreneurship and leadership clustered together in one factor, while creativity, intelligence, and personality clustered in another. Indeed, with the test data, there was no interpretable second factor at all—factor loadings for the second factor were uniformly below .30. Thus, EFA results for a two-factor solution from the test dataset did not replicate those from the training dataset.

Goal 2

Research Questions 3 & 4: Correlation Analyses

To examine discriminant validity, we first report correlations of mindsets with each of the items in the Big Five. For convergent validity, we report correlations of mindsets with the three traits associated with successful entrepreneurship—namely, risk-taking, resilience and need for achievement.

Goal 3

Research Questions 5–8: Regression Analyses