Abstract

Different countries have exhibited dissimilar levels of adoption of IR. Yet, we still do not know why some countries enjoy more competitive advantage than others in IR adoption. The chapter addresses this gap by selecting Sri Lanka, a country which exhibits a high rate of adopting IR, to explain the national competitive advantage in its readiness for IR adoption. The chapter draws on its theoretical framing of Porter’s Diamond Theory. Ample availability of professional accountants, mounting stakeholder demands, a supportive accounting profession and intense competition among organizations aided by award schemes play a key role in propelling Sri Lanka towards a high adoption level of IR. Authors also identify the national culture of the country plays a key role in this process. In addition to its theoretical contributions, this chapter also sheds light on important implications for local and international institutions, policy makers, and various professions in identifying the requisite conditions for promoting new managerial tools and techniques such as IR or sustainability reporting (SR).

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Accounting tools

- Diamond theory

- Integrated reporting

- National competitive advantage

- National culture

- Sri Lanka

1 Introduction

Society’s growing awareness of environmental , social and governance issues has transformed the way a business is conducted (Kolk and Van Tulder 2010; Seuring and Muller 2008). Due to the magnitude of corporate activities, businesses have a broader responsibility to meet the aspirations of all its stakeholders – both current and future generations. This extended view on corporate responsibility has led to an improvement in environment, social and governance (ESG ) disclosures provided by companies. However, there were concerns as to whether the improvement in ESG disclosures of corporate entities reflects their integrated performance (Baron 2014; Lodhia 2015). These concerns have created a need to bring together the financial and ESG aspects of a company’s performance in a single report to integrate ESG components into the company’s strategy. This has led to the development of IR, which integrates SR more closely with financial reporting and governance reporting of an entity (refer Appendix 1 to see how the three pillars of sustainability are linked to the six capitals in IR). By identifying different types of capitals IR, is focused on the value creation process of an entity (International Integrated Reporting Council, IIRC 2013). In the recent years, IR has been fast diffusing as a new managerial technology. Reflecting this trend there are now many studies that focus on various aspects related to the adoption of IR. However, these studies do not provide a systematic explanation of why countries display different rates of adoption. Since the available studies on IR have mainly focused on developed countries (Jensen and Berg 2012), our understanding is incomplete without a sufficient knowledge of emerging economies. In this context, this chapter focuses on how a South Asian Country in the Asia Pacific Region has successfully moved towards integrated reporting (IR) , which enhances the way corporate entities think and report the story of their business.

The country selected for this purpose is Sri Lanka , which has a long history dating back to 543 BC (de Silva 2014). Sri Lanka is a country that has recognized the importance of sustainable development from ancient times embracing integrated thinking and accountability (Weeramantry 2002). The sophisticated irrigation systems constructed during the ancient kingdoms of Sri Lanka, which were even admired by the British who ruled the country from 1815 to 1948 as a remarkable achievement, were an embodiment of integrated thinking, sustainability and accountability (Bailey and Tennent as cited in de Silva 2014). Over the years, Sri Lanka has become a hub of accountants in Asia exporting its accountants to Australasia, Middle East and Africa (Senarathne and Gunarathne 2017). Moreover, according to the World Bank (2015) report on ‘Observance of Standards and Codes on Accounting and Auditing’, Sri Lanka has always shown a keen interest in the improvement of its accounting and auditing practices. Reflecting this interest, many Sri Lankan companies have embraced SR and IR on a voluntary basis though they have not yet been mandated in the country (World Bank 2015). Further, it indicates that these companies have implemented their policies, governance structures and monitoring mechanisms to comply with Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines on SR. This claim is also supported by the findings of studies of Dissanayake et al. (2016), Gunarathne and Alahakoon (2016) and Abeydeera et al. (2016b). As identified in the World Bank report, some Sri Lankan companies had started to provide an Integrated Report even before the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) issued the Framework on IR with one companyFootnote 1 joining its pilot project. Further, the adoption of IR in Sri Lanka is at the diffusionFootnote 2 stage and hence there will be many adopters in the future (Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017). These factors highlight that Sri Lanka is a unique case for exploring how it displays competitive advantage in adopting IR. This uniqueness is discussed in this chapter based on Porter’s Diamond Framework, which has been extensively used in the management literature as a theory that explains the international competitiveness of countries. This theory is described in detailed in Sect. 3.3.

The required data was collected from multiple sources, which include discussions, participation in forums, experiences of the authors and available rich literature. The authors held discussions with the relevant officials of companies engaged in SR and/or IR, assurance providers on SR, and representatives of PABs. These discussions were used to identify the factors that have motivated Sri Lankan companies to engage in SR and IR, the systems that they have established in this respect and the challenges faced. Further, the authors participated in several workshops on SR and IR conducted in Sri Lanka and sometimes even as panelists. In addition, both authors have served as judges of Institute of Certified Management Accountants of Sri Lanka (CMA) Excellence in IR Awards held in 2015. One of the authors participated in the evaluation committee of Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka (CASL) for its first ever IR awards held in 2014 and in the panel of judges of Association for Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) Sustainability Reporting Awards 2015. Moreover, the authors have also drawn insights in developing this chapter from their research studies carried out in Sri Lanka on SR and IR.

The subsequent sections of this chapter are organized as follows: Sect. 3.2 provides a review of extant literature on IR, while the subsequent section presents the Diamond Theory of Porter (1990). Section 3.4 presents the application of Porter’s Diamond Theory in order to illustrate how and why Sri Lanka displays a high level of IR adoption rate. The last Section presents the conclusions and the contributions of the chapter to accounting practices.

2 Integrated Reporting

In this section, the extant literature on IR is reviewed under three broad headings: emergence of IR; concept of IR; and state of IR around the world.

2.1 Emergence of IR

Corporate reporting has undergone a dramatic transformation over time with the broadening of the accountability of companies to diverse group of stakeholders inclusive of the environment and society at large. Post et al. (2002) in their book Redefining Corporation explain this extended accountability as follows:

The modern corporation is the centre of a network of interdependent interests and constituents each contributing (voluntarily or involuntarily) to its performance, and each anticipating benefits (or at least no uncompensated harms) as a result of the corporation’s activities (p. 8).

This has led corporate entities to report on areas such as governance, risk management and sustainability in addition to their financial performance (Eccles and Serafeim 2011; Gray et al. 2001; KPMG 2008; Owen 2006). As a result, new forms of reporting such as social and environmental reporting , triple bottom line reporting, and SR have been developed (Eccles and Krzus 2010) under the broad heading of social responsibility reporting, which has led to a substantial increase in non-financial reporting by corporate entities (Van Staden and Wild 2013).

Despite these efforts, concerns have been raised as to whether clear information on the strategy, governance, performance and prospects of a company is reported to its stakeholders (Van Staden and Wild 2013). This discussion grew with the mega corporate scandals in many parts of the world in recent times causing much economic and social turmoil. As a result, the need arose to develop a reporting model that could combine different strands of corporate reporting, namely, financial, governance, and sustainability, into a coherent whole to explain an organization’s ability to create and sustain value (Eccles and Krzus 2010). This provided the impetus for the emergence of IR as a new area of policy and practice in corporate reporting reflecting ‘integrated thinking’, and how value is created and sustained within an organization. Simnett and Huggins (2015) argue that prior to the advent of IR, there was no reporting framework by which companies could communicate their value-creation story across different time frames to interested stakeholders. IR, a contemporary managerial technology,Footnote 3 drives organizational change towards more sustainable outcomes (Eccles and Krzus 2010).

The pioneering work towards IR was made by the Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk in 2002 and the King III Report prepared in 2009, officially named as King Code of Governance Principles for South Africa (IoDSA and King III 2009), under the leadership of Professor Mervyn King, who championed the cause of IR in South Africa. Novozymes, a Danish enzyme company, spun off from Novo Nordisk in 2000, produced the first corporate integrated report in 2002 and Novo Nordisk began IR shortly thereafter (Eccles and Krzus 2010). Since then, Novo Nordisk has become a leader in the quest to measure and report social, environmental and financial performance within a single document (de Villars et al. 2014). This was followed by several Danish, US and Brazilian companies issuing integrated reports during the period from 2004 to 2008 (Eccles and Saltzman 2011). Even though these companies varied in terms of industry and geographical diversity, their reasons for issuing integrated reports are similar and are linked with their commitment to sustainability, which is defined broadly in financial and ESG terms. These companies had identified that an integrated report was the best way to communicate to stakeholders how well a company was accomplishing these objectives; and recognized that IR is an important discipline for ensuring that a company had a sustainable strategy. On the other hand, King III urged organizations to commit to the principles of integrated thinking, promoting the concept that strategy, governance and sustainability are intimately intertwined. These principles were subsequently incorporated into the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, requiring the listed companies to file an integrated report or explain why they were not doing so.

However, IR rapidly gained prominence globally with the formation of IIRC in 2010Footnote 4 with its mission to create a globally accepted framework on IR bringing together financial and ESG information of organizations into a clear, concise, consistent and comparable format (IIRC 2013). The International <IR> Framework of IIRC , the first complete globally accepted framework on IR, was published in 2013. Since then over 100 organizations have become a part of the IIRC pilot program for reporters, whose aim is to provide an opportunity to discuss and challenge technical material, test its application, and share learning and experiences (IIRC 2014).

2.2 The Concept of IR

IR is a process that focuses on how an organization creates value in the short, medium and long term. Hence, it combines different strands of corporate reporting (e.g. financial reporting- FR), governance reporting and SR into a coherent whole that explains an organization’s ability to create and sustain value. Thus, IR combines two traditions of corporate reporting – FR and SR. FR views a firm as a “nexus of contracts” among boards, managers, employees, suppliers and other actors, whose core purpose is to maximize returns to investors (Jensen and Mackling 1976). Conversely, SR provides a broader concept of a firm as a community of interdependent stakeholders who come together to create value as a collectivity (Sison 2010). Combining these two views, IIRC (2011) describes IR as follows:

Integrated Reporting brings together the material information about an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects in a way that reflects the commercial, social and environmental context within which it operates. It provides a clear and concise representation of how an organization demonstrates stewardship and how it creates value, now and in the future. Integrated Reporting combines the most material elements of information currently reported in separate reporting strands (financial, management commentary, governance and remuneration, and sustainability) in a coherent whole, and importantly:

Shows the connectivity between them; and

Explains how they affect the ability of an organization to create and sustain value in the short, medium and long term (p. 3).

However, developing an IR approach within a company requires ‘integrated thinking’ to identify the connectivity between different facets of a company that contribute to creating value and complexity in its value creation process. Eccles and Krzus (2010) developed integrated thinking in line with their concept of ‘One Report’, which has become synonymous with IR. They describe the concept of ‘One Report’ as producing a single report that combines the financial information of a company with its non-financial information (such as environmental, social and governance issues) showing their impact on each other. They also propose that ‘One Report’ can help to shift the focus of an organization from short-term financial goals to long-term business strategy that encourages commitment to corporate social responsibility and to a sustainable society as well.

Further, Stent and Dowler (2015) identify that integrated thinking, which is the process central to IR, is concerned with a higher level of thinking, decision making and reporting processes, in contrast to superficial compliance with mandatory requirements to produce corporate reports. He finds significant parallels between IIRC ’s concept of “integrated thinking” and the systems thinking paradigm. Hence, it is through this process of integrated thinking that a company is able to create and sustain value.

IIRC (2013) distinguishes between IR (the process) and an integrated report (the end product of the process). In the IIRC <IR> Framework, an integrated report provides concise communication about how an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects, in the context of its external environment, lead to the creation of value over the short, medium and long term. Hence, an integrated report should explain how an organization creates value. The value is not created by or within an organization alone. It is influenced by the external environment, is created through relationships with stakeholders and is dependent on various resources. Thus, the integrated report of a company is required to provide insights into the following aspects:

-

(a)

The external environment that affects the company;

-

(b)

The resources and the relationships used and affected by the company, which are referred to collectively as capitals under six categories: Financial, Manufactured, Intellectual, Human, Social and Relationship, and Natural (Refer Table 3.1).

-

(c)

The way the company interacts with the external environment and the capitals to create value over the short, medium and long term.

The accounting profession considers that the movement towards IR potentially represents the most significant change to the corporate reporting seen in years (Deloitte 2012) and its benefits have been considered in the academic literature. Eccles and Krzus (2010) classify the benefits of IR under two classes: internal benefits and external market benefits, where the former refers to better allocation of internal resources, greater engagement with stakeholders and lower reputational risk whilst the latter refers to meeting the needs of investors who require ESG information, appearing on sustainability indices, and ensuring data vendors report accurate non-financial information of a company. Eccles and Armbrester (2011) extend these benefits to include a third class of benefits termed managing regulatory risk covering the preparation for global regulations on IR and responding to local stock exchange requirements to report on IR.

2.3 State of IR Around the World

Companies are at varying stages in their path towards integration of different facets of reporting in moving towards IR, as revealed in the survey of ACCA and Net Balance Foundation (2011) in ASX 50 companies. The study carried out by Jensen and Berg (2012) reveals that there are several country-level determinants of IR such as investor and employment protection laws, intensity of market coordination and ownership concentration, the level of economic, environmental and social development, degree of national corporate responsibility and the value system of the country of origin. However, more recent studies show that IR is gaining momentum as a reporting model. The survey carried out by KPMG in Japan reveals that the number of Japanese companies that have prepared integrated reports in 2014 has considerably increased (i.e. by 38%) compared to that of 2013 and 26% of these companies have made explicit reference to the IIRC Framework. Further, 42% of these companies have presented their business models with 41% of them making reference to capitals identified in the IIRC Framework (KPMG 2015). Nevertheless, there are impediments to adopting an IR reporting model. Stent and Dowler (2015), providing early evidence of the changes required for current corporate reporting in New Zealand in terms of the IR Framework requirements, observe a gap between IR requirements and current best practice reporting processes. The study finds that common deficiencies that contribute to this gap include failing to: integrate reporting processes and to provide for oversight of these processes; report against regional/industry benchmarks; and to report on uncertainties in the future outlook of the entities concerned.

On the other hand, several studies have addressed the potential of reporting practices employed by the early adopters of IR to promote the transition to sustainable business practices. Stubbs and Higgins (2014), who investigated the internal mechanism employed by early adopters of IR in Australia , find that these organizations have changed or claimed to have changed their processes and structures; they have not necessarily stimulated new innovations in disclosure mechanisms. Hence, this study suggests that currently IR represents rather a transition from SR than an innovation driving transformation in organizations. Higgins et al. (2014) examined the business organizations in Australia that were the first to adopt IR, drawing from institutional theory to explain how early adopters made sense of IR. They suggest that the institutionalization of IR is unfolding and that isomorphism is likely to follow. However, this study also shares the view that this process is unlikely to deliver a fundamental change to organizational operations. While most of these studies are limited to developed countries, in the Sri Lankan context, Gunarathne and Senaratne (2017) find that IR adoption is at a diffusion stage with the number of companies that have adopted IR increasing rapidly from two companies in 2011 to 32 by the end of 2014. Further, Gunarathne and Senaratne (2017) find that the early adopting companies of IR in Sri Lanka had also been engaged in SR in the past. These companies are characterized by their integrated business models, a progressive work culture and the supportive role extended by the top management for adopting managerial innovations. The study also finds a transitional approach to IR in these companies evolving through incremental changes to systems and processes that are already established in them in relation to SR. This reflects a similar pattern to that observed by Stubbs and Higgins (2014) in Australia.

Further, Brown and Dillard (2014) critically assess IR to broaden the dialogue on how accounting and reporting standards assist or hinder efforts to foster sustainable business practices. In their study, they criticize the IIRC proposals stating that they offer few critical insights into the current ways of thinking, acting and reporting. Thus, drawing on natural science and technology research, they present the ways in which IR can be rearticulated. Further, Simnett and Huggins (2015) provide insights and details of the process of adoption of IR with implications for adopters and assurance providers of integrated reports, standard setters and regulators. They argue that in the early stages of the International <IR> Framework, there is a need and desire for corporate decisions to be based on a high quality and appropriate evidence base. This indicates that any business case for either regulatory initiatives or individual entity decision-making should be informed by high-quality research. Hence, the studies on IR in general have provided insights into the thinking, policy and practices around IR in different countries posing many interesting issues for further investigation in future studies. In this context, this chapter attempts to address how an Asian Pacific country displays competitive advantage in adopting IR using Porter’s Diamond Theory.

3 Porter’s Diamond Theory

Porter’s (1990) Diamond Theory suggests several important determinants of a nation’s global competitiveness. This model cleverly integrates the important variables that determine a nation’s competitiveness into one model while most of the other models are not comprehensive models (Moon et al. 1998). Porter’s model has been widely used to analyze a country’s competitive advantage , in general, or the global competitiveness of industries (Bellak and Weiss 1993; Cartwright 1993; Clancy et al. 2001; Curran 2000; Hodgetts 1993; Moon et al. 1998; Sardy and Fetscherin 2009; Sledge 2005; Zhaoa et al. 2011). According to Porter (1990), the ability to derive advantages in international trade and sustain them is not a cause, but an effect. Porter is of the view that a nation is most likely to be successful in industries when the national ‘diamond’ is the most favorable. The Diamond Theory has four broad interrelated attributes, namely, (a) factor conditions; (b) demand conditions, (c) related and supporting industries, and (d) firm strategy, structure, and rivalry (refer Fig. 3.1). He further suggests that government and chance events act as exogenous parameters of the model.

Determinants of national competitive advantage (Source: Porter 1990, p. 72)

3.1 Factor Conditions

Every nation possesses factors of production – the inputs necessary for competing in any industry such as labor, land, natural resources and infrastructure. These factors can be grouped broadly into human resources , physical resources, knowledge resources (in universities, research institutes, databases, and trade associations), capital resources and infrastructure (transportation systems, communications systems). In suggesting a hierarchy of factors, Porter distinguishes between basic factors (natural resources, climate, location, unskilled labor and semi-skilled labor) and advanced factors (modern communications infrastructure, educated personnel, and research institutes). He is of the view that advanced factors are the most important for achieving higher order competitive advantage . They are scarce since their development needs sustained investments of both human and physical capital. In discussing the importance of factor creation, Porter opines:

Nations succeed in industries where they are particularly good at creating, and most importantly, upgrading the needed factors. Thus, the nations will be competitive where they possess unusually high quality institutional mechanisms for specialized factor creation. (Porter 1990, p. 80)

3.2 Demand Conditions

Another important component of the model, namely, home demand conditions, shapes the rate and character of improvement and innovation by firms. Porter suggests that there are three broad attributes of home demand: nature of buyer needs of home demand, the size and patterns of growth of home demand (rate of growth of home demand, the presence of independent buyers and early home demand) and the mechanisms by which a nation’s domestic preferences are transmitted to foreign markets through multinational local buyers (Porter 1990, p. 86). Nations can gain advantage when home buyers exert pressure on local firms to innovate faster and achieve more sophisticated advantages. In explaining the nature of buyer needs, Porter suggests that when domestic buyers are sophisticated and demanding and the needs of home buyers anticipate those of other nations, a nation’s firms gain competitive advantage . In support of this view, Moon et al. (1998) hypothesize that a higher level of education among consumers, inter alia, could also increase demand sophistication.

3.3 Related and Supporting Industries

Home-based suppliers and related industries are another attribute of the diamond. The presence of internationally competitive supplier industries creates advantage for downstream industries by providing efficient, early and rapid access to cost-effective inputs and fostering the process of innovation and upgrading (Porter 1990). According to Moon et al. (1998), related and supporting industries are “those whereby firms coordinate or share activities in the value chain or those which involve products that are complementary to the firms of a given nation” (p. 143). The internationally successful related industries provide opportunities for information flow and technical interchange, share activities and forge alliances (Porter 1990).

3.4 Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry

Explaining another broad determinant of national competitive advantage , Porter suggests that the context in which firms are created, organized and managed and the nature of domestic rivalry play a significant role. Firms will succeed when the management practices are favored by the national environment. Also, Porter proposes that some important aspects such as attitudes towards authority, interpersonal interactions, social norms of individualistic or group behavior and professional standards influence the way in which firms are organized and managed. Porter suggests that these grow out of the education system, social of religious history, family structure and many other unique conditions of a nation. The nature of corporate governance and motivations of owners or managers who manage the firms can enhance the success of certain industries when these goals and motivations are aligned with the sources of competitive advantage. Porter expresses a strong preference for vigorous domestic rivalry for creating and sustaining competitive advantage (p. 117). In contrast to the popular argument of wasteful domestic competition, Porter is of the view that nurturing “national champions” can enhance national competitive advantage. He prefers domestic rivalry when improvements and innovations are recognized as the essential ingredients of competitive advantage. Domestic rivalry can take many forms such as price or even technology. Rivalry creates pressure on others to improve, signals others that advancements are possible, attracts new rivals to an industry and fosters government support. Sometimes, domestic rivalry by going beyond economic rationales can become emotional and even personal.

In explaining the exogenous parameters, Porter suggests that chance events, the occurrences that have little to do with the circumstances of a nation, and hence are outside the powers of firms and government, by influencing and being influenced by each of the four determinants, are also significant for determining national competitive advantage .

Despite its wide acceptability, the model is not without its critics. Moon et al. (1998) are of the view that Porter fails to incorporate the effects of multinational activities in the model and this has limited its predictive power (Grant 1991). Hence, a Double Diamond Theory (Rugman and D’Cruz 1993) has been suggested incorporating both domestic and foreign diamonds. Moreover, Moon et al. (1998) have also suggested a generalized Double Diamond Model to analyze small economies.

The next section of this chapter explains how the attributes of Porter’s (1990) Diamond Theory can be used to explain the country readiness of Sri Lanka in adopting IR.

4 Application of Diamond Theory to Sri Lanka

This section illustrates how Sri Lanka displays a high level of readiness for IR adoption by using the four attributes, namely, (a) factor conditions, (b) demand conditions, (c) related and supporting industries, and (d) firm strategy, structure, and rivalry of Porter’s (1990) Diamond Theory.

4.1 Factor Conditions

Sri Lanka is home to many advanced factors that could favorably impact the fast adoption of IR. Among them, its skilled labor force, which is a result of the country’s significant investment in education from 1947, plays a major role (Ministry of Education, MOE 2013). Sri Lanka introduced free education from kindergarten to university in early 1947 (MOE 2013) and this has enabled it to maintain a very high primary and secondary education enrolment ratio (refer Table 3.2).

Due to these investments in human capital, the country enjoyed a literacy rate of 92.5% in 2013 (Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka 2013), which is one of the highest in Asia. Moreover, the country produces approximately 29,000 graduates (both graduate and postgraduate) annually (University Grants Commission, UGC 2013) through its university system. In addition, there are many vocational training colleges, technological institutions, private universities, etc. that offer both graduate and postgraduate level qualifications. While some of these courses focus on accounting and business management that are related to IR directly, others are from different disciplines. These figures, compared with the country’s population of twenty million, become significant in facilitating the adoption of IR. As outlined in the Six Capital Model (refer Sect. 3.2), this diverse knowledge of functional areas facilitates integrated thinking and creating integrated business models within organizations. Since sustainability (or even accounting), in general, can be supported and/or practised by accountants as well as non-accountants (Bennett et al. 2013; Gunarathne et al. 2015; Montano et al. 2001; Schaltegger and Zvezdov 2015), this diverse skill base of the country provides a generally favorable condition for the adoption of IR.

In addition to this general skill base, Sri Lanka is home to three local PABs and two international PABs of UK origin (World Bank 2015). Sri Lanka’s strong accounting profession has its roots dating back to British colonial rule in the country (Senaratne and Cooray 2012). Due to the long presence of the two UK- based accounting bodies, now the country boasts the highest UK-qualified accountants among countries outside the UK (SLASSCOM 2015). Table 3.3 shows the number of students and members of these PABs. Even though the PABs in Sri Lanka date back to British colonial times, the richness of its accounting practices can be traced back to the time of its ancient kingdoms (Liyanarachchi 2009, 2015). Liyanarachchi (2009) provides evidence of the accounting and auditing practices that prevailed in ancient Sri Lanka (from 815 to 1017 AD) showing how accounting was relied upon to maintain the reputation of a Buddhist monastery and that of its members, and thereby maintain goodwill among Buddhist monks, rulers, and people. Liyanarachchi (2015), which is an extension to Liyanarachchi (2009), shows that Buddhist Temple Accounting (BTA) emerged to address the societal need for accountability during that era reflecting the socio-economic needs that motivated them. Hence, concepts such as accounting and accountability have been deeply rooted in Sri Lankan society for a long period, providing a conducive background for the PABs to flourish during and after colonization.

In addition, there are 13 universities and several vocational training colleges that offer degrees and diplomas in accounting specialization (UGC 2013). Additionally, the students of engineering, physical sciences and agriculture also learn accounting and/or business management as part of their degree programs. This skill base, either specializing in accounting or being familiar with accounting/business management, provides an encouraging climate for adopting IR. This is evident in the fact that about 50% of students who earn higher education degrees are trained in technical and business disciplines (AT Kearney 2012). The density of qualified accountants in the country has enabled Sri Lanka to be considered a vibrant business process outsourcing sector for financing and accounting outsourcing (FAO) (World Bank 2015) and to be ranked among the top 19 global centers of excellence for FAO (SLASSCOM 2015).

There have been remarkable infrastructural developments in Sri Lanka recently, particularly in information technology. Colombo, the commercial capital of the country, has been ranked among the top 20 outsourcing destinations in the Asia Pacific region (Tholons 2014). Moreover, AT Kearney (2012) recognized Sri Lanka as a hidden gem for IT, business process outsourcing and knowledge services outsourcing. Compared to other developing nations, the country has a high level of IT literacy as well. In addition to this high level of general IT literacy, the country places a high level of emphasis on the IT skill development of accountants by making it an integral component of the curriculum. Given below are some notable steps taken in this regard:

-

The Department of Accounting (DA) of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura (USJ)Footnote 5 has focused on the development of IT skills among its graduates from the inception (i.e. from 1992); this emphasis is still sustained in its curriculum).

-

The two local PABs, CASL and CMA, offer IT-based accounting course units during and after the professional course.

-

CIMA has now converted its entire examination system into a computer-based system.

In addition to the high level of IT skills, the level of English is high in the country and is considered the language of the business community . Due to the impact of colonial rule from 1815 to 1948, (AT Kearney 2012; Jayewardene 2000), the country has placed a lot of emphasis on learning the English language from kindergarten to university level. The emphasis on English language skill development is also essential for accountants. For instance,

-

The medium of instruction is English in many of the academic accountancy degree programs such as USJ and University of Colombo.

-

In CASL and, CMA only the first two stages are not conducted in English while ACCA and CIMA courses are conducted totally in English.

-

CASL and CMA have separate English language skill development course units.

-

DA of USJ, CASL and CMA have oral practical requirements in the English medium.

The high level of IT use and fluency in English also provide a very positive environment for the accountants to adopt IR easily by means of, but not limited to,

-

Enabling them to easily access international resources including new developments on IR and practices of internationally pioneering companies using the internet.

-

Enabling them to better understand the contents of IR and also to collaborate with foreign parties which could further strengthen its adoption.

-

Supporting them to easily capture sophisticated Information Systems required for the adoption of IR.

-

Enabling them to utilize the available systems and processes in organizations to facilitate models that support IR.

4.2 Demand Conditions

The buyers of IR are a wide set of stakeholders who will use the report for various purposes. There is a great need in Sri Lanka for corporate reporting that focuses not only on financial but also on non-financial performance. This demand stems from various stakeholders including business partners, government, customers, and even society at large.

Sri Lankan society is generally vigilant about the environmental and social implications of business activities. In recent years, ignorance of environmental and social ramifications, corruption, cronyism, nepotism and malpractices have been extensively criticized in the political and social arenas in Sri Lanka. This phenomenon was powerful enough to overthrow the former government of Sri Lanka at the 2015 election (Bandarage 2015). Thus, civil society continuously expects the government as well as organizations to act in an environmentally and socially friendly manner. There are many instances where failure to maintain the social license (Deegan 2000, 2002; Patten 1992), particularly due to ignorance of the impact of organizational activities on the environment and community , have led to a suspension of business activities or social chaos (Cho 2009). For example, water contamination issues such as in RathupaswelaFootnote 6 created significant social unrest in civil society. Due to very high penetration levels of IT, civil society in Sri Lanka is very active in using the electronic media in general and social media in particular for a variety of purposes (Gunawardene 2015). For instance, any malpractice of the government, a corporation or a public institute is immediately published in the social media thus demonstrating the empowerment of the people in developing nations (Ali 2011). This creates pressure on companies to cautiously monitor their activities and performance and also report on them targeting the wider society in a bid to maintain or enhance its social license to operate.

Apart from these pressures, local and foreign buyers of products of Sri Lankan companies also demand better social and environmental performance together with good governance. Since the country has been following an export-oriented policy from 1978, it has become a preferred supplier of apparel, IT solutions, tea, etc. Hence, these organizations, which are mainly export-oriented, are compelled to follow integrated business practices and report on their performance (Fernando et al. 2015; Dissanayake et al. 2016) as part of a global supply chain.

4.3 Related and Supported Industries

From a related and supportive industry perspective, the availability of three local PABs and two foreign PABs bodies (refer Table 3.3) is another favorable condition. These PABs contribute to the adoption of IR in different ways as follows:

-

Since these PABs are IFAC member bodies, they need to align their curricula and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) programs with the International Education Standards (IESs) of IFAC (IFAC 2014). This ensures that the members of these PABs are kept updated on the latest developments in the field of accounting (World Bank 2015).

-

In order to remain relevant and also to differentiate between each other, these PABs (both local and foreign) that operate in Sri Lanka actively take many initiatives to popularize IR. These activities improve the awareness of members while providing training and guidance in IR which provides a favorable environment for adopting IR. Some of these notable activities are shown in Table 3.4 below:

-

These PABs also hold competitions/award schemes on IR. They have become very effective in the speedy diffusion of IR in the Sri Lankan context (Gunarathne and Senaratne 2017). They are listed in Table 3.5 below. They promote awareness, identify issues, and provide guidelines and training opportunities. Through a combination of resources, preparers of integrated reports have access to a rich pool of resources to support high quality reports (World Bank 2015).

-

These PABs not only promote IR but also set an example by preparing their annual reports as integrated reports. Almost all the PABs, both foreign and local, have prepared their latest annual reports as integrated reports. This provides guidance, motivation and models for the companies to prepare their integrated reports.

Not only PABs but also some universities in the country are very active in promoting IR and SR (Gunarathne and Alahakoon 2016). Among them, the DA of USJ has taken many initiatives in this regard including the following:

-

Introduction of IR into the degree curricula.

IR has now been included in the curricula of the following course units in bachelor’s and master’s levels:

-

ACC 3320: Financial Reporting

-

ACC 4322: Advanced Accounting Theory

-

ACC 4327: Sustainability Management Accounting

-

MPACC 1301: Contemporary Issues in Financial Reporting

-

-

Guest lectures on IR to share industry experiences.

-

Forums and conferences related to sustainability that also discuss IR, for example,

-

2014 – Forum on Sustainability Management Accounting

-

2015 – EMAN Global Conference

-

2015 – Business Forum on Sustainability held in parallel with the EMAN Global Conference

-

While the first two activities focus on the students, who will be the future accountants, the last activity mainly focuses on the business community , academics and policy makers of the country who directly apply or promote the adoption of IR.

The availability of consulting firms and assurance providers also plays an important role in providing a conducive environment for the adoption of IR. The country has a well developed supportive industry that comprises:

-

Annual report preparing companies;

-

Consulting firms; and

-

Assurance providers.

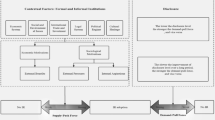

The authors see a nexus between players with related and supportive industry points of view. This nexus is depicted in Fig. 3.2.

The PABs, universities and consulting firms provide the necessary inputs and guidance to the preparers of integrated reports while the annual report preparing companies provide a facilitating role in the integrated report preparation process. The assurance provided by furnishing an external independent view improves the credibility of the information in the reports. In addition to providing inputs for the integrated report preparers, the PABs drive the adoption of IR through their competitions. Hence, the motivating impact of PABs is shown as a dotted line in the nexus.

4.4 Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry

The strategies and structures of Sri Lankan business firms also support the adoption of IR. The preparation of sustainability reports over a long period of time has led many Sri Lankan firms to adopt conducive strategies and structures to support the adoption of IR. As Senaratne et al. (2015) found, there are 105 listed companies that prepare sustainability reports. Also, there are a few other non-listed firms that prepare sustainability reports. As identified by Stubbs and Higgins (2014), the companies that prepare sustainability reports find the adoption of IR to be a transition from sustainability reporting rather than a transformation. This view is further confirmed by Gunarathne and Senaratne (2017) in the Sri Lankan context. By practising sustainability reporting, these companies have built an integrated business model/thinking. For example, these companies have:

-

Separate well established sustainability units/divisions;

-

Persons responsible for sustainability such as sustainability champions whose job descriptions now include the work they have to carry out for sustainability;

-

Availability of information systems that support sustainability information; and

-

Sustainability thinking within the organizations and availability of mechanisms such as 14,000, and ISO 50001.

From a rivalry perspective, as mentioned in the related and supportive industry section, PABs hold many competitions (refer Table 3.6). The situation has therefore promoted competition among the business community to win awards. The number of applications received for the competitions provides evidence of the enthusiasm of the Sri Lankan business community to compete for awards.

Although the four attributes of Porter (1990) can be used to explain why Sri Lanka enjoys a competitive advantage in adopting IR, the authors strongly felt that the explanation is incomplete in this context. Hence, further deliberations and analysis led them to discover a missing attribute in adopting Porter’s Diamond Theory. The next section explains this missing attribute.

5 The Missing Attribute: Impact of National Culture

In the Porter’s Diamond Theory, too little attention has been given to the influence of national culture on the national competitive advantage (Bosch and Prooijen 1992). Bosch and Prooijen (1992) suggest that “the influence of national culture can be shown for every determinant of Porter’s Diamond” and they go on to say “national culture is the base on which the national diamond rests” (p. 176). Echoing a similar view, the authors clearly noticed crucial role the Sri Lankan national culture plays in facilitating IR adoption and its effect on the four attributes of the Diamond Theory. The impact of national culture on accounting practices has been studied extensively and widely debated (Askary 2006; Askary et al. 2008; Gray 1988; Gray and Vint 1995; Lee and Herold 2016; Perera 1989). Many of these studies have referred to Hofstede’s (1980) notable work on national culture. However, so far, we did not come across any study that attempts to integrate national culture to the Diamond Theory to explain the competitive advantage of a nation towards adopting accounting practices.

As outlined briefly in Sect. 3.1, the growing interest in IR in Sri Lanka is a manifestation of concepts such as accountability and sustainability, which are deeply rooted in Sri Lankan society from the time of the ancient kingdoms of the country (from 543 BC to 1815). The maintenance of an irrigation network spreading over the dry zone in the country during the Anuradhapura Kingdom, the first capital of Sri Lanka from 377 BC to 1017, is a classic example of the holistic view adopted in the development of the country by its kings. These irrigation systems consisting of tanks, canals and channels were made to conserve water during the rainy season and use it in paddy cultivation, which was the main livelihood of the people during that time and was remarkably attuned to coping with geological and geographical peculiarities of the location (de Silva 2014). Hence, these irrigation systems contributed to improving the agriculture sector of the economy and social conditions of the people while safeguarding the environment through the conservation of water. This also indicates the broad connotation given to accountability by the Sri Lankan kings focusing on all three dimensions of sustainability – economic, social and environmental. This thinking that has shaped the national culture of the country for many centuries still remains in Sri Lanka.

Though there is no unified national culture (de Silva 2014; Jayawardena 2000), Sinhalese-Buddhist culture is dominant and shared by the majority of Sri Lankans. The central doctrine of Buddha is the concept of “dependent origination” (known as paticca-samuppada), in which the conditionality of all physical and psychical phenomena can be observed (Payutto 1994; Wijeratne 2006). This is in contrast to theism, which advocates the idea of linear thinking and evolution of time and space. Since this way of thinking has been internalized in Sri Lankan society over many centuries, society, including the individuals and social institutions, believes in holistic and system thinking, which is very much akin to the integrated thinking in IR. Thus, the central idea of IR is not alien to Sri Lankan society. In support of our view, Lodhia (2015) shows how the ethical principles valuing the inter-connected nature of economic, environmental and social dimensions of an organization impact on creating integrated thinking on which IR is grounded on. While integrated thinking is a part of the Sri Lankan ethos, there are many other ways in which the Six Capital Model of IR is positively influenced by the concepts in Buddhism. For example, the Buddha’s path to emancipation (vimikka) is laid down in the four Noble (ariya) Truths. The path to emancipation (known as aria attangika-magga or the noble eightfold path), which is the last noble truth, consists of sila (morality), samadhi (mental discipline) and panna (wisdom) (refer Appendix 2). For instance, the sila of the eightfold path is based on compassion and universal love towards all living and non-living beings, which essentially covers the human and natural capitals in the Six Capital Model of IR. The third sila – right livelihood – is to refrain from all ill-virtuous activities and the Sri Lankans regard right livelihood as very important when choosing an occupation or business. This highlights the importance of following governance (mainly self-governance) which is also an essential ingredient of IR. Moreover, Buddha emphasized the importance of investment in the Sigalovada Sutta (of Digha-nikaya), the importance of the environment in the Thera-Theri Gatha (Kuddhika-nikaya), and the duties of a layman towards different stakeholders including employees in the Digha-nikaya (Wijeratne 2006). Though a detailed coverage of Buddhist way of thinking is not expected to be given in this chapter, the authors wish to stress that Buddhist thinking greatly facilitates the integrated thinking and concepts of IR in a number of ways.

However, the authors do not believe that IR will necessarily be an absolute happening in Sri Lanka, mainly due to this cultural aspect. While providing a very favorable condition, Buddhist culture itself leads to a dilemma in regard to the adoption of IR. The Buddhists engage in virtuous and rightful activities as part of their religious observances and do not display an interest in reporting. Perhaps, frequent reporting of such activities, particularly CSR or sustainability, is deemed insincere, not genuine, and this managerial intent overrules the accounting aspect (Fernando 2014). Thus this poses a challenge for managers or corporations. Similarly Buddhists, through their middle path thinking, are self-contained in a mediocre life in which accumulation of material wealth is hardly valued (Nanayakkara 1988). This aspect, the authors think, may reduce the Sri Lankan managers’ or accountants’ desire to achieve excellence in IR. They might possibly settle for an indifferent attitude to IR, and thus may lose interest in keeping abreast of international developments in IR. The duality of the Buddhist culture offers a very conducive environment for the adoption of IR, coupled with the other four factors of national competitive advantage , while restraining the Sri Lankan business community or organizations from achieving great heights in IR. The authors believe that it is the interplay of these two opposing forces of Sri Lankan culture that will decide the future of IR in Sri Lanka .

On the other hand, recent empirical evidence shows that the corporate reporting practices in Sri Lanka are strongly influenced by global reporting guidelines such as GRI (refer Abeydeera et al. 2016b, b for more details). For example, Abeydeera et al. (2016b) find a disconnect between Buddhism as a prevalent institutional force in the local culture and corporate representations evident in SR practices in Sri Lanka particularly owing to later being highly institutionalized by global reporting frameworks such as GRI. Further Abeydeera et al. (2016a) argue that Buddhist values, which that typically shape managers’ private moral positions on sustainability are not generally reflected in the organizations in which they work since the economic factors overshadow the activities of these organizations. Thoradeniya et al. (2015) find that Buddhism significantly affect values and beliefs of managers of Sri Lankan companies particularly of non-listed entities when they engage in SR practices. Though these studies are mainly focused on SR (not necessarily IR), we believe that the national culture alone does not influence the corporations (or managers) to engage in IR or SR practices. Only when these attributes of the Porter’s Diamond Theory are present along with the favourable cultural environment, Sri Lanka is positioned on a strong situation to adopt IR practices than other countries. The recent growth in IR adoption by the corporations in Sri Lanka provides evidence to this.

6 Conclusions

The chapter explained why and how Sri Lanka, an emerging Asia Pacific island nation, displays a high rate of adoption of IR. By drawing on the theoretical framing of Porter’s Diamond Theory, the chapter illustrated how attributes such as the availability of qualified professional accountants and the high level of general education, various stakeholder demands for better ESG reporting, a dynamic accounting profession together with supportive industries, intense competition among organizations and established structures and strategies for SR play a crucial role in facilitating the adoption of new accounting tools such as IR. More importantly, the authors suggest that the national culture , which is very much akin to integrated thinking and Six Capital Model, provides a favourable condition to follow integrated thinking that would eventually lead to IR.

By explaining country readiness of Sri Lanka in adopting IR, the chapter makes several important contributions to the existing body of knowledge of both IR and SR. First, it demonstrates the country context in an emerging Asia Pacific nation in adopting new emerging ESG reporting tools and techniques such as IR (de Villars et al. 2014). Through this, the chapter attempts to broaden the knowledge of IR, which is, so far, based on theoretical investigations and stand-alone case studies (Jensen and Berg 2012) limited mainly to developed countries. Second, the chapter extends Porter’s (1990) Diamond Theory to analyze how a country enjoys competitive advantage in adopting new managerial or accounting technologies. This is a novel approach since the Diamond Theory has been largely used to explain the national competitive advantage of certain industries such as automobile, petrochemical, dairy, music, software, power or education or countries (for instance, see Clancy et al. 2001; Curran 2000; Hodgetts 1993; Sardy and Fetscherin 2009; Sledge 2005; Zhaoa et al. 2011). Third, the paper attempts to integrate the crucial role played by the national culture in promoting or restraining new managerial or accounting tools and techniques in Porter’s Diamond Theory. Although the culture and accounting have been studied extensively in the past, we hardly found any research that investigates the impact of national culture on recently emerging accounting practices such as IR or SR, particularly in the emerging Asian Pacific economies.

Apart from these academic contributions, this chapter deals with some important implications for policy makers and various professions in identifying the requisite conditions for promoting new managerial tools and techniques such as IR and SR. The Diamond Theory essentially provides an analytical framework for governments, regulators, policy makers and professional institutions to identify a situational analysis (such as SWOT). The global accounting players such as IFAC, GRI or IIRC or even other bodies such as the World Bank, UNICEF or UN can understand why some countries report a fast diffusion of new (accounting) concepts or tools while other countries are slow in adopting them. These local or international players thereby can identify the focus areas to concentrate on when promoting new managerial technologies.

Notes

- 1.

Diesel and Motor Engineering PLC (DIMO) is the Sri Lankan company that has taken part in the IIRC Pilot Project. DIMO has a long history dating back to 1939. It has evolved over the years as a corporate entity with a significant presence in the automotive industry and providing services in an array of engineering sectors.

- 2.

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is spread or disseminated through a social system over time (Rogers 1983). As per the temporal trend of diffusion the cumulative adoption path is “S- shaped” with primary, diffusion, condensing and saturation phases. The diffusion stage has a rapidly increasing number of adopters. For more details see Bjørnenak (1997)

- 3.

Managerial technologies are those tools, devices and knowledge that mediate between inputs and outputs (Abrahamson 1991). Since IR combines the inputs, outputs and outcomes of the business models of an organization in terms of various forms of capitals, it falls within the definition of a managerial technology.

- 4.

The formation of IIRC took place in 2010 with the initiation of Prince’s Accounting for Sustainability Project (A4s) and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) . It was initially called the International Integrated Reporting Committee and its name was changed to the International Integrated Reporting Council in 2012.

- 5.

DA, USJ introduced the first accounting degree program in the Sri Lankan University system in 1991.

- 6.

In 2013 the villagers in Rathupaswela had been protesting against a water crisis they faced for a long period. They were demanding that the Rubber Gloves Factory in the area be shut down claiming that the factory waste was polluting the groundwater in the area. When the army was deployed to disperse the protesters, 3 people (including 2 schoolboys) were killed and 36 civilians were injured. This spurred a wide social and political crisis in the country, making the government of that time highly unpopular. Due to the widespread social unrest, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) conducted an investigation and held the army responsible for the shooting (Maduwage 2015).

References

Abeydeera S, Kearins K, Tregidga H (2016a) Does Buddhism enable a different sustainability ethic at work? J Corp Citizenship 6:109–130

Abeydeera S, Tregidga H, Kearins K (2016b) Sustainability reporting – more global than local? Meditari Acc Res 24(4):478–504

Abrahamson E (1991) Managerial fads and fashions: the diffusion and rejection of innovations. Acad Manag Rev 16(3):586–612

ACCA and Net Balance Foundation (2011) Adoption of integrated reporting by the ASX 50. Available via: http://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/acca/global/PDF-technical/sustainability-reporting/tech-tp-air2.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2014

Ali AH (2011) The power of social media in developing nations: new tools for closing the global digital divide and beyond. Harvard Hum Rights J 24:185–219

Askary S (2006) Accounting professionalism – a cultural perspective of developing countries. Manag Audit J 21(1/2):102–111

Askary S, Yazdifar H, Askarany D (2008) Culture and accounting practices in Turkey. Int J Account Audit Perform Eval 5(1):66–88

AT Kearney (2012) Competitive benchmarking: Sri Lanka knowledge services. AT Kearney, Korea

Bandarage A (2015) Good governance in Sri Lanka. The world post. Available via: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/asoka-bandarage/good-governance-in-sri-lanka_b_7087768.html. Accessed 22 Nov 2015

Baron R (2014) The evolution of corporate reporting for integrated performance- background paper for the 30th round table on sustainable development. OECD, Paris

Bellak CJ, Weiss A (1993) A note on the Austrian “diamond”. Manag Int Rev 33(2):109–118

Bennett M, Schaltegger S, Zvezdov D (2013) Exploring corporate practices in management accounting for sustainability. Institute for Chartered Accountants of England and Wales, London

Bjørnenak T (1997) Diffusion and accounting: the case of ABC in Norway. Manag Account Res 8(1):3–17

Bosch FAJ, Prooijen A (1992) The competitive advantage of European nations: the impact of national culture – a missing element in Porter’s analysis? Eur Manag J 10(2):173–177

Brown J, Dillard J (2014) Integrated reporting: on the need for broadening out and opening up. Account Audit Account J 27(7):1120–1156

Cartwright WR (1993) Multiple linked diamonds and the international competitiveness of export-dependent industries: the New Zealand experience. Manag Int Rev 33(2):55–70

Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) (2014) Annual Report. CBSL, Colombo

Cho CH (2009) Legitimation strategies used in response to environmental disaster: a French case study of total SA’s Erika and AZF incidents. Eur Account Rev 18(1):33–62

Clancy P, O’Malley E, O’Connell L, Egeraat CV (2001) Industry clusters in Ireland: an application of Porter’s model of national competitive advantage to three sectors. Eur Plan Stud 9(1):7–28

Curran P (2000) Competition in UK higher education: competitive advantage in the research assessment exercise and Porter’s diamond model. High Educ Q 54:386–410

De Silva KM (2014) A history of Sri Lanka. Vijitha Yapa, Colombo

De Villiers C, Rinaldi L, Unerman J (2014) Integrated reporting: insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Account Audit Account J 27(7):1042–1067

Deegan C (2000) Financial accounting theory. McGraw Hill, Sydney

Deegan C (2002) The legitimizing effect of social and environmental disclosures: a theoretical foundation. Account Audit Account J 15(3):282–311

Deloitte (2012) Integrated reporting, navigating your way to a truly integrated report. 2nd ed. Available via: www.itweb.co.za. Accessed 23 Jan 2015

Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka (2013) Sri Lanka labour force survey annual report – 2013. Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka

Dissanayake D, Tilt C, Xydias-Lobo M (2016) Sustainability reporting by public listed companies in Sri Lanka. J Clean Prod 129:169–182

Eccles RG, Armbrester K (2011) Two disruptive ideas combined: integrated reporting in the cloud. IESE Insight 8(First Quarter–2011):13–20

Eccles RG, Krzus MP (2010) One report: integrated reporting for a sustainable strategy. Wiley, Hoboken

Eccles RG, Saltzman D (2011) Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting. Stanf Soc Innov Rev. Summer–2011:56–61

Eccles RG, Serafeim G (2011) Accelerating the adoption of integrated reporting. de Leo F, Vollbracht M CSR index 2011, Innovation Publishing, Zurich, 70–92

Fernando S (2014) Global and local influences on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) performance and disclosures; evidence from Sri Lankan corporate sector. Keynote address at the Faculty of Management Studies and Commerce (FMSC) Research Session, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka, 5–27 Second Semester – 2014

Fernando S, Lawrence S, Kelly M, Arunachalam M (2015) CSR practices in Sri Lanka: an exploratory analysis. Soc Responsib J 11(4):868–892

Grant RM (1991) Porter’s competitive advantage of nations: an assessment. Strateg Manag J 12(7):535–548

Gray SJ (1988) Towards a theory of cultural influence on the development of accounting systems internationally. Abacus 24(1):1–15

Gray SJ, Vint HM (1995) The impact of culture on accounting disclosures: some international evidence. Asia Pac J Acc 2(1):33–43

Gray R, Javard M, Power DM, Sinclair DC (2001) Social and environmental disclosure and corporate characteristics: a research note and extension. J Bus Finance Acc 28:327–356

Gunarathne N, Senaratne S (2017) Diffusion of integrated reporting in an emerging South Asian (SAARC) nation. Manag Audit J 32(4/5):524–548

Gunarathne N, Peiris S, Edirisooriya K, Jayasinghe R (2015) Environmental management accounting in Sri Lankan enterprises. Department of Accounting, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Nugegoda

Gunawardene N (2015) Social media and general elections 2015. Daily mirror. Available via: http://www.dailymirror.lk/85811/social-media-and-general-elecations-2015. Accessed 23 Nov 2015

Gunarathne ADN, Alahakoon Y (2016) Environmental management accounting practices and their diffusion: the Sri Lankan experience. NSBM J Manag 2(1):1–26

Higgins C, Stubbs W, Love T (2014) Walking the talk(s): organisational narratives of integrated reporting. Account Audit Account J 27(7):1090–1119

Hodgetts RM (1993) Porter’s diamond framework in a Mexican context. Manag Int Rev 33(2):41–54

Hofstede G (1980) Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

IIRC (2013) The international <IR> framework. Available via: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf. Accessed 10 Sept 2014

IIRC (2014) Pilot programme investor network. IIRC. Available via: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/IIRC-Pilot-Programme-Investor-Network-backgrounder-March-2014.pdf. Accessed 23 Dec 2014

International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) (2014) Handbook of international education pronouncements. International Accounting Education Standards Board, IFAC, New York

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2011) Towards integrated reporting, communicating value in the 21st century. IIRC, New York

IoDSA and King III (2009) King code of governance for South Africa 2009. Institute of Directors in Southern Africa and the King Committee on Governance. Available via: http://african.ipapercms.dk/IOD/KINGIII/kingiiireport/. Accessed 23 Feb 2014

Jayawardane VK (2000) Nobodies to somebodies: the rise of the colonial bourgeoisie in Sri Lanka. Social Scientist Association and Sanjiva Books, Colombo

Jensen JC, Berg N (2012) Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting, an institutionalist approach. Bus Strateg Environ 21:299–316

Jensen M, Meckling W (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behaviour agency cost and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360

Kolk A, Van Tulder R (2010) International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. Int Bus Rev 19(2):119–125

KPMG (2008) International survey of corporate responsibility reporting. Available via: https://www.kpmg.com/EU/en/Documents/KPMG_International_survey_Corporate_responsibility_Survey_Reporting_2008.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2014

KPMG (2015) Survey of integrated reports in Japan 2014. Available via: https://www.kpmg.com/jp/ja/knowledge/article/integrated-reporting-article/documents/integrated-reporting-20150628e.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2015

Lee K-H, Herold DM (2016) Cultural relevance in corporate sustainability management: a comparison between Korea and Japan. Asian J Sustain Soc Responsib:1–21

Liyanarachchi GA (2009) Accounting in ancient Sri Lanka: some evidence of the accounting and auditing practices of Buddhist monasteries during 815–1017 AD. Account Hist 14(1–2):101–120

Liyanarachchi GA (2015) Antecedents of double-entry bookkeeping and Buddhist temple accounting. Account Hist 20(1):85–106

Lodhia S (2015) Exploring the transition to integrated reporting through a practice lens: an Australian customer owned bank perspective. J Bus Ethics 129:585–598

Maduwage S (2015) Water woes of Rathupaswala still continue. Daily mirror. Available via: http://www.dailymirror.lk/83401/water-woes-of-rathupaswala-still-continue. Accessed 10 Dec 2015

Ministry of Education (MOE) (2013) Education first – Sri Lanka. Policy and Planning Branch, Ministry of Education, Sri Lanka

Montano JLA, Donoso JA, Hassall T, Joyce J (2001) Vocational skills in the accounting professional profile: the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) employers’ opinion. Acc Educ 10(3):299–313

Moon HC, Rugman AM, Verbeke A (1998) A generalized double diamond approach to the global competitiveness of Korea and Singapore. Int Bus Rev 7:135–150

Nanayakkara G (1988) Culture and management in Sri Lanka. Postgraduate Institute of Management, Sri Lanka

Narada (2010) The Buddha and his teaching, 3rd edn. Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy

Owen D (2006) Emerging issues in sustainability reporting. Bus Strateg Environ 15:217–218

Patten DM (1992) Intra-industry environmental disclosures in response to the Alaskan oil spill: a note on legitimacy theory. Acc Organ Soc 17(5):471–475

Payutto PA (1994) Dependent origination- Buddhist way of conditionality. Buddhamma Foundation, Thailand

Perera MHB (1989) Towards a framework to analyse the impact of culture on accounting. Int J Account 4(1):42–56

Porter ME (1990) The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press, New York

Post JE, Preston LE, Sachs S (2002) Redefining the corporation- stakeholder management and organizational wealth. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Rogers EM (1983) The diffusion of innovations, 3rd edn. Free Press, New York

Rugman AM, Cruz JRD (1993) The “double diamond” model of international competitiveness: the Canadian experience. Manag Int Rev 33(2):17–39

Sardy M, Fetscherin M (2009) A double diamond comparison of the automotive industry of China, India, and South Korea. Compet Forum 7(1):6–16

Schaltegger S, Zvezdov D (2015) Gatekeepers of sustainability information: exploring the roles of accountants. J Account Organ Chang 11(3):333–361

Senaratne S, Cooray S (2012) Dominance of professional accounting bodies and dependence of universities: the case of accounting education in Sri Lanka. In: Proceedings of the accounting and finance Australian and New Zealand AFAANZ annual conference-2012, Melbourne, no pagination July 2012

Senaratne S, Gunarathne N (2017) Excellence perspective for management education from a global accountants’ hub in Asia. In: Baporikar N (ed) Management education for global leadership. IGI Global, Hershey, pp 158–180

Senaratne S, Gunarathne ADN, Herath R, Bandara C (2015) Diffusion of integrated reporting in an emerging economy. In: Proceedings of the Environmental and Sustainability Management Accounting Network (EMAN) global conference – 2015. University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Colombo, 120–137, January 2015

Seuring S, Muller M (2008) From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J Clean Prod 16(15):1699–1710

Simnett R, Huggins AL (2015) Integrated reporting and assurance: where can research add value? Sustain Acc Manag Policy J 6(1):29–53

Sison AJG (2010) Corporate governance and ethics: an Aristotelian perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

SLASSCOM (2015) Sri Lankan IT/BPM industry 2014 review. SLASSCOM, Colombo

Sledge S (2005) Does Porter’s diamond hold in the global automotive industry? Adv Compet Res – ACR 13(1):22–32

Stent W, Dowler T (2015) Early assessments of the gap between integrated reporting and current corporate reporting. Meditari Acc Res 23(1):92–117

Stubbs W, Higgins C (2014) Integrated reporting and internal mechanisms of change. Account Audit Account J 27(7):1068–1090

Tholons (2014) 2014 – tholons top 100 outsourcing destinations: regional overview. Available via: http://www.tholons.com/nl_pdf/Whitepaper_December_2013.pdf. Accessed 01 Dec 2015

Thoradeniya P, Lee J, Tan R, Ferreira A (2015) Sustainability reporting and the theory of planned behaviour. Account Audit Account J 28(7):1099–1137

University Grants Commission (UGC) (2013) Thirty fourth annual report- 2012. UGC, Sri Lanka

Van Staden C, Wild S (2013) Integrated reporting: an initial analysis of early reporters. In: Proceedings of the Massey University Accounting Research Seminar. Massey University, Auckland

Weeramantry CG (2002) Sustainable development: an ancient concept recently revived. Global judges symposium on sustainable development and the role of law. Johannesburg, South Africa, Available via: http://www.unep.org/delc/Portals/119/publications/Speeches/Weeramantry.pdf. Accessed 08 Dec 2015

Wijeratne AT (2006) A Buddhist’s view on sustainability – a heretic’s thoughts on the economy. Agra T. Wijeratne, Pannipitiya

World Bank (2015) Report on the observance of standards and codes, accounting and auditing – Sri Lanka. World Bank, Washington, DC

Zhaoa Z, Zhanga S, Zuo J (2011) A critical analysis of the photovoltaic power industry in China – from diamond model to gear model. Renew Sust Energ Rev 15(9):4963–4971

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix 1: Linking sustainability performance to six capitals

* Intellectual capital (i.e. organizational knowledge-based intangibles, including intellectual property and organizational capital) can be mainly related to economic and social performance. It should also be noted the relationships given above are not mutually exclusive and hence there can be many other linkages among sustainability performance aspects to six capitals

1.2 Appendix 2: Eightfold path of Buddha’s way of emancipation

Division | Eightfold-path factors |

|---|---|

Wisdom (panna) | 1. Right view/understanding (Samma-Ditthi) |

2. Right intention (Samma-Sankappa) | |

Ethical conduct/morality (sila) | 3. Right speech (Samma-Vaca) |

4. Right action (Samma-Kammanta) | |

5. Right livelihood (Samma-Ajiva) | |

Concentration/mental discipline (samadhi) | 6. Right effort (Samma-Vayama) |

7. Right mindfulness (Samma-Sati) | |

8. Right concentration (Samma-Samadhi) |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gunarathne, A.D.N., Senaratne, S. (2018). Country Readiness in Adopting Integrated Reporting: A Diamond Theory Approach from an Asian Pacific Economy. In: Lee, KH., Schaltegger, S. (eds) Accounting for Sustainability: Asia Pacific Perspectives. Eco-Efficiency in Industry and Science, vol 33. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70899-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70899-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-70898-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-70899-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)