Abstract

In this contribution, we analyse the effects of financialisation on income distribution, before and after the Great Financial Crisis and the Great Recession. The analysis is based on a Kaleckian theory of income distribution adapted to the conditions of financialisation. Financialisation may affect aggregate wage or gross profit shares of the economy as a whole through three channels: first, the sectoral composition of the economy; second, the financial overhead costs and profit claims of the rentiers; and, third, the bargaining power of workers and trade unions. We examine empirical indicators for each of these channels for six OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) economies, both before and after the crisis. We find that these countries have shown broad similarities regarding redistribution before the crisis, however, with differences in the underlying determinants. These differences have carried through to the period after the crisis and have led to different results regarding the development of distribution since then.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Code

1 Introduction

The effects of financialisation , or of the “increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies” to use Epstein’s (2005, p. 3) widely quoted definition, on income distribution have been explored in several contributions, as recently reviewed by Hein (2015). Redistribution of income has taken place at different levels, from labour to capital, from workers to top managers and from low-income households, mainly drawing on wage incomes, to the rich, drawing on distributed profits (dividends, interest, rents) and top management salaries . This has contributed to severe macroeconomic imbalances at both national and international levels, i.e. rising and unsustainable household debt -to-income ratios in some countries and severe current account imbalances at regional (Euro area) and global levels, which then led to the severity of the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9, starting in the USA and spreading over the globe (Hein 2012; Stockhammer 2010, 2012, 2015a).

The recovery from the crisis has been rather sluggish so far, and this has given rise to a renewed discussion about stagnation tendencies in mature capitalist economies. In the mainstream version of this debate, as represented by Summers’s (2014, 2015) ‘secular stagnation ’ hypothesis, distributional issues are ignored or they play only a marginal role at best. Post-Keynesian approaches, however, focus on income distribution , as well as on the stance of macroeconomic policy, when it comes to explaining stagnation tendencies after the crisis (Blecker 2016; Cynnamon and Fazzari 2015, 2016; Hein 2016; Palley 2016; van Treeck 2015). Therefore, in this contribution, we will try to shed some light on the development of income distribution before and since the outbreak of the crisis for a set of mature capitalist economies, and on the role financialisation has played in all this. The main focus will be on functional income distribution (wage and profit shares ), but we will also look at indicators for personal or household distribution of income (Gini coefficients , top income shares).

Of course, we are not the first to study the distributional consequences and effects of the crisis, as, for example, the papers by Cynnamon and Fazzari (2016) and Dufour and Orhangazi (2015) on the USA , by Branston et al. (2014) on the USA and the UK , or by Schneider et al. (2016) on the Eurozone testify. However, we will provide the results of a comparative analysis for six developed OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries applying a consistent Kaleckian approach for the examination of the effects of financialisation on functional income shares, with a respective unique set of indicators, as proposed by Hein (2015), and initially applied by Hein and Detzer (2015) for the case of Germany . The countries included in the current overview comprise three main ‘debt -led private demand boom’ economies before the crisis, the USA, the UK and Spain , which had managed to over-compensate the lack of investment and income-financed consumption demand by credit-financed consumption before the crisis. According to Dodig et al. (2016), in the course and after the crisis, the UK and the USA turned towards domestic demand-led economies mainly relying on government deficits to stabilise demand, whereas Spain under the dominance of the Euro area regime and the imposed austerity policies turned towards an export-led mercantilist economy drawing on improved net exports as a driver of meagre demand growth . Next we have two main ‘export-led mercantilist’ economies before the crisis, Germany and Sweden , which had (partly) compensated the lack of investment and income-financed consumption demand by rising net exports and current account surpluses before the crisis. In the course and after the crisis, these countries have seen an increasing relevance of domestic demand, however, with persistently high current account surpluses, which still qualify them as ‘export led’, according to Dodig et al. (2016). And, finally, we have France as a ‘domestic-demand-led’ economy before the crisis, which has remained so in the course and after the crisis, according to Dodig et al. (2016). In this contribution, we will be able to present only the overall pattern of results for the relationship between financialisation and income distribution before and after the crisis derived from detailed data analysis for the respective countries. The presentation of the data for each of the countries we have studied in order to generate this pattern can be found in Hein et al. (2017).

Our contribution is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, we will review the trends of distribution before and after the crisis for the six countries we have examined. We will look at the development of the adjusted wage share , top income shares and the Gini coefficients for both market and disposable incomes. Due to data constraints, we will focus on the period from the early/mid-1990s until the financial and economic crisis, and then on the period since the crisis. Sect. 3 will provide the theoretical backbone of our contribution, a Kaleckian theory of income distribution adapted to the conditions of financialisation . Sect. 4 will contain the results of our country studies. Sect. 5 will provide a comparison, and Sect. 6 will summarise and offer some conclusions regarding the determinants of distributional change before and after the financial and economic crisis.

2 Trends in Redistribution Before and After the Crisis

Looking at the evolution of different indicators for income inequality , it can be said that the era of financialisation was marked by three redistributional trends from the early 1980s until the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9.

First, from the late 1970s/early 1980s until the Great Recession (2008–9), income was redistributed from labour to capital. Figure 1 presents the adjusted wage share as percentage of GDP at factor costs for our countries from 1970 until 2015.Footnote 1 All the countries considered here have seen, apart from cyclical fluctuations, a downward trend at least from the early 1980s until the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9. However, in several countries most of the redistribution took place in the course of the 1980s. Our comparative analysis of the determinants of redistribution in Sect. 4 will be constrained to the period starting in the early 1990s or even later, mainly due to data availability. Therefore, we need to take a closer look at distributional tendencies from the early 1990s until the Great Recession and at the developments since then. Here we find that for the USA , Spain , Germany and to a lesser degree for France and Sweden also, the period from the early 1990s until 2007 was characterised by a tendency of the adjusted wage share to fall. However, in the UK , the adjusted wage share remained roughly constant in this period. After the crisis, a continuation of the downward trend can be observed in the USA and Spain, and also in the UK, the adjusted wage share has shown a falling trend. In Germany and Sweden, the falling trend could be stopped and the adjusted wage share seems to have remained constant, and in France even a slightly upward trend can be observed after the crisis.

Adjusted wage share , selected OECD countries, 1970–2015 (per cent of GDP at factor costs). (Note: The adjusted wage share is defined as compensation per employee as a share of GDP at factor costs per person employed. It thus includes the labour income of both dependent and self-employed workers, and GDP excludes taxes but includes subsidies; Source: European Commission (2016), our presentations)

Figure 2 shows the development of the top 1 per cent income shares for our countries, covering the years 1970 until 2015, if possible.Footnote 2 For the reason mentioned above, let us focus again on the period from the early 1990s until the crisis, on the one hand, and on the period since then, on the other. In the USA and the UK , already starting in the early 1980s, the top income share experienced a remarkable increase until the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9. In the case of the USA, the rise was considerably driven by a rise in top management salaries (Hein 2015). In Spain , Germany , Sweden and France the top 1 per cent income share only started to rise in the 1990s or even the early 2000s, but it increased as well until the crisis of 2007–09, but not to the same level as in the USA or the UK. After the crisis, top income shares started to rise again in the USA, they remained roughly constant in Sweden and France, and they started to decline in the UK and Spain. For Germany, due to a lack of recent data, no statement about the development after the crisis can be made.

Top 1 per cent income share; selected OECD countries, 1970–2015 (per cent of pre-tax fiscal income without capital gains). (Note: For France , Germany , Spain , Sweden and the USA , shares relate to tax units; in the case of the UK , data covering the years 1970 until 1989 comprise married couples and single adults and from 1990 until 2012 adults; Source: The World Wealth and Income Database (2016), our presentation)

Figures 3 and 4 show the development of Gini coefficients for market and disposable income, respectively, covering the years 1970 until 2015, if possible and thus demonstrate developments in personal income distribution . Again we focus on the period from the early 1990s until the crisis and on the period since then. Before the crisis, the Gini coefficient for market income increased significantly in the USA , the UK , Germany and Sweden , while it remained roughly constant in France and Spain , with wide fluctuations in the latter country, however. With the crisis of 2007–09, the rise in the Gini coefficient of market income was especially pronounced in Spain and this upward trend seems to have continued since then. It can also be observed in the USA and Germany, but less so in Sweden. In the UK the Gini coefficient for market income has remained constant on a very high level, and in France it has even declined.

Gini coefficient of market income of selected OECD countries (1970–2015). (Note: The Gini coefficient is based on equivalised (square root scale) household market (pre-tax, pre-transfer) income. Source: Adapted from Solt (2016).)

Gini coefficient of disposable income of selected OECD countries (1970–2015). (Note: The Gini coefficient is based on equivalised (square root scale) household disposable (post-tax, post-transfer) income. Source: Adapted from Solt (2016).)

With regard to the development of the Gini coefficient of disposable income, which measures personal income inequality after taxes and transfer payments, the picture is rather mixed. In France , this Gini coefficient also remained constant until 2009 when it even started to decline. In the UK , this Gini coefficient had increased in the 1980s, and in the 1990s, it remained relatively constant until the crisis, while since then it has shown a slight downward trend. In Spain , the Gini coefficient increased tremendously in the early 1990s and followed a downward trend from the mid-1990s until the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9, when inequality increased again. In Germany , the Gini coefficient of disposable income shows a sustained upward trend, before and after the crisis. The same holds true for the USA , which has had the highest Gini coefficient for disposable income in our data set. In Sweden , the Gini coefficient of disposable income was rising until the crisis but has stabilised since then and has remained at the lowest level in our set.

3 The Effect of Financialisation on Income Distribution: A Kaleckian Approach

In this section, we outline a Kaleckian approach towards the explanation of the development of income shares, i.e. profit and wage share s, under the conditions of financialisation . The focus here is on the determination of functional income distribution because changes in the latter will also affect the personal or household distribution of income.Footnote 3 In other words, if financialisation triggers falling labour income shares and hence rising gross profit shares , including retained profits, dividends, interest and rents, this should also contribute to rising inequality of household incomes. The major reason for this is the unequal distribution of wealth, which generates access to capital income and hence gross profits. If the profit share increases, this will then also increase the inequality of household incomes to the extent that profits are distributed to households according to the unequal distribution of profit-generating wealth. Of course, if rising profits—relative to wages—are retained in the corporate sector and thus not distributed to wealthy households, the link between redistribution at the functional level and at the personal/household level will be weakened.

Hein (2015) has reviewed the recent general empirical literature on the determinants of income shares against the background of the Kaleckian theory of distribution, in order to identify the channels through which financialisation and neo-liberalism have affected functional income distribution . According to the Kaleckian approach (Kalecki 1954, Part I; Hein 2014, Chap. 5), the gross profit share in national income, which includes retained earnings, dividend, interest and rent payments, as well as overhead costs (thus also top management salaries ) can be determined as follows, starting from pricing in incompletely competitive goods and services markets.

With Kalecki we assume that firms mark up marginal costs which are roughly constant up to full-capacity output given by the available capital stock. This implies that the mark-up is applied to constant average variable costs. Unit variable costs are composed of unit direct labour costs and unit material costs. To the extent that raw materials and semi-finished products are imported from abroad, international trade is thus included into the model. In this approach, the mark-up has to cover overhead costs, i.e. depreciation of fixed capital and in particular salaries of overhead labour, on the one hand, and firms’ gross profits, i.e. interest and dividend payments as well as retained profits, on the other hand.

For a domestic industrial or service sector j, which uses fixed capital, labour and imported raw materials and semi-finished goods as inputs, we get the following pricing equation:

with p j denoting the average output price in sector j, m j the average mark-up, w the average nominal wage rate, a j the average labour-output ratio, p f the average unit price of imported material or semi-finished products in foreign currency, e the exchange rate and μ j imported materials or semi-finished inputs per unit of output. Since the relationship between unit material costs and unit labour costs (z j ) is given by

the price equation can also be written as

The gross profit share (h j ), including overhead costs and thus also management salaries , in gross value added of sector j is given by

with Π denoting gross profits, including overhead costs, and W representing wages for direct labour. For the corresponding share of wages for direct labour in gross value added (1− h j ) we obtain

The gross profit share (h), including overhead costs, for the economy as a whole is given by the weighted average of the sectoral profit shares , and the wage share of direct labour (1 − h) for the economy by the weighted average of the sectoral wage shares:

Functional income distribution is thus determined by the mark-up in pricing of firms, by the relationship of unit material costs to unit labour costs and by the sectoral composition of the economy. According to Kalecki (1954, pp. 17–8) the mark-up, or what he calls the ‘degree of monopoly’, has several determinants.

First, the mark-up is positively related to the degree of concentration within the respective industry or sector. Second, the mark-up is negatively related to the relevance of price competition relative to other forms of competition (product differentiation, marketing, etc.). We summarise these two determinants as the ‘degree of price competition among firms in the goods market’. Third, Kalecki claims that the power of trade unions has an adverse effect on the mark-up. In a kind of strategic game, firms anticipate that strong trade unions will demand higher wages if the mark-up and hence profits exceed ‘reasonable’ or ‘conventional’ levels, so that the excessively high mark-up can only be sustained at the expense of ever-rising prices and finally a loss of competiveness of the firm. This will induce firms to constrain the mark-up in the first place. Of course, this will become effective only if there is heterogeneity within the firm sector, such that firms are either facing different increases in nominal wages or they are operating with different technologies, such that the increase in nominal wages will lead to different changes in their unit direct labour costs. Fourth, Kalecki argues that overhead costs may affect the degree of monopoly and hence the mark-up. Since a rise in overhead costs squeezes gross profits, “there may arise a tacit agreement among the firms of an industry to ‘protect’ profits, and consequently to increase prices in relation to unit prime costs” (Kalecki 1954, p. 17).Footnote 4 From the perspective of the firm, interest payments on debt are also part of overhead costs, and thus the idea of an interest rate or interest payments elastic mark-up has been introduced into Kaleckian models of distribution and growth (Hein 2014, Chap. 9). A permanent increase in interest rates (or interest payments) would thus induce firms, on average, to increase the mark-up in order to survive. Recently, this idea has been further extended arguing that from the perspective of the management of the firm, dividend payments are as well a kind of overhead obligations. A permanent increase of dividend payments could therefore induce management to recover this drain of funds for real investment or other purposes by means of increasing the mark-up, either by raising prices or by forcing down unit labour costs if market conditions and the relative bargaining power of firms and labour unions allow for (Hein 2014, Chap. 10).

From this model, we obtain the three determinants of functional income distribution , here the gross profit share, including overheads, and hence management salaries , as shown in Table 1. First, the profit share is affected by firms’ pricing in incompletely competitive goods markets, i.e. by the mark-up on unit variable or direct costs, with the mark-up being determined by the degree of price competition, workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power , and by overhead costs and gross profit targets as explained above. Second, with mark-up pricing on unit variable costs, i.e. material plus wage costs, the profit share in national income is affected by unit (imported) material costs relative to unit wage costs. With a constant mark-up, an increase in unit material costs will thus increase the profit share in national income. And third, the aggregate profit share of the economy as a whole is a weighted average of the industry or sector profit shares . Since profit shares differ among industries and sectors, the aggregate profit share is therefore affected by the industry or sector composition of the economy.

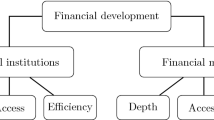

Integrating some stylised facts of financialisation and neo-liberalism into this approach and reviewing the respective international empirical and econometric literature, Hein (2015) has argued that there is some convincing empirical evidence that financialisation and neo-liberalism have contributed to the rising profit share, and hence to the falling labour income share since the early 1980s, through three main channels, as can also be seen in Table 1.Footnote 5

First, the shift in the sector composition of the economy, from the public sector and the non-financial business sector with higher labour income shares towards the financial business sector with a lower labour income share, has contributed to the fall in the labour income share for the economy as a whole in some countries.

Second, the increase in management salaries as a part of overhead costs, together with rising profit claims of the rentiers , i.e. rising interest and dividend payments of the corporate sector, has in sum been associated with a falling labour income share. Since management salaries are part of compensation of employees in the national accounts and thus of the labour income share, or the adjusted wage share as shown in the previous section, the wage share, excluding (top) management salaries, has fallen even more strongly than the wage share taken from the national accounts.

Third, financialisation and neo-liberalism have weakened trade union bargaining power through several channels: increasing shareholder value and short-term profitability orientation of management; sectoral shifts away from the public sector and the non-financial business sector with stronger trade unions in many countries to the financial sector with weaker unions; abandonment of government demand management and full employment policies; deregulation of the labour market; and liberalisation and globalisation of international trade and finance.

Of course, these channels may not apply to all the developed capitalist economies affected by financialisation to the same degree, if at all. In the following section, we will therefore review the results we have obtained for empirical indicators for these channels for our six countries in Hein et al. (2017), and assess the development, before the financial and economic crisis from the early 1990s until 2007–9 and then in the course and after the crisis.

For the first channel, the sectoral composition channel, we have looked at the contributions of the financial corporate, the non-financial corporate, the household and the government sectors to gross value added of the respective economies, and at the profit shares in the financial and non-financial corporate sectors, in particular. This has allowed us to see whether there has been the expected structural change in favour of the financial sector, whether the financial corporate sector has had a higher profit share than the non-financial corporate sector and whether a potential change in the sectoral composition of the economy in favour of the financial corporate sector as such has contributed to a rise in the profit share and hence a fall in the wage share for the economy as a whole.

For the second channel, the financial overhead costs or rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we have more closely examined the functional distribution of national income and distinguished the different components of aggregate profits in order to see whether a rise in the profit share benefitted firms in terms of retained earnings or rather rentiers in terms of distributed profits, dividends and interest, in particular. In turn, this has allowed us to infer whether rising income claims of rentiers—and thus overhead costs of firms—have come at the expense of workers’ income or at the expense of retained earnings under the control of the management of firms.

And, finally, for the third channel, the bargaining power channel, we have assessed several determinants of workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power. A first set has been related to the labour market, and we have looked at unemployment rates, union density, wage bargaining coverage, the strictness of employment protection for different types of workers, and at the gross and net unemployment benefits replacement rates. In this context, we have also considered the development of trade openness in order to assess the pressure of international competition on workers and trade unions, and we have taken a look at households’ debt -to-GDP ratios, which should also negatively affect workers’ and trade unions’ bargaining power, according to Barba and Pivetti (2009). Finally, we have assessed the bargaining power of workers at the non-financial corporate level. This should be affected by the managers’ interest in the maximisation of short-term profits in favour of shareholder value as opposed to the long-term growth of the firm. This strategy implies boosting share prices by paying out profits to shareholders, squeezing workers, and by financial investment s instead of real investments in the capital stock of the firm. In terms of indicators, we have examined the relevance of property income received (interest and dividends) in relation to the operating surplus of non-financial corporations to assess the relevance of real vs. financial investments and property income paid to identify the distributional pressure of shareholders on the management. A high relevance of received financial profits and of dividend payments, in particular, was interpreted as indicating a high shareholder value orientation of management, which should be detrimental to workers’ bargaining power at the corporate level.

4 Results from Country Studies

4.1 The USA

4.1.1 The USA Before the Crisis

As we have shown in Sect. 2, in the decades before the crisis the USA has seen a tendency of the adjusted wage share to fall, which was accompanied by a spectacular rise in top income shares, partly driven by rising top management salaries , as well as by an increase in Gini coefficients both for market income and for disposable income of households. We will focus here on the contribution of financialisation to this development, paying attention to the period from the early 1990s until the crisis and making use of the model outlined in Sect. 3.Footnote 6

Looking at the sectoral composition of gross value added of the US economy and the sectoral profit shares as determinants of aggregate wage and profit shares, we have found that the contribution of non-financial corporations to value added declined before the crisis of 2007–9. The share of the financial corporate sector in gross value added slightly increased, and the same was true for the household sector, including non-corporate business. At the same time, the profitability of the financial sector remained well above that of the non-financial sector. The sectoral composition effect in favour of the financial sector thus contributed to the rise of the aggregate profit share in the USA before the crisis.

In order to examine the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we first looked at the developments of the components of net national income. Having risen considerably in the 1980s (Dünhaupt 2012), the share of net property income, the rentiers’ income share, remained somewhat constant from the 1990s until the financial and economic crisis, and then only rose shortly before the crisis. The share of retained earnings had a slightly rising trend from the 1990s until the crisis, while the labour income share was on a slightly falling trend. Whereas the financial overheads/rentiers’ profit claims channel had a strong effect on redistribution at the expense of the wage share in the 1980s (Dünhaupt 2012), when corporations managed to pass through the rising profit claims of rentiers putting pressure on workers and squeezing their claim on value added, this channel considerably weakened in the 1990s and in the early 2000s but still contributed to the fall of the wage share.

Looking at the components of the rentiers ’ income share, we also found for the period from the early 1990s until the crisis a strong indication for increasing power of shareholders and increasing shareholder value orientation of management. While the share of interest income in net national income in a period of very low interest rate saw a rapid decline, the share of distributed property income, i.e. mainly dividends, rose remarkably in the period before the financial and economic crisis.

Assessing the bargaining power channel of redistribution under the conditions of financialisation and neo-liberalism , we first considered several indicators directly related to the labour market. First, the unemployment rate was quite low in the period before the crisis of 2007–9, although slightly higher than in the boom of the late 1990s. Trade union density in the USA was among the lowest in this multi-country study and further declined in the period before the crisis. The same holds true for wage bargaining coverage, leaving a high and increasing number of workers unprotected by collective labour agreements regarding wages and working conditions. Second, with respect to employment protection , nothing changed in the immediate period before the crisis; the USA remained at very low levels in this regard, too. However, as a counterpart to this labour market deterioration, unemployment benefits improved somewhat over the years before the crisis, but again from very low levels in international comparison. Furthermore, the internationalisation and globalisation of finance and trade put pressure on workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power, as indicated by steadily growing trade openness of the US economy, albeit from a very low level compared to other countries in our dataset. Finally, household debt -to-GDP ratios significantly increased in the early 2000s, constraining workers’ bargaining power in the labour market because increasing relevance of fixed payment commitments, in particular, for mortgages, made potential job and income losses even more severe.

The bargaining power of workers at the firm level is affected by the managers’ tendency to maximise short-term profits in favour of shareholders. Regarding property income received in relation to the operating surplus of non-financial corporations, from the early 1990s until the crisis, there cannot be seen an overall increase in the relevance of distributed property income nor of dividend payments (distributed income of corporations), in particular, in contrast to what had happened in the 1980s (Dünhaupt 2012). Therefore, this indicator does not show a further rise in the relevance of financial investment boosting short-term profits and thus an increase in shareholder value orientation of management. Turning to property income paid in relation to the operating surplus, we see no overall increase, but a rise in the relevance of dividend payments (distributed income of corporations) can be observed, which indicates an increase in shareholder value orientation of non-financial corporate management from the early 1990s until the crisis.

Summing up the US case before the crisis, we have found support for all three channels of transmission of the rising dominance of finance on functional income distribution . The sectoral composition changed in favour of the financial corporate sector with a higher profit share, financial overhead costs and rentiers ’ profit claims increased, and workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power significantly deteriorated.

4.1.2 The USA in the Course and After the Crisis

Since the financial and economic crisis of 2007–9, the tendency of a declining wage share in the USA seems to have been persisting. Similarly, top income shares and the Gini coefficients for market and disposable incomes also seem to have risen after the crisis. Overall inequality has thus increased in the course and after the crisis, as has also been observed by Branston et al. (2014), Cynamon and Fazzari (2016) and Dufour and Orhangazi (2015).

Looking at our channels of redistribution in finance-dominated capitalism, we have found a slight increase in the share of financial corporations in value added, as well as in financial sector profitability relative to the non-financial corporate sector after the respective drops during the crisis. The sectoral composition effect has therefore contributed to the continuous fall of the aggregate wage share after the crisis.

With regard to the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we have observed an increase in the share of net property income in net national income and a corresponding fall in the wage share , and also in the share of retained earnings since 2010. This increase in the share of net property income has been driven by a recovery of the share of dividend income, which had seen a sharp drop during the crisis, but now has reached the high pre-crisis values again. Therefore, also the financial overheads/rentiers’ profit claims channel has contributed to the fall of the wage share and the rise in inequality in the course and after the crisis.

Finally, looking at the indicators for the workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power channel, we have found that the bargaining power of workers seems to have become even weaker after the crisis. Unemployment has increased to levels not seen since the 1990s, and union density and bargaining coverage have further declined. The degree of openness of the US economy and hence international competition has risen and put additional pressure on workers and trade unions. However, employment protection has remained constant, and unemployment benefit replacement rates have even increased. In addition, household debt has decreased due to deleveraging. With regard to shareholder value orientation of management and hence workers’ bargaining power at the non-financial corporate level, both of our indicators have shown a decline in shareholder value orientation: The relevance of property income received in relation to the operating surplus has declined. As for the relevance of the property income paid out, it has remained constant after the fall in the course of the crisis and is now well below the pre-crisis value, with the dividends paid out remaining constant at the pre-crisis level. Overall, our indicators for the bargaining power channel have shown some ambiguous results.

Therefore, the continuous fall in the wage share and rising inequality in the USA since the crisis can be related to a further change in the sectoral composition towards the financial corporate sector with a higher profit share, and a rise in financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims. The improvement of some indicators of workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power at the non-financial corporate level was accompanied by the further deterioration of the economy-wide and labour market determinants.

4.2 The UK

4.2.1 The UK Before the Crisis

For the UK , in Sect. 2, we have seen a constant adjusted wage share from the 1990s until the crisis, which was, however, associated with a considerable rise in top income shares, as well as an increase in Gini coefficients both for market and disposable incomes of households. Again we will focus here on the contribution of financialisation to these developments following the model outlined in Sect. 3.Footnote 7

We first address the sector composition channel for the effect of financialisation on functional income distribution . It could be observed that while the share of the government sector in gross value added of the economy remained roughly constant in the period from the mid-1990s until the crisis, the share of the financial corporate sector increased considerably from 5 per cent in 2000 to over 8.5 per cent in 2007. This was accompanied by a fall in the share of the non-financial corporate sector in the same period from 60.5 per cent in 2000 to 56.7 per cent in 2007. At the same time, the profit share of the financial corporate sector was higher than the profit share of the non-financial corporate sector during the whole pre-crisis period except for 1999–2002. This suggests that the increasing share of the financial sector should have been conducive to an overall rise in the profit share and a fall in the wage share —which we did not observe, however, because the profit shares , both in the financial and in the non-financial corporate sectors, had a slight tendency to fall before the crisis, with wide fluctuations in the profit share of the financial corporate sector.

For the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, there has been no evidence for an increase in the profit claims of rentiers, since the share of rentiers’ income (net property income) in net national income decreased from close to 14 per cent in 2000 to close to 11 per cent in 2007. This downward trend in the share of rentiers’ income as a whole has also been found for the main components, including the share of dividend incomes. This allowed the share of retained earnings to rise considerably, and also the labour income share could recover in the years before the crisis.

For the bargaining power channel, we have found the following results. First, unemployment rates were on a downward trend until the crisis, but the union density rate declined by more than 10 percentage points from the early 1990s until the crisis. Similarly, the bargaining coverage rate fell by almost 10 percentage points. The indicators for employment protection showed little change from the 1990s onwards; the same was true for unemployment benefit replacement rates. The increasing degree of trade openness and rising household debt ratios, however, should have weakened workers’ bargaining power.

Finally, looking at the shareholder value orientation of management, and hence at property income received and paid by non-financial corporations, we have found some indications for a shift of managers’ preferences in favour of financial investment s over real investment in the capital stock, which should have been detrimental to the bargaining power of workers at the non-financial corporate level. Between the mid-1990s and 2007, the relevance of total property income relative to the operating surplus of non-financial corporations increased substantially, driven primarily by dividends received. However, for the UK we do not find an increase in the relevance of profits of non-financial corporations being distributed as dividend payments (distributed income of corporations). Overall, some indicators have shown a weakening of trade union bargaining power, which should have contributed to a fall in the wage share , whereas others have not.

Summing up the UK case before the crisis, we have obtained ambiguous findings regarding the change in the sectoral composition towards the financial corporate sector and the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, as well as with respect to workers’ and trade union’s bargaining power . This might explain why the aggregate wage share in the UK remained roughly constant in the period before the crisis, whereas the other distributional indicators have shown rising inequality .

4.2.2 The UK in the Course of and After the Crisis

Since the crisis the adjusted wage share in the UK has seen a tendency to fall, whereas top income shares have been somewhat reduced and Gini coefficients have remained constant at high levels. Since the Great Recession , a few indicators have pointed to the weakening of the importance of finance in the UK economy. First, the share of financial corporations in gross value added has somewhat declined, whereas the share of non-financial corporations has recovered. The profit share of the financial corporate sector has remained stable and is still higher than the profit share of the non-financial corporate sector. Taken together, this means that the sectoral composition channel has rather provided the conditions for a recovery of the wage share and also for a decline in household income inequality .

With regard to the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we have found a slight tendency of the rentiers’ income share to decline after the crisis, which should also have been conducive to a rise in the wage share .

Regarding the third channel, however, the workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power channel, a considerable weakening of the workers’ position could be observed starting with the crisis. Unemployment has been significantly higher than in the period before the crisis, and trade union membership and bargaining coverage has further declined. The indicators for employment protection have remained roughly constant, as have the unemployment benefit replacement rates. Household indebtedness has remained at a very high level, and trade openness has increased further, putting additional pressure on workers’ bargaining power.

Furthermore, since the Great Recession , the relevance of financial investment as compared to real investment of non-financial corporations seems to have slightly increased. Although the importance of total property income received by non-financial corporations has declined, driven primarily by falling interest income, the relevance of dividend payments obtained has increased considerably. Finally, since 2008 the distributed income of corporations, i.e. dividend payments, in relation to the operating surplus of non-financial corporation has increased. Each development indicates a rising orientation of managers towards shareholder value, which comes at the expense of the power of other stakeholders in the corporation, i.e. labour.

In sum, whereas the sectoral composition and the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channels of financialisation would have allowed for a rise in the wage share and an improvement of overall distribution in the UK after the crisis, this did not come true for the wage share because workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power was depressed, according to our data inspection. This finding is broadly in line with the observation by Branston et al. (2014), who found that during the recessionary period of 2008–11, the degree of monopoly in the UK manufacturing and retail sectors increased. This has then contributed to depressing the wage share and raising the profit share in these sectors and in the economy as a whole. According to our analysis, it has been in particular the deterioration of the workers’ and trade unions’ bargaining power, as a determinant of the degree of monopoly or the mark-up, which has caused this development.

4.3 Spain

4.3.1 Spain Before the Crisis

To recall our findings in Sect. 2, the Spanish economy before the crisis saw a tendency of the adjusted wage share to fall. This was accompanied by roughly constant Gini coefficients both for the market and for the disposable income of households, and by an increase in top income shares. Let us now focus again on the contribution of financialisation to this development following the model outlined in Sect. 3.Footnote 8

For the study of the first channel, the importance of the financial corporate sector, we have first looked at the sectoral shares of the total economy. There was a slightly growing relevance of the financial sector in the Spanish economy during the early 2000s before the Great Recession , however, starting from lower values than in the USA or the UK . In addition, the share of the non-financial corporate sector in gross value added increased before the crisis, whereas the share of households, i.e. non-corporate business, declined, and the share of the government remained roughly constant. Simultaneously, the profit share of the financial corporate sector increasingly exceeded the profit share of the non-financial corporate sector. The sectoral composition channel of financialisation as such should have contributed to the fall in the aggregate wage share , if we can assume that the adjusted wage share in the non-corporate sector, as part of the household sector in the national accounts, was lower than in the financial corporate sector.Footnote 9

Looking at the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel for the Spanish economy, we have found a slight decline of the net property income share in national income in the 2000s before the crisis. Therefore, from this perspective, no upward pressure on the mark-up, and hence no downward pressure on the wage share , was imposed. Falling financial overheads/rentiers’ profit claims rather allowed for a rise in the wage share and also the share of retained earnings in the years immediately before the crisis. However, this was only possible because the increase in the share of dividend incomes associated with increasing financialisation and shareholder value orientation of management was more than compensated by a simultaneous fall in the share of net interest incomes.

With regard to the bargaining power channel, we have observed a significant improvement in the rate of unemployment in the early 2000s. However, the already very low union density rate fell further in the early 2000s, and particularly the high bargaining coverage rate deteriorated significantly. Employment protection and unemployment benefits replacement rates did not see significant changes. On the other hand, household indebtedness more than doubled in the early 2000s, and trade openness increased significantly from the mid-1990s until the crisis.

Finally, looking at property income received and paid in relation to the operating surplus of non-financial corporations, we have found a remarkable shift towards shareholder value orientation and short-termism of management, which was detrimental to the bargaining power of workers at the corporate level. With regard to property income received, we have observed a considerable rise, driven mainly by the increase in distributed income of other corporations, i.e. dividends, indicating a rising relevance of financial investment s as compared to real investment . In turn, regarding the property income paid, we have found that the relevance of total distributed property income increased vigorously in the early 2000s until the crisis, driven by dividend and interest payments, indicating both rising shareholder value orientation and rising indebtedness of corporations. Therefore, although unemployment rates in Spain decreased in the years before the crisis, several other criteria indicate the falling bargaining power of workers in this period, explaining the tendency of the wage share to fall from the early 1990s until the crisis.

Summing up, the fall in the wage share in Spain before the crisis can thus be related to a change in the sectoral composition towards the financial corporate sector and to the fall of workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power , whereas there has been no indication for the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel to have had an effect.

4.3.2 Spain in the Course of and After the Crisis

Since the crisis, the tendency of the wage share to decline in Spain has continued, whereas top income shares have fallen, but Gini coefficients have continued to rise.

Looking at the three channels through which financialisation may affect income shares, we have found that, after the crisis, the share of financial corporations in gross value added has declined, as has the profit share in this sector, which has even fallen below the profit share of the non-financial corporations. The sectoral composition channel would have thus allowed for an increase in the wage share in national income.

However, the share of net property income in net national income has started to rise again after the crisis, driven, in particular, by an increase in the share of dividend income. Simultaneously, the share of retained earnings has remained constant and even slightly increased, which means that labour has had to bear the burden of rising overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims.

This has been made possible by a further spectacular decline in bargaining power of workers and trade unions , as our indicators have shown, both for the aggregate and for the corporate level. Unemployment has more than doubled in the course of the crisis, employment protection has decreased, in particular, for temporary contracts, and household debt -to-GDP ratios and trade openness have slightly increased. Furthermore, the shareholder value orientation of management of non-financial corporations has also risen considerably since the crisis. The relevance of property income received has gone up, driven by dividends received, and also the dividends paid have risen.

Summing up the case of Spain , we can say that the sectoral composition channel would have allowed for a rise in the wage share and an improvement of overall distribution after the crisis. However, this distributional space could not be exploited by labour because workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power has been further depressed, in particular, by austerity policies and high unemployment ,Footnote 10 as well as by rising shareholder value orientation at the non-financial corporate level. Therefore, the wage share has continued to fall, and it has been the distributional position of rentiers , but also retained earnings of firms, which have benefitted so far.

4.4 Germany

4.4.1 Germany Before the Crisis

As we have seen in Sect. 2, the German economy before the crisis saw a tendency of the adjusted wage share to fall. This was accompanied by a rise in top income shares, in particular, in the period immediately before the crisis, and increasing Gini coefficients both for market income and for disposable income of households. We will now present the contributions of financialisation to this development following the model from Sect. 3.Footnote 11

Checking the relevance of the channels for the influence of financialisation on functional income shares before the crisis, with respect to the first channel, we have found that neither the profit share of the financial corporate sector was higher than the profit share in the non-financial corporate sector in the period of the increasing dominance of finance starting in the early/mid-1990s, nor was there a shift of the sectoral shares in gross value added towards the financial sector, which remained roughly constant at a low level. However, the share of the government sector in value added saw a tendency to decline, from close to 12 per cent in the mid-1990s to below 10 per cent in 2007. Similarly, the share of the household sector, containing non-corporate business, declined from around 25 per cent in the early 1990s to below 22 per cent in 2007, whereas the share of the non-financial corporate sector increased by 5 percentage points in the same period. Ceteris paribus, this change in sectoral composition means a fall in the aggregate wage share and a rise in the aggregate profit share because the government sector is a non-profit sector in the national accounts, and the adjusted wage share in the household sector should be higher than in the corporate sector. However, the financial corporate sector was not involved in this channel of redistribution.

Downsizing the share of the government sector in Germany was a consequence of restrictive macroeconomic policies, and most importantly restrictive fiscal policies, focussing on price stability, improving external price competitiveness and balanced budgets in the run-up to the introduction of the euro in 1999, and then, in particular, during the stagnation period of the early and mid-2000s. Apart from this sector composition effect, restrictive macroeconomic policies had another important effect on the wage and labour income shares via its depressing impact on the bargaining power of workers and trade unions , as we will argue below.

Regarding the second channel, the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we have found several developments supporting its validity in the case of Germany . There has been substantial evidence that the increase in the profit claims of rentiers came at the expense of the workers’ share in national income. From the 1990s, after German re-unification, until the Great Recession , the fall in the wage share benefitted mainly the rentiers’ income share. Only during the short upswing before the Great Recession did the share of retained earnings also increase at the expense of the wage share. Decomposing the rentiers’ income share, it has become clear that the increase was exclusively driven by a rise in the share of dividends, starting in the mid-1990s, when we observed an increasing dominance of finance and shareholders in the German economy.

With respect to the third channel, the depression of workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power , we have found that several indicators apply to the development in Germany before the crisis. Starting in the early/mid-1990s, downsizing the government sector, as shown above, and the switch towards restrictive macroeconomic policies focussing exclusively on achieving low inflation , high international price competitiveness and (close to) balanced public budgets meant low growth and rising unemployment .Footnote 12 Policies of deregulation and liberalisation of the labour market (Hartz-laws , Agenda 2010) explicitly and successfully aimed at weakening trade union bargaining power through lowering unemployment benefits (replacement rates and also duration), establishing a large low-paid sector, as well as reducing trade union membership, collective wage bargaining coverage and coordination of wage bargaining across sectors and regions (Hein and Truger 2005). As a result of the reforms, unemployment benefits were drastically reduced, so that net- as well as gross-replacement rates declined considerably in the early 2000s. While indicators for employment protection showed a slight increase in employment protection for regular contracts from 2000 onwards, temporary contracts were heavily deregulated, contributing to the emergence of a dual labour market in Germany. The weakening of trade unions since the mid-1990s could be seen by the decline in membership, i.e. union density, but in particular by the decline in bargaining coverage, which fell from 74 per cent in the mid-/late 1990s to only 64 per cent until the crisis. Furthermore, the trade and financial openness of the German economy increased significantly and put pressure on trade unions through international competition in the goods and services markets and through the effect of delocalisation threat. Trade openness increased by more than 30 percentage points of GDP from the early 1990s until the crisis. However, household debt -to-GDP ratios remained low by international comparison and only slightly increased before the crisis.

Looking at shareholder value orientation and bargaining power at the non-financial corporate level, we have found that shareholder value orientation and short-termism of management of non-financial corporations increased significantly in the period before the crisis, thus increasing the pressure on workers and trade unions and constraining their bargaining power. A rising relevance of financial profits by non-financial corporations indicated an increased preference of management for short-term profits obtained from financial investment , as compared to profits from real investment , which might only be obtained in the medium to long run. This increase was driven by growing interest payments received in a period of low interest rates and by an increase in dividend payments obtained, and, furthermore, by reinvested profits from FDI . Turning to distributed profits, we have observed a rise in the importance of distributed property income in the period before the crisis. This increase was driven almost exclusively by an increase in distributed income of corporations, i.e. dividends, whereas interest payments in relation to the gross operating surplus stagnated or even declined.

Summing up the German case before the crisis, it can be argued that the fall in the wage share was mainly caused by the rise in financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims, and, in particular, by the significant fall in workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power . There was no change in sectoral composition towards the financial sector; however, the changes at the expense of the government and maybe the household sector have contributed as well to the fall in the wage share of the economy as a whole.

4.4.2 Germany in the Course of and After the Crisis

In the course and after the crisis, the wage share in Germany has remained roughly constant, whereas Gini coefficients for households’ market and disposable income have continued to rise slightly. Lack of data does not allow for any conclusion regarding the post-crisis tendency of top income shares. Reviewing the three channels through which financialisation may affect income shares, we have found the following results.

First, the sectoral composition of the German economy has remained roughly stable, and the profit share in the financial sector has remained below the one in the non-financial corporate sector, with an increasing gap between the two. This should have contributed to a rising wage share for the economy as a whole.

Second, the pressure via the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel on the wage share has declined and the property incomes share, as well as the share of income going to rentiers in terms of dividends, has remained constant. This has allowed the wage share to remain stable and the share of retained earnings to rise.

Third, looking at the workers’ bargaining power channel, labour market indicators have indicated mixed results. Unemployment rates have fallen significantly after the crisis, due to the quick recovery of the German economy from the crisis (Detzer and Hein 2016). However, several labour market indicators have changed further to the disadvantage of workers and trade unions . Trade union density and wage bargaining coverage have further declined, unemployment benefit replacement rates have fallen further and employment protection legislation has remained constant. Trade openness further increased after the crisis, but the already low household debt -to-GDP ratio has fallen. Furthermore, the introduction of a legal minimum wage in 2015 (Amlinger et al. 2016) should have had a positive impact on workers’ and trade unions’ bargaining power. At the non-financial corporate level, shareholder value orientation has fallen and the pressure on labour has been relieved, as the fall in the relevance of both financial profits received and financial profits paid out has indicated, and in dividends paid out, in particular.

Summing up, during and after the crisis, the pressure through the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel on the wage share has relaxed and workers’ bargaining power has somewhat recovered, by the reduction of shareholder value orientation at the non-financial corporate level and, in particular, by the rapid recovery of the German economy from the crisis providing falling unemployment rates (Detzer and Hein 2016; Dodig et al. 2016). Therefore, redistribution at the expense of the wage share has come to a halt. However, neither this does imply that the trend towards a falling wage has actually been reversed, nor has rising inequality of household incomes, as indicated by the Gini coefficients for market and disposable income, come to a stop.

4.5 Sweden

4.5.1 Sweden Before the Crisis

Sweden had seen a tendency of the wage share to fall, and the top income share and the Gini coefficients for market and disposable incomes to rise before the crisis, as we have discussed in Sect. 2. However, the top income shares and the Gini coefficient for disposable income were the lowest in our country set.Footnote 13 Let us now apply our model from Sect. 3 to assess the effects of financialisation on factor income shares.

Regarding the relevance of the sector composition channel in Sweden , we have found that there was no shift of the sectoral shares in gross value added towards the financial sector prior to the crisis. In fact, it was the non-financial sector that increased its share slightly at the expense of households and the government. However, the profit share of the financial corporations was higher than the profit share of the non-financial corporation in the whole studied period, but with some convergence tendency observed up to the crisis. Through this channel, there was hence no downward pressure of financialisation on the aggregate Swedish wage share .

With respect to the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we also did not find much pressure on the wage share before the crisis. The share of net property income in net national income was broadly stationary before the crisis, with a slight fall in the early 2000s before rising back to its share of the 1990s until 2007. It seems that prior to the crisis the movements in the share of wages were rather inversely related to the share of retained earnings in the short run, with only a slight fall in the medium run. Looking at the decomposition of rentiers’ income, we have found a slight increase in the share of dividends in the early 2000s, which, however, was compensated for by a fall in the share of net interest income. Therefore, the financial overheads/rentiers’ profit claims channel was of no relevance in Sweden before the crisis.

For the bargaining power channel, we have found some deterioration for labour market indicators before the crisis. Unemployment rates saw a tendency to rise until the crisis. The union density rate fell by almost 10 percentage points between 1990–4 and 2005–9, but the bargaining coverage remained at a very high level. Employment protection, while remaining constant for regular contracts, was heavily downsized for temporary contracts. Simultaneously, the net replacement rates, excluding and including social benefits, were reduced, too. Furthermore, the trade openness of the Swedish economy continuously increased until the crisis, putting pressure on workers’ income claims. The same was true for the household debt -to-GDP ratio.

The fall in bargaining of workers and trade unions as indicated by the development of some labour market institutions and by rising trade openness was further reinforced by rising shareholder value orientation of management at the non-financial corporate level. Looking again at our two indicators, we have found that in Swedish non-financial corporations, total property income received in relation to the gross operating surplus almost doubled between 1995 and 2007. This remarkable increase was primarily driven by the distributed income of corporations, i.e. dividends, while the interest income lost in significance following the decrease in the interest rates in late 1990s. The increase in relevance of dividend payments obtained suggests that there was a period of increasing importance of the financial investment as compared to real investment in Sweden in the years preceding the crisis. With regard to the second indicator of increasing shareholder value orientation of management—the growing relevance of profits distributed to shareholders—such a development could also be observed in Swedish non-financial corporations. Distributed property income paid increased significantly, especially between 2005 and 2007. This increase could be mainly attributed to the increase in distributed income of corporations, whereas the relevance of interest fell and later stagnated.

Summing up the Swedish case before the crisis, we can argue that the slight fall in the wage share before the crisis can be attributed in particular to the pressure on workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power , whereas the sectoral composition and financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel were irrelevant.

4.5.2 Sweden in the Course of and After the Crisis

Since the crisis, the wage share in Sweden has stabilised. The same seems to be true for the Gini coefficients for household incomes and the top income shares.

Looking at the sectoral composition channel for functional income distribution , there has not been much of a change since the crisis. And also profit shares in the financial and the non-financial corporate sectors have remained rather stable.

With regard to the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, we have seen a modest increase in the share of net property incomes in national income, driven by the share of dividend incomes. However, this has not come at the expense of the wage share , but rather at the expense of the share of retained earnings.

Finally, the results regarding the bargaining power channel have been mixed. On one hand, looking at labour market indicators, we have observed a slight rise in unemployment rates, a decline in union density and in bargaining coverage. Furthermore, employment protection for employees on temporary contracts has been further weakened, and for unemployment benefits, a further decline in the net replacement ratios has been observed. Also the household debt -to-GDP ratio has further increased. All this has further weakened workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power after the crisis. However, on the other hand, trade openness has slightly fallen but remained at a high level. Furthermore, at the non-financial corporate level, the shareholder pressure on management has declined significantly. This has been indicated by the significantly declining relevance of financial profits relative to the operating surplus of non-financial corporations, driven by a fall in dividends received. We have also observed a substantial decrease in the relevance of total distributed property income, in particular, the decrease in the relevance of dividend payments.

Summing up, in the course and after the crisis neither the sectoral composition nor the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel put any pressure on the Swedish wage share . Furthermore, the rapid recovery of the Swedish economy after the crisis (Dodig et al. 2016; Stenfors 2016) and the decline of shareholder value orientation in the non-financial corporate sector have been sufficient to stabilise workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power . This prevented a further fall in the wage share and stabilised functional income distribution between capital and labour, as well as the indicators for household income inequality , however, without reversing the pre-crisis trends.

4.6 France

4.6.1 France Before the Crisis

As we have seen in Sect. 2, before the crisis the French economy witnessed a tendency of the adjusted wage share to fall and of the top income shares to rise, whereas the Gini coefficients for households’ market and disposable incomes remained roughly stable.Footnote 14 Again, we apply our model from Sect. 3 in order to assess the effects of financialisation on functional income shares.

Reviewing the sectoral composition channel for the distributional effects of financialisation , we have found that the share of the financial corporate sector in gross value added slightly declined from the early 1990s until the crisis, which was associated with a slight increase in the share of non-financial corporations. The profit share in the financial corporate sector decreased from the 1990s until the years before the crisis, when it reached the level of the non-financial corporate sector. Therefore, we can deny any relevance of the sectoral composition channel for the fall in the aggregate adjusted wage share in France .

For the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profits claim channel, we have also found no effect on the aggregate wages share. From the early 1990s until the crisis, the share of rentiers’ income (net property income) in net national income rather saw a slight tendency to fall, which allowed for a slight increase in the share of retained earnings, associated with only a very modest fall in the wage share . Looking at the composition of rentiers’ income, we have seen a rise in the share of dividend incomes, which, however, was overcompensated by a fall in the share of net interest income in net national income.

Regarding the bargaining power channel, we have found mixed results for the period from the early 1990s until the crisis. Unemployment rates had a tendency to fall before the crisis. Union density was particularly low and even slightly decreased before the crisis. However, bargaining coverage was rising and almost reached 100 per cent before the crisis, due to the French legal extensions of bargaining agreements. Employment protection decreased somewhat, but only for temporary contracts. Unemployment benefit replacement rates also slightly decreased. Trade openness modestly increased, compared to some of the other countries in our data set, and household debt -to-GDP ratios increased somewhat, but from a very low level in international comparison.

Finally, looking at our two indicators for shareholder value orientation of management in non-financial corporations, we have found strong support for both in the run-up to the crisis. The share of property incomes received relative to the operating surplus strongly increased, indicating rising relevance of financial investment as compared to investments in the real capital stock of the firm. The property incomes distributed in relation to the operating surplus also increased, driven in particular by rising dividend payments to shareholders. Each of these developments was detrimental to workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power on the corporate level, and thus put pressure on the wage share . This finding has been confirmed by a study by Alvarez (2015), using firm-level data of the French non-financial corporate sector for the period 2004–13. According to this study, the dependence on financial profits has been likely to decrease the wage share in non-financial corporations because of the dampening effects on labour’s bargaining power.

Summing up the French case before the crisis, we can argue that neither any sectoral composition channel nor any financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel contributed to the fall in the wage share . The latter can be related only to a fall in workers’ bargaining power , in particular, due to rising shareholder value orientation in non-financial corporations.

4.6.2 France in the Course of and After the Crisis

France is the only country in our data set that has seen a tendency of the wage share to increase in the course and after the crisis. Furthermore, the top income share has remained constant, and the Gini coefficients for households’ market and disposable incomes have even seen a tendency to fall.

Examining our channels through which financialisation might affect income shares, we have found that the sectoral composition has remained roughly constant in the period after the crisis. For the profit share of financial corporations, a slight recovery has been observed so that it has again exceeded the profit share of non-financial corporations since 2010. This should have put some downward pressure on the aggregate wage share , but the sectoral composition channel as such has had no effect on the development of income shares after the crisis.

Regarding the financial overheads /rentiers ’ profit claims channel, the share of financial profits in national income has declined considerably, indicating a fall in financial overheads/rentiers’ profit claims, and the share of dividends has also fallen slightly. The wage share has risen considerably, associated with a fall of the share of retained earnings. This is pointing to improvements in workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power .

Looking at our indicators for bargaining power , we have observed that unemployment rates have slightly increased, but bargaining coverage has remained at a level close to 100 per cent, while employment protection has been downsized somewhat, and the unemployment benefit replacement rates have remained constant. Furthermore, the trade openness of the French economy has only slightly increased, and the household debt -to-GDP ratio has increased somewhat, but is still the lowest in our data set. Most importantly, however, the degree of shareholder value orientation of management of non-financial corporations has declined considerably. The relevance of property income received has decreased, as has the importance of property incomes paid out, in particular, the dividends.

Taken together, the decline in financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims and the stabilisation and partial improvement of workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power , associated with the fall in shareholder value orientation of non-financial corporations, seem to have allowed for the wage share to increase somewhat after the crisis—and also for income inequality at the individual or household level to decrease somewhat.

5 Comparison

With the help of Table 2 we can now compare our country-specific findings and reassess the relationship between financialisation and income distribution , applying the Kaleckian theoretical approach towards the determination of functional income distribution in finance-dominated capitalism outlined in Sect. 2

.

Looking first at the period from the early 1990s until the crisis, each of the countries saw a tendency of the adjusted wage share to decline, with the only exception of the UK , where the tendency remained rather constant in this period. Top income shares were rising in each of the countries. Gini coefficients for market and disposable income also increased, with the exception of Spain and France , where they remained roughly constant. Generally, ‘debt -led private demand boom’, ‘export-led mercantilist’ and ‘domestic-demand-led’ countries had to face similar developments in terms of income redistribution.

Assessing the channels through which financialisation may affect functional income shares, some differences are obvious. Each of the ‘debt -led private demand boom’ countries before the crisis, the USA , the UK and Spain , saw a change in the sectoral composition of the economy towards the financial corporate sector with higher profit shares . However, only in the USA financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims were rising, whereas in the UK and Spain, the reverse was true. The fall in workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power contributed significantly to the fall in the wage share in the USA and in Spain. In the UK, however, there was no such general fall in workers’ bargaining power, and together with the reduction in financial overheads and rentiers’ profit claims, this allowed for a stable wage share before the crisis.

For the ‘export-led mercantilist’ countries, Germany and Sweden , and for the ‘domestic-demand-led’ economy, France , the fall in the wage share before the crisis cannot be attributed to a change in the sectoral composition of the economy towards a financial sector with higher profit shares . Moreover, only in Germany have we found a rise in financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims, whereas in Sweden there was no such effect and in France financial overheads and rentiers’ profit claims were rather falling before the crisis. For Germany and Sweden, the fall in workers’ and trade unions ’ bargaining power is a major explanation for the fall in the wage share before the crisis, and for France, a falling wage share can only be related to falling workers’ bargaining power in the non-financial corporate sector due to rising shareholder value of management.

For the period since the crisis, the former ‘debt -led private demand boom’ economies, the USA , the UK and Spain , have seen a further decline in the wage share . Top income shares and Gini coefficients for the distribution of household incomes, however, do not show a unique pattern in this group. Top income shares have only been rising in the USA but falling in the UK and Spain, and Gini coefficients have been rising in the USA and Spain, but have remained constant in the UK.

Explaining the fall in the wage share after the crisis, what these countries have in common is the deterioration of workers’ bargaining power , applying both economy-wide indicators and specific indicators for shareholder value orientation of management and hence bargaining power of workers in the non-financial corporate sector. Only in the USA did we find a few indicators among several others which show an improvement of workers’ bargaining power, albeit from a low level. In addition, the post-crisis fall in the wage share in the USA can also be attributed to the further change in the sectoral composition towards the financial corporate sector with a higher profit share, as well as to the rise in financial overheads and rentiers ’ profit claims. In the UK , however, these two channels would rather have allowed for a rise in the wage share. This has also been true for the change in the sectoral composition in Spain , whereas the rise in financial overheads and rentiers’ profit claims has contributed to the fall in the wage share in that country.

The ‘export-led mercantilist’ countries, Germany and Sweden , as well as the ‘domestic-demand-led’ country, France , managed to stop the tendency of the wage share to fall after the crisis. In France, the wage share has even seen a rising tendency since then, whereas in Germany and Sweden, it has remained roughly constant. Top income shares have remained constant in Sweden and France (for Germany there is a lack of data), and the Gini coefficients for household incomes have been falling in France, while they remained constant in Sweden and have continued to rise in Germany.