Abstract

This chapter describes the main vegetation units of Península Valdés at scale 1:250,000 with emphasis on relevant physiognomic and floristic characteristics. Based on photogrammetry (aerial photograph pairs 1:60,000) and ground check, 18 dominant singular plant species arrangements (vegetation units) were identified reflecting the variety of environmental conditions at a mesoscale (1:250,000) within Península Valdés. At sites selected for ground check, floristic–physiognomic census including a complete floristic plant species list with the relative abundance of each species were performed. After that, censuses of species abundance were ordered by principal component analysis. The layer structure, the main life forms and the dominant species for each identified and mapped vegetation unit were described. Among them, we identified shrubby vegetation units at northern and central Península Valdés and, grassy vegetation units at southern Península Valdés. A map of vegetation units and some pictures of the most representative vegetation units complete the vegetation description. Moreover, this chapter includes a detailed description of the plant communities (resolution scale 1:1) characterizing four sites identified as priorities for ecosystem conservation. Priority sites for conservation are located in Salt marshes, Uplands and Plain Systems and Endorheic Basins. Some contrasts between conserved and degraded community states are also exemplified.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The phytogeographical identity of the vegetation of Península Valdés has long been discussed by various authors due to the presence of characteristic floristic elements of two different Phytogeographical Provinces. Some specialists included the vegetation of Península Valdés in the Patagonian Phytogeographical Province (Lorentz 1876; Holmberg 1898; Kühn 1922, 1930; Cabrera 1976; Soriano 1956; Morello 1958; León et al. 1998). Other researchers referred the vegetation of this portion of Patagonia to the Monte Phytogeographical Province (Hauman 1920, 1926, 1931, 1947; Parodi 1934, 1945, 1951; Castellanos and Pérez Moreau 1944). Moreover, Frenguelli (1940) and Soriano (1950) defined the vegetation of Península Valdés as an ecotone between the vegetation of both Provinces. This debate continued since more recently, Roig and Martínez Carretero (1998) included vegetation of Península Valdés in the Monte while León et al. (1998) in the Patagonian Phytogeographical Province. In this contribution, we adopt the criteria of León et al. (1998).

Probably, all these discrepancies are due to the fact that despite sharing floristic elements characteristic of both Patagonian and Monte, most of the vegetation of Península Valdés lacks of Larrea species (main floristic components of the Monte) and has an abundant and extended presence of Chuquiraga species (main floristic components in the Central District of the Patagonian Province).

2 Main Plant Adaptive Strategies

The Península Valdés is characterized by vast terraces (Uplands and Plains System, see Chapter “Late Cenozoic Landforms and Landscape Evolution of Península Valdés”) covered by discreet plant life forms arranged in a patchy structure. Native species present today are the result of plant adaptive responses to the prevailing arid conditions after the Andean uplift (see Chapter “Climatic, Tectonic, Eustatic, and Volcanic Controls on the Stratigraphic Record of Península Valdés”). These adaptive responses to aridity along with high intensity and frequency of dry winds, and relative low temperatures (Ares et al. 1990; see Chapter “The Climate of Península Valdés Within a Regional Frame”) resulted in particular structural and functional adaptations. The main life forms in Península Valdés are shrubs (evergreen and deciduous), bunch perennial grasses, and forbs (Sala et al. 1989; Golluscio and Sala 1993; Bertiller et al. 2006). Dominant evergreen shrubs show adaptations such as cushion form, small leaves, and green leafless stems. Epidermal pubescence is another adaptive feature giving a typical grey or green opaque colour to leaves. Drought deciduous shrubs may also be present in the shrubby canopy. Vegetation canopy in the northern-central Península Valdés consists of a patchily arranged shrubby matrix. Less conspicuous grass species and forbs are scattered in almost all inter-patch areas or associated to shrub patches. In contrast, sandy soils in southern Península Valdés are mainly covered by rhizomatous perennial grasses forming a continuous grass stratum with interspersed shrubs.

Most of the plant activity in the Península Valdés depends on soil water accumulated during the winter-spring precipitation period although precipitation pulses could also occur in autumn and summer (Ares et al. 1990; Barros and Rivero 1982, see Chapter “The Climate of Península Valdés Within a Regional Frame”). Increasing temperature and day length coupled with high soil moisture conditions in early spring leads to the reactivation of the vital functions in most species. This activity period is extended up to early–late summer depending on the rooting depth of the species (Bertiller et al. 1991; Campanella and Bertiller 2008). In this sense, the activity of deep rooted shrubs, both deciduous and evergreen, is more extended into the dry summer compared to that of perennial grasses with shallow rooting depth. The timing of flowering, with some exceptions, has a marked seasonality occurring only once in the year.

3 Description of the Main Vegetation Units (Scale 1:250,000)

Eighteen dominant singular plant species arrangements (vegetation units) reflect the variety of environmental conditions at a mesoscale (1:250,000) within Península Valdés (Bertiller et al. 1981). Based on photogrammetry (aerial photograph pairs 1:60,000) and ground check, 18 main vegetation units were identified in Península Valdés. At sites selected for ground check, floristic–physiognomic census (Mueller-Dombios and Ellemberg 1974) including a complete floristic plant species list with the relative abundance of each species were performed. After that, censuses of species abundance were ordered by principal component analysis. The layer structure, the main life forms and the dominant species for each identified and mapped vegetation unit were described (Bertiller et al. 1981). Nomenclature followed the Flora Patagónica (Correa 1969, 1971, 1978, 1984a, b, 1988, 1998, 1999), and was updated by the Data Base Flora Argentina (http://www.floraargentina.edu.ar/).

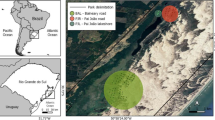

These dominant vegetation units range from shrubby steppes in the north and centre of Península Valdés to perennial grass steppes dominating in the south of Península Valdés (Fig. 1). The north of Península Valdés is mostly characterized by terraces and piedmont slopes (Uplands and Plains System, see Chapter “Late Cenozoic Landforms and Landscape Evolution of Península Valdés”) covered by shrub and grass-shrub steppes, dominated by shrubs of the genus Chuquiraga and perennial grasses of the genus Nassella and Jarava. The Great Endorheic Basins System characterizing the central portion of the Península Valdés are covered by shrub and the shrub-perennial grass steppes with predominance of shrubs (Chuquiraga spp., and Cyclolepis genistoides), and the perennial grass Nassella tenuis. The south portion of the Península Valdés is characterized by terraces covered in some places by West–East stabilized aeolian field. Terraces are colonized by patchy steppes consisting of a mosaic of perennial grass- and shrubby steppes. Stabilized aeolian field deposits are covered by perennial grass steppes with isolated shrubs and shrub steppes of Hyalis argentea. Moreover, active dunefield and playa lakes deposits without vegetation alternate with these vegetation units. Finally, coastal landforms around Península Valdés are covered by shrubby or grass-shrubby steppes.

Location of Península Valdés and Vegetation Units redrawn from Bertiller et al. (1981)

3.1 Vegetation of System A: Uplands and Plains

3.1.1 Vegetation of the Terrace Level I

-

Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae and Schinus johnstonii ( VU17, Fig. 1 )

This shrubby steppe is the dominant vegetation unit in the Terrace level 1 occupying a narrow band in the Istmo Carlos Ameghino. The total vegetation cover is 40–50% consisting of a dominant shrubby stratum (ca. 40% cover, 50–200 cm tall) mostly represented by C. avellanedae and S. johnstonii along with Condalia microphylla and Prosopidastrum globosum. The other plant layers are a dwarf shrub stratum (1–5% cover, 5–10 cm tall) dominated by Acantholippia seriphioides and an herbaceous layer dominated by herbaceous perennial forbs: Boopis anthemoides, Hoffmannseggia trifoliata, and Perezia recurvata and by perennial and annual grasses N. tenuis, Pappostipa humilis, Jarava neaei, Pappostipa speciosa, Poa ligularis and Schismus barbatus.

3.1.2 Vegetation of the Terrace Level II

-

Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga erinacea ssp. hystrix and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses ( VU13 , Figs. 1 and 2 a)

Fig. 2 Views of the main Vegetation Units of Península Valdés. a Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga erinacea ssp. hystrix and Chuquiraga avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU13); b Perennial grass steppe of Piptochaetium napostaense, Nassella tenuis and Plantago patagonica (VU2); c Mosaic VU2–VU5 (Shrub-perennial grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae and Nassella tenuis; d Shrub-perennial grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae and Nassella tenuis (VU5); e Shrub-perennial grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae and Nassella tenuis (VU5); f Perennial grass steppe of Sporobolus rigens and Nassella tenuis (VU1); g Shrub steppe of Hyalis argentea (VU6); h Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga erinacea ssp. hystrix, Cyclolepis genistoides, and Chuquiraga avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU16); i Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, Larrea divaricata and Nassauvia fuegiana (VU14); j Shrub steppe of Cyclolepis genistoides, Chuquiraga avellanedae, and Atriplex lampa (VU15)

This vegetation unit is mostly characteristic of central Península Valdés dominating the Terrace level 2 as well as piedemont pediments and bajadas (System B, see Sect. 3.2). The total plant cover is 60–80% and consists of a mosaic of shrubby and perennial grass patches. Shrubby patches are dominated by a tall layer (50% cover, 50–180 cm tall) represented by C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, C. avellanedae along with Lycium chilense, S. johnstonii, C. microphylla, and Brachyclados megalanthus with dwarf shrub and herbaceous perennial species (5–10 cm tall) covering 5% of the soil (H. trifoliata, Baccharis darwinii, P. recurvata, Tetraglochin caespitosum, and A. seriphioides). Perennial grass patches (15–20% cover, 5–10 cm tall) are dominated by N. tenuis, Piptochaetium napostaense, P. speciosa, P. humilis, with J. neaei, P. ligularis, with annual grasses (S. barbatus and Bromus catharticus) and the annual forb Daucus pusillus.

3.1.3 Vegetation of the Terrace Level III

The Terrace Level III is mainly covered by a two-phase mosaic (mosaic VU2–VU5, Fig. 1) consisting of the perennial grass steppe of P. napostaense, N. tenuis, and Plantago patagonica (VU2) and the shrub-perennial grass steppe of C. avellanedae and N. tenuis (VU5) characteristic of Terrace Level IV (see below). Also, pure patches of VU5 and a mosaic (VU1–VU6, Fig. 1) composed of the perennial grass steppe of Sporobolus rigens and N. tenuis (VU1) and the shrub steppe of H. argentea. (VU6), characteristic of the Stabilized aeolian fields (see Sect. 3.1.7), may cover in small patches Terrace Level III.

-

Perennial grass steppe of P. napostaense and N. tenuis with P. patagonica and isolated shrubs of C. avellanedae ( VU2, Figs. 1 and 2 b)

This vegetation unit has a total plant cover of 60–70% and is dominated by a conspicuous herbaceous layer (40–50% cover, 20 cm tall) characterized by the perennial grasses P. napostaense and N. tenuis accompanied by B. catharticus, S. barbatus, and the annual herb P. patagonica. The shrubby layer (15% cover, 50–200 cm tall) is dominated by C. avellanedae along with S. johnstonii, L. chilense, and Discaria americana. There are also scattered dwarf shrubs (Baccharis melanopotamica and T. caespitosum) and herbaceous perennial herbs (Paronychia chilensis and H. trifoliata) covering 5% of the soil with a height ca. 10 cm. This vegetation unit is mostly patchily associated (mosaic VU2–VU5, Fig. 1) with the shrub-perennial grass steppe of C. avellanedae and N. tenuis (VU5), characteristic of the central portion of the Península Valdés (Fig. 2c).

3.1.4 Vegetation of Terrace Level IV

The dominant vegetation at Terrace Level IV consists of shrub-grass steppes and shrubby steppes with perennial grasses. The most conspicuous vegetation unit occupying these terraces in central Península Valdés is the shrub-perennial grass steppe of C. avellanedae and N. tenuis (VU5) while in the northern areas vegetation is represented by the shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. microphylla (VU9).

The total plant cover is ca. 50% with a patchy arrangement consisting of shrubby and perennial grass patches. Shrubby patches (25% cover, 50–60 cm tall) are dominated by C. avellanedae along with S. johnstonii and L. chilense. Perennial grass patches (20–25% cover, 10 cm tall) are dominated by N. tenuis and P. napostaense with P. ligularis and Nassella longiglumis. Scattered dwarf shrub and herbaceous species (5% cover, 10 cm tall) represented by H. trifoliata, P. chilensis and P. recurvata are immersed in the perennial grass patches.

-

Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. microphylla ( VU9, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit has a plant cover of 50–60% with a presence of shrubby and grass layers. The shrubby layer (40% cover, 40–120 cm height) is dominated by C. avellanedae, C. microphylla, and P. globosum along with B. megalanthus, L. chilense and S. johnstonii. The grass layer (15% cover, 15 cm height) is represented by N. tenuis, P. speciosa, J. neaei, P. napostaense, N. longiglumis and S. barbatus.

3.1.5 Vegetation of Terrace Level V

This Terrace level is covered by the shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and N. tenuis (VU5), characteristic of the Terrace Level IV, and by a two-phase mosaic (mosaic of this vegetation unit and the perennial grass steppe of P. napostaense and N. tenuis with P. patagonica and isolated shrubs of C. avellanedae (VU2), characteristic of Terrace Level III (VU2–VU5, Fig. 1).

3.1.6 Vegetation of Terrace Level VI

The Terrace Level VI consists of shrub-grass steppes and shrubby steppes with perennial grasses. Three vegetation units colonize this terrace level: The shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. microphylla (VU9) also characteristic of Terrace Level IV (see Sect. 3.1.4), the shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. erinacea ssp erinacea (VU8), and the shrub steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU13), characteristic of Terrace Level II.

-

Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. erinacea ssp. erinacea ( VU8, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit is characteristic of terrace levels at the northeastern Península Valdés. The total plant cover is 60–80% with two shrubby and a grass layers. The tall shrubby layer (30–40% cover, 50–100 cm height) is dominated by C. avellanedae and C. erinacea ssp. erinacea, accompanied with L. chilense, C. microphylla, P. globosum and S. johnstonii. The dwarf shrub layer (5% cover, 5–15 cm height) is represented by P. chilensis, H. trifoliata, B. darwinii and P. recurvata. The grass stratum (15–30% cover, 5–20 cm height) is dominated by N. tenuis, J. neaei, P. speciosa and P. patagonica. Other grasses less represented in this layer are P. humilis, S. barbatus, P. ligularis, Vulpia myuros f. megalura and P. napostaense.

3.1.7 Vegetation of the Stabilized Aeolian Fields

The Stabilized aeolian fields are covered by two main vegetation units: the perennial grass steppe of S. rigens and N. tenuis (VU1) and the dwarf shrub steppe of H. argentea (VU6). These vegetation units are mostly spatially arranged in a two-phase mosaic.

The plant canopy covers between 70 and 80% and consists of a continuous perennial grass layer, 30 cm tall, covering 50–60% of the soil. This layer is dominated by S. rigens and N. tenuis with P. napostaense, Panicum urvilleanum and Poa lanuginosa. Scattered shrubs (Lycium spp., Baccharis divaricata) or perennial herbaceous plants (P. chilensis) are immersed in the perennial grass matrix covering between 10 and 30%.

-

Dwarf shrub steppe of H. argentea ( VU6 )

This vegetation unit is patchily arranged in a mosaic (V1–V6, Figs. 1 and 2g) with the perennial grass steppe of S. rigens and N. tenuis (VU1). The plant cover varies between 70 and 90% and is characterized by a conspicuous shrubby layer dominated by the small shrub H. argentea (65–85% cover, 50 cm tall). This species may be accompanied by other shrubs (B. divaricata) or by dwarf shrubs (A. seriphioides) covering not more than 5% of the soil. S. rigens, S. barbatus and P. lanuginosa are the most frequent components of the herbaceous layer (5–10% cover, 5–25 cm tall).

3.2 Vegetation of System B: Great Endorheic Basins

3.2.1 Vegetation of the Piedmont Pediment and Bajada

Vegetation of Piedmont pediments and bajadas is mostly represented by the shrub steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU13), characteristic of the Terrace Level II (Fig. 2e) and small patches of the shrub steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, C. genistoides and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU16).

-

Shrub steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, C. genistoides, and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses ( VU16, Figs. 1 and 2 h)

The total plant cover is 40–60% and consists of a shrubby stratum (30–40% cover, 60–100 cm height) dominated by C. avellanedae and Mulinum spinosum along with C. erinacea ssp. hystrix and C. genistoides. The dwarf shrub layer (5% cover, 5–10 cm tall) is represented by A. seriphioides and P. recurvata. The grass layer (5–10 cm tall) covering 5% of the soil is formed by the perennials P. humilis, J. neaei, N. tenuis, and P. speciosa accompanied by the annual S. barbatus.

3.3 Vegetation of the System C: Coastal Zone

3.3.1 Vegetation of the Coastal Piedmont Pediment

The vegetation of the Coastal piedmont pediment is highly heterogeneous consisting of shrub-perennial grass steppes of C. erinacea ssp. erinacea and N. tenuis (VU4) and shrub steppes with highly variable species composition: Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae, Larrea divaricata and Nassauvia fuegiana (VU14), shrub steppe of Senecio filaginoides and M. spinosum (VU12), Shrub steppe of C. genistoides, C. avellanedae, and Atriplex lampa (VU15), Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and M. spinosum (VU11), and Shrub steppe of L. divaricata, C. avellanedae and P. globosum (VU18), the shrub steppe of C. avellanedae and C. microphylla (VU9), characteristic of Terrace Level VI, the shrubby steppe of C. microphylla and L. chilense (VU7), and the shrub steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix and C. avellanedae with perennial grasses (VU13), characteristic of the Terrace Level II. Also, small patches of the perennial grass steppe of P. napostaense, and N. tenuis with P. patagonica and isolated shrubs of C. avellanedae (VU2) cover this landform.

-

Shrub - perennial grass steppe of C. erinacea ssp. erinacea and N. tenuis ( VU4, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit covers between 40 and 70% of the soil on narrow terrace flanks at northeastern Península Valdés. Plant canopy consists of three layers dominated by medium shrubs, perennial grasses, and dwarf shrubs, respectively. The medium shrub layer (40–70% cover, 80 cm height) is dominated C. erinacea along with S. johnstonii. The perennial grass layer (10–30% cover, 10 cm height) is dominated by N. tenuis, N. longiglumis and P. napostaense along with B. catharticus, P. ligularis and the annual herb P. patagonica. The dwarf shrub layer (5% cover, 10 cm tall) is composed by A. seriphioides, B. darwinii and B. melanopotamica accompanied by the perennial herbs H. trifoliata and B. anthemoides.

This vegetation unit is characteristic of the Golfo San José (San José Gulf) coast and appears patchily arranged in a two-phase mosaic (VU2–VU14, Fig. 1) with the perennial grass steppe of P. napostaense and N. tenuis with P. patagonica and isolated shrubs of C. avellanedae (VU2). The total plant cover is ca. 30% with two discontinuous shrubby layers and scattered grasses. The tallest shrubby layer (30% cover, 60 cm tall) is dominated by C. avellanedae along with L. divaricata, C. microphylla and S. johnstonii. The dwarf shrub stratum (4% cover, 20 cm height) is dominated by N. fuegiana and B. darwinii. N. tenuis and S. barbatus are the most common grasses covering ca. 1% of the soil.

-

Shrub steppe of S. filaginoides and M. spinosum ( VU12, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit occupies coastal piedmont pediments with aeolian deposits in the Golfo Nuevo. The total plant cover is 50% distributed in three layers. The shrubby layer (35% cover, 70–110 cm tall) is dominated by the medium shrubs M. spinosum and S. filaginoides, and the tall shrubs L. chilense and S. johnstonii. The dwarf shrub layer (10% cover, 30 cm tall) is formed by B. darwinii and B. divaricata. The lowest stratum (5% cover, 30 cm tall) is composed mostly of perennial grasses. S. rigens and P. lanuginosa dominate this layer along with J. neaei, P. humilis, and the annual grass S. barbatus.

This vegetation unit occupies coastal patches at the Golfo San José and Golfo Nuevo. The total plant cover is 50–70% with three plant layers. The shrubby layer (30–50% cover, 60–100 cm tall) is dominated by the medium shrub C. avellanedae and the tall shrub C. genistoides. The dwarf shrub layer (10–20% cover, 5–10 cm tall) consists of A. seriphioides and B. darwinii along with H. trifoliata and Gutierrezia solbrigii. Finally, the herbaceous layer (10–20% cover, 10 cm tall) is dominated by P. speciosa, P. humilis and J. neaei.

-

Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae, and M. spinosum ( VU11, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit covers about 50% of the soil at coastal areas of the San José Gulf. This unit presents three plant layers (shrub, dwarf shrub, and herbaceous layers). The shrub layer (30–35% cover, 70–120 cm tall) is dominated by C. avellanedae, M. spinosum, along with L. chilense and C. microphylla. The dwarf shrub stratum (10–15% cover, 10 cm tall) is formed by G. solbrigii and A. seriphioides. The herbaceous layer (10–20% cover, 10 cm tall) consists of perennial grasses N. tenuis, P. humilis, P. speciosa, along with the annual grasses B. catharticus and S. barbatus.

-

Shrub steppe of L. divaricata, C. avellanedae, and P. globosum ( VU18, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit covers about 50–60% of the soil at coastal areas of the Golfo Nuevo. This unit consists of three plant layers (shrub, dwarf shrub, and herbaceous layers). The shrub layer (50–60% cover, 50–120 cm tall) is dominated by L. divaricata, C. avellanedae, P. globosum and B. megalanthus along with C. microphylla, and Junellia spp. The dwarf shrub stratum (10–15% cover, 5–10 cm tall) is formed by B. darwinii, G. solbrigii, A. seriphioides and H. trifoliata. The herbaceous layer (ca. 5% cover, 5–10 cm tall) consists of perennial grasses: N. tenuis, P. humilis and J. neaei.

-

Shrub steppe of C. microphylla and Lycium spp. ( VU7, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit covers about 60% of the soil in the east coast of Península Valdés. The plant canopy consists of two layers (shrubby and herbaceous layers). The shrubby layer (30% cover, 60–120 cm height) is dominated C. microphylla, L. chilense, and C. avellanedae accompanied by Lycium gilliesianum and S. johnstonii. The herbaceous layer (30% cover, 20 cm height) is dominated by N. tenuis, J. neaei, P. humilis, P. napostaense, P. patagonica, N. longiglumis and S. barbatus.

3.3.2 Vegetation of the Beach Ridges I–IV

-

Perennial grass steppe of N. tenuis and N. longiglumis with shrubs of C. avellanedae ( VU3, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit covers about 85% of the soil at flat coast plains in Caleta Valdés and consists of three plant layers (perennial grass, dwarf shrub, and medium shrub layers). The perennial grass layer (40% cover, 20 cm tall) dominated by N. tenuis, N. longiglumis, P. napostaense with, B. catharticus, P. ligularis and the annual herb P. patagonica. The dwarf shrub layer (5% cover, 10 cm tall) consists of scattered dwarf shrubs (B. melanopotamica) accompanied by perennial herbs (P. chilensis and H. trifoliata). The medium shrub layer (40% cover, 30 cm tall) is dominated C. avellanedae along with Lycium tenuispinosum.

3.3.3 Vegetation of the Beach Ridges V

-

Shrub steppe of S. johnstonii and L. chilense ( VU10, Fig. 1 )

This vegetation unit is characteristic of a narrow coastal plain at Caleta Valdés covering about 40% of the soil with two strata (shrubby and herbaceous) equally represented. The shrubby layer (20% cover, 50–100 cm height) is dominated by S. johnstonii and L. chilense. The herbaceous stratum (20% cover, 5–20 cm height) is dominated by N. tenuis, J. neaei, P. speciosa, P. humilis along with P. ligularis and P. patagonica.

4 Priority Sites for Conservation

Within the Península Valdés four priority sites for conservation (resolution scale 1:1) may be identified: Salt marshes, Uplands and Plains, The Great Endorheic Basin and Stabilized Aeolian field and Active Dunefields. Among them salt marshes deserve particular attention since they have unique and important ecological functions such as production and transport of nutrients and organic matter, and constitute specific areas for feeding, sheltering and/or nesting of a large number of marine and terrestrial organisms. In addition, inland sites of Península such as Uplands, Endorheic Basins, and Central rangelands deserve also attention since they are mostly submitted to disturbance processes triggered by grazing and water and wind erosion affecting not only plant canopy structure but also soils and ecosystem processes and services (see Chapter “Soil Degradation in Península Valdés: Causes, Factors, Processes, and Assessment Methods”).

4.1 Salt Marshes

The salt marshes are intertidal environments developed, in general, in estuarine or marine coasts, in which the slow movement of tidal water favours the accumulation of fine sediments (Fig. 1). They are colonized by halophytic herbs, grasses or low shrubs. While the salt marshes remain exposed to air most of the day, they are subject to periodic flooding product of fluctuations in the level of the adjacent water bodies, so these halophytes are tolerant both to immersion and hypersalinity (Adam 1990; Bortolus 2010). Because of their hydrological conditions and their location between the marine and terrestrial environments (see Chapter “Groundwater Resources of Península Valdés”), the salt marshes have unique features, and they are inhabited by both marine and terrestrial organisms (Mitsch and Gosselink 2000). However, they should not be considered ecotones (i.e. transition zone between two different ecosystems), because although they are composed of species from the surrounding environments (land or sea; Bortolus 2010) the salt marshes present an assemblage of species that characterizes and defines them.

4.1.1 Vegetation Communities of Salt Marshes

Plant community zonation is probably the most conspicuous feature characterizing salt marshes at the landscape scale (Adam 1990). Most salt marsh communities plants zonate in bands parallel to the coastline with specific species compositions (Fig. 3); usually changing with the relative elevation, the distance from the seashore, and the global position (Adam 1990). Few terrestrial plant species are able to survive in the low marsh, where tidal amplitudes and inundation frequency are high. However, as substrate elevation increases, tidal amplitude decreases and inundation becomes less frequent. The highest marsh levels are commonly characterized by more complex plant communities with a large variety of ecological interactions going on (Adam 1990). Along the Atlantic coast of South America, the salt marshes show a particular geographic pattern (Bortolus et al. 2009; Idaszkin and Bortolus 2011; Idaszkin et al. 2011). The northern salt marshes (i.e. located at the parallel 42° S or lower northern) are characterized by vegetation communities that dominated by the perennial cordgrasses Spartina alterniflora and Spartina densiflora (Spartina-marshes), while in the southern salt marshes (at latitudes greater than 43° S) plant communities are dominated by the succulent shrub Sarcocornia perennis with a rare or nil presence of Spartina species across the intertidal frame (Sarcocornia-salt marshes). In the Península Valdés region, between parallels 42° S and 43° S, these two types of salt marsh vegetation community overlap their geographic distribution. A feature shared by both vegetation communities is that S. alterniflora, occupies the lowest marsh level, and S. perennis and S. densiflora the highest one. While there are several salt marshes in Península Valdés, Riacho (42° 25′ S, 64° 37′ W; Fig. 3a) and Fracasso (42° 25′ S, 64° 07′ W; Fig. 3b) are the greatest salt marshes from the Península Valdés (Bortolus et al. 2009; Idaszkin et al. 2011).

In particular, Riacho is a Spartina marsh community, where S. alterniflora inhabits the low marsh and decreases its abundance towards higher marsh levels. These higher levels are commonly dominated by S. densiflora, accompanied by the shrubs Limonium brasiliense, S. perennis and Atriplex vulgatissima (Fig. 3a). On the other hand, the Fracasso salt marsh community is a Sarcocornia-marsh, where the presence of S. alterniflora has being increasing in the last decade in the low marsh. The high marsh is dominated by S. perennis, accompanied with S. densiflora, Suaeda spp. and L. brasiliense forming isolated patches in the more elevated spots (Fig. 3b).

4.1.2 Conservation Concerns

Salt marshes are widely recognized by the unique, and important ecological functions they provide, such as the high primary productivity on and the transport of nutrients and organic matter from and to the sea (Mitsch and Gosselink 2000). Currently, they are considered as one of the most productive environments in the world, and this high production is often essential for sustaining estuarine and coastal food chains (Weinstein and Kreeger 2000). Furthermore, salt marshes are critical to the maintenance of the regional integrity for both terrestrial and marine communities, because they constitute specific areas for feeding, sheltering and/or nesting of a large number of marine and terrestrial organisms (Mitsch and Gosselink 2000; Weinstein and Kreeger 2000; Adam 2002). Migratory and endemic birds, fish, mammals and invertebrates of great ecological and economic importance (e.g. mussels, clams and snails) are examples of organisms that depend on the existence and integrity of the salt marshes to ensure their survival (Bortolus 2006; Adam 2002). Both Fracasso and Riacho salt marshes are included in the RAMSAR site of Península Valdés wetlands.

4.2 Uplands and Plains

The Península Valdés region, as other areas of the extra-andean Patagonia, has been grazed by sheep (Ovis aries) since the beginning of the last century (Ares et al. 2003). There is evidence that sheep grazing in Patagonia have had negative effects on plant communities like the reduction in total plant cover, alteration of the spatial structure of vegetation, soil degradation, and the reduction in the size of soil seed banks of herbivore-preferred species (Laycock 1995; Bertiller et al. 2002; Cipriotti and Aguiar 2005; Pazos and Bertiller 2008; Chartier et al. 2011). Despite the relative scarcity of specific studies, some of these impacts were also observed in the Península Valdés (Elissalde and Miravalles 1983; Blanco et al. 2008; Cheli 2009; Burgi et al. 2012). This raises important conservation concerns for these ecosystems considering the UNESCO World Heritage Site status of the area (Nabte et al. 2013).

A very important action taken for the conservation of representative terrestrial plant communities of the Península Valdés was the creation of strict reserves. This is the case of San Pablo de Valdés (henceforth San Pablo), a typical ranch dedicated to wool production that was converted into a wildlife reserve in 2005 by the local NGO “Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina” (Fig. 4). This reserve added 7360 ha to the scarce 5% of protected lands of the arid Patagonia (Nabte et al. 2013). The immediate management actions taken were the removal of all domestic herbivores (ca. 3500 sheep), internal fences, and all structures related to grazing management.

Location and main vegetation communities of San Pablo de Valdés. VC1. Medium shrub steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, Schinus johnstonii, Lycium ameghinoi, Menodora robusta and Acantholippia seriphioides; VC2. Shrub-grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, Nassella tenuis and Piptochaetium napostaense; VC3. Tall shrub-grass steppe of Chuquiraga erinacea ssp. hystrix, Chuquiraga avellanedae and Acantholippia seriphioides with Nassella tenuis, Piptochetium napostaense and Pappostipa speciosa; VC4. Dwarf shrub steppe of Hyalis argentea; VC5. Grass steppe of Sporobolus rigens and Nassella tenuis; VC6. Grass-shrub steppe of Sporobolus rigens, Nassella tenuis and Piptochaetium napostaense with sparse shrub patches of Chuquiraga erinacea ssp. hystrix, Acantholippia seriphioides, Mulinum spinosum and Baccharis divaricata; VC7. Dwarf shrub steppe of Hyalis argentea, Sporobolus rigens and Baccharis divaricata; VC8. Mosaic of shrub, shrub-grass, and grass steppes. White areas are Active Dune Fields without vegetation. Photographs illustrate vegetation communities VC1, VC3, VC4 and VC5 inside San Pablo (left) and in adjacent sheep ranches (right)

4.2.1 Vegetation Communities of Uplands and Plains

San Pablo encloses a unique mosaic of plant communities representing the most extended vegetation units of Terrace Levels and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits in southern Península Valdés (Fig. 4) (Codesido et al. 2005). The main vegetation communities are

-

Medium shrub steppe dominated by the shrubs C. avellanedae, S. johnstonii, Lycium ameghinoi, Menodora robusta, and A. seriphioides (VC1, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on Terrace Levels III. The total canopy cover ranges from 40 to 60%. The inconspicuous herbaceous layer is dominated by N. tenuis, P. ligularis and P. lanuginosa.

-

Shrub - grass steppe of C. avellanedae, N. tenuis and P. napostaense (VC2, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on Stabilized Aeolian field deposits. The total canopy cover ranges from 45 to 60%. C. erinacea ssp. hystrix codominates the shrub layer.

-

Tall shrub - grass steppe of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, C. avellanedae, and A. seriphioides with N. tenuis, P. napostaense and P. speciosa (VC3, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on Terrace Levels and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits. The total plant cover ranges from 50 to 60%.

-

Dwarf shrub steppe of H. argentea (VC4, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on undulated Active Dune Fields and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits. The total plant cover ranges from 80 to 90%, mostly represented by H. argentea with an incipient herbaceous layer dominated by P. lanuginosa and N. tenuis.

-

Grass steppe of S. rigens and N. tenuis (VC5, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on undulated dune fields and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits. The total canopy cover ranges from 70 to 90%. P. lanuginosa and P. urvilleanum codominate the herbaceous layer. Also sparse shrub patches of B. divaricata are immersed in the grass matrix.

-

Grass - shrub steppe of S. rigens, N. tenuis and P. napostaense with sparse shrub patches of C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, A. seriphioides, M. spinosum and B. divaricata (VC6, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on undulated dune fields and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits forming small patch mosaics with VC2 and VC5 and represents a degraded state of the grass steppe VC2.

-

Dwarf shrub steppe of H. argentea, S. rigens and B. divaricata (VC7, Fig. 4 )

This community is established on coastal undulated Active Dune Fields and Stabilized Aeolian field deposits. The total plant cover ranges from 80 to 90% with presence of sparse blowouts.

-

Mosaic of shrub, shrub - grass and grass steppes (VC8, Fig. 4 )

This plant community occupies heterogeneous landscapes associated with coastal Stabilized Aeolian field deposits and Small–Medium Closed Basins. It consists of a heterogeneous mosaic constituted by the plant communities described above. The conserved (San Pablo) and degraded (adjacent ranches) vegetation states of four of the above-mentioned plant communities are presented in Fig. 4. Additionally, Active Dune Fields without vegetation crossing eastwardly are distinctive components of the San Pablo landscape.

4.2.2 Conservation Concerns

San Pablo constitutes a unique opportunity in Península Valdés to describe the trajectory of plant communities under both livestock exclusion and grazing by native herbivores. A first vegetation survey carried out at the time of the reserve creation indicated that all these communities showed clear signs of degradation by livestock grazing (Codesido et al. 2005). Burgi et al. (2012) compared the structure and composition of plant communities VC1, VC3, VC4 and VC5 between San Pablo and adjacent ranches with sheep grazing production finding higher total plant cover, higher perennial-grass cover, and higher diversity of perennial grasses in San Pablo than in the adjacent grazed ranches (Fig. 4). Remarkably, all these changes were simultaneous with a steady increase of the guanaco density inside San Pablo (Marino et al. 2016). These results provide evidence on the need to conserve and protect terrestrial plant communities at relevant spatial scales serving as a basis for integrated management plans oriented to achieve ecological and economic sustainability under the long-standing scenarios of land degradation in Patagonia (Nabte et al. 2013; Marino et al. 2016).

4.3 The Great Endorheic Basin

A pilot area of ca. 400 km2 in the centre of Península Valdés (see site location in Fig. 5) was selected where soil erosion by water is prevalent (Fig. 5). The geomorphology of the area comprises both the Uplands and Plains as the Great Endorheic Basin Systems. It is conspicuous that the presence of accelerated erosion indicators such as pedestals, rills and bare soil on the Terrace Levels and gullies on slopes of the piedmont pediments and bajadas. On the east part, there is a large dried playa lake called Gran Salitral and central to the area there is a burnt area due to a fire occurred in February 2004. Extensive, continuous sheep grazing for wool production is the main land use of these rangelands. Six vegetation communities are dominant in the area.

Location and main vegetation communities of the Central Rangelands: VC1. Shrub-grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, Condalia microphylla, and Nassella tenuis, VC2. Shrub steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae with desert pavement, VC3. Shrub-grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, C. hystrix and Jarava and Pappostipa species, VC4. Shrub-grass steppe of Chuquiraga avellanedae, C. hystrix, Prosopidastrum globosum and Pappostipa and Jarava species, VC5. Sandy grassland of Nassella tenuis and Piptochaetium napostaense, VC6. Grassland of Nassella tenuis and Piptochaetium napostaense with shrubs of Chuquiraga avellanedae

4.3.1 Vegetation Communities of the Great Endorheic Basin

-

Shrub - grass steppe of C. avellanedae, C. microphylla, and N. tenuis ( VC1, Fig. 5 )

This community occurs along with alluvial bajadas dominated by Calciargid soils (see Chapter “Soil–Geomorphology Relationships and Pedogenic Processes in Península Valdés”). Vegetation cover is about 60–80%, where C. avellanedae and C. microphylla accounts for up to 50–60% of plant cover and occur along with B. megalanthus, L. chilense and P. globosum. Dominant grasses, N. tenuis, J. neaei, P. speciosa and P. napostaense, cover around 10–20% of the soil.

-

Shrub steppe of C. avellanedae with desert pavement ( VC2, Fig. 5 )

This community forms extensive shrublands on Terrace Levels. It is dominated by the shrub species C. avellanedae, surrounded by desert pavements. Dominant soils are Natrargids (see Chapter “Soil–Geomorphology Relationships and Pedogenic Processes in Península Valdés”). Vegetation cover ranges from 30 to over 40%; shrub cover is around 25–35%, while grasses cover 5–10%. S. johnstonii and P. globosum are secondary shrub species in these communities. Grasses such as N. tenuis, P. napostaense, and less frequently, P. humilis and P. ligularis may occur scattered in the bare soil matrix.

-

Shrub - grass steppe of C. avellanedae, C. erinacea ssp. hystrix and Jarava and Pappostipa species (VC3, Fig. 5 )

This community occurs along the Piedmont pediments, characterized by Torriorthents soils and the presence of gullies and erosion escarpments of sandstone of the Puerto Madryn Formation (see Chapter “Geology of Península Valdés”). Vegetation cover ranges from 60 to over 70%; shrub cover is around 45–55%, while grasses cover 10–20%. The most conspicuous shrubs are C. avellanedae and C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, which occur with L. chilense and S. johnstonii. Grasses such as N. tenuis, J. neaei, P. speciosa accompanied by, less frequently, P. humilis and N. longiglumis, make up the herbaceous stratum.

-

Shrub - grass steppe of C. avellanedae, C. erinacea ssp. hystrix, P. globosum and Pappostipa and Jarava species ( VC4, Fig. 5 )

This community occurs along the Terrace Levels, dominated by Haplocalcid soils and with a vegetation cover from 65 to over 85%. Shrub vegetation cover is about 50–60%, where C. avellanedae, Chuquiraga hystrix, and P. globosum account for up to 50% of plant cover and occurs along with grasses (20–30%) such as N. tenuis, J. neaei, and P. speciosa accompanied by, less frequently, P. ligularis.

-

Sandy grassland of N. tenuis and P. napostaense ( VC5, Fig. 5 ).

This community forms extensive grasslands on thin sandsheets on Terrace Levels with Haplocalcid soils. Vegetation cover ranges from 40 to over 50%; grasses (20–30%) such as N. tenuis, P. napostaense, P. speciosa, and N. longiglumis make up the herbaceous stratum. Shrub cover is around 15–25%. The most conspicuous shrub is C. avellanedae, which occurs with P. globosum and other shrubs such as S. johnstonii and L. chilense.

-

Grassland of N. tenuis and P. napostaense with shrubs of C. avellanedae ( VC6, Fig. 5 )

This community principally occurs on sandy sediment that filled the Holocene stream valleys that dissected the Coastal Piedmont Pediments with Haplocalcid soils. Vegetation cover is about 40–60%, where N. tenuis and P. napostaense accounts for up to 40–50% of grass cover and occur along with P. speciosa and Nasella longiglumis. Some shrubs (5–10%) of C. avellanedae and less frequently, P. globosum are present.

4.4 Vegetation Communities of Stabilized Aeolian Field and Active Dunefields

A pilot area is located in grazed lands in the southern portion of the Península Valdés dunefields (see site location in Fig. 6). The source of sediment for the aeolian landforms are the western sandy beaches of Golfo Nuevo where a continued supply of loose, sand-sized sediment is available to be transported inland by the prevailing westerly winds (see Chapter “Late Cenozoic Landforms and Landscape Evolution of Península Valdés”). General features in the topography of dunefields are Stabilized aeolian field (relict aeolian landforms) and mega-patches of Active sand dunes with deflation plains. Relict aeolian landforms would include sand sheets and longitudinal dunes, which nowadays are mostly stabilized by psammophile plant species. The presence of blowouts on these areas is evidence of current erosive processes in the dunefield. Five vegetation communities dominate the area.

Location and main vegetation communities of Dunefields: VC1. Grassland of Sporobolus rigens and Aristida spegazzinii, VC2. Subshrub steppe of Hyalis argentea, VC3. Shrub-grass steppe of Brachyclados megalanthus, Mulinum spinosum and Nassella tenuis, VC4. Grass-shrub steppe of Nassella tenuis and Mulinum spinosum. VC5. Shrub-grass steppe of Mulinum spinosum and Hyalis argentea

4.4.1 Vegetation Communities of Stabilized Aeolian Field and Active Dunefields

-

Dwarf shrub steppe of H. argentea ( VC1, Fig. 6 )

Vegetation cover is about 90%; the dominant plant is H. argentea forming big dense patches. Other grass species associated are P. urvilleanum, P. lanuginosa and S. rigens.

-

Grassland of S. rigens and Aristida spegazzinii ( VC2, Fig. 6 )

This grassland has around 75% of vegetation cover. S. rigens and A. spegazzinii account for up to 60–70% of cover and occur along with P. urvilleanum, P. lanuginosa, N. tenuis and P. napostaense. Maihueniopsis darwinii and Marrubium vulgare occurs on degraded areas.

-

Shrub - grass steppe of B. megalanthus, M. spinosum and N. tenuis ( VC3, Fig. 6 )

This community is dominated by the shrub species B. megalanthus and M. spinosum, with N. tenuis (perennial grass) dominating the herbaceous stratum. The vegetation cover is about 65%.

-

Shrub - grass steppe of M. spinosum and H. argentea ( VC4, Fig. 6 )

This community is dominated by the subshrubs species M. spinosum and H. argentea, with herbaceous secondary species such as S. rigens, P. urvilleanum, P. lanuginosa and N. tenuis. Some clumps of B. divaricata are found. Vegetation cover in this community is about 65%.

-

Grass - shrub steppe of N. tenuis and M. spinosum ( VC5, Fig. 6 )

This community (with around 70% plant cover) is dominated by the grass species N. tenuis and the shrub M. spinosum. Grasses such as S. rigens, P. urvilleanum and P. lanuginosa are codominant species.

5 Perspectives and Future Work

This chapter provides a synthesis of the state of knowledge on the vegetation of Península Valdés and identifies priority sites for conservation programs. Future work should be aimed to intensify studies on the vegetation dynamics of these priority sites and also to recognize new sites which could be sensitive to degradation due to human activities.

References

Adam P (1990) Saltmarsh ecology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Adam P (2002) Saltmarshes in a time of change. Environ Conserv 29:39–61

Ares JO, Beeskow AM, Bertiller MB, Rostagno CM, Irisarri MP, Anchorena J, Defossé GE, Merino CA (1990) Structural and dynamic characteristics of overgrazed grasslands of northern Patagonia. In: Breymeyer A (ed) Managed grasslands. Regional studies. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 149–175

Ares JO, del Valle HF, Bisigato AJ (2003) Detection of process-related changes in plant patterns at extended spatial scales during early dryland desertification. Glob Change Biol 9:1643–1659

Barros V, Rivero M (1982) Mapas de probabilidad de precipitación de la Provincia del Chubut. Monografía 54. Centro Nacional Patagónico, Puerto Madryn, 12 p

Bertiller MB, Beeskow AM, Irisarri MP (1981) Caracteres fisonómicos y florísticos de la vegetación del Chubut. 2. La Península Valdés y el Istmo Ameghino. SECyT, CONICET. CENPAT. Contribución Nº 41, 20p

Bertiller MB, Beeskow AM, Coronato F (1991) Seasonal environmental and plant phenology in arid Patagonia (Argentina). J Arid Environ 21:1–11

Bertiller MB, Ares JO, Bisigato AJ (2002) Multiscale indicators of land degradation in the Patagonian Monte, Argentina. Environ Manage 30:704–715

Bertiller MB et al (2006) Leaf strategies and soil N across a regional humidity gradient in Patagonia. Oecologia 148:612–624

Blanco PD et al (2008) Grazing impacts in vegetated dune fields: predictions from spatial pattern analysis. Rangeland Ecol Manage 61:194–203

Bortolus A (2006) The austral cordgrass Spartina densiflora Brong.: its taxonomy, biogeography and natural history. J Biogeogr 33:158–168

Bortolus A (2010) Marismas Patagónicas: las últimas de Sudamérica. Ciencia Hoy 19:10–15

Bortolus A et al (2009) A characterization of Patagonian salt marshes. Wetlands 29:772–780

Burgi MV et al (2012) Response of guanacos to changes in land management in Península Valdés, Argentine Patagonia. Conservation implications. Oryx 46:99–105

Cabrera AL (1976) Regiones Fitogeográficas Argentinas. In: Kugler WF (ed) Enciclopedia Argentina de Agricultura y Jardinería. Buenos Aires, pp 1–85

Campanella MV, Bertiller MB (2008) Plant phenology, leaf traits, and leaf litterfall of contrasting life forms in arid Patagonian Monte, Argentina. J Veg Sci 19:75–85

Castellanos A, Pérez Moreau R (1944) Los tipos de vegetacio´n de la República Argentina. Monografías del Instituto de Estudios Geográficos de Tucumán 4:1–154

Chartier M, Rostagno CM, Pazos GE (2011) Effects of soil degradation on infiltration rates in grazed semiarid rangelands of northeastern Patagonia, Argentina. J Arid Environ 75:656–661

Cheli GH (2009) Efectos del disturbio por pastoreo ovino sobre la comunidad de artrópodos epígeos en Península Valdés (Chubut, Argentina). Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Bariloche

Cipriotti PA, Aguiar MR (2005) Effects of grazing on patch structure in a semi-arid two-phase vegetation mosaic. J Veg Sci 16:57–66

Codesido MA et al (2005) Relevamiento ambiental de la “Reserva de Vida Silvestre San Pablo de Valdés”. Caracterización ecológica y evaluación de su condición como unidad de conservación y manejo. General technical report N-1. Programa “Refugios de Vida Silvestre”, Sistema de Relevamientos Ecológicos Rápidos. Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Correa MN (1969) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte II. Typhaceae a Orchidaceae (excepto Gramineae). Colección Científi ca de INTA. Buenos Aires, 219 pp

Correa MN (1971) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII Parte VII. Compositae. Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires, 451 pp

Correa MN (1978) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte III. Gramineae. Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires, 563 pp

Correa MN (1984a) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte IV a. Dicotyledones Dialipétalas (Salicaceae a Cruciferae). Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires, 556 p

Correa MN (1984b) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte IV b. Dicotyledones Dialipétalas (Droseraceae a Leguminosae). Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires, 309 p

Correa MN (1988) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte V. Dicotyledones Dialipétalas (Oxalidaceae a Cornaceae). Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires, 381 p

Correa MN (1998) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte I. Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires

Correa MN (1999) Flora Patagónica. Tomo VIII. Parte VI Flora Dicotyledones Gamopétalas (Ericaceae a Calyceraceae). Colección Científica de INTA. Buenos Aires

Elissalde NO, Miravalles H (1983) Evaluación de los campos de pastoreo de Península Valdés. 70, Centro Nacional Patagónico (CONICET), Puerto Madryn, Argentina

Frenguelli J (1940) Rasgos principales de la Fitogeografía argentina. Revista del Museo de La Plata (nueva serie). Botánica 3:65–181

Golluscio RA, Sala OE (1993) Plant functional types and ecological strategies in Patagonian forbs. J Veg Sci 4:839–846

Hauman L (1920) Ganadería y Geobotánica en la Argentina. Revista del Centro de Estudios Agronómicos y Veterinarios (Buenos Aires) 102:45–65

Hauman L (1926) Etude phytogéographique de la Patagonie. Bull Soc R Bot Belg 58:105–180

Hauman L (1931) Esquisse phytogéographique de l’Argentine subtropicale et de ses relations avec la Geobotanique sudaméricaine. Bull Soc R Bot Belg 64: 20–64

Hauman L (1947) Provincia del Monte. In: Hauman L, Burkart A, Parodi LR, Cabrera AL (eds) La Vegetación de la Argentina, Geografía de la República Argentina. Sociedad Argentina de Estudios Geográficos, GAEA, Buenos Aires, pp 208–249

Holmberg EL (1898) La flora de la República Argentina. Segundo Censo de la República Argentina 1:385–474

Idaszkin YL, Bortolus A (2011) Does low temperature prevent Spartina alterniflora from expanding toward the austral-most salt marshes? Plant Ecol 212:553–561

Idaszkin YL, Bortolus A, Bouza PJ (2011) Ecological processes shaping Central Patagonian salt marsh landscapes. Austral Ecol 36:59–67

Kühn F (1922) Fundamentos de Fisiografía Argentina. Biblioteca del Oficial, Buenos Aires

Kühn F (1930) Geografía de la Argentina. Ed. Labor, Buenos Aires

Laycock WA (1995) New perspectives on ecological condition of rangelands: can state-and-transition or other models better define condition and diversity? In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on plant genetic resources, desertification, and sustainability, INTA-EEA Rio Gallegos, Argentina, pp 140–164

León RJC et al (1998) Grandes unidades de vegetacio´ n de la Patagonia extraandina. Ecol Austral 8:125–144

Lorentz P (1876) Cuadro de la Vegetación de la República Argentina. In: Napp R (ed) La República Argentina. Buenos Aires, pp 77–136

Marino A, Rodríguez MV, Pazos GE (2016) Resource-defense polygyny and self-limitation of population density in free-ranging guanacos. Behav Ecol 27:757–765

Mitsch WJ, Gosselink JG (2000) Wetlands. Wiley

Morello J (1958) La Provincia Fitogeográfica del Monte. Opera Lilloana 2:5–115

Mueller-Dombois D, Ellenberg H (1974) Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. Wiley, New York, 547 pp

Nabte MJ et al (2013) Range management affects native ungulate populations in Península Valdés, a World Natural Heritage. PLoS ONE 8(2):e55655

Parodi LR (1934) Las plantas indígenas no alimenticias cultivadas en la Argentina. Rev Argent Agron 1:165–212

Parodi LR (1945) Las regiones fitogeográficas argentinas y sus relaciones con la industria forestal. Plants and Plant Science in Latin America, pp 127–132

Parodi LR (1951) Las regiones fitogeográficas argentinas y sus relaciones con la industria forestal. Rev Uruguaya Geogr 2:89–100

Pazos GE, Bertiller MB (2008) Spatial patterns of the germinable soil seed bank of coexisting perennial-grass species in grazed shrublands of the Patagonian Monte. Plant Ecol 198:111–120

Roig FA, Martínez Carretero E (1998). La vegetación Puneña en la Provincia de Mendoza, Argentina. Phytoecoenologia 28:565–608

Sala OE et al (1989) Resource partitioning between shrubs and grasses in the Patagonian steppe. Oecologia 81:501–505

Soriano A (1950) La vegetación del Chubut. Rev Argent Agron 17:30–36

Soriano A (1956) Los distritos florísticos de la Provincia Patagónica. Serie Fitogeográfica, RIA. Tomo X. Nº 4. INTA

Weinstein MP, Kreeger DA (eds) (2000) Concepts and controversies in tidal marsh ecology. Kluwer Academic Publishers

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Project of Ecology and Regional Development of Arid and Semiarid Regions (OEA-CONICET-INTA) and to the Centro Nacional Patagónico (CENPAT-CONICET) for supporting field research for the description of the Vegetation Units and to the Comisión Nacional de Actividades Espaciales (CONAE) from Argentina that supplied the satellite images. We also thank Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina and landowners for granting the access to San Pablo de Valdés and the adjacent ranches, respectively. GEP acknowledges Victoria Rodríguez and Andrea Marino for important input in the San Pablo de Valdés work. GEP was partially supported by PIP 11220120100369CO. Research permissions were granted by Secretaría de Turismo y Áreas Naturales Protegidas and Dirección de Fauna y Flora Silvestre de Chubut. We also thank G. Bernardelo and Marta Collantes for their helpful comments in the revision of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Floristic List

Appendix: Floristic List

Family | Species and authors |

|---|---|

Ephedraceae | Ephedra ochreata Miers |

Juncaginaceae | Triglochin concinna Burtt Davy |

Poaceae | Amelichloa ambigua (Speg.) Arriaga and Barkworth |

Aristida spegazzinii Arechav. | |

Avena sativa L. | |

Bromus catharticus Vahl | |

Bromus unioloides Humboldt, Bonpland et Kunth | |

Distichlis scoparia (Kunth) Arechav. | |

Distichlis spicata L. | |

Eremium erianthum (Phil.) Seberg and Lindle-Laursen | |

Hordeum comosum J. Presl | |

Hordeum euclaston Steud. | |

Hordeum murinum L. | |

Jarava neaei (Nees ex Steud.) Peñalillo | |

Koeleria mendocinensis (Hauman) C.E. Calderón and Nicora | |

Nassella longiglumis (Phil.) Barkworth | |

Nassella tenuis (Phil.) Barkworth | |

Panicum urvilleanum Kunth | |

Pappostipa chysophylla (E. Desv.) Romasch. | |

Pappostipa humilis (Cav.) Romasch. | |

Pappostipa speciosa (Trin. and Rupr.) Romasch. | |

Piptochaetium napostaense (Speg.) Hack. | |

Poa lanuginosa Poir. | |

Poa ligularis Nees ex Steud. | |

Polipogon monspeliensis (L.) Desf. | |

Schismus barbatus (L.) Thell. | |

Spartina alterniflora Loisel | |

Spartina densiflora Brongn. | |

Sporobolus rigens (Trin.) E. Desv. | |

Vulpia myuros (L.) C.C. Gmel. megalura Phil. | |

Amaryllidaceae | Rhodophiala mendocina (Phil.) Ravenna |

Oleaceae | Menodora robusta (Benth.) A. Gray |

Schoepfiaceae | Arjona tuberosa Cav. |

Polygonaceae | Polygonum brasiliense K. Koch |

Chenopodiaceae | Atriplex lampa (Moq.) D. Dietrich |

Atriplex sagittifolia Speg. | |

Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin and Clements | |

Sarcocornia perennis (Mill.) A.J. Scott. | |

Suaeda argentinensis A. Soriano | |

Suaeda divaricata Moq. | |

Nictaginaceae | Bougainvillea spinosa (Cav.) Heimerl |

Aizoaceae | Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. |

Caryophyllaceae | Cardionema ramosissima (Weinm.) A. Nelson and J.F. Macbr. |

Cerastium arvense L. | |

Cerastium glomeratum Thuill. | |

Cerastium junceum Möschl | |

Heniaria cinerea DC. | |

Paronychia chilensis DC. | |

Capparaceae | Capparis atamisquea Kuntze |

Rosaceae | Tetraglochin caespitosum Phil. |

Tetraglochin ameghinoi (Speg.) Speg. | |

Fabaceae | Adesmia candida Hook. f. |

Adesmia af. acuta Burkart | |

Anarthrophyllum rigidum (Gillies ex Hook. and Arn.) Hieron. | |

Hoffmannseggia trifoliata Cav. | |

Prosopidastrum globosum (Gillies ex Hook. and Arn.) Burkart | |

Prosopis alpataco Phil. | |

Prosopis denudans Benth. | |

Vicia pampicola Burkart burkartii Giangualani | |

Geraniaceae | Erodium cicutarium (L.) L’Hér. ex Aiton |

Zygophyllaceae | Larrea divaricata Cav. |

Larrea nitida Cav. | |

Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia portulacoides L. |

Euphorbia serpens Kunth | |

Anacardiaceae | Schinus johnstonii F.A. Barkley |

Rhamnaceae | Condalia microphylla Cav. |

Discaria americana Gilles and Hook. | |

Malvaceae | Malvela leprosa (Ortega) Krapov. |

Frankeniaceae | Frankenia patagonica Speg. |

Frankenia pulverulenta L. | |

Loasaceae | Loasa bergii Hieron. |

Cactaceae | Maihuenia patagonica (Phil.) Britton and Rose |

Maihueniopsis darwinii (Hensl.) Ritter | |

Onagraceae | Camissonia dentata (Cav.) Reiche |

Oenothera versicolor Lehm | |

Oenothera stricta Ledeb. ex Link altissima W. Dietr. | |

Apiaceae | Bowlesia incana Ruiz and Pav. |

Daucus pusillus Michx. | |

Eryngium chubutense Neger ex Dusén | |

Mulinum spinosum (Cav.) Pers. | |

Plumbaginaceae | Limonium brasiliense (Boiss.) Kuntze |

Apocyanceae | Phillibertia candolleana (Hook. and Arn.) Goyder |

Convolvulaceae | Dichondra microcalyx (Haller f.) Fabris |

Polemoniaceae | Gilia crassifolia Benth. |

Boraginaceae | Amsinckia calycina (Moris) Chater |

Lappula redowskii (Hornem.) Greene | |

Pectocarya linearis (Ruiz and Pav.) D.C. | |

Verbenaceae | Acantholippia seriphioides (A Gray) Moldenke |

Glandularia aurantiaca (Speg.)Botta aurantiaca | |

Mulguraea ligustrina (Lag.) N. O’Leary and P. Peralta var. lorentzii (Niederl. ex Hieron.) N. O’Leary and P. Peralta | |

Lamiaceae | Marrubium vulgare L. |

Solanaceae | Lycium ameghinoi Speg. |

Lycium chilense Miers ex Bertero | |

Lycium gilliesianum Miers | |

Lycium tenuispinosum Miers | |

Plantaginaceae | Plantago myosuros Lam. |

Plantago patagonica Jacq. | |

Rubiaceae | Galium richardianum (Gilles ex Hook. and Arn.) Endl.ex Walp |

Calyceraceae | Boopis anthemoides Juss. |

Asteraceae | Baccharis crispa Spreng. |

Baccharis darwinii Hook. et Arn. | |

Baccharis divaricata Hauman | |

Baccharis gilliesii A. Gray | |

Baccharis melanopotamica Speg. | |

Baccharis spartioides (Hook. et Arn. Ex DC.) J. Remy | |

Baccharis tenella Hook. et Arn. | |

Baccharis triangularis Hauman | |

Brachyclados megalanthus Speg. | |

Chuquiraga aurea Skottsb. | |

Chuquiraga avellanedae Lorentz | |

Chuquiraga erinacea D.Don ssp. erinacea | |

Chuquiraga erinacea D.Don ssp. hystrix(Don) C. Ezcurra | |

Cyclolepis genistoides D.Don | |

Gamochaeta chamissonis (DC.) Cabrera | |

Grindelia chiloensis (Cornel.) Cabrera | |

Gutierrezia solbrigii Cabrera | |

Hyalis argentea D. Don ex Hook. and Arn. var. latisquama Cabrera | |

Hypochaeris radicata L. | |

Hysterionica jasionoides Willd. | |

Nassauvia fuegiana (Speg.)Cabrera | |

Nassauvia ulicina (Hook. f.) Macloskie | |

Perezia recurvata (Vahl) Less.ssp. recurvata | |

Noticastrum sericeum (Less.) Less. ex Phil. | |

Senecio chrysocomoides Hook. et Arn. | |

Senecio filaginoides DC. | |

Sonchus asper (L.) Hill. |

Glossary

- Adaptation

-

The process of adjustment of an individual organism to environmental stress

- Ecotone

-

Transitional zone between adjacent plant communities or biomes

- Floristic composition

-

A list of plant species of a given area, habitat, or association

- Floristic element

-

In phytogeography, a convenient term for any group of plants sharing a common feature of importance

- Halophytic

-

Plant tolerating saline conditions

- Life form

-

The characteristic structural traits of a plant species

- Patchy

-

Contagious distribution

- Perennial

-

Plants that persist for several years with a growth period each year

- Physiognomic

-

Appearance of a plant community or vegetation

- Phytogeographical Provinces

-

Geographical divisions characterized by floristic composition

- Stratum

-

Horizontal layer of vegetation

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bertiller, M.B., Beeskow, A.M., Blanco, P.D., Idaszkin, Y.L., Pazos, G.E., Hardtke, L. (2017). Vegetation of Península Valdés: Priority Sites for Conservation. In: Bouza, P., Bilmes, A. (eds) Late Cenozoic of Península Valdés, Patagonia, Argentina. Springer Earth System Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48508-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48508-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-48507-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-48508-9

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)