Abstract

A large body of research on social competence or social skills exists in psychology, educational sciences and human resource management. In professional contexts, social competencies are mostly seen as general abilities, independent of specific workplace requirements. But in the case of vocational education and training, it is necessary to define social competence as a personal capacity which also allows acting in accordance with learning and workplace requirements. The issue of specificity versus generality of social competence still needs to be clarified. A related question pertains to the dimensionality of social competence, be it specifically related to a particular domain or relevant across domains. This has obvious methodological implications for the measurement of social competence as well as for training programmes. This chapter starts out by a discussion of different approaches to define social competencies and their implications for the problems of generality and dimensionality of social competence related to vocational and professional domains. Subsequently, measurement issues will be debated including the different methodological underpinnings for measuring social competence. The state of the art of modelling domains and competencies in these fields is then discussed, distinguishing between, among others, sales and services and social and health-care occupations. Research findings as to the structure, background, training and effects of social competence in vocational and professional domains will be critically reviewed. Finally, perspectives for future research will be identified.

The original version of this chapter was revised. An erratum to this chapter can be found at DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_51

An erratum to this chapter can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_51

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Social competence is conceptualised differently across disciplines and even within disciplines, e.g. communication , psychology and sociolinguistics (cf. Antos and Ventola 2008), but also included in applied sciences such as education, social work, medicine , marketing and human-computer interaction.

In psychology, social competence is defined as a personal trait with different facets such as cooperation, assertiveness, empathy, trust, respect for other people and tolerance , conscientiousness, self-control and emotional intelligence . From a pedagogical perspective, aspects like social and intercultural learning, the ability to adjust to different social situations in learning, training and working contexts as well as the development of social competence over the life span are of interest. In workplace settings, social competence plays an important role as a prerequisite for good individual performance and for the effectiveness of companies and organisations. Concepts of social competence at the workplace are often associated with the notion of socially responsible behaviour independent of particular situations and requirements (e.g. Goleman 1995).

Summing this up, a large body of research on social competence or social skills exists in psychology and education, where the construct is often tied to the idea of traits , to social behaviour in different situations and to personal development (e.g. Allemand et al. 2014).

It is also to be noted that in social competence research, there is a number of different definitions of the concept of competence. Correspondingly, a variety of operationalisations has been suggested. Following Weinert (2001, 62) competencies are ‘… necessary prerequisites available to an individual or a group of individuals for successfully meeting complex demands’. In addition to cognitive abilities , Weinert (ibid.) identifies motivational, moral and volitional components of competence. Based on this multidimensional concept of competence, we accept the perspective of cognitive psychology , including personal traits , capabilities, knowledge and skills in this construct. At the same time, we recognise the legitimacy of behavioural aspects when focusing on the adjustment to and interactions in different situations. In accordance with the approach of Argyle et al. (1985), we understand social competencies as relational properties. In particular, this aspect is relevant with respect to the distinction between – and possibly the interaction of – general, cross-occupational social competencies and such social skills which are specific to a particular vocation or occupation.

Correspondingly , Kanning (2009a) distinguishes three major views of social competence in psychology: clinical (e.g. Hinsch and Pfingsten 2002), developmental (e.g. Vaughn et al. 2000) and organisational psychology (e.g. Greif 1987) . Clinical psychology views social competence as the ability to articulate personal interests or pursue individual goals and plans and does not take the role of interaction partners as subjects into account. The second perspective in developmental psychology is focused on the extent to which individuals adapt to their environments (e.g. The Consortium on the School-based Promotion of Social Competence 1996; DuBois and Felner 1996) . A third group of research aims at integrating both positions and emphasises the necessity to negotiate interests between the partners and groups involved in social interaction (Rose-Krasnor 1997). Both in older and in recent research social competence is seen as a person’s ability to analyse thoughts, feelings and behaviours of his-/herself and others and to select and implement the emotional, cognitive and behavioural resources which are suitable to deal with specific personal and social situations (e.g. Pinto et al. 2012; Gresham and Elliot 1990; Ford 1995).

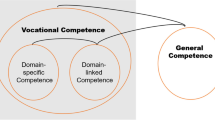

From the perspective of vocational and professional education, only the last one of these positions seems appropriate. In this context, to act socially competent requires behaviours in accordance with learning and workplace requirements as derived from an organisational, vocational or professional perspective (e.g. Bailly and Léné 2014; cf. also Wang and Netemeyer 2002). Hence, when conceptualising social competence for vocational and professional education and training as well as for workplace requirements, a central question pertains to the dimensionality of social competence, whether it is specifically related to a particular domain or relevant across domains. Three main questions arise: (1) Which abilities , knowledge and skills constitute socially acceptable behaviour in varying professional and vocational contexts? (2) How are these abilities , knowledge and skills instantiated in different situations within a given context? (3) Which factors determine the emergence of these traits in the training and education leading to the different occupations and professions?

2 Conceptualising ‘Social Competence’: Generic vs. Domain Specific

Following Kanning (2002), social competence can be defined as a comprehensive potential in terms of knowledge, abilities and skills contributing to socially competent behaviour. Socially competent behaviour pertains to such behaviour that contributes to goal attainment in specific situations and secures social acceptance. It is usually conceived as the manifestation of different constituent traits as well as motivation, attitudes , value orientations, etc. In order not to confound these with behaviour induced by specific situational conditions, social competencies need to be diagnosed and generalised across a range of situations . Kanning (2002) therefore advocates a distinction between generic and domain-specific social competencies.

Social competence is typically understood as a relational construct, describing how individuals behave within the context of interpersonal and group relationships (Schoon 2009). Different social competencies are required and valued in different contexts (Argyle et al. 1985). Thus, social competence comprises positive aspects of interpersonal , intercultural , social and civic relationships (Schoon 2009). As Bailly and Léné (2014) argue, however, social competence only becomes relevant when significant autonomy exists in the workplace (similarly Kanning 2005; Wang and Netemeyer 2002) . Drawing on examples of frontline workers in the service industry, retailing, hotel and restaurant business, these authors point out that the role of employees in direct contact with customers has expanded with regard to bargaining contracts and solving customers’ problems. This has in turn increased the significance of social competence and other ‘soft skills ’ for task performance in these domains. Workers are constrained by growing responsibilities for results, i.e. the requirement to internalise organisational norms as ‘a self-disciplinary form of control ’ (Bailly and Léné 2014, 13). It follows from this that beyond the overarching shifts in the organisation of work, changing specific norms play a role in what constitutes socially acceptable behaviour and how it can be conceptualised. Moreover, these norms are likely to be explicitly expressed as vocational and professional expectations and standards, if these exist (Billet 2006).

Contrary to these tenets, social competence is usually conceptualised, even in professional contexts, as a set of rather general abilities , very much independent of specific situational workplace requirements (e.g. Hochwarter et al. 2004; Holling et al. 2007; Frey and Balzer 2007; Jennings and Greenberg 2009; Ramo et al. 2009; Kinman and Grant 2011; Kanning et al. 2012) . No consensus exists, however, as to the degree of their transferability from one workplace to the next. Thus, the issue of specificity versus generality of social competence still needs to be clarified (cf. Heller 2002). It may very well be the case that the relationship between specificity and generality varies across vocational fields. In occupations and professions which are dominated by social interaction, specific knowledge may tend to assume an auxiliary role as a necessary but insufficient condition for successful performance. In professions where social interactions are less prominent, the converse may be true: here, specific knowledge may be primarily significant as opposed to more general social traits . The possibility of such variation needs to be taken into account if an operationalisation of social competence is proposed.

The present article explores how social competence can be conceptualised adequately and how it is applicable to the notion of vocational and professional success. In pursuit of this goal, the issue of specificity versus generality is examined − as an example − across two specific areas of occupations and professions with a high share of social activity: (a) sales and services and (b) social and health care.

3 Social Competence as a Generic Construct

In this section, we will start by discussing problems surrounding the definition of social competence as a generic construct. While in the subsequent section we elaborate on the role social competence as a generic concept plays in vocational and professional learning, the third subsection debates the conditions under which social competence can be seen as a prerequisite to workplace performance and professional success. The fourth subsection refers to problems with a generic construct in the context of vocational and professional education.

3.1 Defining the Construct

According to Dirks et al. (2012, 2751), there is a growing consensus that the construct of social competence ‘reflects effectiveness in interpersonal relationships’ (cf. Rose-Krasnor 1997). Variations in interpersonal effectiveness may stem from individual differences, behavioural variety and situations – namely, ‘the interpersonal circumstances in which behaviour is embedded’ (Dirks et al. 2012, 2751) – and may also depend on the person who is evaluating the behaviour.

Following this perspective, social competence may be seen as a constituent trait such as social intelligence or emotional competence. But as a comprehensive potential underlying socially competent behaviour in terms of knowledge, abilities and skills, it is broader in scope than either of these.

A large number of authors have set up a list of individual trait variables deemed integral to social competence and corresponding training approaches (e.g. Segrin and Givertz 2003). These variables cover a great spectrum, e.g. empathy and social sensitivity (Adams 1983), facial expressiveness (Segrin and Givertz 2003), perspective taking assertiveness to emotional stability and even a sense of humour (Dirks et al. 2012). Conducting a second-order factor analysis across these constructs , Kanning (2009b) identified empirically the following principal components: social orientation, offensiveness, self-control and self-awareness (see Fig. 48.1).

Social competence inventory (According to Kanning 2009b)

Behavioural perspectives additionally take outcomes and criteria of goal attainment into account, for example, with regard to peer popularity or peer relations (Dirks et al. 2012; cf. Adams 1983; Ladd 2005) . Situational factors, ranging from features of classes of situations to singular situational circumstances, will influence behavioural-evaluative criteria (Dirks et al. 2012). However, there are still many open questions. The judgemental aspect of ‘who evaluates’ has largely been neglected (Dirks et al. 2010, 2012). As Dirks et al. (2012) point out, studies evaluating youth social competence have either relied on the extent of agreement between different judges – peers, parents and teachers – about an adolescent’s competence or simply assumed consensus on what constitutes competent behaviour. They call attention to the fact that ‘[such] investigations leave unanswered the question of the extent to which important people in the social environment concur about the competence of specific behaviours’ (Dirks et al. 2012, 2752). In addition to the aspects observed by Dirks et al. (2012), Kanning (2002) considers a temporal reference as an important element of conceptualising social competence, since competent behaviour may mean different things at varying points in time, a notion which complements, for example , Bailly and Léné’s (2014) or Bloom’s (2009) understanding.

3.2 Social Competence as a Prerequisite and an Outcome of Vocational and Professional Learning

Social and emotional competencies are seen as important predictors of success in schools (e.g. Blumberg et al. 2008, 177) and in professional and vocational learning, as well as in modern workplaces (e.g. Robles 2012). In this chapter, some light is shed on social competence in the context of vocational and professional learning and learning achievement. The promotion of social competencies is an important independent goal in vocational education and training, but it is also an important prerequisite for vocational and professional learning. In the view of Wenger (2003) , “knowing is an act of participation in complex ‘social learning systems’” (76), “a matter of displaying competencies defined in social communities” (77). As seen from this perspective, learning is understood as a social process, an interplay between social competence and personal experience. Thus, socially competent behaviour is not only defined by social environments including organisations but also by the respective historical context. While it shapes personal experience, social competence, defined as “what it takes to act and be recognized as a competent member” (78), is also shaped by an individual’s experience.

Under the perspective of learning, social competencies relate to very different abilities . A number of models have been proposed which show certain commonalities with the facets of existing generalised models of social competence while also stressing certain peculiarities in their acquisition. According to a meta-analysis of Calderella and Merell (1997), five distinct dimensions are constitutive for the acquisition and development of social competencies:

-

1.

The ability to establish positive relationships within the respective learning/peer group, an ability listed as ‘social orientation’ in Kanning’s model

-

2.

The ability to cooperate, such as the acceptance of social rules (whose components are often subordinate to and distributed across several facets of generic competency models) and the constructive handling of critique (compliance)

-

3.

Abilities of self-management, which Kanning subsumes under the construct ‘self-control’

-

4.

Academic competencies , which include, above all, teacher-student relationships focused on learning, that entail the ability to follow instructions or to ask teachers and other learners

-

5.

‘Assertiveness’, which implies the ability to initiate and maintain a dialogue or to maintain or terminate close social relationships such as friendships

Kolb and Hanley-Maxwell (2003) have proposed a slightly different model. Beyond ‘peer and group interaction’, ‘self-management’ and ‘assertion’, they emphasise the significance of ‘communication ’ and ‘problem-solving/decision-making’. The perfection of an appropriate language is seen as an important prerequisite of the development of social competence, given that language is the principal means of initiating and maintaining social relationships. Conversely, language deficits can inhibit the development of social competencies, e.g. by inviting rejection by the peer group. Correlations between linguistic and social abilities and skills have been observed not only in early childhood settings but also among adolescents, e.g. in a study of immigrant youth in Germany (Jerusalem 1992). These findings underscore the fact that language deficits inhibit the integration and opportunities for social participation, while language proficiency functions as a resource in establishing social relationships and skills. Based on this insight, in-school and in-firm support for the learner’s acquisition of communicative abilities and skills contributes significantly to the emergence of social competencies.

Whereas the acquisition of social competencies in schools usually – with the exception of speech-impaired children – occurs through peer interaction, i.e. informally and without any pedagogical concept, vocational education and training present a clearly different scenario. Here, social learning, also labelled as collaborative learning, group learning, service learning, peer learning or tutoring, is assumed to have a positive impact on the development of substantive competencies. Also, social learning is more frequently ascribed to learning at the workplace where team activities are typical, with one trainee learning from her or his peer. It is implicitly assumed that the inherent potential of social experience contributes to the emergence of social competency (Dubs 1995, 296). This is most likely to occur when the systematic, pedagogically structured nurture of specific facets of social competency is enhanced by the training of the intended substantive competencies.

It is to be noted, however, that, in the context of ‘dual’ vocational education and training and firm-based training, learning processes of social learning are not restricted to vocational schools but are also assigned to the firms, i.e. the workplaces. The latter ‘occurs in the demand of action, effectiveness and productivity’ and ‘is most often rather incidental and spontaneous’ (Thång 2009, 428/429). It is a place for formal and informal learning, where learning by experience and incidence on the one hand and organised, intentional learning on the other come together. In addition to substantive learning, the workplace is also assumed to have a special function in conveying social competencies. Here, in contrast to school settings, social competencies are acquired through contacts with different groups of persons from various levels in the organisational hierarchy and through contacts with external clients and partners of the firm. Consequently, the acquisition of social competence is also connected to affective organisational commitment and organisational citizenship (cf. Abraham 2005, 263/264).

3.3 Social Competence as a Prerequisite for Workplace Performance and Professional Success

In occupational and professional contexts, social competence is sometimes referred to ‘soft skills ’ or ‘emotional intelligence ’ and denotes traits such as flexibility and abilities to work in a team, to motivate colleagues and clients and to show effective leadership.

Robles (2012, 454) lists an impressive volume of research on the significance of social competencies at the workplace. Van Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004) have conducted a meta-analysis of 69 separate studies, resulting in robust and substantial relationships between the construct of ‘emotional intelligence ’ and workplace performance. Insofar as the constructs of ‘emotional intelligence ’ and ‘social competence’ clearly overlap, show many similarities and have interdependent components (cf. Kang et al. 2005), these research results may be also indicative of the relevance of social competence for vocational and professional success.

In recent years, a growing awareness of social competencies in the area of personnel recruitment and personnel development has been observed. More than ever, social competencies appear to function as the key to individual success as well as a necessary condition for the success of an enterprise as a whole (Crisand 2002). In occupations and professions, which are characterised by social and communicative acting, like professions in the area of social and health care or occupations in the service and sales sector, social competencies have become an immanent part of vocational or professional competence . But they are also increasingly required in technical occupations and professions, for skilled manual jobs and for skilled work in production. A growing part of work orders and tasks is solved cooperatively. An increasing complexity of tasks requires multi-professional teamwork with specialists from various occupational and professional fields and from different status groups. Within large organisations, there are many project-based, short- and long-term relationships and formal and informal contacts that build up networks in order to share practices and goals. In other words, work results are obviously highly dependent on social relations and on the social competencies of persons working in these networks and groups.

In this context, it is helpful to distinguish between social competencies which refer directly to the provision of products and services, i.e. external contacts with clients and customers and those which are related to the internal process of the organisation. Whereas the former are likely to be akin to specific requirements of the job, the latter will have a high degree of transferability across occupations and professions.

3.4 Problems with a Generic Construct in the Context of Vocational and Professional Education

It has been mentioned above that Kanning (2002) distinguishes between generic and domain-specific social competencies. The assumption underlying his concept of general social competencies is that some social competencies are relevant independent of a particular social setting. In this view, other social competencies are relevant only in specific social settings. Kanning (2002) concludes that general social competencies are predominant in personnel selection. As opposed to this, domain-specific social competencies are of interest for personnel development, since they require context-specific training opportunities. An alternative would amount to the assumption that social competencies are always specific to a situation. Kanning (2002) rejects this notion, however, postulating a consensus according to which social behaviour rests on the interplay of situational and individualistic variables. While socially competent behaviour is invariably deemed to be specifically situational with respect to time, space, personal interests, local norms and other factors, some underlying traits may transcend situations and even domains.

Yet the existence of such a core of general social competencies which would be applicable across domains can be contested and remains to be questioned (Wittmann 2001a, 2003). Bloom (2009, 13) suggests, for example, the possession of ‘abstract moral values suitable to one’s life context and historic time’ as part of an operational definition of adolescents’ psychosocial competence (cf. Wilson and Sabee 2003 for a discussion on how ethics may enter into conceptions of ‘communicative competence’). However , Beck et al. (2001, 1999) show evidence of moral regression specific to the area of external relationships of an insurance company subsequent to vocational education and training in the insurance industry. This may indicate that perspective taking is more important in private life or in some vocations than in others. Moreover, it is possible and perhaps even likely that the relationship between specificity and generality varies across vocational fields or between cultures within the same occupational field (Weeks et al. 2006). It seems important, therefore, to examine research on domain-specific variations of required social behaviour as well as social competencies associated with these requirements.

4 Social Competence as a Domain-Specific Construct

In this section, we will first discuss fundamental considerations of conceptualising social competence as a domain-specific construct, such as the interrelation of factual knowledge and social competence. In the following subsections, we elaborate on the issues suggested here, based on the state of empirical research for the selected areas of vocational and professional education with high shares of social interaction, which is sales and services as well as social and health care. The selection is also driven by the fact that these areas have attracted a considerable body of research.

4.1 Fundamental Considerations of Conceptualising Social Competence as a Domain-Specific Construct

Apart from the sales and services sector, social competencies in social and health care have been of particular interest in the literature (e.g. Argyle 1994; Street 2003). But research on social competence has been conducted in other vocational or professional areas as well, e.g. police work (Holling et al. 2007). More generally, it can be assumed that domain specificity is particularly strong in occupations and professions focused on working with other people, i.e. dialogical-interactive work (Hacker 2009).

From the sociological viewpoint laid out by Goffman (1959) in his writings on the ‘presentation of self in everyday life’, institutional interaction can be compared to a staged theatre performance. All public behaviour is conceptualised as leaving an impression upon spectators which they in turn interpret as a self-expression. Performance is meant to influence viewers. Professionals act using a standardised repertoire of expression – including clothing, physical appearance, ways of speaking and personal expression – labelled as ‘personal facade’. It is accompanied by the stage setting which includes the setup of the room and is meant to invoke certain definitions of the situation by the interaction partner. The surface, or ‘front stage’, of such staged performance is strictly separated from what is conceptualised as ‘backstage’, where professional actors interact out of sight of the viewer and suppressed facts come to light or are being dealt with.

Following Goffman’s (1959) concept of staged interaction in institutionalised contexts, occupations and professions requiring social interaction can arguably be differentiated according to the way in which they relate backstage to front stage (Wittmann 2001a, b), both in terms of vocationally or professionally informed social perception and vocationally or professionally informed social expression (Nerdinger 1998).

An often neglected aspect lies in the role of the relationship between factual knowledge and social competence in the vocational and professional field. One possibility to address the issue of specificity is to assume that in occupations and professions that are dominated by social interaction, requirements of socially competent behaviour tend to be more specific to the demands of the audience, whereas factual knowledge is reduced to a rather auxiliary role – a necessary but insufficient condition for successful performance. Another possibility is that the factual knowledge and the recognition of social demands become intertwined to an extent where they cannot meaningfully be separated. Hence, the relationship between factual knowledge, social requirements and social competence needs to be clarified.

Another possibility is that social requirements and respective competencies across professions and occupations vary primarily with regard to the emotional underpinning (Gieseke 2007). As has been pointed out, e.g. by Zapf (2002), such ‘emotion work’ is comprised of automatic emotion regulation, namely, the so-called surface acting. This, on the one hand, consists of the visible display of expressions in contradiction to inner feelings, as opposed to ‘deep acting’. On the other hand, it refers to the kind of behaviour where emotion is genuinely invoked through the inner search of thoughts, images and memories. Zapf’s argument rests on Goffman’s (1959) idea of drawing analogies between everyday social interaction and theatrical role playing (cf. Hochschild 2012). Emotion work occurs when face-to-face or voice-to-voice interactions between professionals and clients take place. Emotions are displayed in an effort to influence other people’s emotion, attitudes or behaviour, and they are framed by certain rules. They also affect backstage behaviour (Zapf 2002). With this argument , Zapf (2002) follows the work of Ekman (1973), who emphasises the existence of ‘display rules’ for facial expression. It appears that this concept is highly compatible with the notion of social competence specific to different occupations and professions. The following is intended to explore this assumption.

4.2 Sales and Services

In sales and services, customer contact is acted out on what Goffman (1959) conceptualises as front stage, with the purpose of influencing customer impressions both at the level of individual interaction and at the management level. As opposed to this, company goals and strategies as well as production details and trade conditions are decided upon backstage, either entirely or in the form of rough frameworks. Contracts are also processed in areas customers hardly get to access (Damiani 1991; Wittmann 2001a, b).

Following Goffman (1959), Wittmann (2001a, b) argues that the inhibition of customers’ perceptions is a constitutive element for services and sales work in highly competitive markets. From the viewpoint of the customers, respective practices differ depending on the products and services provided. In banking, for example, some products may require expert explanation or simply risky investment on the part of the customers. While consumers trust in the company’s problem-solving activities is vital for the perceived quality of sales and services, this in turn serves the latter’s economic purposes of maximising company income (Brünner 1994). Thus, in the case of sales and services staff, expertise lies predominantly in the social domain. Knowledge about the supplied products may be necessary, but its display will be subject to and framed by strategies of impression management and influence. Hence, situations may arise where too much product knowledge by salespersons is deemed detrimental, in particular when this leads to empathising with customers in ways that prevent sales achievements.

In this regard, the concept of role becomes quite obviously important. The psychology of sales and services emphasises role conflicts and their perceptions by the staff involved as well as strategies to cope with these conflicts (Damiani 1991; Nerdinger 1998, 2001). Possible conflicts include the two-bosses-dilemma, resulting from contradictions between employer and customer expectations (cf. Katz and Kahn 1978 on the work roles of staff at the boundary of organisations; also Rastetter 2008), inconsistent goals of long-term customer retention vs. raising the short-term sales volume or conflicts between customer expectations and the self-concept and the values of the salesperson (Weeks et al. 2006). Conducting qualitative analyses of spoken text, linguists have investigated the variance between institutional contexts and viable avenues for solving such conflicts by means of communication and social interaction (e.g. Brünner 1994; Antos and Ventola 2008). Guiding the interaction process, influencing customer needs and managing conflict, but also managing relations preventively, and controlling self-expression become vital strategies to cope with these demands (Damiani 1991; Brünner 1994; Nerdinger 2001).

According to Homburg et al. (2012, 217) who summarise a broad range of empirical support for their theory, ‘enduring sales success has less to do with special sales techniques, but rather essentially depends on three aspects’ which these authors conceptualise as ‘personality ’, namely, ‘social competence’ and ‘professional competence ’. These personality traits refer to the extent that a salesperson consistently likes him- or herself and others and displays sociability, optimism, self-esteem and empathy. Whereas social competence refers to social interaction and includes general aspects of verbal and nonverbal communication with regard to both perception and expression, as well as components of situational adaptations, such as the possession of customer typologies, professional competence pertains to (hierarchically organised) sales-related knowledge, such as sales process knowledge, but also products, business or market knowledge. It also refers to knowledge about customers’ environments, situations and needs, both in abstract and detailed forms, which contribute to the salespersons’ long-term success. A growing body of research supports this approach; see the literature discussed by Tschöpe (2013), who builds upon Hacker’s (2009) theory on ‘interaction work’ and suggests that access to interaction partners’ mental models is required to act adequately in the service industry. This includes general heuristics as well as situated reasoning for important or new situations (cf. also Nerdinger 2001). Successful salespeople use better customer typologies, i.e. better integrated knowledge structures of customer traits and negotiating strategies (Sujan et al. 1988). In addition to possessing richer descriptions and more distinctive categories, they classify customers according to their needs rather than physical characteristics (Sharma et al. 2000). However, short-term sales in an initial sales encounter are unaffected by differentiated typologies, according to a study by Evans et al. (2000). More successful salespeople appear to have acquired the ability to qualify or categorise customers according to both client types and associated product and selling requirements as demonstrated by their ability to provide information in accordance with customer needs (Román and Iacobucci 2010). According to a meta-analysis conducted by Franke and Park (2006), adaptive selling behaviour, i.e. the adaptation of the selling behaviour depending on situational information, contributes positively to sales performance as measured by self-ratings, manager ratings and objective measures of performance . Homburg et al. (2009a, b, 64) introduce the concept of ‘customer need knowledge’ (CNK) to describe ‘the extent to which a frontline employee can accurately identify a given customer’s hierarchy of needs’. According to these authors, customer need knowledge mediates the effects of both customer orientation and cognitive empathy exerted by salespersons on customer satisfaction and customer willingness to pay. Findings by Homburg et al. (2011), for example, based on a cross-industrial survey, suggest that customer orientation with regard to sales of individualised products success is optimal in highly competitive markets and for firms which pursue a premium price strategy. While customer orientation is consistently positively related to customer attitudes , its relationship to sales success seems to be curvilinear.

To sum up, the current state of research indicates the importance of certain general abilities , i.e. traits , but also the need for situational adaptation; the success of which is mediated by both abstract and specific knowledge. Such knowledge can be both social knowledge, as in the case of customer knowledge, and relate to product, organisational or market specifics. This model may be less successful, however, in areas where short-term sales success is the organisational or branch-specific norm.

As Nerdinger (2001) argues, emotion work also plays a significant, and possibly specific, role for competent social interaction in the sales and services industry. In particular, low status sales and services tend to be subject to impolite customer behaviour. As a result, emotional work on the part of the sales and services staff is required which includes the necessity to comply with job- and organisation-specific rules of expression (Rafaeli and Sutton 1987). Possible strategies in the sales and services industry are either characterised by surface acting or situational reinterpretation, such as reinterpreting unfriendly behaviour – rightly or wrongly – as customer anxiety (Nerdinger 2001) . However, as Sutton and Rafaeli (1988) argue, such ‘display rules’ may also vary in response to specific situations. In their quantitative study of a chain of urban convenience stores, the display of positive emotions was negatively linked to the sales figures. According to their qualitative research findings – obtained by these authors in case studies of four stores – busy and high-paced store settings required the rather neutral display of emotions, whereas slow settings tended to demand the display of positive emotions. This interpretation appeared to be compatible with the quantitative evidence .

While the requirement to display emotions seems to be common to sales and services work on the one hand and social and health care on the other, situations which require the pretence of emotion against personal convictions, which may even result in ethical conflicts, are apparently specific to sales and services work – although they may become more common with tendencies to apply business sector models to health-care institutions (Senghaas-Knobloch 2008; Rastetter 2008) . When ‘acting’ is required irrespective of actual feelings, ‘emotional dissonance’ occurs, a term describing deviations of genuinely felt emotions from emotional expressions required by organisational or professional norms (Zapf 2002). In the view of Hacker (2006), it is this aspect that separates what he calls ‘interaction work’ from other types of work. Since their underlying purpose is the selling of products or services, customer relationships can be ended at almost any given time by the disclosure of such inconsistencies. Similarly, ethical behaviour, which implies authentic feelings, may often reduce the likelihood of successful performance (Gieseke 2011), particularly in areas where short-term sales are the norm, e.g. in second-hand car retailing (e.g. Brünner 1994). For sales personnel, this requires adaptations not only in terms of behaviour but also in terms of applied reasoning.

4.3 Social and Health Care

As in the sales and services industry, an important aspect of social competence in social and health-care work is the separation of emotional experience and emotional expression (Gieseke 2007). Unlike sales and services, however, genuinely felt emotion is often considered part of the social and professional identity of care workers (Briner 1999; Zapf 2002) , and contrary to sales and service contexts, there is also some likelihood that authentic emotional expression will be tolerated in backstage vocational and professional working environments (Gieseke 2007).

Some further differences exist between social and health-care work on the one hand and work in the sales and services industry on the other. While to influence clients’ emotions can be considered as a prerequisite of successfully carrying out work requirements in both cases, in care work contributions to emotional change on the part of the client is not just a means to selling products and services but is also an end in itself – to the extent that it can be even more important than physical healing, as is particularly the cases of care for the elderly, care for victims of fatal diseases or psychotherapy (Hacker 2006). Similarly, patient activation and participation are goals deemed central to care work (Street 2003, 915). Here, it is important to note that contrary to Zapf’s (2002) assumptions, this should not be seen in analogy to service work oriented at making customers feel good, like hostess work, where the ultimate goal is to influence customers to spend money in an enterprise. In the case of care work, the requirement to emotionally influence clients also makes it necessary to adequately assess their feelings. Zapf (2002) argues that ‘[to] be able to manage the client’s emotions, the accurate perception of their emotions is an important prerequisite’ (240). He further emphasises the empirically found correlation between ‘sensitivity requirements’ and ‘emotion expression requirements’.

An important difference between both areas of service work should be noted. Whereas emotional expressions in the helping professions are likely to be constrained by professional requirements – which are in turn transmitted through vocational and professional education – such behaviour in sales and services is only guided by organisational demands (Rastetter 2008). Moreover, one may suspect that care work requires a greater array of emotional expression than other kinds of work (Zapf 2002) . This assumption would require empirical scrutiny, however. As Wildemeersch et al. (2000) note for guidance and counselling, the professional challenge in this area consists of balancing standardisation , regulated by output demands, predetermined procedures, a tendency to reduce complexity and individualisation strategies, regulated by the demands of an authentic encounter and the readiness to deal with situational complexity and interaction partners’ individuality.

A particular aspect of social and health care refers to the fact that these professions also require abstract thinking and a substantial amount of knowledge about age- and disease-related restrictions and impairments in client communication (e.g. Korpijaakko-Huuhka and Klippi 2008; Gülich and Lindemann 2010). Other than in sales and services, where information and communication deficits predominantly concern products or services to be sold, in the case of care work with specific groups of clients or patients, substantial professional knowledge is required with regard to the interaction process itself, such as interaction with children or with clients who suffer from dementia (Wittmann et al. 2014) or hearing loss (Deppermann 2012). This demonstrates that in addition to emotional perception and expression, factual knowledge forms an integral part of social interaction in these occupations and professions.

In a comparison of different occupations and professions, an important issue refers to the extent to which the specific behaviour is scripted in the form of cognitive schemata, as is typical for routine behaviour (Zapf 2002) . According to empirical findings of Morris and Feldman (1997), such ‘scripting ’ is likely to occur when occupational or vocational requirements are such that episodes of emotional display remain short, as in the case of hospital nursing. In the context of prolonged interaction in care work, however, the concept of ‘emotional dissonance’ in the care profession gains importance. As Zapf (2002) points out, emotional dissonance can be understood as an external requirement which varies considerably even within care work, for example, with regard to feelings of disgust between child nursing and old age care. In the medical profession, professional feeling rules often require moderate emotional display, while at the same time ‘internal emotional neutrality’ is necessary to exercise one’s work. It can be argued that the ambivalence of maintaining emotional detachment while displaying a certain level of emotional engagement in client interactions is a particular requirement of sociologically defined professions.

To sum up, the relationship between factual knowledge and socially interactive behaviour seems much more intertwined for care work than for sales and services. Client knowledge, both abstract and concrete, is an indispensable requirement for carrying out the task in many areas of care work, with individualised communication being the norm for competent social action.

5 Measurement of Social Competencies

As already mentioned, the occupational and professional sector is characterised by a clear lack of empirical research – despite substantial initiatives in this direction.

The evaluation of competencies, in particular for purposes of staff recruitment, feedback concerning work or the establishment of cooperative structures in the organisation of work, but also for the targeted enhancement of specific facets of social competence, requires a theory-based concept of the property to be evaluated. The current deficit in terms of accepted rules for measuring social competencies results from challenges and difficulties in defining the construct. As has been emphasised above, social competencies develop predominantly in interactive processes, depending on individual and situational characteristics. They represent latent dispositions which can only be captured through their manifestations in concrete situation. Hence, their measurement presumes that personal and situational aspects and their interactions have to be taken into account (cf. Maag-Merki 2005, 366).

A further difficulty stems from the fact that the interpretation of the obtained values normally is not related to a maximum as the desired state but to a range of possible values where the optimum is defined as a corollary of normative premises.

The currently available instruments for measuring social competencies are based upon different methodological approaches. Standardised inventories and self-ratings are frequently chosen, although the spectrum of covered properties is often rather narrow and specific. Self-ratings or self-reports of behaviour are usually applied in personnel selection and in the area of personnel development, in the context of performance feedback and in school-related and further education-related learning and assessment contexts. There are, indeed, quite a number of different psychometric scales available to measure specific dimensions such as assertiveness or cognitive and affective aspects of empathy, self-control, self-efficacy, locus of control and prosocial behaviour (see Schoon 2009, 5). However, the use of self-ratings and self-reports for the measurement of social competencies is rather controversial. In particular, concerns have been raised with respect to their construct and prognostic validity, their reliability and the likelihood of compliance effects (cf. Schoon 2009, 6; Maag-Merki 2005, 366) . External observation of individual behaviour or assessment-centred techniques (Schuler 2007) may well generate valid and valuable data pertaining to relevant occupational and professional situations, but drawing heavily on time resources.

Situational judgement tests may be interpreted as a compromise between self-ratings and external observations, although they in turn present problems as a consequence of their inherent multidimensionality with subsequent problems in terms of the quality of the measurement. Further problems derive from the fact that few of the existing instruments take the specificity of the investigated interactions into account. Focusing on learning strategies , Friedrich and Mandl (1992, 18) have named this the ‘dilemma of scope versus precision’, which seems to hold for the measurement of social competencies as well and which is exacerbated by unsettled issues concerning the functionality of domain specific as opposed to overarching/generic competencies . More recent approaches attempt to capture social competencies by way of computer-based measurement techniques. Here, stimuli consist of standardised occupational situations, e.g. by the use of video vignettes, followed by instructions to interpret the situation and to suggest a concrete course of action (cf. Wittmann et al. 2014). This computer-/video-based technique also permits to search answers to questions concerning the domain specificity of social competencies, as some of the situations presented as stimuli are bound to a narrow occupational context while others refer rather generally to cross-occupational contexts.

There is no point in denying, however, that a great deal of development still needs to be done, if objective, reliable and valid research instruments are to be obtained, in order to arrive at defensible psychometric models of social competence. Multi-method strategies may help to facilitate pragmatically useful, theoretically grounded process analyses.

6 Conclusions

The theoretical basis laid out in this chapter suggests the existence of a general, broadly transferable core of social competence pertaining to a wide range of vocational and professional social interaction. At the surface level, it entails the ability to adequately perceive and express messages both through verbal and nonverbal channels and to adapt to situations. Specific differences between the vocations and professions here investigated depend on the following factors:

-

1.

The goals of social interaction.

-

2.

The extent to which professional norms play a role and have to be balanced against organisational norms and rules.

-

3.

The nature and relevance of factual knowledge about social interaction and the extent to which it is intertwined with what can be meaningfully described as social competence.

-

4.

The degree in which the expression of emotion is expected or even required.

-

5.

The existence and impact of vocation or occupation-specific scripts for institutionalised contexts where short-term interaction is the rule.

In dealing competently with emotion, a balance in handling the ‘emotional dissonance’ between external expectations and internal states and processes is an integral and essential part of social competence in vocations and professions, for which interaction with external clients or customers is constitutive. Yet the abovementioned deliberations also lead to the conclusion that in some respect the differences examined between the vocational and professional areas are quite substantial. The long-term vs. short-term nature of the communicative relationship specifically, the extent to which it is individualised and the fact that economisation has – at least as of now – not yet fully dominated the area of care work may be relevant distinguishing factors.

The differential development of social competence specific to the vocations or professions discussed here remains to be further clarified by empirical investigations. Another aspect which is in particular a need of future studies is the relevance of psychomotor skills and cognitive abilities for occupational and professional performance (Kanning 2002; Greene 2003) . In particular, it appears promising to examine the open questions pertaining to the relationships between domain-specific and overarching competencies.

Apart from requirements for empirical research and improvements in measurement, the chapter warrants thoughts on policy- and curriculum-oriented questions. While, as demonstrated, a substantial body of research and empirical evidence exists in the field of social competence in vocational and professional education, it seems questionable that the differentiations and findings proposed in this chapter have made their way into policy considerations and vocational education curricula. Other than subject matter competencies, it seems likely that social competence is considered less accessible to sound theory and empirical research and that educational practice in schooling is guided either by generic ideas of social competence. But besides knowledge, specifically in vocational education, there may be another complication: features immanent to social interaction may prevent systematic theory-based treatment in vocational schools. There is some likelihood that, where, like in some areas of sales and services, ethical conflicts are prevalent but spaces for authentic emotional expression are lacking in the workplace environment, there will be little interest or tolerance for putting all features of domain-specific social interaction out in the open.

References

Abraham, R. (2005). Emotional competence in the workplace: A review and synthesis. In R. Schulze & R. Roberts (Eds.), Emotional intelligence. An international handbook (pp. 255–270). Cambridge/Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Adams, G. R. (1983). Social competence during adolescence. Social sensitivity, locus of control. Empathy, and peer popularity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 12(3), 203–211.

Allemand, M., Steiger, A. E., & Fend, H. A. (2014). Empathy development in adolescence predicts social competencies in adulthood. Journal of Personality. 10.111/jopy.12098.

Antos, G., & Ventola, E. (Eds.) (2008). Handbook of interpersonal communication. In cooperation with T. Weber. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Argyle, M. (1994). The psychology of interpersonal behaviour (5th ed.). London: Penguin.

Argyle, M., Henderson, M., & Furnham, A. (1985). The rules of social relationships. British Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 125–139.

Bailly, F., & Léné, A. (2014). What makes a good worker? Richard Edwards is still relevant. Review of Radical Political Economics, 46(1), 1–17. doi:10.1177/0486613414532766.

Beck, K., Heinrichs, K., Minnameier, G., & Parche-Kawik, K. (1999). Homogeneity of moral judgement? Apprentices solving business conflicts. Journal of Moral Education. doi:10.1080/030572499102990.

Beck, K., Bienengräber, T., Mitulla, C., & Parche-Kawik, K. (2001). Progression, stagnation, regression – Zur Entwicklung der moralischen Urteilskompetenz während der kaufmännischen Berufsausbildung. In K. Beck & V. Krumm (Eds.), Lehren und Lernen in der beruflichen Erstausbildung (pp. 139–161). Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Billet, S. (2006). Work, change and workers. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bloom, M. (2009). Social competency. In T. P. Gullotta, M. Bloom, C. F. Gullotta, & J. C. Messina (Eds.), A blueprint for promoting academic and social competence in after-school programs (pp. 1–19). New York: Springer.

Blumberg, S., Carle, A. C., O’ Connor, K. S., Moore, K. A., & Lippman, L. H. (2008, June). Social competence: Development of an indicator for children and adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 1(2), 176–197, doi:10.1007/sl2187-007-9007-x.

Briner, R. B. (1999). The neglect and importance of emotion at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(3), 323–346.

Brünner, G. (1994). Würden Sie von diesem Mann einen Gebrauchtwagen kaufen? Interaktive Anforderungen und Selbstdarstellung in Verkaufsgesprächen. In G. Brünner & G. Graefen (Eds.), Texte und Diskurse. Methoden und Ergebnisse der Funktionalen Pragmatik (pp. 328–350). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Calderella, P., & Merell, K. W. (1997). Common dimensions of social skills of children and adolescents: A taxonomy of positive behaviors. School Psychology Review, 26(2), 264–278.

Crisand, E. (2002). Soziale Kompetenz als persönlicher Erfolgsfaktor. Heidelberg: Sauer-Verlag.

Damiani, E. (1991). Qualität im Bankgeschäft. Theoretische Vorstellungen und ihre Umsetzung in der Praxis. Dissertation an der Universität Augsburg, Augsburg.

Deppermann, A. (2012). Negotiating hearing problems in doctor-patient interaction: Practices and problems of accomplishing shared reality. In M. Egbert & A. Deppermann (Eds.), Hearing aids communication. Integrating social interaction, audiology and user centered design to improve communication with hearing loss and hearing technologies (pp. 90–103). Mannheim: Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

Dirks, M. A., Treat, T. A., & Weersing, V. R. (2010). The judge specificity of evaluations of youth social behavior: The case of peer provocation. Social Development, 19(4), 736–757. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00559.x.

Dirks, M. A., Treat, T. A., & Weersing, V. R. (2012). Social competence. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 2751–2759). New York: Springer.

DuBois, D. L., & Felner, R. D. (1996). The quadripartite model of social competence. In M. A. Reinecke, F. M. Dattillio, & A. Freman (Eds.), Cognitive therapy with children and adolescents (pp. 124–152). New York: Guilford.

Dubs, R. (1995). Lehrerverhalten. Ein Beitrag zur Interaktion von Lehrenden und Lernende im Unterricht. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

Ekman, P. (1973). Cross-cultural studies of facial expression: A century of research in review. New York: Academic.

Evans, K. R., Kleine, R. E., Landry, T. D., & Crosby, L. A. (2000). How first impressions of a customer impact effectiveness in an initial sales encounter. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(4), 512–526.

Ford, M. (1995). Intelligence and personality in social behavior. In D. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence (pp. 125–140). New York: Plenum Press.

Franke, G. R., & Park, J. E. (2006). Salesperson adaptive selling behavior and customer orientation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 693–702.

Frey, A., & Balzer, L. (2007). Beurteilungsbogen zu sozialen und methodischen Kompetenzen – smk72. In J. Erpenbeck, J., & H. Rosenstiel (Eds.), Handbuch Kompetenzmessung. Erkennen, verstehen und bewerten von Kompetenzen in der betrieblichen, pädagogischen und psychologischen Praxis (pp. 348–660). 2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl. Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel.

Friedrich, H. F., & Mandl, H. (Eds.). (1992). Lern- und Denkstrategien. Analyse und Intervention. Göttingen/Toronto/Zürich: Hogrefe.

Furnham, A. (2008). Personality and intelligence at work: Exploring and explaining individual differences at work. East Sussex/New York: Routledge.

Gieseke, W. (2007). Lebenslanges Lernen und Emotionen. Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Gieseke, W. (2011). Emotionale Kompetenzen: Erweiterte Anforderungen in Dienstleistungsberufen. Grenzen und Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten in Lernprozessen. Reflexionen und Perspektiven der Weiterbildungsforschung. In D. Holzer, B. Schröttner, & A. Sprung (Eds.), Reflexionen und Perspektiven der Weiterbildungsforschung (pp. 27–38). Münster: Waxmann.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Greene, J. O. (2003). Models of adult communication skill acquisition. Practice and the course of performance improvement. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 51–91). New York: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Greif, S. (1987). Soziale Kompetenzen. In D. Frey & S. Greif (Eds.), Sozialpsychologie. Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen (pp. 312–320). München: Psychologie Verlags Union.

Gresham, F., & Elliot, S. (1990). Social skills rating system. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Gülich, E., & Lindemann, K. (2010). Communicating emotion in the doctor-patient interaction. A multidimensional single-case analysis. In D. Barth-Weingarten, E. Reber, & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in interaction (pp. 269–294). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Hacker, W. (2006). Interaktive/dialogische Erwerbsarbeit – zehn Thesen zum Umgang mit einem hilfreichen Konzept. In F. Böhle & J. Glaser (Eds.), Arbeit in der Interaktion – Interaktion als Arbeit. Arbeitsorganisation und Interaktionsarbeit in der Dienstleistung (pp. 17–24). Wiesbaden: VS.

Hacker, W. (2009). Arbeitsgegenstand Mensch: Psychologie dialogisch-interaktiver Erwerbsarbeit. Lengerich: Pabst.

Heller, K. A. (2002). Intelligenz: allgemein oder domain-spezifisch? Kommentar zum Artikel “Emotionale Intelligenz – ein irreführender und unnötiger Begriff”von Heinz Schuler. Diskussionsforum. Zeitschrift für Personalpsychologie, 1(4), 179–180.

Hinsch, R., & Pfingsten, U. (2002). Gruppentraining sozialer Kompetenzen (GSK). 4., überarb. Aufl. Weinheim: Beltz.

Hochschild, A. R. (2012). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Updated with a new preface. Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

Hochwarter, W. A., Kiewitz, K., Gundlach, M. J., & Stoner, S. (2004). The impact of vocational and social efficacy on job performance and career satisfaction. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10(4), 27–40. doi:10.1177/107179190401000303.

Holling, H., Kanning, U. P., & Hofer, S. (2007). Das Personalauswahlverfahren “Soziale Kompetenz“(SOKO) der Bayerischen Polizei. In J. Erpenbeck, & H. Rosenstiel (Eds.), Handbuch Kompetenzmessung. Erkennen, verstehen und bewerten von Kompetenzen in der betrieblichen, pädagogischen und psychologischen Praxis, 2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl (pp. 97–109). Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel.

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., & Bornemann, T. (2009). Implementing the marketing concept at the employee–customer interface: The role of customer need knowledge. Journal of Marketing, 73(4), 64–81. doi:10.1509/jmkg.73.4.64.

Homburg, C., Müller, M., & Klarmann, M. (2011). When should the customer really be king? On the optimum level of salesperson customer orientation in sales encounters. Journal of Marketing, 75(2), 55–74.

Homburg, C., Schäfer, H., & Schneider, J. (2012). Sales excellence. Systematic sales management. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Jennings, P., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom. Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. doi:10.3102/0034654308325693.

Jerusalem, M. (1992). Akkulturationsstress und psychosoziale Befindlichkeit jugendlicher Ausländer. Report Psychologie, 17, 16–25.

Kang, S.-M., Day, J. D., & Meara, N. M. (2005). Social and emotional intelligence: Starting a Conversation about their similarities and differences. In R. Schulze & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), Emotional intelligence. An international handbook (pp. 91–105). Cambridge/Göttingen: Hofgrefe & Huber Publishers.

Kanning, U. (2002). Soziale Kompetenz – Definition, Strukturen, Prozesse. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 210(4), 154–163. doi:10.1026//0044-3409.210.4.154.

Kanning, U. (2005). Soziale Kompetenzen. Entstehung, Diagnose, Förderung. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Kanning, U. (2009a). Diagnostik sozialer Kompetenzen (2nd ed.). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Kanning, U. (2009b). Inventar sozialer Kompetenzen. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Kanning, U., Böttcher, W., & Herrmann, C. (2012). Measuring social competencies in the teaching profession – development of a self-assessment procedure. Journal for Educational Research Online, 4(1), 141–154.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organizations (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Kinman, G., & Grant, L. (2011). Exploring stress resilience in trainee social workers. The role of emotional and social competencies. British Journal of Social Work, 41(2), 261–275. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcq088.

Kolb, S. M., & Hanley-Maxwell, C. (2003). Critical social skills for adolescents with high incidence disabilities: Parental perspectives. Exceptional Children, 69(2), 163–179.

Korpijaakko-Huuhka, A.-M., & Klippi, A. (2008). Language and discourse skills of elderly people. In G. Antos, E. Ventola, & T. Weber (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (pp. 481–505). In cooperation with T. Weber. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Ladd, G. W. (2005). Children’s peer relations and social competence. A century of progress. New Haven/London: Yale University Press.

Maag-Merki, K. (2005). Überfachliche Kompetenzen in der Berufsbildung. In F. Rauner (Ed.), Handbuch Berufsbildungsforschung (pp. 361–368). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Morris, J. A., & Feldman, D. C. (1997). Managing emotions in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Issues, 9(3), 257–274.

Nerdinger, F. W. (1998). Psychologische Aspekte der Tätigkeit im Dienstleistungsbereich. In M. Bruhn & H. Meffert (Eds.), Handbuch Dienstleistungsmanagement (pp. 195–212). Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Nerdinger, F. W. (2001). Psychologie des persönlichen Verkaufs. München/Wien: Oldenbourg.

Pinto, J. C., do Ceu Taveira, M., Candeias, A., Araujoa, A., & Mota, A. I. (2012). Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.409.

Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R. I. (1987). Expression of emotion as part of the work role. Academy of Management Review, 12(1), 23–37.

Ramo, L. G., Saris, W. E., & Boyatzis, R. E. (2009). The impact of social and emotional competencies on effectiveness of spanish executives. Journal of Management Development, 28(9), 771–793. doi:10.1108/02621710910987656.

Rastetter, D. (2008). Zum Lächeln verpflichtet. Emotionsarbeit im Dienstleistungsbereich. Frankfurt: Campus.

Robles, M. M. (2012). Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 453–465.

Román, S., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Antecedents and consequences of adaptive selling confidence and behavior: A dyadic analysis of salespeople. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38, 363–382.

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1997). The nature of social competence. A theoretical review. Social Development, 6(1), 111–135. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00097.x.

Schoon, I. (2009). Measuring social competencies. Working Paper No. 58. Berlin: Council for Social and Economic Data (RatWSD). http://www.ratswd.de/download/RatSWD_WP_2009/RatSWD_WP_58.pdf

Schuler, H. (2007). Assessment Center zur Potenzialanalyse. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Segrin, C., & Givertz. (2003). Methods of social skills training and development. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 135–176). New York: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Senghaas-Knobloch, E. (2008). Care-Arbeit und das Ethos fürsorglicher Praxis unter neuen Marktbedingungen am Beispiel der Pflegepraxis. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 18(2), 221–243.

Sharma, A., Levy, M., & Kumar, A. (2000). Knowledge structures and retail sales performance: An empirical examination. Journal of Retailing, 76(1), 53–69.

Street, R. S. (2003). Interpersonal communication skills in health care contexts. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 909–933). New York: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Sujan, H., Sujan, M., & Bettman, J. R. (1988). Knowledge structure differences between more effective and less effective salespeople. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(1), 81–86.

Sutton, R. I., & Rafaeli, A. (1988). Untangling the relationship between displayed emotions and organizational sales: The case of convenience stores. Academy of Management Journal, 31(3), 461–487.

Thång, P.-O. (2009). Learning in working life – Work integrated learning as a way to develop competence at work. In F. K. Oster, U. Renold, E. G. John, E. Winther, & S. Weber (Eds.), VET boost: Towards a theory of professional competencies (pp. 423–436). Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

The Consortium on the School-based Promotion of Social Competence. (1996). The school-9. In L. R. Sherrod, N. Garmezy, & M. Rutter (Eds.), Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents (pp. 268–316). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tschöpe, T. (2013). “Mentale Repräsentationen sozialer Interaktionen als Grundlage für die Messung von Sozialkompetenz” oder “Wissen und Sozialkompetenz”. Vortrag gehalten auf der Fachtagung ‘Welches Wissen ist was wert?’ Soziale Inwertsetzung von Wissensformen, Wissensarbeit und Arbeitserfahrung in der Berufsbildung. BIBB, 18.10.2013. Bonn. http://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/stabpr_veranstaltung_2013_10_17_welches_wissen_ist_was_wert_tschoepe.pdf. Accessed 16 Aug 2014.

Van Rooy, D. L., & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Emotional Intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 65, 71–95.

Vaughn, B. E., Azria, M. R., Krzysik, L., Caya, L. R., Bost, K. K., Newell, W., & Kazura, K. L. (2000). Friendship and social competence in a sample of preschool children attending head start. Developmental Psychology, 36(3), 326–338. 10.1G37//OG12-3649.36.3326.

Wang, G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). The effects of job autonomy, customer demandingness, and trait competitiveness on salesperson learning, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 217–228.

Weeks, W. A., Loe, T. W., Chonkom, L. B., Marinez, C. R., & Wakefield, K. (2006). Cognitive moral development and the impact of perceived organizational ethical climate on the search for sales force excellence. A cross-cultural study. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 26(2), 205–217.

Weinert, F. E. (2001). Concept of competence: A conceptual clarification. In D. S. Rychen & L. H. Salganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies (pp. 45–65). Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber.

Wenger, E. (2003). Communities of practice and social learning systems. In D. Nicolini, S. Gherardi, & D. Yanow (Eds.), Knowing in organizations. A practice-based approach (pp. 76–99). New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Wildemeersch, D., Jansen, T., Gieseke, W., Illeris, K., Weil, S., & Marhinho, M. (2000, June 2–4). Balancing instrumental, biographic and social competencies. Enhancing the participation of young adults in economic and social processes. In T. J. Sork, V.-L. Chapman, & R. St. Clair (Eds.), AERC 2000: An international conference. Proceedings of the annual adult education research conference (pp. 593–594). 41st, Vancouver, Canada.

Wilson, S. R., & Sabee, C. M. (2003). Explicating communicative competence as a theoretical term. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 3–50). New York: Lawrence Earlbaum.

Wittmann, E. (2001a). Kompetente Kundenkommunikation in der Bank. Frankfurt: Lang.

Wittmann, E. (2001b). Zu kundenkommunikativ kompetentem Handeln und zum Einfluß betrieblicher Ausbildungsbedingungen – Theoretische Überlegungen, empirische Befunde und Anregungen zur praktischen Bedeutsamkeit am Beispiel des Ausbildungsberufs Bankkaufmann/Bankkauffrau. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, Beiheft, 16, 104–110.

Wittmann, E. (2003). “Kommunikative Kompetenz” in der persönlichen Kundenberatung. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 99, 417–434.

Wittmann, E., Weyland, U., Nauerth, A., Döring, O., Rechenbach, S., Simon, J., & Worofka, I. (2014). Kompetenzerfassung in der Pflege älterer Menschen – Theoretische und domänenspezifische Anforderungen der Aufgabenmodellierung. In U. Fasshauer, S. Seeber, & J. Seifried (Eds.), Jahrbuch Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik 2014 (pp. 53–66). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Zapf, D. (2002). Emotion work and psychological well-being. A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 237–268.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Seeber, S., Wittmann, E. (2017). Social Competence Research: A Review. In: Mulder, M. (eds) Competence-based Vocational and Professional Education. Technical and Vocational Education and Training: Issues, Concerns and Prospects, vol 23. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_48

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_48

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-41711-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-41713-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)