Abstract

This chapter focuses on the contribution of strengths of character and mindfulness to the sense of meaning in life across central life domains, such as work, education, and family. Our conceptualization of character strengths is based on the universal VIA Classification of 24 character strengths, which are hierarchically organized across six broader virtue categories (Peterson and Seligman, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004). We discuss empirical findings regarding various aspects of character strengths: strengths endorsement, strengths deployment, general strengths, and specific strengths. We then discuss mindfulness meditation and related practices; beginning with core concepts, followed by research findings around mindfulness practices and manualized programs. Next, we turn to a review of what is known about the integration of character strengths and mindfulness, followed by an examination of meaning, the integration of meaning and character strengths, and the integration of meaning and mindfulness, from conceptual and scientific frameworks. This culminates to an articulation of practice considerations. Here, we examine two domains: (1) targeted interventions, which reflect this research (i.e., “sources of meaning,” “strengths alignment,” and “what matters most?”), and (2) a multi-faceted character strengths program, Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP), aimed to increase the meaningful life. We conclude with suggestions for future research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The term positive psychology originated with Abraham Maslow, a humanistic psychologist, who first coined the term in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality . Maslow did not like how psychology concerned itself mostly with dysfunction and disorder, arguing that it did not have an accurate understanding of human potential. He emphasized how psychology successfully shows our negative side by revealing much about our illnesses and shortcomings, but not enough on our virtues or aspirations (Maslow, 1954). The scientific study of positive psychology emerged in the late 1990s as a call to social scientists to bring greater attention to what’s best in people, relationships, and organizations. Martin Seligman (1999) acknowledged the tremendous gains that had occurred in traditional psychology in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of mental disorders, addictions, and other problems over the preceding century. However, in comparison, only a paucity of studies had addressed happiness, positive traits, positive subjective experiences, and positive institutions. Since that time, thousands of studies have been published in the domain of positive psychology, scholarly journals have emerged (e.g., Journal of Positive Psychology), and institutions have been created to dedicate a focus to one or more aspects of this work (e.g., VIA Institute on Character). In this chapter, we will discuss some of this research and target a few of the topics that fall under this umbrella (character strengths, mindfulness, and meaning) and offer points around the integration therein.

Character Strengths

What Are Character Strengths?

Character strengths are positive human traits that influence human thoughts, feelings and behavior, providing a sense of fulfillment and meaning (Park, Peterson, & Seligman, 2004). Character strengths have different moral values than those of aptitudes, and unlike aptitudes, character strengths can be developed. According to the positive psychology literature, for a trait to be considered a character strength, most of the following criteria must be met: (1) a strength must contribute to fulfillment and to the good life; (2) a strength must be morally valued in its own right; (3) the expression of a strength does not diminish people; (4) almost every parent wants their child to have the strength; (5) there are rituals and institutions in a society that support the strength; (6) the strength is universal, valued across philosophy, religion, politics, and culture—past and present; (7) there are people who are profoundly deficient in one or more strengths; (8) the strength is measurable; (9) there are prodigies and paragons that reflect the strength in profound ways; and (10) the strength is distinct in and of itself, from other strengths and positive qualities (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2015). Following the research of 55 scientists over a number of years, 24 character strengths were found to meet these and other criteria , and to be ubiquitous across cultures. The result is what is known as the VIAFootnote 1 Classification of character strengths and virtues and is assessed using the VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA Survey). Table 1 outlines this framework. Following this groundbreaking classification system in 2004, scientists have published over 200 peer-reviewed articles using the VIA Survey measurement tool and VIA Classification (see www.viacharacter.org for a review of studies). For example, studies have empirically shown that the endorsement and application of strengths is correlated with positive individual outcomes, such as increased happiness, meaning in life, job satisfaction, and decreased depression (e.g., Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005), to name a few.

In their book, Character Strengths and Virtues (CSV) , Peterson and Seligman provided a positive alternative to the well-known and widely used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) . The CSV provided what some refer to tongue-in-cheek as the anti-DSM, but more specifically the CSV represents a common language for researchers and practitioners in psychology, and in the field of positive psychology in particular. The CSV is considered to be a cornerstone of the field. In the VIA Classification, Peterson and Seligman (2004) identified 24 character strengths from an original pool of hundreds, and classified them into six broader virtues: (1) wisdom and knowledge (includes the strengths of creativity, curiosity, judgment/critical thinking, love of learning, and perspective/wisdom); (2) courage (including bravery, honesty, perseverance, and zest); (3) humanity (including kindness, love, and social intelligence); (4) justice (including teamwork, fairness, and leadership); (5) temperance (including forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation); and (6) transcendence (including appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, and spirituality/religiousness). These six virtues are the core features traditionally valued by philosophers and religious scholars; they are universal and are likely grounded in human biology (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Peterson suggested that while the 24 strengths are the “good” in a person, their absence, opposite or excess is the “ill” in a person (Seligman, 2015). However, this theoretical proposal has not yet been tested empirically.

The Benefits of Character Strengths

One of the most interesting findings to emerge from the research is the importance of what is termed signature strengths. Signature strengths are those strengths that typically emerge highest in one’s results profile on the VIA Survey and are viewed as those strengths most core or essential to the individual’s identity. Research continues to investigate how many signature strengths individuals have. While early research suggested three to five and while the convention of many researchers is to limit individuals’ quantity to five, research from the VIA Institute finds that many people believe they have far more than five core signature strengths (Mayerson, 2013). The use of individuals’ most signature strengths of character seems to have particularly positive effects: Seligman and colleagues (2005) and Gander and colleagues (2013) have found that using one’s signature strengths (defined as the five most dominant core strengths) in new and different ways for a number of days led to significant increases in happiness and decreases in depressive symptoms. These effects were sustained at a 6-month follow-up. Similar results with signature strengths interventions have been achieved with different populations, e.g., youth (Madden, Green, & Grant, 2011), older adults (Proyer, Gander, Wellenzohn, & Ruch, 2014), people with traumatic brain injuries (Andrewes, Walker, & O’Neill, 2014), and students (Linley, Nielsen, Gillett, & Biswas-Diener, 2010). Working students who made use of at least two of their signature strengths in a new way over a 2-week period reported higher levels of harmonious passion for their work, which was also associated with an increase in their well-being (Forest et al., 2012). In a similar way, applying signature strengths at work was linked with perceiving work as a calling (Harzer & Ruch, 2012) and with positive effects on performance (Engel, Westman, & Heller, 2012).

The endorsement of character strengths has been linked with a host of positive psychological outcomes, such as life satisfaction and positive affect (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012), self-acceptance, a sense of purpose in life, environmental mastery, physical and mental health (Leontopoulou & Triliva, 2012), coping with daily stress (Brooks, 2010), and resilience to stress and trauma (Park & Peterson, 2006, 2009). Recently, Littman-Ovadia and Lavy (2015) pointed to perseverance as the character strength most highly associated with work performance and most negatively associated with counter-productive work behaviors.

Although strengths endorsement is important and beneficial, an individual’s ability to use his or her strengths is much more important in predicting job and life satisfaction (Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010). The use of character strengths seems to promote academic goal-achievement for college students, which in turn is associated with greater well-being (Linley et al., 2010). Recent evidence from a diary study has shown daily strengths deployment as a mood-repair mechanism (Lavy, Littman-Ovadia, & Bareli, 2014a).

These studies demonstrate the importance of strengths endorsement and deployment for various positive outcomes at work and in life in general. Indeed, Littman-Ovadia and Steger (2010) found that both recognition and active use of strengths in vocational activities were related to greater vocational satisfaction, greater well-being, and a more meaningful experience in work and in life.

Beyond contributing to the individual’s own well-being, character strengths also enhance the welfare of others in the individual’s social environment (Niemiec, 2013; Peterson & Seligman, 2004), specifically his or her partner. Evidence from a study of adolescent couples in a dating context provides support for this claim, indicating that certain character strengths of each partner (i.e., women’s forgiveness and men’s perseverance, social intelligence, and prudence) are associated with the other partner’s life satisfaction (Weber & Ruch, 2012). Strengths endorsement and deployment in married couples were recently found to be important for both partners ’ life satisfaction (Lavy, Littman-Ovadia, & Bareli, 2014b).

Mindfulness

Core Concepts

The literature on mindfulness consists of two distinct (albeit related) concepts. One is derived from contemplative, cultural, and philosophical traditions such as Buddhism, and involves the cultivation of a moment-to-moment, non-judgmental awareness of one’s present experience (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). This concept of mindfulness is practiced mainly through formal and informal meditation and mindful living practices (Nhat Hanh, 1979; Niemiec, 2012). The second concept of mindfulness is derived from Western scientific literature, and is defined as a mindset of openness to novelty in which the individual actively constructs categories and distinctions (Langer, 1989). More recently, scientists in the field of mindfulness gathered to conceptualize an operational definition of mindfulness in order to offer greater consistency for this construct in future studies. This group arrived at a two-part definition of mindfulness: (1) mindfulness involves the self-regulation of attention; and (2) an attitude of curiosity, openness, and acceptance (Bishop et al., 2004). This definition, which was to provide guidance for the field, is what will be most instructive for this chapter.

The practice of mindfulness derives from ancient Buddhist meditation practices from over 2500 years ago, and is described as the experience of consciously attempting to focus attention on the present moment, in a non-judgmental manner, where one attempts to not dwell on discursive, ruminating thought, putting aside past and future distractions (Shapiro, 1982). Niemiec (2014) summarized Stern’s (2004) present moment phenomenology as a brief, not necessarily verbal experience that is just long enough to capture the shortest of holistic happenings (groupings of thoughts, feelings, actions, or sensations) currently in our awareness or consciousness. Mindfulness, then, is contrasted with the habitual mind, the automatic processing that our minds are busy with on a daily basis, the activities or mind wanderings we go by without much attention or effort (Niemiec, 2014; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2013). As a “way of being,” mindfulness can be applied to any moment-to-moment experience (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). As such, mindfulness can be considered not only as a technique or an exercise, but should rather be looked at as a path to building greater awareness of the present moments in our experiences (Niemiec, 2014).

A meta-analysis conducted by Sedlmeier and colleagues (2012) sought to understand the effects of mindfulness-based meditation, examining 163 studies and their reported effects on outcomes such as anxiety, concentration, and well-being. Overall, the results indicated that mindfulness has a global positive effect, generally having a positive impact across psychological variables, although effects are stronger on negative emotional variables rather than cognitive ones.

To date, a number of mindfulness-based interventions have been developed. The most notable program is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR ) (Kabat-Zinn, 1982, 2003), an effective treatment for daily life stress and stress-related symptoms (Praissman, 2008). Other notable programs include: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT ) (Segal et al., 2013) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT ) (Linehan, 1993). Many more mindfulness-based interventions exist, with the aim of repairing physical or mental health conditions (see Cullen, 2011).

Correlates

All of these mindfulness-based interventions share the goal of alleviating problems and symptoms, and indeed, a recent meta-analysis supports that mindfulness is beneficial in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. Khoury and colleagues (2013) examined the effects of mindfulness-based interventions across 209 studies with more than 12,000 participants. It is important to note that this meta-analysis sought to better isolate the effects of mindfulness, looking at interventions such as MBCT and MBSR , and therefore excluded therapies that included mindfulness as part of another treatment, such as DBT and ACT. This meta-analysis pointed to mindfulness therapies’ potential in decreasing clinical and non-clinical levels of anxiety and depression at post-treatment, with results maintained or improved at follow-up. Mindfulness-based interventions were also shown to increase mindfulness itself (as measured in the various studies), the levels of which in-itself strongly correlated with the above-mentioned clinical outcomes, pointing to the key role mindfulness may play in the effectiveness of these therapies.

Practicing mindfulness has been shown to have positive effects across a wide range of domains in one’s everyday life. In examining mindfulness and relationships, Kowalski et al. (2014) showed that mindfulness was related to the feeling of happiness and decreased expression of pet peeves among partners. In examining mindfulness for organizational and personal well-being, Baccarani, Mascherpa, and Minozzo (2013) demonstrated that practicing mindfulness for 4 weeks increased well-being, self-control, general health and vitality, while anxiety and depression were decreased. Desrosiers, Klemanski, and Nolen-Hoeksema (2013) set out to examine the connection between the facets of mindfulness (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reacting to inner experiences [Baer et al., 2008]) and depression and anxiety, finding that all facets of mindfulness, with the exception of observing, were negatively and significantly related to depression and anxiety. Van Dam, Hobkirk, Sheppard, Aviles-Andrews, and Earleywine (2014) examined mindfulness with respect to the same five facets as above, demonstrating that mindfulness therapy lowered anxiety, depression, and perceived stress. In another example, Desrosiers, Vine, Klemanski, and Nolen-Hoeksema (2013) found that mindfulness was negatively related to depression and to anxiety, mediated by rumination and worry, respectively.

In addition, many positive associations have been found between mindfulness and flourishing-related outcomes, such as subjective well-being, positive affect, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, optimism, self-regulation, self-compassion, positive relationships, vitality, creativity, health, longevity, and a range of cognitive skills (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Brown & Kasser, 2005; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007; Carson, Carson, Gil, & Baucom, 2004; Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011).

Integration of Character Strengths and Mindfulness

Theoretically, there has been little discussed about the overall integration and mutual impact of mindfulness and character strengths. In the original VIA classification work (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), links were drawn between character strengths and Buddhist mindfulness training, not unlike the traditions of Tibetan Buddhism which has drawn close links between meditation and the strengths of compassion and wisdom (Chodron, 1997). As mentioned earlier, Bishop and colleagues (2004) defined mindfulness as involving two character strengths: self-regulation of one’s attention and curiosity to allow for an attitude of openness and acceptance. Baer and Lykins (2011) argued that mindfulness meditation can facilitate the cultivation of strengths and can increase well-being. The time one spends using character strengths correlates with the levels of mindfulness one has (Jarden et al., 2012).

For a review of research exploring the links between mindfulness and each of the particular 24 character strengths, see Niemiec (2014). By way of a couple of examples, creativity and judgment were found to correlate with mindfulness (Sugiura, 2004), and hope/optimism was increased as a result of mindfulness practice (Carson et al., 2004).

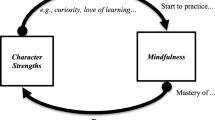

Some research has drawn from the work of Thich Nhat Hanh (1998, 2009), linking in detail how the Five Mindfulness Trainings are connected with character strength use (see Niemiec, 2012). Niemiec and colleagues (2012) voiced how these two human elements have the potential for growth and self-improvement, as well as highlighted more explicitly how a connection between mindfulness and character strengths exists. They argued that there is a potential for integrating the two practices together, to create a virtuous circle of positive impact, or, as they elude—an upward positive spiral (Fredrickson, 2001). In this way, they explained how mindfulness can help one to express character strengths in a way that is balanced and sensitive to context , and also that character strengths can bolster an individual’s mindfulness practice by overcoming typical obstacles and barriers—thus supercharging mindfulness (Niemiec, 2014). Furthermore, due to the nature of character strengths interventions (e.g., selecting a character strength to apply to a real-life situation), there is a practical foundation that enables a ready-made pathway for mindfulness, and consequently, mindful living (Niemiec, 2012).

Meaning and Purpose

Core Concepts and Research

Meaning in life is the perception of a purpose, significance or mission in life, and its role in positive human functioning was noted by Frankl (1965) long before positive psychology existed as we know it today (Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010; Steger, 2009). Since the turn of the century, meaning has been receiving much attention, and there is a growing body of research showing that finding meaning in life is indicative of well-being, good mental health, and decreased psychopathology (Vella-Brodrick, Park, & Peterson, 2009). As such, meaning is one of the higher correlating constructs (besides engagement and pleasure) with life satisfaction, and is a key player among these three pathways to a happy life (Peterson, Park, & Seligman, 2005).

Meaning can be found in any context an individual is part of, be it a religious institution or work (Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005). In assessing the components of well-being, a meaningful life has been described as one that serves a higher purpose, and provides a lasting meaning to a life that matters (Peterson et al., 2005). Proyer, Annen, Eggimann, Schneider, and Ruch (2012) argued that such a purpose can be seen in those that choose a military career—a career that is meant to serve the greater good. Their study examined the role of the three orientations to happiness in career satisfaction, with only the meaningful life playing a significant role in its prediction.

Littman-Ovadia and Steger (2010) have further demonstrated the role of meaning in life, showing its significant relationship to satisfaction in work and life, in working and volunteering groups. Satisfaction in the latter group further supports the notion of life satisfaction and well-being being derived from an activity perceived to be serving a higher purpose.

Regardless of the context, considering the significant contributions that meaning has on satisfaction in the various domains, on well-being, and happiness as a whole, individuals strive to achieve a meaningful life (Duckworth et al., 2005). When considering the amount of time spent there, it is of no surprise that constructs like meaning should be examined at the workplace (Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010). As such, it is also natural that people should strive to find work that is meaningful, “work that is both significant and positive in valence” (Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012, p. 323).

In their study comparing volunteer and paid workers, Littman-Ovadia and Steger (2010), among other variables, examined the relationship between meaning and satisfaction from life, work, and well-being. Their volunteer and working samples demonstrated a strong connection between having meaning in their volunteer activity/work and life satisfaction.

As such, meaningful work, providing one with a sense of higher purpose, is integral to the sense of calling (Steger, Pickering, Shin, & Dik, 2010). Calling is the perception one’s work has toward fulfilling one’s destiny, the opportunity to enjoy one’s work while being good at it. Seeing one’s work as a calling allows one to experience all three orientations of happiness—engagement, meaning, and pleasure—through the work place (Harzer & Ruch, 2012). To further support this notion, research conducted on calling indicates that experiencing one’s work as a calling is linked to increased work and life-related well-being (Duffy, Bott, Allan, Torrey, & Dik, 2012).

McKnight and Kashdan (2009) theorized that a purpose in life is the ultimate aim around which all aspects of one’s life, one’s behaviors and goals, are organized. In terms of the basic elements of purpose, it (1) stimulates behavioral consistency, (2) generates appetitively motivated behaviors, (3) stimulates cognitive flexibility, (4) aids in efficient resource allocation for greater productivity, and (5) stimulates higher level cognitive processing. They suggested a three-dimensional theory, such that the following three concepts can describe purpose: (1) scope—the breadth of the purpose’s influence across the various domains in life; (2) strength—the actions, thoughts, and emotions that purpose influences within its scope; and (3) awareness—the attention paid to the purpose, influenced by the scope and strengths of the purpose (e.g., if one’s purpose is broad in scope and is strong, one is very likely to be more aware of it). The aspects that allow one to organize one’s life toward one’s purpose are interrelated, and once a certain cognitive or behavioral cue is activated, the entire network is activated and is brought to one’s awareness. Organizing all the necessary cues through the purpose-centered framework lightens one’s cognitive load. When one is unaware of one’s purpose, resources necessary for its achievement are much less organized. A purpose in one domain does not mean that one cannot have a purpose in another, and it may be beneficial to have the opportunity to work toward a second purpose when the first becomes too difficult. That being said, having too many purposes may make cognitive resources difficult to allocate. Among the benefits of purpose are the organization of emotions, buffering against stress and increased resilience. Ultimately, McKnight and Kashdan (2009) suggested that purpose is influential in health and well-being.

In support of the latter point, Hill and Turiano (2014) set out to examine the effect of purpose on longevity. Longevity was examined longitudinally (14-year follow up) across different age groups, showing that purpose was significantly associated with longevity regardless of age, such that its benefits are demonstrated across the lifetime.

Integration of Character Strengths and Meaning

Peterson, Ruch, Beermann, Park, and Seligman (2007) conducted an initial study examining the relationship of character strengths and the three modes of existence according to authentic happiness orientations (Seligman, 2002)—the pleasurable, engaging, and meaningful existence. While all 24 strengths significantly accounted for some of the variance in all three orientations to happiness, the effect was the largest in the meaningful orientation. In turn, meaning was the stronger predictor of life satisfaction. Meaning was most strongly associated with the character strength of religiousness/spirituality, with the character strengths of zest, hope, and gratitude also revealing high correlations with meaning .

When examining individual strengths, zest, curiosity, gratitude, and hope emerged with the strongest associations with all three modes of existence—the pleasurable, engaging, and meaningful existence (Brdar & Kashdan, 2010). These specific strengths also showed the highest associations with the three most important human needs according to self-determination theory (SDT ; Ryan & Deci, 2001)—satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, and competence needs—as well as with life satisfaction (Brdar & Kashdan, 2010). Looking at meaning specifically, Brdar and Kashdan (2010) found that a meaningful life was significantly correlated with all 24 strengths.

The role of character strengths and meaning has also been considered at the workplace. Specifically, Littman-Ovadia and Steger (2010) examined the deployment and endorsement of character strengths in two samples of volunteers and a sample of working adults. Deploying strengths at work provided key links to meaning among both young and middle-aged volunteers, and adult working women. Among adult volunteers and paid workers, endorsing strengths was related to meaning. Together, these findings provide a model for understanding how strengths may play a role in explaining how both volunteer and paid workers find meaning.

Finally, a study conducted by Allan (2015) found not only that all 24 strengths were positively correlated with a meaningful life, but that a balance in certain strengths was also related to a meaningful life. High agreement in the pairs of kindness and honesty, love and social intelligence, and hope and gratitude were related to the experience of a meaningful life. If this harmony is important, these results indicate that for a meaningful life, it is important to develop all, rather than a few, character strengths.

In Peterson and colleagues’ study (2007), it was found that the path to life satisfaction and the strengths of religiousness/spirituality and perspective was mediated by meaning. Berthold and Ruch (2014) examined satisfaction in life in non-religious and religious people. Their results indicated that those that practice their religion score higher on the strengths of kindness, love, hope, forgiveness and spirituality, and report a more meaningful life .

Character strengths-based interventions were shown to increase happiness (meaning being a key concept in defining happiness) with lasting effects in Seligman and colleagues’ (2005) Internet-based study. In a later study, Gander, Proyer, Ruch, and Wyss (2013) replicated Seligman and colleagues’ (2005) study and demonstrated that the intervention of using a character strength in a new way had not only increased happiness, but also alleviated symptoms of depression, and its effects lasted for 6 months after the intervention. The study also showed the benefits of utilizing more specific strengths-based interventions, such as the gratitude visit, on well-being. Proyer, Ruch, and Buschor (2013) have also tested the effects of character strengths-based interventions on happiness, also operating under Seligman and colleagues’ (2005) definition of happiness. Although, instead of looking at signature strengths, Proyer and colleagues (2013) compared the effects applying strengths that are highly correlated with life satisfaction (zest, humor, curiosity, gratitude, and hope) versus those strengths that do not often correlate with life satisfaction (appreciation of beauty and excellence, creativity, kindness, and love of learning) and a group that received no strengths intervention of any sort, finding that both character-strengths groups reported increased life satisfaction and happiness.

Kerr, O’Donovan, and Pepping (2015) examined the effects of gratitude or kindness interventions in a clinical setting, where individuals were asked to list things they were grateful for or list the kind acts they had committed, respectively. Although there was an increase in satisfaction with life, the study did not find that either intervention increased meaning in life, as measured by the Purpose in Life test (rather than the Authentic Happiness Inventory , which is commonly used to assess happiness on its components, including meaning in life). It is also important to note that the study used rather small groups of roughly 16 participants in each of its three groups (kindness, gratitude, and control).

Integration of Mindfulness and Meaning

With the potential that mindfulness has for experiencing the self and surroundings, it seems natural to examine the effects that such a process could have on one’s meaning in life.

In attempting to validate a mindfulness assessment, the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ ; Baer et al., 2008), mindfulness was checked against measures of psychological symptoms, as well as measures of psychological well-being. Purpose, and within it meaning, was one of the core elements measuring psychological well-being. Mindfulness was found to be positively correlated to well-being across a sample consisting of meditators, students, and a community sample, which was generally highly educated. It is important to note that only among practicing meditators was there a relationship between well-being and the observing facet of mindfulness (noticing or attending to internal or external experiences, such as smells), suggesting that experienced meditators are practiced in unbiased , rather than selective, observing of stimuli.

Jacobs et al. (2011) were the first to set out and examine the effects of mindfulness directly on meaning in life, as part of the purpose in life scale of Ryff’s (1989) well-being scale. Although this is the same well-being scale used in Baer’s (2009) study, here only the purpose in life scale was attended to, such that meaning in life could be better isolated. The participants of the study were instructed by a Buddhist scholar and practitioner in “the cultivation of attentional skills and the generation of benevolent mental states” (Jacobs et al., 2011; p. 668). While no significant changes were reported by the waitlisted controls, meditation participants experienced a significant improvement in their levels of meaning, as well as mindfulness itself, and a decrease on measures such as neuroticism.

In a study conducted by Kögler et al. (2015) examining the effects of existential behavioral therapy (EBT ) on informal caregivers to palliative patients, mindfulness was found to be significantly correlated to meaning in life. Although the study did not find that EBT had an impact on meaning, and nor was that relationship mediated by mindfulness, it was found that meaning in life increased significantly when mindfulness was practiced in a formal and informal manner, frequently and infrequently.

Most recently, Allan, Bott, and Suh (2015) attempted to link mindfulness to meaning in life, finding that it was positively correlated to the latter. However, they attempted to do so with the mediation of SDT , finding that awareness positively mediated the effect of mindfulness on meaning, indicating that awareness may be the key factor in explaining the role of mindfulness in meaning.

Practice Considerations

Based on this exciting research that is unfolding around character strengths, meaning, and mindfulness, as well as the integration of these areas, there are a number of considerations we suggest for practitioners. We discuss these ideas from two general perspectives: (1) single targeted interventions —brief strategies designed to elevate mindfulness of character strengths and life meaning; and (2) multifaceted integration programs —Here, we focus on mindfulness-based strengths practice (MBSP ) , a comprehensive, manualized program integrating character strengths and mindfulness that has been found in pilot studies to boost meaning and purpose for participants.

Targeted Interventions

Based on the emerging science, the use of signature strengths is aligned with individuals tapping into harmonious passion (Forest et al., 2012), a variable consistent with concepts relating to purpose and meaning. Moreover, interventions involving the use of signature strengths have been successful across several populations and cultures, and thus are a core element of the following interventions. We order these three interventions around time orientation—an intervention around past use, present use, and future use.

Source of Meaning

This exercise involves looking to the past.

-

1.

Wong (1998) has suggested seven central sources of meaning: relationships, intimacy, self-transcendence, self-acceptance, fairness, spirituality/religion, and achievement. As you review this list of potential sources where people commonly find greater meaning, name the two that have been the strongest sources of meaning in your life up until now.

-

2.

As you think about these two sources of meaning, consider how your character strengths (signature strengths and other strengths) have helped you capitalize on each in the past. Journal about the ways in which your character strengths have served as pathways to manifest these sources of meaning.

Strengths Alignment

This exercise looks at current work tasks and the potential of greater strengths use when engaging in these tasks. Researchers are drawing important links between signature strengths use and work that is a “calling” experience (Harzer & Ruch, 2012). This intervention on “aligning strengths ” highlights this effect.

-

1.

List the five tasks that you do most frequently at work (e.g., filing, leading team meetings, emailing clients, making sales calls, etc.).

-

2.

Review your top seven strengths in your character strengths profile from the VIA Survey.

-

3.

Write down one way you can use any one of your top strengths with each of the five work tasks (e.g., using kindness to lead a team meeting with sensitivity to others’ needs, using creativity to offer different perspectives when making a sales call, etc.).

-

4.

Explain how you will bring the character strength forth in the given task.

Point of clarification: This alignment exercise is asking individuals to both match one strength with each task (it is okay to repeat strengths more than once) and describe how they will do the task with their character strength in mind.

What Matters Most?

This “what matters most?” intervention, which builds upon the best possible self exercise (Meevissen, Peters, & Alberts, 2011), invites individuals to look to the future:

-

1.

Imagine your not-so-distant future—perhaps 6 months or 1 year from now. Name one area of your life that matters most to you—something that is so important and meaningful to you that you’d like to improve it (e.g., increasing happiness in marriage, graduating from college, improving physical health).

-

2.

List one way in which each of your five strongest signature strengths could be used as a “pathway of meaning” to help you improve this area and would therefore assist you in deepening your experience of what matters most.

This exercise immediately brings individuals to a key source of meaning and provides an immediate, easy-to-use, energizing, and individualized mechanism (signature strengths) as a pathway for getting there.

Multifaceted Integration Programs

Here we focus on the first program designed to integrate mindfulness and character strengths to foster a number of positive outcomes, including meaning—Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP ).

In merging the conceptual, scientific, and practical links between mindfulness and character strengths, and in integrating cross-cultural pilot group feedback, Niemiec (2014) developed MBSP —a program designed to explicitly focus on what is best in people. The rationale behind this link lives in the definition of each concept, as practicing mindfulness assumes the deployment of such character strengths as self-regulation and curiosity, while the mindful deployment of character strengths is the strengthening of mindfulness itself. As such, “the practice of mindfulness is strengths, and the practice of strengths is mindfulness” (Niemiec, 2014, p. 104).

MBSP involves didactic input, strength meditations, exercises, and discussions to encourage participants to enhance their engagement with life and to increase levels of meaning, improve problem-management, and catalyze flourishing (Niemiec, 2014). The program has substantive roots from existing and empirically tested and validated mindfulness programs, such as MBSR and MBCT . More specifically, the program is built from Thich Nhat Hanh’s mindfulness work based on mindful living (Nhat Hanh, 1993), and on the other hand, it is grounded from the character strengths research developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004). The unique aspect of MBSP is how mindfulness—usually a quiet and often calming approach—is combined with the energy and engagement that strengths provide, providing a unique synergy between these two forces of positive psychology (Niemiec, 2014).

The motivations for practicing meditation usually stem from the desire to deal with psychological emotional problems, and/or expand consciousness (Sedlmeier et al., 2012), and MBSP was created to support both, but is particularly aligned with the latter. Niemiec (2014) noted that MBSP can be likened to a third wave approach to psychological treatment, since it targets more meaningful living. This is also reflected in approaching MBSP as a practice, rather than “therapy,” as the goal is to improve and grow, rather than fix and perfect. As a result, MBSP is perfectly placed as a practice for any therapist, coach, consultant or even the general consumer, whether or not they have previous experience with mindfulness or character strengths.

In essence, MBSP operates from four universal assumptions of human beings (Niemiec, 2014). Firstly, individuals have the power to build their character strengths and mindfulness. Secondly, people can use their mindfulness ability and their character strengths to deepen self-awareness, foster insight, build a life of meaning and purpose, build relationships, and to reach their goals. Thirdly, individuals practiced in MBSP can use their core qualities in a more balanced and proficient manner. Finally, applying character strengths to mindfulness practice and mindful living will encourage individuals to become more consistent, as well as enabling themselves to reap more benefits from their mindfulness practice.

As a result of participating in a course of MBSP sessions, clients report clear experiences of growth. Niemiec (2014) explained that this growth is sometimes incremental, in which individuals are just beginning to challenge their old ways, while others experience the growth as an awakening, some reporting that they wish they could have gone through the process years earlier. In more operational terms, the changes can be subtle, substantial, or both—an individual may experience subtle changes between each session, amounting to a substantial change at the last session, when compared to when they had just started. The program is composed of eight, 2-h group sessions spanning over 8 weeks, though adaptations frequently occur. See Table 2 for a listing of the core themes of each week.

Each session focuses on a different aspect of mindfulness and character strengths, leading to the integration of the two concepts and their application in everyday life, problems, relationships, and planning for the future. MBSP suggests the weekly completion of experiential practices and exercises between sessions, allowing for deeper integration and benefit .

To be sure, MBSP is based in strong research foundations, however, it cannot yet be viewed as an evidence-based approach. Pilot research is promising, with participant-reports consistently noting benefits to meaning, purpose, well-being, management of problems, and other valued outcomes. Pilot studies reveal positive results relative to control groups (Briscoe, 2014; Niemiec, 2014) and case studies with several organizations have been reported (Niemiec & Lissing, 2016). As of this writing, randomized-controlled trials are underway (including a comparison of MBSP and CBT) and practitioners are testing and adapting it to a number of client populations and settings, including organizations, schools, teachers, parents of children with and without disabilities, young mothers, young adult entrepreneurs, people with severe mental illness, and caregivers, to name a few. Practitioners bring positive feedback from the field, reporting on a variety of positive effects they witnessed in their clients and students. One example of a unique benefit of MBSP that is frequently observed and reported is the strengthening and building of positive relationships (Niemiec & Lissing, 2016)—a finding that if found in future empirical studies may potentially have a robust association with life meaning and purpose. These successful feasibility and pilot studies warrant further research on MBSP as an intervention program to boost meaning, purpose, positive relationships, well-being, and other valued outcomes.

Future Recommendations

The field of positive psychology has unique and compelling aims to enhance flourishing in the general population (Seligman, 2011). Therefore, the creation and the scientific validation of interventions, practices, and programs for improving and enhancing positive qualities, not only reducing and alleviating problems (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013), needs to be established in order to accomplish these aims.

There appear to be substantial positive associations for mindfulness practices and character strengths practices; however, less is known about their interactions, synergistic outcomes, and relations with meaning and purpose. The targeted interventions we suggest offer some potential pathways for making strides in the practice of these areas. In addition, research suggests multi-component mindfulness therapies are more effective than mindfulness alone (Vøllestad, Nielsen, & Nielsen, 2012), thus programs such as Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice are well-positioned to be enhancers of meaning.

Key Takeaways

-

The endorsement of character strengths have been linked with life satisfaction and positive affect, self-acceptance, a sense of purpose in life, environmental mastery, physical and mental health, coping with daily stress, and resilience to stress and trauma. Character strengths also enhance the welfare of others in the individual’s social environment.

-

The deployment of character strengths have been linked with job and life satisfaction, academic goal-achievement, and positive affect. The deployment of signature strengths, in new and different ways, increases happiness and decreases depressive symptoms.

-

Mindfulness is beneficial in reducing clinical and non-clinical levels of anxiety and depression at post-treatment, with results maintained or improved at follow-up. Practicing mindfulness has positive effects across a wide range of domains in one’s everyday life. Many positive associations have been found between mindfulness and flourishing-related outcomes, such as subjective well-being, positive affect, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, optimism, self-regulation, self-compassion, positive relationships, vitality, creativity, health, longevity, and a range of cognitive skills.

-

Mindfulness can help one to express character strengths in a way that is balanced and sensitive to context, and character strengths can bolster an individual’s mindfulness practice by overcoming typical obstacles and barriers—thus supercharging mindfulness.

-

All 24 strengths have been linked with a meaningful life. Harmony and balance between strengths are also important for a meaningful life. Thus, any of the 24 character strengths can be targeted in an intervention or improved upon.

-

Mindfulness practice has been linked with a meaningful life.

-

Interventions that integrate these areas can be deployed across time orientation—the past can be used to target “sources of meaning” and the character strengths pathways, the present can be emphasized by examining the “alignment of signature strengths” with work tasks (linked with meaning/calling), and the future can be called upon with the “what matters most?” exercise that links strengths with a positive vision of oneself in the future.

-

Mindfulness-based strengths practice (MBSP ), a comprehensive, manualized program integrating character strengths and mindfulness, has been found in pilot studies to boost meaning and purpose for participants.

Notes

- 1.

VIA originally stood for “Values in Action” however the name was changed to emphasize the focus of this work which is the scientific exploration of character, not values per se. “VIA” is a word that stands on its own, in Latin meaning “the path,” and refers to the nonprofit organization that initiated and champions this character strengths work (VIA Institute on Character), the systematic classification system (VIA Classification), and the psychological measurement tool assessing strengths of character (VIA Survey).

References

Allan, B. A. (2015). Balance among character strengths and meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1247–1261. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9557-9

Allan, B. A., Bott, E. M., & Suh, H. (2015). Connecting mindfulness and meaning in life: Exploring the role of authenticity. Mindfulness, 6, 996. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0341-z

Andrewes, H. E., Walker, V., & O’Neill, B. (2014). Exploring the use of positive psychology interventions in brain injury survivors with challenging behavior. Brain Injury, 28, 965–971.

Baccarani, C., Mascherpa, V., & Minozzo, M. (2013). Zen and well-being at the workplace. TQM Journal, 25(6), 606–624. doi:10.1108/TQM-07-2013-0077

Baer, R. A. (2009). Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(1), 15–20.

Baer, R. A., & Lykins, E. L. M. (2011). Mindfulness and positive psychological functioning. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 335–348). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Williams, J. G. (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11(3), 191–206.

Berthold, A., & Ruch, W. (2014). Satisfaction with life and character strengths of non-religious and religious people: It’s practicing one’s religion that makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 876. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00876

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., … Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241.

Brdar, I., & Kashdan, T. B. (2010). Character strengths and well-being in Croatia: An empirical investigation of structure and correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 151–154. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.12.001

Briscoe, C. (2014). A study investigating the effectiveness of mindfulness-based strengths practice (MBSP). Thesis submitted to University of East London.

Brooks, J. E. (2010). Midshipman character strengths and virtues in relation to leadership and daily stress and coping. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Howard University, Washington, DC.

Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. doi:10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298

Carson, J. W., Carson, K. M., Gil, K. M., & Baucom, D. H. (2004). Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement. Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 471–494. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80028-5

Chodron, P. (1997). When things fall apart: Heart advice for difficult times. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Cullen, M. (2011). Mindfulness-based interventions: An emerging phenomenon. Mindfulness, 2, 186–193.

Desrosiers, A., Klemanski, D. H., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Mapping mindfulness facets onto dimensions of anxiety and depression. Behavior Therapy, 44(3), 373–384. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.001

Desrosiers, A., Vine, V., Klemanski, D. H., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013). Mindfulness and emotion regulation in depression and anxiety: Common and distinct mechanisms of action. Depression and Anxiety, 30(7), 654–661. doi:10.1002/da.22124

Duckworth, A. L., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1(1), 629–651. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154

Duffy, R. D., Bott, E. M., Allan, B. A., Torrey, C. L., & Dik, B. J. (2012). Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 50–59. doi:10.1037/a0026129

Engel, H. R., Westman, M., & Heller, D. (2012). Character strengths, employees’ subjective well being and performance: An experimental investigation. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv.

Forest, J., Mageau, G. A., Crevier-Braud, L., Bergeron, E., Dubreuil, P., & Lavigne, G. L. (2012). Harmonious passion as an explanation of the relation between signature strengths’ use and well-being at work: Test of an intervention program. Human Relations, 65(9), 1233–1252. doi:10.1177/0018726711433134

Frankl, V. E. (1965). The doctor and the soul: From psychotherapy to logotherapy. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Wyss, T. (2013). Strength-based positive interventions: Further evidence for their potential in enhancing well-being and alleviating depression. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1241–1259. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9380-0

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2012). When the job is a calling: The role of applying one’s signature strengths at work. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(5), 362–371. doi:10.1080/17439760.2012.702784

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1482–1486. doi:10.1177/0956797614531799

Jacobs, T. L., Epel, E. S., Lin, J., Blackburn, E. H., Wolkowitz, O. M., Bridwell, D. A., … Saron, C. D. (2011). Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(5), 664–681. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.010

Jarden, A., Jose, P., Kashdan, T., Simpson, O., McLachlan, K., & Mackenzie, A. (2012). [International Wellbeing Study]. Unpublished raw data.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

Keng, S., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

Kerr, S. L., O’Donovan, A., & Pepping, C. A. (2015). Can gratitude and kindness interventions enhance well-being in a clinical sample? Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(1), 17–36. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9492-1

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

Kögler, M., Brandstätter, M., Borasio, G. D., Fensterer, V., Küchenhoff, H., & Fegg, M. J. (2015). Mindfulness in informal caregivers of palliative patients. Palliative & Supportive Care, 13(1), 11–18. doi:10.1017/S1478951513000400

Kowalski, R. M., Allison, B., Giumetti, G. W., Turner, J., Whittaker, E., Frazee, L., et al. (2014). Pet peeves and happiness: How do happy people complain? The Journal of Social Psychology, 154(4), 278–282. doi:10.1080/00224545.2014.906380

Langer, E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley/Addison Wesley Longman.

Lavy, S., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Bareli, Y. (2014a). Strengths deployment as a mood-repair mechanism: Evidence from a diary study with a relationship exercise group. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(6), 547–558. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.936963

Lavy, S., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Bareli, Y. (2014b). My better half: Strengths endorsement and deployment in married couples. Journal of Family Issues. doi:10.1177/0192513X14550365

Leontopoulou, S., & Triliva, S. (2012). Explorations of subjective wellbeing and character strengths among a Greek University student sample. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2, 251–270.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Linley, P. A., Nielsen, K. M., Gillett, R., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). Using signature strengths in pursuit of goals: Effects on goal progress, need satisfaction, and well-being, and implications for coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 5, 6–15.

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel: Hebrew adaptation of the VIA inventory of strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 41–50. doi:10.1177/1069072715580322

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2015). Going the extra mile: Perseverance as key character strength at work. Journal of Career Assessment, 1–13. doi:10.1177/1069072715580322

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Steger, M. F. (2010). Character strengths and well-being among volunteers and employees: Towards an integrative model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 419–430.

Madden, W., Green, S., & Grant, A. M. (2011). A pilot study evaluating strengths-based coaching for primary school students: Enhancing engagement and hope. International Coaching Psychology Review, 6, 71–83.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper.

Mayerson, N. M. (2013). Signature strengths: Validating the construct. Presentation to International Positive Psychology Association, Los Angeles, CA, 82–83. doi:10.1037/e574802013-112

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology, 13(3), 242–251. doi:10.1037/a0017152

Meevissen, Y. M. C., Peters, M. L., & Alberts, H. J. E. M. (2011). Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: Effects of a two week intervention. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42, 371–378.

Nhat Hanh, T. (1979). The miracle of mindfulness: An introduction to the practice of meditation. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Nhat Hanh, T. (1993). For a future to be possible: Commentaries on the five mindfulness trainings. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

Nhat Hanh, T. (1998). The heart of the Buddha’s teaching. New York, NY: Broadway.

Nhat Hanh, T. (2009). Happiness. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press.

Niemiec, R. M. (2012). Mindful living: Character strengths interventions as pathways for the five mindfulness trainings. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(1), 22–33.

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives on positive psychology (pp. 11–30). New York, NY: Springer.

Niemiec, R. M. (2014). Mindfulness and character strengths: A practical guide to flourishing. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing.

Niemiec, R. M., & Lissing, J. (2016). Mindfulness-based strengths practice (MBSP) for enhancing well-being, life purpose, and positive relationships. In I. Ivtzan & T. Lomas (Eds.), Mindfulness in positive psychology: The science of meditation and wellbeing (pp. 15-36). New York: Routledge.

Niemiec, R. M., Rashid, T., & Spinella, M. (2012). Strong mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness and character strengths. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(3), 240–253.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Methodological issues in positive psychology and the assessment of character strengths. In A. D. Ong & M. van Dulmen (Eds.), Handbook of methods in positive psychology (pp. 292–305). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College and Character, 10, 1–10.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603–619.

Parks, A. C., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). Positive interventions: Past, present, and future. In T. B. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 140–165). Oakland, CA: Context Press/New Harbinger Publications.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), 25–41. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 149–156. doi:10.1080/17439760701228938

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Praissman, S. (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reduction: A literature review and clinician’s guide. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(4), 212–216. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00306.x

Proyer, R. T., Annen, H., Eggimann, N., Schneider, A., & Ruch, W. (2012). Assessing the “good life” in a military context: How does life and work-satisfaction relate to orientations to happiness and career-success among swiss professional officers? Social Indicators Research, 106(3), 577–590.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50-79 years: Long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 997–1005. doi:10.1080/13607863.2014.899978

Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Buschor, C. (2013). Testing strengths-based interventions: A preliminary study on the effectiveness of a program targeting curiosity, gratitude, hope, humor, and zest for enhancing life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 275–292. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9331-9

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sedlmeier, P., Eberth, J., Schwarz, M., Zimmermann, D., Haarig, F., Jaeger, S., & Kunze, S. (2012). The psychological effects of meditation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1139–1171. doi:10.1037/a0028168

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1999). The president’s address. American Psychologist, 54, 559–562.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York, NY: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2015). Chris Peterson’s unfinished masterwork: The real mental illnesses. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 3–6. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.888582

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Shapiro, D. H. (1982). Overview: Clinical and physiological comparisons of meditation with other self-control strategies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 267–274.

Steger, M. F. (2009). Meaning in life. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology (pp. 679–687). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. doi:10.1177/1069072711436160

Steger, M. F., Pickering, N. K., Shin, J. Y., & Dik, B. J. (2010). Calling in work: Secular or sacred? Journal of Career Assessment, 18(1), 82–96. doi:10.1177/1069072709350905

Stern, D. N. (2004). The present moment: In psychotherapy and everyday life. New York, NY: Norton.

Sugiura, Y. (2004). Detached mindfulness and worry: A meta-cognitive analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(1), 169–179. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.08.009

Van Dam, N. T., Hobkirk, A. L., Sheppard, S. C., Aviles-Andrews, R., & Earleywine, M. (2014). How does mindfulness reduce anxiety, depression, and stress? An exploratory examination of change processes in wait-list controlled mindfulness meditation training. Mindfulness, 5(5), 574–588. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0229-3

Vella-Brodrick, D., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Three ways to be happy: Pleasure, engagement, and meaning—Findings from Australian and US samples. Social Indicators Research, 90(2), 165–179. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9251-6

Vøllestad, J., Nielsen, M. B., & Nielsen, G. H. (2012). Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 239–260. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02024.x

Weber, M., & Ruch, W. (2012). The role of character strengths in adolescent romantic relationships: An initial study on partner selection and mates’ life satisfaction. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1537–1546.

Wong, P. T. P. (1998). Spirituality, meaning, and successful aging. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 359–394). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Littman-Ovadia, H., Niemiec, R.M. (2016). Character Strengths and Mindfulness as Core Pathways to Meaning in Life. In: Russo-Netzer, P., Schulenberg, S., Batthyany, A. (eds) Clinical Perspectives on Meaning. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41397-6_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41397-6_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-41395-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-41397-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)