Abstract

Mindfulness and character strengths significantly contribute to psychological wellbeing in various contexts. Empirical studies further imply that mindfulness-based interventions can cultivate a wide range of strengths, which in turn facilitate the wellbeing of individuals. However, no study has examined this hypothesis. The current study underpins this argument with empirical pieces of evidence from cross-sectional (Study 1) and longitudinal (Study 2) data by investigating the relationship between character strengths, mindfulness, and psychological wellbeing among community (n = 375) and undergraduate populations (n = 229). Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, Brief Strengths Scale, and Flourishing Scale were administrated. As hypothesized, the results of the cross-sectional investigation confirm that mindfulness and character strengths are conceptually related constructs with significant contributions to psychological wellbeing. Temperance Strength and Interpersonal Strength further mediate the relationship between Observing facet of mindfulness and Flourishing. Furthermore, investigating the relationship among mindfulness, strengths, and psychological wellbeing using Longitudinal Mediation Modeling reveals a clear picture. After the baseline of the outcomes is controlled, the 6-month longitudinal study indicates that the past level of Observing facet of mindfulness can predict the present level of Temperance Strength, which in turn predicts future Flourishing. These results highlight the importance of Observing facet in mindfulness and Temperance Strength, which provide another possible explanation on how and why mindfulness can affect psychological wellbeing among general populations. Future Strength-based Mindfulness Intervention Programs can be developed based on these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Mindfulness pertains to “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn 1990, p. 145). It initially appeared as therapy to treat psychopathology. Most findings show that mindfulness therapies (e.g., Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy) achieve good efficacy, and that most participants experience a decrease in psychological distress and inappropriate behaviors through a period of intervention that ranges from several weeks to several months (Didonna 2009). Shapiro et al. (2006) argued that accumulated evidence from the past 20 years of empirical research has led to addressing the question, “How do mindfulness-based interventions actually work?” (p. 374). Some studies further investigated the mechanisms behind mindfulness-based interventions in clinical populations. For example, cognitive appraisals (Schmertz et al. 2012) and drinking motives (Vinci et al. 2016) have been indicated as the mediators between mindfulness and social anxiety and problematic alcohol use, respectively. In recent years, the applications of mindfulness have gone beyond clinical fields. Several studies have been conducted on elderly care (Cruz et al. 2016), workplaces (Aikens et al. 2014), schools (Harris et al. 2016), and other settings; these works have focused on the promotion of psychological wellbeing through mindfulness-based interventions and trainings. The present study aims to explore the reason and manner in which mindfulness can affect psychological wellbeing among general populations.

Some studies have found that mindfulness intervention is positively related to positive stress coping (Walach et al. 2007), psychological wellbeing (Xu et al. 2014), and job performance (Dane and Brummel 2014). Hülsheger et al. (2013) conducted a multi-method study to examine the roles of trait mindfulness and mindfulness-related training in improving job satisfaction among employees. The 219 employees were required to complete a diary and a questionnaire package each day for assessing trait mindfulness and job satisfaction in a 5-day study. Multilevel structural equation modeling reveals a positive relation between trait mindfulness and job satisfaction at within- and between-individual levels (Hülsheger et al. 2013). A control group and a mindfulness self-training intervention group (performing activities including the Body Scan, Three-Minute Breathing Space, Daily Routine Activities, and Raisin Exercise) were established as the experimental field study to further examine whether mindfulness is the causal determinant on another 64 employees (Hülsheger et al. 2013). The findings indicated that individuals in the mindfulness-related training group are more satisfied with their job than the control group (Hülsheger et al. 2013). The effects of a standardized and community-based mindfulness training on psychological wellbeing and trait mindfulness among community populations have also been examined (Szekeres and Wertheim 2014). A total of 172 participants attended a 10-day intervention program. Pre-, post-, and follow-up tests were conducted to examine the changes in psychological wellbeing (Szekeres and Wertheim 2014). The findings demonstrated that the 90 individuals in the experimental group show positive effects in increasing wellbeing and trait mindfulness, especially in the present-moment awareness component of mindfulness (Szekeres and Wertheim 2014).

To date, most studies on mindfulness have been focused on applied studies (i.e., mindfulness-related trainings and interventions) as opposed to theoretical ones because this concept and its corresponding theories have been developed through practice. In the past few years, only limited studies have been conducted to explore the underlying mechanisms of mindfulness in affecting wellbeing. Malinowski and Hui (2015) found that positive job-related effect and psychological capital mediate the relationship between mindfulness and wellbeing among employees. Another neuroscience study suggested that executive function and self-regulation may be the underlying mechanisms between mindfulness and positive or negative effect (Short et al. 2016). Additional comprehensive studies (e.g., longitudinal design) are needed to further clarify the issue.

Baer and Lykins (2011) suggested that mindfulness should be considered “an attentional stance, or a way of relating to one’s present-moment experiences, that probably cultivates a wide range of strengths” (p. 341). This argument implies that mindfulness should be naturally connected with character strength. Character strengths are morally valued positive qualities manifested through cognition, emotion, motivation, and action, which are beneficial to oneself and others (Peterson and Seligman 2004). Basing on a systematic framework for studying character strengths called Values in Action (VIA) Classification (Peterson and Seligman 2004), different researchers in the United States (McGrath 2015; Shryack et al. 2010), Hong Kong (Ho et al. 2016), and China (Duan et al. 2012b, 2013) independently revealed a potentially universal Three-Dimensional Model of Character Strengths using various large samples and advanced statistical methods, which partly solved the factor issues in conceptualization and assessment of character strengths (Ho et al. 2014a, b). The three general character strengths include (Duan et al. 2012b, 2013; Ho et al. 2014a, b, 2016; McGrath 2015) Interpersonal Strength (defined as the love, concern, and gratitude of a person toward others; reflecting the components of kindness, teamwork, fairness, love and be loved, authenticity, leadership, forgiveness, and gratitude), Intellectual Strength (defined as the curiosity and zest for creativity of an individual; reflecting the components of humor, curiosity, zest, creativity, perspective, hope, social intelligence, beauty, bravery, and belief), and Temperance Strength (defined as people who persist in achieving goals and exhibit self-control; reflecting the components of judgment, prudence, regulation, perseverance, learning, and modesty). The three character strengths show positive correlations with satisfaction with life (Duan et al. 2012a), flourishing (Tang et al. 2016), hope and gratitude (Duan et al. 2013), resilience (Duan et al. 2015a), and post-traumatic growth (Duan and Guo 2015). They show negative correlations with depression and anxiety (Duan et al. 2013), psychological distress (Duan et al. 2015b), stress (Duan 2016a), pathological Internet use (Zhang et al. 2014), and post-traumatic stress disorder (Duan et al. 2015a). Character strength-based interventions can effectively increase wellbeing among various populations (e.g., Duan et al. 2014; Parks and Biswas-Diener 2013; Proyer et al. 2015). In addition, researchers have proposed that character strengths can and should be integrated into clinical practice to help clients alleviate suffering and increase wellbeing (Boardman and Doraiswamy 2015) rather than simply focus on the negative.

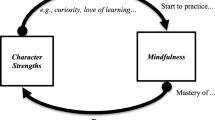

Previous studies have demonstrated that mindfulness can cultivate a wide range of components involved in the abovementioned three-dimensional character strengths model that can improve mental health outcomes. A study has indicated that a high level of mindfulness is usually associated with a high level of authenticity in Interpersonal Strength (Lakey et al. 2008). More importantly, mindfulness training enhances the strength of the components of Interpersonal Strength. After participating in the Mindfulness-based Relationship Enhancement program, couples have significantly increased their closeness, relationship satisfaction, autonomy, relatedness, as well as acceptance of each other (Carson et al. 2004). Researchers have argued that mindfulness is connected to a wide range of receptiveness, including creativity, curiosity, open-mindedness, openness to experiences, and learning (Brown and Ryan 2003). In the operational definition of mindfulness, “self-regulation of attention so that it is maintained on immediate experience, thereby allowing for increased recognition of mental events in the present moment and adopting a particular orientation toward one’s experience that is characterized by curiosity, openness, and acceptance” (Bishop et al. 2004, p. 232), curiosity is one of the two central factors, and it is recognized as an important orientation of one’s attention (Bishop et al. 2004). Conceptually, the degree of curiosity is an important factor that determines the level of mindfulness, and curiosity is a central component of Intellectual Strength in the three-dimensional model of character strengths (Duan et al. 2012b; Ho et al. 2016). Intervention studies have illustrated that mindfulness training increases the different aspects of Intellectual Strength. For example, the “to be open and curious” section of mindfulness-based intervention effectively increases the level of curiosity of a couple (Carson et al. 2004). Other studies have indicated that divergent thinking is promoted through the meditation approach (mindfulness practice), especially through the open monitoring of the present moment, to facilitate the generation of new ideas (Colzato et al. 2012). Self-regulation is the other significant part of the operational definition of mindfulness (Bishop et al. 2004), and it is highlighted in Temperance Strength of the three-dimensional model of character strengths (Duan et al. 2012b; Ho et al. 2016). de Vibe et al. (2015) argued that self-regulation should be recognized as an important and interesting factor in mindfulness studies because a high level of self-regulation predicts the increased effect of mindfulness intervention. Moreover, the mindfulness approach remains effective for those who originally have a high level of self-regulation (Bowlin and Baer 2012).

Most of the aforementioned studies have focused on intervention research, which indicates that mindfulness training significantly enhances strengths such as authenticity, curiosity, and self-regulation, which in turn facilitate health-related outcomes. Therefore, hypothesizing that these cultivated strengths may be the underlying mechanisms behind mindfulness-based interventions is reasonable. Information used to gauge the relationship between character strengths and mindfulness is insufficient, according to these intervention studies. Moreover, empirical studies on this topic are lacking, as only one study has investigated the connections between the aforementioned two constructs (Duan 2016b). Thus, the present study aims to fill this gap using advanced statistical methods (i.e., longitudinal structural equation modeling) and study design (i.e., cross-sectional and longitudinal design).

The overall objective of the present study is to study the reason and manner in which mindfulness can affect psychological wellbeing among the general populations. The abovementioned discussion implies that mindfulness trainings can cultivate a wide range of components, such as authenticity, curiosity, and self-regulation, involved in the three-dimensional model of character strengths. These strengths consequently facilitate health-related outcomes. Therefore, character strengths should have a mediating role in the relationship between mindfulness and mental health. Accordingly, the present study hypothesizes: (1) mindfulness and the three character strengths (i.e., Interpersonal Strength, Intellectual Strength, and Temperance Strength) are positively correlated with each other; (2) mindfulness and character strengths significantly contribute to psychological wellbeing; (3) the three character strengths mediate the relationship between mindfulness and psychological wellbeing; and (4) over time, past mindfulness can predict present strengths, which in turn can predict future psychological wellbeing. To examine these hypotheses, cross-sectional (Study 1) and longitudinal (Study 2) studies are conducted. The results will enhance the understanding of mindfulness research and facilitate the application of mindfulness and strengths in the future.

2 Study 1: Cross-Sectional Investigation

This study aims to examine the relationships among the mindfulness, character strengths, and psychological wellbeing of a community sample. The relative roles and effects of mindfulness and character strengths in affecting psychological wellbeing are also clarified. Previous studies recognized “present-centered awareness/attention” and “non-judgmental attitude” as two commonly accepted components of mindfulness (Bishop et al. 2004; Lau et al. 2006; Quaglia et al. 2014). In addition, some empirical studies further demonstrated that the Observing facet and Non-judging facet are core components in understanding mindfulness among meditators and non-meditators through confirmatory factor analysis and cluster analysis (Coffey et al. 2010; Lilja et al. 2013; Peters et al. 2015; Truijens et al. 2015). Accordingly, the present study adopts the two-facet model of mindfulness to create a framework for the concept. In addition, psychological wellbeing is reflected by the individual level of flourishing, which indicates the important aspects of wellbeing of humans (Diener et al. 2010). Taking these adoptions together, this exploratory study investigates the associations between mindfulness and character strength in the mental wellbeing field. The results will deepen the understanding of the two psychological constructs and the potential mechanism behind them and will facilitate related practice in the future.

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants and Procedures

All the participants were recruited from communities and voluntarily joined in this investigation. They were invited to complete a package of paper-and-pencil questionnaire and demographic information. A written informed consent was obtained before completing the questionnaire. Participants with active physical and mental illnesses were excluded. The final data pool was composed of 375 adults from 11 different communities in a large urban southwestern city in China. Data were collected in May 2014 from 198 females (52.8%) and 176 males (46.9%), whose ages ranged from 18 to 88 years (M = 32.10, SD = 10.07). Among the 375 participants, 6 completed primary school education, 172 completed middle school education, and 182 completed higher education and above. A total of 204 of the participants were married, whereas 108 of them were single. In addition, 39 of them were in a relationship. None of them reported meditation experience. Ethical approval was provided by the College Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee, City University of Hong Kong.

2.1.2 Measurements

2.1.2.1 Brief Strengths Scale (BSS)

Ho et al. (2016) developed a 12-item brief scale for measuring the three character strengths (Interpersonal Strength, Intellectual Strength, and Temperance Strength; four items per strength) among individuals with or without mental health issues. Basing on their own actual situation, the participants were required to rate the extent to which they disagree (1 = extremely disagree) or agree (7 = extremely agree) with each item on a seven-point Likert scale. Subscale scores were obtained by taking the sum of the corresponding item scores and dividing the number of items. High scores indicate that an individual has a particular strength to a great extent. Sample items include “I am a persistent person” (Temperance Strength), “I strongly treasure my relationships with people around me” (Interpersonal Strength), and “I think there are a lot of interesting things in this world to be explored” (Intellectual Strength). A more recent study revised the scale for developing a highly stable nine-item measurement (three items per strength) among general populations (Duan and Ho 2016). The three-factor structure of character strengths was invariant among community populations across gender, age, education levels, and marital status (Duan and Ho 2016). In the current community sample, the Cronbach’s alpha of the Interpersonal Strength subscale is 0.68; that of Intellectual Strength is 0.69; and that of Temperance Strength is 0.80.

2.1.2.2 Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The original English version of the FFMQ was constructed according to the factor analysis of a combined item pool, and EFA and CFA demonstrate a five-factor solution for FFMQ (Baer et al. 2006). The internal consistency of the FFMQ ranges from 0.67 to 0.93 (Baer et al. 2006). Coffey et al. (2010) demonstrated that observing (i.e., present-centered attention; eight items) and non-judging (i.e., acceptance of internal experience; eight items) are the two clear factors of mindfulness through CFA. Thus, the two subscales of FFMQ (i.e., observing and non-judging) were adopted in the current project. Sample items include “I pay attention to sensations such as the wind in my hair or the sun on my face” (observing) and “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions” (non-judging). Participants were required to answer 16 items using a five-point Likert scale (1 = never or rarely true to 5 = very often or always true). All items in the non-judging subscale have reverse scoring. A high mean score in each subscale reflects high levels of the different aspects of mindfulness. The psychometric characteristics of the Chinese version of FFMQ were well established in previous studies (Deng et al. 2011). The Cronbach’s alpha of the observing subscale is 0.68, and that of the non-judging subscale is 0.63.

2.1.2.3 Flourishing Scale (FS)

FS is used to measure the important aspects of wellbeing of humans through eight items (Diener et al. 2010), such as engagement, relationship, competence, and life purpose. Sample items include “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities” and “I am optimistic about my future.” Participants were required to provide their individual answers according to a seven-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). None of the items was reversely coded. Mean scoring was adopted, with a high score denoting a high function and success levels of the respondent. Positive psychometric properties (e.g., univariate structure and high Cronbach’s alpha) characterized the scale (Diener et al. 2010). The simplified Chinese version of the scale was validated by two studies (Duan and Xie 2016; Tang et al. 2016), and it was demonstrated to have satisfactory reliabilities and validities. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s alpha of the total scale is 0.89.

2.1.3 Data Analysis Plan

First, descriptive statistics and partial correlations were obtained for the three character strengths, the two facets of mindfulness, and Flourishing. Second, hierarchical regressions using the Enter method were performed to explore the different functions of character strengths and mindfulness in predicting psychological wellbeing (Zeidner et al. 2008). In the hierarchical regression, Flourishing was set as the dependent variable. The facets of mindfulness were entered in Step 1, and the three character strengths were entered in Step 2. A previous study has indicated that a particular variable or scale expected to explain at least 5.00% unique variance in the specific outcome can be recognized as independent of other similar ones (Zeidner et al. 2008). Third, structural equation modeling was used to test the mediating role of character strengths. The three character strengths were set as the mediators in the mindfulness–psychological wellbeing relationship. Path analysis was adopted to delete the non-significant paths individually. CFI, TLI, and RMSEA were adopted to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the models. SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used to conduct the abovementioned analyses.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

The mean and standard deviation of the character strengths, mindfulness, and Flourishing are listed in Table 1. Interpersonal Strength is the most endorsed strength (Mean = 6.08, SD = 0.71), and Non-judging has a lower mean score (Mean = 2.51, SD = 0.50) than Observing. The three character strengths and Observing have significantly positive associations with Flourishing (r = 0.25–0.45; p < 0.01), whereas Non-judging is negatively and significantly related to Flourishing (r = −0.15; p < 0.01). Table 1 indicates that Observing is positively related to all the three character strengths (r = 0.21–0.33; p < 0.01), whereas Non-judging has a negative association with all of them (r = −0.12 to −0.27; p < 0.01). As reflected in Table 1, before and after the demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, education, and marital status) were controlled, the correlation statistics change insignificantly. Thus, the demographic variables were not controlled in the following analyses.

2.2.2 Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression was conducted. Collinearity statistics indicate that all VIF values are less than 5, which reflects that the multicollinearity of mindfulness and strengths is not an issue in the present data (Table 2). In Step 1 of the hierarchical regression, the two facets of mindfulness contribute 5.70% of the variances of Flourishing. In Step 2, the three character strengths add another 21.80% (27.40–5.70%) of the variances above mindfulness. Therefore, the hierarchical regression reveals that the three character strengths contribute more to Flourishing than mindfulness. Standardized β shows that Temperance Strength is the strongest predictor among the strengths (Table 2).

2.2.3 Mediation Effect Analysis

Structural equation model was constructed with Flourishing as the outcome variable. According to the results described above, only the Observing facet of mindfulness was set as the independent variable. In the model, the three character strengths were set as mediators, and Flourishing was set as the dependent variable. The item parceling method was used to construct the three observed variables for each latent variable. A revised structural equation model that shows an excellent goodness-of-fit index (χ 2 = 101.709, df = 50, CFI = 0.956, RMSEA = 0.053, 90% CI = [0.038, 0.067], SRMR = 0.065) was established (Fig. 1). The indirect effect was then examined by the Sobel test (Sobel 1982) using the Mplus software. The test results indicate a significant indirect effect of mediation (Temperance Strength: Est./S.E. = 4.242, p < 0.001; Interpersonal Strength: Est./S.E. = 3.484, p < 0.001). Generally, Temperance Strength and Interpersonal Strength mediate the relationship between Observing and Flourishing.

2.3 Brief Discussion

The three character strengths and the two facets of mindfulness were conceptualized as dispositional qualities, which play a significant role in enhancing mental wellbeing and reducing mental disorders. A two-facet mindfulness structure (i.e., Observing and Non-judging) was adopted in the current study, according to the widely used operational definition of Bishop et al. (2004) and the essence of mindfulness (Coffey et al. 2010). On the basis of their cross-cultural characteristics, shared components, and similar functions, the three character strengths were hypothesized to be positively related to the components of mindfulness. However, the current study found that only a part of mindfulness (i.e., the Observing facet) is positively related to the three character strengths (r = 0.21–0.33; p < 0.01), whereas the other part of mindfulness (i.e., the Non-judging facet) is negatively related to them (r = −0.12 to −0.27; p < 0.01). In addition, these correlation coefficients are relatively weak (i.e., less than 0.40). These results partly imply that character strengths and mindfulness are related but different, and they further suggest that the two facets of mindfulness are different.

In addition, the hierarchical regressions reveal that character strengths and mindfulness may have different foci in affecting psychological wellbeing. Specifically, the three strengths are related to enhancing mental wellbeing (Quinlan et al. 2012), whereas mindfulness is related to reducing mental ill-being (Coffey et al. 2010). Although strengths and mindfulness are important contributors to mental health (Smith and Gallo 2001; Smith and Ruiz 2004; Stone et al. 1980), they use different paths. For example, strengths may increase mental wellbeing through the Health Behavior Model (Armitage and Conner 2000), whereas mindfulness may reduce mental ill-being through the Illness Behavior Model (Cioffi 1991).

On the one hand, the Health Behavior Model (Armitage and Conner 2000) suggests that different characteristics of personality usually adopt different health-related behaviors to increase mental wellbeing. Individuals with high levels of self-control, as reflected by Temperance Strength, usually show healthy sleep (Duggan et al. 2014) and eating (Olsen et al. 2015) behaviors, which further enhance wellbeing. On the other hand, the Illness Behavior Model (Cioffi 1991) suggests that different characteristics of personality usually adjust attention to sensations to decrease mental ill-being. A recent review article has indicated that mindfulness training is effective in improving the attention of participants in treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Mitchell et al. 2015). However, whether mental wellbeing is enhanced or mental ill-being is reduced, the overall mental health level is improved.

The incremental validity of the character strengths in explaining psychological wellbeing indicates the functional differences between character strengths and mindfulness. The mediation analyses further involve the character strengths as potential mechanisms of mindfulness in affecting mental health. As shown by the mediation model, Temperance Strength and Interpersonal Strength mediate the relationship between the Observing facet of mindfulness and Flourishing. Avey et al. (2008) previously investigated mindfulness and psychological capital in an organizational context and found that mindfulness and psychological capital, as well as their interactions, play an important role in the changes at the individual level (e.g., positive emotion) and at the organizational level (e.g., positive development). Roche et al. (2014) recently extended the results and further confirmed the mediation effect of psychological capital on the mindfulness–wellbeing relationship. The results obtained by the previous and current studies demonstrate that engaging in health promotion, meaningful life-seeking, and resilience development are all mental processes that require being mindful of the positive guidance in these processes.

In summary, the significant correlations and the different contributions to psychological wellbeing indicate that character strengths and mindfulness can be considered conceptually related but functionally different constructs. These constructs work together to contribute to mental wellbeing. Mediation analyses partly elucidate the strengths as a possible internal mechanism of mindfulness in affecting psychological wellbeing. Moreover, the Observing facet of mindfulness and Temperance Strength in the three-dimensional character strengths model are the relatively important factors among the other components of mindfulness and strengths. However, the cross-sectional design prevents the conclusion of a temporal relationship. Thus, a longitudinal design was conducted to reveal a clear relationship in Study 2.

3 Study 2: Longitudinal Verification

The objective of this study is to examine the temporal relationships of the mediation models obtained in Study 1. The effect of the baseline state of psychological wellbeing was included.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants, Procedures, and Measurements

The participants involved in this longitudinal study came from two universities in Chongqing and one university in Nanjing, Mainland China. Participant recruitment was announced on the Bulletin Board System of each university in mid-September 2014. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals 18 years old and above, (2) mother language is Chinese, (3) sophomore or junior year, (4) having 20 min to complete a questionnaire package, and (5) willing to provide a cell phone number and an email address for further communication. Participants with active physical and mental illnesses were excluded. The participants who were interested in the research could contact the investigator through the email address or cell phone number published in the announcement. They were invited to independently complete the paper-and-pencil questionnaire within one week after agreeing to participate. The participants were asked to provide a written informed consent before completing the questionnaire.

The first, second, and third data collection procedures were conducted in early October 2014 (Time 1, T1), late December 2014 (Time 2, T2), and early April 2015 (Time 3, T3). Basing on previous studies (e.g., Chua et al. 2014; Gallagher et al. 2014), different variables were collected at different time points to reduce cognitive loadings. At Time 1, all participants were requested to complete the BSS, Observing subscale of FFMQ, and FS; at Time 2, the participants were required to complete the BSS; and at Time 3, they were asked to complete the FS. The procedures complied with the guidelines for examining the longitudinal mediation effect (Cole and Maxwell 2003): predictors and baseline outcomes are measured at Time 1; mediators are measured at Time 2; and the outcomes are measured at Time 3. The email addresses and cell phone numbers were collected in the first data collection period for sending reminders only. After the third investigation was completed (early April 2015), the study objective and corresponding interpretations were explained to the participants. Personal information was kept confidential and destroyed after the completion of the research project.

A total of 229 undergraduates successfully completed the longitudinal study. Among the participants, 110 females (48.00%) and 119 males (52.00%) were included in the final data pool. The age range was 18–22 years (M = 19.41, SD = 0.66). Among the participants, 172 (75.10%) were single, and 57 (24.90%) were in a relationship. None of the participants reported a history of serious illness, long-term medication, and meditation experience.

3.1.2 Data Analysis Plan

The means and standard deviations of the two character strengths (i.e., Temperance Strength and Interpersonal Strength), Observing, and Flourishing at different time points were obtained through descriptive analysis. The partial correlations among these variables at different time points were also calculated. Following the guidelines of Cole and Maxwell (2003) in examining the longitudinal mediation effect, an independent variable was measured at Time 1 (i.e., Observing), the mediated variables were measured at Time 2 (i.e., Temperance Strength and Interpersonal Strength), and the outcome variable was measured at Time 3 (i.e., Flourishing). The baselines of Temperance Strength, Interpersonal Strength, and Flourishing at Time 1 were also measured and controlled in the longitudinal mediation model. Structural equation modeling was adopted and conducted with bootstrap resampling of 10,000 iterations and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. The obtained statistics were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used to conduct the abovementioned analyses.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Descriptive and Correlation Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of Observing (Time 1), Temperance Strength (Time 1 and Time 2), Interpersonal Strength (Time 1 and Time 2), and Flourishing (Time 1 and Time 3) are listed in Table 3. The association between Temperance Strength at Time 1 and Interpersonal Strength at Time 2 is insignificant (r = 0.10; p = 0.12), and the other correlations between the researched variables and Flourishing are positively significant. Similar to Study 1, the demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, education, and marriage status) cannot significantly affect the outcomes (see Table 3). Thus, none of demographic variable needed to be controlled.

3.2.2 Longitudinal Mediation Analysis

On the basis of the model obtained in Study 1 and the guidelines, a Longitudinal Mediation Model (Cole and Maxwell 2003) was constructed to reveal the temporal relationships among the Predictor (Time 1), Mediator (Time 2), and Outcomes (Time 3). In the current study, (1) Observing at Time 1 was set as the predictor of Temperance Strength at Time 2 and Interpersonal Strength at Time 2; (2) Temperance Strength at Time 1 was set as the predictor of Temperance Strength at Time 2; (3) Interpersonal Strength at Time 1 was set as the predictor of Interpersonal Strength at Time 2; and (4) Flourishing at Time 1, Temperance Strength at Time 2, and Interpersonal Strength at Time 2 were set as the predictors of Flourishing at Time 3. The variables at Time 1, including Observing, Temperance Strength, Interpersonal Strength, and Flourishing, were set as correlated. The results indicate that Observing at Time 1 cannot significantly predict Interpersonal Strength at Time 2 (Estimate = 0.076, S.E. = 0.114, p = 0.51; 95% CI = [− 0.141, 0.303]), and the CFI of the model is unacceptable (CFI = 0.543). Accordingly, the variable of Interpersonal Strength was removed from the original model. The revised model that shows an acceptable goodness-of-fit index (χ 2 = 9.887, df = 3, CFI = 0.957, RMSEA = 0.100, 90% CI = [0.035, 0.173], SRMR = 0.050) was established (Fig. 2). The mediation analysis produces a significant indirect effect from Observing on the future Flourishing (Effect = 0.068, S.E. = 0.033, 95% CI = [0.013, 0.142], p = 0.037).

3.3 Brief Discussion

This longitudinal study further examines the mediating role of the character strengths between the mindfulness (i.e., Observing) and psychological wellbeing of a Chinese college population.

The Observing facet of mindfulness referred to the “present-centered attention” (Coffey et al. 2010) and “attention with self-regulation” in previous studies (Bishop et al. 2004), which highlighted the characteristic of “self-control” and further suggested that the purpose-oriented and self-regulated attention in the moment is helpful in identifying internal and external resources. In another literature, “self-control” refers to the “capacity for altering one’s own responses, especially to bring them into line with standards such as ideals, values, morals, and social expectations, and to support the pursuit of long-term goals” (Baumeister et al. 2007, p. 351). Accordingly, individuals with a high level of Observing usually alter their attention to “ideals, values, morals, and social expectations,” such as character strengths and virtues. In the current study, Temperance Strength is the morally valued positive qualities shared by all human beings across cultures (Peterson and Seligman 2004). It describes the people who persist in achieving goals and exhibit self-control that connotes “goal-oriented,” “self-control,” and “hardworking” (Ho et al. 2014a). Thus, mindfulness and character strengths are naturally connected (Baer 2015).

Thornton et al. (2014) constructed a clinical intervention using a combination of mindfulness and hope components. The results are positive and imply that mindfulness skills are helpful in identifying personal hopeful thinking, which is likely to improve goal-setting and skills of goal achievement, and in improving mental health (Thornton et al. 2014). In addition, the “Strength Model of Self-control” further considers that regular exercises in self-control (e.g., self-regulated attention practice in mindfulness or meditation) can improve self-control (Baumeister et al. 2006). The abovementioned assumption is consistent with most of the existing intervention studies. For example, Thompson and Waltz (2007) found that everyday mindfulness practice positively enhances personal self-regulation. Another educational program also suggests that the mindfulness-based approach positively changes the level of the self-control of participants (Krasner et al. 2009). Therefore, the abovementioned discussion suggests that the Observing facet of mindfulness can be recognized to conceptually and empirically link with Temperance Strength characterized by self-control.

From the perspective of proposed mechanisms or models of mindfulness, these characteristics of Temperance Strength (e.g., self-regulated attention and goal-oriented attitude) are proposed as the core components underlying the mechanisms of mindfulness that enhance mental health (e.g., Baer 2003; Shapiro et al. 2006). In an early study, Baer (2003) preliminarily summarized the empirical findings from mindfulness-based interventions and recommended five possible mechanisms including exposure, change of cognition, self-management, relaxation, and acceptance, which can be helpful in practice. Shapiro et al. (2006) systematically proposed a three-factor model (Intention, Attention, and Attitude Model) based on the mindfulness practice in explaining the internal mechanism. Four mechanisms are specified, namely, self-regulation, flexibility, values clarification, and exposure (Shapiro et al. 2006); self-regulation is closely related to Temperance Strength in the three-dimensional model of character strengths. Grabovac et al. (2011) developed another model from the perspective of Buddhist psychology and suggested that “attention regulation” is the underlying factor of the reduction of clinical symptoms and the enhancement of wellbeing. In general, these theoretical models reflect the possible significances of Temperance Strength in understanding mindfulness. In other words, regulating the attention of individuals (i.e., Observing) to social expectations that support the pursuit of long-term goals (i.e., Temperance Strength) can improve mental wellbeing.

4 General Discussions

This study examined the relationship among three character strengths (i.e., Interpersonal Strength, Intellectual Strength, and Temperance Strength) and two facets of mindfulness (i.e., Observing and Non-judging) in affecting psychological wellbeing using a community sample and a college student sample. Cross-sectional (Study 1) and longitudinal (Study 2) designs were adopted. The results indicate that the Observing facet of mindfulness is positively related to the three character strengths, whereas the Non-judging facet of mindfulness is negatively related to them. The Observing facet of mindfulness cannot significantly predict Flourishing after entering the three character strengths. These results imply that the three character strengths and mindfulness can be treated as conceptually related but functionally distinct constructs. The results of the two studies also show that Temperance Strength mediates the relationship between Mindfulness and Flourishing. Participants with high Observing at Time 1 significantly predict their high Temperance Strength at Time 2, which in turn predicts high Flourishing at Time 3. These results partly elucidate the relationship between mindfulness and character strengths and suggest that Temperance Strength is a possible internal mechanism of mindfulness in affecting mental wellbeing.

Mindfulness was conceptualized to include two facets in the current study: “present-centered attention” (Observing) and “acceptance of internal experience” (Non-judging) (Coffey et al. 2010). In other words, mindfulness is a self-regulated attention or notice of the things that are happening and involves “taking a non-evaluative stance toward thoughts and feelings” (p. 330), including positive, negative, or neutral experiences (Baer et al. 2008; Creswell and Lindsay 2014). Mindfulness refers to the present-moment monitoring and non-judgmental acceptance of emotions and thoughts. In fact, the two facets of mindfulness, namely, attention (Observing) and attitude (Non-judging), are widely common and accepted for nearly all the definitions of mindfulness (Quaglia et al. 2014). Lilja et al. (2011) showed puzzling associations among Observing, Non-judging, and other psychological variables. As indicated by Baer et al. (2006), the Observing facet of mindfulness is particularly sensitive to changes in meditation experience, and the changes in the level of Observing may cause the changes in the relationships with other factors of mindfulness (e.g., Non-judging) and mental health outcomes.

For example, to examine the significance of Observing in all facets of mindfulness, Lilja et al. (2013) conducted cluster analysis among mediators (n = 325) and non-mediators (n = 317). The results revealed that, among the 13 clusters formed, the over-represented meditators always score high on the Observing subscale, and the under-represented meditators score low on it, suggesting that the level of mindfulness depends on the level of Observing (Lilja et al. 2013). However, the relationship between Observing and Non-judging is complicated. For example, the clusters indicate that some meditators with high levels of mindfulness, that is, high scores on Observing, have high scores on Non-judging, whereas some other meditators with high levels of mindfulness show very low scores on Non-judging. These contradicting results imply that the true relationship between Observing and Non-judging should be carefully examined. Actually, when constructing the FFMQ, Baer et al. (2006) also found that the correlation between the Observing facet and the Non-judging facet is insignificant (p. 36, Part 2). A possible explanation is that the methodology used to construct FFMQ mixes the dispositional and cultivated forms of mindfulness (Rau and Williams 2016). Duan and Li (2016) recently conducted a study on the item-level of FFMQ, which distinguished Observing facet as a dispositional component and Non-judging facet as a cultivated component. However, this conclusion must be further evaluated by other studies. For the second explanation, Teper et al. (2013) recognized present-moment attention and non-judgmental attitude as two stages with a sequence. The attention to sensation is involved in the first stage, and the non-judgmental attitude toward these sensations is promoted with the deepening of practice (i.e., mindfulness training or meditation) (Teper et al. 2013). As the participants involved in the current study were non-meditators, cultivating the non-judgmental attitude, which results in Observing being the only predictor of mental health outcome, is slightly difficult. Regardless of the complex associations between the Observing facet of mindfulness and other psychological variables, many findings imply that the essential facet of mindfulness should be Observing, which is self-regulated attention (Bishop et al. 2004; Lilja et al. 2013).

This study also highlights the importance of Temperance Strength. Coffey and Hartman (2008) proposed three mechanisms, namely, emotion regulation, reduced rumination, and nonattachment, to illustrate the benefits of mindfulness on psychological wellbeing. Emotion regulation refers to the ability to manage the effects, particularly the negative effects, such as adjusting cognitive thinking and alerting behaviors to address the source of distress. Reduced rumination is usually associated with the improvement of depression, which benefits mental health by removing attention from the repetitive and negative thoughts through mindful attention to the present moment. Attachment is the outcome that individuals attach to unattained goals, and individuals are more likely to ruminate when these important goals are not achieved. According to the abovementioned three mechanisms, Temperance Strength in the current character strength system, as characterized by self-regulation and self-control, is expected to work as a possible underlying mechanism in the mindfulness–mental health relationship. de Vibe et al. (2015) argued that conscientiousness characterized by self-regulation and self-control should be recognized as an important and interesting factor in mindfulness studies, as high conscientiousness predicts the increased effect of mindfulness intervention. Hamilton et al. (2006) also suggested that mindfulness practice can facilitate positive change and positive adjustment by strengthening metacognitive skills and by changing the pathway to emotion, health, and wellbeing.

Character strengths and mindfulness are conceptualized as dispositional qualities (Kabat-Zinn 1990; Park and Peterson 2009). In personality psychology, two approaches are used to define or understand personality, namely, the “having” approach and the “doing” approach (Cantor 1990). On the one hand, the “having” approach refers to stable patterns of thought, emotion, and action that are observed over time and across situations. Thus, Cantor (1990) recognized this kind of personality as something that individuals “have.” On the other hand, personality can also be referred to as the psychological processes and mechanisms that work behind adaptation through individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and actions. Using this point of view, Cantor (1990) recognized this kind of personality as something that individuals “do.” The two approaches are not completely independent, and most theories and models on personality reflect the having and doing views but have different emphases (Mischel and Shoda 1998). Based on these basic understandings, the current study suggests that character strengths and mindfulness reflect the “having” and “doing” views of personality or trait but have a different emphasis (Mischel and Shoda 1998). Character strengths reflect the stable patterns of thought, emotion, and action that are observed over time, whereas mindfulness reflects the psychological processes and mechanisms that work behind adaptation through individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and actions.

The results also show theoretical support for the newly developed intervention program “Mindfulness-Based Strengths Program (MBSP)” (Niemiec 2014). Basing on the findings of character strengths and mindfulness practices, practitioners and coaches have attempted to embed the two components of character strengths and mindfulness into an integrated intervention program “MBSP” to examine the combined effect. The eight-week MBSP was developed by the VIA Institute on Character to offer a systematic and integrative approach for practicing mindfulness and character strengths (Niemiec 2014). An important combination of MBSP is requiring participants to perceive their character strengths through mindfulness abilities, skills, and practices. Traditional mindfulness programs aim to manage stress, pain, depression, and anxiety, among others; on the contrary, MBSP uses mindfulness to explore, build, and enhance the good (i.e., strengths) in oneself and in others. Niemiec et al. (2012) suggested that this integration creates a beneficial relationship between strengths and mindfulness. This relationship can foster “a virtuous circle” in which mindful awareness facilitates strengths and consequently increases mental health. By using mindfulness, individuals can seriously and truly understand their strengths as well as focus their valued feelings and behaviors toward their goals. The initial pilot evaluation demonstrates that this combined approach is beneficial in reducing psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Niemiec 2014). Crescentini et al. (2014) found that mindfulness-oriented meditation can enhance the clarity of one’s thoughts and attitudes, which may be helpful in transforming implicit and explicit feelings into behaviors. However, no peer review publication evaluating the efficacy and exploring the internal mechanisms of MBSP can be identified in the current database (Baer 2015). The present study may shed light on the internal mechanism of MBSP that helps participants promote their mental health.

Some limitations must be mentioned for improvement in the future. First, although the Observing facet of mindfulness is identified as an essential facet in this study, the role of Non-judging, which is the other important facet of mindfulness in different definitions (Bishop et al. 2004; Coffey et al. 2010), remains unclear. The reason is that the participants involved in the current study were all non-meditators. Most Chinese do not have regular meditation experience. Baer et al. (2006) mentioned that mindfulness practice (e.g., meditation experience) is extremely important, regulating the relationships between the different facets of mindfulness (e.g., Observing and Non-judging), as well as their associations with mental health outcomes. More importantly, the non-judgmental attitude is gradually promoted with the deepening of meditation practice (Teper et al. 2013). Whether the experience of long-term meditation, a very important skill in mindfulness research and practice, will provoke the role of Non-judging needs to be explored among experienced meditators in future studies. Second, the well-educated college students involved in the longitudinal study limited the generalizability of the results to other populations. For example, whether the same longitudinal mediation model can be obtained among the samples with a history of depression remains unclear. Readers may also argue that Temperance Strength can possibly be more valued and important for college students, as strengths of goal achievement and self-control are important factors in this population. Accordingly, the results obtained in this study cannot be generalized to other specific samples. Therefore, a promising approach for the expansion of the findings of this study is to test whether at-risk populations, such as high-stress groups, chronic illness groups, or low-thriving groups (Duan et al. 2016), obtain higher levels of Observing than normal groups (e.g., low-stress group) through the same mindfulness training. Thereafter, Temperance Strength can be cultivated with the increased level of Observing and can result in improved mental wellbeing. Future studies can recruit populations from the clinic and the community to examine these results further. Third, all the researched variables in this project are self-reported. Future studies must use peer-rated and objective measurements to assess mindfulness, strengths, and mental health-related outcomes. However, additional evidence should be obtained before conclusions can be drawn. Experimental studies can be conducted to determine whether meditation can improve the Observing facet of mindfulness and change the Non-judging facet of mindfulness.

References

Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., et al. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: Impact of an online workplace intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(7), 721–731.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2000). Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychology and Health, 15(2), 173–189. doi:10.1080/08870440008400299.

Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., & Luthans, F. (2008). Can positive employees help positive organizational change? Impact of psychological capital and emotions on relevant attitudes and behaviors. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 44(1), 48–70. doi:10.1177/0021886307311470.

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bpg015.

Baer, R. A. (2015). Ethics, values, virtues, and character strengths in mindfulness-based interventions: A psychological science perspective. Mindfulness, 6(4), 956–969. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0419-2.

Baer, R. A., & Lykins, E. L. B. (2011). Mindfulness and positive psychological functioning. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Desiging positive psychology: Tanking stock and moving forward (pp. 335–348). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. doi:10.1177/1073191107313003.

Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality, 74(6), 1773–1802. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph077.

Boardman, S., & Doraiswamy, P. M. (2015). Integrating positive psychiatry into clinical practice. In D. V. Jeste & B. W. Palmer (Eds.), Positive psychiatry: A clinical handbook. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bowlin, S. L., & Baer, R. A. (2012). Relationships between mindfulness, self-control, and psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(3), 411–415. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.050.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Cantor, N. (1990). From thought to behavior: “Having” and “doing” in the study of personality and cognition. American Psychologist, 45(6), 730–735. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.6.735.

Carson, J. W., Carson, K. M., Gil, K. M., & Baucom, D. H. (2004). Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement. Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 471–494. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80028-5.

Chua, L. W., Milfont, T. L., & Jose, P. E. (2014). Coping skills help explain how future-oriented adolescents accrue greater well-being over time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0230-8.

Cioffi, D. (1991). Beyond attentional strategies: A cognitive-perceptual model of somatic interpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 109(1), 25–41. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.25.

Coffey, K. A., & Hartman, M. (2008). Mechanisms of action in the inverse relationship between mindfulness and psychological distress. Complementary Health Practice Review, 13(2), 79–91. doi:10.1177/1533210108316307.

Coffey, K. A., Hartman, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Deconstructing mindfulness and constructing mental health: Understanding mindfulness and its mechanisms of action. Mindfulness, 1(4), 235–253. doi:10.1007/s12671-010-0033-2.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558.

Colzato, L. S., Ozturk, A., & Hommel, B. (2012). Meditate to create: The impact of focused-attention and open-monitoring training on convergent and divergent thinking. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 116. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00116.

Crescentini, C., Urgesi, C., Campanella, F., Eleopra, R., & Fabbro, F. (2014). Effects of an 8-week meditation program on the implicit and explicit attitudes toward religious/spiritual self-representations. Consciousness and Cognition, 30, 266–280. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2014.09.013.

Creswell, J. D., & Lindsay, E. K. (2014). How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 401–407. doi:10.1177/0963721414547415.

Cruz, C., Navarro, E., Pocinho, R., & Ferreira, A. (2016). Happiness in advanced adulthood and the elderly: The role of positive emotions, flourishing and mindfulness as well-being factors for successful aging. Paper presented at the proceedings of the fourth international conference on technological ecosystems for enhancing multiculturality.

Dane, E., & Brummel, B. J. (2014). Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention. Human Relations, 67(1), 105–128. doi:10.1177/0018726713487753.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sørlie, T., et al. (2015). Does personality moderate the effects of mindfulness training for medical and psychology students? Mindfulness, 6(2), 281–289. doi:10.1007/s12671-013-0258-y.

Deng, Y.-Q., Liu, X.-H., Rodriguez, M. A., & Xia, C.-Y. (2011). The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness, 2(2), 123–128. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0050-9.

Didonna, F. (Ed.). (2009). Clinical handbook of mindfulness. New York, NY: Springer.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D.-W., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Duan, W. (2016a). The benefits of personal strengths in mental health of stressed students: A longitudinal investigation. Quality of Life Research, 25(11), 2879–2888. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1320-8.

Duan, W. (2016b). Mediation role of individual strengths in dispositional mindfulness and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 7–10. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.078.

Duan, W., Bai, Y., Tang, X., Siu, P. Y., Chan, R. K. H., & Ho, S. M. Y. (2012a). Virtues and positive mental health. Hong Kong Journal of Mental Health, 38(5), 24–31.

Duan, W., Guan, Y., & Gan, F. (2016). Brief inventory of thriving: A comprehensive measurement of wellbeing. Chinese Sociological Dialogue, 1(1), 15–31. doi:10.1177/2397200916665230.

Duan, W., & Guo, P. (2015). Association between virtues and posttraumatic growth: Preliminary evidence from a Chinese community sample after earthquake. PeerJ, 3, e883. doi:10.7717/peerj.883.

Duan, W., Guo, P., & Gan, P. (2015a). Relationships among trait resilience, virtues, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic growth. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0125707. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125707.

Duan, W., & Ho, S. M. Y. (2016). Three-dimensional model of strengths: Examination of invariance across gender, age, education levels, and marriage status. Community Mental Health Journal. doi:10.1007/s10597-016-0038-y.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Bai, Y., & Tang, X. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese virtues questionnaire. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(3), 336–345. doi:10.1177/1049731513477214.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Bai, Y., Tang, X., Zhang, Y., Li, T., et al. (2012b). Factor structure of the Chinese virtues questionnaire. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(6), 680–688. doi:10.1177/1049731512450074.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Siu, B. P. Y., Li, T., & Zhang, Y. (2015b). Role of virtues and perceived life stress in affecting psychological symptoms among chinese college students. Journal of American College Health, 63(1), 32–39. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.963109.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Tang, X., Li, T., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Character strength-based intervention to promote satisfaction with life in the Chinese university context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1347–1361. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9479-y.

Duan, W., & Li, J. (2016). Distinguishing dispositional and cultivated forms of mindfulness: item-level factor analysis of five-facet mindfulness questionnaire and construction of short inventory of mindfulness capability. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1348. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01348.

Duan, W., & Xie, D. (2016). Measuring adolescent flourishing: Psychometric properties of flourishing scale in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. doi:10.1177/0734282916655504.

Duggan, K. A., Friedman, H. S., McDevitt, E. A., & Mednick, S. C. (2014). Personality and healthy sleep: The importance of conscientiousness and neuroticism. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e90628. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090628.

Gallagher, M., Prinstein, M. J., Simon, V., & Spirito, A. (2014). Social anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation in a clinical sample of early adolescents: Examining loneliness and social support as longitudinal mediators. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(6), 871–883. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9844-7.

Grabovac, A. D., Lau, M. A., & Willett, B. R. (2011). Mechanisms of mindfulness: A Buddhist psychological model. Mindfulness, 2(3), 154–166. doi:10.1007/s12671-011-0054-5.

Hamilton, N. A., Kitzman, H., & Guyotte, S. (2006). Enhancing health and emotion: Mindfulness as a missing link between cognitive therapy and positive psychology. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 123–134. doi:10.1891/jcop.20.2.123.

Harris, A. R., Jennings, P. A., Katz, D. A., Abenavoli, R. M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2016). Promoting stress management and wellbeing in educators: Feasibility and efficacy of a school-based yoga and mindfulness intervention. Mindfulness, 7(1), 143–154.

Ho, S. M. Y., Duan, W., & Tang, S. C. M. (2014a). The psychology of virtue and happiness in western and asian thought. In N. E. Snow & F. V. Trivigno (Eds.), The philosophy and psychology of character and happiness (pp. 215–238). New York: Routledge.

Ho, S. M. Y., Li, W. L., Duan, W., Siu, B. P. Y., Yau, S., Yeung, G., et al. (2016). A brief strengths scale for individuals with mental health issues. Psychological Assessment, 28(2), 147–157. doi:10.1037/pas0000164.

Ho, S. M. Y., Rochelle, T. L. R., Law, L. S. C., Duan, W., Bai, Y., Shih, S.-M., et al. (2014b). Methodological issues in positive psychology research with diverse populations: Exploring strengths among Chinese adults. In J. T. Pedrotti & L. M. Edwards (Eds.), Perspectives on the intersection of multiculturalism and positive psychology (pp. 45–57). New York, NY: Springer.

Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. doi:10.1037/a0031313.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. NewYork, NY: Bantam Dell.

Krasner, M. S., Epstein, R. M., Beckman, H., Suchman, A. L., Chapman, B., Mooney, C. J., et al. (2009). Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA, 302(12), 1284–1293. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1384.

Lakey, C. E., Kernis, M. H., Heppner, W. L., & Lance, C. E. (2008). Individual differences in authenticity and mindfulness as predictors of verbal defensiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.05.002.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., et al. (2006). The Toronto mindfulness scale: development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467. doi:10.1002/jclp.20326.

Lilja, J. L., Frodi-Lundgren, A., Hanse, J. J., Josefsson, T., Lundh, L.-G., Sköld, C., et al. (2011). Five facets mindfulness questionnaire—Reliability and factor structure: A Swedish version. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(4), 291–303. doi:10.1080/16506073.2011.580367.

Lilja, J. L., Lundh, L.-G., Josefsson, T., & Falkenström, F. (2013). Observing as an essential facet of mindfulness: A comparison of FFMQ patterns in meditating and non-meditating individuals. Mindfulness, 4(3), 203–212. doi:10.1007/s12671-012-0111-8.

Malinowski, P., & Hui, J. L. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Positive affect, hope, and optimism mediate the relationship between dispositional mindfulness, work engagement, and well-being. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1250–1262. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0388-5.

McGrath, R. E. (2015). Integrating psychological and cultural perspectives on virtue: The hierarchical structure of character strengths. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 407–424. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.994222.

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1998). Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 229–258.

Mitchell, J. T., Zylowska, L., & Kollins, S. H. (2015). Mindfulness meditation training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: Current empirical support, treatment overview, and future directions. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(2), 172–191. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.10.002.

Niemiec, R. M. (2014). Mindfulness and character strengths: A practical guide to flourishing. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe.

Niemiec, R. M., Rashid, T., & Spinella, M. (2012). Strong mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness and character strengths. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(3), 240.

Olsen, S. O., Tuu, H. H., Honkanen, P., & Verplanken, B. (2015). Conscientiousness and (un) healthy eating: The role of impulsive eating and age in the consumption of daily main meals. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. doi:10.1111/sjop.12220.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Character strengths research and practice. Journal of College and Character, 10(4), 1–10.

Parks, A. C., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). Positive interventions: Past, present and future. In T. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Bridging acceptance and commitment therapy and positive psychology: A practitioner’s guide to a unifying framework. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Peters, J. R., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., & Smart, L. M. (2015). Dispositional mindfulness and rejection sensitivity: The critical role of nonjudgment. Personality and Individual Differences. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.029.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2015). Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term effects for a signature strengths-vs. a lesser strengths-intervention. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456.

Quaglia, J. T., Brown, K. W., Lindsay, E. K., Creswell, J. D., & Goodman, R. J. (2014). From conceptualization to operationalization of mindfulness. In K. W. Brown, J. D. Creswell, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building on what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1145–1163. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9311-5.

Rau, H. K., & Williams, P. G. (2016). Dispositional mindfulness: A critical review of construct validation research. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 32–43. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.035.

Roche, M., Haar, J. M., & Luthans, F. (2014). The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(4), 476–489. doi:10.1037/a0037183.

Schmertz, S. K., Masuda, A., & Anderson, P. L. (2012). Cognitive processes mediate the relation between mindfulness and social anxiety within a clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 362–371.

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. doi:10.1002/jclp.20237.

Short, M. M., Mazmanian, D., Oinonen, K., & Mushquash, C. J. (2016). Executive function and self-regulation mediate dispositional mindfulness and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.007.

Shryack, J., Steger, M. F., Krueger, R. F., & Kallie, C. S. (2010). The structure of virtue: An empirical investigation of the dimensionality of the virtues in action inventory of strengths. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(6), 714–719. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.007.

Smith, T. W., & Gallo, L. C. (2001). Personality traits as risk factors for physical illness. In A. Baum, T. Revenson, & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology (pp. 139–172). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Smith, T. W., & Ruiz, J. M. (2004). Personality theory and research in the study of health and behavior. In T. J. Boll, R. G. Frank, A. Baum, & J. L. Wallander (Eds.), Handbook of clinical health psychology. Models and perspectives in health psychology (pp. 143–199). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Stone, G. C., Cohen, F., & Adler, N. E. (1980). Health psychology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Szekeres, R. A., & Wertheim, E. H. (2014). Evaluation of vipassana meditation course effects on subjective stress, well-being, self-kindness and mindfulness in a community sample: Post-course and 6-month outcomes. Stress and Health. doi:10.1002/smi.2562.

Tang, X., Duan, W., Wang, Z., & Liu, T. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of the simplified Chinese version of flourishing scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(5), 591–599. doi:10.1177/1049731514557832.

Teper, R., Segal, Z. V., & Inzlicht, M. (2013). Inside the mindful mind: How mindfulness enhances emotion regulation through improvements in executive control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(6), 449–454. doi:10.1177/0963721413495869.

Thompson, B. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personality and Individual Differences, 43(7), 1875–1885. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.017.

Thornton, L. M., Cheavens, J. S., Heitzmann, C. A., Dorfman, C. S., Wu, S. M., & Andersen, B. L. (2014). Test of mindfulness and hope components in a psychological intervention for women with cancer recurrence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1087–1100. doi:10.1037/a0036959.

Truijens, S. E. M., Nyklíček, I., van Son, J., & Pop, V. J. M. (2015). Validation of a short form three facet mindfulness questionnaire (TFMQ-SF) in pregnant women. Personality and Individual Differences. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.037.

Vinci, C., Spears, C. A., Peltier, M. K. R., & Copeland, A. L. (2016). Drinking motives mediate the relationship between facets of mindfulness and problematic alcohol use. Mindfulness, 7(3), 754–763. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0515-y.

Walach, H., Nord, E., Zier, C., Dietz-Waschkowski, B., Kersig, S., & Schüpbach, H. (2007). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a method for personnel development: A pilot evaluation. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 188–198. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.188.

Xu, W., Oei, T. P., Liu, X., Wang, X., & Ding, C. (2014). The moderating and mediating roles of self-acceptance and tolerance to others in the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Journal of Health Psychology. doi:10.1177/1359105314555170.

Zeidner, M., Roberts, R. D., & Matthews, G. (2008). The science of emotional intelligence. European Psychologist, 13(1), 64–78. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00381.x.

Zhang, Y., Yang, Z., Duan, W., Tang, X., Gan, F., Wang, F., et al. (2014). A preliminary investigation on the relationship between virtues and pathological internet use among Chinese adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8(1), 8. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-8-8.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Wuhan University Humanities and Social Sciences Academic Development Program for Young Scholars “Sociology of Happiness and Positive Education”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, W., Ho, S.M.Y. Does Being Mindful of Your Character Strengths Enhance Psychological Wellbeing? A Longitudinal Mediation Analysis. J Happiness Stud 19, 1045–1066 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9864-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9864-z