Abstract

In this chapter, we provide an overview and critical examination of published research concerning the impact of religious involvement on the outcomes of sexuality and sexual health across the life course. We take a broad approach, focusing on a variety of important topics, including sexual behavior, sexual health education, abortion attitudes and behavior, HIV/AIDS, attitudes toward gays and lesbians, and the lived experiences of sexual minorities. In the future, researchers should (1) employ more comprehensive measures of religious involvement, (2) investigate understudied outcomes related to sexuality and sexual health, (3) explore mechanisms linking religion, sexuality, and sexual health, (4) establish subgroup variations in the impact of religious involvement, and (5) formally test alternative explanations like personality selection and social desirability. Research along these lines would certainly contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of religious variations in sexuality and sexual health across the life course.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Religious involvement—indicated by observable feelings, beliefs, activities, and experiences in relation to spiritual, divine, or supernatural entities—is a prevalent and powerful socio-cultural force in the lives of many Americans. According to national estimates from a recent Gallup poll (2013), a large percentage of U.S. adults continue to affiliate with a religious group (83 %). Approximately eight-in-ten U.S. adults report affiliating with a Christian religious organization, while about 5 % belong to other faiths. Roughly one-in-six are not affiliated with a religious group. Within Christianity, about half (51.8 %) of the U.S. population is Protestant. U.S. Protestants can be divided into three distinct traditions: conservative or evangelical Protestants (roughly one-half of all Protestants, or 26 % of the adult population), mainline Protestants (18 % of the population), and members of historically African American Protestant churches (approximately 7 % of the population). Catholics comprise almost one-quarter (23.9 %) of the U.S. population. Other Christian denominations are much smaller. For example, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and other Mormon groups make up less than 2 % of the adult population (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2008).

These patterns are remarkable on their own, but they also all raise numerous questions concerning the outcomes of religious involvement in everyday life. In this chapter, we provide an overview and critical examination of published research concerning the impact of religious involvement on the outcomes of sexuality and sexual health across the life course. In the pages that follow, we take a broad approach, focusing on a variety of important topics, including sexual behavior, sexual health education, abortion attitudes and behavior, HIV/AIDS, attitudes toward gays and lesbians, and the lived experiences of sexual minorities. Although we draw heavily from research conducted by sociologists, we note several significant contributions by scholars in religious studies, public health, psychology, and child development. We also primarily focus on the U.S. context, but we describe important research conducted in other countries when appropriate. Given the religious make-up of the United States, most of the studies discussed in this review focus on the influence of Christianity on sexuality and sexual health.

2 Religion and Sexual Behavior

Researchers have linked various indicators of religious involvement and a range of sexual behaviors across the life course, from adolescence (Burdette and Hill 2009; Regnerus 2007; Rostosky et al. 2004) and young adulthood (Adamczyk and Felson 2008; Davidson et al. 2004; Vazsonyi and Jenkins 2010) to adulthood (Barkan 2006; Gillum and Holt 2010) and late life (McFarland et al. 2011). Religion appears to influence both attitudes toward sexual activity and sexual behavior.

Scholars have long noted that U.S. residents who are members of conservative religious communities (e.g., Southern Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Mormons) (Gay et al. 1996; Petersen and Donnenwerth 1997), those who hold a literalist interpretation of the Bible (Ogland and Bartkowski 2014), and those who display higher levels of religious involvement (Cochran and Beeghley 1991; Ellison et al. 2013) tend to have more conservative sex-related attitudes (e.g., toward premarital sex, extramarital sexual behavior, and homosexuality) than other individuals in the United States. Cross-national studies show that Muslims and Hindus tend to hold more conservative attitudes toward sex than do Christians (Finke and Adamczyk 2008). Evidence also suggests that Jews tend to have more liberal sex-related attitudes than Christians (Regnerus and Uecker 2007). Research examining the sex-related attitudes of Buddhists has yielded inconsistent results (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009; Finke and Adamczyk 2008; De Visser et al. 2007).

2.1 Religion and Adolescent Sexual Behavior

Of all of the research on the connection between religion and sexual behavior, perhaps the most scholarly attention has been devoted to understanding the relationship between religious involvement and heterosexual adolescent sexual activity. Research consistently shows that religious involvement, often conceptualized as church attendance , is associated with delayed initiation of sexual intercourse (Regnerus 2007; Meier 2003; Rostosky et al. 2004) and fewer sexual partners (Miller and Gur 2002; Thornton and Camburn 1989) in adolescence. More limited evidence suggests that religiosity is associated with postponement of other types of sexual activity as well, including oral sexual behavior and genital touching (Burdette and Hill 2009; Hull et al. 2011; Regnerus 2007).

Researchers have also noted important variations in adolescent sexual behavior by religious affiliation . Some studies show that adolescents who are affiliated with conservative religious groups (e.g. Mormons, evangelicals, and fundamentalists) are more likely to delay sexual intercourse than their mainline or unaffiliated peers (Beck et al. 1991; Brewster et al. 1998). Other research suggests that adolescents who identify with evangelical Protestant denominations (e.g., Southern Baptists, Pentecostal, and Church of God) are actually less likely to delay sexual intercourse than are mainline and Jewish adolescents (Regnerus 2007). In general, the effects of religious affiliation on sexual behavior are weaker than those of religious involvement. This suggests that degree of involvement matters more than simply identifying with a particular religious group.

Why might religious involvement be associated with delayed sexual activity in adolescence? Various aspects of religiosity may influence teen sexual activity in different, but reinforcing, ways. Church attendance might reduce or delay sexual activity by exposing adolescents to messages and norms concerning sexual morality. Indeed, studies indicate that attitudes about sexual behavior are an important mechanism linking religion and sexual activity (Meier 2003; Rostosky et al. 2003). Religious attendance may also embed adolescents within sexually conservative contexts, where parental monitoring is high (Smith 2003a, b) and informal social sanctions are regularly enforced against persons suspected of non-marital sexual activity (Thornton and Camburn 1989; Adamczyk and Felson 2006). While frequency of church attendance indicates exposure to moral messages, religious salience, or how important religion is to the individual, may indicate the degree to which these messages have been internalized (Rohrbaugh and Jessor 1975). Like church attendance, private religiosity indicates exposure to religious doctrines and reinforces religious teachings in the areas of obedience, self-control, and sexual morality (Smith 2003b).

In addition to personal religiosity, research suggests that both parental religiosity and peer religiosity can influence adolescent sexual behavior. Evidence suggests that parental religiosity is associated with delayed sexual initiation (Manlove et al. 2006) and reduced sexual risk taking (Landor et al. 2011). Similarly, Adamczyk and Felson (2006) find that friends’ religiosity has an independent influence on adolescent sexual behavior that is similar in magnitude to personal religiosity. They argue that friends’ religious involvement reduces adolescent sexual activity through opportunity limitations, reputational costs, and pro-virginity normative influences. Teens with more religious friends may have more difficulty finding a partner who is or could be sexually active than adolescents embedded in more secular social networks. Losing one’s virginity may be a status gain among secular friends, but adolescents with religious friends may lose status by having sexual intercourse (Adamczyk and Felson 2006). More recent work by Adamczyk (2009a) suggests that selection effects may explain part of the link between friends’ religiosity and adolescent sexual debut, as teens who delay first intercourse tend to switch to more religious friends while those who have had sexual intercourse tend to switch to less religious friends.

2.2 Religion and Adolescent Contraceptive Use

While religious involvement is generally protective of adolescent sexual behavior, associations with contraceptive use are more precarious and sometimes counterproductive. Some evidence indicates that those adolescents who are most likely to delay sexual intercourse (i.e., fundamentalist Protestants) are the least likely to use contraception when they do transition to first sex (Cooksey et al. 1996; Kramer et al. 2007); however, other research finds no association between religious affiliation and contraceptive use (Brewster et al. 1998). There is little evidence that religious attendance (Brewster et al. 1998; Kramer et al. 2007) or religious salience (Kramer and Dunlop 2012) impact adolescent contraceptive use. Parental religiosity may also negatively impact adolescent contraceptive use by limiting information about birth control. Evidence suggests that both parental public religious involvement and parental religious salience reduce the frequency of conversations with adolescent children about sex and birth control. When religiously devout parents do talk to their teen children about sexual behavior, they often focus on morality, not on conveying information about contraception (Regnerus 2005).

2.3 The Virginity Pledge Movement

Beginning in 1993, the Southern Baptist Church sponsored a movement to encourage adolescents to take public virginity pledges in which they vow to abstain from sex until marriage. Since this time, other conservative Christian organizations have spearheaded efforts to promote sexual abstinence among unmarried adolescents and young adults (Carpenter 2011). Research suggests that pledging is most common among evangelical and Mormon youth and rare among Jewish and non-religious teens. Pledging is also more common among adolescents who attend church frequently than among those who attend less often (Regnerus 2007). In their seminal work on the pledge movement, Bearman and Brückner (2001) find that pledgers are much more likely to delay sexual intercourse than adolescents who do not pledge. However, those pledgers who break their promise of abstinence are less likely to use contraception at first intercourse, a finding that is consistent with more recent research on this topic (Manlove et al. 2003; Rosenbaum 2009). Bearman and Brückner explain that pledgers are less likely to be prepared for an experience that they have promised to avoid. The authors argue that being “contraceptively prepared” may be psychologically distressing for teens who have publicly vowed to abstain from sexual intercourse until marriage. In follow up work, these scholars show that the rate of sexually transmitted infections is similar for pledgers and non-pledgers (Brückner and Bearman 2005).

2.4 Subgroup Variations in the Relationship Between Religion and Sexual Behavior

Is the association between religious involvement and sexual activity the same for all adolescents? Studies consistently show that religious involvement is more strongly associated with the sexual behavior of females than males (Burdette et al. 2005; Regnerus 2007; Rostosky et al. 2004). Although boys and girls may be encouraged to refrain from sexual activities, virginity status may be especially important for girls. For example, the sexual status of females is often noted within Biblical texts, yet is rarely mentioned for male figures (e.g. Lev. 21:7; Luke 1:34; John 4:17–19).

Some evidence suggests that the association between religious involvement and delayed sexual activity is weaker for African American adolescents than among Whites adolescents (Bearman and Brückner 2001); however, other research finds consistent effects across racial groups (Rostosky et al. 2004). Scholars speculate that Black churches may be more forgiving of sexual transgressions than are predominately White churches (Hertel and Hughes 1987; Lincoln and Mamiya 1990). To this point, it is unclear in the literature how the association between religion and adolescent sexual behavior might vary between non-Hispanic White and Hispanic adolescents. Limited evidence suggests that religiosity reduces sexual activity among Latinas, particularly those of Mexican origin (Edwards et al. 2011).

Few scholars have examined variations in the impact of religiosity on adolescent sexual behavior by sexual identity. In fact, little research has examined the influence of religion on adolescent sexual activity among sexual minority youths . In one important exception to this general trend, Hatzenbuehler et al. (2012) show that living in a county with a religious climate that is supportive of homosexuality is associated with fewer sexual partners for teens identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Although their results also suggest that the impact of religious climate on sexual behavior is stronger among sexual minority youth than heterosexual teens, additional research is needed to confirm these findings.

2.5 Religion and Young Adult Sexual Behavior

While scholars have devoted more attention to examining the relationship between religion and sexual behavior in adolescence than any other stage in the life course, a modest amount of research has examined this association in young adulthood, especially among college students. Understanding the influence of religion on sexual health among emerging adults is important because many Americans exhibit a decline in religious involvement (principally religious attendance) during this stage of life. Although scholars have speculated that this religious decline is due to the secularizing effects of higher education, evidence suggests that emerging adults who do not attend college exhibit the most extensive patterns of religious decline, thus contradicting the conventional wisdom (Uecker et al. 2007).

In general, religion continues to be protective in delaying or reducing sexual activity during young adulthood, including sexual risk taking. Scholarship suggests that religious young adults are more likely to delay (Adamczyk and Felson 2008; Davidson et al. 2004; Vazsonyi and Jenkins 2010) or forgo (Uecker 2008) premarital sex than their non-religious peers. Findings on the impact of religious involvement on the number of sexual partners are more mixed. While some research suggests that religiosity is associated with fewer sexual partners among female undergraduates (Davidson et al. 2004), other work finds no effects for either religious affiliation or participation among young women (Jones et al. 2005).

As changing norms in the dating and sexual behaviors of college students have captured scholarly and media attention (Haley et al. 2001; England et al. 2007), a relatively new line of research explores the connection between religion and “hooking up” among college students. Although somewhat ambiguous in meaning, students generally use the term “hooking up” to refer to a physical encounter between two people who are largely unfamiliar with one another or otherwise briefly acquainted (Glenn and Marquardt 2001). A typical hook-up involves moderate to heavy alcohol consumption (a median of four drinks for women and six for men) and carries no anticipation of a future relationship (England et al. 2007).

Research suggests that church attendance is associated with reduced odds of hooking up (Burdette and Hill 2009) and fewer hook-ups (Brimeyer and Smith 2012) while in college. Limited scholarship also suggests that Catholics display higher rates of hooking up compared to conservative Protestants (Brimeyer and Smith 2012) and those students with no religious affiliation (Burdette and Hill 2009). Burdette et al. (2009) also find that women who attend colleges and universities with a Catholic affiliation are more likely to have hooked up while at school than women who attend academic institutions with no religious affiliation, net of individual-level religious involvement. Other work by Freitas (2008) shows that the influence of religion on casual sexual behavior is limited to those attending evangelical colleges and universities.

While research on hooking up suggests that religious involvement may be a protective force in the lives of young adults, research on contraceptive use among this age group suggests otherwise. In their study of unmarried young adults, Burdette et al. (2014) show that evangelical Protestants are more likely to exhibit inconsistent contraception use than those with no religious affiliation. These scholars also show that conservative Protestants are more likely to hold misconceptions about their own fertility than non-affiliates, suggesting that this group may have limited access to accurate information concerning sexual health. Other research suggests that young women who frequently attend religious services are less likely to use sexual and reproductive health services (i.e., routine gynecologic examination care, sexually transmitted infection testing/treatment, and services for contraception) than young women who attend church less frequently, despite sexual experience (Hall et al. 2012). Taken together, findings from these studies suggest an unmet need for sexual and reproductive health care among religiously active women, particularly those who identify with conservative religious faiths.

2.6 Religion and Sexual Behavior in Adulthood

While a number of studies have examined the association between religion and sex-related attitudes among U.S. adults, fewer studies have investigated the relationship between religion and sexual behavior in adulthood. Using pooled data from the General Social Survey (1993–2002), Barkan (2006) shows an inverse association between religiosity and number of sexual partners among never-married adults. Further analysis of subgroup variations shows similar effects for both men and women, but differing effects by race. While religiosity is inversely related to number of partners among Whites, it is unrelated to number of sexual partners among African Americans. Other research examining sexual risk-taking behaviors (e.g., women with male partners who have had sex with other males and having a sexual partner who is an intravenous drug user) suggests that church attendance is protective against sexual risk-taking for women. Among men, members of fundamentalist, non-denominational Protestant and other non-Christian denominations tend to exhibit more sexual risk factors than members of mainline Christian denominations (Gillum and Holt 2010).

A few studies have examined the link between religion and adult sexual behavior among non-Christian groups. This research suggests that Muslims are less likely than Christians to have had premarital sex (Addai 2000; Agha 2009). Using cross-national data, Adamczyk and Hayes (2012) investigate how identifying with one of the major world religions (i.e., Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, or Judaism) and living in a nation with a Muslim culture can impact sexual behavior outside of marriage. Their results show that ever married Hindus and Muslims are less likely to report having had premarital sex than are ever married Jews and Christians. Furthermore, the percentage of Muslims within a nation is associated with fewer reports of premarital sex.

In addition to research examining the link between religion and premarital sexual behavior in adulthood, several studies have examined the relationship between religious involvement and marital infidelity. In these studies, marital infidelity is typically defined as having had sexual intercourse with someone other than one’s spouse during the course of the marriage. This definition is somewhat limited—excluding other forms of infidelity—but including couples who have an “open” relationship which includes a negotiated agreement to allow nonmonogamy. This line of research suggests that frequent religious attendance reduces the odds of marital infidelity among U.S. adults (Burdette et al. 2007; Atkins and Kessel 2008). Public religious participation is a potential source of control over marital sexuality because connections to friends and family forged through regular interactions in religious settings may reduce opportunities for extramarital sex and raise the likelihood and costs of detection. There is also some evidence of variations in marital infidelity by religious affiliation . Burdette et al. (2007) find that with the exception of two religious groups (nontraditional conservatives and non-Christian faiths), holding any religious affiliation is associated with reduced odds of marital infidelity compared to those with no religious affiliation. This work also suggests that holding more conservative Biblical beliefs is associated with reduced odds of infidelity. Cross-national research suggests that Muslims are less likely than Hindus, Christians, and Jews to engage in marital infidelity (Adamczyk and Hayes 2012).

The few studies that have examined the relationship between religion and contraceptive use among adults suggest modest differences in contraception decision making by religious affiliation . Drawing on data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), Jones and Dreweke (2011) find that among women who have been sexually active, 99 % have used a contraceptive method other than natural family planning. This figure is virtually identical for sexually experienced Catholic women (98 %), despite opposition from Catholic hierarchy, who only approve of “natural” family planning methods for married couples (e.g., periodic abstinence, temperature and cervical mucus tests). In contrast, evidence suggests that most evangelical Protestant leaders and church members approve of the use of contraception, including sterilization, for married women (Barrick 2010). Findings also show that Protestants are more likely than Catholics to use highly effective contraceptive methods, such as sterilization, hormonal methods, or intrauterine devices (IUDs). Attendance at religious services and religious salience appear to be unrelated to choice of contraceptive method (Jones and Dreweke 2011).

Along with studying the influence of religiosity on personal contraceptive use, scholars have explored other interesting connections between religion and contraception. While few U.S. obstetrician-gynecologists have moral or ethical problems with modern contraceptive methods (only 5 % report objecting to one or more methods), doctors who report high levels of religious salience and those with frequent religious participation are more likely than their less religious counterparts to refuse to offer specific contraceptives (Rosenberg 2011). Similarly, religion is an important predictor of pharmacists’ willingness to dispense emergency contraception and medical abortifacients. In their study of Nevada pharmacists, Davidson et al. (2010) show that evangelical Protestants and Catholics are significantly more likely to refuse to dispense at least one medication in comparison to pharmacists with no religious affiliation. Work by these scholars illuminates the influence of religion on healthcare workers who may be given leeway to consider morality and value systems when making clinical decisions about care. Policymakers should consider policies that balance the rights of patients, physicians, and pharmacists alike (Davidson et al. 2010).

2.7 Religion and Sexual Behavior in Later Life

The relationship between religion and sexual behavior in later life is virtually unexamined. In one important exception to this general trend, McFarland et al. (2011) investigate the influence of religion on the sex lives of married and unmarried community dwelling older adults (ages 57–85). Using nationally representative data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, they find that religion is largely unrelated to sexual frequency and satisfaction among married older adults. However, among unmarried adults, religious integration in daily life exhibits a negative association with having had sex in the last year among women, but not among men.

3 Religion and Sexual Health Education

Social scientists are interested in the connection between religion and sexual health education primarily due to the success of religious conservatives in implementing abstinence-only sex education in public schools. According to Williams (2011), “the role of evangelical Christianity in the abstinence movement cannot be overstated.” Throughout the movement, conservative Christian organizations have been key players in the passage of abstinence education policy and continue to defend abstinence-only education at the local, state, and federal level. While health officials generally view sexual abstinence as a behavioral issue, the majority of advocates of abstinence-only education programs are focused on issues of morality (Santelli et al. 2006). Sexual health education programs continue to define abstinence within the context of Christianity, often referencing Biblical notions of purity and heterosexual marriage (Williams 2011).

Before discussing current connections, it is important to provide a brief history of the connection between the Christian Right and sexual health education. Sex education emerged as an important issue to religious conservatives during the 1970s as part of an overall agenda to combat what they viewed as a decline in sexual morality (Williams 2011). During this time period, the primary goal of the movement was to remove any form of sex education from public schools, as the Christian Right viewed sex education as an attempt by liberals to undermine parental authority and Christian mortality by promoting liberal sexual mores like premarital sexual behavior, abortion, homosexuality, and pornography (McKeegan 1992). By the 1980s, it became clear to religious conservatives that removing any discussion of sexual health from public schools was a losing battle. Rather than accept defeat, conservative Christian groups changed strategies, focusing on restructuring the content of sex education . Grass-roots support was provided by groups like the Eagle Forum, Concerned Women for America, Focus on the Family, and Citizens for Excellence in Education, all of whom devoted major resources to promoting abstinence-only programs as an alternative to comprehensive sexual health education (Rose 2005; Williams 2011) .

During the 1990s, the campaign led by religious conservatives to promote abstinence-only education began to achieve considerable political success, and funding for these programs grew exponentially under the George W. Bush administration. From 1996 to 2005, over 1 billion state and federal dollars were allocated to abstinence only sex education programs (Rose 2005). In 1996, the US Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the high profile welfare reform bill. PRWORA included a $ 250 million grant for abstinence-only programs (referred to as Title V funding), ushering in the heyday of this form of sex education (Williams 2011; Arsneault 2001). The passage of Title V included a formal definition of abstinence—the A-H criteria—that all federally funded abstinence programs were required to follow. Under Sect. 510 of the 1996 Social Security Act, abstinence education is defined as an educational or motivational program which teaches (A) the social, psychological, and health gains to be realized by abstaining from sexual activity; (B) abstinence from sexual activity outside marriage as the expected standard for all school-age children; (C) that abstinence from sexual activity is the only certain way to avoid out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and other associated health problems; (D) that a mutually faithful monogamous relationship in the context of marriage is the expected standard of human sexual activity; (E) that sexual activity outside of the context of marriage is likely to have harmful psychological and physical effects; (F) that bearing children out-of-wedlock is likely to have harmful consequences for the child, the child’s parents, and society; (G) young people how to reject sexual advances and how alcohol and drug use increases vulnerability to sexual advances; (H) the importance of attaining self-sufficiency before engaging in sexual activity (Santelli et al. 2006). Title V authorized $ 50 million annually from 1998 through 2002 for abstinence-only education. Regular extensions from 2002 maintained funding levels until 2010, when program funding was incorporated into the health care reform law in an effort to promote bipartisan support for the bill (Williams 2011; Doan and McFarlane 2012). However, federal funding for abstinence-only education has declined significantly. The Obama administration provides federal funds supporting both comprehensive sex education and abstinence-only education. States have the option of applying for either program or both programs (SIECUS 2012).

It is important to note that even during the time period when abstinence-only sexual health education was widespread, with roughly one-third of public school districts teaching an abstinence-only curriculum (Landry et al. 2003), a number of states declined federal funding for these programs. Initially, only California declined the funding provided by Title V after determining abstinence-only programs were ineffective (Raymond et al., 2008). However, by 2009, 24 additional states had rejected funds for abstinence-only education. Evidence suggests that a change in governor partisanship from a Republican to a Democrat, a high percentage of politically liberal residents, and a higher per capita state income are all associated with increased odds of declining federal funding for abstinence-only education (Doan and McFarlane 2012).

Researchers and public health officials have raised several concerns with abstinence-only sexual health curricula . First, the overwhelming majority of Americans do not remain sexually abstinent until marriage. Most individuals will have sexual intercourse for the first time during their teens (Martinez et al. 2011); however, the current average age at first marriage is roughly 26-years-old for women and 28-years-old for men in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). This suggests that the majority of heterosexual individuals are sexually active for almost a decade before getting married. Further, roughly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, a rate that is higher for young adults than for any other age group (Finer and Henshaw 2006). Taken together, these facts suggest that teens and young adults benefit from information about effective methods of contraception (Finer and Philbin forthcoming).

Second, there is little evidence that abstinence-only education delays teen sexual activity, and some research indicates that it may deter contraceptive use among sexually active teens (Santelli et al. 2006; Boonstra 2010). Findings from a 2004 congressional report indicate that 11 out of the 13 abstinence-only programs evaluated contained inaccurate information about contraceptive effectiveness and the risks of abortion. These curricula also tended to treat stereotypes about girls and boys as scientific fact and blur religious and scientific information (United States House of Representatives 2004). Santelli et al. (2006) note that governmental failure to provide accurate information about contraception raises serious ethical concerns given that access to complete and accurate sexual health information has been recognized as a basic human right. Abstinence-only education is likely to be particularly detrimental to the well-being of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youths given that classes are unlikely to meet their health needs and often stigmatize homosexuality as deviant behavior (Santelli et al. 2006).

Finally, scholars have noted that abstinence-only education policies are generally unsupported by U.S. adults. Using a random sample of U.S. adults, Bleakley et al. (2006) show that approximately 82 % of respondents support programs that include abstinence and other methods of preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. In contrast, abstinence-only education received the lowest levels of support (36 %) and the highest levels of opposition. Evidence suggests that comprehensive sex education is supported by even the most religiously involved Americans, albeit at lower levels than their less religious counterparts (Bleakley et al. 2006; Luker 2006).

4 Religion and Abortion

4.1 Religion and Abortion Attitudes

A long line of research has consistently linked religion with opinions about the morality and legality of abortion. In their review of the literature, Jelen and Wilcox (2003) determined that religion is one of the strongest predictors of abortion attitudes. Overall, studies suggest that conservative Protestants are more likely than other individuals to hold pro-life attitudes, followed by Catholics and mainline Protestants. Conversely, pro-choice views are most prevalent among Jews and those with no religious affiliation (Cook et al. 1992; Ellison et al. 2005; Hertel and Hughes 1987). Evidence also suggests that there is little variability in attitudes toward abortion among conservative Protestants when compared to members of other religious groups (Hoffmann and Johnson 2005; Hoffmann and Miller 1997, 1998). Further, abortion is one of the few sex-related attitudes for which there is little indication of liberalization among younger generations (Farrell 2011; Smith and Johnson 2010). Drawing on national data, Farrell (2011) finds that younger evangelicals hold more liberal attitudes on same-sex marriage, premarital sex, cohabitating, and pornography , but not abortion, than their older evangelical counterparts.

Why are conservative Protestants distinctive in their pro-life attitudes when compared to members of other faith traditions? As Hoffman and Johnson note (2005), abortion is the pivotal issue that brought conservative Protestants into the political arena in the 1970s, following Roe v. Wade and leading to the founding of the Moral Majority. As such, there has been a consistent message from church leadership that abortion is commensurate to murder, which has likely contributed to reduced heterogeneity on this topic among evangelicals. Given that conservative Protestantism is defined by its commitment to the authority of the Bible, which is viewed as the literal word of God, evangelical leadership often draws on Biblical texts to support their opposition to abortion. Predictably, scholars have consistently found an association between Biblical literalism and conservative outcomes on a range of social issues, including antiabortion orientations (Emerson 1996; Ogland and Bartkowski 2014; Ellison et al. 2005).

Although the Bible has little to say about abortion per se, conservative Protestants focus on passages that describe God as having intentionally “formed” human beings “in the womb” (e.g., Psalm 139:13–16; Isaiah 44:2, 24), which are interpreted as evidence that life begins at conception (Bartkowski et al. 2012). Such interpretations of Biblical texts are consistent with the pro-family worldview of conservative Protestantism, which centers on gender traditionalism, pro-natalism, and the sanctification of family life (Emerson 1996). Furthermore, some conservative Protestants believe that a woman’s increased control over her own fertility could undermine divinely ordained gender roles and increase the tendency of women to focus on careers to the detriment of family life (Ellison et al. 2005).

Like evangelical leadership, the Catholic Church has long opposed legalized abortion, often equating the practice to murder (Luker 1985). The official position of the Church on abortion is clearly articulated in the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception. From the first moment of existence, a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person—among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life (U.S. Catholic Conference 1994, p. 2273).

Despite clear statements from Church leadership condemning abortion, Catholics tend to hold more moderate views on this issue than their evangelical Protestant counterparts. Scholars have noted that American Catholics have long questioned papal authority and selectively appropriate Vatican doctrines on matters of sexuality (Greeley 1990; D’Antonio et al. 2007).

In addition to variations in abortion attitudes by religious affiliation , scholars have noted significant differences by religious practice. Individuals who attend church frequently, report high levels of religious salience, and pray often tend to hold more conservative abortion attitudes than those who attend church infrequently, report lower levels of religious salience, and pray less often (Emerson 1996; Bartkowski et al. 2012; Cook et al. 1992). These indicators of religious involvement may reflect strength of religious belief and commitment to religious principles. For example, attendance at religious services may increase familiarity with official church doctrines and offer a context for socialization on abortion and other social issues via sermons, classes, and informal social contacts with other church members. In their work on U.S. Hispanics, Ellison et al. (2005) show that it is important to consider the combination of religious affiliation and involvement. They find that Hispanic Protestants who attend church frequently are more strongly pro-life than any other segment of the Latino population. Committed Catholics also tend to hold pro-life views, but they are more likely to endorse an abortion ban that includes exceptions for rape, incest, and threats to the mother’s life. Finally, their work shows that Latino Protestants and Catholics who rarely attend religious services generally do not differ from religiously unaffiliated Hispanics in their abortion views.

4.2 Religion and Abortion Behaviors

While numerous studies have examined the relationship between religion and abortion attitudes, far fewer studies have focused on the effect of religion on abortion behavior. Early studies investigating the influence of religion on abortion behavior were largely based on comparisons between surveys of women at abortion clinics and surveys of the general population (Henshaw and Silverman 1987; Henshaw and Kost 1996). Employing a national survey of 9985 abortion patients, Henshaw and Kost (1996) revealed that while Catholic women were as likely as women in the general population to have an abortion, evangelical Protestant women were much less likely to do so. While informative, studies like these do not allow us to determine whether conservative Protestantism reduces the risk of abortion among pregnant women because evangelicals may be underrepresented at abortion clinics due to their lower likelihood of becoming pregnant out of wedlock. Studies of women at abortion clinics are also limited in their ability to assess causality given that information about personal religiosity is collected after the decision to abort has been made.

More recent scholarship by Amy Adamczyk on the connection between religion and abortion behaviors addresses many of the shortcomings of previous work in this area. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Adamczyk and Felson (2008) reveal that religiosity (i.e., frequency of prayer, service attendance, participation in youth group activities, and subjective religious importance) indirectly reduces the likelihood that a woman will have an abortion by reducing the probability that she will have an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Among those who become pregnant before marriage, religious women are more likely than secular women to marry the father of the child rather than get an abortion or carry the pregnancy to term outside of marriage. However, for those women who become pregnant and do not marry before the birth, religiosity is unrelated to the probability of having an abortion. Adamczyk and Felson (2008) also note several variations in the likelihood of having an abortion by religious affiliation . They find that women who identify as Catholic, mainline Protestant, and Jewish are more likely than conservative Protestant women to abort an out-of-wedlock pregnancy than carry it to term outside of marriage. Adamczyk and Felson (2008) suggest that conservative Protestants are less likely to have an abortion than mainline Protestants and Catholics due to cultural norms prioritizing motherhood and de-emphasizing educational achievement (Darnell and Sherkat 1997; Lehrer 1999). In follow-up work on the topic, Adamczyk highlights religious contextual variations in abortion behaviors. While living in a county with a higher proportion of conservative Protestants does not appear to influence abortion decisions (Adamczyk 2008), having attended a high school with a high proportion of conservative Protestants appears to discourage abortion (Adamczyk 2009b).

5 Religion and HIV/AIDS

Although previous sections of this chapter focus on research conducted on populations within the United States, much of the recent research on the connection between religion and HIV/AIDS has emphasized non-U.S. contexts, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). We begin this section by noting important research on the relationship between religion and HIV within the United States and then shift to research centered abroad.

5.1 Religion and HIV/AIDS in the United States

Scholarship on religious involvement and HIV/AIDS focusing on the U.S. context has concentrated on three themes: sexual risk taking, service provision by religious organizations (primarily churches), and religious coping among individuals living with HIV and their caregivers. Given that we have devoted the beginning of this chapter to examining the connection between religion and sexual behavior more generally, we only briefly discuss sexual risk-taking and focus primarily on the other two topics. A review of the literature on religion and sexual risk behaviors associated with HIV status (e.g., commercial sex and multiple partners) suggests that religiosity tends to reduce HIV risk (Shaw and El-Bassel 2014). The protective nature of religion appears to also extend to HIV positive individuals. Employing a nationally representative sample of 1421 people in care for HIV, Galvan et al. (2007) find that religiosity is associated with fewer sexual partners and a lower likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex.

Research examining care provided to individuals living with HIV by religious institutions suggests that churches play a limited, but potentially important, role in service provision for those who are HIV positive. Although faith-based organizations (FBOs) have provided a number of services- including organizing HIV testing (Whiters et al. 2010), prevention education (Agate et al. 2005; Lindley et al. 2010), and housing for HIV positive individuals (Derose et al. 2011)- involvement in HIV care and prevention is uncommon for religious congregations. Using data from a nationally representative sample of U.S. congregations, Frenk and Trinitapoli (2013) find that only 5.6 % provide programs or activities that serve people living with HIV/AIDS. Expectedly, congregational attitudes about HIV, homosexuality, and substance abuse are related to the type and intensity of events or programs focused on individuals with HIV (Bluthenthal et al. 2012). Other congregational characteristics appear to be associated with having programs directed at individuals living with HIV including: the presence of openly HIV positive people in the congregation, having a group within the church that assesses community needs, and religious tradition (Frenk and Trinitapoli 2013).

Finally, a number of U.S. studies have investigated the role of religion in coping with HIV. People living with HIV/AIDS often draw on religious resources to help reframe their lives, to overcome feelings of guilt and shame, and to bring a sense of meaning and purpose to their experience (Cotton et al. 2006; Siegel and Schrimshaw 2002; Pargament et al. 2004). Limited evidence suggests that greater engagement in spiritual activities is linked to positive mental health outcomes among HIV positive individuals, including lower levels of depression and distress and higher levels of optimism (Pargament et al. 2004; Simoni and Ortiz 2003; Biggar et al. 1999). Other research suggests that religion is protective against physical decline among individuals with HIV/AIDS. For example, Ironson et al. show that specific dimensions of spirituality (e.g., sense of peace, faith in God) are associated with better immune function (Ironson et al. 2002). More recent work by Ironson et al. (2011) finds that a positive view of God is associated with slower disease progression.

Although the tenor of research on religion and coping among individuals living with HIV is generally positive, a smaller body of research highlights the potentially negative effects of religion for this population. Drawing on a sample of 141 HIV positive African American women, Hickman et al. (2013) show that negative religious coping (e.g., viewing HIV as a punishment from God) is associated with poorer mental health and greater perceptions of stigma and discrimination. Other work shows that men with HIV who report more spiritual struggles (e.g., anger at God) display more depressive symptoms (Jenkins 1995). Finally, evidence suggests that holding a negative view of God (i.e., viewing God as harsh or punishing) is associated with faster disease progression among HIV positive individuals (Ironson et al. 2011).

5.2 Religion and HIV/AIDS in Africa

Recent research on the connection between religion and HIV/AIDs has focused on Africa, specifically Sub-Saharan Africa, for three key reasons. First, Africa is characterized by very high levels of religious involvement and a very diverse religious marketplace. In terms of religious make-up, Africa is roughly 50 % Christian and 42 % Muslim, with smaller numbers identifying with traditional African religions (Trinitapoli and Weinreb 2012). The area between the southern border of the Sahara and the tip of South Africa has been labeled “the most religious place on Earth” (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2010). Second, and perhaps most importantly, SSA is the center of the AIDS pandemic. In 2012, 70 % of all new cases of HIV were in the region, and AIDS accounted for 1.2 million deaths. It is important to note, however, that there is extremely high variation in HIV prevalence across the continent and within African countries (UNAIDS 2013). Finally, social scientists, particularly those in public health, have been interested in the connection between religion and HIV in Africa due to changes in the structure of international aid. Rather than working through governments, international assistance is primarily channeled through non-governmental agencies (NGOs), including faith-based organizations (FBOs). Public health officials have expressed concern that FBOs have increased the overtly religious tone of prevention messages and “moralized” the battle against AIDS. However, Trinitapoli and Weinreb (2012) argue that the incorporation of religion into the fight against AIDS, by loosening restrictions on funding, mirrors the trust of religious leaders in the region. Given that religious leaders are the most trusted authority figures in SSA (much more so than NGO officials or teachers), ignoring religious institutions as service providers potentially cuts off an important resource in the fight against HIV.

Much of the research on religion and HIV in Africa has examined religious variations in HIV risk and status. Evidence from Malawi (Trinitapoli and Regnerus 2006), South Africa (Garner 2000), Zimbabwe (Gregson et al. 1999), and Zambia (Agha et al. 2006) suggests that individuals who are members of more conservative religious denominations (i.e., Pentecostal and certain African Independent Churches) exhibit lower risk of HIV infection as compared to members of other religious faiths, perhaps due to their reduced likelihood of having extramarital partners. There is also limited evidence that Muslims in Africa display lower levels of HIV infection in comparison to other individuals (Gray 2004). Trinitapoli and Weinreb (2012) examine religious variations in HIV status, drawing on biomarker data from 3000 rural respondents in Malawi. Their results reveal few differences in HIV status across religious affiliations with the important exception that HIV is lower among New Mission Protestants (e.g., Church of Christ and Jehovah’s Witness) than among members of other religious affiliations . Evidence from their study suggests that individuals with higher levels of religious involvement are less likely to be HIV positive, leading Trinitapoli and Weinreb (2012) to conclude that religious affiliation or identity matters much less than being highly involved within one’s religious community.

In addition to studies examining religious variations in HIV risk and status, several studies have explored how religious congregations in Africa communicate information about HIV/AIDS to their congregants. A number of scholars have focused on religious opposition to condom use as a primary barrier to HIV prevention in SSA (Preston-Whyte 1999; Rankin et al. 2005; Epstein 2007). Yet evidence suggests that religious opposition to condom use varies considerably both across and within religious traditions. Similar to research conducted in the United States (Ellingson et al. 2001), findings from these studies suggest that many religious leaders understand the reality of nonmarital sex within their congregations; realizing that messages of sexual abstinence are not sufficient prevention efforts against HIV (Garner 2000; Trinitapoli and Weinreb 2012). Other evidence from a study of religious services in two districts of rural Malawi suggests that while condoms are often explicitly prohibited by church doctrine, some religious leaders encourage members who cannot abstain from sex to use a condom to avoid contracting HIV (Trinitapoli 2006).

6 Religion and the GLBT Community

The final substantive section of this chapter focuses on the connection between religion and the gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered (GLBT) community. Scholars interested in this connection have tended to pursue two distinct lines of research. The first line of inquiry centers on religious variations in attitudes toward GLBT individuals among the U.S. public, focusing on issues such as the morality of homosexual relationships , civil liberties, and gay marriage. The second line of scholarship focuses on how religion impacts the lives of members of the GLBT community. Scholarship in this area focuses on issues such as the level of involvement within religious organizations by gay individuals, the impact of religion on the identity of gay persons, and the connection between religion and mental health outcomes among GLBT individuals.

6.1 Attitudes Toward Gays and Lesbians

Several decades of scholarship have investigated the connection between religion and attitudes towards gays and lesbians. The liberalization of attitudes toward homosexuality in the United States over the past 30 years is well documented, with an accelerated rate of acceptance of GLBT rights in recent years. For example, between 2009 and 2014 the percent of U.S. adults who oppose gay marriage shifted from the majority (54 %) to a minority (39 %) (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2014).

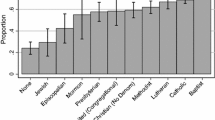

Oppositional attitudes towards gays and lesbians have long been associated with certain religious affiliations, beliefs and practices. Disapproval of same-sex marriage is increasingly concentrated among a few religious groups, namely evangelical Protestants, Black Protestants and other religious conservatives (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life 2014; Public Religion Research Institute 2014). Conservative Protestants typically hold the least accepting attitudes towards: homosexuality (Gay et al. 1996; Hill et al. 2004; Bean and Martinez forthcoming), extending basic civil liberties to gays and lesbians (Petersen and Donnenwerth 1998; Burdette et al. 2005), and gay marriage (Sherkat et al. 2011; Olson et al. 2006). Conversely, members of Jewish and mainline Protestant groups are typically the most liberal, followed by Catholics. Although there is limited research on Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists in the United States, evidence suggests that Muslims hold more disapproving views of homosexuality relative to those of other religious faiths (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009). Negative attitudes toward gays and lesbians among evangelical Protestants are explained in part by higher levels of church attendance , religious importance, beliefs in Biblical inerrancy (i.e., believing that the Bible is the literal word of God), and conservative political views, all of which are associated with oppositional attitudes towards gays and lesbians (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009; Whitehead 2010; Sherkat et al. 2011).

Beliefs in the doctrine of biblical literalism are directly connected to conservative Protestant opposition to homosexuality, as many conservative Protestants see the Bible as the ultimate source of authority, providing necessary and sufficient information about the conduct of human affairs and the answers to routine problems (Ellison et al. 1996). One of the most widely cited passages from the Old Testament is the account of Sodom in Genesis 19, involving the destruction of the city by God. This passage has been cited as evidence of the threat of sexual immorality, particularly homosexuality, although numerous biblical scholars have offered alternative interpretations (e.g., Boswell 1980; Helminiak 2000). Conservative Protestants more commonly cite New Testament passages as support of the harmful nature of homosexuality. Romans 1:26–27 is often quoted as evidence that homosexuality is both unnatural and perverse. In addition, 1st Corinthians 6:9–10 is often cited as supporting the idea that homosexuals will not be admitted to heaven unless they reform their behavior (Dobson 2000). Drawing on Biblical texts relating to appropriate relationships between husbands and wives (Ephesians 5:22–23, 1 Peter 3:1), or procreation (Genesis 1:27–28), evangelicals also advocate traditional views of marriage which stress sexual purity, gender complementarianism, and authoritative parenting (Regnerus 2007; Wilcox et al. 2004). As Bean and Martinez (forthcoming) note, same-sex unions violate the “biblical” family model because they do not draw on separate roles for men and women, namely the interdependence between male headship and female nurturance (Kenneavy 2012). Evangelicals are also more likely than members of other faiths to believe that gays and lesbians choose their orientation, rather than considering same-sex attraction an inborn trait (Whitehead 2010).

Despite long held opposition to same-sex relationships among evangelicals in the United Sates, there is some evidence of increasing tolerance toward the GLBT community among religious conservatives. Content analysis of popular evangelical literature (Thomas and Olson 2012), as well as public statements from powerful evangelical leaders like Pastor Rick Warren and Richard Cizik (former spokesperson for the National Association of Evangelicals), suggest that conservative Protestant leadership is liberalizing on GLBT rights. Bean and Martinez (forthcoming) argue that increasing ambivalence toward gays and lesbians extends to evangelical laity, as heterosexual evangelicals have become more aware of fellow Christians who “struggle” with same-sex attraction. Evangelicals draw on these personal experiences to form their attitudes towards the GLBT community. Yet competing scripts about homosexuality create practical dilemmas about how to “do” religion in particular social settings. Evidence suggests that younger evangelicals are more accepting of gay rights than previous cohorts, despite the increased attention to preserving “traditional” marriage among some religious conservatives (Farrell 2011; Putnam and Campbell 2012).

6.2 Religion in the Lives of Gays and Lesbians

Although there is a dearth of research focusing on levels of religious involvement among sexual minorities, evidence suggests that religion plays an important role in the lives many gays and lesbians in the United States (Cutts and Parks 2009; Sherkat, 2002; Rostosky et al. 2008). Drawing on nationally representative data, Sherkat (2002) finds that while sexual minorities are more likely to become apostates than female heterosexuals, they are no more likely to do so than heterosexual men. Additional findings from this study suggest that gay men are significantly more religiously active than male heterosexuals and other sexual minorities, displaying similar levels of religious activity to female heterosexuals. Other work confirms relatively high levels of religious involvement, particularly private religious behaviors, among gays and lesbians (Rostosky et al. 2008; Cutts and Parks 2009) .

A much larger body of research, almost exclusively qualitative in nature, has investigated the conflict between religious and queer identities. Given the level of diversely among religious faiths in attitudes towards the GBLT community, it is no surprise that the potential clash between sexual and religious identity varies greatly by religious tradition. Research suggests that identifying as gay or lesbian is most difficult for those raised in conservative religious environments, such as evangelical Protestant churches (Mahaffy 1996). The conflict between religious identity and GLBT identity also appears to be greater among those with high levels of religious salience (Kubicek et al. 2009). Direct experiences with homophobia found in conservative Protestant churches have been associated with a number of harmful outcomes, including fear of eternal damnation, depression, low self-esteem, and feelings of worthlessness (Barton 2010, 2012) .

Research focusing on the African American church paints a more nuanced picture of the relationship between religion and homosexual identity. Scholars note that homosexuality is generally rejected in Black churches, with most places of worship advocating a “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach to sexuality (Pitt 2010; Harris 2010). However, Fullilove and Fullilove (1999) note that gay men are given a special status within many churches because “they provide the creative energy necessary to the African American religious experience. Just as church women are responsible for nurturing and feeding the congregation, gays in the church are responsible for creating the music and other emotional moments that bring worshippers closer to God.” In his research focusing on religiously active gay Black men, Pitt (2010) shows that although most respondents have accepted both their gay and Christian identities, the majority vacillate on whether God approves of their sexual orientation, highlighting the underlying incompatibility between conservative religious doctrine and homosexuality .

Finally, several studies have focused on the experiences of gays and lesbians within gay-affirming churches, and the potential benefits of religious involvement for GLBT identity. Yip (2002) argues that religion provides a framework for practicing sexual inclusion, while scholars like Melissa Wilcox (2003) note that gays and lesbians are creating more inclusive Christian churches. In their research on the Metropolitan Community Church, Rodriguez and Ouellette (2000) find that higher levels of religious involvement correlate with successful integration of religious and sexual identities, arguing that the church plays a key role in identity integration. However, other work suggests that even gay-affirming churches may be limited in their inclusiveness. In her study of two gay affirming Protestant churches, McQueeney (2009) outlines a number of strategies that congregates use to accommodate-but not assimilate-to heteronormative conceptions of the “good Christian.” Strategies included minimizing one’s sexual identity and normalizing one’s sexuality by enacting Christian principles of monogamy, manhood, and motherhood. As a result, these churches create a space for gay and lesbian Christians to view their sexuality as natural, normal, and moral; yet these churches tend to be less welcoming to those individuals who do not conform to the notions of a “good Christian,” such as trangendered people and gender/sexual nonconformists .

7 Research Limitations and Future Directions

The research reviewed in this chapter is characterized by several limitations. In this section, we review these shortcomings. We also several highlight important directions for future research.

7.1 Measurement Issues

Although religion is a multidimensional phenomenon (Idler et al. 2003), most studies employ only one or two indicators of religious involvement (typically religious affiliation, church attendance, or religious salience) . Single items tend to have lower validity and reliability than multi-item indicators. Scholars have also questioned the usefulness of traditional measures of religious involvement, especially denominational affiliation (Alwin et al. 2006). Sociologists of religion have encouraged researchers to consider alternative forms of religious involvement, such as the use of online media and more individualized forms of religious expression, to adequately capture the current religious landscape (Roberts and Yamane 2011). Incorporating a broader array of measures of religion may deepen our understanding of the connections among religion, sexuality, and sexual health. Future research should also devote more attention to religious context (e.g., county-level religious climate and school-level religious context), rather than solely concentrating on individual-level religiosity.

7.2 Sexuality and Sexual Health Outcomes

Although previous research has examined a wide range of sexual health outcomes, this body of literature is heavily focused on adolescent sexual activity, especially the transition to first sex. Future research should consider a broader range of sexual health outcomes (e.g., contraceptive decision making, sexually transmitted infections, sexual satisfaction, and sexting) at different stages of the life course. With regard to sexuality, research should continue to consider how religious involvement impacts mental and physical health outcomes among GBLT individuals.

7.3 Indirect Effects

Previous research is also limited by theoretical models that overemphasize the direct effects of religion on sexuality and sexual health outcomes. While many studies speculate as to why religious involvement should impact sexuality and sexual health , few studies offer empirical support for these explanations. It is important for future research to examine understudied mechanisms linking religion and sexual health, including social networks, specific religious doctrines, psychological resources, and access to sexual health information and services. It is important to begin by establishing individual mechanisms. Then researchers should consider testing more elaborate theoretical models with complex casual chains.

7.4 Subgroup Variations

It is often unclear whether the association between religious involvement and sexual health varies according to theoretically relevant subgroups including gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexuality. Although some research has explored Black-White differences in the impact of religion on sexual health, there is a dearth of scholarship focused on how religion may impact sexuality or sexual health among Latinos and Asians. Research on how religion impacts the sexual activity of GLBT youths is also virtually non-existent. Furthermore, scholars should consider how the impact of religion on sexual health varies according to socioeconomic indicators like level of education. One question is whether education in some way counteracts the effects of religious involvement.

7.5 Alternative Explanations: Personality Traits and Social Desirability

Some scholars have suggested that the protective effects of religious involvement on sexual health outcomes may be explained by certain personality traits that select individuals into religious institutions. The most convincing arguments focus on traits like risk aversion, avoidance of thrill seeking, and self-control. Some evidence suggests that individuals with these characteristics are more likely to display both higher levels of religiosity and healthier lifestyles (Regnerus and Smith 2005). Because studies of religion and sexual health do not adjust for personality, there is little evidence for personality selection. However, it is reasonable to suggest that such personality traits could select certain individuals into risky sexual activities and out of religious institutions. Thus personality selection may account for at least some of the protective effects of religious involvement on certain sexual health outcomes.

Because the majority of research on religion , sexuality, and sexual health necessarily relies on self-reports of sexual behavior, there is some skepticism concerning the reliability of these data. To this point, however, there is little evidence to suggest any consistent association between religiosity and the tendency to give biased, socially desirable responses. At least one study of this issue among young adults argues strongly against such a view (Regnerus and Smith 2005). Nevertheless, it would be helpful for future studies to rule out obvious sources of response bias in work on religion and sexual health.

8 Conclusion

In this chapter, we provide an overview and critical examination of published research concerning the impact of religious involvement on the outcomes of sexuality and sexual health across the life course. We take a broad approach, focusing on a variety of important topics, including sexual behavior, sexual health education, abortion attitudes and behavior, HIV/AIDS, attitudes toward gays and lesbians, and the lived experiences of sexual minorities. In the future, researchers should (1) employ more comprehensive measures of religious involvement, (2) investigate understudied outcomes related to sexuality and sexual health, (3) explore mechanisms linking religion, sexuality, and sexual health, (4) establish subgroup variations in the impact of religious involvement, and (5) formally test alternative explanations like personality selection and social desirability. Research along these lines would certainly contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of religious variations in sexuality and sexual health across the life course.

References

Adamczyk, A. (2008). The effects of religious contextual norms, structural constraints, and personal religiosity on abortion decisions. Social Science Research, 37(2), 657–672.

Adamczyk, A. (2009a). Socialization and selection in the link between friends’ religiosity and the transition to sexual intercourse. Sociology of Religion, 70(1), 5–27.

Adamczyk, A. (2009b). Understanding the effects of personal and school religiosity on the decision to abort a premarital pregnancy. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 50(2), 180–195.

Adamczyk, A., & Felson, J. (2006). Friends’ religiosity and first sex. Social Science Research, 35(4), 924–947.

Adamczyk, A., & Felson, J. (2008). Fetal positions: Unraveling the influence of religion on premarital pregnancy resolution. Social Science Quarterly, 89(1), 17–38.

Adamczyk, A., & Hayes, B. E. (2012). Religion and sexual behaviors: Understanding the influence of Islamic cultures and religious affiliation for explaining sex outside of marriage. American Sociological Review, 77(5), 723–746.

Adamczyk, A., & Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: The role of religion and cultural context. Social Science Research, 38(2), 338–351.

Addai, I. (2000). Religious affiliation and sexual initiation among Ghanaian women. Review of Religious Research, 41, 328–343.

Agate, L. L., Cato-Watson, D., Mullins, J. M., Scott, G. S., Rolle, V., Markland, M., & Roach, D. L. (2005). Churches United to Stop HIV (CUSH): a faith-based HIV prevention initiative. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(Suppl. 7), 60.

Agha, S. (2009). Changes in the timing of sexual initiation among young Muslim and Christian women in Nigeria. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(6), 899–908.

Agha, S., Hutchinson, P., & Kusanthan, T. (2006). The effects of religious affiliation on sexual initiation and condom use in Zambia. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(5), 550–555.

Alwin, D. F., Felson, J. L., Walker, E. T., & Tufiş, P. A. (2006). Measuring religious identities in surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70(4), 530–564.

Arsneault, S. (2001). Values and virtue: The politics of abstinence-only sex education. The American Review of Public Administration, 31(4), 436–454.

Atkins, D. C., & Kessel, D. E. (2008). Religiousness and infidelity: Attendance, but not faith and prayer, predict marital fidelity. Journal of Marriage & Family, 70(2), 407–418.

Barkan, S. E. (2006). Religiosity and premarital sex in adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 407–417.

Barrick, A. (2010). Most Evangelical leaders OK with birth control. http://www.christianpost.com/news/most-evangelical-leaders-okwith-birth-control-45493/. Accessed 3 June 2014.

Bartkowski, J. P., Ramos-Wada, A. I., Ellison, C. G., & Acevedo, G. A. (2012). Faith, race-ethnicity, and public policy preferences: Religious schemas and abortion attitudes among U.S. Latinos. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(2), 343–358.

Barton, B. (2010). “Abomination”—life as a bible belt gay. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(4), 465–484.

Barton, B. (2012). Pray the gay away: The extraordinary lives of Bible Belt Gays. New York: New York University Press.

Bean, L., & Martinez, B. C. (forthcoming). Evangelical ambivalence toward gays and lesbians. Sociology of Religion.

Bearman, P. S., & Brückner, H. (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology, 106(4), 859–912.

Beck, S. H., Cole, B. S., & Hammond, J. A. (1991). Religious heritage and premarital sex: Evidence from a national sample of young adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30(2), 173–180.

Biggar, H., Forehand, R., Devine, D., Brody, G., Armistead, L., Morse, E., & Simon, P. (1999). Women who are HIV infected: The role of religious activity in psychosocial adjustment. Aids Care, 11(2), 195–199.

Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., & Fishbein, M. (2006). Public opinion on sex education in US schools. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(11), 1151–1156.

Bluthenthal, R. N., Palar, K., Mendel, P., Kanouse, D. E., Corbin, D. E., & Pitkin Derose, P. (2012). Attitudes and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS in urban religious congregations: Barriers and opportunities for HIV-related interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 74(10), 1520–1527.

Boonstra, H. (2010). Sex education: another big step forward—and a step back. The Guttmacher Policy Review, 13, 27–28.

Boswell, J. (1980). Christianity, social tolerance, and homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brewster, K. L., Cooksey, E. C., Gulkey, D. K., & Rindfuss, R. R. (1998). The changing impact of religion on the sexual and contraceptive behavior of adolescent women in the United States. Journal of Marriage & Family, 60(2), 493–504.

Brimeyer, T. M., & Smith, W. L. (2012). Religion, race, social class, and gender Differences in dating and hooking up among college students. Sociological Spectrum, 32(5), 462–473.

Brückner, H., & Bearman, P. (2005). After the promise: The STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(4), 271–278.

Burdette, A. M., & Hill, T. D. (2009). Religious involvement and transitions into adolescent sexual activities. Sociology of Religion, 70(1), 28–48.

Burdette, A. M., Ellison, C. G., & Hill, T. D. (2005). Conservative Protestantism and tolerance toward homosexuals: An examination of potential mechanisms. Sociological Inquiry, 75, 177–196.

Burdette, A. M., Ellison, C. G., Sherkat, D. E., & Gore, K. A. (2007). Are there religious variations in marital infidelity? Journal of Family Issues, 28, 1553–1581.

Burdette, A. M., Ellison, C. G., Hill, T. D., & Glenn, N. D. (2009). “Hooking up” at college: Does religion make a difference? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(3), 535–551.

Burdette, A. M., Haynes, S. H., Hill, T. D., & Bartkowski, J. P. (2014.) Religious variations in perceived infertility and inconsistent contraceptive use among unmarried young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 704–709.

Carpenter, L. M. (2011). Like a virgin…again?: Secondary virginity as an ongoing gendered social construction. Sexuality & Culture, 15(2), 115–140.

Cochran, J. K., & Beeghley, L. (1991). The influence of religion on attitudes toward nonmarital sexuality: A preliminary assessment of reference group theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30(1), 45–62.

Cook, E. A., Jelen, T. G., & Wilcox, C. (1992). Between two absolutes: Public opinion and the politics of abortion. Boulder: Westview.

Cooksey, E. C., Rindfuss, R. R., & Guilkey, D. K. (1996). The initiation of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior during changing times. Journal of Health & Social Behavior, 37(1), 59–74.

Cotton, S., Puchalski, C. M., Sherman, S. N., Mrus, J. M., Peterman, A. H., Feinberg, J., Pargament, K. I., Justice, A. C., Leonard, A. C., & Tsevat, J. (2006). Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal Of General Internal Medicine, 21(S5), S5–S13.

Cutts, R. N., & Parks, C. W. (2009). Religious involvement among black men self-labeling as gay. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(2–3), 232–246.

D’Antonio, W. V., Davidson, J. D., Hoge, D. R., & Gautier, M. L. (2007). American Catholics today: New realities of their faith and their church. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Darnell, A., & Sherkat, D. E. (1997). The impact of Protestant fundamentalism on educational attainment. American Sociological Review, 62, 306–315.

Davidson, J. L., Moore, N. B., & Ullstrup, K. M. (2004). Religiosity and sexual responsibility: Relationships of choice. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28(4), 335–346.

Davidson, L. A., Pettis, C. T., Joiner, A. J., Cook, D. M., & Klugman, C. M. (2010). Religion and conscientious objection: A survey of pharmacists’ willingness to medications. Social Science & Medicine, 71(1),161–165.

Derose, K. P., Mendel, P. J., Palar, K., Kanouse, D. E., Bluthenthal, R. N., Castaneda, L. W., Corbin, D. E., Domínguez, B. X., Hawes-Dawson, J., & Mata, M. A. (2011). Religious congregations’ involvement in HIV: A case study approach. AIDS and Behavior, 15(6),1220–1232.

De Visser, R. O., Smith, A. M. A., Richters, J., & Rissel, C. E. (2007). Associations between religiosity and sexuality in a representative sample of Australian adults. Archives of sexual behavior, 36(1), 33–46.

Doan, A. E., & McFarlane, D. R. (2012). Saying no to abstinence-only education: An analysis of state decision-making. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 42(4),613–635.

Dobson, J. (2000). Complete marriage and family home reference guide. Wheaton: Tyndale House Publishers.

Edwards, L. M., Haglund, K., Fehring, R. J., & Pruszynski, J. (2011). Religiosity and sexual risk behaviors among Latina adolescents: Trends from 1995 to 2008. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(6), 871–877.

Ellingson, S., Tebbe, N., Van Haitsma, M., & Laumann, E. O. (2001). Religion and the politics of sexuality. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 30, 3–55.

Ellison, C. G., Bartkowski, J. P., & Segal, M. L. (1996). Conservative Protestantism and the parental use of corporal punishment. Social Forces, 74, 1003–1028.

Ellison, C. G., Echevarría, S., & Smith, B. (2005). Religion and abortion attitudes among U.S. Hispanics: Findings from the 1990 Latino National Political Survey. Social Science Quarterly (Wiley-Blackwell), 86(1), 192–208.

Ellison, C. G., Wolfinger, N. H., & Ramos-Wada, A. I. (2013). Attitudes toward marriage, divorce, cohabitation, and casual sex among working-age Latinos does religion matter? Journal of Family Issues, 34(3), 295–322.

Emerson, M. O. (1996). Through tinted glasses: Religion, worldviews, and abortion attitudes. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 35(1), 41.

England, P., Fitzgibbons Shafer, E., & Fogarty, A. C. K. (2007). Hooking up and forming romantic relationships on today’s college campuses. In M. S. Kimmel & A. Aronson (Eds.), The gendered society reader. New York: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, H. (2007). The invisible cure: Africa, the West, and the fight against AIDS. New York: Macmillan.

Farrell, J. (2011). The young and the restless? The liberalization of young evangelicals. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(3), 517–532.

Finer, L. B., & Henshaw, S. K. (2006). Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(2), 90–96.

Finer, L. B., & Philbin, J. M. (forthcoming). Trends in ages at key reproductive transitions in the United States, 1951–2010. Women’s Health Issues.

Finke, R., & Adamczyk, A. (2008). Explaining morality: Using international data to reestablish the macro/micro link. Sociological Quarterly, 49(4), 617–652.