Abstract

Although the economic importance of entrepreneurship has been formally recognized at least since the times of Schumpeter over 100 years ago, purposeful policy efforts to harness this driver of economic growth originated substantially later. It is really during the past 30 years or so that policymakers have started to target small- and medium-sized firms and new entrepreneurs.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Total Factor Productivity

- National System

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

- Output Indicator

- Entrepreneurship Literature

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

2.1 Introduction

Although the economic importance of entrepreneurship has been formally recognized at least since the times of Schumpeter over 100 years ago, purposeful policy efforts to harness this driver of economic growth originated substantially later. It is really during the past 30 years or so that policymakers have started to target small- and medium-sized firms and new entrepreneurs. Policy initiatives have gradually grown more refined over time, and today many talk about “entrepreneurship ecosystems,” a term used to refer to a palette of policy measures that address the broad range of needs new ventures have during their early life cycle. However, such policies often are based on a relatively narrow conception of how entrepreneurship actually contributes to economic growth. While a broad range of benefits has been associated with entrepreneurship, ranging from innovation (Acs and Audretsch 1988) to job creation (Blanchflower 2000; Parker 2009) to productivity (e.g., van Praag 2007), a coherent framework articulating such benefits has been lacking. To address this gap and to provide a coherent theoretical grounding for the GEDI approach, we have advanced the theory of National Systems of Entrepreneurship (Acs et al. 2013).

In this chapter, we lay out the main features of this theory and illustrate how the GEDI methodology captures its core features. We propose that a major shortcoming in policy thinking is the failure to recognize that entrepreneurship is a systemic phenomenon and should be approached as such. The concept of National Systems of Entrepreneurship addresses that gap by recognizing the systemic character of country-level entrepreneurship, and the fact that entrepreneurial processes are fundamentally driven by individuals, despite being embedded in a country-level context. Finally, we illustrate how the GEDI method can be harnessed for entrepreneurship policy analysis, design, and implementation.

2.2 The National Systems of Innovation

From the times of Adam Smith (1723–1790) and David Ricardo (1772–1823), many theories have been advanced to explain economic development. With the exception of Schumpeter, however, these theories have tended to overlook entrepreneurship as a potentially useful economic function that drives growth. Schumpeter famously identified entrepreneurs as “agents of creative destruction” who challenge industry incumbents by introducing new products, services, innovative processes, and organizational innovations that offer greater value than what the incumbents are able to offer. Industry incumbents, Schumpeter argued, are by nature monopolistic and prefer to establish and exploit a status quo, and without the challenges presented by entrepreneurs, they would stop innovating and be content just to exploit their market leadership. By innovating, entrepreneurs force incumbents to upgrade their game or to exit the market if they cannot. To Schumpeter, this creative destruction was the ultimate source of economic development.

Schumpeter preferred this entrepreneur-centric model early on, but he later changed his mind, prompted by the emergence of large corporations with dedicated R&D laboratories. Schumpeter came to believe that this change enabled large corporations to internalize technological development, and the economies of scale in R&D meant that new entrepreneurs could no longer effectively challenge incumbents for market leadership. Schumpeter’s “Mark II” model was later to dominate the Schumpeterian approach to explaining economic development, while the entrepreneur-centric “Mark I” model was largely ignored.

Modern theorizing about economic growth begun with the work of Solow (1957), who explored the relationships among labor, capital investment, and economic output. They theorized that increasing capital investment leads to greater economic growth, since capital investment enables a more effective use of labor. However, diminishing returns to this investment mean that, beyond a certain point, additional capital investment will stop producing additional economic growth. The only way to move beyond this steady state is through technological advances. This was the infamous Solow residual, which treated technological development as exogenous to the economic system.

Another pair of economists, Paul Romer and Robert Lucas Jr., were not satisfied with the Solow theory and sought to make technological development part and parcel of economic dynamism. Human capital and technological innovation were central notions in their theory, which posited that human capital exhibits increasing returns and that well-educated individuals tend to invent new things. Attempts to take advantage of those new things (i.e., technological advances) are what drive economic growth. Interestingly, they also used the term “entrepreneur,” although not to refer to individuals who start new firms but to inventors who create and exploit technological advances.

Romer (1990) and Lucas (1988) were influential in using technological innovation as a central, endogenous variable in explaining economic development. However, they did not elaborate much on how these advances were produced. To address this gap, economic historians and innovation sociologists started to explore in greater detail the determinants of countries’ innovative performance. This effort gave rise in the early 1990s to the concept and theory of National Systems of Innovation (NSI) (Edquist 1997; Lundvall 1992; Nelson 1993). This new literature maintained that innovation and the accumulation of knowledge are the fundamental drivers of economic growth. In economic systems, knowledge is produced in a cumulative and iterative fashion, and the process itself is regulated by a country’s institutions (Lundvall 1999). Because the process of creating knowledge is embedded in a country’s institutional context, it cannot be properly understood without considering the context within which the process is embedded. This also means that the “linear model of innovation,” in which knowledge outputs are gradually refined and moved from basic research to applied R&D and eventually to the market, was oversimplifying because it did not consider context and assumed that individual firms were mainly responsible for a country’s innovation performance. The NSI literature instead maintained that a country’s innovation performance is determined by the structure of its National System of Innovation. It is this structure, and interactions between the institutional operators within it, that determines a country’s innovation outcomes. Consequently, substantial time and effort were dedicated to describing different national (and, subsequently, sectoral) systems of innovation: how they functioned, their structure, interactions between different organizations, and so on.

Although the concept of NSI inspired a significant literature that explored determinants of country-level innovation, this literature also had a number of shortcomings. Ironically, although it drew significant inspiration from Schumpeter, the NSI literature failed to consider the actions of entrepreneurs to any extent. Instead of Schumpeter’s entrepreneur-centric Mark I model of innovation, this literature was mainly influenced by Schumpeter’s later Mark II model, which emphasized the role of large firms in innovation. Consequently, the NSI literature became preoccupied with static structure while ignoring entrepreneurial agency. In this structural tradition, “institutions engender, homogenize, and reinforce individual action: It is a country’s institutions that create and disseminate new knowledge and channel it to efficient uses” (Acs et al. 2013). Institutions and structures somehow produce and disseminate new knowledge, and the motivations, aspirations, and activities of individuals do not really matter. The key is to get structures right, and action will follow. Because of this emphasis, the NSI literature acquired quite a static flavor and was seen by many as unable to really predict innovation performance, rather than simply explaining it.

The NSI literature has consistently had a strong descriptive emphasis, yet it has never had a single, coherent theoretical grounding. Because of this, NSI research has primarily explored description rather than prescription, not to mention prediction. Therefore, while the NSI literature has been influential and informative, its popularity has also waned somewhat in recent years.

One may speculate why the NSI literature has so consistently failed to incorporate entrepreneurship as a central element of innovation production. Perhaps one important reason is that its routine-reinforcing and structural emphasis is difficult to reconcile with the entrepreneurship literature, which breaks routines and is individual centric. Nevertheless, entrepreneurs still are largely ignored by theories of economic development and growth, and calls for policies that harness entrepreneurship for economic growth therefore remain, strictly speaking, without a strong theoretical foundation.

This problem is due in part to the corresponding failure of entrepreneurship research to systematically address the broader macroeconomic implications of entrepreneurial action, as well as the regulating influence that an entrepreneur’s context exercises on that action. Simplistically put, whereas the NSI literature has been all about context at the expense of the individual, the entrepreneurship literature has been all about the individual at the expense of context. The heterogeneous literature on entrepreneurship has, for the most part, focused on the individual—that is, the entrepreneur—and on the new venture. Although the research questions addressed by the entrepreneurship literature are varied, it is fair to say that this literature has been preoccupied by two major questions: What factors propel some individuals to start new firms, and what factors explain the growth of new ventures? We know a good deal about who starts new firms and why, and about what makes new firms successful, but we still know relatively little about when and how entrepreneurship contributes to economic development.

2.2.1 National Systems of Entrepreneurship

We propose that a way out of this “institutions versus the individual” dilemma is to think about the role the entrepreneur’s context plays, not only in regulating opportunities and considering personal feasibility and the desirability of entrepreneurial action, but also in regulating the outcomes of that action (Acs et al. 2013). To start understanding how entrepreneurs might contribute to economic development, it is important to note several salient characteristics of entrepreneurial action:

-

1.

Entrepreneurial action takes place within uncertainty; entrepreneurs take risks when creating new firms to pursue perceived opportunities.

-

2.

Entrepreneurial action involves mobilizing resources; entrepreneurs need to access and mobilize their own resources and those controlled by others in order to pursue opportunities.

-

3.

The great majority of entrepreneurial actions are initiated by individuals or teams of individuals.

-

4.

Entrepreneurs’ actions in pursuing opportunities are regulated not only by the entrepreneurs’ perception of the opportunity but by their perception of the desirability and feasibility of the pursuit.

-

5.

The consequences of entrepreneurial action are regulated not only by the entrepreneurs’ own competencies but also by a number of contextual factors, such as the availability of external resources and access to markets.

To understand entrepreneurship as a systemic process, it is important to emphasize the resource mobilization aspect of entrepreneurial action. As entrepreneurs mobilize resources to pursue opportunities, it creates “entrepreneurial churn” (Reynolds et al. 2005), which should put resources to productive use. Because of uncertainty, entrepreneurs mobilize resources on a hunch. If this hunch proves correct, there is an opportunity to mobilize resources for value-adding uses. If the entrepreneur guesses wrong, however, she or he will stop pursuing the opportunity and the mobilized resources will be put to alternative uses. The net total of this activity, therefore, should be the allocation of human capital and resources to value-adding uses, which should drive total factor productivity.

At the macro level, therefore, entrepreneurship operates as a trial-and-error resource allocation process, which itself is driven by a multitude of entrepreneurial decisions made by individuals. Importantly, this process is regulated by contextual factors. For example, to act on perceived opportunity, the prospective entrepreneur must see the opportunity as feasible and desirable. Perceptions of feasibility will be regulated by factors such as resource availability, market openness, property protection, and so on. Perceptions of desirability will be regulated by factors such as perceived social norms, general attitudes toward entrepreneurship, and culture, to name a few. Furthermore, once the entrepreneur has decided to act, the context will regulate the likely outcomes of this action, for example, through resource availability, market openness, and other such factors.

The two key issues to understand in the above are (1) that without individual-level decisions to act, there will be no action; and (2) that the context will regulate who decides to act. The most important shortcoming of the NSI literature was that it ignored individuals and assumed that structure is sufficient to generate knowledge flows. The big omission of the entrepreneurship literature has been its failure to treat entrepreneurship as contextually embedded action. As we have highlighted above, both aspects are important, and we maintain that economic development cannot be fully understood without giving attention to both the individual and the context within which this individual is embedded. Consistent with the reasoning above, we propose the following definition of National Systems of Entrepreneurship:

A National System of Entrepreneurship is the dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction by individuals between entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations, which drives the allocation of resources through the creation and operation of new ventures.

Our definition adds important insight to the conception in Austrian economics of entrepreneurship as a market discovery process (Kirzner 1997). In the Austrian theory, entrepreneurs are ascribed the role of driving market learning; they help markets move toward a state of equilibrium by initiating competitive actions and reacting to such actions that are initiated by others. Our definition adds to this conception the important notion of resource mobilization, which helps connect micro-level entrepreneurial action with growth in total factor productivity. The Austrian school also treats entrepreneurship as a market function rather than an individual-level action; thus, it is assumed that any individual will act as soon as they stumble upon a market inefficiency. We instead emphasize the psychology and cognition of the entrepreneur, who will not necessarily act unless they perceive the pursuit of opportunity to be feasible and desirable. Because these judgments are regulated by perceived social norms, for example, it follows that a given individual may or may not choose to act, depending on the context they are in. Instead of acting automatically, as the Austrian school assumes, our theory emphasizes the conditioning effect context has on an individual’s behavior.

The core assumptions of the National Systems of Entrepreneurship theory are as follows:

-

1.

Economic growth is ultimately driven by a trial-and-error resource allocation process, under which entrepreneurs allocate resources toward productive uses;

-

2.

This process is driven by individual-level decisions, but those decisions are conditioned by contextual factors;

-

3.

The outcomes of individual-level entrepreneurial decisions are also conditioned by contextual factors; and

-

4.

Because of the multitude of interactions, country-level entrepreneurship is best thought of as a system, the components of which coproduce system performance.

All these notions are captured by the GEDI methodology, which represents operationalization of the National Systems of Entrepreneurship theory. To illustrate how the GEDI differs from other national-level conceptions of entrepreneurship, we next review country-level indicators of entrepreneurship.

2.3 Measuring Entrepreneurship at the Country Level

Although there is no formal country-level theory of entrepreneurship, attempts to measure the “entrepreneurial character” of countries have been quite numerous. Broadly speaking, measures of country-level entrepreneurship fall into three categories: output, attitude, and framework indicators.

Output indicators track new firms, new incorporations, and the prevalence of self-employment within a given population. These measures are obtained from business registries, employment registries, or survey data. One survey-based output indicator is the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), which surveys individuals’ attempts to create new ventures by drawing on survey samples of at least 2,000 adult individuals per country to obtain a country’s total early-stage entrepreneurial activity rate, which represents the rate of “nascent” and “new” entrepreneurs in the adult population (Reynolds et al. 2005). Registry-based output measures include OECD-Eurostat’s Entrepreneurship Indicators Program (Lunati et al. 2010; OECD-Eurostat 2007) and the World Bank’s Entrepreneurship Survey (World Bank 2011). The OECD high-growth firm indicator uses business registries to create an index of the prevalence of high-growth firms, relative to the overall population of registered companies. A high-growth firm is a registered firm (trade registry, employment registry, etc.) that has achieved at least 60 % employment growth during a period of 2 years, with at least 20 % annual growth each year, and which employed at least 10 people at the beginning of the period (OECD-Eurostat 2007). The World Bank Entrepreneurship Survey relies on business registry data to monitor new business incorporations.

Thus, output indicators consider a country to be entrepreneurial if it has a high number of individuals trying to start new ventures or if its business registries report a high number of new incorporations. The strength of such measures is that they register “real” activity, (although many incorporations may not become active operating units). A weakness of such measures, however, is that they tend to focus on aggregates of micro-level activity while ignoring the context in which this activity is embedded. This means that any systemic aspects of the entrepreneurial process are essentially ignored by output indicators.

Attitude measures monitor a country’s opinion and behavior toward entrepreneurship. Examples include the Eurobarometer survey (Gallup 2009), the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP 1997), and the GEM survey. Such surveys typically monitor a range of attitudes toward entrepreneurship, such as the preference for being self-employed, reasons for preferring self-employment (or not), and attitudes toward entrepreneurs (including their success and failure). Thus, entrepreneurial countries are those where the population exhibits a positive attitude toward entrepreneurship or a strong preference for self-employment as a career choice. While such surveys provide interesting insight into a country’s opinion climate or perhaps its entrepreneurial culture, they tell us little about actual entrepreneurial activity. Attitudes do not always translate into action, and we also do not know whether attitudes drive or are driven by entrepreneurial action.

The third category of entrepreneurship indicators attempts to measure the framework conditions for entrepreneurship. One example is the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Survey, which monitors national regulations for business entry and operation (Djankov et al. 2002). Another is the OECD Entrepreneurship Indicators Program, which has developed a more comprehensive framework measure that distinguishes between framework conditions, entrepreneurship performance, and economic impact (Ahmad and Hoffmann 2008). While useful for tracking the regulatory context for entrepreneurship, including entrepreneurship policy, such measures lack connectivity with entrepreneurial activity. For these measures, an “entrepreneurial country” is one where business regulations favor new business entry and operation. However, it is not certain that a favorable regulatory framework is all that is needed to promote an entrepreneurial economy. If, for example, attitudes toward entrepreneurship are negative, light-touch regulations may not be sufficient to attract the high-quality, ambitious entrepreneurial businesses that are most likely to drive economic growth.

In sum, approaches to measuring entrepreneurship in various countries reflect different conceptions of what it means to be an entrepreneurial country. However, none of the measures fully captures the systemic character of country-level entrepreneurial processes, as emphasized in the theory of National Systems of Entrepreneurship:

-

Output indicators are aggregates of micro-level activity that tend to ignore context.

-

Attitude indicators reflect attitudes toward entrepreneurship but do not link them to activities or policy frameworks.

-

Framework indicators only measure the regulatory and policy context while ignoring individual-level activity.

Each of these approaches is deficient from a systemic perspective. New firm counts tell us little about the processes that drive those outputs. Neither attitude measures nor framework measures tells us much about activity. To consider the system as a whole, a measurement approach is required that recognizes that

-

Country-level entrepreneurship is a systemic phenomenon where many components interact to produce system performance;

-

Both individuals and contexts matter in this process, and they influence one another; and

-

The process itself is complex and comprises many facets.

The GEDI methodology has been designed to capture these core features of the National Systems of Entrepreneurship theory. It approaches country-level entrepreneurship as a systemic phenomenon, which is driven by the interaction between individual-level actions and country-level framework conditions. The systemic features of the theory are captured by the GEDI’s:

-

1.

Contextualization of individual-level data by weighting it with data describing a country’s framework conditions. This approach captures the notion that individual-level activities are regulated by context.

-

2.

Use of 15 context-weighted measures of entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations, which are further organized into three subindices. This approach captures the notion that country-level entrepreneurial processes are complex and multifaceted.

-

3.

Application of the Penalty for Bottleneck algorithm, which captures the notion that system components coproduce system output.

-

4.

Consequent recognition that national entrepreneurial performance may be held back by bottleneck factors; for example, poorly performing pillars that may constrain system performance.Footnote 1

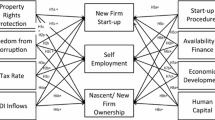

As a multifaceted index, the GEDI recognizes that country-level entrepreneurship is a complex phenomenon that cannot be satisfactorily captured by single-item aggregates or by focusing exclusively on attitudes, abilities, or aspirations. Nor can it be captured by considering the framework conditions alone. What is needed, therefore, is an approach that combines all of the above. The GEDI does this by using 15 measures of entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations and by weighting them with descriptors of country-level framework conditions (Fig. 2.1).

The GEDI also captures system dynamics, going beyond traditional, linear additive index approaches. Traditional indices are summative—or, as we like to call them, “cake” indices—simply adding together different component values. As long as the sum of components is greater than some threshold value, all is considered well. This is similar to being advised to compensate for missing sugar when baking a cake by adding more flour. Although the total weight of ingredients is the same, everyone recognizes that it is difficult to bake a good cake without sugar.

By applying the Penalty for Bottleneck approach, the GEDI methodology captures the notion that systems, by definition, comprise multiple components, and that these components coproduce system performance. These are defining characteristics of any system, which simple summative indices fail to capture. In a simple summative index, each system component contributes directly and independently to system performance. In the context of entrepreneurship, this would mean, for example, that a national measure of education would, directly and independent of other system components, contribute to “national entrepreneurship,” while in reality, we know that education cannot contribute much to a country’s entrepreneurial performance if individuals fail to act. On the other hand, if education was absent, the economic potential of entrepreneurial entries would be severely constrained. Moreover, even if both education and agency were present, country-level entrepreneurial performance would be constrained if, for example, growth aspirations were missing or if there were no financial resources available to feed the growth of new ventures. A simple summative index would fail to recognize such interactions, thereby ignoring crucial aspects of system-level performance.

As an important methodological innovation, the GEDI captures such system dynamics with the Penalty for Bottleneck method. As explained in more detail in Chap. 5, the GEDI is optimized to produce the highest index value when all individual component (or pillar) values (after normalization) are more or less even—in other words, when there are no major gaps between the pillars. A higher index value reflects the notion that a system’s performance is optimized when its individual components are in balance. If there are major performance differences between individual pillars—that is, bottleneck factors exist within the system—the values of well-performing pillars are “penalized” by adjusting them downward. This reflects a situation where some system components constrain system-level performance, much like a chef who cannot make full use of the ingredients of a particular dish if important ingredients are in short supply.

These methodological characteristics can provide important insights into the workings of National Systems of Entrepreneurship. Essential to the notion of bottlenecks is that some factors may unduly constrain system performance beyond their “objective” or stand-alone importance. Returning to the baking analogy, although only a little yeast is required to bake bread, without it the bread will not be good, no matter how much flour is on hand. With the Penalty for Bottleneck methodology, it is possible to identify both where bottleneck factors might lurk in any given system and how much system performance suffers as a result. A corollary would be that by mixing relatively little yeast in with the other ingredients, it is possible to improvement the bread significantly at relatively little cost. These features greatly enhance the utility of the GEDI methodology for entrepreneurship policy analysis and design, as the notion of bottlenecks allows policymakers to hone in quickly on possible constraints that might hold back system performance. We now will illustrate how the GEDI can be used to build a coherent national entrepreneurship policy program with the engagement of all stakeholders.

2.4 Using the GEDI to Analyze National Systems of Entrepreneurship

The Scottish example highlights the usefulness of the GEDI method as a policy analysis, planning, and implementation platform. In 2012, Scotland was participating in a joint effort with other countries to review their entrepreneurship ecosystems. However, while Scotland had access to multiple sources of data, none of them provided the kind of comprehensive systems perspective required for this exercise. It struck the Scottish team that a regionalized GEDI approach could provide just the kind of comprehensive perspective and a rigorous approach to assessing the entrepreneurial capacity in a region, as their purposes required. However, they also recognized first, that the GEDI analysis was only as good as the quality and choice of data, and second, that it could stimulate wider debate on the health of an innovative entrepreneurial ecosystem without acting like some computerized “policy-creating machine.”

Policymakers think increasingly about entrepreneurship support in ecosystem terms. Therefore, they want to know how they can achieve the most leverage in facilitating an entrepreneurial ecosystem. To achieve this, policymakers need comprehensive data on all aspects of the system—that is, on all ecosystem pillars. Importantly, insight is needed not only into how different pillars perform but also on how they are related to one another. Unfortunately, although the GEDI methodology allows system pillars to interact, it does so under the simplifying assumption that all of them interact equally with one another. While this simplifying assumption is necessary and sufficient for generic comparisons between countries, more detail is needed for purposeful policy analysis and design. Therefore, for policy design purposes, the boilerplate GEDI analysis has to be supplemented by expert judgments made by people who know at least some aspects of the system intimately. In Scotland, a series of policy stakeholder workshops was organized to extract this insight from stakeholders within the system.

The Scottish policy stakeholder engagement process was initiated and coordinated by Scottish Enterprise, an economic development agency. The first step was to commission a boilerplate GEDI analysis from the GEDI team, which also involved adjusting the global index pillars to include Scotland-specific pillar measures. For the boilerplate analysis, Scottish Enterprise requested that the GEDI team rank Scotland’s pillars in two ways: first, against all countries in the GEDI database; and second, against a subset of high-income economies. It also requested direct benchmarking comparisons against two groups of nations: first, the UK Home Nations (i.e., England, Wales, and Northern Ireland); and second, against the “Arc of Prosperity” countries (i.e., Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Republic of Ireland). The first benchmark compared Scotland’s performance against peers that were as similar as possible. The second benchmark compared Scotland against small, prosperous, open economies, which were able to offer Scotland aspirational benchmarks in selected domains.

The boilerplate GEDI report contained three analyses:

-

GEDI pillar numbers for Scotland: individual-level data, institutional data, and pillar values

-

Scotland rankings relative to the world and to high-income countries, respectively, for all pillars (including individual-level and institutional data rankings)

-

Benchmarking comparisons in the form of spider-web graphs

-

A “policy portfolio optimization” analysis, which identified priority pillars to improve with a view to enhancing the performance of the Scottish National System of Entrepreneurship.

A series of three policy stakeholder engagement workshops was then organized to debate the GEDI analysis. Approximately, a dozen policy stakeholders were invited to each workshop, each representing a different part of the Scottish entrepreneurship ecosystem, including banks, policy agencies, entrepreneurs, universities, and so on. These workshops performed the following activities:

-

Debating, challenging, and amending the GEDI analysis

-

Debating Scottish bottlenecks, as suggested by the GEDI analysis

-

Suggesting insights and perspectives from different parts of the Scottish entrepreneurship ecosystem

-

Suggesting follow-on analyses and data to further explore identified bottlenecks

-

Debating underlying causes for the bottlenecks

-

Identifying and prioritizing actions to alleviate the bottlenecks.

National Systems of Entrepreneurship are inherently complex. This means that no single individual or agency has complete information and insight as to how the system works. This also applies to the GEDI: Although it provides detailed insights, they are inevitably superficial. However, the GEDI also provides a coherent platform that helps focus the attention of various stakeholders and helps them take a system perspective when considering the trade-offs of alternative courses of action. A problem in many policy analyses is that they only provide a “siloed” view into a system—for example, by focusing on funding issues but ignoring other issues that may be linked to funding, which may prevent funding from having a positive impact on the system. The GEDI platform helps policymakers and policy stakeholders debate system issues that are outside their individual policy “silos.”

Because insight into what really makes the system work (or not) is distributed across different stakeholders, with no individual or agency having complete information, these insights need to be extracted from within the system. This is what the stakeholder engagement workshops have been designed to do. They use the “hard” facts of the GEDI to extract “soft” insights from within the system on issues that make a real difference. This process can contribute important insights. In Scotland, for example, the GEDI boilerplate analysis suggested that finance was a bottleneck for the Scottish entrepreneurship ecosystem. The stakeholder debates confirmed this and added important nuance—that is, that the supply of funding was not the real bottleneck. Various stakeholders pointed to the fact that equity investments had insufficient exit opportunities. Although equity funding as such was reasonably plentiful, the lack of liquidity meant that this funding got stuck in portfolio companies and was not recycled back to new investments.

More generally, the stakeholder workshops identified five priority themes and underlying causes: “financing for growth,” including exits for investors in angel-backed companies, which increased access to institutional and international funds; “effective connections,” which included networks but was more fundamental than networking; “skills for growth” for leadership teams within innovation-based research (IBE) ventures; “role of the universities in the IBE ecosystem”; and “role models and positive messages.” Chairs and other members of the stakeholder community were identified to participate in high-level task groups charged with implementing solutions to each of the five themes. Two task groups were formed for the universities theme, one internal to the universities and one external. These task forces have continued their work since the conclusion of the workshops, with mandates extending at least 1 year.

2.5 Summary

The above discussion suggests the following heuristic for using the Penalty for Bottleneck approach for policy analysis, design, and implementation:

-

1.

Identify bottleneck factors in the country’s National System of Entrepreneurship and compare these against relevant peers (i.e., countries at a similar level of economic development, with similar demographic conditions, and with similar levels of market size and market openness).

-

2.

Examine the bottleneck factors more closely, complementing GEDI indicators with alternative proxies.

-

3.

Conduct policy comparisons in bottleneck areas against relevant peers, with a focus on analyzing the anatomy of individual policy measures and identifying transferable good practices.

-

4.

Design and implement policy programs designed to alleviate bottleneck factors in the country, using the GEDI to help set targets for performance improvement.

Used this way, the GEDI could provide a helpful platform for implementing a systemic approach to entrepreneurship policy analysis, design, and implementation, one that focuses on improving the performance of National Systems of Entrepreneurship.

Notes

- 1.

See Chap. 5 for a detailed description of the GEDI method.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1988). Innovation in large and small firms. American Economic Review, 78, 678–690.

Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2013). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. ResearchPolicy. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733313001613.

Ahmad, N., & Hoffmann, A. (2008). A framework for addressing and measuring entrepreneurship. SSRN eLibrary.

Blanchflower, D. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labor Economics, 7, 471–505.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 453–517.

Edquist, C. (1997). National Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations. London: Pinter Publishers.

Gallup. (2009). Entrepreneurship in the EU and beyond. In E. D. E. A. Industry (Ed.), Flash Eurobarometer Series, Vol. 283. Brussels: European Commission.

International Social Survey Programme. (1997). Work orientations package II. Berlin: Leibniz Gemeinschaft.

Kirzner, I. (1997). Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 35, 60–85.

Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanisms of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22, 3–39.

Lunati, M., Meyer zu Schlochtern, J., & Sargsayan, G. (2010). Measuring entrepreneurship (15th ed., Vol. 15). Paris: OECD.

Lundvall, B.-Å. (Ed.). (1992). National systems of innovations. London: Pinter.

Lundvall, B. A. (1999). National business systems and national systems of innovation. International Studies of Business and Organization, 29, 60–77.

Nelson, R. R. (Ed.). (1993). National innovation systems: A comparative analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

OECD-Eurostat. (2007). Manual on business demography statistics. Paris: OECD.

Parker, S. C. (2009). The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reynolds, P. D., Bosma, N., & Autio, E. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation, 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24, 205–231.

Romer, P. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 71–102.

Solow, R. (1957). Technical progress and geh aggregate production function. Review of Economics and Statistics, 39, 312–320.

van Praag, M. C. (2007). What is the value of entrepreneurship research: A review of recent research. Small Business Economics, 29, 351–382.

World Bank. (2011). New business registration database. Washington, DC: Author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Acs, Z.J., Szerb, L., Autio, E. (2015). National Systems of Entrepreneurship. In: Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2014. SpringerBriefs in Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14932-5_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14932-5_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-14931-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-14932-5

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)