Abstract

South America harbors the highest plant diversity on Earth. The causes of such exceptionally high diversity remain poorly understood, despite great attention devoted to the ecology and evolution of biota in productive and geologically recent ecosystems such as the Amazon forest and the Andes. Evidence suggests ancient and extremely nutrient-poor landscapes are major centers of plant diversity and endemism, and acted as interglacial refugia, but singularities of their evolutionary history have been overlooked. Here, we examine to what extent Ocbil theory (old, climatically-buffered, infertile landscapes) may prove useful in explaining diversification patterns in some of the most diverse Neotropical ecosystems. We propose a theoretical framework that encompasses a mechanistic explanation for the predictions of Ocbil theory, and links ecological and evolutionary processes to vegetation patterns and functional traits. We review diversification patterns and population genetics in campos rupestres vegetation in light of Ocbil theory. We propose areas of future research that will accelerate and improve our understanding on the ecology and evolution of Neotropical biota on ancient, nutrient-poor vegetation. This knowledge is expected to shed light on the complex history of Neotropical plant diversification and, ultimately, provide tools for their sustainable use and conservation.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The Neotropical region holds the highest plant diversity in the world (Gentry 1982; Kier et al. 2005; Antonelli and Sanmartín 2011). The astounding Neotropical diversity has fascinated Europeans explorers and naturalists during early scientific exploration of the South American continent, and continues to wonder and puzzle present-day biologists (Antonelli and Sanmartín 2011; Antonelli et al. 2015). Despite such incredible high levels of diversity and endemism (Hughes et al. 2013), the mechanisms generating these patterns are not yet fully understood.

Much of the discussion of biogeographical gradients in species diversity has stemmed from the marked contrast between tropical versus temperate ecosystems (Pianka 1966). Pianka (1966) summarized six major theories (time, spatial heterogeneity, competition, predation, climatic stability, productivity) aiming to explain the latitudinal species gradient, but surprisingly, after for more than 50 years, there is yet no consensus on the factors driving species latitudinal gradients (Schemske and Mittelbach 2017). The fact that some temperate areas harbor higher diversity and endemism compared to some tropical ones (Cowling et al. 1996) suggests that additional overlooked factors may play a role in driving large-scale species diversity, or that the main six drivers may operate on other organizational scales, not only on a global one. In addition, the fact that adjacent areas at the same latitude may strongly differ in diversity and endemism patterns (Neves et al. 2018) reinforce the need of understanding the role of additional drivers of plant diversity and endemism (Fig. 14.1). With particular reference to the Neotropical regions, topography, soil adaptation, niche conservatism, and dispersal ability have been proposed as additional key drivers of continental-scale assembly of the biota (Antonelli and Sanmartín 2011), but the relative contribution of each driver remains elusive (but see Rangel et al. 2018).

Theoretical model explaining biogeographic assembly of Neotropical flora across scales (inspired by Götzenberger et al. 2012). Each box depicts one of the six classical drivers of diversity summarized by Pianka (1966). Lines indicate the role of each driver across each ecological scale. Red lines indicate the three dimensions of Ocbil theory, with time reflecting landscape age, productivity reflecting soil fertility and climatic stability reflecting climatic buffering (sensu Hopper 2009). The continental scale added here is included to provide complimentary explanations on why latitudinal species gradient do not always hold true and why different sites at the same latitude have contrasting diversities and endemism

Hopper (2009) developed Ocbil theory, an integrated set of principles to explain plant ecology and evolution in old, climatically-buffered, infertile landscapes (OCBILs). Ocbil theory proposes a series of testable hypotheses that span several levels of biological organization (from individuals to landscape), and helps explain why these ancient landscapes challenge patterns of latitudinal gradients with regard to species diversity and endemism. OCBILs are in the extreme end of a multivariate continuum of variation in landscape age, climatic fluctuation and soil fertility, whereas YODFELs (young, often-disturbed, fertile landscapes) stand at the other end of this eco-evolutionary continuum (Hopper et al. 2016).

Most of the theories underpinning modern Biology were generated in YODFELs (Hopper 2009), biasing the understanding of Neotropical vegetation and leading to detrimental consequences for the long-term conservation of these ancient, nutrient-poor vegetation types. A realistic example is the misunderstanding by some European and North American ecologists that grassy biomes are deforested land cleared by humans (Veldman et al. 2017). As a result, many ill-conceived policies have been advocated such as afforestation, despite clear evidence that planting trees in biodiverse grassy biomes will erode biodiversity and associated ecosystem services (Veldman et al. 2015). Gaining an evolutionary perspective into the assembly of OCBILs can help to clarify this misconception and provide strong arguments to improve conservation and restoration of extremely impoverished biodiversity hotspots (Dayrell et al. 2016).

Ocbil theory has gained recent traction by Neotropical plant biologists, plant ecologists, vegetation scientists and restoration ecologists, especially those studying vegetation types that fulfill the criteria for a classic OCBIL. Until July 2018, Hopper’s original paper (2009) has been cited by 21 studies in campos rupestres, 7 studies in inselbergs vegetation, 2 studies in tepuis and cangas each, and 1 in campos de altitude and southern grasslands each. Evidence supporting Ocbil theory is reviewed and discussed below for each of these vegetation types. Papers inspired by Ocbil theory addressed a broad of topics, ranging from population genetics (e.g. Hmeljevski et al. 2017b) to restoration ecology (e.g. Le Stradic et al. 2018), attesting the value of Ocbil theory to both theoretical and applied sciences (Morellato and Silveira 2018).

There are two main reasons why Ocbil theory is invoked to help explaining the community-scale assembly of Neotropical communities. First, it addresses factors that operate on a different scale than the classic Pianka’s drivers (Schemske and Mittelbach 2017; Fig. 14.1), thus providing complementary explanations for global patterns of species diversity and endemism. Second, significant fractions of the diversification of the Neotropical biota are related to the relatively recent Andean uplift in western South America (Antonelli et al. 2009; Rangel et al. 2018), but most Neotropical OCBILs are concentrated in eastern South America and are unlikely to have been strongly affected by the Andean uplift. Present-day floristic similarities between OCBILs and the Andes are relatively uncommon, suggesting limited biota interchange (Alves and Kolbek 2010).

In this chapter we examine to what extent Ocbil theory may prove useful in explaining diversification patterns in some of the most biodiverse Neotropical vegetation types. We developed a mechanistic explanation for the Ocbil theory by proposing a theoretical framework linking ecological and evolutionary processes to vegetation patterns. Next, we address the ecology and evolution of vegetation types that fulfill the criteria for a classic OCBIL. These vegetation types are amongst the least studied Neotropical ecosystems, despite emerging evidence suggesting they may be the most ancient (Hughes et al. 2013) and the most species-rich ones (BFG 2015) in South America. We scrutinize diversification predictions of Ocbil theory by critically reviewing the literature on diversification and population genetics in campos rupestres vegetation. Finally, we propose areas of future research that will accelerate and improve our understanding on the ecology and evolution of Neotropical biota on ancient, nutrient-poor vegetation. We expect this knowledge shed light on the complex history of Neotropical plant diversification.

2 Towards a Mechanistic Understanding of Ocbil Theory

Ocbil theory was conceived to better understand the origins, ecology and devise conservation strategies tailored for biodiversity on OCBILs. These ecosystems are particularly common in the Southern Hemisphere (Hopper 2009, 2018; Hopper et al. 2016) and remain largely unknown by most Northern Hemisphere plant scientists, ecologists and evolutionary biologists, who were born and educated in YODFELs. Two exceptions are the Southwestern Australia Floristic Region (SWAFR) and the Greater Cape Floristic Region (GCFR) in South Africa, which have received considerable attention, probably due to their Mediterranean-climate, enabling their comparisons with climatically similar ecosystems of the Northern Hemisphere (e.g. Cowling et al. 2015).

Ocbil theory proposes a series of testable hypotheses (see Table 14.1) that have inspired research and resonated with the ecology of some Neotropical OCBILs. However, since its original inception, Hopper (2009) recognized the need for more theoretical development of Ocbil theory, and the need for more quantitative assessments of these predictions (Hopper et al. 2016). Here, we provide a conceptual framework attempting to improve the mechanistic understanding of Ocbil theory by connecting the three drivers of diversity (old landscapes, infertile soils and buffered climates) with the expectations regarding diversification, vegetation patterns, and species functional traits (Fig. 14.2). Two original predictions, the Semiarid Cradle Hypothesis and adaptation to saline soils, can be expected only for the SWAFR, and were excluded from our framework. The recent natural hybridization hypothesis (Hopper 2018) was also excluded due to lack of available data in Neotropical vegetation. To expand the predictive power of Ocbil theory, we also included an additional prediction, the evolution of resource-conservation strategies, which we discuss below (Table 14.1). The dynamic and flexible nature of our conceptual framework accommodates the fact that some of the predicted patterns (see black boxes in Fig. 14.2) are not only determined by the three drivers of diversity, but can also indirectly provide feedback to other vegetation and trait expectations, thus playing dual roles in the framework (see gray arrows in Fig. 14.2).

A mechanistic framework showing the connections between three major edapho-climatic drivers of diversity (left panel boxes) and the predictions derived from Ocbil theory. These predictions result in a set of plant traits and vegetation patterns shown in the right panel boxes. The dashed arrow indicates that impoverished soils are the result of long-term physical and chemical weathering in some cases. Here, we expand the predictions of Ocbil theory by including an additional prediction that OCBIL plants have evolved a resource-conservation strategy in the red box (explained in the text). Our framework also allows positive feedbacks among plant traits and vegetation patterns (shown by gray arrows)

2.1 Driver-Pattern Feedbacks

Old landscapes, extremely-impoverished soils and buffered climate have been proposed to be the main drivers of diversification, vegetation patterns and species traits in a complex way (Hopper 2009; Table 14.1). Since the Cenozoic some areas of the world have remained relatively free from extreme geological and climatic events such as glaciation, mountain-building, volcanism, inundations, which has resulted in continuous physical and chemical weathering, causing marked decreases in nutrient availability such as Phosphorus (Lambers et al. 2008). In contrast, other areas had been recurrently exposed to these large-scale climatic and geologic disturbances, resulting in rejuvenated soils with increased levels of soil nutrients (Fig. 14.3).

Theoretical predictions of lineage diversification in Neotropical OCBILs (green panel and line) and YODFELs (red panel and line) (a) as a function of climatic and geological stability (b). The model begins with a YODFEL transitioning to an OCBIL as climatic stability increases and soil fertility decreases (overlapping area). Note that OCBILs are both museums (old lineages) and cradles (recent lineages), whereas YODFELs contain only recent lineages. Rates of extinction (graves) are higher in YODFELs and coincide with periods or disturbance. OCBILs are also biodiversity pumps generating lineages to adjacent lowland YODFELs. Note a high speciation rate during the Pleistocene indicated by a shaded area. Large-scale disturbance (indicated by arrows with different width) results in soil rejuvenation, increasing soil Phosphorus content. Extensive chemical and physical weathering in OCBILs results in loss of soil phosphorus generating extremely-impoverished soils. Throughout time species evolve different traits indicated by circles. Some traits are exclusive from each ecosystem (red, white and green circles), whereas others are common in both ecosystems, arising from a common ancestor with shifted ecosystem (yellow circle) or by convergent evolution (blue circles)

Mucina and Wardell-Johnson (2011) challenged the central tenets of Ocbil theory by identifying soil-impoverishment as a function of landscape age. It is undisputed that old soils are of low fertility, thus landscape age drives soil fertility to some extent (see the dashed arrow in Fig. 14.2). However, Schaefer et al. (2016) argue that some quarzitic bedrocks at the Espinhaço Range are intrinsically nutrient-poor. Therefore, soil fertility may be driven by long-term weathering, but this is not always the case (Walker and Syers 1976). As soil progressively becomes infertile, nutritional adaptations and biological specializations arise only in clades from OCBILs, whereas some traits likely evolve only in clades from YODFELs (e.g. traits selecting for long-distance seed dispersal) (Krüger et al. 2015; Oliveira et al. 2015; Zemunik et al. 2015; Turner et al. 2018).

Old lineages experienced prolonged speciation in ancient sites, where lower climatic fluctuations did not prompt diversification, and at the same time had decreased rates of species extinctions. In contrast, higher climatic fluctuations in YODFELs not only resulted in species extinction, but also created opportunities for diversification (Fig. 14.3). As a consequence of contrasting diversification dynamics in OCBILs versus YODFELs, ancient lineages (museums) occur only in the former, whereas recent lineages (cradles) occur in both sites (Hopper 2009).

More recent events, the Andean uplift in the Neogene and geomorphological changes during the Pliocene at the Espinhaço Range (Eastern Brazil; Saadi 1995), played a major role in diversification dynamics of Neotropical plants, which extended throughout South America (Antonelli et al. 2009; Potter and Szatmari 2009; Antonelli and Sanmartín 2011; Armijo et al. 2015; Rangel et al. 2018). It is expected that such pattern of rapid diversification may resulted in the evolution of similar functional traits in both OCBILs and YODFELs during the Quaternary (Fig. 14.3). This is supported by time-calibrated phylogenies showing recent and rapid diversification of lineages in both ecosystems (Richardson et al. 2001; Hughes and Eastwood 2006; Loeuille et al. 2015; Rando et al. 2016; Inglis and Cavalcanti 2018), but with exceptionally high diversification in the Andes (Madriñán et al. 2013). Persistence of old lineages, in turn, was only reported for OCBILs (Zappi et al. 2017; Alcântara et al. 2018).

2.2 The Interplay Between Patterns and Mechanisms

The combination of old landscapes, infertile soils and buffered climates leads to specific vegetation and trait patterns (see the black boxes in Fig. 14.2), but these can also influence and feedback one another. For instance, dispersal from parental habitat has high risks on OCBILs because plants are highly specialized to the rocky or sandy soils where they occur and are thus susceptible to physiological constraints that could limit growth in other habitat types (Porembski and Barthlott 2000; Jacobi et al. 2007; Poot et al. 2012; Silveira et al. 2016). Reduced dispersability is therefore a common strategy among OCBIL plants (Hopper et al. 2016; Fig. 14.2) that promotes divergence of local populations and allopatric speciation, and consequently contributes to increased endemism and common rarity (Hopper 2009; Echternacht et al. 2011; Silveira et al. 2016). The constraints in seed dispersal also limit population sizes and push towards mechanisms to conserve heterozygosity and escape from the deleterious effects of inbreeding.

Soil infertility, especially severe P-impoverishment, is a strong environmental filter that leads to a clear predominance of nutrient-conserving, slow-growing strategy (de Paula et al. 2015; Oliveira et al. 2015; Pierce et al. 2017; Fig. 14.5c). OCBILs are, therefore, mainly dominated by long-lived perennials that are able to survive and resprout after fire (Bond and Midgley 2001; Le Stradic et al. 2015). The great investment in persistent tissues in the nutrient conserving strategy may imply in relatively less investment in sexual reproduction (Bazzaz et al. 1987; Ehrlén and van Groenendael 1998; Gomes et al. 2018), often resulting either in a low seed set per individual (Stock et al. 1989), or in high proportion of seeds that lack embryos or are otherwise nonviable (Dayrell et al. 2016). The trade-off between nutrient-conservation and investment in sexual reproduction reinforces the vulnerability to soil removal, since OCBIL plants are not expected to have strategies for effective habitat recolonization. Old individuals appear to be consequences of the slow growth rate of plants (Negreiros et al. 2014; de Oliveira and Dickman 2017). The nutrient-poor soils are also associated with well-known nutritional specializations to efficiently capture and use soil nutrients (Lambers et al. 2010; Oliveira et al. 2015). It leads to further vulnerability to soil removal (Fig. 14.5f, g) because: (1) disturbances increases nutrients in the soil and these can be toxic for the plant (Barbosa et al. 2010); (2) disassociates species from the microhabitat they are extremely specialized in; (3) potentially alters the soil microbiota (Lambers et al. 2018).

Finally, natural selection in buffered climates and impoverished soils during millions of years favoured disjunct populations restricted to very specific soils in fine-scale mosaics with other soil types, resulting in fragmented population systems of many OCBIL plants. For this reason, these plants are also naturally resilient to fragmentation caused by human activities (Hopper 2009). The mechanisms OCBIL plants evolved to pursuit and conserve heterozygosity, including long-distance pollination (Fig. 14.5e), should also help population persistence in the face of fragmentation by maintaining the flow of nuclear genes in these taxa (Fig. 14.2).

3 Plant Diversity and Endemism in Neotropical Ocbils: The Untold History of Ancient and Nutrient-Poor South American Vegetation

Hopper (2009) originally included three sites as classic OCBILs, but anticipated the existence of many other candidates across the southern hemisphere. The three original OCBILs were the SWAFR, GCFR, and the tepuis in northern South America. More recently, Hopper et al. (2016) identified significant areas covered by OCBILs in at least 12 biodiversity hotspots around the globe, concentrated, but not limited to the southern hemisphere (Fig. 14.4). Altogether the tepuis, campos rupestres, SWAFR and GCFR cover only 0.27% of Earth’s land surface (Hopper 2009; Silveira et al. 2016), yet are home to 7.7% of the known vascular plant diversity (Christenhusz and Byng 2016).

Typical landscape of Neotropical Ocbils include the campos rupestres (a, b), vegetation on ironstone outcrops (cangas) (c, d), Inselbergs (e, f), and campos de altitude (g, h). Note the sky islands distribution across all vegetation types in Bahia (b), Espírito Santo (e) and Rio de Janeiro states (h). Individuals of Vellozia are shown in a dehydrated state (c) and on flowering (d). Pictures a, b, d, g, h—Augusto Gomes, c—Luiza C. Martins, e, f—Luiza de Paula

In the Neotropics, classic OCBILs are represented by the tepuis, campos rupestres, cangas, campos de altitude and inselbergs (Fig. 14.4). The tepuis are famous worldwide even outside the scientific literature, with the publication of “The Lost World” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Conan Doyle 1912). However, the other four ecosystems have not enjoyed the same level of recognition. All five ecosystems share and fulfill to varying extents the criteria for being included as OCBILs, occurring at the extreme of old geological age, climatic stability, and soil infertility. Below, we describe features of these vegetation types, although we recognize that many other vegetation types (e.g. subtropical highland grasslands; Iganci et al. 2011) and white-sand ecosystems in throughout Amazonia (Adeney et al. 2016) may also fit the criteria for inclusion in Ocbil theory to some extent. Our focus is on diversification patterns, but we also discuss vegetation patterns and plant traits predicted by Ocbil theory (Table 14.2).

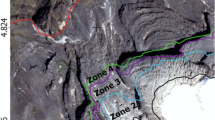

Two additional key geographic and geomorphologic characteristics are shared by all Neotropical OCBILs. First, all five Neotropical OCBILs are associated with rocky outcrops. Rocky outcrops are often long-lasting landscape features with stable micro-climates and constitute ecological refuges (Fitzsimons and Michael 2017). Also, populations growing on rocky outcrops with different geology and mineralogy may be genetically differentiated (Borba et al. 2001a; Lousada et al. 2013; Leles et al. 2015). At the community-level, there are clear differences in species composition and distribution of plant traits among different rock outcrop types (Carmo and Jacobi 2016; Carmo et al. 2016). The tepuis and the campos rupestres are of quartzite and/or sandstone geology, cangas occur on ironstone outcrops (mostly banded iron formations), and inselbergs and campos de altitude on granitoids.

The second characteristic is that all of them can fit the definition of sky islands (isolated mountaintops surrounded by drastically different lowland environments; McCormack et al. 2009). This raises the question on whether Ocbil theory should be invoked to explain the high species diversity and endemism in these ecosystems, since mountains per se outside polar regions and deserts are home to an exceptional biodiversity and high levels of endemism regardless of landscape age and soil fertility (Colwell et al. 2008; Steinbauer et al. 2016; Hoorn et al. 2018). There are marked genetic differentiations in populations growing on different sky islands (Pinheiro et al. 2011), so these ecosystems are excellent models to study species diversification, which is discussed in the next section.

Neotropical OCBILs are represented by grassy-shrub, open vegetation usually associated with outcrops of different origin. The campos rupestres and campos de altitude are fire-prone ecosystems, although human-caused fires may occur on cangas and inselbergs occasionally. Neotropical OCBILs often occur on some of the most spectacular landforms and landscapes of eastern South America, often on mountains that are spatially distributed as terrestrial islands (Fig. 14.4). Such landscape is better described as a mosaic of islands of ancient climatically-buffered, infertile highlands immersed in a matrix of relatively recent and fertile landscapes. Typical Neotropical OCBILs discussed include the tepuis (scattered throughout the Amazon forest), campos rupestres (immersed in the Atlantic Rain Forest, Cerrado and Caatinga biomes), on ironstone outcrops such as the cangas (in Central Amazon, Cerrado and Atlantic Forest) and on granitic-gneissic outcrops such as inselbergs and the campos de altitude (embedded in Caatinga and the Atlantic Rain Forest biomes). They all cover diminutive geographic areas, but host disproportionately high levels of diversity and endemism (Safford 1999a; Porembski 2000; Jacobi et al. 2007; Silveira et al. 2016).

The geological origin of banded iron formations, quartzite and granitic outcrops in Eastern South America dates back to the Precambrian with dates ranging from 2.5 Ga to a few hundred million years (Twidale 1982; Klein 2005; Gradim et al. 2014; Vieira et al. 2015). Throughout late Proterozoic and the Phanerozoic, long-term chemical and physical weathering denudated such landscapes (Barreto et al. 2013), creating snow-free mountains ranging in altitudes from 900 to 2020 m above sea level. This suggests that their present-day altitudes are only a fraction of what they once were (Safford 1999b). This ancient geological origin has set the scene for the establishment of the some of the oldest open vegetation types in Eastern South America (Hughes et al. 2013; Zappi et al. 2017).

The ancient origin of OCBILs markedly contrasts with the recent Andean uplift during the Neogene and diversification of lineages associated with the geomorphological and hydrological changes in Western South America. These recent changes have been extensive documented and explored (Antonelli et al. 2009), but the evolutionary and ecological history of Neotropical OCBILs is not well understood. Below, we discuss these issues for four typical vegetation types that are centers of diversity and endemism (Fig. 14.4). For the ecology and evolution of the tepuis, a fifth typical OCBIL, refer to Rull (2005, 2009).

3.1 Campos Rupestres

Campos rupestres (or rupestrian grasslands) is defined as a montane, grassy-shrubby, fire-prone vegetation mosaic with outcrops of quartzite or sandstone, along with sandy, stony, and waterlogged grasslands. Patches of transitional vegetation such as cerrado, gallery forests, and relictual hilltop forests are also within the sensu lato definition of campos rupestres (Silveira et al. 2016; Morellato and Silveira 2018). Campos rupestres vegetation dominates the highest elevation sites at the Espinhaço Range, the third largest mountain chain in South America. The Espinhaço Range is bordered on the eastern slopes by the Atlantic Rain Forest, on the western slopes by the Cerrado, and on the northern slopes by the Caatinga (see map in Morellato and Silveira 2018). However, isolated sites also occur in central and southern Brazil, central Amazonia, northeastern Brazil, and eastern Bolivia. Despite occupying an area smaller than 0.8% of Brazil, campos rupestres host nearly 15% of plant diversity in the country (Silveira et al. 2016). Endemism in campos rupestres is nearly 40%, the highest among Brazilian vegetation types (BFG 2015).

The acknowledgment of campos rupestres’ exceptionally high diversity, endemism, and typical harsh environment has emerged only recently (Fernandes 2016; but see Giulietti et al. 1997), and the causes of such diversity are still being debated. Nevertheless, studies on population genetics in campos rupestres species are relatively common (see Sect. 4). While the prediction of persistence of old lineages (the Gondwanan heritage hypothesis) has been supported by literature (see reviews in Silveira et al. 2016; Zappi et al. 2017; Alcântara et al. 2018), recent diversification of some lineages also indicates the campos rupestres as cradles of endemic lineages (e.g. Ribeiro et al. 2013; Loeuille et al. 2015; Rando et al. 2016; Inglis and Cavalcanti 2018). Unfortunately, there are few time-calibrated trees for campos rupestres lineages, and those available do not focus on the most diverse and dominant clades.

3.2 Vegetation on Cangas

Vegetation growing on ironstone outcrops (locally known as cangas), are geologically, pedologically, structurally, floristically and functionally different from previously identified quartzitic and sandstone campos rupestres (Mucina 2018). Therefore, vegetation establishing on ironstone outcrops is treated here separately from the campos rupestres (sensu Silveira et al. 2016). Ironstone outcrops originate from Precambrian deposits (Klein 2005) and constitute some of the world’s most important sites of iron ore mining. In Brazil they are best represented by sites at the Iron Quadrangle in southeastern Brazil (Jacobi et al. 2007) and the Carajás Range in eastern Amazon (Viana et al. 2016), but small patches are found elsewhere (Carmo and Kamino 2015).

Ironstone outcrops share most of the characteristics of other outcrops, such as isolation and edapho-climatic harshness, but differ in that they metal-rich substrates targeted for extensive and rapidly increasing opencast mining, and thus subjected to irrecoverable degradation (Jacobi et al. 2007). Iron caves are singular habitats that are extremely sensitive to human impacts (Jaffé et al. 2018). Vegetation on cangas is recognized as centers of diversity and endemism, with southeastern Brazil hosting nearly 3000 species (Carmo et al. 2018). Species establishing on cangas show adaptations to heavy metals in the soils (Jacobi et al. 2007), but their ecology is poorly understood (Giannini et al. 2017; Lanes et al. 2018).

Population genetic studies on a cangas endemic and threatened bromeliad suggest that heterozygosity is lower than expected due to selfing or biparental inbreeding and that low genetic differentiation probably results from long distance pollination by hummingbirds (Lavor et al. 2014). However, knowledge on diversification patterns in cangas is virtually unknown.

3.3 Campos de Altitude

Campos de altitude (or high-altitude grasslands) are a series of cool-humid, grass-dominated formations restricted to the highest summits of the Serra da Mantiqueira and Serra do Mar Range, the second largest mountain range in South America, only to the Andes (Safford 1999a). The Serra do Mar Range stretches along the Atlantic Coast fully immersed within the Atlantic Rain Forest biome, and campos de altitude are found exclusively on uplifted blocks of igneous or high-grade metamorphic rocks, ranging from Archean gneisses to Late Proterozoic granites and granitoid gneisses (Safford 1999a). The campos de altitude has been present on highest summits (from 1800 to 2000 m upwards) from at least since the Late Pleistocene and occupies an area of only 350 km2 in the present-day (Safford 1999a).

The flora of the campos de altitude is highly diverse and characterized by a high degree of endemism, and has stronger floristic similarities (at least at genus-level) with the flora established on the equatorial alpine formations of the Andean and Central American Cordillera; these similarities also extend to climate, soils, and landscapes (Safford 1999a, b; Alves and Kolbek 2010). Macroclimatic similarities between the Andes and the Serra do Mar Range may form the basis for the strong biogeographic connections, and the context within which evolutionary and ecological parallelisms shaped the biota of these two widely separated Neotropical mountains (Safford 1999b). Ancient elements of the flora are represented by Gondwanan-heritage lineages such as Velloziaceae, Eriocaulaceae and Xyridaceae. Pollination by long-distance pollinators such as hummingbirds is not high as predicted by the James effect hypotheses (Freitas and Sazima 2006).

3.4 Inselbergs

Inselbergs, or granitic and gneissic monolithic rock outcrops are emblematic examples of ancient, nutrient-poor ecosystems that are scattered across the Neotropics (Porembski et al. 1997; Porembski 2000; Scarano 2002; Neves et al. 2017). Inselbergs rise abruptly above the surrounding lowland landscape as sky islands. These outcrops are found embedded in a matrix of Amazon forest (Sarthou et al. 2017; Villa et al. 2018), Atlantic Rain Forest (de Paula et al. 2016), Caatinga (Silva et al. 2018), and the southern grasslands (Carlucci et al. 2015). They fulfill many criteria of Ocbil theory, with their geological dating back to the Precambrian (Twidale 1982), and their prevailing stressful conditions including shallow (or absent), nutrient-poor soils, water stress, high temperatures and constant winds (Porembski 2000; Scarano 2002; de Paula et al. 2015).

Inselbergs harbor a highly diverse, endemic and threatened flora (Porembski 2000, 2007; Porembski et al. 2016). The spatial configuration of terrestrial islands is likely the cause of high beta diversity among inselbergs, with species turnover being the major driver of changes in species composition (Martinelli 1989; Sarthou et al. 2017). Inselbergs are centers of endemism for several plant clades, but especially for Bromeliaceae (de Paula et al. 2016). The origin and diversification of this Neotropical dominant family is associated with rocky outcrop formation in the tepuis and southeastern Brazil (Givnish et al. 2014; Gomes-da-Silva et al. 2017).

To date several studies have addressed population genetics, reproductive ecology, phylogeography and radiation in inselbergs endemics (e.g. Barbará et al. 2008, 2009; Palma-Silva et al. 2011; Pinheiro et al. 2014). Pollination by long-distance pollinators (large bees, bats and hummingbirds), short seed dispersal distances, high genetic differentiation and structure, low genetic connectivity and long-term persistence of populations emerge as ubiquitous patterns (e.g. Paggi et al. 2010; Hmeljevski et al. 2017a, b). The sky islands of inselbergs also isolate populations on inselbergs summits. Some of these studies have explicitly tested the idea of dispersal limitation by comparing population genetic structure from nuclear genes (mediated by pollen dispersal) and chloroplast markers (mediated by seed dispersal). Some studies have found higher genetic structure from cpDNA (plastid DNA) compared to nuclear DNA (Hmeljevski et al. 2017a, b), therefore suggesting seed dispersal is much more limited than pollen dispersal (Sarthou et al. 2001) and providing indirect support for Ocbil theory in inselbergs endemics. Nevertheless, most studies on inselbergs plants are restricted to bromeliads and orchids (but see Duputié et al. 2009), limiting our ability to draw general conclusions for inselbergs vegetation.

4 Diversification and Population Genetics in Campos Rupestres

Island-like environments are recognized as cradles for endemic plants, due to (1) restricted gene flow between populations, followed by speciation by genetic drift, or (2) distinct selective pressures, leading to speciation by local adaptation (Kier et al. 2009; Stuessy et al. 2014; Crawford and Archibald 2017). Besides geographic isolation, elevation is also positively correlated to an increase in endemism, due to topography-driven isolation (Steinbauer et al. 2016). In a seminal work, Giulietti and Pirani (1988) suggested that the disjunct distribution of the campos rupestres leads to disjunct population distribution of its plant species, especially the rupicolous ones, potentially constituting one of the main engines to the great plant diversity and high endemism observed in this ecosystem. Here we summarize some of the findings of population genetics studies investigating this hypothesis.

In the campos rupestres and other Neotropical island-like OCBILs, the barrier to gene flow imposed by the matrix is strong, because plants would be physiologically constrained by their high specialization to the rock or sandy soils (Porembski and Barthlott 2000; Jacobi et al. 2007; Poot et al. 2012; Silveira et al. 2016). It has also been proposed that in this environment the lineages persist in loco for long periods of time, since it is expected that the climate is buffered and that physical characteristics of the outcrops allow the maintenance of stable microhabitats during climatic oscillation (Main 1997; Hopper 2009; Silveira et al. 2016). Indeed, simulations indicate that outcrop flora remains in local refugia during drier climate periods (Schut et al. 2014). All these factors are expected to lead to population systems with prolonged independent evolution and higher coalescence times than the observed in naturally less fragmented landscapes, as observed in OCBILs in Australia (Byrne and Hopper 2008; Tapper et al. 2014a, b). Differently from the vegetation of lowland Neotropical forests and savannas, which are alternative stable states maintained mainly by vegetation-fire feedbacks (Murphy and Bowman 2012), the soil-specialized vegetation of campos rupestres is not expected to expand significantly out of the geographical limits of the outcrops and sandy soils during climatic oscillations, sporadically becoming more continuous. However, it is expected that the populations could suffer demographic changes during climatic oscillations, as population sizes are not strictly linked to geographical range sizes and migration could be affected by matrix characteristics (Barbosa et al. 2015).

The first genetic studies testing the hypothesis by Giulietti and Pirani (1988) began only in the twenty-first century, which found very divergent results regarding genetic diversity and structuring between species of orchids (Borba et al. 2001a) and Asteraceae (Jesus et al. 2001). Since then, genetic diversity of populations of more than 80 campos rupestres plants species have been evaluated (Table 14.3). Allozymes were the more frequent marker employed, representing nearly 60% of all studies. Sequencing of nuclear and plastid regions, RAPD, SSR, and ISSR were also a source of information. The geographical distribution of these species covered all the latitudinal distribution of the campos rupestres, but there was a strong focus in some groups such as Orchidaceae (24 species, Fig. 14.5a, b), Fabaceae and Cactaceae (14 each) and Asteraceae (10 species). Bromeliaceae and Apocynaceae (6 species each), Eriocaulaceae and Velloziaceae (5), Melastomataceae (1) and Polygonaceae (1) were also studied (Table 14.3).

Flowers of fly-pollinated orchids (Bulbophyllum perii, a and Bulbophyllum exaltatum, b) from campos rupestres. Young seedling of Pleroma (Melastomataceae) established directly on a granitic outcrop showing a developed aquiferous pith related to water conservation (c). Dry capsules of Lavoisiera subulata (Melastomataceae) showing fruits with no obvious mechanisms for seed dispersal (d). Hummingbird-pollinated flowers of the mistletoe Psittacanthus robustus (Loranthaceae) (e). Lack of spontaneous natural regeneration following soil removal due to road building in campos rupestres (f) and surface iron ore mining in cangas (g). Pictures a, b—Cecília Fiorini, c—Luiza de Paula, d, f—Fernando Silveira, e—Tadeu Guerra, g—Lucas Perillo

Campos rupestres species showed either low or high intra-population genetic diversity, with only a few species showing regular levels (meaning close to the average observed for different markers in plants; refer to Hamrick and Godt 1990, 1996; Nybom 2004) (Table 14.3). Narrowly distributed taxa show lower levels of variation in some comparisons with congenerics, but definitive conclusions cannot be drawn since studies on rare endemics or endangered species did not concentrate on taxa with lower levels of genetic diversity (Franceschinelli et al. 2006; da Silva et al. 2007). Some endangered species also present low intrapopulation genetic diversity (e.g. Lambert et al. 2006a, b; Pereira et al. 2007; Jesus et al. 2009), what would be expected for species with small populations threatened by human activities. In addition, some studies that showed lower levels of genetic diversity point out to limitations inherent to the markers as one possible masking factor for this pattern. Generally, species of Orchidaceae showed high values of genetic diversity, while species in Asteraceae, Eriocaulaceae, and Fabaceae generally presented lower values. These trends have been tentatively explained by life-history traits, mating systems, demography, and ecological characteristics, but unfortunately, data on more species are still not available to test these hypotheses.

The population genetics of campos rupestres species corroborates that gene flow between populations is limited. Twenty-four out of 60 studies where population differentiation was evaluated (Table 14.3) showed high fixation index (F ST), giving support to the hypothesis that the huge diversity of species, especially of endemics, observed in the campos rupestres is generated due to limited gene flow among populations. From the 23 studies that showed low levels of differentiation, 14 encompassed endemics with narrow geographic distributions. In addition, low genetic differentiation between populations may be related to ancestral polymorphisms due to limited marker variability, mainly in allozymes. For example, Borba et al. (2001a) pointed out that some close areas possess exclusive alleles, despite the overall similarity between populations, indicating that this similarity could be an artifact of the marker resolution.

Campos rupestres plants from distinct families exhibited greater genetic structuring in plastid markers compared to nuclear markers, as a result of lower gene flow by seed dispersal than by pollen dispersal (Barbosa 2011; Palma-Silva et al. 2011; Pinheiro et al. 2014). Even in the presence of pollen flow, isolation due to low seed dispersal may lead to conflicts between nuclear and plastid genes, and consequent reproductive isolation and speciation (Greiner et al. 2011; Greiner and Bock 2013; Barnard-Kubow et al. 2016). Studies investigating speciation by gene conflict (Crespi and Nosil 2013) should be performed to examine the extension of their commonality in OCBILs.

Isolation by distance (IBD) was found in 18 of the 42 taxa tested (Table 14.3). IBD was more common in species with smaller geographic distributions, suggesting that long distances restrict plant species gene flow in campos rupestres. For some species, even on short distances, there were no signs of IBD, indicating stochastic colonization of the patches. However, some cacti showed IBD, despite their broad or medium distributions. This could be related to seed and pollen dispersion strategies (Bonatelli et al. 2014). One Asteraceae species with intermediate geographic distribution also showed evidence of IBD, but data may have been influenced by two populations that are highly isolated from the species core area (Jesus et al. 2001).

The population genetics studies in campos rupestres show that the disjunct distribution of this environment is an important factor in the diversification of its species. This pattern could be expected for species with traits leading to low dispersability, such as seeds of dry fruits without adaptations for anemochory (e.g. Fig. 14.5d) and flowers pollinated by small insects, or animals presenting optimal foraging behavior (e.g. social bees and territorialist hummingbirds). The presence of such traits has been invoked as justifying the high genetic structuring in species of some plant groups, such as Velloziaceae (Franceschinelli et al. 2006; Lousada et al. 2011, 2013; Barbosa et al. 2012), Eriocaulaceae (Pereira et al. 2007; Ribeiro et al. 2018), and some Asteraceae (Jesus et al. 2001, 2009; Collevatti et al. 2009). The data presented by these studies support the hypothesis of low dispersability as a characteristic of the plant species in OCBILs, particularly expected in environments such as campos rupestres, with the occurrence of populations clearly delimited in small areas, due to local peculiarities of characteristics of sandy soils and small, isolated outcrops.

The moderate to high genetic structuring observed in some species of Orchidaceae would not be expected, at least theoretically (e.g. Azevedo et al. 2007; Borba et al. 2001a, b, 2007a, b; Ribeiro et al. 2008; da Cruz et al. 2011; Leal et al. 2016). Orchid seeds are among the smallest and lightest in plants, and can travel hundreds of kilometers by the action of the wind (Arditti and Ghani 2000). However, the absence of individuals in rocky outcrops nearby established populations (a few tens or hundreds of meters), and apparently very similar to outcrops with large populations of the same species is remarkable. We suggest that in these cases the potential of physical dispersal of these seeds is not a good indicator of effective dispersal (considering seed germinability and seedling establishment; Schupp et al. 2010), probably due to small variations in physical, chemical and biological characteristics (in the case of orchids, occurrence of symbiotic mycorrhizae) of the substrate. Unfortunately, no study has been conducted so far to test this hypothesis.

Future studies might make an effort to achieve better resolution about the gene flow dynamics by using more powerful markers and analysis (Bertorelle et al. 2010; Ellegren 2014; Andrews et al. 2016), bearing in mind the need for careful sampling to avoid spurious patterns of genetic structure. We also emphasize the need to encourage the development of studies determining the effective dispersal and its restrictions in the different groups of plants, especially in those presenting both significant genetic structuring and characteristics that would not favor such structuring, such as pollination by birds and bats (e.g. Bromeliaceae) and long-distance seed dispersal by wind (e.g. Orchidaceae).

As generally campos rupestres plant species show a pattern of high population differentiation, a better understanding of campos rupestres species life-history and demography is fundamental for their conservation. In population systems where the genetic variability is structured, as occurs in the campos rupestres, the loss of a single population could have a great impact on total species diversity and may compromise its conservation. Besides, as an island-like environment, campos rupestres also offer opportunities for the study of the evolution of species and a better comprehension of differentiation processes.

5 Conclusions

Here, we argued that Ocbil theory is useful for explaining diversification, vegetation patterns and functional traits in old, climatically-buffered and infertile landscapes. Notably, all Neotropical OCBILs overlap with montane areas and their geographic distribution can be described as sky islands. Sky island theory plays a role in structuring species and genetic diversity in these four ecosystems, but it does not aim to explain the evolution of functional traits related to resource acquisition and conservation. Therefore, we contend that Ocbil theory and sky island theory both are useful for explaining plant ecology and evolution in South America’s most ancient and infertile soils.

The four examples presented here—campos rupestres, cangas, inselbergs and campos de altitude—illustrate ecosystems which occupy a diminutive area, yet harbor exceptionally high diversity and endemism. Compared to Australian, European and North American ecosystems, the study of ecology and evolution of Neotropical OCBILs is still in the first development steps. However, the results that we already have show an astonishing opportunity for a better understanding of the drivers of biological diversification. These ecosystems are excellent models to study speciation, diversification and evolution, and should be given special conservation priority. Bringing ancient, nutrient-poor open vegetation to the forefront of Neotropical plant biologists is critical to increase awareness of their conservation and restoration (Fiedler 2015; Overbeck et al. 2015; Veldman et al. 2015, 2017; Morellato and Silveira 2018). Some of these ecosystems are among the most threatened by human-impact (Fernandes et al. 2018) and we run the risk of rapidly losing an irreplaceable evolutionary history. Such understanding is not only important to reconstruct the complex biogeography of the Neotropics, but also is vital for sustaining ecosystem services (Fernandes et al. 2018; Pontara et al. 2018).

5.1 Areas of Future Research

Despite recent developments and progress towards the understanding of the ecology and evolution of biota in OCBILs, opportunities for future investigation remain vast. Moving from qualitative to quantitative assessments of ecosystem properties would provide robust evidence to test the predictions of Ocbil theory. Available evidence supports the campos rupestres and inselbergs as classic OCBILs, but more research is needed on the diversification patterns and species traits in cangas vegetation and campos de altitude in order to determine their position in the OCBIL-YODFEL multivariate continuum (Table 14.2).

Particularly, we need to move from indirect to direct indicators of diversification, vegetation patterns and functional traits. We call for further measurements of both pollen and seed deposition patterns under field conditions (Schupp et al. 2010), quantitative meta-analyses of diversification patterns (e.g. Madriñán et al. 2013), controlled experiments determining the effectiveness of root specializations (Güsewell and Schroth 2017), and long-term assessments of the impacts of soil removal and habitat fragmentation. Such data will be important to support the development of empirical quantitative modeling. We should also have a better appreciation on the role played by habitat heterogeneity in determining species diversity (Schemske and Mittelbach 2017), which is not addressed extensively by Ocbil theory.

The recent developments in sequencing technologies and the progressive increase in computer power are also offering us an unseen capability of evaluating past biological dynamics on non-model organisms with more resolution and accuracy (Ellegren 2014). Many of the 50 fundamental questions about island biology proposed by Patiño et al. (2017) could be answered in the context of the Neotropical OCBILs with molecular tools, boosting the understanding of this field in a context still little explored. Researchers studying Neotropical OCBILs should take advantage of these to better explore evolutionary hypotheses and shed light on the exciting life on OCBILs.

The pervasive bias in the ecological literature towards young and fertile environments (Martin et al. 2012) has prevented the evolution of a theoretical framework for Gondwanan vegetation. We contend that theory of plant ecology and evolution in the Neotropics needs to challenge pre-established paradigms and offer fresh perspectives that can be derived by Ocbil theory.

References

Adeney JM, Christensen NL, Vicentini A, Cohn-Haft M (2016) White-sand ecosystems in Amazonia. Biotropica 48:7–23

Alcântara S, Ree RH, Mello-Silva R (2018) Accelerated diversification and functional trait evolution in Velloziaceae reveal new insights into the origins of the campos rupestres’ exceptional floristic richness. Ann Bot 122:165–180

Alves RVJ, Kolbek J (2010) Can campo rupestre vegetation be floristically delimited based on vascular plant genera? Plant Ecol 207:67–79

Andrews KR, Good JM, Miller MR, Luikart G, Hohenlohe PA (2016) Harnessing the power of RADseq for ecological and evolutionary genomics. Nat Rev Genet 17:81–93

Antonelli A, Sanmartín I (2011) Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60:403–414

Antonelli A, Nylander JA, Persson C, Sanmartín I (2009) Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on Neotropical plant evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9749–9754

Antonelli A, Zizka A, Silvestro D, Scharn R, Cascales-Miñana B, Bacon CD (2015) An engine for global plant diversity: highest evolutionary turnover and emigration in the American tropics. Front Genet 6(130). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2015.00130

Arditti J, Ghani AKA (2000) Numerical and physical properties of orchid seeds and their biological implications. New Phytol 145:367–421

Armijo R, Lacassin R, Coudurier-Curveur A, Carrizo D (2015) Coupled tectonic evolution of Andean orogeny and global climate. Earth-Sci Rev 143:1–35

Azevedo CO, Borba EL, van den Berg C (2006) Evidence of natural hybridization and introgression in Bulbophyllum involutum Borba, Semir & F. Barros and B. weddellii (Lindl.) Rchb. f. (Orchidaceae) in the Chapada Diamantina, Brazil, by using allozyme markers. Braz J Bot 29:415–421

Azevedo MTA, Borba EL, Semir J, Solferini VN (2007) High genetic variability in Neotropical myophilous orchids. Bot J Linn Soc 153:33–40

Barbará T, Lexer C, Martinelli G, Mayo S, Fay MF, Heuertz M (2008) Within-population spatial genetic structure in four naturally fragmented species of a neotropical inselberg radiation, Alcantarea imperialis, A. geniculata, A. glaziouana and A. regina (Bromeliaceae). Heredity 101:285–296

Barbará T, Martinelli G, Palma-Silva C, Fay MF, Mayo S, Lexer C (2009) Genetic relationships and variation in reproductive strategies in four closely related bromeliads adapted to neotropical ‘inselbergs’: Alcantarea glaziouana, A. regina, A. geniculata and A. imperialis (Bromeliaceae). Ann Bot 103:65–77

Barbosa AR (2011) Biossistemática do complexo Vellozia hirsuta (Velloziaceae) baseada em análise filogeográfica e genética de populações. MSc Dissertation, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

Barbosa NPU, Fernandes GW, Carneiro MAA, Júnior LA (2010) Distribution of non-native invasive species and soil properties in proximity to paved roads and unpaved roads in a quartzitic mountainous grassland of southeastern Brazil (rupestrian fields). Biol Invasions 12:3745–3755

Barbosa AR, Fiorini CF, Silva-Pereira V, Mello-Silva R, Borba EL (2012) Geographical genetic structuring and phenotypic variation in the Vellozia hirsuta (Velloziaceae) ochlospecies complex. Am J Bot 99:1477–1488

Barbosa NPU, Fernandes GW, Sanchez-Azofeifa A (2015) A relict species restricted to a quartzitic mountain in tropical America: an example of microrefugium? Acta Bot Bras 29:299–309

Barnard-Kubow KB, So N, Galloway LF (2016) Cytonuclear incompatibility contributes to the early stages of speciation. Evolution 70:2752–2766

Barreto HN, Varajão CA, Braucher R, Bourlès DL, Salgado AA, Varajão AF (2013) Denudation rates of the Southern Espinhaço Range, Minas Gerais, Brazil, determined by in situ-produced cosmogenic beryllium-10. Geomorphology 191:1–13

Bazzaz FA, Chiariello NR, Coley PD, Pitelka LF (1987) Allocating resources to reproduction and defense. Bioscience 37:58–67

Bertorelle G, Benazzo A, Mona S (2010) ABC as a flexible framework to estimate demography over space and time: some cons, many pros. Mol Ecol 19:2609–2625

BFG (2015) Growing knowledge: an overview of Seed Plant diversity in Brazil. Rodriguésia 66:1085–1113

Bonatelli IA, Perez MF, Peterson AT, Taylor NP, Zappi DC, Machado MC, Koch I, Pires AHC, Moraes EM (2014) Interglacial microrefugia and diversification of a cactus species complex: phylogeography and palaeodistributional reconstructions for Pilosocereus aurisetus and allies. Mol Ecol 23:3044–3063

Bond WJ, Midgley JJ (2001) Ecology of sprouting in woody plants: the persistence niche. Trends Ecol Evol 16:45–51

Borba EL, Felix JM, Semir J, Solferini VN (2000) Pleurothallis fabiobarrosii, a new Brazilian species: morphological and genetic data with notes on the taxonomy of Brazilian rupicolous Pleurothallis. Lindleyana 15:2–9

Borba EL, Felix JM, Solferini VN, Semir J (2001a) Fly-pollinated Pleurothallis (Orchidaceae) species have high genetic variability: evidence from isozyme markers. Am J Bot 88:419–428

Borba EL, Trigo JR, Semir J (2001b) Variation of diastereoisomeric pyrrolizidine alkaloids in Pleurothallis (Orchidaceae). Biochem Syst Ecol 29:45–52

Borba EL, Funch RR, Ribeiro PL, Smidt EC, Silva-Pereira V (2007a) Demography, and genetic and morphological variability of the endangered Sophronitis sincorana (Orchidaceae) in the Chapada Diamantina, Brazil. Plant Syst Evol 267:129–146

Borba EL, Funch RR, Ribeiro PL, Smidt EC, Silva-Pereira V (2007b) Demografia, variabilidade genética e morfológica e conservação de Cattleya tenuis (Orchidaceae), espécie ameaçada de extinção da Chapada Diamantina. Sitientibus Ser Ci Biol 7:211–222

Byrne M, Hopper SD (2008) Granite outcrops as ancient islands in old landscapes: evidence from the phylogeography and population genetics of Eucalyptus caesia (Myrtaceae) in Western Australia. Biol J Linn Soc 93(1):177–188

Carlucci MB, Bastazini VA, Hofmann GS, de Macedo JH, Iob G, Duarte LD, Hartz S, Müller SC (2015) Taxonomic and functional diversity of woody plant communities on opposing slopes of inselbergs in southern Brazil. Plant Ecol Divers 8:187–197

Carmo FF, Jacobi CM (2016) Diversity and plant trait-soil relationships among rock outcrops in the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest. Plant Soil 403:7–20

Carmo FF, Kamino LHY (2015) Geossistemas ferruginosos do Brasil: áreas prioritárias para conservação da diversidade geológica e biológica, patrimônio cultural e serviços ambientais. 3i Editora, Belo Horizonte

Carmo FF, de Campos IC, Jacobi CM (2016) Effects of fine-scale surface heterogeneity on rock outcrop plant community structure. J Veg Sci 27:50–59

Carmo FF, da Mota RC, Kamino LHY, Jacobi CM (2018) Check-list of vascular plant communities on ironstone ranges of south-eastern Brazil: dataset for conservation. Biodiv Data J 6:e27032. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.6.e27032

Cavallari MM, Forzza RC, Veasey EA, Zucchi MI, Oliveira GCX (2006) Genetic variation in three endangered species of Encholirium (Bromeliaceae) from Cadeia do Espinhaço, Brazil, setected using RAPD markers. Biodivers Conserv 15:4357–4373

Christenhusz MJ, Byng JW (2016) The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa 261:201–217

Collevatti RG, Rabelo SG, Vieira RF (2009) Phylogeography and disjunct distribution in Lychnophora ericoides (Asteraceae), an endangered cerrado shrub species. Ann Bot 104:655–664

Collevatti RG, Castro TG, Lima JS, Telles MPC (2012) Phylogeography of Tibouchina papyrus (Pohl) Toledo (Melastomataceae), an endangered tree species from rocky savannas, suggests bidirectional expansion due to climate cooling in the Pleistocene. Ecol Evol 2:1024–1035

Colwell RK, Brehm G, Cardelús CL, Gilman AC, Longino JT (2008) Global warming, elevational range shifts, and lowland biotic attrition in the wet tropics. Science 322:258–261

Conan Doyle A (1912) The lost world. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Conceição ADS, Queiroz LP, Lambert SM, Pereira ACS, Borba EL (2008) Biosystematics of Chamaecrista sect. Absus subsect. Baseophyllum (Leguminosae-Caesalpinioideae) based on allozyme and morphometric analyses. Plant Syst Evol 270:183–207

Cowling RM, Rundel PW, Lamont BB, Arroyo MK, Arianoutsou M (1996) Plant diversity in Mediterranean-climate regions. Trends Ecol Evol 11:362–366

Cowling RM, Potts AJ, Bradshaw PL, Colville J, Arianoutsou M, Ferrier S, Forest F, Fyllas NM, Hopper SD, Ojeda F, Procheş Ş, Smith RJ, Rundel PW, Vassilakis E, Zutta BR (2015) Variation in plant diversity in Mediterranean-climate ecosystems: the role of climatic and topographical stability. J Biogeogr 42:552–564

Crawford DJ, Archibald JK (2017) Island floras as model systems for studies of plant speciation: prospects and challenges. J Syst Evol 55:1–15

Crespi B, Nosil P (2013) Conflictual speciation: species formation via genomic conflict. Trends Ecol Evol 28:48–57

da Cruz DT, Selbach-Schnadelbach A, Lambert SM, Ribeiro PL, Borba EL (2011) Genetic and morphological variability in Cattleya elongata Barb. Rodr. (Orchidaceae), endemic to the campo rupestre vegetation in northeastern Brazil. Plant Syst Evol 294:87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-011-0444-0

da Silva RM, Fernandes GW, Lovato MB (2007) Genetic variation in two Chamaecrista species (Leguminosae), one endangered and narrowly distributed and another widespread in the Serra do Espinhaço, Brazil. Can J Bot 85:629–636

Dayrell RL, Arruda AJ, Buisson E, Silveira FAO (2016) Overcoming challenges on using native seeds for restoration of megadiverse resource-poor environments: a reply to Madsen et al. Restor Ecol 24(6):710–713

de Oliveira MM, Dickman R (2017) The advantage of being slow: the quasi-neutral contact process. PLoS One 12(8):e0182672. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182672

de Paula LF, Negreiros D, Azevedo LO, Fernandes RL, Stehmann JR, Silveira FAO (2015) Functional ecology as a missing link for conservation of a resource-limited flora in the Atlantic forest. Biodivers Conserv 24:2239–2253

de Paula LF, Forzza RC, Neri AV, Bueno ML, Porembski S (2016) Sugar Loaf Land in south-eastern Brazil: a centre of diversity for mat-forming bromeliads on inselbergs. Bot J Linn Soc 181:459–476

Duputié A, Delêtre M, De Granville JJ, McKey D (2009) Population genetics of Manihot esculenta ssp. flabellifolia gives insight into past distribution of xeric vegetation in a postulated forest refugium area in northern Amazonia. Mol Ecol 18:2897–2907

Echternacht L, Trovó M, Oliveira CT, Pirani JR (2011) Areas of endemism in the Espinhaço range in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Flora 206:782–791

Ehrlén J, van Groenendael JM (1998) The trade-off between dispersability and longevity: an important aspect of plant species diversity. Appl Veg Sci 1:29–36

Ellegren H (2014) Genome sequencing and population genomics in non-model organisms. Trends Ecol Evol 29:51–63

Feres F, Zucchi MI, de Souza AP, do Amaral MDCE, Bittrich V (2009) Phylogeographic studies of Brazilian “campo-rupestre” species: Wunderlichia mirabilis Riedel ex Baker (Asteraceae). Biotemas 22:17–26

Fernandes GW (ed) (2016) Ecology and conservation of mountaintop grasslands in Brazil. Springer, Cham

Fernandes GW, Barbosa NPU, Alberton B, Barbieri A, Dirzo R, Goulart F, Guerra TJ, Solar RRC (2018) The deadly route to collapse and the uncertain fate of Brazilian rupestrian grasslands. Biodivers Conserv 27:2587–2603

Fiedler P (2015) The fascinating ecology of two megadiverse southern hemisphere ecosystems. Conserv Biol 29:1727–1729

Fitzsimons JA, Michael DR (2017) Rocky outcrops: a hard road in the conservation of critical habitats. Biol Conserv 211:36–44

Franceschinelli EV, Jacobi CM, Drummond MG, Resende MFS (2006) The genetic diversity of two Brazilian Vellozia (Velloziaceae) with different patterns of spatial distribution and pollination biology. Ann Bot 97:585–592

Freitas L, Sazima M (2006) Pollination biology in a tropical high-altitude grassland in Brazil: interactions at the community level. Ann Mo Bot Gard 93:465–516

Gentry AH (1982) Patterns of neotropical plant species diversity. Evol Biol 15:1–84

Giannini TC, Giulietti AM, Harley RM, Viana PL, Jaffe R, Alves R et al (2017) Selecting plant species for practical restoration of degraded lands using a multiple-trait approach. Austral Ecol 42:510–521

Giulietti AM, Pirani JR (1988) Patterns of geographic distribution of some plant species from the Espinhaço Range, Minas Gerais and Bahia, Brazil. In: Heyer WR, Vanzolini PE (eds) Proceedings of a workshop on Neotropical distribution pattern. Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro, pp 39–69

Giulietti AM, Pirani JR, Harley RM (1997) Espinhaço range region. Eastern Brazil. In: Davis SD, Heywood VH, Herrera-MacBryde O, Villa-Lobos J, Hamilton AC (eds) Centres of plant diversity. A guide and strategies for the conservation, vol 3. The Americas. WWF/IUCN, Cambridge, pp 397–404

Givnish TJ, Barfuss MH, Van Ee B, Riina R, Schulte K, Horres R et al (2014) Adaptive radiation, correlated and contingent evolution, and net species diversification in Bromeliaceae. Mol Phylogenet Evol 71:55–78

Gomes V, Collevatti RG, Silveira FAO, Fernandes GW (2004) The distribution of genetic variability in Baccharis concinna (Asteraceae), an endemic, dioecious and threatened shrub of rupestrian fields of Brazil. Conserv Genet 5:157–165

Gomes VM, Negreiros D, Fernandes GW, Pires ACV, Silva ACDR, Le Stradic S (2018) Long-term monitoring of shrub species translocation in degraded Neotropical mountain grassland. Restor Ecol 26:91–96

Gomes-da-Silva J, Amorim AM, Forzza RC (2017) Distribution of the xeric clade species of Pitcairnioideae (Bromeliaceae) in South America: a perspective based on areas of endemism. J Biogeogr 44:1994–2006

Gonçalves-Oliveira RC, Wöhrmann T, Benko-Iseppon AM, Krapp F, Alves M, Wanderley MDGL, Weising K (2017) Population genetic structure of the rock outcrop species Encholirium spectabile (Bromeliaceae): the role of pollination vs. seed dispersal and evolutionary implications. Am J Bot 104:868–878

Götzenberger L, de Bello F, Bråthen KA, Davison J, Dubuis A, Guisan A et al (2012) Ecological assembly rules in plant communities—approaches, patterns and prospects. Biol Rev 87:111–127

Gradim C, Roncato J, Pedrosa-Soares AC, Cordani U, Dussin I, Alkmim FF, Queiroga G, Jacobsohn T, da Silva LC, Babinski M (2014) The hot back-arc zone of the Araçuaí orogen, Eastern Brazil: from sedimentation to granite generation. Braz J Geol 44:155–180

Greiner S, Bock R (2013) Tuning a ménage à trois: co-evolution and co-adaptation of nuclear and organellar genomes in plants. BioEssays 35:354–365

Greiner S, Rauwolf UWE, Meurer J, Herrmann RG (2011) The role of plastids in plant speciation. Mol Ecol 20:671–691

Güsewell S, Schroth MH (2017) How functional is a trait? Phosphorus mobilization through root exudates differs little between Carex species with and without specialized dauciform roots. New Phytol 215:1438–1450

Hamrick JL, Godt MJW (1990) Allozyme diversity in plant species. In: Brown AHD, Clegg MT, Kahler AL, Weir BS (eds) Plant population genetics, breeding and genetic resources. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA, pp 43–63

Hamrick JL, Godt MJW (1996) Effects of life history traits on genetic diversity in plant species. Philos Trans R Soc B 351(1345):1291–1298

Hmeljevski KV, Wolowski M, Forzza RC, Freitas L (2017a) High outcrossing rates and short-distance pollination in a species restricted to granitic inselbergs. Aust J Bot 65:315–326

Hmeljevski KV, Nazareno AG, Bueno ML, dos Reis MS, Forzza RC (2017b) Do plant populations on distinct inselbergs talk to each other? A case study of genetic connectivity of a bromeliad species in an Ocbil landscape. Ecol Evol 7:4704–4716

Hoorn C, Perrigo A, Antonelli A (2018) Mountains, climate and biodiversity: an introduction. In: Hoorn C, Perrigo A, Antonelli A (eds) Mountains, climate and biodiversity. Wiley, Chichester, pp 1–14

Hopper SD (2009) OCBIL theory: towards an integrated understanding of the evolution, ecology and conservation of biodiversity on old, climatically buffered, infertile landscapes. Plant Soil 322:49–86

Hopper SD (2018) Natural hybridization in the context of Ocbil theory. S Afr J Bot 118:284289

Hopper SD, Silveira FAO, Fiedler PL (2016) Biodiversity hotspots and Ocbil theory. Plant Soil 403:167–216

Hughes C, Eastwood R (2006) Island radiation on a continental scale: exceptional rates of plant diversification after uplift of the Andes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(27):10334–10339

Hughes CE, Pennington RT, Antonelli A (2013) Neotropical plant evolution: assembling the big picture. Bot J Linn Soc 171:1–18

Iganci JR, Heiden G, Miotto STS, Pennington RT (2011) Campos de Cima da Serra: the Brazilian subtropical highland grasslands show an unexpected level of plant endemism. Bot J Linn Soc 167:378–393

Inglis PW, Cavalcanti TB (2018) A molecular phylogeny of the genus Diplusodon (Lythraceae), endemic to the campos rupestres and cerrados of South America. Taxon 67:66–82

Jacobi CM, Carmo FF, Vincent RC, Stehmann JR (2007) Plant communities on ironstone outcrops: a diverse and endangered Brazilian ecosystem. Biodivers Conserv 16:2185–2200

Jaffé R, Prous X, Calux A, Gastauer M, Nicacio G, Zampaulo R, Souza-Filho PWM, Oliveira G, Brandi IV, Siqueira JO (2018) Conserving relics from ancient underground worlds: assessing the influence of cave and landscape features on obligate iron cave dwellers from the Eastern Amazon. PeerJ 6:e4531. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4531

Jesus FF, Solferini VN, Semir J, Prado PI (2001) Local genetic differentiation in Proteopsis argentea (Asteraceae), a perennial herb endemic in Brazil. Plant Syst Evol 226:59–68

Jesus FF, Abreu AG, Semir J, Solferini VN (2009) Low genetic diversity but local genetic differentiation in endemic Minasia (Asteraceae) species from Brazil. Plant Syst Evol 277:187–196

Khan G, Ribeiro PM, Bonatelli IA, Perez MF, Franco FF, Moraes EM (2018) Weak population structure and no genetic erosion in Pilosocereus aureispinus: a microendemic and threatened cactus species from eastern Brazil. PLoS One 13(4):e0195475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195475

Kier G, Mutke J, Dinerstein E, Ricketts TH, Küper W, Kreft H, Barthlott W (2005) Global patterns of plant diversity and floristic knowledge. J Biogeogr 32:1107–1116

Kier G, Kreft H, Lee TM, Jetz W, Ibisch PL, Nowicki C, Mutke J, Barthlott W (2009) A global assessment of endemism and species richness across island and mainland regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(23):9322–9327

Klein C (2005) Some Precambrian banded iron-formation (BIFs) from around the world: their age, geologic setting, mineralogy, metamorphism, geochemistry, and origin. Am Mineral 90:1473–1499

Krüger M, Teste FP, Laliberté E, Lambers H, Coghlan M, Zemunik G, Bunce M (2015) The rise and fall of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity during ecosystem retrogression. Mol Ecol 24:4912–4930

Lambers H, Raven JA, Shaver GR, Smith SE (2008) Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol Evol 23:95–103

Lambers H, Brundrett MC, Raven JA, Hopper SD (2010) Plant mineral nutrition in ancient landscapes: high plant species diversity on infertile soils is linked to functional diversity for nutritional strategies. Plant Soil 348:7–27

Lambers H, Albornoz F, Kotula L, Laliberté E, Ranathunge K, Teste FP, Zemunik G (2018) How belowground interactions contribute to the coexistence of mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal species in severely phosphorus-impoverished hyperdiverse ecosystems. Plant Soil 424:11–33

Lambert SM, Borba EL, Machado MC (2006a) Allozyme diversity and morphometrics of the endangered Melocactus glaucescens (Cactaceae), and investigation of the putative hybrid origin of Melocactus × albicephalus (Melocactus ernestii × M. glaucescens) in north-eastern Brazil. Plant Species Biol 21:93–108

Lambert SM, Borba EL, Machado MC, Andrade SCDS (2006b) Allozyme diversity and morphometrics of Melocactus paucispinus (Cactaceae) and evidence for hybridization with M. concinnus in the Chapada Diamantina, north-eastern Brazil. Ann Bot 97:389–403

Lanes ÉC, Pope NS, Alves R, Carvalho Filho NM, Giannini TC, Giulietti AM et al (2018) Landscape genomic conservation assessment of a narrow-endemic and a widespread morning glory from Amazonian savannas. Front Plant Sci 9(532). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00532

Lavor P, van den Berg C, Jacobi CM, Carmo FF, Versieux LM (2014) Population genetics of the endemic and endangered Vriesea minarum (Bromeliaceae) in the Iron Quadrangle, Espinhaço Range, Brazil. Am J Bot 101:1167–1175

Le Stradic S, Buisson E, Fernandes GW (2015) Vegetation composition and structure of some Neotropical mountain grasslands in Brazil. J Mt Sci 12:864–877

Le Stradic S, Fernandes GW, Buisson E (2018) No recovery of campo rupestre grasslands after gravel extraction: implications for conservation and restoration. Restor Ecol 26(S2):S151–S159

Leal BS, Chaves CJ, Koehler S, Borba EL (2016) When hybrids are not hybrids: a case study of a putative hybrid zone between Cattleya coccinea and C. brevipedunculata (Orchidaceae). Bot J Linn Soc 181:621–639

Leles B, Chaves AV, Russo P, Batista JA, Lovato MB (2015) Genetic structure is associated with phenotypic divergence in floral traits and reproductive investment in a high-altitude orchid from the Iron Quadrangle, southeastern Brazil. PLoS One 10(3):e0120645. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120645

Loeuille B, Semir J, Lohmann LG, Pirani JR (2015) A phylogenetic analysis of Lychnophorinae (Asteraceae: Vernonieae) based on molecular and morphological data. Syst Bot 40:299–315

Lousada JM, Borba EL, Ribeiro KT, Ribeiro LC, Lovato MB (2011) Genetic structure and variability of the endemic and vulnerable Vellozia gigantea (Velloziaceae) associated with the landscape in the Espinhaço Range, in southeastern Brazil: implications for conservation. Genetica 139:431–440

Lousada JM, Lovato MB, Borba EL (2013) High genetic divergence and low genetic variability in disjunct populations of the endemic Vellozia compacta (Velloziaceae) occurring in two edaphic environments of Brazilian campos rupestres. Braz J Bot 36:45–53

Madriñán S, Cortés AJ, Richardson JE (2013) Páramo is the world’s fastest evolving and coolest biodiversity hotspot. Front Genet 4(192). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00192

Main BY (1997) Granite outcrops: a collective ecosystem. J R Soc West Aust 80:113–122

Martin LJ, Blossey B, Ellis E (2012) Mapping where ecologists work: biases in the global distribution of terrestrial ecological observations. Front Ecol Environ 10:195–201

Martinelli G (1989) Campos de altitude. Editora Index, Rio de Janeiro

McCormack JE, Huang H, Knowles LL (2009) Sky islands. In: Gillespie R, Clague D (eds) Encyclopedia of islands. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA, pp 841–843

Moraes EM, Abreu AG, Andrade SC, Sene FM, Solferini VN (2005) Population genetic structure of two columnar cacti with a patchy distribution in eastern Brazil. Genetica 125:311–323

Moreira RG, McCauley RA, Cortés-Palomec AC, Fernandes GW, Oyama K (2010) Spatial genetic structure of Coccoloba cereifera (Polygonaceae), a critically endangered microendemic species of Brazilian rupestrian fields. Conserv Genet 11:1247–1255

Morellato LPC, Silveira FAO (2018) Plant life in campo rupestre: new lessons from an ancient biodiversity hotspot. Flora 238:1–10

Mucina L (2018) Vegetation of Brazilian campos rupestres on siliceous substrates and their global analogues. Flora 238:11–23

Mucina L, Wardell-Johnson GW (2011) Landscape age and soil fertility, climatic stability, and fire regime predictability: beyond the OCBIL framework. Plant Soil 341:1–23

Murphy BP, Bowman DM (2012) What controls the distribution of tropical forest and savanna? Ecol Lett 15:748–758

Negreiros D, Le Stradic S, Fernandes GW, Rennó HC (2014) CSR analysis of plant functional types in highly diverse tropical grasslands of harsh environments. Plant Ecol 215:379–388

Neves DM, Dexter KG, Pennington RT, Valente AS, Bueno ML, Eisenlohr PV et al (2017) Dissecting a biodiversity hotspot: the importance of environmentally marginal habitats in the Atlantic Forest Domain of South America. Divers Distrib 23:898–909

Neves DM, Dexter KG, Pennington RT, Bueno ML, de Miranda PL, Oliveira-Filho AT (2018) Lack of floristic identity in campos rupestres—a hyperdiverse mosaic of rocky montane savannas in South America. Flora 238:24–31

Nybom H (2004) Comparison of different nuclear DNA markers for estimating intraspecific genetic diversity in plants. Mol Ecol 13:1143–1155

Oliveira RS, Galvão HC, de Campos MC, Eller CB, Pearse SJ, Lambers H (2015) Mineral nutrition of campos rupestres plant species on contrasting nutrient-impoverished soil types. New Phytol 205:1183–1194

Overbeck GE, Vélez-Martin E, Scarano FR, Lewinsohn TM, Fonseca CR, Meyer ST, Müller SC, Ceotto P, Dadalt L, Durigan G, Ganade G, Gossner MM, Guadagnin DL, Lorenzen K, Jacobi CM, Weisser WW, Pillar VD (2015) Conservation in Brazil needs to include non-forest ecosystems. Divers Distrib 21:1455–1460

Paggi GM, Sampaio JAT, Bruxel M, Zanella CM, Goeetze M, Buettow MV, Palma-Silva C, Bered F (2010) Seed dispersal and population structure in Vriesea gigantea, a bromeliad from the Brazilian Atlantic Rainforest. Bot J Linn Soc 164:317–325

Palma-Silva C, Wendt T, Pinheiro F, Barbará T, Fay MF, Cozzolino S, Lexer C (2011) Sympatric bromeliad species (Pitcairnia spp.) facilitate tests of mechanisms involved in species cohesion and reproductive isolation in Neotropical inselbergs. Mol Ecol 20:3185–3201

Patiño J, Whittaker RJ, Borges PA, Fernández-Palacios JM, Ah-Peng C, Araújo MB et al (2017) A roadmap for island biology: 50 fundamental questions after 50 years of The Theory of Island Biogeography. J Biogeogr 44:963–983

Pereira ACS, Borba EL, Giulietti AM (2007) Genetic and morphological variability of the endangered Syngonanthus mucugensis Giul. (Eriocaulaceae) from the Chapada Diamantina, Brazil: implications for conservation and taxonomy. Bot J Linn Soc 153:401–416

Perez MF, Bonatelli IAS, Moraes EM, Carstens BC (2016a) Model-based analysis supports interglacial refugia over long-dispersal events in the diversification of two South American cactus species. Heredity 116:550–557

Perez MF, Carstens BC, Rodrigues GL, Moraes EM (2016b) Anonymous nuclear markers reveal taxonomic incongruence and long-term disjunction in a cactus species complex with continental-island distribution in South America. Mol Phylogenet Evol 95:11–19

Pianka ER (1966) Latitudinal gradients in species diversity: a review of concepts. Am Nat 100(910):33–46

Pierce S, Negreiros D, Cerabolini BE, Kattge J, Díaz S, Kleyer M et al (2017) A global method for calculating plant CSR ecological strategies applied across biomes world-wide. Funct Ecol 31:444–457

Pinheiro F, de Barros F, Palma-Silva C, Fay MF, Lexer C, Cozzolino S (2011) Phylogeography and genetic differentiation along the distributional range of the orchid Epidendrum fulgens: a Neotropical coastal species not restricted to glacial refugia. J Biogeogr 38:1923–1935

Pinheiro F, Cozzolino S, Draper D, de Barros F, Félix LP, Fay MF, Palma-Silva C (2014) Rock outcrop orchids reveal the genetic connectivity and diversity of inselbergs of northeastern Brazil. BMC Evol Biol 14:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-49

Pontara V, Bueno ML, Rezende VL, de Oliveira-Filho AT, Gastauer M, Meira-Neto JAA (2018) Evolutionary history of campo rupestre: an approach for conservation of woody plant communities. Biodivers Conserv 27:2877–2896

Poot P, Hopper SD, van Diggelen JM (2012) Exploring rock fissures: does a specialized root morphology explain endemism on granite outcrops? Ann Bot 110:291–300

Porembski S (2000) The invasibility of tropical granite outcrops (‘inselbergs’) by exotic weeds. J R Soc West Aust 83:131–134