Abstract

The statistical analysis of cross-section data very often reveals a U-shaped relationship between subjective well-being and age. This paper uses 18 waves of British panel data to try to distinguish between two potential explanations of this shape: a pure life-cycle or aging effect, and a fixed cohort effect depending on year of birth. Panel analysis controlling for fixed effects continues to produce a U-shaped relationship between well-being and age, although this U-shape is flatter for life satisfaction than for the GHQ measure of mental well-being. The pattern of the estimated cohort effects also differs between the two well-being measures and, to an extent, by demographic group. In particular, those born earlier report more positive GHQ scores, controlling for their current age; this phenomenon is especially prevalent for women.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Interest in subjective well-being across the social sciences has developed in parallel with both the greater availability of panel data, where the same individuals are followed over time, and the wider use of statistical tools to better model individual fixed effects. These statistical techniques consist of the use of panel data, or cross-section analysis with careful controls (for example, twin studies, where the initial distribution of the genetic pack of cards can be controlled for: see Bouchard et al. 1990; Kohler et al. 2005; Tellegen et al. 1988). The application of these techniques allows subjective well-being to be split up into a permanent or fixed part, and a transitory component that depends on life events. Contributions in this spirit include Lucas et al. (2003, 2004), Frijters et al. (2004), Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2004), Zimmerman and Easterlin (2006) and Blanchflower and Oswald (2008).

This interest in the effect of fixed individual characteristics has spilled over into the analysis of the relationship between well-being and age: in an econometric world plagued by accusations of endogeneity, age, sex and ethnicity typically stand out as exogenous variables, and have consequently received a great deal of attention. Early work emphasised that older individuals tended to be happier/more satisfied than younger individuals. More recent analyses have refined this approach by considering non-linear relationships between well-being and age. The results here differ somewhat between economics and psychology.

Mroczek and Kolarz (1998) find that positive affect follows an upwardly curved profile with age, while Mroczek and Spiro (2005) suggest that subjective well-being follows an inverted U-shape, peaking at around retirement age. At the same time, a vigorous literature in Economics has introduced terms in age and age-squared into well-being regressions, producing strong evidence of a U-shaped relationship which typically bottoms out somewhere between the mid-thirties and the mid-forties.Footnote 1 Curves of this type have now been identified many times in a wide variety of datasets across different countries.Footnote 2

Two popular competing interpretations of this U-shaped relationship have been proposed. One is that it reflects the passage of individuals through various stylised life events; another is that it reflects a cohort effect, so that individuals born in the 1950s, say, have (and always will have) particularly low levels of subjective well-being (hence producing a U-shape in cross-section analysis of 1990s data).Footnote 3 This paper uses two measures of well-being in 18 waves of British panel data to test the hypothesis that the age and well-being U-shape is a pure cohort phenomenon. Two types of test are presented, the first indirect, although intuitive, and the second direct. The tests are carried out on both unbalanced and balanced panel data.

The first intuitive test is based on the estimated minimum point of the U-shape. If this latter is picking up a cohort phenomenon, then the point of lowest well-being should move to the right by 1 year from data wave t to wave t + 1. The age of minimum well-being should therefore be 17 years greater in Wave 18 than in Wave 1. This turns out not to be the case. The conclusion is that there is an aging phenomenon in well-being: this is something that we will all (statistically) go through, no matter when we were born.

The second test is direct. Panel well-being regressions are estimated which control for unobserved individual fixed effects. These regressions, which hold all cohort effects constant, continue to produce U-shaped relationships between age and well-being. It is important to underline that the age effect here is obtained by examining the different levels of well-being of the same individual at different ages. Again, the conclusion is that the U-shaped relationship between age and well-being is at least partly driven by aging, rather than being a pure cohort effect.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 17.2 describes the two tests of cohort effects, and the data on which they will be carried out. Section 17.3 contains the main results regarding the persistence of the U-shaped relationship between well-being and age. Last, Sect. 17.4 concludes.

2 Cohort or Life-Cycle?

Empirical work which introduces age as one of the explanatory variables in the analysis of subjective well-being (such as life satisfaction or happiness) very often finds a U-shaped relationship, minimising somewhere in the mid-thirties to the mid-forties. As highlighted in Frey and Stutzer (2002), there is less agreement over why this U-shape so consistently results. One interpretation is that, loosely speaking, the U-shape reflects the different events that occur to individuals over the life cycle, which have a fairly systematic relationship to their age. This reading is found in Argyle (1989), Hayo and Seifert (2002) and Blanchflower and Oswald (2004). Alternatively, we might argue that, controlling for observables, well-being is broadly flat over the life-cycle, with the U-shape coming from unobserved individual heterogeneity or cohort effects.Footnote 4 In this case, with our data from the 1990s and 2000s, the hypothesis is that those in the late 1950s/late 1960s birth cohorts report lower well-being scores than do those born earlier or later.

Cross-section data does not allow us to distinguish between the life-cycle and cohort components of well-being; neither does twin data, as age and year of birth (the cohort effect) are identical across matched subjects. Progress can however be made with repeated cross-section or panel data in which we have repeated observations on individuals of the same birth cohort, over different ages, allowing the two effects to be identified separately. The increasing availability of long-run panel data has been a huge boon for the social sciences. This is particularly the case with respect to research on aging or the life-cycle.

Blanchflower and Oswald (2008) use long-run repeated cross-sectional data from the US and Europe to independently model the effect of age (in five-year blocks) and birth cohort (in 10-year blocks) on measures of subjective well-being. Heuristically, over a long enough time period, they will observe people of the same age (group) but born in different birth cohorts. This allows the separate identification of the two effects.

This paper appeals to the same kind of identification strategy, using 18 waves of British panel data to distinguish between life-cycle and cohort effects. We consider two separate tests of the hypothesis that the U-shape represents a cohort effect.

The first, indirect, test relies on the prediction of the cohort explanation that the whole U-shape should move 1 year to the right per year. In the current paper’s BHPS data, the unhappy people who were born in 1955 will be unhappy at age 36 in Wave 1 (in 1991), but equally unhappy at age 37 in Wave 2, and so on. One measure of the position of the U-shaped relationship is its minimum. The first test thus consists in seeing whether the point of minimum well-being shifts to the right by 1 year per wave.

The second, direct, test involves controlling explicitly for fixed effects in panel well-being regressions. These fixed effects will include by definition the individual’s year of birth: her cohort. Any effect of age variables in fixed-effect well-being regressions must then reflect life-cycle or aging effects: systematic changes in well-being that happen to all individuals (no matter when they were born) as they age.

2.1 Data

The data come from the first 18 waves of the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), a general survey initially covering a random sample of approximately 10,000 individuals in 5500 British households. The Wave 18 sample consists of around 15,000 individuals in 9000 households.Footnote 5 The BHPS includes a wide range of information about individual and household demographics, employment, income and health. More information on this survey is available at https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/bhps/. There is both entry into and exit from the panel, leading to unbalanced data. The BHPS is a household panel: all adults in the same household are interviewed separately. The wave 1 data were collected in late 1991 – early 1992, the wave 2 data were collected in late 1992 – early 1993, and so on. The analysis in this paper refers to individuals aged between 16 and 64, and will be carried out on both unbalanced and balanced panel data.

The central question addressed here is whether individual well-being changes systematically over the life cycle.Footnote 6 Two measures of subjective well-being are considered: the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), which appears in all waves of the BHPS, and overall life satisfaction, which appears in Waves 6–10, and then 12–18. There are 2161 individuals who provided a GHQ score at every wave of the BHPS, so that the balanced panel analysis can be carried out on a maximum of 38,898 observations. Equally, 3063 individuals provided 12 separate life-satisfaction scores, for a maximum balanced sample consisting of 36,756 life satisfaction observations. In practice, the balanced regression analysis uses slightly fewer observations due to missing values for some of the explanatory variables.

The GHQ-12 (see Goldberg 1972) reflects overall mental well-being. It is constructed from the responses to 12 questions (administered via a self-completion questionnaire) covering feelings of strain, depression, inability to cope, anxiety-based insomnia, and lack of confidence, amongst others (the 12 questions are reproduced in Appendix A). Responses are made on a four-point scale of frequency of a feeling in relation to a person’s usual state: “Not at all”, “No more than usual”, “Rather more than usual”, and “Much more than usual”.Footnote 7 The GHQ is widely used in medical, psychological and sociological research, and is considered to be a robust indicator of the individual’s psychological state. The between-item validity of the GHQ-12 is high in this sample of the BHPS, with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.90.

This paper uses the Caseness GHQ score, which counts the number of questions for which the response is in one of the two ‘low well-being’ categories. This count is then reversed so that higher scores indicate higher levels of well-being, running from 0 (all 12 responses indicating poor psychological health) to 12 (no responses indicating poor psychological health).Footnote 8 The distribution of this well-being index in the BHPS sample is shown in the first panel of Appendix B (Table 17.4). The median and mode of this distribution is 12: no responses indicating poor psychological health. There is however a long tail: one-third of the sample have a score of 10 or less, and 13% have a score of 6 or less.

The second measure is satisfaction with life, which appears in Waves 6–10 and 12–18 of the BHPS. Respondents are asked “How dissatisfied or satisfied are you with your life overall”, with responses measured on a scale of one (not satisfied at all) to seven (completely satisfied). The distribution of replies is shown in the second panel of Appendix B (Table 17.5). The median score is five, with a mode of six and a mean of 5.2.

The following section considers how both of these well-being measures are related to age, both with and without controls for cohort effects.

3 Well-Being and Age: Pooled and Panel Results

3.1 Well-Being and Age in Pooled Data

Table 17.1 sets the scene by presenting the results from what are by now fairly ‘standard’ well-being equations, here estimated on pooled data. All of the regressions in this paper are estimated using linear techniques. The pooled analysis in Table 17.1 comes from OLS estimation; the panel results below come from ‘within’ regressions. It can, of course, be objected that the assumption of cardinality required for OLS is unlikely for well-being measures (is someone with a life satisfaction score of six exactly twice as happy as someone with a life satisfaction score of three?). However, Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) have shown that, practically, the difference between the ordinal and cardinal estimation of subjective well-being is small compared to the difference between pooled and panel results. More pragmatically, all of the results presented in this paper can be reproduced using appropriate ordinal estimation methods (ordered probit for the pooled analysis, and conditional fixed effect logits for the panel regressions).

Column 1 of Table 17.1 shows the results from pooled cross-section regressions of GHQ scores, while column 2 carries out the same analysis for life satisfaction. The regressions include age and age-squared as explanatory variables, as well as a standard set of controls (for the log of monthly income, sex, education, labour-force status, marital status, number of children, renter, and wave and region dummies). The very significant coefficients on age (negative) and age-squared (positive) reveal that, ceteris paribus, well-being is U-shaped in age. Some simple algebra shows that the age of minimum well-being is 39 for GHQ and 42 for life satisfaction.

The estimated coefficients on the other right-hand side variables are all by now common in the empirical well-being literature. Unemployment, marital status and health have large impacts on both measures of well-being in the expected direction. There are, however, three notable variables that have opposing effects on GHQ and life satisfaction. Both incomeFootnote 9 and self-employment are associated with higher life-satisfaction scores, but also greater mental stress. On the contrary, men report lower life-satisfaction scores, but also less mental stress.Footnote 10 One last point to note in the context of well-being and age is that it is contentious to include health as a right-hand side variable,Footnote 11 although this practice is widespread in the literature. Including health does imply that we are comparing individuals of different (working) ages, but with the same level of health. We will return to this issue below.

3.2 Test 1: Does the U-Shape Move to the Right by One Year Per Survey Wave?

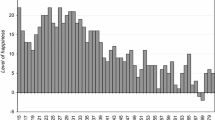

If the U-shape in age is a pure cohort phenomenon, then the age distribution of well-being should shift to the right by 1 year per wave. This hypothesis can be tested by re-running Table 17.1’s regressions separately for each of the 18 waves of the BHPS, and calculating the estimated age of minimumFootnote 12 well-being in each wave. The results are summarised in Fig. 17.1. Under the pure cohort hypothesis, the estimated age of minimum well-being would increase by 1 year per wave, tracing out a 45-degree line. Figure 17.1 shows little evidence of this for either of our well-being measures. Although the estimated minimum of GHQ does rise a little at the very beginning of the sample period, there is no strong trend thereafter.

The BHPS is an unbalanced panel. It is therefore theoretically possible that the pattern of well-being amongst those who enter and exit the data distorts the true relationship between well-being and age. To investigate, the bottom panel of Fig. 17.1 repeats the analysis using balanced panel data (over all 18 waves for the GHQ, and over 12 waves for life satisfaction). The balanced results again provide little support for the hypothesis that the age distribution shifts to the right by 1 year per wave.Footnote 13

There is of course quite severe selection in the bottom panel, as we require individuals to be present in all waves for which subjective well-being is measured. As a halfway house, we can look at the balanced results using only the last 10 years of the BHPS (i.e. waves 9 through 18). This more than doubles the number of individuals in the balanced GHQ analysis (from 2161 to 4727) and increases the number in the life-satisfaction analysis by just over a half (3063 to 4828). The results continue to show only weak evidence of a U-shape that shifts to the right by 10 year per year. The age of minimum GHQ figures does rise from Waves 9–18 here, but only in the last two waves, while the rise in the age of minimum life satisfaction is of 3 years over the 10-year period, again concentrated in the last two waves.

This evidence then points to at least some role for a pure life-cycle effect, whereby well-being for the same individual evolves systematically with age. It should be borne in mind, however, that the age of minimum well-being, which is the ratio of two estimated coefficients, is likely measured with a certain degree of error; as such we cannot consider Test 1’s results to be definitive, but rather suggestive. What follows is a direct test of the importance of cohort effects that escapes this criticism.

3.3 Test 2: Introducing Individual Fixed Effects

A perhaps simpler approach to the question is to introduce controls for unobserved heterogeneity, i.e. individual fixed effects. To allow for a flexible relationship between well-being and age, ten age dummies are created. The first refers to age 16–19, then 20–24, 25–29 and so on up to 60–64. The youngest age group is the omitted category, so all of the estimated coefficients in Table 17.2 are to be read as relative to the well-being of the youngest.

This approach is simple, but does fall foul of the Age-Period-Cohort problem. Individuals who are born in year C (this is their cohort) and are currently A years old are interviewed in year P. The issue is that C, A and P are (almost) multicollinear. For example, a 50 year-old BHPS respondent interviewed in 2008 must have been born in either 1957 or 1958. We can only identify age, period and cohort effects separately by (i) Using information on birthdays (as in the example above), and imagining a discrete jump in subjective well-being on the day of the birthday, (ii) Parameterising one of the relationships (for example, imposing a quadratic in age), or (iii) Converting one of the variables into multi-year blocks.

An attractive alternative is to not estimate the cohort effects at all, but rather difference them out. Here the first-difference change in life satisfaction is estimated as a function of age. A first contribution here is Van Landeghem (2012), who shows that this first difference rises somewhat up to age 55 in SOEP data, so that the age to well-being relationship is convex. More recently, Cheng et al. (2017) show that this first difference is positive in four datasets (BHPS, HILDA, SOEP and MABEL), and that it starts negative and then turns positive at around age 30, which is what a U-shaped relationship would predict.

Table 17.2 takes the third approach above, and shows three sets of regression results for both GHQ and life satisfaction.Footnote 14 The first two regressions are estimated on pooled data. The first of these includes only the age dummies on the right-hand side, and thus provides a non-parametric unconditional estimate of the relationship between well-being and age. Well-being is U-shaped, with minimum well-being occurring at age 40–44 for both measures. The second column then introduces the other demographic controls used in Table 17.1. These controls make the U-shape more pronounced, if anything,Footnote 15 and do not change the age of minimum well-being.

The last column introduces individual fixed effects. The estimated coefficients on the age dummies in column 3 therefore represent the different levels of well-being reported by the same individual as they go through the life cycle. Of course, even with fairly long-run panel data, we do not observe the complete sequence of ages for any respondent. In the BHPS, any one individual can appear in a maximum of five different age categories in the GHQ regressions (over 18 waves) and four different age categories in the life-satisfaction regressions (between waves 6 and 18).

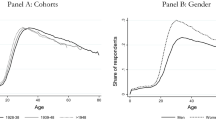

The main result from this panel analysis is that, even controlling for individual fixed effects, well-being continues to show a U-shaped relationship with age. This is true for both GHQ and life satisfaction, although the U-shape is more pronounced for the former than for the latter. The age of minimum well-being, controlling for fixed effects, is in the forties for both measures. The estimated relationships between well-being and age in pooled and panel data are illustrated in Fig. 17.2. It is notable that the left-hand side of the ‘U’ in the life-satisfaction regressions with individual fixed effects depends entirely on the drop in well-being between ages 16–19 and 20–24. Thereafter, life satisfaction stays fairly flat up until the end of the forties.

As with Test 1, which looked at the estimated age of minimum well-being by wave, it is important to take panel exit and entry into account. Table 17.3 therefore repeats the analysis described in Table 17.2, but now estimated only on the balanced sample (a little over 2000 individuals for the GHQ score, and just over 3000 for life satisfaction). Even in this much smaller balanced sample, the top panel of Table 17.3 shows a persistent U-shaped relationship between age and GHQ. In the bottom panel, the relationship between age and life satisfaction is now less evident. Even so, the U-shape persists in the estimated coefficients, which are jointly significant. In addition, the real test of the U-shape is whether the ends are greater than the middle, loosely speaking. This test passes at around the 1% level comparing both the oldest and the youngest age-groups to those in their mid-forties.

3.4 Interpreting the Results

Well-being continues to be U-shaped in age even after cohort effects (via individual fixed effects) have been controlled for. As such, the well-being of any one individual, no matter when they were born, will trace out the profile given by the ‘panel’ lines in Fig. 17.2 as they age. While it is easy to think of some aspects of life which might systematically be more difficult between the ages of 35 and 45, it is worth emphasising that the multivariate analyses controls for a number of these (labour-force and marital status, home ownership, and number of children). One open question is therefore what lies behind the life cycle events that hit hard between the ages of 35 and 45. One possibility might be stress at work (perhaps combined with young or adolescent children), although useful questions measuring such phenomena are not always present in large-scale datasets.

As a by-product of the regression in column 3 of Table 17.2, we can look at the distribution of the estimated fixed effects by birth cohort. Specifically, we calculate the average value of the individual fixed effects by year of birth: these are presented graphically in Appendix C (Figs. 17.3 and 17.4). A small number of birth years for which there were fewer than 20 individuals in the cell have been dropped: this applies particularly to the graphs by level of education. The shape of the cohort effects presented in Appendix C can actually be inferred from Fig. 17.2. In the latter, both of the pooled and panel results GHQ curves are U-shaped, and the distance between the two curves is greater for the older age-groups than for the younger age-groups: in other words, those born earlier report higher levels of well-being on the GHQ scale, independent of their current age.Footnote 16 This is indeed what we see in the top left panel of Appendix C: those born earlier have higher levels of SWB (which is what Blanchflower and Oswald, 2004, concluded from their analysis of US General Social Survey data as well). Even so, the size of this estimated cohort effect is not overwhelmingly large: the difference in the cohort effects between those born in the 1930s and those born in the 1970s is about one-eighth of a GHQ point, on the 0–12 scale. By way of comparison, this is the size of the estimated effect of divorce on well-being in the pooled cross-section estimates in Table 17.1, but only about one-third of the size of the effect of separation or unemployment.

The same visual test for the life-satisfaction curves in Fig. 17.2 suggests that the fixed effects are U-shaped. The pooled results are markedly U-shaped, but the panel results are less so. The difference between them is the fixed effect, which must therefore itself have a U-shaped distribution. In this case, it does seem to be true that those born around the late 1950s to early 1960s have (fixed) lower levels of life satisfaction. Again, this is what we see in Appendix C.Footnote 17

Why do the fixed effects have this pattern? Any attempt at explanation will be speculative, as by definition fixed effects reflect unobserved differences between individuals. With respect to the GHQ, one such piece of speculation as to why those born earlier have, ceteris paribus, higher levels of mental well-being appeals to social comparisons. Researchers in a number of social-science disciplines have emphasised the importance of comparisons to reference groups (Adams 1965; Frank 1989; Kapteyn et al. 1978; Pollis 1968). One likely type of comparison here is with respect to the past, and perhaps even to a certain defined period (the parents’ situation during the individuals’ childhood, or the individual’s first job, for example). Secularly-rising living standards will then imply that older cohorts compare current outcomes to less well-off reference groups, and will consequently report higher well-being scores.Footnote 18 Alternatively, Rodgers (1982) posits that older cohorts might be happier as a result of having survived economic deprivation and other social hardships, whereas younger cohorts could have higher levels of needs once basic survival issues have been resolved. Last, comparisons can themselves change within individual over time, and help to explain the U-shape in age itself (as in Schwandt 2016).

3.5 What Should We Control For?

As mentioned above, there are a number of different ways of looking at the relationship between age and well-being. An analysis without any control variables, as in column 1 of Tables 17.2 and 17.3, produces a description of well-being at different ages, without taking into account the sex, income, housing etc. composition of different age groups. The analyses in the other columns of Tables 17.2 and 17.3 do include some standard right-hand side control variables, so that we are to an extent comparing like with like. There does remain, however, the question of how sensible the latter comparisons are. In particular, some of the control variables (income, marriage, labour-force status) might be thought to be partly determined by well-being. To check whether reverse causality is behind the findings above, all of the regressions have been re-run retaining only exogenous explanatory variables (sex, wave and region). The qualitative results remained unchanged.

3.6 Is Everyone the Same?

It is of interest to carry out the above analysis separately for different demographic groups. Specifically, Table 17.2’s regressions were re-run for men and for women, and for three different educational groups (where high education corresponds to qualifications obtained in higher education, and medium education to A-Level, O-Level or Nursing qualifications). The estimated cohort effects are shown in Appendix C.

Both the estimated U-shape and the fixed effects profiles differ by demographic group. The U-shaped relationship between well-being and age is much more pronounced for men than for women. In addition, the negative trend in the GHQ fixed effect (so that older cohorts are happier than younger cohorts) is found only for women. Note that this cannot reflect patterns of employment or number of children, as these variables are controlled in the regression. The profile is however consistent with changing work intensity for women, or increasing difficulty in ensuring an adequate work-life balance. Regarding education, the U-shape is stronger for the higher-educated than for the other groups, and the negative trend in the GHQ fixed effect is found only for the higher-educated. However, the U-shaped fixed effect in life satisfaction is found for all demographic groups.

4 Conclusion

This paper has used 18 waves of British panel data to confirm that subjective well-being is U-shaped in age in pooled data. The application of panel-analysis techniques allows us to distinguish the life-cycle or ageing component of this relationship from the fixed effect or cohort part. The results show that, even controlling for individual fixed effects, both life satisfaction and GHQ scores remain U-shaped in age. The analysis of the fixed effect in GHQ scores reveals that individuals from earlier cohorts (i.e. those who were born earlier) have, ceteris paribus, distinctly higher levels of subjective well-being, as measured by the GHQ-12 score, than those from later cohorts. This pattern is markedly different by sex, and by level of education. The fixed effects in life satisfaction exhibit a U-shaped relationship.

The main result of this analysis may be considered as essentially negative: whereas we previously thought that there was only one phenomenon to explain (the U-shape), there would now appear to be two: a U-shaped life-cycle or aging effect, and the cohort profiles. This paper has not explicitly tested any theories of why these data shapes pertain, although the GHQ fixed-effects results are consistent with reference group theory, in that those born earlier may have lower standards of comparison, and with increasing work-life balance stress.

This paper’s conclusions are based on British data, although the robust U-shaped relationship is found across two rather different measures of well-being (while weaker for life satisfaction than for the GHQ). It may be that other datasets will produce different results. The simple method used in this paper can be easily applied to any panel data set of sufficiently long duration. The empirical well-being literature should perhaps now pay more attention to the structure of the fixed effect, and in particular to its relationship with year of birth.

Notes

- 1.

The sample in Mroczek and Spiro (2005) actually consists of veterans over the age of 40, so that their finding of an upward-sloping profile is not inconsistent with a U-shape over all ages.

- 2.

Graham and Ruiz Pozuelo (2017) find a U-shape in 44 out of 46 countries investigated in Gallup World Poll data. This conclusion does not however hold for all well-being measures. In Stone et al. (2010), a U-shape is found for the Cantril ladder and positive emotions in Gallup data, but not for negative emotions.

- 3.

Putnam (2000), page 141, concludes that the decline in trust in the US is purely a cohort phenomenon, with each cohort’s trust not changing over time.

- 4.

This is the conclusion reached by Easterlin and Schaeffer (1999), using 20 years of cohort data from the US General Social Survey. Kassenböhmer and Haisken-DeNew (2012) suggest that the U-shape in German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) data is entirely explained by individual fixed effects and experience in the panel. Cribier (2005) is an evocative account of the differences in life experience between two cohorts of French workers born only 14 years apart.

- 5.

The wave 1 sample was drawn from 250 areas of Great Britain. Additional samples of 1500 households in each of Scotland and Wales were added to the main sample in 1999, and in 2001 a sample of 2000 households was added in Northern Ireland.

- 6.

More precisely: whether subjective well-being changes systematically in a way that cannot be explained by the standard set of explanatory variables (covering income, employment, health, demographics etc.).

- 7.

One worry is that the GHQ is singularly unsuitable for this kind of analysis, as its constituent parts are explicitly phrased in terms of comparisons to usual. It is worth noting that the empirical literature on GHQ scores treats them unambiguously as indicators of the level of well-being, and it was for this purpose that the instrument was designed. On a practical level, the employed’s GHQ is more strongly correlated with job satisfaction levels in the BHPS data than with job satisfaction changes. Last, with 18 years of balanced panel data, a relatively direct test of the usefulness of the GHQ score in this respect can be envisaged. If events become more ‘usual’ as an individual ages, then the standard deviation of GHQ scores (and of its individual components) will fall with age. There is no evidence of this phenomenon in balanced BHPS panel data.

- 8.

Alternatively, the responses to the GHQ-12 questions can be used to construct what is known as a Likert measure. This is the simple sum of the responses to the 12 questions, coded so that the response with the lowest well-being value scores 3 and that with the highest well-being value scores 0. This count is then reversed, so that higher scores indicate higher levels of well-being. The measure thus runs from 0 (all 12 responses indicating the worst psychological health) to 36 (all responses indicating the best psychological health). Practically, the results are very similar between the Caseness and Likert measures.

- 9.

Income is measured in real terms, having been deflated by the CPI.

- 10.

Nolen-Hoeksema and Rusting (1999) conclude in their survey article that women exhibit higher incidence rates for almost all of the mood and anxiety disorders, but in general report higher levels of happiness.

- 11.

Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) explicitly do not control for health in their statistical analysis.

- 12.

Alternatively, interaction terms between age and wave can be introduced into Table 1’s regressions; these give qualitatively very similar results.

- 13.

Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) carry out a similar test on American General Social Survey data, and conclude that there is only slight evidence that the minimum moves to the right over time. The GSS is not, however, a panel.

- 14.

This is also the approach is taken in Blanchflower and Oswald (2008), where the cohort appears in 10-year blocks. Wunder et al. (2013) do not introduce cohort effects at all, and estimate the age profile semi-parametrically in BHPS and SOEP data, which produces a U-shape (deeper in the BHPS) up until the age of retirement.

- 15.

It has often been observed that income is hump-shaped in age, for example, so that holding income constant will deepen the well-being U-shape. Equally, Glaeser et al. (2002) suggest that social capital is hump-shaped in age. Frijters and Beatton (2012) find that introducing controls deepens the U-shape in their analysis of SOEP, Australian HILDA and BHPS panel data.

- 16.

Easterlin (2006) reaches a similar conclusion for happiness in US cohorts.

- 17.

Blanchflower and Oswald (2008) also find a U-shaped pattern of birth cohort effects in life satisfaction, using 27 years of Eurobarometer data.

- 18.

Such comparisons to the past imply that, in the long run, the correlation between GDP per capita and individual well-being may well be small. For some recent empirical contributions to this debate, see Diener and Oishi (2000), Easterlin (1995) and Oswald (1997). This literature is surveyed in Clark et al. (2008).

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2). New York/London: Academic.

Argyle, M. (1989). The psychology of happiness. London: Routledge.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is wellbeing U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1733–1749.

Bouchard, T. J., Lykken, D. T., McGue, M., Segal, N. L., & Tellegen, A. (1990). Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota Study of twins reared apart. Science, 250, 223–228.

Cheng, T., Oswald, A. J., & Powdthavee, N. (2017). Longitudinal evidence for a midlife nadir in human well-being: Results from four data sets. Economic Journal, 127, 126–142.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. (2008). Relative income, happiness and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46, 95–144.

Cribier, F. (2005). Changes in the experience of life between two cohorts of Parisian pensioners, born in circa 1907 and 1921. Aging & Society, 25, 1–18.

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Cross-cultural psychology of subjective well-being. Boston: MIT Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27, 35–47.

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 463–482.

Easterlin, R. A., & Schaeffer, C. M. (1999). Income and subjective well-being over the life-cycle. In C. D. Ryff & V. W. Marshall (Eds.), The self and society in aging processes. New York: Springer.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frank, R. H. (1989). Frames of reference and the quality of life. American Economic Review, 79, 80–85.

Frey, B. S. & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Frijters, P., & Beatton, T. (2012). The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82, 525–542.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J., & Shields, M. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real incomes and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94, 730–740.

Glaeser, E., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital. Economic Journal, 112, 437–458.

Goldberg, D. P. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graham, C., & Ruiz Pozuelo, J. (2017). Happiness, stress, and age: How the U curve varies across people and places. Journal of Population Economics, 30, 225–264.

Hayo, B., & Seifert, W. (2002). Subjective economic well-being in Eastern Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 24, 329–348.

Kapteyn, A., van Praag, B. M. S., & van Herwaarden, F. G. (1978). Individual welfare functions and social reference spaces. Economics Letters, 1, 173–177.

Kassenböhmer, S. C., & Haisken-DeNew, J. (2012). Heresy or enlightenment? The well-being age U-shape effect is flat. Economics Letters, 117, 235–238.

Kohler, H.-P., Behrman, J., & Skytthe, A. (2005). Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review, 31, 407–445.

Lucas, R., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2003). Re-examining adaptation and the setpoint model of happiness: Reaction to changes in marital status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 527–539.

Lucas, R., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2004). Unemployment alters the set-point for life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 15, 8–13.

Mroczek, D. K., & Kolarz, C. M. (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1333–1349.

Mroczek, D. K., & Spiro, A. (2005). Change in life satisfaction during adulthood: Findings from the veterans affairs normative aging study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 189–202.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Rusting, C. L. (1999). Gender differences in well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Oswald, A. J. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. Economic Journal, 107, 1815–1831.

Pollis, N. P. (1968). Reference group re-examined. British Journal of Sociology, 19, 300–307.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rodgers, W. (1982). Trends in reported happiness within demographically defined subgroups, 1957–78. Social Forces, 60, 826–842.

Schwandt, H. (2016). Unmet aspirations as an explanation for the age U-shape in wellbeing. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 122, 75–87.

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(22), 9985–9990.

Tellegen, A., Lykken, D. T., Bouchard, T. J., Wilcox, K. J., Segal, N. L., & Rich, S. (1988). Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1031–1039.

Van Landeghem, B. (2012). A test for the convexity of human well-being over the life cycle: Longitudinal evidence from a 20-year panel. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81, 571–582.

Van Praag, B., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2004). Happiness quantified. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wunder, C., Wiencierz, A., Schwarze, J., & Küchenhoff, H. (2013). Well-being over the life span: Semiparametric evidence from British and German longitudinal data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 154–167.

Zimmerman, A., & Easterlin, R. (2006). Happily ever after? Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and happiness in Germany. Population and Development Review, 32, 511–528.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dick Easterlin, Carol Graham, David Halpern, Mike Hagerty, Laurence Hazelrigg, Felicia Huppert, Hendrik Juerges, Nicolai Kristensen, Ken Land, Orsolya Lelkes, Andrew Oswald, Steve Platt, Claudia Senik, Andrew Sharpe, Peter Warr and Rainer Winkelmann for useful discussions. The BHPS data were made available through the ESRC Data Archive. The data were originally collected by the ESRC Research Centre on Micro-social Change at the University of Essex. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A

The 12 questions used to create the GHQ-12 measure appear in the BHPS questionnaire as follows:

-

1.

Here are some questions regarding the way you have been feeling over the last few weeks. For each question please ring the number next to the answer that best suits the way you have felt.

Have you recently… .

-

a)

been able to concentrate on whatever you’re doing?

Better than usual 1

Same as usual 2

Less than usual 3

Much less than usual 4

then

-

b)

lost much sleep over worry?

-

e)

felt constantly under strain?

-

f)

felt you couldn’t overcome your difficulties?

-

i)

been feeling unhappy or depressed?

-

j)

been losing confidence in yourself?

-

k)

been thinking of yourself as a worthless person?

with the responses:

Not at all 1

No more than usual 2

Rather more than usual 3

Much more than usual 4

then

-

c)

felt that you were playing a useful part in things?

-

d)

felt capable of making decisions about things?

-

g)

been able to enjoy your normal day-to-day activities?

-

h)

been able to face up to problems?

-

i)

been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered?

with the responses:

More so than usual 1

About same as usual 2

Less so than usual 3

Much less than usual 4

-

a)

1.2 Appendix B

1.3 Appendix C

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Clark, A.E. (2019). Born to Be Mild? Cohort Effects Don’t (Fully) Explain Why Well-Being Is U-Shaped in Age. In: Rojas, M. (eds) The Economics of Happiness. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-15834-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-15835-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)