Abstract

Game Analytics has gained a tremendous amount of attention in game development and game research in recent years. The widespread adoption of data-driven business intelligence practices at operational, tactical and strategic levels in the game industry, combined with the integration of quantitative measures in user-oriented game research, has caused a paradigm shift. Historically, game development has not been data-driven, but this is changing as the benefits of adopting and adapting analytics to inform decision making across all levels of the industry are becoming generally known and accepted.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Changing the Game

Game Analytics has gained a tremendous amount of attention in game development and game research in recent years. The widespread adoption of data-driven business intelligence practices at operational, tactical and strategic levels in the game industry, combined with the integration of quantitative measures in user-oriented game research, has caused a paradigm shift. Historically, game development has not been data-driven, but this is changing as the benefits of adopting and adapting analytics to inform decision making across all levels of the industry are becoming generally known and accepted.

While analytics practices play a role across all aspects of a company, the introduction of analytics in game development has, to a significant extent, been driven by the need to gain better knowledge about the users – the players. This need has been emphasized with the rapid emergence of social online games and the Free-to-Play business model which, heavily inspired by web- and mobile analytics, relies on analysis of comprehensive user behavior data to drive revenue. Outside of the online game sector, users have become steadily more deeply integrated into the development process thanks to widespread adoption of user research methods. Where testing used to be all about browbeating friends and colleagues into finding bugs, user testing and research today relies on sophisticated methods to provide feedback directly on the design.

Operating in the background of these effects is the steady increase in the size of the target audience for games, as well as its increasing diversification. This has brought an opportunity for the industry to innovate on different forms of play allowing different types of interactions and contexts, and the accommodation of different types of users of all ages, intellectual abilities, and motivations. Now, more than ever, it is necessary for designers to develop an understanding of the users and the experiences they obtain from interacting with games. This has marked the birth of Games User Research (GUR) – a still emerging field but an important area of investment and development for the game industry, and one of the primary drivers in establishing analytics as a key resource in game development.

Game analytics is, thus, becoming an increasingly important area of business intelligence for the industry. Quantitative data obtained via telemetry, market reports, QA systems, benchmark tests, and numerous other sources all feed into business intelligence management, informing decision-making. Measures of processes, performance and not the least user behaviors collected and analyzed over the complete life cycle of a game – from cradle to grave – provides stakeholders with detailed information on every aspect of their business. From detailed feedback on design, snapshots of player experience, production performance and the state of the market. Focusing on user-focused analytics, there are multiple uses in the development pipeline, including the tracking and elimination of software bugs, user preferences, design issues, behavior anomalies, and monetization data, to mention a few.

2 About This Book

This book is about game analytics. It is meant for anybody to pick up – novice or expert, professional or researcher. The book has content for everyone interested in game analytics.

The book covers a wide range of topics under the game analytics umbrella, but has a running focus on the users. Not only is ‘user-oriented analytics’ one of the main drivers in the development of game analytics, but users are, after all, the people games are made for. Additionally, the contributions in this book – written by experts in their respective domains – focus on telemetry as a data source for analytics. While not the only source of game business intelligence, telemetry is one of the most important ones when it comes to user-oriented analytics, and has in the past decade brought unprecedented power to Game User Research.

The book is composed of chapters authored by professionals in the industry as well as researchers, and in several cases in collaboration. These are augmented with a string of interviews with industry experts and top researchers in game analytics. This brings together the strengths of both worlds (the industry and academic) and provides a book with a broad selection of in-depth examples of the application of user-oriented game analytics. It also means the book presents a coherent picture of how game analytics can be used to analyze user behavior in the service of stakeholders in both the industry and academia, including: designers who want to know how to change games for building ultimate experiences and boosting retention, business VPs hoping to increase their product sales, psychologists interested in understanding human behavior, computer scientists working on data mining of complex datasets, learning scientists who are interested in developing games that are effective learning tools, game user research methodologists who are interested in developing valid methods to tackle the question of game user experience measurement and evaluation.

Chapters in this book provide a wealth of experiences and knowledge; the urging purpose behind the book is to share knowledge and experiences of the pros and cons of various techniques and strategies in game analytics – including different collection, analysis, visualization and reporting techniques – the building blocks of game analytics systems. In addition, the book also serves to inform practitioners and researchers of the variety of uses and the value of analytics across the game lifecycle, and about the current open problems. It is our ultimate goal to stimulate the existing relations between industry and research, and take the first step towards building a methodological and theoretical foundation for game analytics.

3 Game Analytics, Metrics and Telemetry: What Are They?

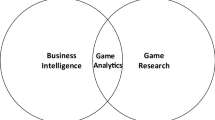

In this book you will see the following words often repeated: game metrics, game telemetry and game analytics. These terms are today often used interchangeably, primarily due the relative recent adoption of the terms analytics, telemetry and metrics in game development. To clear away any confusion, let us quickly define them. Game analytics is the application of analytics to game development and research. The goal of game analytics is to support decision making, at operational, tactical and strategic levels and within all levels of an organization – design, art, programming, marketing, user research, etc. Game analytics forms a key source of business intelligence in game development, and considers both games as products, and the business of developing and maintaining these products. In recent years, many game companies – from indie to AAA – have started to collect game telemetry. Telemetry is data obtained over a distance. This can, for example, be quantitative data about how a user plays a game, tracked from the game client and transmitted to a collection server. Game metrics are interpretable measures of something related to games. More specifically, they are quantitative measures of attributes of objects. A common source of game metrics is telemetry data of player behavior. This raw data can be transformed into metrics, such as “total playtime” or “daily active users” – i.e. measures that describe an attribute or property of the players. Metrics are more than just measures of player behavior, however; the term covers any source of business intelligence that operates in the context of games. Chapter 2 delves deeper to outline the definitions of the terms and concepts used within the different chapters in the book.

4 User-Oriented Game Analytics

The game industry is inherently diverse. Companies have established their own processes for game analytics, which tend to be both similar and different across companies, depending on the chosen business model, core design features and the intended target audience.

To start with the sector of the industry that relies directly and heavily on user-oriented analytics, social online game companies produce games that are played within a social context, either synchronously or asynchronously between a small or large number of players over a server. Many games supporting large-scale multi-player interaction feature a persistent world that users interact within. For these types of games, and social online games in general, companies can release patches at any time and most of the time they add or adjust the game during the lifecycle of the product. Due to this flexibility, companies that produce these types of games usually release the product early and then utilize massive amounts of game telemetry analysis to adjust the game and release new content based on what players are doing. Companies that produce these types of games include Zynga Inc. and Blizzard Entertainment, to mention a few. Chapter 4 delves a bit deeper on the process involved in creating these types of games.

In addition to social game companies, the traditional one-shot retail game model comprises the majority of the industry, today. In this category we find the big franchises like Assassin’s Creed (Ubisoft), Tomb Raider (Square Enix) and NBA (Electronic Arts). Most of the time these games do not feature persistent worlds, and thus do not have the same degree of opportunity to adjust products after launch on a running basis, although this may be changing due to the presence of online distribution networks like Valve’s Steam. However, during production, user-oriented analytics can be used for a large variety of purposes, not the least to help user research departments assist designers in between iterations. This book includes multiple examples of this kind of analytics work, including Eric Hazan’s chapter (Chap. 21) describing the methodologies used at Ubisoft to measure the user experience, Drachen et al. (Chap. 14) describing user research at Crystal Dynamics and IO Interactive, and Jordan Lynn’s chapter (Chap. 22) describing the methods of value to Volition, Inc. Another interesting example of the use of analytics within the production cycle at Bioware is discussed at length by Georg Zoeller (Chap. 7). Sree Santhosh and Mark Vaden describe their work at Sony Online Entertainment (Chap. 6) and Tim Fields provides an overview of metrics for social online games (Chap. 4).

Of course, recently there has been a mix of AAA titles that also have social or casual components played online. These include Electronic Arts (EA) Sport’s FIFA game, which includes an online component with a persistent world. For these games, a mix of approaches and processes are applicable.

5 User-Oriented Game Research

As discussed above, Game User Research is a field that studies user behavior. The field is dependent on the methodologies that have been developed in academia, such as quantitative and qualitative methods used within human-computer interaction, social science, psychology, communications and media studies. Digital games present an interesting challenge as they are interactive, computational systems, where engagement is an important factor. For such systems, academics within the user research area have been working hard to adopt and extend the methodologies from other fields to develop appropriate tools for games.

Looking at game analytics specifically, industry professionals and researchers have collaborated to push the frontier for game analytics and analytics tools. Some of this work is covered in Drachen et al.’s work on spatial analysis (Chap. 17) and game data mining (Chap. 12), showing examples of analysis work in games developed and published by Square Enix studios. Also, Medler’s work with Electronic Arts (Chap. 18) where he explored the use of different visualization techniques to serve different stakeholders, and Seif El-Nasr et al.’s work with Pixel Ante and Electronic Arts (Chap. 19) where they explored the development of novel visual analytics systems that allow designers to make sense of spatial and temporal behavioral data.

Researchers in the game user research area have been pushing the frontier of methods and techniques in several directions. Some researchers have started to explore triangulation of data from several sources, including metrics and analytics with other qualitative techniques. Examples of these innovative methodologies can be seen in this book. For example, Sundstedt et al.’s chapter (Chap. 25) discusses eye tracking metrics as a behavioral data source, and McAllister et al.’s chapter (Chap. 27), which follows Nacke’s chapter (Chap. 26) introduction to physiological measures with a presentation of a novel method triangulating game telemetry with physiological measures.

In addition to innovation in tools and techniques that can be used in industry and research, experts in social sciences, communication, and media studies have also been exploring the use of analytics to further our understanding of human behavior within virtual environments, and, thus, producing insights for game design. In addition, the utility of games for learning has been explored. Examples of this work are included in the chapters by Ducheneaut and Yee (Chap. 28), Castranova et al. (Chap. 29), Heeter et al. (Chap. 32) and Plass et al. (Chap. 31).

6 Structure of This Book

The book is divided into several parts, each highlighting a particular aspect of game analytics for development and research, as follows:

-

Part I: An Introduction to Game Analytics introduces the book, its aims and structure. This part will contain four chapters. The first chapter (Introduction), which you are reading now, is a general introduction of the book outlining the different parts and chapters of the book. Chapter 2 (Game Analytics – The Basics) forms the foundation for the book’s chapters, outlining the basics of game analytics, introducing key terminology, outlines fundamental considerations on attribute selection and the role of analytics in game development and the knowledge discovery process. Chapter 3 (The Benefits of Game Analytics: Stakeholders, Contexts and Domains) discusses the benefits of metrics and analytics to the different stakeholders in industry and research. Chapter 4 (Game Industry Metrics Terminology and Analytics Case Study) is a contribution from Tim Fields, a veteran producer, game designer, team leader and business developer, who has been building games professionally since 1994. In his chapter, Tim introduces the terminologies used within the social game industry to outline major metrics used currently within the industry with a case study to supplement the discussion. Chapter 5 (Interview with Jim Baer and Daniel McCaffrey from Zynga) is an interview with Zynga – a company that has been on the forefront of game analytics and its use within social games as an important process to push the business and design of games. This chapter will outline their use of game analytics, the systems they developed and their view of the fields’ future.

-

Part II: Telemetry Collection and Analytics Tools is composed of six chapters, and describes methods for telemetry collection and tools used within the industry for that purpose. In particular, we have five chapters in this part of the book. Chapter 6 (Telemetry and Analytics Best Practices and Lessons Learned) is a contribution from Sony Entertainment discussing a tool they have developed and used within the company for several years to collect and analyze telemetry data within Sony’s pipeline. The chapter outlines best practices after iterating over this system for years. Chapter 7 (Game Development Telemetry in Production) is another industry chapter contributed by Georg Zoeller. In this chapter, he discusses a game analytics system he developed to enable the company to collect and analyze game metrics during production to specifically aid in workflow, quality assurance, bug tracking, and pre-launch design issues. Chapter 8 follows by an interview (Interview with Nicholas Francis and Thomas Hagen from Unity) outlining Unity Technologies’ view of tool development within the Unity 3D platform for telemetry collection and analysis. In addition to how to collect game telemetry, who to collect this data from is of equal importance. Chapter 9 (Sampling for Game User Research) addresses this issue by discussing best practices in sampling, borrowing from social science research and how to best apply such sampling techniques to game development. This chapter is a contribution from Anders Drachen and Magy Seif El-Nasr in collaboration with Andre Gagné, a user researcher at THQ. Next, Chap. 10 (WebTics: A Web Based Telemetry and Metrics System for Small and Medium Games) describes an open source middleware tool under development intended for small-medium scale developers, and discusses telemetry collection from a practical standpoint. This chapter is a contribution from Simon McCallum and Jayson Mackie, both researchers at Gjovik University College, Norway. The part closes with a Chap. 11 (Interview with Darius Kazemi), an interview with Darius Kazemi, a game analytics veteran with over 10 years of experience analyzing game telemetry from games as diverse as casual and AAA titles. The interview focuses on game analytics in general, the current state of the industry and what he sees as the future for analytics in game development.

-

Part III Game Data Analysis, composed of five chapters, addresses analysis methods for the data collected. Specifically, it introduces the subject of datamining as an analysis method: Chapter 12 (Game Data Mining), a contribution from Anders Drachen and Christian Thurau, CTO of Game Analytics, a middleware company delivering game analytics services to the industry, Julian Togelius, Associate professor at The IT University Copenhagen, Georgious Yannakakis, Associate professor at University of Malta, and Christian Bauckhage, professor at the University of Bonn, Germany. The part will also discuss data collection, metrics, telemetry and abstraction of this data to model behavior, which is the subject of Chap. 13 (Meaning in Gameplay: Filtering Variables, Defining Metrics, Extracting Features and Creating Models for Gameplay Analysis), a contribution from Alessandro Canossa. Additionally, this part will also include case studies to show analysis in action: Chapter 14 (Gameplay Metrics in Game User Research: Examples from the Trenches), a contribution from Anders Drachen and Alessandro Canossa with Janus Rau Møller Sørensen, a user research manager at Crystal Dynamics and IO Interactive, worked on titles including Hitman Absolution, Tomb Raider and Deus Ex: Human Revolution, and Chap. 16 (Better Game Experience through Game Metrics: A Rally Videogame Case Study), a contribution from Pietro Guardini, games user researcher at Milestone, who has contributed to several titles, including MotoGP 08 and the Superbike World Championship (SBK), and Paolo Maninetti, senior game programmer at Milestone, who has worked on titles such as MotoGP 08 and the Superbike World Championship (SBK). This part of the book also includes an interview with Aki Järvinen, creative director and competence manager at Digital Chocolate (Chap. 15: Interview with Aki Järvinen from Digital Chocolate), discussing the use of analytics at Digital Chocolate and its role and importance within the company.

-

Part IV: Metrics Visualization deals with visualization methods of game metrics as a way of analyzing data or showing the data to stakeholders. This part has four chapters. The part starts with an introduction to the area of spatial and temporal game analytics which is the subject of Chap. 17 (Spatial Game Analytics). The chapter is a contribution from Anders Drachen with Matthias Shubert who is a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität. The following two chapters delve deeper into case studies with visualization tools for game telemetry analysis. In particular, Chap. 18 (Visual Game Analytics) discusses visual analytics tools developed for Electronic Arts’ Dead Space team, a contribution from Ben Medler, a PhD student at Georgia Tech who worked in collaboration with Electronic Arts as a graduate researcher. Chapter 19 (Visual Analytics tools – A Lens into Player’s Temporal Progression and Behavior) a contribution from Magy Seif El-Nasr, Andre Gagné, a user researcher at THQ, Dinara Moura, PhD student at Simon Fraser University, Bardia Aghabeigi, PhD student at Northeastern University and a game analytics researcher at Blackbird Interactive. The chapter discusses two case studies of visual analytics tools developed for two different games and companies: an RTS game developed by Pixel Ante as a free to play single player game and an RPG game developed by Bioware. The part concludes with Chap. 20 (Interview with Nicklas “Nifflas” Nygren) an interview with an independent game developer working in Sweden and Denmark, that introduces his views, as an indie developer, on game analytics.

-

Part V: Mixed Methods for Game Evaluation, consists of seven chapters addressing multiple methods used for game evaluation. These methods include triangulation techniques for telemetry and qualitative data – subject of Chap. 21 (Contextualizing Data) with case studies from Eric Hazan, a veteran user researcher at Ubisoft and Chap. 22 (Combining Back-End Telemetry Data with Established User Testing Protocols: A Love Story) with case studies from Jordan Lynn a veteran user researcher at Volition, Inc. In addition to triangulation methods, this part also features the use of metrics extracted from surveys as discussed in Chap. 23 (Game Metrics Through Questionnaires), a contribution from Ben Weedon, consultant and manager at PlayableGames, a games user research agency in London, UK. Chapter 25 (Visual Attention and Gaze Behavior in Games: An Object-Based Approach) discusses the use of eye tracking as metrics for game evaluation, a contribution from Veronica Sundstedt, lecturer at Blekinge Institute of Technology, Matthias Bernhard, PhD candidate at Vienna University of Technology, Efstathios Stavrakis, researcher at University of Cyprus, Erik Reinhard, researcher at Max Plank Institute of Informatics, and Michael Wimmer, professor at Vienna University of Technology. Chapter 26 (An Introduction to Physiological Player Metrics for Evaluating Games), a contribution from Lennart Nacke, assistant professor at University of Ontario Institute of Technology, and Chap. 27 (Improving Gameplay with Game Metrics and Player Metrics), a contribution from Graham McAllister, director of Vertical Slice, a game user research company, Pejman Mirza-Babaei, PhD candidate at the University of Sussex, and Jason Avent, Disney Interactive Studios, both investigate the use of psycho-physiological metrics for game evaluation. The part also includes an interview with Simon Møller Chap. 24 (Interview with Simon Møller from Kiloo) creative director at Kiloo, a publisher and independent development company pushing a new model for co-productions. The chapter explores’ the founders perspective on game analytics for mobile development.

-

Part VI: Analytics and Player Communities discusses case studies for understanding social behavior of player communities. Chapter 28 (Data Collection in Massively Multiplayer Online Games: Methods, Analytic Obstacles, and Case Studies) is a contribution by Nic Ducheneaut, senior scientist, and Nick Yee, research scientist, both at PARC. Chapter 29 focuses on general design perspectives (Designer, Analyst, Tinker: How Game Analytics will Contribute to Science), a contribution by Edward Castronova, Travis L. Ross and Issac Knowles, researchers from Indiana University. This part also includes an interview Chap. 30 (Interview with Ola Holmdahl and Ivan Garde from Junebud) with Ola Holmdahl, the founder and CEO of Junebud and Ivan Garde, producer, business and metrics analyst, also at Junebud. This interview explores the use of metrics for web-based MMOGs.

-

Part VII: Metrics and Learning includes two chapters that focus on metrics for pedagogical evaluation. These are Chaps. 31 and 32: Chapter 31 (Metrics in Simulations and Games for Learning) and Chap. 32 (Conceptually Meaningful Metrics: Inferring Optimal Challenge and Mindset from Gameplay). The former is a contribution from Jan Plass, Games for Learning Institute, New York Polytechnic, in collaboration with Bruce D. Homer and Walter Kaczetow from the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center; Charles K. Kinzer and Yoo Kyung Chang from Teachers College Columbia University, and Jonathan Frye, Katherine Isbister and Ken Perlin from New York University. Chapter 32 is a contribution from by Carrie Heeter, professor at Michigan State University and Yu-Hao Lee, PhD student from Michigan State University, with Ben Medler (see title above) and Brian Magerko, assistant professor at Georgia Tech University. In addition to these two chapters, this part of the book features an interview with Simon Egenfeldt Nielsen, CEO of Serious Games Interactive, exploring the use of analytics for serious games from an industry perspective in Chap. 33 (Interview with Simon Egenfeldt Nielsen from Serious Games Interactive).

-

Part VIII: Metrics and Content Generation, discusses the emerging application of game metrics in procedural content generation. Chapter 34 (Metrics for Better Puzzles), by Cameron Browne from the Imperial College London, builds a case for using metrics to generate content in puzzle games.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Additional information

About the Editors

Magy Seif El-Nasr, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in the Colleges of Computer and Information Sciences and Arts, Media and Design, and the Director of Game Educational Programs and Research at Northeastern University, and she also directs the Game User Experience and Design Research Lab. Dr. Seif El-Nasr earned her Ph.D. degree from Northwestern University in Computer Science. Magy’s research focuses on enhancing game designs by developing tools and methods for evaluating and adapting game experiences. Her work is internationally known and cited in several game industry books, including Programming Believable Characters for Computer Games (Game Development Series) and Real-time Cinematography for Games . In addition, she has received several best paper awards for her work. Magy worked collaboratively with Electronic Arts, Bardel Entertainment, and Pixel Ante.

Anders Drachen, Ph.D. is a veteran Data Scientist, currently operating as Lead Game Analyst for Game Analytics (www.gameanalytics.com). He is also affiliated with the PLAIT Lab at Northeastern University (USA) and Aalborg University (Denmark) as an Associate Professor, and sometimes takes on independent consulting jobs. His work in the game industry as well as in data and game science is focused on game analytics, business intelligence for games, game data mining, game user experience, industry economics, business development and game user research. His research and professional work is carried out in collaboration with companies spanning the industry, from big publishers to indies. He writes about analytics for game development on blog.gameanalytics.com, and about game- and data science in general on www.andersdrachen.wordpress.com. His writings can also be found on the pages of Game Developer Magazine and Gamasutra.com.

Alessandro Canossa, Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the College of Arts, Media and Design at Northeastern University, he obtained a MA in Science of Communication from the University of Turin in 1999 and in 2009 he received his PhD from The Danish Design School and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation. His doctoral research was carried out in collaboration with IO Interactive, a Square Enix game development studio, and it focused on user-centric design methods and approaches. His work has been commented on and used by companies such as Ubisoft, Electronic Arts, Microsoft, and Square Enix. Within Square Enix he maintains an ongoing collaboration with IO Interactive, Crystal Dynamics and Beautiful Games Studio.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag London

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Seif El-Nasr, M., Drachen, A., Canossa, A. (2013). Introduction. In: Seif El-Nasr, M., Drachen, A., Canossa, A. (eds) Game Analytics. Springer, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4769-5_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4769-5_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-4471-4768-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-4471-4769-5

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)