Abstract

Substance use disorders represent a global public health issue. This mental health disorder is hypothesized to result from neurobiological changes as a result of chronic drug exposure and clinically manifests as inappropriate behavioral allocation toward the procurement and use of the abused substance and away from other behaviors maintained by more adaptive nondrug reinforcers (e.g., social relationships, work). The dynorphin/kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) is one receptor system that has been altered following chronic exposure to drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, opioids, alcohol) in both laboratory animals and humans, implicating the dynorphin/KOR system in the expression, mechanisms, and treatment of substance use disorders. KOR antagonists have reduced drug self-administration in laboratory animals under certain experimental conditions, but not others. Recently, several human laboratory and clinical trials have evaluated the effectiveness of KOR antagonists as candidate pharmacotherapies for cocaine or tobacco use disorder to test hypotheses generated from preclinical studies. KOR antagonists failed to significantly alter drug use metrics in humans suggesting translational discordance between some preclinical drug self-administration studies and consistent with other preclinical drug self-administration studies that provide concurrent access to an alternative nondrug reinforcer (e.g., food). The implications of this translational discordance and future directions for examining the therapeutic potential of KOR agonists or antagonists as candidate substance use disorder pharmacotherapies are discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Preclinical Evaluation of Candidate Substance Use Disorder Treatments

Substance use disorders (SUDs; i.e., drug addiction) are an insidious and global public health issue. This complex and multifaceted mental health disorder is most commonly modeled in the laboratory using a drug self-administration (SA) procedure to provide an opportunity to measure volitional drug intake. Both preclinical and human laboratory drug SA procedures have made significant contributions to improving our understanding of psychoactive compounds for more than 50 years. In general, preclinical drug SA procedures are used to address two main categories of scientific questions. One category is for abuse liability assessment of psychoactive compounds for potential scheduling as controlled substances by the Drug Enforcement Agency, and there are already excellent reviews on the utility of drug SA procedures for this purpose (Ator and Griffiths 2003; Carter and Griffiths 2009). The other category is for understanding the expression, mechanisms, and treatment of drug-taking behavior as a model of SUDs. This chapter will focus on the use of drug SA procedures to address this latter scientific category.

Although there are infinite iterations of drug SA procedures, all use the classic 3-term contingency of operant conditioning to investigate the stimulus properties of drugs (Skinner 1938). This 3-term contingency can be diagrammed as follows in Eq. (1):

where SD designates a discriminative stimulus, R designates a response on the part of the organism, and SC designates a consequent stimulus. The arrows specify the contingency that, in the presence of the discriminative stimulus SD, performance of response R will deliver the consequent stimulus SC. As a simple example, a rat implanted with a chronic indwelling venous catheter might be connected to an infusion pump containing a dose of a psychoactive drug and placed into an experimental chamber that contains a stimulus light and a response lever. Contingencies can be programmed such that if the stimulus light is illuminated (the discriminative stimulus), then depression of the response lever (the response) will result in delivery of a drug injection (the consequent stimulus). Conversely, if the stimulus light is not illuminated, then responding does not result in the delivery of the drug injection. Under these conditions, subjects typically learn to respond when the discriminative stimulus is present. Consequent stimuli that increase responding leading to their delivery are operationally defined as reinforcers, whereas stimuli that decrease responding leading to their delivery are defined as punishers. The contingencies that relate discriminative stimuli, responses, and consequent stimuli are defined by the schedule of reinforcement (Ferster and Skinner 1957).

Although there are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmacotherapies for some SUDs (e.g., opioid, nicotine, and ethanol), FDA-approved pharmacotherapies are absent for many other classes of abused drugs (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, and cannabis). Moreover, the development of safer and more efficacious medications to treat SUDs remains a priority for both preclinical and human laboratory/clinical drug abuse research. Preclinical evaluation of candidate medication treatment effects on drug SA has demonstrated good, but not perfect, concordance with both medication effects in human laboratory drug SA studies and metrics of drug abuse in clinical trials (Comer et al. 2008; Haney and Spealman 2008a; Mello and Negus 1996).

2 Rationale for Kappa-Opioid Receptors as Candidate SUD Treatments

This chapter will focus on kappa-opioid receptor (KOR) agonist and antagonist effects on preclinical drug SA endpoints. The KOR is a seven transmembrane Gi/o-protein coupled receptor that is ubiquitously expressed in the central and peripheral nervous system and is hypothesized to be involved in mental health disorders including stress, anxiety, depression, and SUD (for review, see Chavkin and Koob 2015; Crowley and Kash 2015; Tejeda and Bonci 2019; Wee and Koob 2010b). In general, KOR activation results in inhibition of neuronal function and can occur following either endogenous release of the dynorphin peptide (Chavkin et al. 1982; Oka et al. 1982) or synthetic KOR agonist administration. For example, administration of synthetic KOR agonists (e.g., U69,593, U50,488, or salvinorin A) decreases extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens (Carlezon et al. 2006; Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Leitl et al. 2014).

Table 1 lists the most prominent KOR agonists and antagonists used in preclinical and clinical research along with the relative selectivity for the KOR over other similar homology receptors such as the mu-opioid (MOR) and delta-opioid (DOR) receptors. In general, the greater the selectivity for KOR over MOR and DOR, the more confidence the result is due to KOR activation or inhibition and not due to an off-target receptor. In addition, the availability of both selective KOR agonists and antagonists allows for sufficient and necessary experimentation in the role of KOR for a specific pharmacological effect. For example, if you were interested in whether activation of KOR receptors by dynorphin was sufficient to decrease mesolimbic dopamine levels, then you could administer a KOR agonist (e.g., salvinorin A) and measure mesolimbic dopamine levels. As mentioned above, this is a reported effect of KOR agonists. However, if you were interested in whether KOR were necessary for salvinorin A to decrease mesolimbic dopamine levels, then you would administer a KOR antagonist before salvinorin A to determine whether salvinorin A decreases mesolimbic dopamine levels. The availability of selective agonists and antagonists allows for rigorous experimentation into the mechanisms associated with or involved in SUDs.

Repeated exposure to several drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, mu-opioid receptor agonists) has been shown to activate or sensitize the endogenous dynorphin/KOR system. This engagement of the dynorphin/KOR system by drugs of abuse has been theorized to contribute to the development of compulsive drug use and SUD (Chavkin and Koob 2015; Shippenberg et al. 2007). For example, polymorphisms of prodynorphin have been correlated with increased diagnosis of opioid use disorder (Clarke et al. 2012). In addition, both increased dynorphin expression and KOR density have been observed in cocaine overdose patients (Hurd and Herkenham 1993; Staley et al. 1997). Furthermore, cocaine SA leads to a reduction in KOR availability in humans as measured using positron-emission tomography (Martinez et al. 2019). Consistent with these clinical data, a history of either heroin or cocaine SA under extended access conditions increases prodynorphin expression in the nucleus accumbens shell of rats or monkeys (Daunais et al. 1993; Fagergren et al. 2003; Schlosburg et al. 2013; Solecki et al. 2009). These results have been interpreted to suggest that chronic KOR activation is one key neurobiological system mediating the progression from drug abuse to severe SUD (Koob and Moal 2008; Wee and Koob 2010a). Table 2 summarizes the 34 publications that have examined either acute or chronic (i.e., repeated administration for at least 3 days) treatment effects of KOR agonists or antagonists in preclinical drug SA procedures. The predominant drugs of abuse examined have been cocaine (44%), ethanol (35%), and opioids (24%). The predominant research subjects have been rats (74%) and rhesus monkeys (26%); most studies only involved male subjects (~76%). The results and implication of this literature will be reviewed in more detail below.

3 KOR Agonist Effects on Preclinical Drug SA

KOR agonists and drugs of abuse appear to produce opposing effects on both abuse-related neurochemical and behavioral endpoints. For example, KOR agonists decrease mesolimbic dopamine levels in rats (Devine et al. 1993; Donzanti et al. 1992; Leitl et al. 2014; Spanagel et al. 1990), produce dysphoric subjective effects in humans (Pfeiffer et al. 1986; Walsh et al. 2001), and fail to function as positive reinforcers in rodent and nonhuman primate drug SA procedures (Marinelli et al. 1998; Negus et al. 2008; Tang and Collins 1985; Townsend et al. 2017; Woods and Gmerek 1985). This line of research led to the hypothesis that KOR agonists may have clinical utility as candidate SUD pharmacotherapies by either punishing drug-taking behavior if the KOR agonist and the drug of abuse were combined or antagonizing the abuse-related effects of central nervous system-active drugs if the KOR agonist was administered as an acute or repeated pretreatment to subsequent drug-taking behavior. Two general types of experiments have been conducted examining the effects of KOR agonists on drug SA.

3.1 Preclinical SA of KOR Agonists and Drug of Abuse Combinations

One type of experiment involves combining a KOR agonist and the drug of abuse in the same syringe for SA to determine whether the KOR agonist would function as a punisher (i.e., presentation of the stimulus (KOR agonist) decreases the probability of the preceding behavior). Thus, the research animal would self-administer a mixture of KOR agonist and drug of abuse. Based on the literature cited above, the hypothesis for these studies would be that the KOR agonist mixed with the drug of abuse would lead to a decrease in rates of drug SA. Three studies (#1–3 in Table 2) have examined combining a KOR agonist and cocaine (Freeman et al. 2014) or a MOR agonist (Negus et al. 2008; Townsend et al. 2017). All three studies reported that mixtures of the abused drug and KOR agonist were less reinforcing (i.e., maintained lower rates of operant responding) than the abused drug alone. These results have been interpreted to suggest that clinical combinations of MOR agonists and KOR agonists might retain the therapeutic desirable effects (e.g., analgesia) of MOR agonists with reduced undesirable effects (e.g., abuse liability). However, illicit drug manufacturers or dealers are unlikely to adulterate their product with something that would deter abuse liability.

3.2 KOR Agonists as Pretreatments to Preclinical Drug of Abuse SA

A second type of experiment has examined either acute KOR agonist pretreatment to a single drug SA or repeated KOR agonist treatment effects across multiple days of drug SA. The studies that employed a repeated dosing procedure were modeling aspects of repeated candidate medication administration utilized in human laboratory studies, clinical trials, and clinical prescribing patterns for current FDA-approved treatments for SUDs (e.g., buprenorphine, methadone, varenicline, and naltrexone). Thirteen studies (#4–16 in Table 2) have examined the effects of either acute or repeated KOR agonist treatment on drug SA in mice, rats, and rhesus monkeys. Acute administration of U50,488 (Glick et al. 1995), U69,593 (Schenk et al. 1999; Schenk et al. 2001), cyclazocine (Glick et al. 1998), spiradoline (Glick et al. 1995), and enadoline (Bowen et al. 2003; Hölter et al. 2000) has been reported to decrease rates of cocaine, morphine, and ethanol SA in both rats and rhesus monkeys. These results were interpreted as evidence that KOR agonists may have clinical utility as candidate medications for SUD treatment.

However, when KOR agonist effects on drug SA were examined under repeated dosing conditions, a more complicated profile of effects emerged compared to the acute KOR agonist pretreatment studies described above. For example, repeated ethylketocyclazine, U50,488, enadoline, spiradoline, PD117302, bremazocine, and cyclazocine treatments all produced sustained decreases in rates of cocaine and ethanol SA in rhesus monkeys (Cosgrove and Carroll 2002; Mello and Negus 1998; Negus et al. 1997). Repeated bremazocine, but not U50,488, produced sustained decreases in rates of ethanol SA in rats (Nestby et al. 1999). Repeated U50,488 treatment significantly decreased rates of nicotine SA in rats on the third day of treatment and without altering food-maintained responding (Ismayilova and Shoaib 2010). However, the KOR agonist doses that decreased drug SA also decreased rates of food-maintained responding when food-maintained responding was assessed (Cosgrove and Carroll 2002; Mello and Negus 1998; Negus et al. 1997). Thus, repeated KOR agonist treatment effects were not behaviorally selective for drug vs. nondrug reinforcers and suggestive of overall depression of behavior. In contrast to these results, repeated enadoline treatment increased rates of ethanol SA in rats (Hölter et al. 2000) and repeated U50,488 treatment shifted both cocaine and morphine SA dose-effect functions to the left in rats (Kuzmin et al. 1997). Furthermore, when repeated U50,488 treatment effects were examined on cocaine SA in rhesus monkeys under conditions where there was an alternative nondrug food reinforcer available concurrently to intravenous cocaine injections, repeated U50,488 increased cocaine “choice” and decreased food “choice” (Negus 2004). Consistent with these later results, repeated enadoline treatment failed to attenuate cocaine vs. money choice in humans, and there was a trend for increased cocaine choice at the largest enadoline dose examined (Walsh et al. 2001). No double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials examining KOR agonists as candidate pharmacotherapies for SUD treatment have been published.

In summary, the effects of KOR agonists on preclinical drug SA studies and the single human laboratory drug SA study have thus far generated three main findings. First, when KOR agonists are mixed with the abuse drug and co-administered, KOR agonists can function as punishers and decrease SA of the abused drug. Second, acute pretreatment with a KOR agonist decreased rates of drug SA across a broad range of abused drug classes (e.g. cocaine, ethanol, morphine). Lastly, repeated KOR agonist treatment either decreased rates of abused drug SA typically at doses that also decreased rates of food-maintained responding or increases rates of drug SA including under a drug vs. food choice procedure. Overall, this body of preclinical literature does not support the clinical utility of KOR agonists as candidate SUD treatments.

4 KOR Antagonist Effects on Preclinical Drug Self-Administration

One prominent and emerging SUD theory is that chronic exposure to drugs of abuse and withdrawal produces a “motivational withdrawal syndrome” that increases the magnitude and alters the mechanisms of drug reinforcement and serves as “one of the driving factors of compulsivity in addiction” (Koob and Mason 2016). Chronic exposure to drugs of abuse is hypothesized to alter the state of the patient or research subject and thereby alter the mechanisms of and increase the magnitude of drug reinforcement. For example, opioid abuse often leads to physical dependence, and opioid withdrawal in dependent subjects increases the reinforcing effects of opioids, decreases the reinforcing efficacy of nondrug reinforcers like food, and promotes a maladaptive allocation of behavior toward further drug use at the expense of behaviors maintained by more adaptive behaviors. Specifically, chronic drug exposure has been shown to (1) decrease basal activity of dopamine and/or opioid reward systems and (2) recruit activation of other neural systems, sometimes described as “stress” or “anti-reward” systems, that involve neurotransmitters including corticotropic releasing factor (CRF) and dynorphin (Koob and Mason 2016; Koob and Moal 2008; Koob and Volkow 2009). Overall, consumption of any abused drug dose is hypothesized to produce an initial increase in dopamine/opioid signaling as drug levels rise and peak, followed by a longer period of depressed dopamine/opioid signaling and enhanced stress hormone signaling that together mediate negative affective states of drug withdrawal. Increasingly intensive regimens of abused drug exposure are hypothesized to produce a cumulative increase in the later effects and increasingly intense aversive subjective states. Under these circumstances, drug-induced reinforcing effects are often described as “negative,” because the drug is now hypothesized to produce its reinforcing effects not by increasing dopamine/opioid signaling from a normal basal level but rather by alleviating the aversive state produced by a depressed reward system and activated stress system; however, this interpretation is not consistent with the operational definition of negative reinforcement (i.e., response requirement completion results in removal of SC proposed by Skinner (1938)). The subject in a drug SA procedure is responding to receive the drug injection (SC) which is positive reinforcement and not the removal of some hypothesized internal state (Negus and Banks 2018).

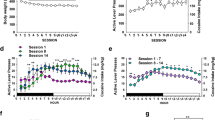

Evidence to support this hypothesized transition comes in part from preclinical rat drug SA studies that have used single-operant drug SA procedures in which the primary dependent measure is the rate of drug SA. Two observations have been seminal in support of this hypothesized transition. First, the recruitment of negative reinforcement processes that occurs with extended drug SA is hypothesized to not only modify the mechanisms of drug reinforcement but also to increase its magnitude (i.e., by summing positive and negative reinforcement mechanisms). In support of this hypothesis, regiments of “extended access” (produced by increasing the number of hours per day that subjects can self-administer drug) have been shown to increase rates of SA, a phenomenon referred to as “escalation” (Koob and Kreek 2007). Second, the recruitment of these negative reinforcement processes is also hypothesized to render drug SA sensitive to experimental manipulations that attenuate the KOR/stress system signaling. For example, dynorphin acting at KOR is one stress-related neurotransmitter implicated in “negative reinforcement” processes, and KOR antagonists such as nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) and CERC-501 have been reported to block escalated rates of cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and ethanol SA in rats (Domi et al. 2018; Schlosburg et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2011; Wee et al. 2009; Wee et al. 2012; Whitfield et al. 2015). Furthermore, KOR antagonists do not attenuate cocaine, methamphetamine, or heroin SA under more limited (~1–2 h) drug access conditions in both rats (Deehan et al. 2012; Doyon et al. 2006; Glick et al. 1995; Hölter et al. 2000; Liu and Jernigan 2011; Negus et al. 1993) and rhesus monkeys (Negus 2004; Negus et al. 1997) suggesting that the recruitment of the dynorphin/KOR system only occurs during extended drug access conditions. Although the effectiveness of KOR antagonists to alter drug SA appears to be dependent on the length of the drug SA session for MOR agonists and monoamine transporter ligands (cocaine and methamphetamine; Table 2), the literature suggests the same principle does not necessarily hold true for ethanol. For example, under limited ethanol access conditions, KOR antagonists have been shown to increase (Mitchell et al. 2005), have no effect (Deehan et al. 2012; Doyon et al. 2006), or decrease (Cashman and Azar 2014; Rorick-Kehn et al. 2014; Schank et al. 2012) ethanol SA in rats. Overall, one implication of this literature is that different classes of abused drugs might recruit the dynorphin/KOR system in different manners.

4.1 KOR Antagonist Effects on Preclinical Drug Choice SA

However, these KOR antagonist treatment effects on preclinical drug SA endpoints have not translated when evaluated in nonhuman primates or humans. For example, in opioid-dependent rhesus monkeys, the KOR antagonist 5′-guanidinaltrindole (GNTI) failed to attenuate opioid withdrawal-associated increases in opioid vs. food choice (Negus and Rice 2009). In addition, nor-BNI failed to attenuate both rates of cocaine SA during extended cocaine access sessions and cocaine vs. food choice in rhesus monkeys self-administering cocaine 22-h per day (Hutsell et al. 2016). Whether these differences in KOR antagonist effects are due to species differences between rats and rhesus monkeys or procedural differences in the drug SA schedule or reinforcement remain unexplored scientific space.

4.2 KOR Antagonist Effects on Human Drug SA Metrics

In humans, buprenorphine plus naloxone and naltrexone maintenance, combined to produce a KOR antagonist effect, failed to attenuate cocaine use in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centered clinical trial (Ling et al. 2016). Repeated LY2456302 treatment also failed to attenuate cocaine craving in humans (Reed et al. 2017). Furthermore, CERC-501 (i.e., LY2456301) failed to attenuate cigarette smoking, craving, or nicotine withdrawal in humans (Jones et al. 2019). Moreover, a recent positron-emission tomography study examining KOR binding in healthy controls and cocaine abusers reported no significant differences in KOR binding in any brain region examined (Martinez et al. 2019). These results suggest that a history of repeated cocaine exposure and a diagnosis of cocaine use disorder were not sufficient to alter KOR binding in humans and are in contrast to previous results in cocaine overdose patients using autoradiography methods (Hurd and Herkenham 1993; Staley et al. 1997). Reasons for differences between the in vivo positron-emission tomography study and the postmortem mRNA and autoradiography study are not presently clear but could be related to the affinity of the ligands for different KOR subtypes or states (i.e., high vs. low affinity). In summary, the promising results of KOR antagonists in preclinical rodent models of cocaine use disorder have so far failed to translate when evaluated in higher-order species such as nonhuman primates or humans and on endpoints that focus on behavioral allocation between drug and nondrug reinforcers instead of rates of drug-taking behavior.

5 Conclusions and Future Directions

Over the past two decades, preclinical research has improved our understanding of the role of KOR in the expression, mechanisms, and treatment of SUD. Converging lines of evidence from both preclinical and human studies support the conclusion that chronic abused drug exposure changes the dynorphin/KOR system. Furthermore, mixtures of MOR and KOR agonists (Freeman et al. 2014; Negus et al. 2008; Townsend et al. 2017) or mixed-action MOR/KOR agonists such as pentazocine (Hoffmeister 1979) appear to have reduced abuse-related effects compared to MOR agonists. However, both KOR agonist and KOR antagonist treatments have thus far failed to significantly alter metrics of cocaine use in humans. Unfortunately, there are no published human laboratory drug SA studies or clinical trials evaluating KOR agonist or antagonist effects on other SUDs, such as methamphetamine, opioids, ethanol, or tobacco. CERC-501 is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a candidate medication for tobacco smoking and smoking relapse (Helal et al. 2017). The evaluation of candidate medication effects in SUD patients provides critical reverse translational feedback to improve the predictive validity of preclinical SUD models. However, the results of KOR agonists and antagonists in cocaine use disorder and tobacco use disorder patients thus far fail to support the continued development and evaluation of novel chemical entities targeting the dynorphin/KOR system as candidate SUD pharmacotherapies. There are presently no published clinical data on the effectiveness of KOR antagonists for alcohol or opioid use disorder.

In the broader preclinical drug abuse literature, there are two experimental features that appear to promote accurate translation of preclinical-to-clinical results. First, repeated treatment with the candidate medication to match the subchronic-to-chronic treatment regimens commonly employed in clinical SUD treatment (Czoty et al. 2016; Haney and Spealman 2008b; Mello and Negus 1996). The effects of acute vs. repeated KOR agonists on preclinical drug SA endpoints reviewed above are consistent with this conclusion. However, the examination of repeated KOR antagonist effects on drug SA endpoints has been problematic because most currently available KOR antagonists are irreversible or receptor-inactivating antagonists (Butelman et al. 1993, 1998; Schmid et al. 2013). The long duration of action of irreversible KOR antagonists complicates dose titration and potentially increases the risk of off-target undesirable effects. The development of short-acting KOR antagonists CERC-501 (i.e., LY2456302) (Helal et al. 2017; Reed et al. 2017) has facilitated clinical SUD research to provide necessary feedback regarding hypotheses developed using preclinical drug SA procedures. Second, assessment of candidate medication effects in preclinical drug SA procedures that use behavioral allocation between the target drug of abuse and an alternative nondrug reinforcer (e.g., food or social) rather than rates of drug SA behavior has shown strong translational concordance with clinical results (for review, see Banks et al. 2015; Banks and Negus 2012, 2017). A critical step in efficiently evaluating candidate SUD medications is the utilization of preclinical testing procedures that are both sensitive to FDA-approved medications (if available) and selective for those positive controls in comparison to active negative controls known to be clinically ineffective (Banks et al. 2019). Given the human laboratory and clinical literature cited above in Sects. 3 and 4, both KOR agonists and KOR antagonists could function as active negative controls, but should not continued to be evaluated as candidate OUD medications (Rasmussen et al. 2019).

References

Ator NA, Griffiths RR (2003) Principles of drug abuse liability assessment in laboratory animals. Drug Alcohol Depend 70:S55–S72

Banks ML, Negus SS (2012) Preclinical determinants of drug choice under concurrent schedules of drug self-administration. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2012:281768

Banks ML, Negus SS (2017) Insights from preclinical choice models on treating drug addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38:181–194

Banks ML, Hutsell BA, Schwienteck KL, Negus SS (2015) Use of preclinical drug vs. food choice procedures to evaluate candidate medications for cocaine addiction. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2:136–150

Banks ML, Townsend EA, Negus SS (2019) Testing the 10 most wanted: a preclinical algorithm to screen candidate opioid use disorder medications. Neuropsychopharmacology

Bowen CA, Negus SS, Zong R, Neumeyer JL, Bidlack JM, Mello NK (2003) Effects of mixed-action κ/μ opioids on cocaine self-administration and cocaine discrimination by rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:1125–1139

Butelman ER, Negus SS, Ai Y, de Costa BR, Woods JH (1993) Kappa opioid antagonist effects of systemically administered nor-binaltorphimine in a thermal antinociception assay in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267:1269–1276

Butelman ER, Ko M-C, Sobczyk-Kojiro K, Mosberg HI, Van Bemmel B, Zernig G, Woods JH (1998) Kappa-opioid receptor binding populations in rhesus monkey brain: relationship to an assay of thermal antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285:595–601

Carlezon WA, Béguin C, DiNieri JA, Baumann MH, Richards MR, Todtenkopf MS, Rothman RB, Ma Z, Lee DY-W, Cohen BM (2006) Depressive-like effects of the κ-opioid receptor agonist salvinorin A on behavior and neurochemistry in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316:440–447

Carter LP, Griffiths RR (2009) Principles of laboratory assessment of drug abuse liability and implications for clinical development. Drug Alcohol Depend 105(Suppl 1):S14–S25

Cashman JR, Azar MR (2014) Potent inhibition of alcohol self-administration in alcohol-preferring rats by a κ-opioid receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 350:171–180

Chavkin C, Koob GF (2015) Dynorphin, dysphoria, and dependence: the stress of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:373

Chavkin C, James I, Goldstein A (1982) Dynorphin is a specific endogenous ligand of the kappa opioid receptor. Science 215:413–415

Clarke T-K, Ambrose-Lanci L, Ferraro TN, Berrettini WH, Kampman KM, Dackis CA, Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Oslin DW, Lohoff FW (2012) Genetic association analyses of PDYN polymorphisms with heroin and cocaine addiction. Genes Brain Behav 11:415–423

Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL (2008) The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend 96:1–15

Cosgrove KP, Carroll ME (2002) Effects of bremazocine on self-administration of smoked cocaine base and orally delivered ethanol, phencyclidine, saccharin, and food in rhesus monkeys: a behavioral economic analysis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 301:993–1002

Crowley NA, Kash TL (2015) Kappa opioid receptor signaling in the brain: circuitry and implications for treatment. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 62:51–60

Czoty PW, Stoops WW, Rush CR (2016) Evaluation of the “Pipeline” for development of medications for cocaine use disorder: a review of translational preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical trial research. Pharmacol Rev 68:533–562

Daunais JB, Roberts DC, McGinty JF (1993) Cocaine self-administration increases preprodynorphin, but not c-fos, mRNA in rat striatum. Neuroreport 4:543–546

Deehan GA, McKinzie DL, Carroll FI, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA (2012) The long-lasting effects of JDTic, a kappa opioid receptor antagonist, on the expression of ethanol-seeking behavior and the relapse drinking of female alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 101:581–587

Devine DP, Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA (1993) Differential involvement of ventral tegmental mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors in modulation of basal mesolimbic dopamine release: in vivo microdialysis studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 266:1236–1246

Di Chiara G, Imperato A (1988) Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:5274–5278

Domi E, Barbier E, Augier E, Augier G, Gehlert D, Barchiesi R, Thorsell A, Holm L, Heilig M (2018) Preclinical evaluation of the kappa-opioid receptor antagonist CERC-501 as a candidate therapeutic for alcohol use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 43:1805–1812

Donzanti BA, Althaus JS, Payson MM, Von Voigtlander PF (1992) Kappa agonist-induced reduction in dopamine release: site of action and tolerance. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 78:193–210

Doyon WM, Howard EC, Shippenberg TS, Gonzales RA (2006) κ-Opioid receptor modulation of accumbal dopamine concentration during operant ethanol self-administration. Neuropharmacology 51:487–496

Fagergren P, Smith HR, Daunais JB, Nader MA, Porrino LJ, Hurd YL (2003) Temporal upregulation of prodynorphin mRNA in the primate striatum after cocaine self-administration. Eur J Neurosci 17:2212–2218

Ferster C, Skinner B (1957) Schedules of reinforcement. Appleton-Century-Croft, New York

Freeman KB, Naylor JE, Prisinzano TE, Woolverton WL (2014) Assessment of the kappa opioid agonist, salvinorin A, as a punisher of drug self-administration in monkeys. Psychopharmacology 231:2751–2758

Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Raucci J, Sydney A (1995) Kappa opioid inhibition of morphine and cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res 681:147–152

Glick SD, Visker KE, Maisonneuve IM (1998) Effects of cyclazocine on cocaine self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 357:9–14

Haney M, Spealman R (2008a) Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology 199:403–419

Haney M, Spealman R (2008b) Controversies in translational research: drug self-administration. Psychopharmacology 199:403–419

Helal MA, Habib ES, Chittiboyina AG (2017) Selective kappa opioid antagonists for treatment of addiction, are we there yet? Eur J Med Chem 141:632–647

Hoffmeister F (1979) Progressive-ratio performance in the rhesus monkey maintained by opiate infusions. Psychopharmacology 62:181–186

Hölter SM, Henniger MSH, Lipkowski AW, Spanagel R (2000) Kappa-opioid receptors and relapse-like drinking in long-term ethanol-experienced rats. Psychopharmacology 153:93–102

Hunter JC, Leighton GE, Meecham KG, Boyle SJ, Horwell DC, Rees DC, Hughes J (1990) CI-977, a novel and selective agonist for the κ-opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 101:183–189

Hurd YL, Herkenham M (1993) Molecular alterations in the neostriatum of human cocaine addicts. Synapse 13:357–369

Hutsell BA, Cheng K, Rice KC, Negus SS, Banks ML (2016) Effects of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) on cocaine versus food choice and extended-access cocaine intake in rhesus monkeys. Addict Biol 00:360–373

Ismayilova N, Shoaib M (2010) Alteration of intravenous nicotine self-administration by opioid receptor agonist and antagonists in rats. Psychopharmacology 210:211–220

Jones JD, Babalonis S, Marcus R, Vince B, Kelsh D, Lofwall MR, Fraser H, Paterson B, Martinez S, Martinez DM, Nunes EV, Walsh SL, Comer SD (2019) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist, CERC-501, in a human laboratory model of smoking behavior. Addict Biol 0: e12799

Koob GF, Kreek MJ (2007) Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatr 164:1149–1159

Koob GF, Mason BJ (2016) Existing and future drugs for the treatment of the dark side of addiction. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 56:299–322

Koob GF, Moal ML (2008) Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu Rev Psychol 59:29–53

Koob GF, Volkow ND (2009) Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:217

Kuzmin AV, Semenova S, Gerrits MAFM, Zvartau EE, Van Ree JM (1997) κ-Opioid receptor agonist U50,488H modulates cocaine and morphine self-administration in drug-naive rats and mice. Eur J Pharmacol 321:265–271

Kuzmin AV, Gerrits MA, Van Ree JM (1998) Kappa-opioid receptor blockade with nor-binaltorphimine modulates cocaine self-administration in drug-naive rats. Eur J Pharmacol 358:197–202

Leitl MD, Onvani S, Bowers MS, Cheng K, Rice KC, Carlezon WA Jr, Banks ML, Negus SS (2014) Pain-related depression of the mesolimbic dopamine system in rats: expression, blockade by analgesics, and role of endogenous kappa-opioids. Neuropsychopharmacology 39:614–624

Ling W, Hillhouse MP, Saxon AJ, Mooney LJ, Thomas CM, Ang A, Matthews AG, Hasson A, Annon J, Sparenborg S, Liu DS, McCormack J, Church S, Swafford W, Drexler K, Schuman C, Ross S, Wiest K, Korthuis PT, Lawson W, Brigham GS, Knox PC, Dawes M, Rotrosen J (2016) Buprenorphine + naloxone plus naltrexone for the treatment of cocaine dependence: the cocaine use reduction with buprenorphine (CURB) study. Addiction 111:1416–1427

Liu X, Jernigan C (2011) Activation of the opioid μ1, but not δ or κ, receptors is required for nicotine reinforcement in a rat model of drug self-administration. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35:146–153

Marinelli M, Barrot M, Simon H, Oberlander C, Dekeyne A, Moal ML, Piazza PV (1998) Pharmacological stimuli decreasing nucleus accumbens dopamine can act as positive reinforcers but have a low addictive potential. Eur J Neurosci 10:3269–3275

Martinez D, Slifstein M, Matuskey D, Nabulsi N, Zheng M-Q, Lin S-f, Ropchan J, Urban N, Grassetti A, Chang D, Salling M, Foltin R, Carson RE, Huang Y (2019) Kappa-opioid receptors, dynorphin, and cocaine addiction: a positron emission tomography study. Neuropsychopharmacology

Mello NK, Negus SS (1996) Preclinical evaluation of pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine and opioid abuse using drug self-administration procedures. Neuropsychopharmacology 14:375–424

Mello NK, Negus SS (1998) Effects of kappa opioid agonists on cocaine- and food-maintained responding by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 286:812–824

Mitchell JM, Liang MT, Fields HL (2005) A single injection of the kappa opioid antagonist norbinaltorphimine increases ethanol consumption in rats. Psychopharmacology 182:384–392

Morales M, Anderson RI, Spear LP, El V (2014) Effects of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist, norbinaltorphimine, on ethanol intake: impact of age and sex. Dev Psychobiol 56:700–712

Munro TA, Huang X-P, Inglese C, Perrone MG, Van't Veer A, Carroll FI, Béguin C, Carlezon WA Jr, Colabufo NA, Cohen BM, Roth BL (2013) Selective κ opioid antagonists nor-BNI, GNTI and JDTic have low affinities for non-opioid receptors and transporters. PLoS One 8:e70701

Nagase H, Imaide S, Hirayama S, Nemoto T, Fujii H (2012) Essential structure of opioid κ receptor agonist nalfurafine for binding to the κ receptor 2: synthesis of decahydro(iminoethano)phenanthrene derivatives and their pharmacologies. Bioorg Med Chem Letts 22:5071–5074

Negus SS (2004) Effects of the kappa opioid agonist U50,488 and the kappa opioid antagonist nor-binaltorphimine on choice between cocaine and food in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 176:204–213

Negus SS, Banks ML (2018) Modulation of drug choice by extended drug access and withdrawal in rhesus monkeys: implications for negative reinforcement as a driver of addiction and target for medications development. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 164:32–39

Negus SS, Rice KC (2009) Mechanisms of withdrawal-associated increases in heroin self-administration: pharmacologic modulation of heroin vs food choice in heroin-dependent rhesus monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:899–911

Negus SS, Henriksen SJ, Mattox A, Pasternak GW, Portoghese PS, Takemori AE, Weinger MB, Koob GF (1993) Effect of antagonists selective for mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors on the reinforcing effects of heroin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265:1245–1252

Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lin C-E (1997) Effects of kappa opioids on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:44–55

Negus SS, Schrode K, Stevenson GW (2008) Mu/kappa opioid interactions in rhesus monkeys: implications for analgesia and abuse liability. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 16:386–399

Nestby P, Schoffelmeer ANM, Homberg JR, Wardeh G, De Vries TJ, Mulder AH, Vanderschuren LJMJ (1999) Bremazocine reduces unrestricted free-choice ethanol self-administration in rats without affecting sucrose preference. Psychopharmacology 142:309–317

Oka T, Negishi K, Suda M, Sawa A, Fujino M, Wakimasu M (1982) Evidence that dynorphin-(1–13) acts as an agonist on opioid κ-receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 77:137–141

Pfeiffer A, Brantl V, Herz A, Emrich H (1986) Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science 233:774–776

Rasmussen K, White DA, Acri JB (2019) NIDA’s medication development priorities in response to the opioid crisis: ten most wanted. Neuropsychopharmacology 44:657–659

Raynor K, Kong H, Chen Y, Yasuda K, Yu L, Bell GI, Reisine T (1994) Pharmacological characterization of the cloned kappa-, delta-, and mu-opioid receptors. Mol Pharmacol 45:330–334

Reed B, Butelman ER, Fry RS, Kimani R, Kreek MJ (2017) Repeated administration of opra kappa (LY2456302), a novel, short-acting, selective KOP-r antagonist, in persons with and without cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 43:739

Rorick-Kehn LM, Witkin JM, Statnick MA, Eberle EL, McKinzie JH, Kahl SD, Forster BM, Wong CJ, Li X, Crile RS, Shaw DB, Sahr AE, Adams BL, Quimby SJ, Diaz N, Jimenez A, Pedregal C, Mitch CH, Knopp KL, Anderson WH, Cramer JW, McKinzie DL (2014) LY2456302 is a novel, potent, orally-bioavailable small molecule kappa-selective antagonist with activity in animal models predictive of efficacy in mood and addictive disorders. Neuropharmacology 77:131–144

Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R, Siebert D, Rice KC, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Rothman RB (2002) Salvinorin A: a potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous κ opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:11934–11939

Schank JR, Goldstein AL, Rowe KE, King CE, Marusich JA, Wiley JL, Carroll FI, Thorsell A, Heilig M (2012) The kappa opioid receptor antagonist JDTic attenuates alcohol seeking and withdrawal anxiety. Addict Biol 17:634–647

Schenk S, Partridge B, Shippenberg TS (1999) U69593, a kappa-opioid agonist, decreases cocaine self-administration and decreases cocaine-produced drug-seeking. Psychopharmacology 144:339–346

Schenk S, Partridge B, Shippenberg TS (2001) Effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist, U69593, on the development of sensitization and on the maintenance of cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 24:441

Schlosburg JE, Whitfield TW, Park PE, Crawford EF, George O, Vendruscolo LF, Koob GF (2013) Long-term antagonism of κ opioid receptors prevents escalation of and increased motivation for heroin intake. J Neurosci 33:19384–19392

Schmid CL, Streicher JM, Groer CE, Munro TA, Zhou L, Bohn LM (2013) Functional selectivity of 6′-guanidinonaltrindole (6′-GNTI) at κ-opioid receptors in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem 288:22387–22398

Shippenberg TS, Zapata A, Chefer VI (2007) Dynorphin and the pathophysiology of drug addiction. Pharmacol Ther 116:306–321

Skinner B (1938) The behavior of organisms. Appleton-Century-Crofts, New York

Solecki W, Ziolkowska B, Krowka T, Gieryk A, Filip M, Przewlocki R (2009) Alterations of prodynorphin gene expression in the rat mesocorticolimbic system during heroin self-administration. Brain Res 1255:113–121

Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS (1990) The effects of opioid peptides on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem 55:1734–1740

Staley JK, Rothman RB, Rice KC, Partilla J, Mash DC (1997) κ2 opioid receptors in limbic areas of the human brain are upregulated by cocaine in fatal overdose victims. J Neurosci 17:8225–8233

Tang AH, Collins RJ (1985) Behavioral effects of a novel kappa opioid analgesic, U-50488, in rats and rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 85:309–314

Tejeda HA, Bonci A (2019) Dynorphin/kappa-opioid receptor control of dopamine dynamics: Implications for negative affective states and psychiatric disorders. Brain Res 1713:91–101

Townsend EA, Naylor JE, Negus SS, Edwards SR, Qureshi HN, McLendon HW, McCurdy CR, Kapanda CN, do Carmo JM, da Silva FS, Hall JE, Sufka KJ, Freeman KB (2017) Effects of nalfurafine on the reinforcing, thermal antinociceptive, and respiratory-depressant effects of oxycodone: modeling an abuse-deterrent opioid analgesic in rats. Psychopharmacology 234:2597–2605

Walker BM, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF (2011) Systemic κ-opioid receptor antagonism by nor-binaltorphimine reduces dependence-induced excessive alcohol self-administration in rats. Addict Biol 16:116–119

Walsh SL, Geter-Douglas B, Strain EC, Bigelow GE (2001) Enadoline and butorphanol: evaluation of κ-agonists on cocaine pharmacodynamics and cocaine self-administration in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299:147–158

Wee S, Koob G (2010a) The role of the dynorphin–κ opioid system in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse. Psychopharmacology 210:121–135

Wee S, Koob GF (2010b) The role of the dynorphin–κ opioid system in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse. Psychopharmacology 210:121–135

Wee S, Orio L, Ghirmai S, Cashman J, Koob G (2009) Inhibition of kappa opioid receptors attenuated increased cocaine intake in rats with extended access to cocaine. Psychopharmacology 205:565–575

Wee S, Vendruscolo LF, Misra KK, Schlosburg JE, Koob GF (2012) A combination of buprenorphine and naltrexone blocks compulsive cocaine intake in rodents without producing dependence. Science Transl Med 4:146ra110

Whitfield TW, Schlosburg JE, Wee S, Gould A, George O, Grant Y, Zamora-Martinez ER, Edwards S, Crawford E, Vendruscolo LF, Koob GF (2015) κ opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell mediate escalation of methamphetamine intake. J Neurosci 35:4296–4305

Woods JH, Gmerek DE (1985) Substitution and primary dependence studies in animals. Drug Alcohol Depend 14:233–247

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Banks, M.L. (2019). The Rise and Fall of Kappa-Opioid Receptors in Drug Abuse Research. In: Nader, M., Hurd, Y. (eds) Substance Use Disorders. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol 258. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2019_268

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/164_2019_268

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33678-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33679-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)