Abstract

In this chapter, Rosen, Scott, and DeOrnellas define bullying, identify different subtypes of peer aggression, and discuss prevalence rates with attention to gender and grade level. Both being bullied and bullying others are associated with negative physical health, mental health, and school outcomes, and the literature outlining these associations is presented. The majority of bullying incidents occur in the school setting, and thus school staff plays a critical role in the identification, prevention, and intervention of bullying behaviors. This chapter introduces the overarching theme of how multiple perspectives of key school staff (i.e., teachers, principals, school resource officers, school psychologists/counselors, nurses, and coaches) can provide a more complete understanding of this phenomenon, which can in turn lead to the development of more effective prevention and intervention programs.

“For two years, Johnny, a quiet 13-year-old, was a human plaything for some of his classmates. The teenagers badgered Johnny for money,… beat him up in the rest room and tied a string around his neck, leading him around as a ‘pet’. When Johnny’s torturers were interrogated about the bullying, they said they pursued their victim because it was fun” (Olweus, 1995, p. 196 drawing from a newspaper clipping).

“In conclusion, there is no conclusion to what children who are bullied live with. They take it home with them at night. It lives inside them and eats away at them. It never ends. So neither should our struggle to end it” (Sarah, age 16, sharing her reflections on the bullying she has endured, Hymel & Swearer, 2015, p. 296).

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Experiences of peer maltreatment like those depicted in the opening vignettes are far too common an occurrence in schools worldwide. Being bullied can be tremendously painful, and victimization has been associated with a myriad of adjustment problems (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). Not only do victimized youth suffer, but aggressive youth are also at increased risk for maladjustment (Coyne, Nelson, & Underwood, 2011). Fortunately, bullying has become an issue of growing concern for educators as there is increasing awareness that bullying has the potential to negatively impact all members of the school community.

The overarching theme of this book is that the multiple perspectives of key school staff (i.e., teachers, principals, school resource officers, school psychologists/counselors, nurses, and coaches) and students can provide a more complete understanding of bullying, which can in turn lead to the development of more effective prevention and intervention programs. This introductory chapter sets the stage by defining bullying, discussing prevalence rates, reviewing the research on gender and bullying, and identifying risk factors for bullying involvement. The association between bullying and well-being is also examined with attention to the physical health, mental health, and school outcomes that have been identified in the literature.

Definition and Forms of Bullying

Bullying can be defined as “a specific type of aggression in which (1) the behavior is intended to harm or disturb, (2) the behavior occurs repeatedly over time, and (3) there is an imbalance of power, with a more powerful person or group attacking a less powerful one” (Nansel et al., 2001, p. 2094). This widely agreed upon definition stems from the pioneering work of Dr. Daniel Olweus (1993) who identified intentionality, repetitive nature, and imbalance of power as three key features that differentiate bullying from other forms of aggression. These defining features of bullying are also evident in the definitions of bullying put forth by the American Psychological Association and the National Association of School Psychologists (Hymel & Swearer, 2015).

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) organized a panel to develop a uniform definition of bullying. This initiative stemmed from recognition of the importance of researchers and policymakers adopting a uniform definition of bullying to better understand prevalence rates and trends over time. The development of a uniform definition was also believed to be critical for guiding prevention and intervention efforts. The uniform definition outlined by the CDC panel described bullying as “any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm” (Gladden, Vivolo-Kantor, Hamburger, & Lumpkin, 2014, p. 7). This definition drew upon the three essential characteristics of bullying described in Olweus’ earlier and frequently cited work but made several, important distinctions between bullying and other forms of violence. First, the CDC definition distinguishes bullying from child maltreatment by noting that the behavior must occur between peers and does not include adult aggression directed toward children. Further, the CDC definition differentiates bullying from sibling violence by noting that the term bullying is not appropriate to describe conflict between siblings. An additional important distinction in the CDC definition is highlighting a separation between bullying and teen dating violence/intimate partner violence.

The definitions outlined above indicate that bullying behaviors are intended to inflict harm, but these definitions do not indicate specific types of behaviors in order to acknowledge that there are many different forms of bullying (Gladden et al., 2014). The most commonly identified forms of bullying are physical bullying, verbal bullying, property damage, social bullying, and cyber bullying. Physical bullying refers to use of force by the bully/bullies and includes behaviors such as hitting, kicking, or punching the victim. Verbal bullying refers to disdainful oral or written communication directed toward the victim and includes taunting, name-calling, and sending mean notes. Property damage refers to the bully/bullies taking or destroying the victim’s possessions (Gladden et al., 2014).

Social bullying is aimed at harming another’s social status or relationships (Underwood, 2003). Common examples of socially aggressive behavior include social exclusion, malicious gossip, and friendship manipulation. Relational bullying and indirect bullying are terms that have been used to refer to similar constructs. Of all the terms put forth, social bullying is the broadest by acknowledging aggressive behaviors that are verbal as well as nonverbal and direct as well as indirect in nature (Underwood, 2003).

Bullying others through electronic channels is a relatively new phenomenon, and many terms have been used to refer to this type of behavior including cyber bullying, electronic bullying, online harassment, Internet bullying, and online social cruelty (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009). The term cyber bullying is becoming widely adopted and has been defined as “willful and repeated harm inflicted through the use of computers, cell phones, and other electronic devices” (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009, p. 5). Researchers and educators are beginning to pay a great deal of attention to this type of behavior given the proliferation of mobile devices, which means cyber attacks can be shared with a large audience in a matter of minutes. Cyber bullying is also distinct from other forms of bullying in that victims may experience cyber bullying 24 hours a day, regardless of where they are. Thus, cyber bullying has the potential to be omnipresent, which may lead to increased feelings of vulnerability among victims. Cyber bullies may feel less inhibited than traditional bullies given that they can potentially remain anonymous through the use of pseudonyms and do not have face-to-face contact with their victims (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009).

Prevalence of Bullying and Victimization

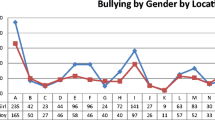

Nansel et al. (2001) conducted one of the most widely cited investigations into the prevalence of bullying behavior among U.S. youth. They drew upon a nationally representative sample of 15,686 students and focused on those reporting moderate or frequent involvement in bullying. Approximately 30% of students reported moderate to frequent involvement in bullying with 13% identified as bullies, 11% identified as victims, and 6% identified as bullies/victims. Males reported more frequent involvement in bullying than girls both as perpetrators and as victims; however, this is a more complex issue to which we return in the next section on gender and bullying.

Although the findings of Nansel and colleagues are frequently cited, it is important to note that there is wide variability in reported prevalence rates of bullying (Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Estimates of prevalence for bullying perpetration have ranged from 10% to 90% of youth, and estimates of prevalence for bullying victimization have ranged from 9% to 98% of youth (Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra, & Runions, 2014). There are a number of reasons that have been posed to explain this substantial variability in prevalence rates. Many suggest that these differences are likely a function of using different measurement tools (e.g., Hymel & Swearer, 2015; Modecki et al., 2014). Bullying victimization and perpetration have been assessed using parent, teacher, and peer reports as well as observational assessments; however, self-report remains the most common way to assess bullying involvement. Each reporter (e.g., teacher or student) provides a unique perspective, and thus there is often low to moderate correspondence between raters (Leff, Kupersmidt, Patterson, & Power, 1999). Important differences in measurement tools exist even when limiting focus to self-reports of bullying involvement; for example, some measures require participants to indicate whether they carried out or experienced specific forms of bullying behaviors (e.g., have you hit or shoved other kids, has anyone tried to turn people against you for revenge or exclusion; Rosen, Beron, & Underwood, 2013), whereas other measures ask participants the extent to which they have bullied others and have been bullied by others without differentiating forms of bullying behaviors. Sampling issues may also contribute to this variability with many researchers relying on community samples that are convenience-based and may differ in important ways such as gender composition (Hymel & Swearer, 2015; Modecki et al., 2014).

Given this wide variability, Modecki et al. (2014) conducted a meta-analysis to further examine bullying prevalence . This meta-analysis included 80 studies and examined traditional as well as cyber bullying. Drawing across the 80 studies, Modecki and colleagues found the mean prevalence rate of traditional bullying perpetration to be 35% and the mean prevalence rate of traditional bullying victimization to be 36%. The mean prevalence rates of cyber bullying perpetration and cyber victimization were considerably lower at 16% and 15%, respectively. Pulling across these 80 studies, there was a moderately strong degree of overlap between perpetration of traditional bullying and cyber bullying and victimization by traditional bullying and cyber bullying (mean correlations of 0.47 and 0.40, respectively). These results suggest that there is great similarity in youth’s behavior and vulnerability across online and offline settings. Interestingly, 33% of cyber victims believed the perpetrator was someone they considered to be a friend, and 28% believed the perpetrator was someone from school (Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). Based on these findings, it would appear that what happens in school spills over to cyber space and vice versa.

We now turn our attention to how bullying prevalence rates differ based on culture, grade level, and disability status. Researchers examining bullying prevalence rates across countries have found notable variability (Due et al., 2005); of the countries examined, the lowest levels of bullying were reported in Sweden with 5.1% of girls and 6.3% of boys reporting being bullied, and the highest levels of bullying were reported in Lithuania with 38.2% of girls and 41.4% of boys reporting being bullied. This variability in prevalence rates may be due to cultural differences in willingness to report bullying. Researchers and policymakers also ascribe this variability in prevalence rates to differing legislation; some countries like Sweden have strong laws in place to protect children in the school environment from bullying. Further analysis suggests that bullying may be more common in countries characterized by significant income inequality as this may lead to decreased sense of community and greater class competition (Elgar, Craig, Boyce, Morgan, &Vella-Zarb, 2009).

In addition, bullying prevalence rates may vary as a function of grade level. Bullying is believed to reach its peak in sixth grade (around 11 years of age) and then decrease. A report from the National Center for Education Statistics indicated that 24% of sixth graders reported being bullied, whereas only 7% of twelfth graders reported being bullied (DeVoe & Kaffenberger, 2005). The transition to middle school, which usually occurs at sixth grade, may be especially challenging. As students enter middle school, they may resort to bullying in an attempt to gain dominance in the social hierarchy; however, bullying may decrease over time as dominance hierarchies become more established. An alternative explanation is that older students may bully younger students, and there are fewer potential older bullies at higher grade levels.

Important differences in prevalence of bullying also exist between students in general and special education. Rose, Espelage, and Monda-Adams (2009) found the rate of bullying perpetration to be 10% for students without disabilities, 16% for students with disabilities in inclusive settings, and 21% for students with disabilities in self-contained settings. Similar differences were found for victimization with the rate of 12% for students without disabilities, 19% for students with disabilities in inclusive settings, and 22% for students with disabilities in self-contained settings. Bullying of students with a disability often takes the form of name-calling or mimicking aspects of the disability (Swearer, Espelage, Vaillancourt, & Hymel, 2010). Students with disabilities may be at increased risk for involvement in bullying as a result of limited social and communication skills (Rose, Simpson, & Moss, 2015). Those students with disabilities who are in an inclusive classroom setting may be less at risk as they may be more likely to develop their social skills by learning from their classmates without disabilities. Additionally, students with disabilities in inclusive settings may be more accepted and less likely to be subject to stereotypes than those in self-contained settings (Rose et al., 2009).

Gender and Bullying

Boys are often believed to be involved in bullying at higher rates than girls as both perpetrators and victims (Underwood & Rosen, 2011). As outlined in the previous section, Nansel et al. (2001) drew upon a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. youth and found that boys were more likely to report being both victims and perpetrators. Participants in this study were provided with a definition of bullying that did not differentiate between subtypes of bullying (i.e., “We say a student is BEING BULLIED when another student, or a group of students, say or do nasty and unpleasant things to him or her. It is also bullying when a student is teased repeatedly in a way he or she doesn’t like”, p. 2095) and were then asked to indicate whether they had bullied others or had been bullied by others. Many studies utilize similar measures that fail to differentiate between physical and social forms of bullying, and this may explain why boys are found to be both bullies and victims at higher rates than girls (Underwood & Rosen, 2011).

Gender differences seem to be contingent on the type of bullying examined. Boys are more physically aggressive than girls, and this appears to be a robust finding that is supported by a recent meta-analysis (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008). A number of reasons have been put forth to explain boys’ greater physical aggression including their typically stronger physique than girls. Parental socialization may also be an important contributor as parents may deem it more acceptable for boys to use physical aggression as they see them as more tough and dominant than girls (Rosen & Rubin, 2016).

Stereotypically girls and women are thought to be more socially aggressive than are boys and men. This is commonly reflected in media portrayals such as the film “Mean Girls” (Rosen & Rubin, 2015). The propensity to view social aggression as the realm of girls and women has been termed gender oversimplification of aggression (Swearer, 2008) and is evident as early as the preschool years. Giles and Heyman (2005) presented children with examples of socially aggressive behavior such as “I know a kid who told someone, ‘You can’t be my friend’ just to be mean to them” (p. 112). When asked to guess the gender of the perpetrator, both preschoolers and elementary school-aged children tended to infer that the socially aggressive character had been a girl. However, not all research has been consistent with this commonly held belief that females are more socially aggressive; although some studies have found girls are higher on social aggression, other studies have found no gender differences or even that boys are higher on social aggression (Rosen & Rubin, 2016). Drawing across 148 studies, Card et al. (2008) meta-analysis found girls were significantly higher on social aggression than were boys; however, this difference was so small that these researchers deemed it trivial.

Researchers have turned to examine gender differences in cyber bullying. Although cyber bullying behavior can be direct or indirect in nature (Chibbaro, 2007), many forms of cyber bullying resemble social aggression (e.g., spreading rumors online, posting content to embarrass a peer). Similar to investigations of social aggression, findings from research examining gender differences in cyber bullying have been mixed (Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, 2008; Hertz & David-Ferdon, 2008; Kowalski, Limber, & Agatston, 2008). Some studies have found that boys are involved in cyber bullying at higher rates than girls (Finkelhor, Mitchell, & Wolak, 2000; Mitchell, Finkelhor, & Wolak, 2003). However, the majority of the research suggests that girls are involved in cyber bullying at equivalent or greater rates than are boys (Hertz & David-Ferdon, 2008; Hinduja & Patchin, 2009; Kowalski et al., 2008; Lenhart, Madden, Macgill, & Smith, 2007; Williams & Guerra, 2007). Researchers are starting to note that girls and boys may engage in different types of cyber bullying behaviors (Underwood & Rosen, 2011). Boys’ online social cruelty may be more likely to take the form of calling others mean names online or hacking into another’s system. For girls, electronic aggression may be more likely to take the form of spreading rumors online.

Moving beyond mean differences in the rates of different forms of bullying, it is important to consider whether girls and boys play different roles in the bullying process. In the school setting, bullying is often a group process, in which students take different roles (Salmivalli, Lagerspetz, Björkqvist, Österman, & Kaukiainen, 1996). Boys are more likely to take the role of assistant than are girls, joining in on the bullying behavior in a role subordinate to the bully (e.g., may hold the victim). Likewise, boys are also more likely to serve as reinforcers, encouraging the bully through verbal comments or laughter. Conversely, girls are more likely to serve as defenders than are boys, supporting the victim and trying to intervene to stop the bullying. In addition to being defenders, girls are more likely than boys to take the role of outsider, remaining uninvolved and possibly trying to ignore the situation.

Risk Factors for Bullying Involvement

Given that negative adjustment outcomes accrue for both bullies and victims, a great deal of research has attempted to identify risk factors for bullying involvement. Being aware of this literature may help teachers and other school officials identify those who are at risk for bullying perpetration and victimization. There is low to moderate agreement between peer and teacher reports of bullying perpetration and victimization (Leff et al., 1999), and teachers and other school officials may fail to identify those students involved with bullying who do not pose immediate behavior management difficulties or fail to fit their preconceived notions of the typical bully or victim. Although we review the most commonly identified risk factors, it is important to realize that bullies and victims can display diverse profiles, and teachers and other school officials may overlook at-risk students who do not match commonly held stereotypes of the bully or victim (Rosen, Scott, & DeOrnellas, 2016).

There are a number of family factors that have been associated with aggressive behavior (Coyne et al., 2011; Griffin & Gross, 2004; Underwood, 2011). Being subject to harsh child rearing and disciplinary techniques coupled with little parental warmth may place youth at risk for aggressive behavior (Griffin & Gross, 2004). Researchers have hypothesized that parental hostility may be associated with lower child self-regulatory behaviors or that social modeling is occurring as children learn by observing how their parents treat them as well as others (Coyne et al., 2011). Interestingly, permissive parenting, which is characterized by high parental warmth and low parental demands and control, has also been identified as a risk factor for aggressive behavior (Underwood, 2011).

In addition to family factors, peer and media influences may place children at risk for aggressive behavior (Underwood, 2011). As there could be tendencies to associate with similar peers and nonaggressive peers may avoid them, aggressive children often affiliate with aggressive peers. Affiliation with deviant peers has been associated with greater antisocial behavior (Underwood, 2011). Just as association with violent peers is a risk factor, so too is consumption of violent media. Viewing violent television programs and films predicts both concurrent and future aggressive behavior (Coyne et al., 2011; Huesmann, Moise-Titus, Podolski, & Eron, 2003). Similar to social modeling that may take place within families, observational learning may occur with violent shows and movies, and children may imitate the behaviors displayed in the media they watch. Further, listening to songs with violent lyrics or playing violent video games may be associated with aggressive thoughts and behaviors (Anderson, Carnagey, & Eubanks, 2003; Anderson & Dill, 2000).

Although a number of external influences have been discussed, there are also temperamental and psychological risk factors for aggression. Bullies may be impulsive and lack self-regulatory skills (Carrera, DePalma, & Lameiras, 2011; Griffin & Gross, 2004). Further, bullies may display a lack of guilt or empathy (Carrera et al., 2011; Griffin & Gross, 2004). Researchers have suggested that bullies may have low self-esteem, but this association is supported by only some studies (Griffin & Gross, 2004).

Bullies are often believed to lack social skills; however, some children use aggression to gain social status (Coyne et al., 2011; Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Some aggressive children may possess peer-valued characteristics (e.g., attractiveness, humor) that moderate the association between aggression and popularity. Although these youth may be disliked by peers, they may still be seen as popular. Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, and Van Acker (2006) proposed four categories of students: popular-aggressive, popular-nonaggressive, nonpopular-aggressive, and nonpopular-nonaggresive. Popular-aggressive students may go undetected as teachers and other school officials overlook them (Hymel & Swearer, 2015).

Just as a number of risk factors have been identified for bullying perpetration, there are many factors believed to put youth at risk for victimization . Some victims may be viewed as passive and display submissive behavior and low self-esteem (Griffin & Gross, 2004; Schwartz, Dodge, & Coie, 1993). Conversely, some victims may be considered provocative as aggressive behavior is also a risk factor for victimization (Griffin & Gross, 2004; Hanish& Guerra, 2000).

A number of temperamental and social risk factors have been identified for victimization. Those youth who are victimized may be highly sensitive and lack regulatory skills, which in turn is associated with easily displaying their emotions (Carrera et al., 2011; Herts, McLaughlin, & Hatzenbuehler, 2012). In addition, victims are often socially isolated; they may lack strong friendships (Hodges, Malone, & Perry, 1997) and may have low-quality relationships with their parents (Beran & Violato, 2004).

Furthermore, appearance-based risk factors for victimization have been identified. Youth who are physically weak may be at increased risk for victimization (Hodges & Perry, 1999). Children and adolescents who are overweight are more likely to be victimized than their counterparts who are of average weight (Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Faibisch, 1998). Low ratings of facial attractiveness have also been associated with increased victimization (Rosen, Underwood, & Beron, 2011). However, the findings have been mixed as to whether craniofacial anomalies are a risk factor for victimization (Carroll & Shute, 2005; Shavel-Jessop, Shearer, McDowell, & Hearst, 2012).

Associations with Adjustment

Both bullying perpetration and victimization are associated with myriad forms of adjustment difficulties (Sigurdson, Wallander, & Sund, 2014). Children who are aggressive may have early difficulties regulating their emotions. These youth may be at risk for developing later adjustment problems that are associated with deficits in regulatory abilities (Underwood, Beron, & Rosen, 2011).

Aggressive behavior has been associated with internalizing problems as well as other forms of externalizing problems (Coyne et al., 2011; Underwood et al., 2011). Ratings of aggressive behavior predict internalizing problems including withdrawn depression, anxious depression, and somatic complaints (Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006; Underwood et al., 2011). Many explanations have been put forth to explain this relationship including that aggressive children may experience difficulties with peers and school that place them at increased risk for internalizing problems. Further, aggressive behavior may predict delinquency and rule-breaking behaviors (Coyne et al., 2011; Underwood et al., 2011). Students identified as bullies are rated higher on teacher ratings of conduct disorder (Smith, Polenik, Nakasita, & Jones, 2012). Aggressive children may be impulsive, which puts them at risk for these other forms of externalizing problems .

Additionally, aggressive students are at risk for academic and peer problems at school (Coyne et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2012). Bullying behavior is associated with lower academic achievement as well as poor school attendance (Feldman et al., 2014). Some researchers caution that some academic achievement measures, such as GPA, could possibly reflect behavioral difficulties and not solely academic ability. Moreover, bullying is associated with peer rejection in school (Coyne et al., 2011). Youth who bully others may be isolated, which in turn may lead to lower self-esteem (Smith et al., 2012); however, findings regarding the association between bullying and self-esteem have been mixed (Griffin & Gross, 2004).

Longitudinal work suggests that bullying involvement in adolescence can predict maladjustment in adulthood (Sigurdson et al., 2014). Being identified as a bully at ages 14 and 15 was associated with lower educational attainment and higher rates of unemployment at ages 26 and 27. Of those who were employed, bullying in adolescence predicted poorer quality relationships at work. Further, those identified as bullies in adolescence also used more tobacco and illegal drugs than non-involved youth. Researchers believe that these longitudinal associations suggest “a continuation of early problem behavior” (Sigurdson et al., 2014, p. 1614).

The association between victimization and negative adjustment outcomes is also well documented in the literature with longitudinal investigations finding that being bullied in childhood can predict maladjustment in adulthood (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). A great deal of concurrent and longitudinal research has shown that victimization experiences are linked to internalizing symptoms. Victimized youth report elevated levels of loneliness and social anxiety (Storch, Brassard, & Masia-Warner, 2003; Storch & Masia-Warner, 2004). Victims are also found to have lower self-esteem than their non-victimized counterparts (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). Furthermore, victimization is associated with increased risk for depression, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts (Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould, 2007).

Likewise, victimization is associated with externalizing problems. Victimization is associated with both physical and relational aggression (Sullivan, Farrell, & Kliewer, 2006). In addition, victimization experiences predict delinquency, substance use, and increased sexual activity (Gallup, O’Brien, White, & Wilson, 2009; Sullivan et al., 2006). Victimization may also be related to onset of sexual activity for girls; female college students who reported being frequently victimized across adolescence reported having had more sexual partners and engaging in first intercourse at an earlier age (Gallup et al., 2009).

Victimization experiences have been associated with physical health. Those who had been victimized have higher levels of somatic complaints (Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005). Two potential explanations were posed to account for this finding: the chronic stress of victimization could suppress the immune system leading to illness and victims may report being ill in order to miss school and escape their tormentors. In addition, the extant literature suggests that peer victimization is associated with poor quality sleep and disturbed eating patterns (Hatzinger et al., 2008; van den Berg, Wertheim, Thompson, & Paxton, 2002). Self-reported experiences of peer victimization are negatively related to sleep efficiency as assessed with electroencephalographic sleep profiles (Hatzinger et al., 2008). For adolescent girls, a history of teasing is positively related to body dissatisfaction and, in turn, eating disturbances (van den Berg et al., 2002).

Experts have called for additional research examining the relation between peer victimization and educational outcomes (Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & Toblin, 2005). Victimization is associated with poorer school adjustment outcomes including decreased school liking (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). Similarly, victimization is linked to lower GPA and standardized test scores in some studies (Schwartz et al., 2005). Experiencing bullying predicts school avoidance; some victims report missing school due to feeling unsafe (Hughes, Gaines, & Pryor, 2015).

Interestingly, not all bullied youth are affected to the same extent (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015). Some youth suffer more when faced with victimization whereas others appear to escape lasting maladjustment. These differing outcomes may be dependent on a number of risk and protective factors. Victimized youth seem to fare better when a large number of their classmates are bullied; given a sense of “shared plight”, victims may be less apt to blame themselves for their experiences of peer maltreatment and rather make attributions to external factors. Additionally, the extent to which victimization is chronic or fleeting may make an important difference. Youth experiencing incessant bullying demonstrate the worst adjustment outcomes (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Wardrop, 2001; Rosen et al., 2009). Social support may be a significant protective function, and this support can come from multiple sources including friends, family members, and teachers (McDougall & Vaillancourt, 2015).

Moving beyond focusing on bullies and victims, research has begun to examine the association between simply witnessing bullying and maladjustment. In a daily diary study, 42% of middle school students reported witnessing at least one incident of peer harassment at school (Nishina & Juvonen, 2005). These bystanders may be at risk just as bullies and victims are as findings suggest that witnessing bullying is associated with multiple forms of maladjustment including substance use, anxiety, somatic complaints, and depressive symptoms (Rivers, Poteat, Noret, & Ashurst, 2009). A number of theories have been put forth to explain this association between witnessing bullying and negative adjustment outcomes. Bystanders may experience maladjustment as they may worry that they could soon become victims themselves. In addition, bystanders may undergo “indirect covictimization through their empathic understanding of the suffering of the victim they observe” (Rivers et al., 2009, p. 220). Another possibility is that bystanders who do not intervene may experience extreme stress as they feel compelled to assist but do not do so (Rivers et al., 2009). Some have hypothesized that bystanders who themselves have been victimized at some point may be at greater risk for negative adjustment outcomes associated with witnessing bullying (Werth, Nickerson, Aloe, & Swearer, 2015).

Bullying in the School Context

The majority of bullying episodes take place in the school setting. It is reported that 82% of incidents of emotional bullying and 59% of peer assaults occur at school (Turner, Finkelhor, Hamby, Shattuck, & Ormrod, 2011). Students were asked to identify places where bullying frequently occurred; 18.9% reported bullying was often experienced in the class setting, and 30.2% reported bullying was often experienced in the cafeteria or at recess (Seals & Young, 2003). Even if bullying takes place off school premises, there is often spillover to the school environment. For instance, teachers report that episodes of cyberbullying can influence what occurs in their classrooms (Rosen et al., 2016).

Scholars point to the importance of preventing bullying in schools as this is an issue of human rights (Smith, 2011). Students have the right not to be bullied, and school officials are devoting increasing efforts to address bullying on their campuses. Unfortunately, these bullying prevention efforts are not always effective (Espelage, 2013). Some researchers suggest that bullying can be best addressed by fostering a positive school climate stating that “bullying is most effectively prevented by the creation of an environment that nurtures and promotes prosocial and ethical norms and behaviors, more so than by simply targeting the eradication of bullying and related undesirable behaviors” (Cohen, Espelge, Twemlow, Berkowitz, & Comer, 2015, p. 7).

Given the importance of school climate, it is important to look more in depth at influencing factors. Researchers have posited that “school climate is based on patterns of people’s experience of school life and reflects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching, learning, leadership practices, and organizational structures” (Cohen et al., 2015, p. 8). Some schools are believed to foster a “culture of bullying” (Espelage, Low, & Jimerson, 2014, p. 234) in which aggressive behavior is common and unlikely to elicit a response from teachers and school officials. In fact, school staff at these schools often hold passive or dismissive attitudes toward student aggression, and failure to intervene can reinforce bullying as there are no consequences for this form of misbehavior.

Conversely, a positive school climate can reduce problematic behaviors such as bullying by enforcing norms of a safe environment and fostering strong relationships (Espelage et al., 2014). Konold et al. (2014) identified the two main components of school climate as disciplinary structure and support of students. Fair enforcement of rules and policies coupled with a sense of perceived support and respect create a balanced environment, which has been termed an authoritative school climate. In these environments, students believe that teachers and school staff care about them, yet are aware that they will receive appropriate punishment if they break school rules. This type of school environment is often characterized by lower rates of bullying, higher levels of school liking, and greater completion of academic work.

Fostering a positive school climate to best address bullying requires all key players in the school to come together. It is important to recognize that “school-based aggression is a reflection of the complex, nested ecologies that constitute a ‘schools’ culture’ and thus, is best understood through an ecological framework” (Espelage et al., 2014, p. 234). Too often researchers and policymakers limit their focus to only one perspective and by doing so are missing the utility of considering multiple perspectives. In fact, the failure to engage all key players in the school may be one of the main reasons that bullying prevention programs fail (Cohen et al., 2015). Programs that are school-wide and multidisciplinary are more likely to succeed (Swearer et al., 2010). When schools create teams to address bullying that draw across different professions, members are able to bring their unique expertise and have access to different resources, which in turn contributes to program success (Kub & Feldman, 2015).

Drawing on this work, the underlying premise of this book is that we can best understand and address bullying by considering multiple perspectives within the school. The second chapter examines bullying from the student point of view including that of the aggressor, victim, and bystander. Chapter 3 focuses on bullying from the teacher’s perspective and highlights effective interventions for teachers to use in handling bullying in their classrooms. Chapter 4 addresses bullying from the perspectives of principals and school resource officers and discusses ways in which the two can effectively work together in order to best prevent and intervene in different forms of bullying. Chapter 5 describes the roles of school psychologists and school counselors in planning and implementing bullying prevention programs and their effect on schools. Chapter 6 explains how school nurses are important as members of teams to prevent and address bullying in schools. Chapter 7 incorporates the perspective of coaches and offers examples of bullying activities that occur in athletics and positive steps coaches may take to encourage athletes’ success and growth in lieu of bullying. The eighth and final chapter integrates the different perspectives of key school staff and provides common themes. Based on the recommendations provided in each of the chapters, we discuss possible school-wide bullying prevention and intervention efforts. In so doing, we highlight the importance of whole school programs and offer recommendations for how these programs can best be implemented by drawing upon resources across the school.

References

Anderson, C. A., Carnagey, N. L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 960–971. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.960.

Anderson, C. A., & Dill, K. E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 772–790. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.772.

Beran, T. N., & Violato, C. (2004). A model of childhood perceived peer harassment: Analyses of the Canadian national longitudinal survey of children and youth data. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 138, 129–147. doi:10.3200/JRLP.138.2.129-148.

Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. (2008). Enhancing child safety & online technologies: Final report of the Internet Safety Technical Task Force to the Multi-State Working Group on Social Networking of State Attorneys General of the United States. Retrieved from https://cyber.harvard.edu/sites/cyber.law.harvard.edu/%20files/ISTTF_Final_Report.pdf

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x.

Carrera, M. V., DePalma, R., & Lameiras, M. (2011). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of bullying in school settings. Educational Psychology Review, 23, 479–499. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9171-x.

Carroll, P., & Shute, R. (2005). School peer victimization of young people with craniofacial conditions: A comparative study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 10, 291–304. doi:10.1080/13548500500093753.

Chibbaro, J. S. (2007). School counselors and the cyberbully: Interventions and implications. Professional School Counseling, 11, 65–68. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-11.65.

Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., Berkowitz, M., Twemlow, S., & Comer, J. (2015). Rethinking effective bully and violence prevention efforts: Promoting healthy school climates, positive youth development, and preventing bully-victim-bystander behavior. International Journal of Violence and Schools, 15, 2–40.

Coyne, S. M., Nelson, D. A., & Underwood, M. K. (2011). Aggression in childhood. In P. K. Smith & C. H. Hart (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of childhood social development (pp. 491–509). West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Werner, N. E. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children’s social-psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 131–142. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-9009-4.

DeVoe, J. F., & Kaffenberger, S. (2005). Student reports of bullying: Results from the 2001 school crime supplement to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCES 2005–310). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Due, P., Holstein, B. E., Lynch, J., Diderichsen, F., Gabhain, S. N., Scheidt, P., & Currie, C. (2005). Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: International comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 15, 128–132. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cki105.

Elgar, F. J., Craig, W., Boyce, W., Morgan, A., & Vella-Zarb, R. (2009). Income inequality and school bullying: Multilevel study of adolescents in 37 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 351–359. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.004.

Espelage, D. L. (2013). Why are bully prevention programs failing in U.S. schools? Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 10, 121–123. doi:10.1080/15505170.2013.849629.

Espelage, D. L., Low, S. K., & Jimerson, S. R. (2014). Understanding school climate, aggression, peer victimization, and bully perpetration: Contemporary science, practice, and policy. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 233–237. doi:10.1037/spq0000090.

Feldman, M. A., Ojanen, T., Gesten, E. L., Smith-Schrandt, H., Brannick, M., Totura, C. M. W., … Brown, K. (2014). The effects of middle school bullying and victimization on adjustment through high school: Growth modeling of achievement, school attendance, and disciplinary trajectories. Psychology in the Schools, 51, 1046–1062.

Finkelhor, D., Mitchell, K. J., & Wolak, J. (2000). Online victimization: A report on the nation’s youth. Retrieved from http://www.missingkids.com/en_US/publications/NC62.pdf

Gallup, A. C., O’Brien, D. T., White, D. D., & Wilson, D. S. (2009). Peer victimization in adolescence has different effects on the sexual behavior of male and female college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 611–615. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.12.018.

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education.

Giles, J. W., & Heyman, G. D. (2005). Young children’s beliefs about the relationship between gender and aggressive behavior. Child Development, 76(1), 107–121. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00833.x.

Griffin, R. S., & Gross, A. M. (2004). Childhood bullying: Current empirical findings and future directions for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 379–400. doi:10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00033-8.

Hanish, L. D., & Guerra, N. G. (2000). Predictors of peer victimization among urban youth. Social Development, 9, 521–543. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00141.

Hatzinger, M., Brand, S., Perren, S., Stadelmann, S., von Wyl, A., von Klitzing, K., & Holsboer-Trachsler, E. (2008). Electroencephalographic sleep profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA)-activity in kindergarten children: Early indication of poor sleep quality associated with increased cortisol secretion. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42, 532–543. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.010.

Herts, K. L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2012). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking stress exposure to adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1111–1122. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9629-4.

Hertz, M. F., & David-Ferdon, C. (2008). Electronic media and youth violence: A CDC issue brief for educators and caregivers. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/%20pdf/EA-brief-a.pdf

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2009). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hodges, E. V. E., Malone, M. J., & Perry, D. G. (1997). Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology, 33, 1032–1039. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.1032.

Hodges, E. V. E., & Perry, D. G. (1999). Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 677–685. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.677.

Huesmann, L. R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C., & Eron, L. D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Developmental Psychology, 39, 201–221. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.201.

Hughes, M. R., Gaines, J. S., & Pryor, D. W. (2015). Staying away from school: Adolescents who miss school due to feeling unsafe. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 13, 270–290. doi:10.1177/1541204014538067.

Hymel, S., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70, 293–299. doi:10.1037/a0038928.

Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2007). Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 40–49. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18.

Kochenderfer, B. J., & Ladd, G. W. (1996). Peer victimization: Manifestations and relations to school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology, 34, 267–283. doi:10.1016/0022-4405(96)00015-5.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Wardrop, J. L. (2001). Chronicity and instability of children’s peer victimization experiences as predictors of loneliness and social satisfaction trajectories. Child Development, 72, 134–151. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00270.

Konold, T., Cornell, D., Huang, F., Meyer, P., Lacey, A., Nekvasil, E., … Shukla, K. (2014). Multilevel multi-informant structure of the authoritative school climate survey. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 238–255. doi:10.1037/spq0000062; 10.1037/spq0000062.supp.

Kowalski, R. M., Limber, S. P., & Agatston, P. W. (2008). Cyber bullying: Bullying in the digital age. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Kub, J., & Feldman, M. A. (2015). Bullying prevention: A call for collaborative efforts between school nurses and school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 658–671. doi:10.1002/pits.21853.

Leff, S. S., Kupersmidt, J. B., Patterson, C. J., & Power, T. J. (1999). Factors influencing teacher identification of peer bullies and victims. School Psychology Review, 28, 505–517.

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., Macgill, A. R., & Smith, A. (2007). Teens and social media (Pew Internet & American Life Project Report). Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org

McDougall, P., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Long-term adult outcomes of peer victimization in childhood and adolescence: Pathways to adjustment and maladjustment. American Psychologist, 70, 300–310. doi:10.1037/a0039174.

Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., & Wolak, J. (2003). Victimization of youths on the Internet. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 8, 1–39.

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 602–611. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100. doi:10.1001/jama.285.16.2094.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., & Faibisch, L. (1998). Perceived stigmatization among overweight African-American and Caucasian adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 23, 264–270. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00044-5.

Nishina, A., & Juvonen, J. (2005). Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development, 76, 435–450. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00855.x.

Nishina, A., Juvonen, J., & Witkow, M. R. (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 37–48. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_4.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Olweus, D. (1995). Bullying or peer abuse at school: Facts and interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 196–200. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772640.

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. M. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 479–491. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05.

Rivers, I., Poteat, V. P., Noret, N., & Ashurst, N. (2009). Observing bullying at school: The mental health implications of witness status. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 211–223. doi:10.1037/a0018164.

Rodkin, P. C., Farmer, T. W., Pearl, R., & Van Acker, R. (2006). They’re cool: Social status and peer group supports for aggressive boys and girls. Social Development, 15, 175–204. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00336.x.

Rose, C. A., Espelage, D. L., & Monda-Amaya, L. (2009). Bullying and victimisation rates among students in general and special education: A comparative analysis. Educational Psychology, 29, 761–776. doi:10.1080/01443410903254864.

Rose, C. A., Simpson, C. G., & Moss, A. (2015). The bullying dynamic: Prevalence of involvement among a large-scale sample of middle and high school youth with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 515–531. doi:10.1002/pits.21840.

Rosen, L. H., Beron, K. J., & Underwood, M. K. (2013). Assessing peer victimization across adolescence: Measurement invariance and developmental change. Psychological Assessment, 25, 1–11. doi:10.1037/a0028985.

Rosen, L. H., & Rubin, L. J. (2015). Beyond Mean Girls: Identifying and intervening in episodes of relational aggression. Teachers College Record, http:// www.tcrecord.org, ID Number 17959.

Rosen, L. H., &Rubin, L. J. (2016). Bullying. In N. Naples (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies,Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

Rosen, L. H., Scott, S., &DeOrnellas, K. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions of student aggression: A focus group approach. Journal of School Violence, 16(1), 119–139. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2015.1124340.

Rosen, L. H., Underwood, M. K., & Beron, K. J. (2011). Peer victimization as a mediator of the relation between facial attractiveness and internalizing problems. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57, 319–347. doi:10.1353/mpq.2011.0016.

Rosen, L. H., Underwood, M. K., Beron, K. J., Gentsch, J. K., Wharton, M. E., & Rahdar, A. (2009). Persistent versus periodic experiences of social victimization: Predictors of adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 693–704. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9311-7.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1993). The emergence of chronic peer victimization in boys’ play groups. Child Development, 64, 1755–1772. doi:10.2307/1131467.

Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Nakamoto, J., & Toblin, R. L. (2005). Victimization in the peer group and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 425–435. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.425.

Seals, D., & Young, J. (2003). Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence, 38, 735–747.

Shavel-Jessop, S., Shearer, J., McDowell, E., & Hearst, D. (2012). Managing teasing and bullying. In S. Berkowitz (Ed.), Cleft lip and palate (pp. 917–926). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30770-6_46.

Sigurdson, J. F., Wallander, J., & Sund, A. M. (2014). Is involvement in school bullying associated with general health and psychosocial adjustment outcomes in adulthood? Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1607–1617. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.001.

Smith, H., Polenik, K., Nakasita, S., & Jones, A. P. (2012). Profiling social, emotional and behavioural difficulties of children involved in direct and indirect bullying behaviours. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 17, 243–257. doi:10.1080/13632752.2012.704315.

Smith, P. K. (2011). Why interventions to reduce bullying and violence in schools may (or may not) succeed: Comments on this special section. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35, 419–423. doi:10.1177/0165025411407459.

Storch, E. A., Brassard, M. R., & Masia-Warner, C. (2003). The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescence. Child Study Journal, 33, 1–18.

Storch, E. A., & Masia-Warner, C. (2004). The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 351–362. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.003.

Sullivan, T. N., Farrell, A. D., & Kliewer, W. (2006). Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 119–137. doi:10.1017/S095457940606007X.

Swearer, S. M. (2008). Relational aggression: Not just a female issue. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 611–616. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2008.08.001.

Swearer, S. M., Espelage, D. L., Vaillancourt, T., & Hymel, S. (2010). What can be done about school bullying? Linking research to educational practice. Educational Researcher, 39, 38–47. doi:10.3102/0013189X09357622.

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S. L., Shattuck, A., & Ormrod, R. K. (2011). Specifying type and location of peer victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1052–1067. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9639-5.

Underwood, M. K. (2003). Social aggression among girls. New York: Guilford Press.

Underwood, M. K. (2011). Aggression. In M. K. Underwood & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social development (pp. 207–234). New York: Guilford.

Underwood, M. K., Beron, K. J., & Rosen, L. H. (2011). Joint trajectories for social and physical aggression as predictors of adolescent maladjustment: Internalizing symptoms, rule-breaking behaviors, and borderline and narcissistic personality features. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 659–678. doi:10.1017/S095457941100023X.

Underwood, M. K., & Rosen, L. H. (2011). Gender and bullying: Moving beyond mean differences to consider conceptions of bullying, processes by which bullying unfolds, and cyber bullying. In D. Espelage & S. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: An update (pp. 13–22). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

van den Berg, P., Wertheim, E. H., Thompson, J. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2002). Development of body image, eating disturbance, and general psychological functioning in adolescent females: A replication using covariance structure modeling in an Australian sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 46–51. doi:10.1002/eat.10030.

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 483–488. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002.

Werth, J. M., Nickerson, A. B., Aloe, A. M., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Bullying victimization and the social and emotional maladjustment of bystanders: A propensity score analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 53, 295–308. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2015.05.004.

Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2007). Prevalence and predictors of internet bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, 14–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rosen, L.H., Scott, S.R., DeOrnellas, K. (2017). An Overview of School Bullying. In: Rosen, L., DeOrnellas, K., Scott, S. (eds) Bullying in School. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59298-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59298-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-59892-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-59298-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)