Abstract

This chapter discusses the role of humour for political protest during the Gezi events in Turkey in the summer of 2013. By drawing on diverse theoretical references ranging from Freud to Virno, it argues that humour’s particular structure allows social movements to engage in the construction of political subjectivities alternative to what the norms of the given social order provide. Crucial to this is the self-critical dimension of humour, which is stressed by Freud’s later theory of humour as opposed to the joke or the comic. It helps to engender a process, in which protesters of diverse backgrounds or identities can recompose their mutual relationships.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

For a mainstream account of AKP’s shift to authoritarianism, see Özbudun (2014).

- 3.

These are the numbers of imprisoned army officials in February 2014: http://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/turkiye/37985/iste_cezaevindeki_TSK.html. (25 November 2016) in June 2014, most of the prisoners have been released after the Constitutional Court’s decision to grant a retrial.

- 4.

See the statements of Orhan Gazi Ertekin, co-chair of the Democratic Judiciary Association of Turkey, for a detailed account of the use of police and judiciary, http://birdirbir.org/orhan-gazi-ertekinin-kaleminden-duble-krizin-yapitaslari/, (25 November 2016) and of Ertuğrul Kürkçü, Honorary President of the Peoples’ Democracy Party (HDP) for the use of a ‘judiciary-police tutelage’ in the formation of the new regime, http://www.ertugrulkurkcu.org/haberler/akp-yargi-polis-vesayeti-altinda-baska-bir-rejim-olusturuyor/#.U6gT1CgVpSU (25 November 2016).

- 5.

For a detailed discussion of the millet system, see Braude and Bernard (1982).

- 6.

Alevism is an Anatolian cultural-religious practice, which locates itself within Islam, even though its non-conformist and heterodox rituals differ substantially from mainstream Sunni Islam. While it is not very easy to define Alevism due to its dynamic syncretism, which takes different forms in different parts of the Anatolian geography, its common and dominant feature can be said to be its humanist mysticism, which extends to equal treatment of men and women (Shankland, 2003). For centuries and up to today, Alevis have been perceived as heretics by mainstream Sunni Islam. Their heterodoxy, that is, their understanding and practice of religion—such as the use of dance and alcohol in religious ceremonies (Ayin-i Cem)—have made them a target of hostility of either the establishment or the Sunni Muslim majority. Although under secular republicanism, Alevis were not as isolated as they were at times of the Ottoman period, they still faced rejection, exclusion, and assimilation. Moreover, they also experienced attacks, threats, and were subjected to massacres (e.g. in Dersim 1938, in Maras 1978, in Corum 1980, and in Sivas 1993).

- 7.

A term used by Badiou in his book Rebirth of History (2012).

- 8.

For a visual account of this unexpected coming together, see the Gezi documentary of the Global Uprising collective, http://vimeo.com/71704435 (25 November 2016).

- 9.

For two accounts, which relate the forms and themes of the Gezi uprising with the local community struggles around urban and environmental commons, see Erensu, http://www.bianet.org/bianet/siyaset/147400-gezi-parki-direnisinin-ilhamini-yerelde-aramak and Evren, http://www.culanth.org/fieldsights/398-on-the-joy-and-melancholy-of-politics (25 November 2016). For an interpretation of Gezi as an urban uprising claiming the right to the city, see Kuymulu (2013).

- 10.

The planned shopping mall’s facade was a direct reference to Ottoman barracks at the very location of the park, which were demolished in the early 1940s as part of the Republican People’s Party’s strategy to secularize the urban environment. To ‘resurrect’ the barracks as a shopping mall was therefore also a symbolic gesture making reference to a combination of neoliberalism and Islamic authoritarianism. Against this background, ‘Resist Gezi’ served as an axis along which the reactions against urban renewal projects, privatizations, and forced enclosures of the commons, ecological destruction, and authoritarian/religious interventions into the (secular) private sphere were united.

- 11.

The government’s initially implicit, then increasingly explicit, hostility against Kemalism and Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) as a political personality who represents a republican-secularist revolution from above in accordance with a typically western modernization, is one of the reasons why Kemalism has been reinventing itself as a civilian-oppositional political position especially since 2007. This increasingly oppositional character is unusual in many ways as Kemalism, in its different forms, has been the official ideology of the Turkish state for many decades. The recent shift is characterized by the government’s decision to ban the popular demo-celebrations of October 29, Republic Day. The demonstration held on October 29, 2012 to celebrate the establishment of the Republic in 1923, was attacked by the police with pepper gas and water cannons, http://www.bbc.co.uk/turkce/haberler/2012/10/121029_republicans_last.shtml?MOB (25 November 2016). In response, more than one million people visited Anitkabir (the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal) in Ankara the following Republic Day in 2013, http://www.radikal.com.tr/yazarlar/eyup_can/ataturk_devlet_katindan_simdi_halka_indi-1160281 (25 November 2016). This can also be seen as a reaction to Erdoğan’s refusal to visit Anitkabir on national holidays. For a visual account of civilian Kemalism, that is, the Mustafa Kemal of the people and not the Mustafa Kemal of the state, see the photo album created by The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2013/nov/08/ataturk-turkey-photography-ersoy-emin#/?picture=421946213&index=0 (25 November 2016).

- 12.

One of the first decisions taken by the ‘Forums’, which were established after the Park was raided by mid-June, was precisely that of strengthening the principle of ‘civility’, not only in the sense of the non-military character of the fights in the streets, but also in the sense of a discursive, political ethic.

- 13.

http://www.iha.com.tr/asayis/israil-bayragi-yakmak-isteyen-guruba-tepki/279709 (25 November 2016).

- 14.

http://www.radikal.com.tr/turkiye/gezi_parkinda_kandilli_eylem-1136463 (25 November 2016).

- 15.

- 16.

However, when it comes to norms there is an important remark that needs to be made here. In a conventional sense, norms are a referential address of critique, as we are told by Jürgen Habermas, Axel Honneth, and others. In this sense, confronting reality with the given set of norms is the preferred strategy of social critique. Accordingly, many forms of humor reflect a model of critique that stands in the tradition of enlightenment. In the wake of the events of mid-December 2013, when leaked phone calls revealed the corruption and bigotry of the AKP establishment, a peculiar, nevertheless unsurprising reaction in many parts of society could be witnessed. People who support the government did not seem to be disturbed at all in the face of the evidence. A typical statement made by a taxi driver in Istanbul reads: ‘Maybe not every bidding procedure was correct, maybe he [Erdoğan] enriched himself, maybe he had an affair, but what counts is that he worked hard for our country. So we should grant him that. We will vote for him, as long as he wants to govern us’. So, in contrast to what many observers in western media suggest, the support for the AKP cannot be explained as the result of a mere lack of critical information—in the sense that the majority of the population has insufficient access to the internet or that most Turks don’t read newspapers, and so on. Where norms are the reference of critique, it is indeed paramount to understand their role in social interaction. As the taxi driver’s statement reveals, norms do not necessarily determine the value of behavior. This is also the reason why those forms of humor that rest on the existence or validity of norms have a rather limited impact. They can organize and mobilize the opposition, but will probably fail to interrupt the reasoning of the population that supports the establishment. The failure of irony has to do with the fact that it relies too much on the idea that norms have a monolithic and homogenous nature. In order to better understand the field of resonance produced by humorous interventions, and especially by irony, attention should be paid to the heterogeneity of norms, which can even be in conflict with one another, since norms, at least from a sociological viewpoint, are embedded in and derived from social practices.

Bibliography

Atasoy, Y. (2009). Islam’s marriage with neoliberalism: State transformation in Turkey. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and his world. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Badiou, A. (2012). The rebirth of history. London: Verso.

Balibar, E. (1998). Spinoza and politics. London/New York: Verso.

Bergson, H. (1911). Laughter: An essay on the meaning of the comic. London: Macmillan.

Braude, B., & Bernard, L. (1982). Christians and Jews in the Ottoman Empire: The functioning of a plural society. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers.

Coşar, S., & Yücesan-Özdemir, G. (2012). Silent violence: Neoliberalism, Islamist politics and the AKP years in Turkey. Ottowa: Red Quill Books.

Critchley, S. (2002). On humour. London: Routledge.

Davies, C. (2007). Humour and protest: Jokes under communism. International Review of Social History, Humour and Social Protest, 52, 291–305.

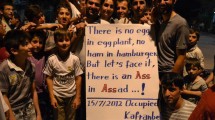

Della Ratta, D. (2012). Irony, satire, and humor in the battle for Syria. Muftah, [Online]. Available: http://muftah.org/irony-satire-and-humor-in-the-battle-for-syria/. Accessed 7 Nov 2014.

Eco, U. (1986). Faith in fakes: Essays. London: Secker & Warburg.

Fominaya, C. (2007). The role of humour in the process of collective identity formation in autonomous social movement groups in contemporary Madrid. International Review of Social History, Humour and Social Protest, 52, 243–258.

Freud, S. (1961). Humour (1927). In S. Freud, The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 21: 1927–1931. London: Hogarth Press.

Hiller, H. (1983). Humor and hostility: A neglected aspect of social movements analysis. Qualitative Sociology, 6, 255–265.

Insel, A. (2003). The AKP and normalizing democracy in Turkey. South Atlantic Quarterly, 102(2/3), 293–308.

Iskander, A. (2013). Egypt in flux: Essays on an unfinished revolution. Cairo/New York: The American University in Cairo Press.

Kuymulu, M. B. (2013). Reclaiming the right to the city: Reflections on the urban uprisings in Turkey. City, 17(3), 274–278.

Melucci, A. (1996). The process of collective identity. In H. Johnston & B. Klandermans (Eds.), Social movements and culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Özbudun, E. (2014). AKP at the crossroads: Erdoğan’s majoritarian drift. South European Society and Politics, 19(2), 155–167.

Rancière, J. (1995). On the shores of politics. London/New York: Verso.

Shankland, D. (2003). The Alevis in Turkey: The emergence of a Secular Islamic tradition. London: Routledge Curzon.

Spinoza, B. (2000). Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Teune, S. (2007). Humour as a guerrilla tactic: The West German student movement’s mockery of the establishment. International Review of Social History, Humour and Social Protest, 52, 115–132.

Toprak, B. (2009). Being different in Turkey: Religion, conservatism and otherization: Research report on neighborhood pressure. Istanbul: Boğaziçi University.

Virno, P. (2007). Multitude between innovation and negation. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Yeşilada, B., & Rubin, B. (2011). Islamization of Turkey under the AKP rule. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Karakayali, S., Yaka, Ö. (2016). Humor, Revolt, and Subjectivity. In: Oberprantacher, A., Siclodi, A. (eds) Subjectivation in Political Theory and Contemporary Practices. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51659-6_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51659-6_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-51658-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-51659-6

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)