Abstract

This introduction explores the potential functions that political humor might serve, as a mode of resistance or a “tiny revolution” or way of telling the truth, but also ultimately often reinforcing the position and dominance of those already in power. It then looks at how the subsequent chapters in the book trace an alternative history of twentieth-century China through the “technology” of various forms of political humor.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

As 2014 ended and 2015 began, humor was indeed political in the most geopolitical, “high politics,” of senses. In November, the release was delayed of the American satirical film The Interview, about an assassination attempt on North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un, when its studio, Sony Pictures, was the victim of a hacking attack. The attack led to the release of private emails and other sensitive information about celebrities and was later linked to North Korea, which earlier had called the film an “act of terrorism” and promised “merciless retaliation” for it. Figures in Hollywood subsequently critiqued Sony as “caving” to “cowardice” by initially refusing to release the film; it was later released as well as viewed illegally online millions of times (“The Interview: A Guide to the Cyber Attack on Hollywood” 2016).

Then, on 7 January 2015, the offices of Parisian satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo were attacked by gunmen affiliated with the terrorist group Al-Qaeda in Yemen, killing 12 and injuring several others. The radicalized pair of brothers who committed the attack targeted Charlie Hebdo, a publication with a long history of irreverent secularism, because it published satirical images of the Prophet Mohammed; Al-Qaeda in Yemen subsequently claimed responsibility for the attack as “vengeance for the messenger of Allah” (Reuters 2015). Both The Interview and Charlie Hebdo were cases of Western cultural outlets using satire to mock monolithic ideological claims, either totalitarian or fundamentalist, which are closed to the possibility of discursive diversity or multiplicity. The response to this satire was punishment through transnational, violent terrorism and cyberwarfare.

As the North Korean case was unfolding, within China the Xi Jinping regime, as part of its generally increasing control of public discourse and civil society, was also seeking to exert control over the deployment of humor and satire as political weapons. As various chapters in this book examine, increased personal and social freedom in the reform era, combined with the creativity and range of expression offered by the internet, led to a wide emergence of politically-directed humor that had been suppressed during the earnestness of the Mao period (see Moser 2004; Abrahamsen 2011). This flowering of online satire, rooted in both traditional and longstanding Chinese linguistic idioms as well as novel modes of expression, led to the regime’s State Administration for Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television, seeking to ban “wordplay,” promoting only standard usage and noting that “Idioms are one of the great features of the Chinese language and contain profound cultural heritage and historical resources and great aesthetic, ideological and moral values” (Branigan 2014). While less overtly imbued with geopolitical significance and violence, this case also features efforts to suppress the use of humor in defining the proper and acceptable contours of public discourse, even in the internet era, seeking to contain the emergence of internet satire through hegemonic notions of how language can and should be used.

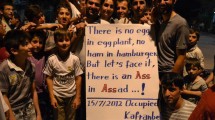

All of these cases demonstrate the impact humor can have on real-life politics. Those who come under its attack seek to bring it under control, resorting to measures not excluding the legislating process, intimidation and violent retaliation. Those who exploit it to their advantage, on the other hand, often use it as a tool to expose the mendacity and pomposity of the political entities with which they have to contend. These two camps—those who laugh and those who are laughed at—stand in opposition to each other. The history of modern China is filled with episodes representing the pull and push between them, on which the chapters of this volume will hopefully shed light.

We have thus far deliberately refrained from describing the contention between these two forces in a vertically hierarchical way. The examples of the American film The Interview and the Paris incident of Charlie Hebdo alluded above clearly demonstrate that the joker and the butt of the joke exist in a much more complex power relationship. All too often, however, political humor is taken to be the weapon of the underdog, which they wield when all other channels of political expression are deprived of them. In this vein, Benton (1988) is thus able to assert that “a society with the vote has no urgent need of political jokes, for it has more effective way of easing political tensions”. Political jokes, he continues, are the symptom of the strain of life under dictatorship where “people’s public faces no longer match their private feelings” and the discrepancies and confrontations between private feelings and the public life provide “the ingredients for an excellent humor.” In a similar way, George Orwell (1970) argues that “every joke is a tiny revolution.” Even though it may not instigate an actual uprising, it upsets the established order by making those in power look ridiculous.

Yet, it is by no means easy to gauge the effect of political humor, even if it succeeds in eliciting the kind of laughter or ire it intends. Even Benton maintains that political jokes are revolution only metaphorically and their victories are “moral” rather than “material” (1988), while Orwell (1970) concedes that jokes are merely “temporary rebellion.” The fact remains that the shrewd authorities that are being laughed at can always ride out the storm by refusing to be baited. By choosing not to take offence at the humor directed at them, they can patiently wait for the joke to die down on its own accord. Time is on the side of the status quo, for ultimately, humor is the best way of dissipating rather than heightening tension. Political humor captures and capitalizes on the dissatisfaction of society, but by articulating feelings of seething hostilities, it end up reducing them. It is with good reason that Link and Zhou (2002) describe humor of this kind as a safety valve.

More importantly, it is questionable that political humor necessarily serves the disenfranchised. Bergson (1911) points out that laughter is indiscriminate in its attack: “It has no time to look where it hits,” and like diseases, “strike[s] down some who are innocent and spare[s] some who are guilty,” while it can be used to express subversive views, it comes just as likely to rally behind the dominant, the mainstream and the powerful. The ethnic and gender jokes prevalent in all cultures, for example, poke fun at the deviant, the disabled and the disprivileged, and show all too clearly that humor can be conservative in spirit (Wilson 1979). If only in an indirect way, it can be used to reinforce the existing ideology and mores. In this sense, humor is a double-edged sword that cuts both ways. It can be said to have no agenda (Benton 1988) and can be summoned to use by any political stance and persuasion. In fact, as some chapters of this volume shows, it can be initiated from above, albeit, to be sure, with unforeseen results in some cases.

Even when political humor is put to the aid of the downtrodden, frivolity, supposedly its very strength, may well become one of its weakness. As it flits across the surface of political absurdity, catching elements that lend themselves most easily to the making of laughter, it must sacrifice depth of analysis, unless the humor takes the form of sustained satire beyond an isolated work of cartoon or a brief scathing internet joke. As such, humor provides moments of hilarity but rarely offers systematic programs of actions. Worse, it can justifiably be argued that its lack of seriousness might end up trivializing and normalizing the worst kind of political excesses and improprieties, and taking away the very drive and reason for political action.

It would seem, therefore, a thorough understanding of political humor has to begin with the recognition that it can be but is not necessarily a tool of resistance. It can be but is not necessarily aimed at those in power. Each manifestation can be a tiny revolution, but there is no guarantee that the revolution will have any long-lasting effect. It can express but does not necessarily sway political opinions, or at least, not necessarily in the way it intends.

If political humor as described above sounds an ineffectual or unpredictable way of accomplishing concrete political goals, one must bear in the mind the seductiveness of humor. The Chinese saying that was once used to describe the cautionary functions of the folk songs in Book of Songs—“The singer will be free from censure, while the listener will have a chance to heed to the wisdom of the words of the song”—may well apply to political humor. Freud (1985) speaks of the joke’s characteristics of “drawing the laughers over to one’s side,” disarming or bribing the hearer by the pleasure it offers. To be sure, there is aggressiveness in political humor, but the fact that it is delivered under the veil of humor makes it possible for the hearer to temporarily let down his guard. Whether the humorist will escape censure or punishment depends in the end on the reaction of the listener, but it seems incontrovertible that political humor provides a relatively safe avenue for the humorist to get around external restrictions and touch on issues that are considered taboo.

Ultimately, the impact of political humor is cumulative. One does not expect a single political joke to pivot the public opinion, to win or lose an election or to raise or bring down a regime. Rather, humor works in subtle and persistent ways. Many (Link and Zhou 2002; Liu 2012; Luke 1985) have pointed out the corrosive effect of political humor, where by degrees, it exposes the pride and pretensions of its opponent and cuts it down to size. Liu (2012), in particular, alludes to the need to tell truth in addition to make jokes, for jokes on their own can do very little to change reality.

1.1 Political Humor in China’s Turbulent Twentieth Century

The chapters in this volume trace the abundant ways that political humor points to limitations in the state’s abilities to monopolize discourses regarding China’s paths toward modernity in the twentieth and early twentieth-first centuries. During this period, the continually politicized nature of China’s road from trauma to triumph, semi-colonialism to major world power status, also meant that even mundane, daily life has often taken on a political significance. These papers demonstrate various ways that humor indicates intersections and interactions of popular sentiments and official positions, charting a sort of alternative history of modern China, from late Qing uncertainties regarding political reform, to the warfare characterizing much of the post-imperial period, into the hopes of the early post-“liberation” 1950s. Then, the post-Cultural Revolution openings created new spaces and topics for humor on the mainland, as did the contradictions of reform and new technologies of communication, while in the same period Hong Kong’s political transitions and uncertainties also provided fodder for politicized humor in popular culture as well as the political process itself.

The papers here thus chronicle a wide set of mediums for humor, including the relative freedom of political cartooning, the contextual and cultural adaptations of xiangsheng and standup comedy, the existence of subtle critical spaces in film, the milder use of humor in political campaigns, and the often barbed manifestations of satire in the anonymity of the internet. Humor itself is a technology of expression, one that can be employed in different settings for differing purposes. China’s process of constructing a modern-nation state led to the emergence of new forms of identity and political community, and shared experiences as well as their disjunctures contribute to hopes and disappointments in popular consciousness—as Richard Rorty writes, “common vocabularies and common hopes” both “bind societies together” and also provide the grounds for irony due to alienation from these hopes (Rorty 1989). In the circumstances of China’s twentieth century, political humor often expresses the “incongruity” between expectations and realities; as John Morreall notes, “Schopenhauer explained the incongruity behind laughter as a mismatch between our concepts and the real things that are supposed to be instantiations of these concepts” (1987). The sheer seriousness of China’s political challenges themselves have contributed to an earnest and “solemn public atmosphere” (Liu 2012), but also the creation of plentiful opportunities for “mismatches” between solemn claims and their implementation. These factors, combined with China’s openings to the outside world and the development of new concepts of mass political participation and even democracy, led at certain moments to the flowering of imaginative truth-telling as well as moments of the state itself seeing to harness that imaginative potential for its own purposes. Thus, political humor sometimes becomes politicized humor, and its potential to challenge power relations instead becomes a mode of maintaining them.

1.1.1 Humor in China’s Transitions Toward Socialism

I-Wei Wu, in “Illustrating Humor: Political Cartoons in Late Qing Constitutionalism,” points to the surfacing of political humor in the political ruptures at the beginning of the twentieth century, a moment of political opening that allowed for nods both to the use of political humor in the Chinese tradition as well as its usage in debates regarding China’s political future. Wu situates the cartoons he is examining in the long history of humor being used for political purposes in the Chinese tradition, but also in the novel form of newspaper journalism introduced from the West, and examines the ways that they satirized and thus offered commentary on the fervent debates regarding constitutionalism occurring in China in the last years of the dynastic rule. Tracing the genealogies of the emergence of pictorial humor in modern China, Wu offers a lexicographical account of Chinese terminologies for the sorts of images that might be placed generically under the term “political cartoon,” and in this genealogy also presents the ways that these pictures offer both “historical record and comical relief through exposing the absurdity at the core of political issues.” Analyzing cartoons published in The National Herald from 1907 to 1911, Wu then looks at how various pictorial depictions of the constitutionalist debates in this period made fun of officials as well as reform advocates as being ineffectual both due to personal failings and persistent Qing despotism, thus using incongruity to point out the innate contradictions of these reform efforts. It is perhaps not surprising that such humor emerged in discussions about constitutional government and its corresponding expanded concepts of citizenship, for the contemporary philospher and dissident Hu Ping writes that “By making fun of power, people claim their sense of equality” (Hu 2013). Wu also analyzes the uproar over a 1911 cartoon that satirized the Consultative Council to show the political efficacy that cartoons in this period could have to substantively critique government officials.

Humor emerged more and more as a vehicle of political expression in the Republican era; in the 1930s, Lin Yutang wrote of its potential to check the “excesses of corrupt government and overweening local officials” (Chey 2011). These themes can be found in the cartoons of Zhang Leping, whose pieces on the Second Sino-Japanese War are discussed by Laura Pozzi in “Humor, War, and Politics in San Mao Joins the Army: A Comparison Between the Comic Strips (1946) and the Film (1992).” Like Wu, Pozzi situates her discussion of the Zhang Leping comics and the later PRC film adaptation in their respective socio-political contexts, with the 1946 moment of civil war actually offering some space for a mode of a “nuanced and multilayered version of the War of Resistance” for Zhang Leping in his depiction of San Mao. A mere young child, San Mao patriotically signs up to fight the Japanese but in his service exposes the vices not only of the Japanese enemy as had been the target of wartime propaganda cartoons intended to empower Chinese fighters, but also of the selfish laziness of the Chinese soldiers and the abuses of power of the Chinese officers. Ultimately for Zhang, the humorous way that he depicted these situations, as well as the absurdity inherent to the nature of San Mao as a child soldier, provided an entertaining way of depicting the devastation of China’s many years of conflict as well as an implicit critique of the ongoing war between the Guomindang and the Chinese Communist Party still ravaging the country in 1946. Following a period of being banned during the Mao era, these comics were reissued in the 1980s and followed by a much-changed film made in 1992, with San Mao in this case an unwilling soldier for the GMD whose officers were wholly blamed for the suffering of the Chinese people. Thus, the politically nuanced satire of the 1946 cartoons was politicized in the 1990s as CCP propaganda, with the critical potentiality and alternative imaginings of satire being replaced by more overt ridicule of the GMD and Japanese enemies of China.

This didactic potential in humor was an important part of its emergence in the early years of the People’s Republic of China’s film culture, as the country developed its own film industry but in dialogue especially with its state socialist brethren, as discussed by Xiaoning Lu in “Chinese Film Satire and Its Foreign Connections in the People’s Republic of China (1950–1957): Laughter Without Borders?” The Maoist dictum that art and literature should serve the workers made culture inherently political, and there remained tension between post-liberation desires for laughter and the Party’s fears of the disruptive potentials of comedy, but there remained space for cultural negotiation in both film production and audience reception, especially in the early Mao years. The introduction of Soviet-bloc films into China in the early 1950s included comedies that satirized both the corruption of the old regimes as well as some of the humorous aspects of life under socialism. Lu examines the Soviet film Did We Meet Somewhere Before? and the Lü Ban Chinese remake The Man Who Doesn’t Bother About Trifles to show how they used depictions of daily life to in the former case offer critical observations of Soviet society while in the latter to primarily satirize an intellectual, “the only uncontroversial object of satire in the early PRC.” These two films were thus rooted in transnational socialist “consciousness of shared temporality and unbounded connectedness with absent ‘others’ propelled by common ideology and culture,” but diverged in their political settings, with the Soviet film emerging during the Khrushchev Thaw and the Chinese version constrained to be “edifying” and “de-politicized” by notions of what constituted “appropriate laughter” in the early PRC. The “imagined community” of the nation-state formed through shared consumption of popular culture, including humor (Gong and Yang 2010) can be both expanded beyond and constrained by national borders.

1.1.2 Joking in the PRC

The emergence of the reform era led to a greater potentiality for humor to be used as a form of individual expression and even empowerment (Davis 2013) even as new technology provided the potential for its wider dissemination as discussed by a number of observers of the e’gao (“spoofing”) internet phenomenon (Gong and Xin 2010; Hu 2013; Liu 2012; Rea 2013). David Moser traces the adaptations of xiangsheng through the early twentieth century and especially in the PRC through the present day in “Keeping the Ci in Fengci: A Brief History of the Chinese Verbal art of Xiangsheng”. Moser notes that pre-liberation xiangsheng had its origins as street theater that had to compete for audiences and often satirized newsworthy topics including “corrupt officials, social elites, country bumpkins, the handicapped, prostitutes, pompous scholars, and even political leaders” in a “subversive puncturing of pretense and hypocrisy”. This “anti-authoritarian quality” made it a target for post-1949 Party interventions both due to and despite its character as folk art and potential educational usages. Leading xiangsheng stars were co-opted by the Chinese Communist Party to create propaganda satirizing and critiquing America, but such didactic xiangsheng lost their satirical bite and thus their humorous appeal. One xiangsheng piece of the period, “Buying Monkeys”, appealed to audiences but also seemed to critique socialism and was criticized by the CCP, and much xiangsheng under Mao was thus politicized and sanitized. The end of the Mao era created an opening for “cathartic” laughter as Jiang Qing and the Gang of Four became potential but also brief-lived targets for xiangsheng satirical treatments. The social openings in the 1980s allowed for some xiangsheng artists to create works that operated on multiple levels of meaning, and so to embed implicit political critiques of, for instance, the moral emptiness of the era, into their performances. Meanwhile, the internet’s emergence allowed for some new xiangsheng stars to emerge who were able to joke about corruption and social problems in vulgar ways and were critiqued by the Party more for the latter than the former aspects of their humor.

Before the spread of the internet in China, but after the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, the 1990s combination of rampant commodification of culture combined with continued censorship of any arts featuring social or political content led to likely xiangsheng jokes being co-opted in underground forms of joke-based humor, discussed by Howard Choy in his study, “Laughable Leaders: A Study of Political Jokes in Mainland China”. The bawdiness of xiangsheng is also an important component of much of the post-Mao humor depicted by Choy, who claims that political joking “demystifies the solemnity of politics as the dominant discourse” and, like xiangsheng in its early forms, is ultimately “anti-authoritarian” in its public, opinion-based affect, while also questioning the actual political efficacy of such forms of expression. Like xiangsheng, the first post-Mao emergences of political humor were collections of jokes mocking the farcical qualities of the Cultural Revolution, though these only targeted allowable figures and rarely the Chairman himself. Later as reform took hold in China, a culture of private joking as well as occasional public performances by comics such as Zhou Libo emerged that targeted the incompetence and stupidity of certain high leaders, as well as sometimes featured sexual themes. Sometimes these more recent jokes were merely Chinese versions of satiric treatments of other foreign leaders, so Chinese humor continued as part also of the global, cynical imaginary that finds reason to satirize all sorts of utopian claims.

Choy ultimately finds that the laughter provoked by these sorts of jokes “functions as a lubricant, which helps prevent political conflicts and maintain social stability”, though they can also “engender critical consciousness”. This ambivalence is consistent with wider literatures on cynicism and political humor, with some finding cynicism to be an “a political rejection of politics” (Tao 2007) and others finding it containing the potential to be “probing and illuminating” (Bennett 2007). Le Ping and Sharon Wesoky assert that the former is more the case for gendered internet humor in “The Politics of Cynicism and Neoliberal Hegemony: Representations of Gender in Chinese Internet Humor”. Using jokes about gender relations found on the Chinese internet, they examine these as examples of the “depoliticization” of Chinese society even as they also feature commentary on society and politics. Briefly tracing the emergence of humor on the Chinese internet among tensions between freedom and control and thus finding it to be containing “multivalent” potentialities, Wesoky and Le ultimately locate internet humor as part the neoliberal realm of “depoliticized politics” discussed by New Left critic Wang Hui, an expression of cynicism and political passivity. The gendered jokes, about marital relations and the proper role of women, serve an ironically didactic function in a China where moral meaning has become individualized and privatized, and yet they also have political implications in their implicit rejections of Maoist feminism’s radical gender equality and their emphasis on women’s returning to more traditional roles as well as needing to commodify themselves in a corrupt and market-oriented society. Many of the jokes, thus, are implicitly criticizing post-Mao moral degeneration and revealing socio-political anxieties even as they primarily manifest “privatized despair.”

1.1.3 The “Special Amusing Region”: Humor in Hong Kong

Turning to Hong Kong, the three final chapters examine humor in the “Special Administrative Region” both before and after the transition to Chinese rule in 1997. The case of Hong Kong is one where “historical contingency” has been a “comic muse” (Rea and Volland 2008), perhaps even more so than on the mainland. King-fai Tam, in “Political Jokes, Caricatures, and Satire in Wong Tze-wah’s Standup Comedy”, in the end agrees with Choy that political humor serves primarily as a “safety valve” rather than as a creator of viable and functioning political opposition. Focusing on Hong Kong prior to the end of British rule, Tam examines the ways that cultural openness combined with “stalled politics” to create a fertile ground for political satire, especially in the Cantonese standup scene. While originating as an import from the West, Cantonese-language standup comedy in Hong Kong emerged as a much more overtly political medium than its English version in the territory. Focusing on star Wong Tze-wah, whose shows are massive productions that create the atmosphere of a “communal event” due to Wong’s use of audience participation, Tam looks at how his shows, especially those before 1997, were also “overtly and aggressively political”. While the political force of his satire existed partially through his skill at caricatures of public figures that necessitate the existence of a “common vocabulary” to create the grounds for humor, Wong also employs Hong Kong’s strong economic identity as well as its historical background to assess its 1990s “political malaise”. This approach allows him to combine political, economic, and social satire in his long-form comedic shows, which add up to “fully realized satire”.

The evolution of Hong Kong citizens’ political consciousness is the subject in a different way of the examination of Foong Ha Yap, Ariel Shuk-ling Chan, and Brian Lap-ming Wai at the direct political deployment of humorous rhetoric in “Constructing Political Identities Through Characterization Metaphor, Humor, and Sarcasm: An Analysis of the 2012 Legislative Council Election Debates in Hong Kong.” Using methods from linguistics, Yap, Chan, and Wai scrutinize the quite literal politicization of humor as it is used in electoral strategies by politicians seeking to gain the favor of voters. In the case of the increasing aggressiveness of Hong Kong’s political discourse as some in the territory seek a more democratic political identity even as it is increasingly tied to Beijing, politicians especially employ metaphors, often humorous ones, as verbal indirectness strategies to create diverging political identities for themselves and their opponents. In their analysis of the 2012 Legco debates, the authors find that these metaphors featured references to opponent politicians’ cushy relations with Beijing as well as the financial burdens faced by Hong Kong residents as ways of reaching the public and making one’s own political party seem more appealing to voters.

Finally, Karen Fang provides a look at the sensibilities of a prominent creator of (sometimes) politically-oriented humor, in “‘Absurdity of Life’: An Interview with Michael Hui.” Hui, a star of Hong Kong film especially in the 1970s and 1980s, was also a screenwriter and director as well as a partial owner of his studio, Golden Harvest. His characterizations in his films were often humorous depictions of the “relentless capitalism” characterizing Hong Kong, though, as Tam discusses the import of standup comedy into Hong Kong from the West, Michael Hui’s films were an important Hong Kong cultural export, thus showing the “universal quality of his humor and social satire”. He notes in the interview that he seeks to depict the “absurdity of life” and that all the inspirations for his stories come from life. He was partially interested in owning his production studio, starting in the 1970s, to give him more creative freedom, but both this freedom and the prosperity of the Hong Kong film industry declined after the territory returned to Chinese control in 1997, an indication of the resolutely political contexts of filmic humor, with films needing to “not offend the Chinese government”. Hui notes that this change means that “Things are not as funny anymore…There are things you can’t say anymore”. From the perspective of a prominent creator of political humor, we can see the ways that even in the more open environment of Hong Kong, humor exists primarily, in the terms of De Certeau, as a “tactic…using existing shortcuts within the system” rather than as any sort of strategy to overthrow the system itself (Tan 2011).

1.2 Conclusion

This “tactical” quality of political humor could lead to a certain amount of cynicism regarding humor itself in terms of its transformative potential, as we have already discussed. And yet we hope readers can also learn from the studies presented here that political humor reveals a great deal about the political sensibilities of what Liu Xiaobo terms the “silent majority” (2012, 186), and how these sensibilities have both changed over time but also maintain certain core commonalities. For instance, it is evident that the prevalence of political cynicism in contemporary China and elsewhere is not a new phenomenon but has long existed in various forms, with citizens using humor to expose gaps between political ideals and practical realities since even before the 1911 Revolution. Indeed, the chapters here show the various ways that Chinese authorities have sought to channel political expression, the creative ways that citizens subsequently generate new means of communicating their views, and how humor is an undeniably vital part of this creativity.

Such constant inventiveness shows the persistent interest in exposing the failings of one’s political opponents as well as their political stance and agenda, and so political humor offers a valuable window onto political sentiments. The fact that many people find a particular cartoon or joke or performance funny is evidence of shared experiences and attitudes. What appears to be highly fragmented and individualized out of context, therefore, might hide a commonality when viewed in context. The openings that creators of political humor find in multiple levels of meaning or globalized modes of expression demonstrate the adaptability of humor to repressive circumstances, as well as its durability over time as a form of truth-telling. Even when one seek new ways to control political humor, whether through violent repression or moralistic warnings regarding proper uses of speech, this durability means that political humor will remain an essential way of understanding political sensibilities in a China that continues to be contradictory and ever-changing.

References

Abrahamsen, Eric. 2011. Irony is good! Foreign Policy. January 12. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/01/12/irony_is_good. Accessed 14 January 2011.

Bennett, W. Lance. 2007. Relief in hard times: A defense of Jon Stewart’s comedy in an age of cynicism. Critical Studies in Media Communication 24 (3): 278–283.

Benton, Gregor. 1988. The origins of the political joke. In Humor in society: Resistance and control. eds. Chris Powell and George E.C. Paton, 33–55. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Bergson, Henri. 1911. Laughter: An essay on the meaning of the comic. Trans. Cloudesley Brereton and Fred Rothwell. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.

Branigan, Tania. 2014. China bans wordplay in attempt at pun control. The Guardian, November 28, sec. World news. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/28/china-media-watchdog-bans-wordplay-puns?CMP=share_btn_fb. Accessed 4 March 2016.

Chey, Jocelyn. 2011. Youmo and the Chinese sense of humour. In Humour in Chinese life and letters: Classical and traditional approaches, eds. Jocelyn Chey and Jessica Milner Davis, 1–29. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Davis, Jessica Milner. 2013. Humour and its cultural context: Introduction and overview. In Humour in Chinese life and culture: Resistance and control in modern times, eds. Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey, 1–22. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Freud, Sigmund. 1985. The joke and its relation to the unconscious. In Classic comedies. Trans. & ed. Maurice Charney, 565–573. New York: New American Library.

Gong, Haomin, and Xin Yang. 2010. Digitized parody: The politics of egao in contemporary China. China Information 24 (1): 3–26.

Hu, Ping. 2013. Subversion by way of laughter. China Change. August 17. http://chinachange.org/2013/08/17/subversion-by-way-of-laughter/. Accessed 20 February 2016.

Link, Perry, and Kate Zhou. 2002. Shunkouliu: Popular satirical sayings and popular thought. In Popular China: Unofficial culture in a globalizing society, eds. Perry Link, Richard P. Madsen, and Paul G. Pickowicz, 89–109. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Liu, Xiaobo. 2012. From Wang Shuo’s wicked satire to Hu Ge’s egao: Political humor in a post-totalitarian dictatorship. In No enemies, no hatred: Selected essays and poems, eds. Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, and Liu Xia, 177–187. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Lukes, Steven. 1985. No laughing matter: A collection of political jokes. London; Boston: Routledge & K. Paul.

Morreall, John. 1987. A new theory of laughter. In The philosophy of laughter and humor, ed. John Morreall, 128–138. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Moser, David. 2004. Stifled laughter: How the Communist Party killed Chinese humor. Danwei. November 16. http://www.danwei.org/tv/stifled_laughter_how_the_commu.php. Accessed 6 February 2016.

Orwell, George. 1970. The collected essays, journalism and letters of George Orwell. eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus. Harmondsworth Middlesex: Penguin in association with Martin Secker and Warburg.

Rea, Christopher G. 2013. Spoofing (e’gao) culture in the Chinese Internet. In Humour in Chinese life and culture: Resistance and control in modern times, eds. Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey, 149–172. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Rea, Christopher, and Nicolai Volland. 2008. Comic visions of modern China: Introduction. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 20 (2): v–xviii.

Reuters. 2015. Al Qaeda claims French attack, derides Paris rally”, January 14. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-shooting-aqap-idUSKBN0KN0VO20150114. Accessed 6 March 2016.

Rorty, Richard. 1989. Contingency, irony, and solidarity. Cambridge. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tan, Shzr Ee. 2011. ‘Harmless’ and ‘hump-less’ political podcasts: Censorship and internet resistance in Singapore. Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 5 (1): 39–70.

Tao, Dongfeng. 2007. Making fun of the canon in contemporary China: Literature and cynicism in a post-totalitarian society. Cultural Politics 3 (2): 203–222.

The interview: A guide to the cyber attack on Hollywood. 2016. BBC News.. http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-30512032. Accessed 4 March 2016.

Wilson, Christopher P. 1979. Jokes: Form, content, use and function. London; New York: Published in cooperation with European Association of Experimental Social Psychology by Academic Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tam, Kf., Wesoky, S.R. (2018). Introduction. In: Tam, Kf., Wesoky, S. (eds) Not Just a Laughing Matter. The Humanities in Asia, vol 5. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4960-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4960-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-4958-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-4960-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)