Abstract

There is now ample evidence demonstrating the significant effects of parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling for children’s school success. Yet how these effects occur and what factors facilitate parent involvement are less well understood. This chapter will focus on understanding how parent involvement might exert its effects, including examining multiple forms of involvement (e.g., at school, at home), parents’ motivations for being involved (whether more controlled or autonomous), and whether involvement is provided in a more controlling versus autonomy-supportive manner. In addition, the chapter will provide evidence for a model in which parent involvement affects children’s achievement largely by facilitating children’s motivational resources of perceived competence, perceived control, and autonomous self-regulation. Further, it will address how multiple factors including parents’, teachers’, and principals’ attitudes and situations affect parents’ involvement. The chapter will stress the importance of a partnership model in which parents, teachers, and administrators must work together to ensure children’s school success.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

In the effort to increase children’s achievement and promote educational equality, parent involvement in children’s schooling has become a key focus of both researchers and practitioners. There is now strong evidence that parent involvement in children’s schooling is associated with children’s achievement and that this relation holds across diverse populations and contexts (e.g., for reviews, see Fan & Chen, 2001; Hill & Taylor, 2004; Jeynes, 2005, 2007; Pomeranz, Grolnick, & Price, 2005). With this knowledge in mind, increasing parent involvement has become a goal within many educational contexts.

While pursuing this goal should be applauded, it is important that key stakeholders do so with knowledge of the complexities of this important resource. In particular, it is important to consider (1) what types of involvement are most effective, (2) why parent involvement facilitates children’s achievement so that its effects can be maximized, (3) whether the way in which parents are involved makes a difference, and (4) what factors predict how involved parents become in their children’s schooling. It is also important to consider parents’ viewpoints to understand why they are involved, in that their own motivations may impact not only their levels of involvement but the way they become involved. This chapter takes up each of these issues. Using a Self-Determination Theory (SDT) perspective (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000), we explore how using a motivational model can help us to understand when, how, and why parent involvement is effective so as to maximize its impact for student motivation, achievement, and adjustment.

A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Parental Involvement

From an SDT perspective, children, as all humans, have three needs: those for autonomy, or to feel volitional and agentic; for competence, or to feel effective in their environments; and for relatedness, or to feel loved and valued. Given that parents are the primary socializing agents in children’s lives, whether children’s needs are satisfied within their day-to-day contexts is highly dependent on the degree to which parents create need-satisfying contexts. While parents affect children in a number of domains including social development, household responsibilities, and behavioral adjustment, they also play a key role in children’s school experience.

Parent involvement, defined as parents’ dedication of resources within a domain (Grolnick & Ryan, 1989; Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994), can be considered from the perspective of these three needs. First, when parents dedicate resources such as time, warmth, and more tangible resources such as books and assistance, children feel important and valued, thus fulfilling their need for relatedness. Parent involvement, however, needs to be provided in a way that supports children’s needs for autonomy and competence. In particular, parents can be involved in an autonomy-supportive or a controlling manner. When autonomy supportive, parents take children’s perspectives, help them solve their own problems, and encourage their initiatives. By contrast, when parents are controlling, they act from their own perspectives, solve problems for the children, and direct and pressure them to achieve in particular ways. Given children’s need for autonomy, parents’ involvement should be most beneficial when it is enacted in an autonomy-supportive manner. Second, involvement should be most effective when parents support children’s competence by providing a structured environment including clear guidelines, expectations, and information about how to be successful.

Another important tenet of SDT concerns the idea that individuals are active with respect to their environments. They develop beliefs and motives in response to their experiences in their environments, which then shape their behaviors. Thus, academic contexts, including those created by parents and teachers, impact children’s beliefs about their abilities and their motives, i.e., why they engage in school behaviors. In particular, when contexts support autonomy, children will be more likely to engage in school behaviors because they see value in these behaviors, rather than because they feel pressure to do so. With regard to competence, when contexts provide structure, children will be more likely to feel competent and to understand how to be successful and to avoid failure or have a sense of perceived control.

Having delineated the SDT framework, we now explore data on particular issues relevant to parent involvement. Across these issues, the extant data support the usefulness of an SDT perspective.

Types of Parent Involvement: Not All Behaviors Are Equally Effective

Parent involvement in children’s schooling has included a variety of activities and resources. Many researchers distinguish between two major types of involvement, that at school and that at home. Involvement at school includes activities such as going to school meetings, attending parent-teacher conferences, talking with teachers, and volunteering at school. Parent involvement outside of school includes helping children with homework, discussing school activities, and exposing children to intellectual activities that help to bring school and home together. Interestingly, when examining the effects of different types of involvement, several researchers have shown that it is the types of involvement that involve parent-child interaction, rather than those that focus on involvement at school, that are most effective. For example, McWayne, Hampton, Fantuzzo, Cohen, and Sekino (2004) showed that only supportive home learning (including talking to children about school activities and organizing the home to facilitate learning), but not direct involvement with the school, facilitated reading and math achievement. Hill and Tyson (2009) differentiated between school-based involvement, home-based involvement, and academic socialization, including providing support for children’s own educational and vocational aspirations, conveying the value of learning, and helping to make clear to children how learning activities connect to their interests. There were no effects of school-based involvement, modest effects of home involvement, and strong effects of academic socialization. These findings are in line with three meta-analyses: two conducted by Jeynes (2005, 2007), one involving studies of elementary-age children and one involving secondary schools, and one conducted by Fan and Chen (2001). In all three meta-analyses, there were stronger effects for academic socialization than for other practices, including assistance with homework, parental reading, and at-school participation.

Why would academic socialization-type behaviors have stronger effects than at-school behaviors and help with homework? One explanation is that parent involvement may have its most potent effects not by helping children with specific skills (e.g., math skills) or by changing teachers’ behaviors or attitudes but, rather, by facilitating children’s school-related motivation. In other words, through their involvement, parents may help children develop the beliefs and motives that would translate into higher levels of engagement in school activities and ultimately higher achievement. From an SDT viewpoint, these would be the very self-related beliefs and motives tied to the satisfaction of the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. More specifically, parent involvement would facilitate perceptions of competence and control tied to the need for competence, autonomous self-regulation tied to the need for autonomy, and feelings of connection tied to the need for relatedness.

Consistent with this reasoning, Grolnick and Slowiaczek (1994) proposed two models for understanding the effects of parental involvement, a direct effects model, in which parent involvement helps children by providing them specific academic skills, and a motivational model, in which parent involvement facilitates children’s success by helping them to build key motivational resources. They tested the motivational model in a study of 302 seventh grade children and their mothers and fathers. Three types of involvement were measured. School involvement concerned involvement in school activities and events, such as parent-teacher conferences and volunteering at school. Cognitive/intellectual involvement included parents exposing children to stimulating events such as museums and current events. Personal involvement was parents’ display of interest and expectations for their children in school. In this study, children’s motivational resources were also measured, and grades and achievement scores were obtained. Path analyses supported the indirect effects model for both mothers and fathers whereby involvement facilitated the motivational resources of perceived competence and perceived control which then predicted school grades. Marchant, Paulson, and Rothlisberg (2001) similarly measured fifth and sixth grade children’s perceptions that their parents were involved by valuing doing well in school and by participating in school activities and events. Only perceptions that parents valued school performance and effort were associated with children’s perceiving that ability, effort, and grades were important as well as their perceptions of competence in school. These motivational variables were then associated with children’s grades. In a sample of younger children (7 years old), Topor, Keane, Shelton, and Calkins (2010) found that teachers’ perceptions of parent involvement (that they showed a value for and interest in school) predicted children’ academic perceived competence, which then predicted their achievement.

How Involvement Is Conveyed Matters

While research clearly attests to its positive effects, parent involvement can be conveyed in different ways, and this may influence how it affects children. Importantly, parents can be more autonomy supportive or more controlling in the way they are involved in school endeavors. In addition, they can be involved in a way that does or does not include providing the structure that would increase feelings of competence. We take up each of these issues, beginning with autonomy support.

Involvement: Autonomy Supportive vs. Controlling

Whether it is the way they discuss and deal with children’s grades or how they help with homework, parents can convey attitudes and behaviors that either support children’s initiations and encourage them to solve problems or ones that pressure children and solve problems for them. SDT would suggest that more controlling involvement should undermine children’s experience of autonomy. In this case, children’s motivation would tend to be external, with children engaging in schoolwork and homework because of contingencies (rewards and punishments) or introjects (engaging in behaviors to avoid negative self-related affects such as guilt). Controlling behaviors should prevent children from internalizing the value of their own learning and thus engaging in behaviors because they see them as important for their own self-valued goals (identified motivation). Further, during interactions, controlling parental behaviors may prevent children from internalizing the information that is being conveyed. When children are directed and pressured to learn, they are less likely to process information deeply and have it available later (Grolnick & Ryan, 1987).

To address the issue of autonomy-supportive versus controlling involvement, several researchers have examined parental styles during homework-like tasks. Grolnick, Gurland, DeCourcey, and Jacob (2002) had 60 third grade students and their mothers engage together in homework-like tasks – a map task where children had to describe how to get to locations on a map and a poem task, where children had to identify different forms of quatrains (four-lined rhyming poems). Mothers’ behavior during the tasks was rated from videotapes for how controlling (e.g., directing the child when he or she was progressing well; providing answers to the children) versus autonomy supportive (providing needed information; giving feedback) their behavior was. After the parent-child interaction, children were asked, unbeknownst to the children and the parents, to do similar map and poem tasks on their own. Results suggested that, controlling for children’s school grades as a measure of academic competence, the more controlling the mothers, the less accurate the children were on the quatrain and map tasks when on their own. Further, children of mothers who were more controlling and less autonomy supportive during the interactive poem task wrote less creative poems when asked to write a poem on their own relative to children whose mothers were more autonomy supportive. In analyzing these poems, the children of the more controlling mothers tended to repeat the themes of the poem they wrote with their mothers.

The results of the Grolnick et al. (2002) study suggest the importance of an autonomy-supportive style during interactions around school work. While parents who are controlling may try to help their children by giving them answers and solving problems for them, such behaviors seem to prevent the deep processing and internalization of information such that it can be used independently. By contrast, autonomy-supportive interactions appear to help children internalize information so that it can be readily used when necessary. We explore another aspect of this study – different instructions that do or do not provide pressure on parents to have their children do well – on mothers’ behavior. This aspect of the study helps us to understand why some parents may adopt a more controlling style, even when they may not endorse such behaviors.

A study by Kenney-Benson and Pomerantz (2005) also examined parent-child interactions during homework-like tasks in a sample of 7–10-year-olds. Mothers’ behavior was rated on a scale from controlling to autonomy supportive. Children also completed questionnaires about perfectionism and depression. Findings showed that the more controlling parents were, the more children reported perfectionism and depression. Further, path analyses showed that the effects of controlling maternal behavior on depression were mediated by children’s perfectionism. Thus, parent control seemed to translate into children’s developing controlling standards for their own performance, something that had negative implications for their well-being.

There is also some evidence from field studies that parent involvement has more positive effects when conveyed in an autonomy-supportive style. Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, and Darling (1992) had 14–18-year-olds report on their parents’ involvement in school, which included helping with homework, attending school activities and events, and helping with choosing classes. They also measured children’s perceptions of their parents’ overall styles, dividing them into more authoritative (autonomy supportive and structured), authoritarian (controlling and structured), and permissive (unstructured). They found that parent involvement had its most positive effects when combined with an authoritative style. The positive effects of parent involvement were attenuated when parents were either authoritarian or permissive.

Given the importance of how parents are involved, we later address what may make parents more controlling in interacting with their children, focusing on pressures parents may feel to have their children perform well. We also address how teachers may help to decrease the level of pressure parents feel. But next, we discuss how parents can provide structure at home to help their children succeed.

When Parents Provide Structure

While autonomy support has received some attention in the literature, parental structure has been studied less. Within an SDT framework, structure concerns the organization of the environment to facilitate competence. Parents provide structure for their children when they make clear their expectations and rules, provide feedback about how children are doing in meeting these expectations, and provide consistent consequences for action. When these aspects of structure are in place, children know how to be successful and should feel competent to do so.

Farkas and Grolnick (2010) studied the effects of parental structure within the academic domain. In particular, they interviewed seventh and eighth graders about studying and homework and, in particular, whether their parents provide rules and expectations, feedback about how they are doing, consistent consequences for rule-breaking behavior, rationales for why they implement rules and expectations, and, in general, whether they act as authorities in the home. Raters coded the interviews and ratings of these different aspects of structure were combined. These authors found that the more parents provided structure, the higher were children’s perceptions of control of their school successes and failures and the more competent they felt in school.

Building on this work, Grolnick et al. (2014b) measured both parents’ provision of structure and whether they provide structure in an autonomy-supportive or controlling manner with their children in three areas: academics, unstructured time, and responsibilities. Providing structure in an autonomy-supportive manner involves jointly establishing rules and expectations (versus parents dictating rules and expectations without child input), allowing for open exchange about rules and expectations, providing empathy about the child’s viewpoint on the rules/expectations, and providing choice in how the rules were to be followed. Within the academic domain, how structure was provided was more important than the level of structure itself. More specifically, when parents provided structure in an autonomy-supportive manner, children felt most competent (and parents perceived them as most competent), felt more in control of school outcomes, and evidenced higher levels of engagement and school grades.

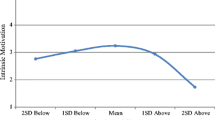

In another study (Grolnick et al. 2014a), the importance of parental structure was examined at the transition to middle school. The authors reasoned that the transition to middle school involves a series of changes including a new and larger school, a move from one teacher and classroom to multiple teachers and classrooms, higher expectations from teachers, and more controlling classrooms. Such changes would challenge children’s perceptions of how to succeed and their sense of their own competence and autonomy. We reasoned that parental structure would buffer children from declines in such motivation and self-beliefs at this transition. One-hundred and thirty-six 6th grade students were interviewed about parental structure at sixth grade and then followed into seventh grade as they made the transition to middle school. Results showed that children in homes with higher level of structure were buffered from declines in perceived competence, intrinsic motivation, and English grades relative to those in homes with lower levels of structure. Further, the more autonomy supportive the structure provided, the higher children’s perceived competence, autonomous motivation, and English grades. Thus, it appears that, by providing autonomy-supportive structure, parents can help their children weather the challenges of this important transition.

Predictors of Involvement

If educators are to increase parent involvement, it is important to understand the factors that are associated with differing levels of parent involvement. Further, it is important to know why parents become involved. We take up each of these in turn.

Factors Affecting Parents’ Level of Involvement

Several studies have shown that demographic factors such as parent education, income, and single-parent status predict parent involvement (e.g., Bogenschneider, 1997; Stevenson & Baker, 1987). However, this may be more the case for some forms of involvement than others. For example, Grolnick, Benjet, Kurowski, and Apostoleris (1997) found that SES was more strongly related to parents’ school and cognitive/intellectual involvement than their personal involvement. Undoubtedly, the time and resources one needs to be involved in these ways make it more difficult for less advantaged families to be involved. Parents from disadvantaged backgrounds may want to be involved but are able to do so in only certain ways. This point will be discussed later as we consider the implications of research findings for educators hoping to increase parent involvement in their schools.

Beyond these background factors, however, researchers have looked at contextual and attitudinal factors that impact levels of involvement. For example, in one study, controlling for SES, parents who reported more stressful life events and lower levels of social support were less likely to be involved, especially for mothers of boys (Grolnick et al., 1997). Taking the view that parents are active in determining how they distribute their time and resources, several studies have examined how parents see their role in children’s learning and achievement as predictors of involvement. For example, Grolnick et al. found that parents who saw their role as that of their children’s teachers were more likely to get involved in cognitive activities with their children relative to those who were less likely to endorse this role. Green, Walker, Hoover-Dempsey, and Sandler (2007) showed that parents who believed that parents should be active in children’s educations showed higher levels of home and school involvement relative to those who did not have these beliefs. Finally, Walker, Ice, Hoover-Dempsey, and Sandler (2011) measured three types of role constructions – one where parents thought they had primary responsibility for their children’s school performance, one where they believed they had shared responsibility with the school for children’s school performance, and one where the school had primary responsibility for children’s school performance. In a study of 147 Latino parents, these authors found that parents who endorsed the shared responsibility role construction were more likely to be involved at home, whereas those who believed the school had primary responsibility were less involved at home.

Taking parents’ viewpoints even more seriously, we have focused on parents’ own motivation for being involved as a factor that may affect their behavior. Just as we have shown that whether children’s participation in school endeavors is more autonomous or more controlled has implications for their school functioning and adjustment, we wondered whether parents whose involvement behaviors were experienced as more versus less autonomous would have different experiences and levels of involvement. Thus, in a diverse sample of 178 mothers and their third through sixth grade children (Grolnick, 2015), we asked mothers why they were involved in three types of activities: talking to your child’s teacher (e.g., conferences and meetings), participating in events at your child’s school (e.g., fund-raisers or volunteering), and helping your child with his or her schoolwork. Parents then rated their reasons for being involved in each of these activities. Reasons were associated with the four types of motivation: external (e.g., because I am supposed to), introjected (e.g., because I would feel guilty if I didn’t), identified (e.g., because I think it is important to talk with the teacher), and intrinsic (e.g., because it is fun to go to the events). Parents also reported on their affect when involved (i.e., interested, relaxed, calm, nervous, strained, bored) and their levels of school, cognitive/intellectual, and personal involvement. Finally, children reported on their perceptions of competence and children’s grades were obtained. Results showed that mothers’ motivation for involvement had both affective and behavioral concomitants. In particular, mothers’ external and introjected motivation for involvement were associated with lower levels of positive affect when involved, while mothers’ identified and intrinsic motivation were positively associated with positive affect. In addition, identified and intrinsic motivations were associated with higher levels of school, cognitive/intellectual, and personal involvement. Introjected motivation was negatively associated with school and personal involvement, and external motivation was negatively associated with personal involvement. Finally, the results supported a pathway in which more identified motivation for involvement was associated with higher levels of cognitive/intellectual involvement, which then predicted children’s perceived competence and reading grades. In addition, identified motivation was associated with children’s self-worth through increased personal involvement.

The results of the study on mothers’ motivation for involvement underscore the importance of considering why parents are involved for both their level of involvement and for parents’ experience. That the strongest results were for identified motivation suggests that it is crucial for parents to be involved because they see their involvement as important for their own goals vis-a-vis their children rather than because of regulations and contingencies. Pushing parents to be involved through contingencies or guilt evoking may result in some increases in involvement, but if this results in more external and introjected motivation, these increases are unlikely to be sustained. Further, they may result in parents feeling unhappy when involved, and this may translate into uncomfortable interactions with children. Since positive affect during homework has been found to moderate children’s feelings of helplessness on tasks (Pomerantz, Wang, & Ng, 2005), facilitating motivation in parents that is likely to be more autonomous needs to be a goal in efforts to involve parents.

Though not examining levels of involvement per se, a study by Katz, Kaplan, and Buzukashvily (2011) assessed parents’ autonomous versus controlled motivation for homework involvement by asking parents to respond to questions about why they help their children with homework. These authors found that the more autonomous parents’ motivation for helping their children with homework, the more they showed need-supportive behavior (i.e., were perceived by students and reported themselves as providing support for autonomy (i.e., understanding students’ perspectives, offering choice, allowing for criticism), support for children’s competence (e.g., helping students to plan, offering feedback), and support for relatedness (i.e., providing acceptance and empathy). In turn, the more need-supportive behavior parents displayed, the more students reported autonomous motivation for completing their homework. Thus, again, parents’ motivation for involvement must be considered if involvement is to be most facilitative.

What Affects the How of Involvement?

Results described earlier showed that higher levels of involvement were positive for school achievement but also that more autonomy-supportive involvement had the most robust effects on motivation and performance. Therefore, it is important to study what predicts whether parents are more or less autonomy supportive in their school-related involvement.

Within our framework, pressure is a key factor in predicting parental autonomy support versus control. Pressure, whether it is from external demands, internal pressures to have children succeed, or a result of the children themselves pushing parents, narrows one’s focus on the outcome and would thus lead parents to make the quickest and most expedient response to assure it. Oftentimes, this involves controlling children’s behavior, since autonomy-supportive behaviors, such as taking children’s perspectives and engaging in joint problem-solving, take time and require a focus on the process of the interaction not just the outcome.

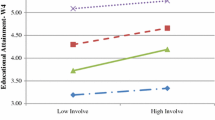

Consistent with this reasoning, in our lab, we have examined how pressure on parents to have their children succeed influences the degree to which parents interact with their children in more autonomy-supportive versus controlling ways. In one study (Grolnick et al., 2002), 60 mothers worked on map and poem tasks with their third grade children. Mothers completed questionnaires about their orientations toward being controlling or supporting autonomy in children. Then half of the mothers received pressure to have their child perform by being told “Your role is to ensure that your child learns to give directions [write a poem]. We will be testing him/her after to make sure that he/she performs well enough.” The other half received a non-pressuring orientation, “Your role is to help your child learn how to give directions [write a poem]. We will be asking him/her some questions after but there is no particular level at which he/she needs to perform.” Mothers’ behavior during the tasks was coded for level of autonomy support versus control. For the poem task, mothers in the pressuring condition were more controlling than those in the non-pressuring condition, directing the children and solving problems for them. For the map task, there was an interesting statistical interaction in which mothers who displayed highly autonomy-supportive attitudes toward working with children were not affected by the pressuring condition. On the other hand, mothers who believed strongly in control were much more controlling in the high-pressure condition than in the low-pressure condition. These results show how pressure can “roll downhill” and affect interactions with others. It also shows that some parents may be more vulnerable to pressure to have their children do well. The implications of these findings for helping parents work with their children in a motivation-enhancing manner are discussed at the end of the chapter.

Another factor that may predict parents’ autonomy-supportive versus controlling school-related interactions concerns parents’ ideas about their children’s intelligence. A body of work suggests that children who believe intelligence is fixed and not changeable (i.e., have an entity theory of intelligence) show decrements in their performance on tasks when work gets difficult (e.g., Dweck & Leggett, 1988). The interpretation of this is that, when children believe their intelligence is unchangeable, difficulties and setbacks would be an indication that they are not “smart” and there is nothing they can do about it. They become helpless – giving up and denigrating their capacities. By contrast, those who have an incremental theory, seeing intelligence as changeable and able to be increased, show more effort when faced with setbacks. Pomerantz and her colleagues have examined parents’ ideas about children’s intelligence. They reasoned that parents who have an entity mind-set regarding their children’s intelligence would see children’s mistakes and setbacks as indicative of a permanent deficit in their competence. They would thus try to ensure that they perform well. This might lead to unconstructive interactions with parents more controlling and negative in their affect. On the other hand, mothers with an incremental mind-set would see difficulties as signs only that their children need to display more effort to master tasks. They would be less concerned about performance. In one study (Moorman & Pomerantz, 2010), these authors induced 79 parents to have either an entity mind-set by telling them that the task their child was about to complete measured innate intelligence and children’s performance on the task was stable or an incremental mind-set, by telling them that children’s performance on the task measured potential and was highly changeable through practice and learning. Mothers then worked on the tasks with their children, helping them as much as they wanted. The researchers coded mothers’ behaviors for whether they were pressuring and intrusive or encouraging of mastery. They also coded children’s responses to challenge for level of helplessness (i.e., frustration) versus engagement. Results showed that mothers induced to have an entity mind-set were more unconstructive in their involvement. In addition, when children showed signs of helplessness, mothers in the entity condition engaged in more unconstructive involvement. The results of the study show that parents’ beliefs about children’s intelligence may play a role in how they interact with their children on school-related tasks.

Consistent with the idea of pressure from below, investigators have found that the lower children’s achievement, the more parents are controlling in their assistance with their children’s homework. For example, Dumont, Trautwein, Nagy, and Nagengast (2014) measured how controlling parents were in helping their children with their homework when children were in fifth and seventh grades. They found that children with lower levels of reading achievement at fifth grade received more control from their parents 2 years later relative to children with higher levels of achievement. In a further aspect of the study looking at reciprocal relations between parents’ and children’s behavior, lower levels of achievement led to more parental control which in turn led to children procrastinating more on their homework and then in turn to lower levels of achievement. Such results refute the often stated idea that children performing poorly require more controlling styles. Findings of the study indicate that, though they may elicit them, unfortunately, controlling interventions do not appear to help them move toward greater self-regulation and academic performance.

Pomerantz and Eaton (2001) explored the mechanisms through which children’s achievement might elicit more controlling behaviors on the part of mothers. These authors had mothers complete a checklist of behaviors they used when assisting their children with homework. Some of these behaviors, such as helping with or checking homework when their child did not request it, were labeled intrusive support. The authors found that the lower children’s achievement, the more mothers used intrusive support behaviors. Further, they found that children’s achievement elicited parental worry and signals of uncertainty from children which were then associated with intrusive support. Thus, parental worry and concern, which may be well meant, may result in pressuring their children.

In sum, there are a variety of factors that influence both the level and the quality of involvement parents display in their children’s academic lives. These factors need to be addressed in efforts to involve parents as they can be the difference between involvement that it is facilitative and undermining of children’s motivation and adjustment.

Implications and Recommendations

The research on parent involvement is extensive and makes it clear that enhancing parent involvement should be a goal for all schools. The research provides key information on how to maximize efforts to harness this key resource for children’s motivation and learning. Some ideas and suggestions are described below.

-

1.

Encourage diverse ways to be involved

When people think about parent involvement, they most likely imagine parents coming to school for open school night or being active in fund-raising or volunteering. Not all parents, however, are able to attend activities at school given work schedules, other responsibilities, lack of transportation, or language barriers. Given that research evidence suggests that the most potent forms of involvement are those that involve parent-child interaction, teachers and schools can involve parents in other ways. Frequent communication through e-mails and newsletters helps parents to be able to know what is going on in school so that they can discuss it with their children. Schools can also provide information to parents so that they might help their children manage their time, select courses, and engage in activities related to school topics. As described in the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) project (Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001), teachers may assign homework involving family members such as interviewing them about earlier times. Finally, schools can invite parents to the classroom to see their children present their work or share their own interests and cultural activities. Given that parent involvement has its largest effects through children’s motivation, all parents can be involved in ways that will support their children.

-

2.

Help parents create meaningful and facilitative roles

Research shows that parents who believe their role is that of their child’s teacher and who believe they share responsibility for their children’s learning with the school are more likely to be involved. Schools may expect that parents know they have a crucial role in their children’s school success but may not convey this expectation. Thus, schools may interpret parents’ lack of involvement as evidence that they are not interested in being involved. It is crucial, therefore, that schools convey their expectations and the value that they have for families. Teachers and principals can do this by sharing their philosophy via communications such as newsletters and explicitly addressing how important parents are during parent-teacher conferences and school events.

Beyond knowing that they are part of the home-school partnership team in helping their children, parents need to know what role teachers expect them to play in their children’s homework and studying. Parents have a strong stake in their children doing well in school. They may become highly invested in children’s performance outcomes, especially if they see intelligence as a fixed entity and feel that their performance reflects this highly valued trait. This situation may lead parents to push and pressure their children when working with them at home, which may lead to negative homework interactions that are quite prevalent among families (Xu & Corno, 2003). Teachers can prevent this situation by helping parents to see their role as to support children’s initiations and provide needed resources rather than ensuring that their homework makes them look “smart.” When parents receive the message that their children’s mistakes and questions do not reflect on them or on their children’s potential, they may be more likely to have positive interactions around schoolwork in which children feel supported to convey their misconceptions and their struggles as well as successes.

-

3.

Meet Parents’ Needs

Our research, reviewed previously, showed that parents’ own motivation for being involved plays a role in their levels of and experience of involvement. When parents have more autonomous motivation for being involved, in particular, when they are involved because they see the importance of their behaviors rather than because they feel they are supposed to or would feel guilty if they didn’t, they have more positive experiences and higher levels of involvement. Just as parents can set up facilitative conditions for their children’s motivation, schools can help to set up situations that may lead to parents’ more autonomous involvement. In particular, in asking parents to be involved, schools can provide clear rationales for how parents’ actions will be helpful to the school and to their children. They can also provide clear expectations so that parents know how to be most helpful to their children. These actions can help parents to feel competent in working with their children and with the school. Second, to support parents’ sense of autonomy, schools can provide choices for how parents can be involved so that they can engage in the activities that fit them best. Finally, establishing mutual relationships at the start of the school year can provide a context within which requests and opportunities for involvement are welcomed. While many school-to-parent communications occur when children are experiencing problems, some schools initiate contact with parents when something is positive or just to establish a working relationship. While touching base with parents before problems arise may be time-consuming, it may ultimately result in a stronger school-home alliance that will pay off many times in the long run. Of course, parent-school interactions are a two way street. Parents can help to meet teachers’ basic needs by valuing and respecting them, communicating their expectations, and establishing a context of joint problem-solving and partnership.

In sum, our review of work on parent involvement supports the usefulness of an SDT framework in understanding how parent involvement exerts its effects on children’s achievement. The theory highlights the important role that parents play in facilitating children’s motivation and the factors, including pressures from various sources that undermine parents’ own motivation to be involved. Schools can play an important role in creating contexts that welcome and encourage parents’ support of their children’s learning. Our hope is that schools will increasingly prioritize and nurture this crucial resource.

References

Bogenschneider, K. (1997). Parental involvement in adolescent schooling: A proximal process with transcontextual validity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 718–733.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 319–338.

Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Nagy, G., & Nagengast, B. (2014). Quality of parental homework involvement: Predictors and reciprocal relations with academic functioning in the reading domain. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 144–161.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

Epstein, J. L., & Van Voorhis, F. L. (2001). More than minutes: Teachers’ roles in designing homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 181–193.

Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 1–22.

Farkas, M. S., & Grolnick, W. S. (2010). Examining the components and concomitants of structure in the academic domain. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 266–279.

Green, C. L., Walker, J. M. T., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (2007). Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical motel of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 9, 532–544.

Grolnick, W. S. (2015). Mothers’ motivation for involvement in their children’s schooling: Mechanisms and outcomes. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 63–73.

Grolnick, W. S., Benjet, C., Kurowski, C. O., & Apostoleris, N. (1997). Predictors of parent involvement in children’s schooling. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 538–548.

Grolnick, W. S., Gurland, S., DeCourcey, W., & Jacob, K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of mothers’ autonomy support. An empirical investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38, 143–155.

Grolnick, W. S., Raftery-Helmer, J. N., Flamm, E. S., Marbell, K., Cardemil, E. V. (2014a). Parental provision of academic structure and the transition to middle school. Journal of Research on Adolescence. doi:10.1111/jora.12161

Grolnick, W. S., Raftery-Helmer, J. N., Marbell, K., Flamm, E. S., Cardemil, E. V., & Sanchez, M. (2014b). Parental provision of structure: Implementation, correlates, and outcomes in three domains. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 60, 335–384.

Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). Autonomy in children’s learning: An experimental and individual difference investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 890–898.

Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 143–154.

Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 65, 237–252.

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45, 740–763.

Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. P. (2004). Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement: Pragmatics and issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 161–164.

Jeynes, W. H. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education, 40, 237–269.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42, 82–110.

Katz, I., Kaplan, A., & Buzukashvily, T. (2011). The role of parents’ motivation in students’ autonomous motivation for doing homework. Learning and Individual Differences, 21, 376–386.

Kenney-Benson, G. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2005). The role of mothers’ use of control in children’s perfectionism: Implications for the development of children’s depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73, 23–46.

Marchant, G. J., Paulson, S. E., & Rothlisberg, B. A. (2001). Relations of middle school students’ perceptions of family and school contexts with academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools, 38, 505–519.

McWayne, C., Hampton, V., Fantuzzo, J., Cohen, H. L., & Sekino, Y. (2004). A multivariate examination of parent involvement and the social and academic competencies of urban kindergarten. Psychology in the Schools, 41, 363–377.

Moorman, E. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2010). Ability mindsets influence the quality of mothers’ involvement in children’s learning: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1354–1362.

Pomerantz, E. M., & Eaton, M. M. (2001). Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: Transactional socialization processes. Developmental Psychology, 37, 174–186.

Pomerantz, E. M., Wang, Q., & Ng, F. Y. (2005). Mothers’ affect in the homework context: The importance of staying positive. Developmental Psychology, 41, 414–427.

Pomeranz, E. M., Grolnick, W. S., & Price, C. E. (2005). The role of parents in how children approach school: A dynamic process perspective. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), The handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 259–278). New York: Guilford.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63, 1266–1281.

Stevenson, D. L., & Baker, D. P. (1987). The family-school relation and the child’s school performance. Child Development, 58, 1348–1357.

Topor, D. R., Keane, S. P., Shelton, T. L., & Calkins, S. D. (2010). Parent involvement and student academic performance: A multiple mediational analysis. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 38, 183–197.

Walker, J. M. T., Ice, C. L., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (2011). Latino parents’ motivations for involvement in their children’s schooling. The Elementary School Journal, 111, 409–429.

Xu, J., & Corno, L. (2003). Family help and homework management reported by middle school students. Elementary School Journal, 103, 503–536.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Singapore

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Grolnick, W.S. (2016). Parental Involvement and Children’s Academic Motivation and Achievement. In: Liu, W., Wang, J., Ryan, R. (eds) Building Autonomous Learners. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-630-0_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-630-0_9

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-287-629-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-287-630-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)