Abstract

Parental educational involvement during middle school has received increased attention from researchers and policymakers because of its links to a variety of academic outcomes. Despite this increased attention, parental involvement has been inconsistently linked to academic outcomes among adolescents, indicating different types and levels of involvement that may be more beneficial for adolescents. Therefore, this study examined the nonlinear associations between parental involvement (home-based involvement and academic socialization) and academic motivation in an effort to better understand the nature of parental involvement in middle school. Using data from an ethnically diverse (57 % Black/African American, 19 % multiracial, 18 % White/Caucasian, 5 % Hispanic or Latino, and 1 % Asian American) sample of 150 adolescents (56 % female) in grades 6 through 8, findings showed no associations between home-based involvement and intrinsic or extrinsic motivation. There was, however, a significant nonlinear association between academic socialization and both types of motivation. More specifically, the positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation was attenuated at high levels of academic socialization. There was no association between academic socialization and extrinsic motivation at low and moderate levels, but there was a positive association at high levels of academic socialization. These findings suggest that different types of involvement and greater amounts of parental involvement may not always benefit adolescents’ academic motivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parental educational involvement has gained widespread attention from political and professional communities as a key factor related to students’ academic success (e.g., No Child Left Behind [NCLB], 2002). Notably, the NCLB Act of 2001 explicitly ties federal funding to school programs that encourage parental educational involvement. While this legislation emphasizes the family–school connection, it does not provide clear direction as to how or how much parents should be involved. This is particularly important to consider during middle school, at which time the nature of parental involvement may shift away from parents’ direct involvement at school (e.g., volunteering in classrooms) and other involvement strategies (e.g., communicating the value of an education) may become more salient (Hill and Chao 2009).

Many studies provide evidence that parental educational involvement is positively linked to academic outcomes among adolescents (e.g., Jeynes 2003; Karbach et al. 2013). Greater amounts of involvement, however, may not always be beneficial, as some researchers have found that involvement is unrelated or negatively related to youth’s academic outcomes (Pomerantz et al. 2007). Previous studies have not fully investigated the extent to which different types of involvement are associated with adolescents’ academic outcomes, which may explain these mixed findings. Further, much of the literature to date has focused on achievement outcomes rather than motivational outcomes, which are key components of school success (Gottfried et al. 2001; Lepper et al. 2005). In the current study, we sought to fill these gaps by examining the nonlinear relations among two types of parental involvement (home-based involvement and academic socialization) and academic motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic motivation). We used nonlinear associations to statistically model the extent to which each type of involvement was linked to motivation. We examined each type of involvement separately to disentangle previously mixed findings regarding the benefits of parental involvement and to better understand the nature of parental involvement in middle school.

Theoretical Frameworks

Theories of parental involvement, along with self-determination theory, informed the present study by providing a foundation for understanding the links between parental involvement and adolescent academic motivation. The construct of parental educational involvement is generally defined as “…parents’ work with schools and with their children to benefit their children’s educational outcomes and future success” (Hill et al. 2004, p. 1491). Theory on parent educational involvement has emphasized it as a multidimensional construct (e.g., Epstein 2001; Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2009). The dimensions of involvement generally include direct and indirect forms of involvement. Direct parental involvement includes parents’ direct contact with school, at school, and with school work. Indirect parental involvement includes parents’ communication about school and modeling of the importance of an education (Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler 1995). Theorists have noted that indirect involvement strategies, such as academic socialization (parents communicating the value of an education), may be less intrusive and more appropriate for adolescents than other direct strategies (Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2009).

Ryan and Deci’s (2000b) self-determination theory provides an excellent framework for understanding the importance of parents’ use of autonomy-supportive involvement strategies to support adolescents’ academic motivation. Self-determination theory posits that “…social contexts that support people’s being competent, related, and autonomous will promote motivated action” (Deci et al. 1991, p. 332). In contrast, when people feel forced or pressured into action, they will be less responsive than when they feel they are making choices on their own (Wehmeyer et al. 2003). Contexts that promote competence, relatedness, and autonomy have been linked to adolescents’ positive social functioning, intrinsic motivation, and personal well-being (Ryan and Deci 2000a).

Parental educational involvement is a social context that has the potential to support or undermine adolescent competence, relatedness, and autonomy. For example, parents may use involvement strategies at levels that support an adolescent’s sense of self-determination and are linked to beneficial outcomes such as intrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci 2000b). In contrast, parents may use involvement strategies at levels where adolescents feel forced into actions or beliefs, therefore undermining their sense of autonomy and subsequent positive outcomes. There is evidence that types of parental involvement, such as home-based strategies and academic socialization, are associated with motivation (Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005), but high levels of these forms of involvement may inadvertently undermine parents’ educational involvement efforts because adolescents might feel stripped of their autonomy (Pomerantz et al. 2007).

Parental Involvement and Motivation During Middle School

Early adolescence is an important developmental period to study parental involvement and its link to academic motivation because it is a time when youth experience rapid biological, social, and cognitive changes (Archibald et al. 2008; Casey et al. 2008). These developmental changes often coincide with a transition to middle school, which can lead to declines in motivation, self-confidence, school grades, and increases in test anxiety (Eccles and Roeser 2009). However, at the same time, the importance of academic motivation increases because of its concurrent and prospective links to task persistence, anxiety, and achievement outcomes, particularly as students may be placed into academic tracks that have implications for high school and beyond (Eccles and Harold 1996; Lepper et al. 2005; Schunk et al. 2008). There is clearly a mismatch between the increased importance of associations between academic motivation and students’ outcomes and the declines in academic motivation that occur during middle school, prompting researchers to investigate parental involvement as an important factor associated with promoting motivation (Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005).

Despite the intended benefits of parents’ educational involvement throughout adolescence (e.g., Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005), parents tend to be less involved during middle school than elementary school (Singh et al. 1995) and some researchers have argued that the strength of the relation between involvement and achievement declines during middle school (Singh et al. 1995). However, it may be the case that parents adjust their involvement strategies due to developmental changes during early adolescence and thus use strategies that are more appropriate for the middle school years compared to elementary school. For instance, academic socialization may be more developmentally appropriate for adolescents in middle school because it scaffolds their “burgeoning autonomy, independence, and cognitive abilities” (Hill and Tyson 2009, p. 758). Following, the present study investigated two forms of parental involvement—home-based and academic socialization—in an effort to more fully understand how two distinct types of parental involvement may be differentially associated with intrinsic and extrinsic motivation during adolescence.

Intrinsic motivation is a person’s desire to seek out and engage in new experiences, challenges, and learning opportunities because they are inherently rewarding (Ryan and Deci 2000a). Students who are intrinsically motivated typically enjoy and value the learning process, report lower levels of anxiety, persist in the face of failure, and seek opportunities for engaging in difficult and new tasks (Gottfried 1985; Ryan and Deci 2000a; Schunk et al. 2008). Most importantly, intrinsic motivation is a key component of adolescent academic success because it is a factor in the learning process that is amenable to change (Ryan and Deci 2000a).

Extrinsic motivation is a person’s desire to engage in a task for its instrumental value or as a means to an end, rather than because the task is inherently rewarding (Ryan and Deci 2000a). Extrinsic motivation is not simply the opposite of intrinsic motivation, as it has been only moderately correlated with intrinsic motivation in previous studies (Hayenga and Corpus 2010; Lepper et al. 2005; Schunk et al. 2008). Extrinsic motivation has been associated with lower grades, standardized test scores, and engagement (Lepper et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2006). Recent research highlights the importance of environmental influences, such as parental involvement, which can enhance or diminish intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Deci et al. 1991; Fan and Williams 2010; Ryan and Deci 2000a).

Home-Based Involvement and Motivation

Scholars have noted that parental involvement strategies are linked to adolescents’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, but no clear conclusions have been drawn regarding the benefits of home-based involvement for adolescents (e.g., Fan and Williams 2010; Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005). Home-based involvement strategies are commonly defined as educational involvement that occurs in the home environment, including behaviors such as checking homework, monitoring school assignments, and proofreading assignments (Hill and Tyson 2009). Spera (2006) examined the association between parents’ involvement in schoolwork and seventh and eighth grade students’ interest in school and found that greater levels of parental involvement with school work predicted more interest in school and school motivation among adolescents. In contrast, Ginsburg and Bronstein (1993) found that fifth graders reported lower levels of intrinsic motivation when their mothers were highly involved with homework (i.e., reminding adolescents about homework or checking homework). The authors explained these findings by noting that the adolescents may have perceived this involvement as excessive, invasive, and controlling. Findings from these studies suggest that home-based parental involvement, such as help with schoolwork, may be beneficial for intrinsic motivation to a certain extent and that too much involvement may undermine intrinsic motivation.

Although less work has been done to examine the association between home-based involvement and extrinsic motivation, past research indicates a positive association between home-based involvement and extrinsic motivation (see Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005 for review). For example, in their study investigating school motivation, Ginsburg and Bronstein (1993) found an increase in extrinsic motivation for fifth graders when their mothers were more involved with their school work. It is important to note, however, that a limitation of this study is that the authors measured intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as two ends on the same continuum rather than as distinct constructs. Further, as noted previously, home-based involvement was considered to be overly controlling in this study, suggesting that it may just be high levels of help with schoolwork that are associated with an increase in extrinsic motivation. The lack of additional studies examining this association warrants further investigation of the link between home-based involvement and extrinsic motivation during adolescence.

Academic Socialization and Motivation

Academic socialization refers to parental involvement strategies that include parents communicating the value or utility of an education to their adolescent to promote academic success and foster a “link between school work and future goals and aspirations” (Hill and Tyson 2009, p. 758). Generally, findings have shown a positive link between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation (e.g., Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005), while no studies have investigated the link between academic socialization and extrinsic motivation. Marchant et al. (2001) examined the indirect link between parental academic socialization and academic achievement via motivation among early adolescents (fifth and sixth graders). Findings suggested a positive link between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation: The more adolescents reported their parents expressed the importance of an education, the greater their motivation and subsequent achievement. Similarly, Fan and Williams (2010) found that parents’ reports of advising adolescents (e.g., helping their adolescent make plans for college) and communication of educational aspirations were positively linked to both math and English intrinsic motivation.

These two studies provided evidence for a link between academic socialization and motivation but were limited by sample demographics (primarily White/Caucasian; Marchant et al. 2001) and operationalization of motivation (a focus on subject-specific motivation; Fan and Williams 2010). These two studies also focused solely on linear associations between parental involvement and adolescent intrinsic motivation. The scant amount of research investigating academic socialization is concerning given the increased importance of academic socialization as an indirect involvement strategy that may best meet the developmental needs of adolescents (Hill and Tyson 2009). Therefore, due to these study limitations and in response to a call to researchers to further examine these associations (Fan and Williams 2010), the present study analyzed nonlinear links between academic socialization and adolescents’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Examining nonlinear associations is particularly important to investigate thresholds of parental involvement, as higher levels of involvement may not always benefit adolescents because it can undermine adolescents’ growing need for an autonomy-supportive environment (Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler 1995; Ryan and Deci 2000b).

The Current Study

The current study sought to address the noted gaps in literature and enhance the understanding of the nature of the associations among home-based involvement, academic socialization, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation during early adolescence. Grounded in theory and empirical research on parental involvement and academic motivation, we hypothesized that the relation between involvement and motivation would be nonlinear. More specifically, we expected the positive association between home-based involvement and intrinsic motivation to be attenuated at high levels of involvement. We also expected the positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation to be attenuated at high levels of involvement. Given the limited previous research on the association between parental involvement and extrinsic motivation, no a priori hypotheses were made regarding these associations.

The current study utilized adolescent race, parent education level, and perceived academic competence as control variables, as previous studies have found differences in parent involvement by adolescent race and socioeconomic status (Hill et al. 2004) and that adolescents’ prior academic performance may predict parent involvement (Pomerantz et al. 2007). Further, scholars have noted that links between parental involvement and adolescent outcomes may be reporter dependent, as parent and adolescent reports are not always consistent (DePlanty et al. 2007; Hill and Taylor 2004). Therefore, in this study, parent and adolescent reports of involvement were included. Finally, parent–adolescent relationship quality was included as a control variable, given the potential implications of relationship quality for adolescent motivational outcomes (Gonzalez-DeHass et al. 2005; Lowe and Dotterer, 2013).

Method

Participants

Participants were adolescents (N = 150) from a public, title I (72 % of students qualified for free lunch), Midwestern urban middle school (56 % female). Fifty-three adolescents were in sixth grade (35 % of the sample), 62 were in seventh grade (41 %), and 35 were in eighth grade (24 %). Fifty-seven percent of participants were Black or African American, 19 % were multiracial, 18 % were White/Caucasian, 5 % were Hispanic or Latino, and 1 % were Asian. Participants in this sample largely reflected the demographic makeup of the entire school, with the exception of this sample having a slightly higher percentage of White/Caucasian and mixed race adolescents and lower percentage of Hispanic or Latino adolescents (National Center for Education Statistics 2010). One third of the parent participants reported their education level as a college degree or higher, 43 % indicated some college, and 25 % indicated high school diploma or less. Most of the parent participants identified as the adolescent’s mother (87 %), whereas 11 % identified as the father. Just over half of parent participants were married (55 %).

Procedure

Data for this study were drawn from a larger study investigating school and family experiences of urban youth. After receiving Purdue University IRB approval, participants were recruited during the middle school’s registration and via letters mailed to family’s homes. Following parental consent and adolescent assent, adolescents completed a self-report survey in the school cafeteria during a free class period. Adolescents who were absent from school on the day of data collection were mailed a survey. Parents completed a survey via telephone, the internet, or a paper and pencil survey returned via mail.

Measures

Intrinsic Motivation

Adolescents completed a 17-item intrinsic motivation scale (Lepper et al. 2005) that has been used in previous research with early adolescents to measure intrinsic motivation (Corpus et al. 2009). Lepper and colleagues (2005) provided evidence of the reliability and construct validity of this measure via test–retest data collection, item-whole correlation analyses, and factor analysis. They also provided evidence of criterion validity, as scores were positively correlated with teacher ratings of intrinsic motivation. Adolescents responded using a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = always) to items such as “I like hard work because it’s a challenge” and “I ask questions in class because I want to learn new things.” Mean scores were created such that higher scores indicated more intrinsic motivation (α = 0.89).

Extrinsic Motivation

Adolescents completed a six-item extrinsic motivation scale that specifically addressed students’ preference for easy work. This measure has also been used to measure extrinsic motivation in previous work (Corpus et al. 2009; Lepper et al. 2005). As described above, Lepper and colleagues (2005) provided evidence of the reliability and construct validity of this measure, and participant’s scores were negatively correlated with teacher ratings of intrinsic motivation, which was evidence of criterion validity. Adolescents responded using a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = always) to items such as “I like to stick to the assignments which are pretty easy to do” and “I learn only what I have to pass my classes in school.” Mean scores were created such that higher scores indicated more extrinsic motivation (α = 0.78).

Home-Based Involvement

Home-based involvement was measured with six items that have been used extensively in previous research (Steinberg, Brown, and Dornbusch, 1992). This measure has an established alpha reliability of 0.74 and has been used with multiethnic samples (Steinberg et al. 1992; Crosnoe 2001). Adolescents reported on parents’ use of home-based involvement strategies on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 3 = always) and reported on mothers and fathers involvement separately. A sample item was “Helps me with my schoolwork.” Adolescent reports of mother and father involvement were significantly correlated (r = 0.49, p < 0.001), so a total home-based parental involvement score was calculated by averaging the two scores such that higher scores indicated more home-based parental involvement (α = 0.86). Parent report of home-based involvement was measured using a single item from a shortened version of the same measure: “I help with homework.” Wording was revised to reflect the parent perspective. Parents responded using a 3-point scale (1 = never, 3 = always).

Academic Socialization

Academic socialization was measured with items adapted from Murdock’s (1999) Economic Value of Education scale to assess adolescents’ reports of parents’ socialization of educational values. An index score for this measure was created with items from two subscales—benefits of education and limitations of education, which has been done in previous research (Colón and Sánchez 2010). Murdock (1999) found that items in these subscales form stable factors and that scores have logical correlations with school effort and behavior, thus demonstrating criterion validity. This scale served as a measure of academic socialization by assessing the extent to which parents communicate the value or utility of an education, a key aspect of academic socialization (Hill and Tyson 2009). Using a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), adolescents responded to eight items such as “My parents tell me that many of the things I learn in school will be useful in the future.” A mean score was calculated such that higher scores indicated more academic socialization reported by adolescents (α = 0.79). Parents responded to the same 8-item, 5-point scale survey that was reworded to reflect the parent perspective (e.g., “I tell my child that many of the things he/she learns in school will be useful in the future.”). A mean score was calculated such that higher values indicated more academic socialization reported by parents (α = 0.78).

Parent-Adolescent Relationship Quality

Adolescents reported on their mother’s and father’s warmth and acceptance using a shortened 8-item version of the Child’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI). This scale has demonstrated reliability and construct validity (as assessed via factor analysis and coefficients of congruence; Schwarz et al. 1985). An example item was “My mother/father is able to make me feel better when I am upset.” Reports of relationship quality for mothers and fathers were significantly correlated (r = 0.32, p < 0.001). A mean score was calculated such that higher scores indicated higher levels of parental warmth/acceptance (α = 0.91).

Perceived Academic Competence

A scale adapted from Jacobs et al. (2002) that has demonstrated reliability (with Chronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.76 to 0.93) and construct validity (via factor analysis; Eccles et al. 1993) was used to assess adolescents’ perceived academic competence. Perceived academic competence was calculated by averaging the sums of adolescents’ reports of perceived English and math competence during the spring semester (α = 0.77). Adolescents responded to five items such as “How good at math/reading are you?” using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all good, 7 = very good).

Demographic Variables

Adolescents reported their gender (male = 0; female = 1) and race. Given the small number of adolescents identifying as American Indian, Asian American, and Hispanic or Latino, adolescent race was transformed into two dummy code variables (White = 0): One dummy code represented African American adolescents, the second was labeled “other,” which represented adolescents identifying as any of the other three race/ethnicities. Parents reported their education level ranging from “high school degree” (1) to “advanced degrees such as MS, MD, or Ph. D.” (5).

Results

Analytic Strategy

Hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to examine nonlinear associations between parental involvement and academic outcomes. Following the strategies outlined by Aiken and West (1991), hierarchical regression models were used to examine the nonlinear relation between each type of parental involvement (home-based involvement and academic socialization) as it related to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in separate models. Home-based involvement and academic socialization variables were centered at their means (X), and quadratic (X 2) and cubic (X 3) terms were created from the centered variables. In step 1, control variables were entered (adolescent race and gender, parent education level, relationship quality, and parent report of involvement). In step 2, adolescents’ reports of parental involvement (X) were entered, and in step 3, the quadratic involvement variable (X 2) was added. In step 4, the cubic involvement variable (X 3) was added to determine the best fit for modeling the nonlinear association (Aiken and West 1991). The statistically significant polynomial coefficients were examined to characterize the shape of the curves that depicted the nonlinear association between involvement and motivation.

Further analyses examined the assumptions of ordinary least squares regression in each model; assumptions that could be tested were met in each of the models. DF beta and DF fit values were calculated to determine if there were any data points with undue influence. Data points were examined for intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation models separately and were considered to have undue influence if they surpassed critical values for both DF beta (critical value 0.16) and DF fits (critical value 0.52) (Belsley et al. 1980). There were no cases with consistent undue influence based on DF beta and DF fit values across all predictors.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 includes descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables. Adolescents reported relatively high levels of both home-based involvement and academic socialization. Parents reported a higher average level of academic socialization compared to adolescents, t(149) = 3.68, p < 0.001, but there were no statistically significant reporter differences in home-based involvement. Parent reports of academic socialization and home-based involvement were not significantly correlated with intrinsic motivation or extrinsic motivation. Adolescent reports of both types of involvement were significantly correlated with intrinsic motivation in the expected direction but neither was significantly correlated with extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation were significantly negatively correlated. Analyses examining group differences in motivation revealed that boys and girls did not differ in their mean levels of intrinsic or extrinsic motivation. Additionally, there were no significant race differences in intrinsic or extrinsic motivation.

How Is Home-Based Involvement Related to Motivation?

Intrinsic Motivation

In step 1, the set of control variables predicted intrinsic motivation, F(7, 142) = 9.55, p < 0.001. However, perceived academic competence was the only control variable that was significantly associated with intrinsic motivation, β = 0.48, p < 0.001, such that a 1-unit increase in academic competence (on a scale from 1 to 35) was associated with a 0.08-unit increase in intrinsic motivation (on a scale from 1 to 5). The linear association (step 2) between adolescent reports of home-based involvement and intrinsic motivation was not significant. The nonlinear quadratic and cubic effects of home-based involvement (steps 3 and 4) also were not significantly related to intrinsic motivation (see Table 2).

Extrinsic Motivation

The control variables (step 1) were significant predictors of extrinsic motivation, F(7, 142) = 2.36, p < 0.05. Perceived academic competence was negatively associated with extrinsic motivation, β = −0.19, p < 0.05, such that a 1-unit increase in academic competence was associated with a 0.04-unit decrease in extrinsic motivation (on a scale from 1 to 5). The linear association (step 2) between home-based involvement and extrinsic motivation was not significant. The nonlinear quadratic and cubic effects of home-based involvement (steps 3 and 4) also were not significantly related to extrinsic motivation (see Table 3).

How Is Academic Socialization Related to Motivation?

Intrinsic Motivation

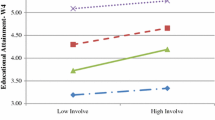

In step 1, control variables predicted intrinsic motivation, F(7, 142) = 9.79, p < 0.001. Perceived academic competence was the only control variable significantly associated with intrinsic motivation, β = 0.49, p < 0.001, such that a 1-unit increase in academic competence was associated with a 0.08-unit increase in intrinsic motivation. As can be seen in Table 4, the linear association (step 2) between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation was not significant. There was a significant negative nonlinear quadratic relation (step 3) between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation after controlling for race, gender, relationship quality, perceived academic competence, and parent report of academic socialization. There was also a significant negative nonlinear cubic relation (step 4) between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation. These results indicate that the positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation was attenuated at moderate levels of academic socialization and became negative at high levels of academic socialization. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation was weakened at high levels of academic socialization and resulted in low levels of intrinsic motivation.

Extrinsic Motivation

The control variables were significant predictors of extrinsic motivation, F(7, 142) = 2.38, p < 0.05. Perceived academic competence was negatively associated with extrinsic motivation, β = −0.21, p < 0.01, such that a 1-unit increase in academic competence was associated with a 0.04-unit decrease in extrinsic motivation. The linear association (step 2) between academic socialization and extrinsic motivation was not significant nor was the quadratic association (step 3). There was a significant nonlinear positive cubic relation (step 4) between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation after controlling for race, gender, relationship quality, perceived academic competence, and parent report of academic socialization (see Table 5). As can be seen in Fig. 2, there was no association between academic socialization and extrinsic motivation at low and moderate levels of academic socialization, but a strong positive association at high levels of academic socialization.

Discussion

Informed by theories of parental involvement and self-determination theory, the present study investigated the nature of parental involvement and its links to academic motivation during middle school. Previous literature has offered limited, mixed findings regarding the links between different types and levels of parental involvement and academic motivation, prompting the investigation of potential nonlinear associations among home-based involvement, academic socialization, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation. Overall, findings from this study indicated that home-based involvement was not associated with intrinsic or extrinsic motivation but that academic socialization was linked to both. More specifically, the associations between academic socialization and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation were nonlinear, indicating a decrease in intrinsic motivation and increase in extrinsic motivation at high levels of academic socialization. These findings offer unique evidence regarding the intended benefits of parental involvement for adolescents’ motivation.

Contrary to our hypotheses, home-based involvement was not associated with intrinsic or extrinsic motivation. These findings were surprising given that previous studies have shown associations between home-based involvement and both types of motivation (e.g., Ginsburg and Bronstein 1993; Spera 2006). These nonsignificant findings may indicate that finer distinctions should be made in terms of home-based involvement measures. Some scholars have noted that particular aspects of home-based involvement may be differentially associated with adolescent outcomes (Hill and Tyson 2009). For example, homework help may affect adolescent motivation differently than other aspects of home-based involvement, such as parents’ knowledge about school performance or problems at school. Future studies should further examine these distinctions in order to better understand how different facets of home-based involvement may be associated with motivational outcomes. Further, home-based involvement was positively correlated with intrinsic motivation but was not significantly related to intrinsic motivation in the full regression model. It may be the case that home-based involvement has limited unique variance with intrinsic motivation beyond the other factors in the model, or the sample size of this study may have limited power such that small effect sizes were not able to be detected as statistically significant.

Results regarding academic socialization and intrinsic motivation supported our hypotheses. The positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation was attenuated at high levels of academic socialization. This finding advances our understanding of the association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation, as previous literature has focused primarily on linear associations. This finding supports theoretical perspectives suggesting that more involvement may not always benefit adolescents (e.g., Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler 1995; Pomerantz et al. 2007). Future studies should explore the mechanisms that explain the nonlinear association between parental involvement and motivation. For example, as suggested by self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2000b), high levels of academic socialization may undermine adolescent autonomy, which, in turn, decreases intrinsic motivation.

A nonlinear effect was also significant for academic socialization and extrinsic motivation. There was no association between academic socialization and extrinsic motivation at low and moderate levels of academic socialization, but a strong positive association was statistically significant at high levels of academic socialization. Given the lack of previous empirical evidence linking academic socialization to extrinsic motivation, these findings contribute to our understanding of the potential drawbacks of high levels of academic socialization, as greater levels of extrinsic motivation have been linked to lower grades, standardized test scores, and cognitive engagement (Lepper et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2006). Future studies should further investigate this nonlinear association, given that these findings qualify what scholars have previously noted: that academic socialization may be the most pervasive and beneficial form of parental involvement during adolescence (Hill and Tyson 2009; Hoover-Dempsey et al. 2009). Our results temper this general conclusion by suggesting that it may only be true for certain levels of academic socialization during early adolescence.

Finally, though not intended as a focus of this study, findings interestingly showed that all of the factors included in these models (adolescent and parent demographic factors, parental relationship quality, perceived academic competence, and parental involvement) were better predictors of intrinsic motivation than extrinsic motivation. For home-based involvement, 33 % of variance in intrinsic motivation was explained by the predictors, compared to just 11 % of variance in extrinsic motivation, and for academic socialization, predictors explained 36 % of variance in intrinsic motivation and just 13 % of variance in extrinsic motivation. These differences provide further evidence that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation should be examined as separate constructs, as the same factors that accounted for a sizable amount of variance in intrinsic motivation did not account for as much variance in extrinsic motivation in our study. These differences also suggest that family factors such as those included in these analyses (e.g., parental involvement and parent–adolescent relationship quality) may not be the best predictors of adolescents’ extrinsic motivation, as they only accounted for 11 % of its variance. Future studies should investigate other contexts such as peer relationships, classroom environment, and school culture, which may better explain adolescents’ extrinsic academic motivation.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study provides novel insights into the associations between two types of parental involvement and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among adolescents, but there are several limitations to mention. First, this study used a correlational, cross-sectional design, which prohibits the interpretation of causal relations. This study design also limits the ability to fully investigate potential adolescent-driven associations between involvement and outcomes, particularly if these associations are dynamic and unfold over time. This study also combined adolescents’ reports of mothers’ and fathers’ home-based involvement in order to create the best match between reports of each type of involvement (data for academic socialization were not collected for mothers and fathers separately). While these home-based involvement measures were significantly correlated, future studies should separate mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices to investigate potential differences in parents’ educational involvement strategies and how they are linked to adolescent outcomes (Ginsburg and Bronstein 1993). Additionally, this study had a relatively small sample size. While there was adequate power to detect the moderate effect size of academic socialization, there was limited power to detect the small effect size of home-based involvement. A power analysis indicated that a sample size around 175 would be necessary to detect small effect sizes at a 0.05 probability level and statistical power of 0.80 (Cohen 1988). Future studies with larger samples may better detect these small but meaningful associations. Lastly, a strength of this study was the inclusion of parent reports of involvement in an effort to tease apart reporter differences noted in previous studies (i.e., parent vs adolescent report). However, parent reports of home-based involvement were measured using a single item, and most measures in this study were self-reported by adolescents. Future studies should incorporate more detailed measures for gauging parents’ perception of their home-based involvement, as well as additional measures of these constructs to avoid potential mono-reporter bias.

Despite these limitations, this study provides new insight into the associations between parental involvement and academic motivation for adolescents by examining the possible nonlinear associations between parental involvement (i.e., home-based involvement and academic socialization) and adolescent academic motivation (i.e., intrinsic and extrinsic motivation). Few previous studies have investigated home-based involvement and academic socialization as they relate to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the same sample; nonlinear associations have also not previously been analyzed. Following, findings from this study have implications regarding the nature of parental involvement during middle school for future research, programs, and policy. The nonsignificant associations between home-based involvement and motivation should prompt future researchers to consider more fine-grained distinctions in types of home-based involvement to better understand how these types of involvement are associated with motivation, if at all, during adolescence. It is also important for future studies to consider nonlinear associations. This study provides new evidence that the positive association between academic socialization and intrinsic motivation can be attenuated at high levels of involvement and that high levels of academic socialization are associated with increased extrinsic motivation during middle school. School programs and policies aiming to increase parents’ academic socialization should do so with care; simply encouraging parents to be more involved may not ultimately benefit adolescents and may in fact lead to diminishing returns.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Archibald, A. B., Graber, J. A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Pubertal processes and physiological growth in adolescence. In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 24–47). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Velsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Casey, B. J., Getz, S., & Galvan, A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review, 28, 62–77. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.003.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colón, Y., & Sánchez, B. (2010). Explaining the gender disparity in Latino youth’s education: acculturation and economic value of education. Urban Education, 45, 252–273. doi:10.1177/0042085908322688.

Corpus, J. H., McClintic-Gilbert, M. S., & Hayenga, A. O. (2009). Within-year changes in children’s intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations: contextual predictors and academic outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34, 154–166. doi:10.1016/j.cedpysch.2009.01.001.

Crosnoe, R. (2001). Academic orientation and parental involvement in education during high school. Sociology of Education, 74, 210–230. doi:10.2307/2673275.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: the self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26, 325–346. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2603&4_6.

DePlanty, J., Coulter-Kern, R., & Duchane, K. A. (2007). Perceptions of parent involvement in academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 100, 361–368. doi:10.3200/JOER.100.6.361-368.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1996). Family involvement in children’s and adolescents’ schooling. In A. Booth & J. F. Dunn (Eds.), Family-school links: how do they affect educational outcomes? (pp. 3–34). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 404–434). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R. D., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self‐and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64, 830–847. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02946.x.

Epstein, J. L. (2001). School, family, and community partnerships: preparing educators and improving schools. Boulder: Westview Press.

Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self‐efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30, 53–74. doi:10.1080/01443410903353302.

Ginsburg, G. S., & Bronstein, P. (1993). Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance. Child Development, 64, 1461–1474. doi:10.2307/1131546.

Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., Willems, P. P., & Holbein, M. F. D. (2005). Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 17, 99–123. doi:10.1007/s10648-3949-7.

Gottfried, A. E. (1985). Academic intrinsic motivation in elementary and junior high school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 631–645. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.77.6.631.

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: a longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 3–13. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.3.

Hayenga, A. O., & Corpus, J. H. (2010). Profiles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: A person-centered approach to motivation and achievement in middle school. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 371–383. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9181-x.

Hill, N. E., & Chao, R. K. (2009). Background in theory, practice, and policy. In N. E. Hill & R. K. Chao (Eds.), Families, schools, and the adolescent (pp. 1–15). New York: Teachers College Press.

Hill, N. E., & Taylor, L. C. (2004). Parental school involvement and children’s academic achievement pragmatics and issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 161–164. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00298.x.

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: a meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45, 740–763. doi:10.1037/a0015362.

Hill, N. E., Castellino, D. R., Lansford, J. E., Nowlin, P., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development, 75, 1491–1509. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x.

Hoover-Dempsey, K., & Sandler, H. (1995). Parental involvement in children’s education: why does it make a difference. Teachers College Record, 97, 310–331.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Ice, C. L., & Whitaker, M. C. (2009). We’re way past reading together: why and how parental involvement in adolescence makes sense. In N. E. Hill & R. K. Chao (Eds.), Families, schools, and the adolescent (pp. 19–36). New York: Teachers College Press.

Jacobs, J. E., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Changes in children’s self‐competence and values: gender and domain differences across grades one through twelve. Child Development, 73, 509–527. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00421.

Jeynes, W. H. (2003). A meta-analysis the effects of parental involvement on minority children’s academic achievement. Education and Urban Society, 35, 202–218. doi:10.1177/0013124502239392.

Karbach, J., Gottschling, J., Spengler, M., Hegewald, K., & Spinath, F. M. (2013). Parental involvement and general cognitive ability as predictors of domain-specific academic achievement in early adolescence. Learning and Instruction, 23, 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.09.004.

Lepper, M. R., Corpus, J. H., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 184–196. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.184.

Lowe, K., & Dotterer, A. M. (2013). Parental monitoring, parental warmth, and minority youths’ academic outcomes: Exploring the integrative model of parenting. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1413–1425. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9934-4.

Marchant, G. J., Paulson, S. E., & Rothlisberg, B. A. (2001). Relations of middle school students’ perceptions of family and school contexts with academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools, 38, 505–519. doi:10.1002/pits.1039.

Murdock, T. B. (1999). The social context of risk: status and motivational predictors of alienation in middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 62–75. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.62.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2010). CCD public school data 2010–2011. Washington: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) (2002) Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-110, § 115, Stat. 1425.

Pomerantz, E. M., Moorman, E. A., & Litwack, S. D. (2007). The how, whom, and why of parents’ involvement in children’s academic lives: more is not always better. Review of Educational Research, 77, 373–410. doi:10.3102/00346530305567.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. R. (2008). Motivation in education: theory, research and applications. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education Inc.

Schwarz, J. C., Barton-Henry, M. L., & Pruzinsky, T. (1985). Assessing child-rearing behavior: a comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development, 56, 462–479. doi:10.2307/1129734.

Singh, K., Bickley, P. G., Trivette, P., Keith, T. Z., Keith, P. B., & Anderson, E. (1995). The effects of four components of parental involvement on eighth-grade student achievement: structural analysis of NELS-88 data. School Psychology Review, 24, 299–317.

Spera, C. (2006). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental goals, practices, and styles in relation to their motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 456–490. doi:10.1177/0272431606291940.

Steinberg, L., Dornbusch, S. M., & Brown, B. B. (1992). Ethnic differences in adolescent achievement: An ecological perspective. American Psychologist, 47, 723. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.6.723.

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling, N. (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63, 1266–1281. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x.

Walker, C. O., Greene, B. A., & Mansell, R. A. (2006). Identification with academics, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy as predictors of cognitive engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 16, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2005.06.004.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Abery, B. H., Mithaug, D. E., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2003). Theory in self-determination: foundation for educational practice. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, Publisher Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wehrspann, E., Dotterer, A.M. & Lowe, K. The Nature of Parental Involvement in Middle School: Examining Nonlinear Associations. Contemp School Psychol 20, 193–204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0071-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0071-9