Abstract

Prevailing approaches to the structural challenges of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) tend to be monolithic and skewed towards CSR at the organisational level. Albeit, mirroring CSR at the organisational level with activities of practitioners at the social level can offer new reflexive approaches for identifying capabilities for and understanding thresholds of social learning. This chapter maps out how identity perspectives to CSR can offer new approaches for surfacing emergent properties inherent in the uptake of CSR institutionally and in practice. The chapter also presents an overview of the interplay between structure and agency (prescribed and actual CSR practices) and its underlying instrumental role for illuminating systemic factors which perpetuate such capabilities and thresholds. Using a morphogenetic theory of change, the chapter offers a framework for approaching CSR-based corporate identity. Empirical evidence from the applied framework is thereafter presented, in the context of the agro-processing industry based on a content analysis of annual reports, in-depth-interview data generated from four sustainability managers and corporate communication officers and the practices of extension and Local Economic Development (LED) officers. The framework demonstrates that companies with a disintegrated CSR identity inherently have more capacity to be change agents. Similarly, a strong corporate heritage identity is not indicative of a reciprocal link between espoused values and activity. Conversely, an enduring corporate heritage identity may not necessarily be improvisatory for social learning. In conclusion, the chapter gives an overview of a taxonomy of agential capabilities and associated cognitive resources inherent in the interaction between structural-cultural and personal emergent properties, which can initiate the positioning of social learning at the forefront of organisational deliberations.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate heritage identity

- Corporate social responsibility

- Structure

- Agency

- Local economic development

- Social learning

1 Introduction

Increasing interests in the sustainability of business practices have positioned CSR at the forefront of corporate deliberations. This phenomenon has influenced ad hoc adaptation of global practices to national sustainability ratings such as the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE)/Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) responsible investment index. The FTSE/JSE appraises the sustainability practices of companies in South Africa using Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) practices and performance metrics based on data available in the public domain. Nevertheless, reliance on third-party frameworks in the appraisal of CSR impacts resonates with what Elkington (2018) refers to as an ‘alibi for inaction’. Increasing pressure on corporate accountability can equally exacerbate the misfit between espoused CSR and its impacts (Ijabadeniyi 2018).

Moreover, the aftermath of the history of social exclusion of minority groups in South Africa on the triple dilemma of unemployment, poverty and inequality (Ndhlovu 2011) demonstrates the importance of the mindfulness of historical structural conditioning on practices. The reinterpretation of history can however offer an extended notion of the past which can give an expanded and new meaning different from the past (Burghausen and Balmer 2014), which if approached in line with inherent capabilities in organisational structures and activities, can illuminate thresholds of the power of the agent to enable social learning (Sannino et al. 2016).

From a developmental CSR viewpoint, careful consideration of how organisational practices feed into governance and illuminate internal and external constraining and enabling factors (Mapitsa and Khumalo 2018) could enrich our understanding of the capabilities of corporate heritage identity to achieve desired/optimum social identity. CSR in Africa is reckoned to be driven by underlying cultural values of sharing and communal harmony (Dartey-Baah and Amponsah-Tawiah 2011). The argument here is not on fostering normative approaches for moving the sustainability agenda forward, but on illuminating and understanding the causal factors which underpin intrinsic multi-level organisational relations, emergent properties (Elder-Vass 2010) and its associated transformative agency (Sannino et al. 2016).

Given the volatility of organisational behaviour in response to institutional stimuli, there are tendencies for deviations from the uptake of legitimately sanctioned practices. Organisational behaviour embedded in a communicative approach which is responsive to changing societal expectations and needs has been advocated for legitimising practices (Deegan 2002). From a corporate citizenship viewpoint, ongoing communication is equally instrumental for sensitively engaging in public deliberations (Matten et al. 2003). It is of utmost interest how learning pathways for social change can be derived from ensuing engagement in public deliberations and interactions inherent in the pursuit of legitimacy. It is equally germane how cognitively situated legitimate practices can be activated to co-create and amplify social leadership, through mindfulness of the identity perspectives of CSR.

2 Identity Perspectives of CSR and Social Learning

Corporate identity encompasses the soul, voice and mind of the organisation (Balmer and Soenen 1999). History, culture and strategy, therefore, form an integral part of the corporate identity portfolio (Balmer and Greyser 2002). Management’s vision and organisational core values, equally play an important role in the approach to CSR. The alignment of CSR into corporate mission and values (Marcus and Anderson 2006) varies across countries and industries, so do approaches to CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). The attributes of a CSR-based corporate identity, as conceived by internal stakeholders, can reveal patterns of historical structural conditioning in practices. For example, Carmeli et al. (2007) found that organisational identity mediates the relationship between CSR and its outcomes, which reveals the pivotal role of organisational culture on the manifestations of CSR-based corporate identity. Mudrack (2007) reports that values are the antecedents of management commitment to CSR, namely, values which relate to supervisor commitment to ethics (Muller and Kolk 2010), organisational pride (Jones 2010) and the sensitivity of managers to equity (Mudrack 2007). Nevertheless, some organisational values have an opportunistic CSR undertone. This notion is supported by Sharma (2000) who argues that CSR engagement can be motivated by the quest for reputational capital. Intangible descriptors such as human capital and prevailing CSR culture can however reveal underlying motives (Surroca et al. 2010).

The extent to which individual values of organisational members are congruent with organisational values (Bansal 2003), and the congruence between individual values and espoused CSR mandate (Mudrack 2007) can also suggest patterns of a CSR identity. Psychological identity traits (Aguilera et al. 2007), such as the extent to which employees are driven by motives other than self-interest (Rupp et al. 2011a), have also been reported to drive CSR engagement. Similarly, Rupp et al. (2011b) advanced that employee autonomy, relations and competence also inform CSR engagement. Reagan et al. (2015) add that higher levels of Leader–Member Exchange (LMX) positively influence valence of donating. In other words, cognitive and motivational attachments to CSR were influenced by the quality of relationship between managers and team members.

Instances of where corporate identity components, which as a consequence relates to communicated, conceived ideal and desired identities, have reinforced CSR engagement have also been reported in the literature. A higher degree of public contact, management emphasis on CSR values (De Luque et al. 2008) and firm size (Godfrey et al. 2009) were reported to harness CSR engagement. Strategic alliances, organisational approach to CSR and CSR communication approach have been reported to drive CSR engagement and outcomes. For example, Theuvsen et al. (2010) found that strategic group membership and the ability to move between groups, significantly influence CSR performance. The entrenchment of the four levels of social responsibilities, viz., social obligation, social responsibility, social impact and social responsiveness, identified by McDonald (2015), have also been reported to reinforce CSR engagement.

The prevalence of strong Future Time Reference (FTR) in CSR communication is an indication of socially irresponsible behaviour; the greater the separation placed between present and future events, the lesser a company’s affinity to social responsibility Blanding (2014). Conversely, companies which focus and act less on the future have altruistic motives for engaging in CSR. The exhibition of strong FTR in CSR communication could hamper the ability to espouse ethical behaviour (ibid). Moral silence, moral deafness and moral blindness, which relate to failure to talk about wrong practices, failure to recognise the moral implications of actions and failure to act on prevailing moral issues, have also been identified to impede ethical behaviour (Blundel et al. 2013).

Complexities in business environments and conflicting institutional forces have been identified as major external factors influencing the adoption of CSR practices, particularly in the context of multinational enterprises (Marano and Kostova 2016). The heterogeneity of institutional forces and exposure to CSR best practices positively influence the adoption of CSR practices (ibid). It is therefore, evident that corporate missions and values are instrumental for driving CSR engagement. It is equally important to contextualise our understanding of the drivers of CSR engagements (Dartey-Baah and Amponsah-Tawiah 2011) and the institutional factors which influence the outcomes of CSR corporate identity (Otubanjo 2012), revealing pathways for leveraging institutional legitimacy (Suchman 1995).

2.1 Balmer and Soenen’s AC2ID Test Framework: A Morphogenetic Approach

Balmer and Soenen (1999) offered the actual, communicated, conceived, ideal and desired (AC2ID) identity test framework as a benchmarking tool against which corporate identity management practices can be appraised, in response to the need to align multiple and conflicting organisational identities in practice. The framework appraises multiple facets of the organisation and provides learning pathways for leveraging long-term viability and social change. While the framework does not explicitly include CSR, it provides a foundation through which business ethics and organisational legitimacy can be reinforced.

The AC2ID test framework is a synthesis of the dimensions of corporate identity, which is a valuable tool for practitioners to detect and prevent potential deleterious corporate identity misalignments in practice, with the aim of ensuring a dynamic congruence between these identity types (Balmer and Greyser 2002). This framework highlights five vital identity types which ought to be aligned to foster sustainability (Balmer and Soenen 1999). These five identity types comprise the actual identity (what we really are), communicated identity (what we say we are), conceived identity (what we are seen to be), ideal identity (what we ought to be) and desired (what we wish to be) identity. The framework is a useful tool for assessing corporate identity vis-à-vis CSR management (Kleyn et al. 2012), as the core of the framework relates to organisational legitimacy (Suchman 1995).

The AC2ID test framework has been applied in different contexts and has revealed imminent identity misalignments relating to employee relations and customer relationship management (Balmer et al. 2009). For example, Powell et al. (2009) found misalignments between lower level employees’ perceptions of ethical actual and ideal identities as opposed to management’s ideal identity in the context of a major financial institution in the United Kingdom. Corporate identity management goes beyond a monolithic phenomenon, but rather one which is dialogical in nature (ibid). Efforts should, therefore, be geared towards bridging the gap between CSR reporting and reality, the practice of which can reveal inherent capabilities for actualising corporate rhetoric narratives.

The essence of corporate identity communication should not be about organisations regurgitating what is written in annual reports, which in most cases is targeted at conforming to regulations, but rather explaining the process involved in initiating and implementing what has been documented. This notion is supported by Tenbrunsel et al. (2000) who found that a conscientious approach to conforming to standards and certification could erode the humanness in CSR, which could result in CSR being a symbolic and cosmetic tool which serve to minimally comply with requirements. Similarly, Kleyn et al. (2012) contend that the reinforcement of a culture of ethics by top management, the conformity of corporate behaviour to mission, codes of ethics and functional standards play a crucial role in creating a strong ethical identity. Besides, emphasis should be placed on ideal identity which is optimum positioning (Balmer et al. 2009).

Organisational restructuring caused by mergers and acquisitions has also been reported to influence misalignments in identity types. For example, the BP-Amoco merger in 1998 resulted in a debacle which revealed the misalignment between BP’s post-merger environmentally friendly brand positioning; communicated identity and actual identity (Balmer et al. 2011). BP’s post-merger brand promise was at best aspirational in that its rhetoric fell short of reality. The BP case is reflective of the institutional challenges faced by many companies nowadays given the economic turbulence which makes companies more vulnerable to restructuring (ibid). Companies should, therefore, conduct pre-merger analysis to identify potential CSR identity compatibilities which can be used to create new and realistic CSR identities, with implications for change-oriented structural elaboration (Archer 2011).

Bravo et al. (2012) argue that organisations tend to create distinctive identities through CSR activities and to establish ethical and social values within their corporate statements and cultures. While this approach is influential for building competitive advantage, efforts should be geared towards building distinctive but congruent identities. This notion is evidenced by the findings reported in the branding strategy implemented in Bradford city, United Kingdom (Verbos et al. 2007). The findings of the study revealed the inconsistencies in the perceptions of the Bradford brand across various communities in the city which reveal a mismatch between actual and communicated identities.

Balmer (2009) further argues that a lack of alignment between key corporate-level concerns such as corporate identity, corporate image and reputation can be caused by institutional difficulties. Companies therefore, often use corporate philanthropy to redress corporate ills or misconduct. For example, Cadbury contributed its profit between 1902 and 1908 to charitable causes upon allegations of human rights abuse involving African slave labour (ibid). In a conceptual study which reviewed 102 books and book chapters and 588 journal articles, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) argue that institutional pressures, mainly from stakeholders, induce firms’ engagements in CSR. An investigation into ethical corporate identity based on a case study of one of the best practices in the South African manufacturing sector, South African Breweries Ltd (SAB), revealed that the company pragmatically reinforces ethical values amongst its employees which makes it a good example of a company with a strong ethical identity through its ethos of social connectedness and responsiveness (Kleyn et al. 2012).

3 Corporate Identity Management

The ability of management to incorporate a CSR culture into the corporate identity mixes namely, soul, mind and voice of an organisation (Powell 2011), coupled with the dynamic integration of the interests of contingent stakeholders (Kohli and Jaworski 1990), can be instrumental for fostering social change. Fundamental to the management of corporate identity programmes is Balmer’s AC2ID test framework (Balmer et al. 2007). While the framework comprises actual, communicated, conceived, ideal and desired identities (Balmer 2007), the complexities eminent in the formation of corporate identity (Cornelissen 2014) as well as the influence of institutional and environmental factors in which companies operate could influence the formation of a CSR-based corporate identity (Balmer and Greyser 2002). Balmer’s AC2ID test framework addressed the gaps eminent in previously advanced corporate identity frameworks such as the corporate identity mix by Birkigt and Stadler (1986) and Balmer and Soenen (1997), based on the need to account for the multifaceted and evolving nature of corporate identity. While the framework raises a fundamental issue which draws attention to the interconnectedness between the ideal identity of the organisation, capabilities, social, economic, political and technological environment of the organisation, the framework fails to acknowledge the overarching role of CSR, as opposed to a focus on merely the ethical dimension of CSR in a subsequent contribution relating to the management of corporate identity programmes (Balmer et al. 2007). Given that the framework aims at corporate sustainability, it was deemed fit to incorporate CSR in organisational DNA (Otubanjo 2012), which necessitated an extension of the framework to account for the evaluation of a CSR-based corporate identity profile as explicated in Table 8.1.

In line with the adapted Balmer’s AC2ID test framework, Archer’s morphogenetic theory of change is foregrounded on the processes through which social change can occur over time (T1–T4, with T1 being Time 1, and T4 being Time 4), via structural conditionings (at T1), social interactions (T2–T3) and structural elaboration (at T4) (Archer 1995). Similarly, actual identity explicates the parameters through which structural conditionings can occur, communicated and conceived identity can reveal the mechanisms involved in the process of social interactions. The components of ideal and desired identity can signal possible structural elaboration (see Table 8.1).

While acknowledging the importance of ensuring congruence between the identity types advanced by the Balmer’s AC2ID test framework, inherent systemic factors which threaten organisational legitimacy (Nazari et al. 2012), can equally hamper the positioning of CSR for sustainable development. Intrinsic CSR factors can mitigate against the ability of a company to approach CSR from a value-driven viewpoint, given institutional complexities (Hildebrand et al. 2011).

Corporate rhetoric matches corporate behaviour when CSR is incorporated into business models. However, institutional and environmental factors which stem from corporate identity traits such as company history, structure and strategy (Balmer and Greyser 2002) can hamper the integration of CSR into business models. Given this typology, it is apparent that the ability of companies’ to implement value-driven CSR initiatives depends on organisational behaviour towards CSR. Since the main goal of corporates is value creation (Hildebrand et al. 2011), the extent to which contextualised value-driven CSR initiatives is integrated into overall corporate strategy is pivotal for its optimisation.

While the core foundations of business have historically been built around the ‘spirit of capitalism’, which is centred on value creation for shareholders, the increase in the depletion of economic, social and environmental values resulting from business operations is gradually increasing awareness of responsible or irresponsible business practices (Kibert et al. 2012), which has also made marketing claims vulnerable to criticisms of greenwashing (Powell et al. 2009). The extent to which organisations identify with responsible business practices which extend beyond mere compliance with sustainability legislations and reporting standards (Ionescu-Somers and Steger 2008) can reveal the morally conscious nature of its CSR corporate identity (Kleyn et al. 2012), as opposed to the use of CSR as a defensive strategy (Bruhn 2013). Higher stakeholder satisfaction and financial performance have been identified amongst organisations with a ‘strong’ morally conscious CSR corporate identity (ibid).

4 Conceptual Framework

Following Albert and Whetten (1985), core organisational attributes are those which give an organisation centrality, distinctiveness and endurance, which resonate with Archer’s (1995) conception of morphostasis in the morphogenetic cycle. This study is foregrounded on the notion that there is a dialectical relationship between structurally conditioned and unconditioned emergent practices. We refer to structurally conditioned influences on project administration as the ‘terrain of micro-level agency’ while structurally unconditioned practices are referred to as ‘terrain of macro-level agency’ and the dialectical relationship between the two terrains as the ‘terrain of meso-level agency’. The following question emerges as a result: Where are the emergent properties in the contested terrain of CSR learning situated? While taking cognisance of the significance of ideological underpinnings to resist change, it is anticipated that patterns across these taxonomies could inspire deliberations and reflexive practices geared towards enabling sustainable project outcomes and offer guidelines into how new practices can emerge. These taxonomies micro, meso and macro terrains are positioned as underlying mechanisms of change as they recognise the significance of diversity and social conditioning in the ability to bring about change in institutions. Since historically contingent social practices are ideologically motivated and collectively created (Jäger 2001), co-engaged deliberations and the ability to facilitate ongoing communicative processes and practices could gradually bring about desirable change.

Balmer and Burghausen have over the years contributed to the evolutionary and instrumental nature of the corporate heritage identity construct. Corporate identity is augmented when multiple identity roles in the present are symbolic of the past, present and future (Balmer 2013), reinterpreted when symbolic relevance to the past is extended to give a new meaning in the present and future (Burghausen and Balmer 2014), appropriated when organisational stakeholders actively accept the past as an inheritance in the present and legacy for the future (Balmer and Burghausen 2015) and valorised when organisations selectively and meaningfully harness the past for institutional value for the present and potential worth for the future (Balmer and Burghausen 2018). From this analogy, it follows that given historically contingent social practices (structural conditioning), the will of the agent inherently has emergent capabilities. There is therefore, room for the power of the agent to bring about change in highly contested terrains and complex social structures (Archer 1995).

Drawing on the morphogenetic theory of change, the methodological approach termed ‘analytical dualism’ helps to analytically identifyFootnote 1 personal, social and cultural emergent properties inherent in the critical realist dialectic of structure and agency (Archer 1995), which is foregrounded on how morphostasis and morphogenesis explicate the resistance and elaboration of an entity, respectively (Elder-Vass 2010). The morphogenetic model of change acknowledges that change is inherent in structural preconditions which is independent of an agent, but that agents are potentially capable of mobilising social networks and processes for change, in order to bring about structural elaboration. This may not happen, in which case Archer names this morphostasis. In line with Archer’s argument, this study seeks to understand forms of interactions in which structural causal powers interfere with agential activities and the emergent properties of agents.

The structure of an entity is multi-layered, and the recognition of its causal powers is dependent on interactions with other entities (Elder-Vass 2010). Communicative processes of social systems (i.e. organisations and their interactions) can shape and be shaped by historically contingent social practices, which can produce the criteria for transformation. A deeper understanding of the problems of interpretation and communication of historically contingent practices is a precondition for the development and functioning of complex societies (King and Thornhill 2003). Social change is at best rhetorical in contemporary organisations going through constant structural changes, the skill of the agent to influence structure is particularly relevant within organisations with oligopolistic powers (Whittington 2010). It then follows that there exist possibilities for multiple perspectives of the interpretation and implementation of the communicative processes inherent in historically contingent practices.

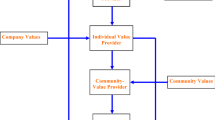

As Van Assche et al. (2014) notes, new structures are foregrounded in previous ones and generic concepts enable the reproduction of governance by interpreting differences between world construction and discourses. As such, structure plays a major role in governance. Porpora (2007) views emergent structure as being autonomous of the behaviour of the parts of the whole. Emergent properties, as opposed to the properties of its parts, are anticipated to most decisively explain the behaviour of ‘new wholes’. In other words, agents can independently exert influence on the outcome of emergent structures in governance, while taking cognisance of structural constraints on the autonomy and exercise of willpower. The effects of these constraints could most decisively be limited between T2 and T3 (meso-level agency) as shown in Fig. 8.1. The essence of synchronic (time-specific) emergence is its potential to explain the process through which an entity can have a causal impact on the world, over a diachronic period of time (Elder-Vass 2010). The causal powers of structure and agency in the context of CSR-based identity can, therefore, be understood along morphogenetic dimensions (see Fig. 8.1).

Adapted from Archer’s morphogenic framework (1995) and Balmer et al. (2007)

Towards a morphogenetic framework for CSR corporate Identity

To this end, this study takes a deeper look at the institutional embeddedness of the culture of CSR in the context of corporate identity and how much such culture is manifested in the practice of Local Economic Development (LED) projects. In other words, we aim to understand the mechanisms through which activity is institutionally situated to motivate environmentally conscious behaviour (Ellen et al. 1991).

5 Application of the Framework

The robust sugarcane industry in South Africa is positioned as a catalyst for economic development being a major source of livelihood for one million rural farmers, who are mostly located in the KwaZulu-Natal province (SASA 2017). The second-largest number of households involved in subsistence and small-scale farming is found in the KwaZulu-Natal province, after the Eastern Cape (StatsSA 2013). The inability of small-scale farmers to participate in modern agricultural value chains in South Africa (Von Loeper et al. 2016) is one of the key challenges to food security (FAO et al. 2010), amidst high unemployment, poverty and inequality rates (Babarinde 2009). Ironically, community-based interventions are not always designed to adequately address community development needs (Aucamp 2015). Multi-stakeholder LED projects in the agricultural sector have primarily failed due to design flaws and governance issues (James and Woodhouse 2017). It was, therefore, deemed fit to apply this framework in the context of LED projects targeted at farming cohorts in the Northern and Southern regions (North and South coasts) of KwaZulu-Natal, where the main factories of the two agro-processing companies included in this study are situated.

6 Methods

Archer (1995) advances that time (T1–T4) is an important determinant factor of change in the morphogenetic model on the account that change happens over time. Structural conditions precede social interactions at time 1 (T1), which are influential on the change that may occur through social interactions at time 2 (T2) and may then lead to subsequent structural elaboration from time 3 to 4 (T3–T4). The morphogenetic analysis was operationalized using the AC2ID test framework. Analysis at T1 was based on the attributes of Actual CSR identity which was supported by a content analysis of annual reports which assessed situated CSR-based corporate identity. Since the structure of an entity constitutes a number of layers, it was deemed fit to further assess situated institutional notions of CSR from an Industry Association perspective, which required consultation with the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Association.

The analysis of social interactions between T2 and T3 was based on insights drawn from conceived and communicated identity, alongside local consultations with extension officers, local economic development managers and farmers to assess the notions of CSR in practice. Context analysis of selected multi-stakeholder projects targeted at small-scale sugarcane farming was conducted based on the review of periodical reports. Personal in-depth interviews were also conducted with extension officers and managers at two sugar agro-processing companies, key informants at industry association bodies, an agricultural officer at the provincial department of agriculture and rural development as well as focus group discussions with small-scale sugarcane farmers in two sugarcane farming cohorts. Context analysis was necessary to assess socially constructed challenges facing multi-stakeholder LED projects at grass root level with the aim of identifying context-specific strategies designed to address such challenges, with particular attention paid to deviations from structural conditioning at T1.

The analysis thereafter involved the process of assessing changes which had occurred at T4 with reference to identifying emergent properties situated in the possible structural elaboration which could be evident through skills, knowledge, capital accumulation and demographic distribution. The analysis of structural elaboration at T4 was based on the components of the ideal and desired identity and supported with data obtained from involvement in an ongoing multi-stakeholder LED project which required consultations with project administrators and beneficiaries of the project. Project interventions constitute prior field-tested needs assessment in consultation with project beneficiaries to reflexively verify the effectiveness and contribution of interventions to projects. An iterative assessment was also conducted on the cognitive resources which the people in project interaction draw on when they produce project-related discourses in reports. A socio-economic impact assessment approach was thereafter employed to offer monitoring, evaluation and learning support for the project, which was targeted at small-scale farmers across four rural municipalities.

7 Surfacing Situated Social Learning Capabilities in Contested CSR Terrains

The antecedents and components of a CSR corporate identity are largely determined by organisational adeptness to localised ideologies of nurturing and exhibiting a morally conscious CSR profile. The findings generated in the analysis of structural conditioning (T1) reveal that actual identity serves as the antecedents of CSR corporate identity (see Figs. 8.2 and 8.3).

It was further observed that the attributes of communicated, conceived, ideal and desired identities constitute the components of CSR corporate identity profile. The core components of CSR corporate identity can be further divided into two, namely, core components and aspirational components which explicate social interactions (T2) and structural elaboration between T3 and T4, respectively (see Figs. 8.2 and 8.3).

8 Structure

Top-level managers deal more closely with wider institutional frameworks/legislation and will therefore, act more stringently to compliance for risk mitigation. Evident in this, are the structural-cultural emergent properties of power relations and resilient adherence to legislation. Lower level managers approach institutional frameworks/legislation narrowly and have the power to act in accordance to their level of knowledge/involvement. This points to the efficacy of personal emergent properties of agents, since all structures manifest temporal resistance through the conditioning of actions in context (Elder-Vass 2010).

Further analysis of structural conditioning reveals how antecedents can be demonstrated discursively. Table 8.2 gives a snapshot of a content analysis of annual reports which sought to assess meanings derived from repetitive reference to company name and use of institutionally and socially acceptable legitimation adjectives such as sustainability, stakeholder(s) and shareholder(s). It was found that repetitive reference to company name in discursive practices could have a narcissistic undertone, which could also be intentionally used to subliminally foster affinity. The prevalence of such phenomena could also be a manifestation of attributes of inherently resilient structures or an attempt to reinforce coherence and pride in heritage identity and ethos. Preference for the plural form of legitimation adjectives, which is this case in this study, could portray structurally conditioned dispositions towards fostering inclusivity and acceptance.

The ability to resiliently harness internal structures and power relations as structural-cultural emergent properties is largely influenced by company-specific factors arising from the diversity in corporate history, structure, culture, vision, mission and ethos. This points to the significance of deeply seated causal powers to bring about change. There were pronounced trends which indicate that the acquisition of the license to operate, sustainability of business practices and conformity with national and global best practices mediate the willingness and ability to enable emergent properties for change. In addition, the entrenchment of CSR corporate identity was indicative of the strength of corporate heritage identity while weak organisational structure was typically associated with disintegrated CSR corporate identity. A ‘strong’ corporate heritage identity may reinforce compliance and capitalistic approaches to CSR (Table 8.3).

9 Interaction

Espoused CSR at the organisational level is narrowly reflected in the social context as practitioners and project beneficiaries developed contextualised approaches to address prevailing issues, which imbibed the culture of self-reliance and entrepreneurship in the context of Company A and dependency in Company B. As Archer (1995) notes, agency exerts two independent influences between T2 and T3: temporal and directional influences. Practitioners generally prioritise the execution of business plans, irrespective of the applicability of project plans to prevailing beneficiary realities. Implicit assumptions such as the taken-for-granted and poverty-induced vulnerability of project beneficiaries leading to disguised social exclusion and dependency of small-scale farmers to project funding, constitute the main systemic factors hampering social change. There is room for improved capacity to unlearn the practices which result in project-induced socio-economic displacements and psycho-social impacts such as loss of entrepreneurial drive, rivalry and high dependency due in part to flawed project designs and project disruptions. There is evidence which suggests that the more the autonomy possessed by practitioners, the lower the tendency for project disruptions and shocks.

The capacity for social learning is moderated by the power vested in agency, which is mediated by intrinsic resilient capabilities. Practitioners are predisposed to enable social learning in practice even in the absence of espoused CSR legislation. This points to the significance of how ‘good’ CSR practices can be independent of legislation and espoused company ethos. As such, there is evidence which suggests that good CSR ethos are not necessarily always passed from top–bottom but also from bottom-top. The efficacy of prescriptive and obligatory CSR legislation to foster social learning and change at both the institutional and practice levels is limited, which emphasises the significance and capacity of agency to enable deliberations which encourage reflexivity.

For example, the vulnerability of project beneficiaries (in both North and South coasts) to dependency, project disruptions and project-induced displacements is moderated by the variety of land quality, accessibility to alternative sources of income and proximity to metropolitan cities. The magnitude of the negative impacts of these projects outweighs its contribution to the socio-economic development of small-scale farmers, especially in relation to the long-term return on investment and sustainability of these projects.

10 Structural Elaboration

Morphogenetic analysis can account for the gradual inception of new social possibilities and change facilitating factors between T2 and T4. Espoused CSR at the organisational level and practices at the social level are dependent on legitimation. This points to the lower tendencies for structural autonomy and conditioning to bring about change. The structural conditioning of a skewed focus on legitimation has influenced familiarity with and mastery of structure and social problems and ways of dealing superficially with deeply seated problems. Such structural conditions enable and reinforce a prescriptive culture towards practices.

The notion of a capitalisitic CSR approach could induce competitive organisational learning which consequently results in vulnerability to power struggles in the quest to remain competitive and profitable, and set the tone for another morphogenetic cycle. While such vulnerability could foster adeptness to the system in the short run, it could equally trigger self-reflexive practices in the long run. Continued co-engagement between actors could encourage the reciprocity of practices, which could foster social learning at both the organisational and social practice levels. Albeit, the ability of CSR corporate identity to foster social learning at the organisational level will largely be influenced by company-specific factors arising from the diversity in corporate history, structure, culture, vision, mission and ethos which could signal a new morphogenetic sequence (Archer 2011).

The emergent properties (rigorous and resilient policies and practices) inherent in the quest to acquire the license to operate, ensure sustainability of business practices and to conform to national and global best practices play a crucial role in the capacity to harness social learning for a new social reality. In addition, the entrenchment of CSR corporate identity was indicative of the strength of corporate heritage identity for company A, while weak organisational structure was typically associated with disintegrated CSR corporate identity in the context of company B.

These findings reveal that a company with a disintegrated CSR identity can have more resilient capabilities to bring about change, given its openness to learning, desperation for stability and hence more room for structural elaboration. Similarly, a strong corporate heritage identity is not necessarily indicative of a reciprocal link between espoused values and activity. Conversely, an enduring corporate heritage identity may not necessarily be improvisatory for autonomous capabilities to bring about change, but for the willingness of actors to enable co-engaged learning.

Governance issues especially in relation to dealings with small-scale farmers constitute key sources of conflict and power struggles. The social reality of CSR is mainly reinforced by conflicting mandates and interests of sustainability managers and practitioners; the contested terrain of a skewed focus on reputational risk mitigation with less focus on ethical investment and project design flaws such as undue homogenisation of farming cohorts, respectively.

Emerging evidence from the case studies reveals that small-scale farmers, being minorities in the value-chain have been negatively affected by the contested ideological terrain of power struggles—amidst poor climate conditions (see Fig. 8.4). There has also been a steep decline of registered small-scale sugarcane farmers from 50,000 farmers in 2002/03 to 18,860 growers in the 2015/16 farming season; being the season which recorded the most devastating drought in 100 years. While increase in input prices, severe drought resulting in poor land quality, inadequate financing opportunities and access to new market opportunities are partly responsible for the decline in the number of small-scale farmers, threats to economies of scale such as the failure of the one-hectare system, tribal and communal land system, inadequacies of co-operative and contract farming, and poor governance practices are chief among the underlying constraints to sustainable farming.

There are patterns which show that CSR in practice is focused on documenting positive project impacts (with little or no attention to underlying processes of and interventions for social learning), fostering reputational capital and legislative compliance, to secure future project funding. It was also observed that attention is gradually shifting away from fostering project outcomes and life-cycles for sustainable development to the struggle for maintaining project-funding cycles amidst turbulence in the agricultural sector. Following the foregoing observation, monitoring, evaluation and learning interventions which offer context-specific guidelines for uncovering existing and potential behaviour which mitigate against the culture of social learning for sustainable development in local economic development projects would be a welcome addition to structural elaboration.

11 Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that the potential for organisational learning for change is at the crossroad of social responsibility and heritage identity. The uptake of CSR institutionally and in practice illuminates the efficacy of the taken-for-granted mechanisms which foreground the essence of CSR in practice. Insights into how social learning can occur were buttressed by the efficacy of social interaction and reflexive deliberations which can give room for the emergence of new practices.

The interaction and negotiation between structural conditionings and the will of the agent reveal that the positioning and autonomy of agents determine their ability to enable institutional changes. While the relationship between the structural-cultural and personal emergent properties identified in this study is not linear, as cognitive resources which can facilitate the necessary change are inherent in implicit assumptions which advance productive diversity in the terrain of meso-level agency. Future research should explore how the terrain of meso-level agency can be harnessed to exert power for the greater good, given contextualised institutional setbacks and complexities. The onus is on corporate citizens to develop new lenses for approaching and embracing the multi-layered co-engagements which structural conditionings foster or endanger in order to develop new ways of seeing, thinking and relating to structure and power.

The ability of CSR corporate identity to foster social learning at the organisational level is largely influenced by company-specific factors arising from the diversity in corporate history, structure, culture, vision, mission and ethos. Willingness to actively and sensitively channel external and enabling aspirational identities which transcend prescriptive ambitions can foster a change in attitudes towards sustainability amongst corporates. Skewed focus on the acquisition of the license to operate, sustainability of business practices and the quest to conform to national and global best practices can undermine the capacity to harness social reality to leverage social learning.

Governance issues especially in relation to dealings with small-scale farmers constitute key sources of conflict and power struggles. The social reality of CSR is mainly reinforced by conflicting mandates and interests of sustainability managers and practitioners; the contested terrain of a skewed focus on reputational risk mitigation with less focus on ethical investment and project design flaws such as undue homogenisation of farming cohorts, respectively. Management functions at varied hierarchical structures draw on diverse resources and rules in different institutional and social contexts to produce mandate-orientated change learning and outcomes. For example, sustainability managers and communication officers, extension officers and local economic development officers all perceive legitimation differently and have the power to enable/disable associated structural conditioning at will. Practitioners’ transformative agency is largely dependent on the willpower to bring about desired change(s) in practice, which demands persistent interventions for gradual changes via structural elaboration.

As such, CSR is predominantly influenced and redefined by the activities of practitioners, which has implications for understanding inherent agential capabilities and facilitating the culture of social learning. Espoused CSR at the organisational level and practices at the social level are significantly dependent on legitimation, with lower tendencies for autonomy, creativity and reciprocity from actors to structure. Familiarity with and mastery of structural conditionings as well as the prescriptive nature of practices hamper the capacity of agents to learn and enable organisational and social learning for social change. However, vulnerability to power struggles can induce the quest for social learning and equally enable reflexive deliberations and awareness of the urgency and particularity of situated problems. Continuous integration between actors could encourage the reciprocity of practices at both the organisational level and social context.

Notes

- 1.

Note that Archer does not separate these in reality, but only analytically.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Greenwich: CT JAI Press.

Archer, M. S. (1995). Realist social theory: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archer, M. S. (2011). Morphogenesis: Realism’s explanatory framework. In: M. S. Archer (Ed.), Sociological realism. New York: Routledge.

Aucamp, I. C. (2015). Social Impact Assessment as a tool for social development in South Africa: An exploratory study. PhD thesis, University of Pretoria.

Babarinde, O. A. (2009). Bridging the economic divide in the Republic of South Africa: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Thunderbird International Business Review, 51, 355–368.

Balmer, J. M. (2007). Identity studies: Multiple perspectives and implications for corporate-level marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 41, 765–785.

Balmer, J. M. (2013). Corporate heritage, corporate heritage marketing, and total corporate heritage communications: What are they? What of them? Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 18, 290–326.

Balmer, J. M., & Burghausen, M. (2015). Explicating corporate heritage, corporate heritage brands and organisational heritage. Journal of Brand Management, 22, 364–384.

Balmer, J. M., & Burghausen, M. (2018). Marketing, the past and corporate heritage. Marketing Theory. 1470593118790636.

Balmer, J. M., Fukukawa, K., & Gray, E. R. (2007). The nature and management of ethical corporate identity: A commentary on corporate identity, corporate social responsibility and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 7–15.

Balmer, J. M., & Greyser, S. A. (2002). Managing the multiple identities of the corporation. California Management Review, 44, 72–86.

Balmer, J. M., Powell, S. M., & Greyser, S. A. (2011). Explicating ethical corporate marketing. Insights from the BP Deepwater Horizon catastrophe: The ethical brand that exploded and then imploded. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 1–14.

Balmer, J. M., & Soenen, G. B. (1997). Operationalising the concept of corporate identity: Articulating the corporate identity mix and the corporate identity management mix. Strathclyde: Department of Marketing, University of Strathclyde.

Balmer, J. M., & Soenen, G. B. (1999). The acid test of corporate identity management™. Journal of Marketing Management, 15, 69–92.

Balmer, J. M. T. (2009). Corporate marketing: Apocalypse, advent and epiphany. Management Decision, 47, 544–572.

Balmer, J. M. T., Stuart, H., & Greyser, S. A. (2009). Aligning identity and strategy: Corporate branding at British airways in the late 20th century. California Management Review, 51, 6–23.

Bansal, P. (2003). From issues to actions: The importance of individual concerns and organizational values in responding to natural environmental issues. Organization Science, 14, 510–527.

Birkigt, K., & Stadler, M. M. (1986). Corporate identity, grundlagen, funktionen und fallspielen. Landsberg an Lech: Verlag Moderne Industrie.

Blanding, M. 2014. The surprising link between language and corporate responsibility. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hbsworkingknowledge/2014/03/24/the-surprising-link-between-language-and-corporate-social-responsibility/#30bb5d211660. Accessed on July 3 2020.

Blundel, R., Ippolito, K., & Donnarumma, D. (2013). Effective organisational communication: Perspectives, principles and practices. Pearson Education: Harlow.

Bravo, R., Matute, J., & Pina, J. M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a vehicle to reveal the corporate identity: A study focused on the websites of Spanish financial entities. Journal of Business Ethics, 107, 129–146.

Bruhn, S. (2013). Corporate social responsibility: A case study of consumers’ perception of McDonald’s use of CSR in relation to image and reputation. Bachelors Degree, Aarhus University.

Burghausen, M., & Balmer, J. M. (2014). Corporate heritage identity management and the multi-modal implementation of a corporate heritage identity. Journal of Business Research, 67, 2311–2323.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 972–992.

Cornelissen, J. (2014). Corporate communication: A guide to theory and practice. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Dartey-Baah, K., & Amponsah-Tawiah, K. (2011). Exploring the limits of Western corporate social responsibility theories in Africa. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2, 126–137.

De Luque, M. S., Washburn, N. T., Waldman, D. A., & House, R. J. (2008). Unrequited profit: How stakeholder and economic values relate to subordinates’ perceptions of leadership and firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53, 626–654.

Deegan, C. (2002). Introduction: The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures—A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15, 282–311.

Elder-Vass, D. 2010. The causal power of social structures: Emergence, structure and agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elkington, J. 2018. 25 Years ago I coined the phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” here’s why it’s time to rethink it. https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it. Accessed on July 4 2020.

Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10, 102–117.

FAO, IFAD, & ILO. (2010). Agricultural value chain development: Threat or opportunity for women’s employment?. In: S. D. Villard (Ed.), Gender and rural employment policy brief.

Godfrey, P. C., Merrill, C. B., & Hansen, J. M. (2009). The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal, 30, 425–445.

Hildebrand, D., Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2011). Corporate social responsibility: A corporate marketing perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 45, 1353–1364.

Ijabadeniyi, A. (2018). Exploring corporate marketing optimisation strategies for the KwaZulu-Natal manufacturing sector: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Marketing and Retail Management. Durban: Durban University of Technology.

Ionescu-Somers, A., & Steger, U. (2008). Business logic for sustainability. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jäger, S. (2001). Discourse and knowledge: Theoretical and methodological aspects of a critical discourse and dispositive analysis. In: R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis. London: SAGE.

James, P., & Woodhouse, P. (2017). Crisis and differentiation among small-scale sugar cane growers in Nkomazi, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 43, 535–549.

Jones, D. A. (2010). Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 857–878.

Kibert, C., Monroe, M., Peterson, A., Plate, R., & Thiele, L. (2012). Working toward sustainability: Ethical decision making in a technological world. New Jersey: Wiley.

King, M., & Thornhill, C. J. (2003). Niklas Luhmann’s theory of politics and law. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kleyn, N., Abratt, R., Chipp, K., & Goldman, M. (2012). Building a strong corporate ethical identity. California Management Review, 54, 61–76.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. The Journal of Marketing, 54, 1–18.

Mapitsa, C. B., & Khumalo, L. (2018). Diagnosing monitoring and evaluation capacity in Africa. African Evaluation Journal, 6, 1–10.

Marano, V., & Kostova, T. (2016). Unpacking the institutional complexity in adoption of CSR practices in multinational enterprises. Journal of Management Studies, 53, 28–54.

Marcus, A. A., & Anderson, M. H. (2006). A general dynamic capability: Does it propagate business and social competencies in the retail food industry? Journal of Management Studies, 43, 19–46.

Matten, D., Crane, A., & Chapple, W. (2003). Behind the mask: Revealing the true face of corporate citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 45, 109–120.

Mcdonald, L. M. (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in banking: what we know, what we don't know, and what we should know. In: The Routledge companion to financial services marketing. New York: Routledge

Mudrack, P. (2007). Individual personality factors that affect normative beliefs about the rightness of corporate social responsibility. Business & Society, 46, 33–62.

Muller, A., & Kolk, A. (2010). Extrinsic and intrinsic drivers of corporate social performance: Evidence from foreign and domestic firms in Mexico. Journal of Management Studies, 47, 1–26.

Nazari, K., Parvizi, M., & Emami, M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: Approaches and perspectives. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research, 3, 554–563.

Ndhlovu, P. T. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and corporate social investment in South Africa: The South African Case. Journal of African Business, 12, 72–92.

Otubanjo, O. (2012). Theorising the interconnectivity between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate identity. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 3, 74–94.

Porpora, D. (2007). On Elder-Vass: Refining a refinement. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 37, 195–200.

Powell, S. M. (2011). The nexus between ethical corporate marketing, ethical corporate identity and corporate social responsibility: An internal organisational perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 45, 1365–1379.

Powell, S. M., Elving, W. J. L., Dodd, C., & Sloan, J. (2009). Explicating ethical corporate identity in the financial sector. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 14, 440–455.

Reagan, P. M., Tekleab, A. G., Levi, A., & Lichtman, C. (2015). Translating CSR into managerial behavior: Determinants of charitable donation. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015.

Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Aguilera, R. V. (2011). Increasing corporate social responsibility through stakeholder value internalization (and the catalyzing effect of new governance): An application of organizational justice, self-determination, and social influence theories. Managerial Ethics: Managing the Psychology of Morality, pp. 69–88

Rupp, D. E., Wright, P. M., Aryee, S., & Luo, Y. (2011). Special issue on ‘behavioral ethics, organizational justice, and social responsibility across contexts.’ Management and Organization Review, 7, 385–387.

Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., & Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25, 599–633.

SASA. (2017). The South African Sugar Industry. https://www.sasa.org.za/HomePage1.aspx. Accessed on July 4 2020.

Sharma, S. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 681–697.

StatsSA. (2013). A giant step in agriculture statistics. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=1447. Accessed July 2 2020.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610.

Surroca, J., Tribó, J. A., & Waddock, S. (2010). Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources. Strategic Management Journal, 31, 463–490.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., Wade-Benzoni, K. A., Messick, D. M., & Bazerman, M. H. (2000). Understanding the influence of environmental standards on judgments and choices. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 854–866.

Theuvsen, L., Heyder, M., & Niederhut-Bollmann, C. (2010). Does strategic group membership affect firm performance? An analysis of the german brewing industry. Göttingen: GJAE.

Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2014). Evolutionary governance theory: An introduction. Berlin: Springer.

Verbos, A. K., Gerard, J. A., Forshey, P. R., Harding, C. S., & Miller, J. S. (2007). The positive ethical organization: Enacting a living code of ethics and ethical organizational identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 17–33.

Von Loeper, W., Musango, J., Brent, A., & Drimie, S. (2016). Analysing challenges facing smallholder farmers and conservation agriculture in South Africa: A system dynamics approach, 2016(19), 27.

Whittington, R. (2010). Giddens, structuration theory and strategy as practice. In: Cambridge handbook of strategy as practice (pp. 109–126). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgment

The study reported in this chapter was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ijabadeniyi, A., Lotz-Sisitka, H. (2020). CSR, Corporate Heritage Identity and Social Learning. In: Crowther, D., Seifi, S. (eds) Governance and Sustainability. Approaches to Global Sustainability, Markets, and Governance. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6370-6_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6370-6_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-6369-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-6370-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)