Abstract

Tamil Nadu migration survey 2015 was conducted to collect the migration data for Tamil Nadu and understand its impact as the series of Kerala migration surveys helped Government of Kerala in framing policies based on the results. Tamil Nadu migration survey results have estimated that 2.2 million emigrants from Tamil Nadu are living abroad, which is around 3 per cent of the total population of Tamil Nadu. Though Singapore is estimated to receive the largest number of emigrants from Tamil Nadu accounting to 410,000 followed by the UAE with 400,000 emigrants, GCC states between them receive over half of the emigrants, estimated to be 1.1 million. Tamil Nadu has a long history of its people migrating to Singapore and Malaysia and settling there. This had started in the pre-independence era, but the Gulf migration started recently and it gives different opportunities compared to Singapore or Malaysia. This chapter explores the characteristic distinctions of migration to GCC states. Through descriptive data analysis, the chapter explores the demographic data and it shows how 20 per cent of all migrants to non-GCC countries are female whereas it is 9 per cent in case of GCC countries. It also finds that Muslim population migrating to GCC is four times larger than the share of Muslim population migrating to non-GCC countries. Educational status of migrants is naturally different as the GCC countries require different educational qualification as compared to non-GCC countries and it is especially seen that one-third of the migrants to non-GCC countries has a college degree or more. Wage problems seem to exist with return migrants from both the countries, but it is slightly higher in case of GCC countries. As problems such as compulsory expatriation and poor working conditions are some of the reasons for returning among GCC migrants, most migrants in non-GCC countries return due to family problems and/or expiry of contract. Though countries such as Singapore and the USA has higher per-migrant remittance, the analysis and approximation of remittances reveal that GCC countries contribute to almost 50 per cent of all migration. The chapter concludes explaining the need to emphasize the importance of devising policies for migrants to GCC countries by understating their characteristics thoroughly.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

India has the largest migration presence in Gulf regions because majority of Indian migrants end up for employment in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. The initial flow of contractual labour from India started with a small number of 0.16 million in 1985 and it has reached 0.64 million in 2010 (Zachariah and Rajan 2016a). The trends in data on emigration clearances published by the Ministry of Overseas Indian AffairsFootnote 1 (MOIA) of the Government of India primarily reveal migration to six GCC countries, namely Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The above-mentioned countries are referred to as GCC countries throughout this chapter and all the other countries are referred to as non-GCC countries. Since it is mandatory to obtain emigration clearance for Emigration Clearance Required (ECR) passport holders from Government of India to obtain visa from the GCC countries, the records of emigrants are available from MOIA, Government of India. These data enable the researchers to study the trends and other relevant characteristics of all the emigrants from different states of India. The analysis of the data reveals that the workers granted emigration clearances from Tamil Nadu (TN) in 1993 accounted to 70,313 persons, as compared to the neighbouring state of Kerala from which as many as 155,208 persons had emigrated from the state during the same period. Kerala has been the first-ranking state of India sending migrants to GCC countries. In 2006, Tamil Nadu registered a massive increase over Kerala which accounted for 155,631 persons who were cleared for emigration for work as compared to 120,083 in Kerala and retained its position in 2007 too.

Figure 11.1 indicates the volume of Kerala and Tamil Nadu workers who were granted emigration clearance from MOIA over the years. As per the figure, Kerala had the highest flow of migration until 2013. In 2014, Tamil Nadu took over that position. In 2006, Tamil Nadu achieved its peak whereas Kerala registered the same in 2008 with 180,703 workers. After that, there was a decline in the volume of workers from Tamil Nadu as well as from Kerala. However, in 2014, Tamil Nadu surpassed Kerala among the South Indian states and stood behind Uttar Pradesh and Bihar at all-India level, as far as the emigration of workers was concerned. This data is just an indication about trends of emigration to GCC countries which required Emigration Clearance of the passport holders who had completed 12 years of schooling.

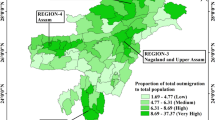

Being one of the top four migrant states based on ECR data, Tamil Nadu did not have comprehensive data about the migration patterns from state. Tamil Nadu migration survey was an answer to the gap. Tamil Nadu migration survey results have estimated that 2.2 million emigrants from Tamil Nadu are living abroad, which is around 3 per cent of the total population of Tamil Nadu. Though Singapore is estimated to receive the largest number of emigrants from Tamil Nadu accounting to 410,000 followed by the UAE with 400,000 emigrants, GCC states between them receive over half of the emigrants, estimated to be 1.1 million. Historically, Tamil Nadu has people migrating to Singapore and Malaysia and settling there. This started in the pre-independence era, but the Gulf migration started recently, and it gives different opportunities compared to Singapore or Malaysia. As its distinctions are clear between the migrations to these different destinations, this chapter explores the characteristics of migration to GCC states.

Objective

This chapter is to understand the specific characteristics of migrants to GCC countries as the policies that are required for half of the international migrants from Tamil Nadu are different from the migrants to non-GCC countries—in terms of their socio-demographic characteristics such as occupation, education, marital status and in their contribution to the economy such as remittances, skill sets. It also understands the data of non-GCC countries in general to know if there is any need for further exploration. The chapter also discusses the future prospects of Tamil Nadu migrants to GCC countries based on the estimates from analysis.

Literature Review

Migration, in India, has been happening since British era but the international migration scene is not studied in depth until recently. In fact, one of the largest surveys for migration was conducted by the Centre for Development Studies, Kerala, in 1998 to explore the international migration in Kerala. Studies that explore the characteristics of Indian migrants to the UAE shows that around 40 per cent are production-related workers—ones that work as electricians, electronics equipment operators, plumbers, welders, sheet metal workers and construction workers (Zachariah, Kannan and Rajan 2002a; Zachariah, Prakash and Rajan 2002b; 2004; Zachariah, Mathew and Rajan 2003). The educational status of these workers is less than secondary except for 3 per cent of them. The average work hours per day of migrants range from 8 to 13 hours. This study also found that almost 22 per cent of migrants have delay in getting their wages. These details compel to understand the uniqueness in the migration to the UAE and other GCC countries. It also makes the comparison with the non-GCC countries necessary if the conditions are different in general. A panel of data analysis of Kerala migration study series shows that the remittances to Kerala has been growing and it estimates that it stands at Rs 71,442 crores. This is 36.3 per cent of Kerala’s State Domestic Product (SDP) equivalent and proved to be significant source of development to the state (Zachariah and Rajan 2016a). Tamil Nadu as a state is larger in area when compared to Kerala and it is one with more population, more SDP than the neighbour, but the international migration seems to be similar in the states as per the ECR data (MOIA 2013). As 90 per cent of the Kerala migrants are going to GCC countries and this proportion is 50 per cent in case of Tamil Nadu, it is required to understand the remittances from Tamil Nadu migrants in GCC countries to analyse the economic impact and development support that the state is able to receive (For Punjab, See Rajan and Nanda 2015; Varghese and Rajan 2015).

Data and Methods

This chapter uses the data obtained in Tamil Nadu migration survey 2015 (Rajan et al. 2017) based on study conducted by Centre for Development Studies. Other secondary data sets are also referred from data published by Ministry of overseas affairs yearly based on the ECR passports cleared for emigration.

Descriptive statistics are the major methods used for analysis. Some of the tables obtained from Rajan et al. 2017 have been synthesized for the use of the study.

Throughout the presentation of results, the countries, namely Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, are referred to as GCC (Gulf cooperation council) countries and others as non-GCC countries simply for the objective of our analysis. It is also to be noted that though this chapter talks about international migration, some of the abbreviations used in the presentation of results are: EMI—Emigrants and REM—Return Emigrant are the categories of international migrants and OMI—Out-migrants and ROM—Return out-migrants are the categories of migrants that migrate within the country across different states in India.

Results

Demographic and social profiles of migrants to GCC countries and non-GCC countries— A Comparison.

Religious Distribution of Tamil Nadu Migrants to GCC and Non-GCC Countries

According to the 2011 Census, Tamil Nadu’s population consists of 87.58 per cent Hindus, 6.12 per cent Christians and 5.86 per cent Muslims. The religious composition (Table 11.1) of the emigrant population is different from religious composition seen in the total population of Tamil Nadu. The majority of the emigrants are Hindus and accounted for 78.5 per cent, 8 per cent of them are Christians and the remaining 13.3 per cent are Muslims. Muslim emigrants are represented more in GCC countries as compared to the Tamil Nadu average—25.4 per cent of Saudi Arabia emigrants from Tamil Nadu are Muslims and this share of Muslim emigrants is over 20 per cent for all the GCC countries except for Oman, which has 14.3 per cent of Muslims in total emigrants which is still above the Muslim emigrants share of overall emigrants from Tamil Nadu. Hindu share of emigrants in GCC countries ranges from 64 per cent to 70 per cent which is well below the overall share of emigrants. In case of non-GCC countries, the Hindu share (88.9 per cent) of emigrant population is way over the overall share and the Muslim (3.8 per cent) share is well below it. In the case of Christians, their share in emigrant population from GCC and non-GCC countries is similar and closer to overall share of 8 per cent of Tamil Nadu emigrants except for Oman and Qatar where Christians share 16.3 per cent and 11.8 per cent of the emigrant populations respectively.

One of the reasons for the larger share of Muslim emigrants in Gulf countries may be due to chain migration. When the infrastructure projects had started picking up in Gulf countries in the early 1970s, labourers from India and other South Asian countries were attracted to GCC countries. However, since the majority of population in these countries was Muslims, Hindu immigrants did not feel comfortable with them due to cultural contrast. With a great difference in food and living habits among these two, Hindus found it difficult to live with Muslims, hence Singapore and Malaysia became the favourable destinations for Tamil migrants due to its stronger diaspora presence.

Distribution of Tamil Nadu Migrants and Return Migrants by Sex

The analysis of emigrants by sex (Table 11.2) shows that the share of women among Tamil emigrants to GCC countries was less. It may be due to numerous restrictions on women employment including their infamous kafalaFootnote 2 system for migration monitoring. Of all the emigrants in GCC countries, only around 9 per cent were women on an average, and this percentage is even lesser (5.6 per cent) if we include Saudi Arabia also which has stricter laws on women rights (Rajan and Joseph 2013, 2015).

This comparison of distribution of sex among return migrants with emigrants is just to see if there is any basic difference in the travelling pattern. From the results (Table 11.3) we see that there is a significant difference in the distribution between emigrants and returned emigrants in case of non-GCC countries. It is observed that the male-female ratio is 80:20 in case of emigrants whereas the ratio is 93:07 in case of return migrants. This might be because that emigrant group contains female population who migrate due to marriage and the returned emigrants are mostly the male population who come back alone to get settled. In fact, this difference is expected as a basic aspect of the classification, emigrants and return emigrants.

Results from Table 11.4 show that among migrants to GCC countries, 50 per cent belong to the age group of 20–34 years against the non-GCC countries where the presence of this age group is 54 per cent. Exceptions to this is Bahrain—where 31 per cent of the migrants were aged from 20 to 34 years and 51.7 per cent in the age group 30 to 49 years. The percentages of TN migrants in these two age groups in Kuwait were 42.3 and 40.0 respectively. Usually the migrants travelling to the Gulf countries have to return to their home country after mandatory retirement at the age of 60 or 62 (or in special cases of 65) years or after taking voluntary retirement around 50 years of age since Gulf countries do not take them as their citizens. Therefore, all the migrants after retirement are supposed to return to their home country. This is confirmed from the data that only very few (negligible percentage) migrants stay in GCC countries beyond 65 years of age. Kuwait and especially Bahrain show different pattern of distribution of migrants than that of the rest of the four GCC countries. The percentages of migrants in the age group 50 to 64 years are nearly twofold than those found in these age groups are in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman and Qatar. Bahrain has people, mostly migrants, to work as labourers in non-agricultural sector and for domestic help (see Table 11.6). As this work needs good experience, the migrants who start late in the migration process migrate to countries such as Bahrain and Kuwait.

Educational Status of TN Migrants and Impact of Migration on Their Occupation

Educational status of the migrants in Gulf (Table 11.5) for class 10 to class 12 group which constitutes around 26.3 of TN migrants and the share of migrants completed class 10 to class 12 is around 34.5 per cent in the UAE, a country where employer sponsorship for workers required at least 10th class. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have migrant share of 33.9 per cent and 33.1 per cent respectively.

Table 11.5 presents the percentages of Tamil Nadu migrants to six GCC countries and non-GCC countries by their educational level. As the data in the table suggests, the percentages of illiterate migrants ranged between the least (3.4) for Bahrain and the most (9.2) for Oman. Some interesting patterns may be observed from the data. Among the migrants having completed schooling from class 1 to class 9, the maximum percentage (25.1) was employed in Saudi Arabia, followed by Kuwait (21.5) and Bahrain (20.7). In the UAE, Qatar and Oman, the percentage staggered at around 17.5. Interestingly, as one moves from “Illiterate” category to class 10 to class 12, it is observed that barring Qatar and Bahrain, the percentages of migrants with educational qualification (years of schooling) showed increase in rest of the four GCC countries. By and large, the highest percentage of migrants in GCC countries is in the class 10 to class 12 categories of schooling.

The last two categories of education in Table 11.5 give the percentages of Tamil Nadu migrants to Gulf countries with some technical qualifications and those having academic degrees like post-graduation and PhD who may be absorbed in Gulf countries as university/college teachers. The migrants having acquired some technical skills and received certificate/diploma after successfully completed training at the government Industrial Training Institutes (ITI), have had better career prospects in countries like Bahrain (37.9 per cent), Qatar (32.9 per cent), Kuwait (26.9 per cent), the UAE (25.6 per cent) and Oman (22.4 per cent). As the data suggests, Bahrain and Qatar had absorbed relatively more migrants in jobs requiring technical skills in various traits to meet the demand of semi-skilled and skilled workers in industries. The demand for post-graduates and PhD degree holders seems to be relatively more in Oman where maximum percentage of Tamil Nadu migrants (21.4) are located, followed by the UAE (17.6), Qatar (17.1) and Saudi Arabia (11.8). The demand of academic degrees holders seems to be least in Kuwait (11.5) and Bahrain (10.3). Oman has relatively better facilities for higher education and health as compared to other GCC countries.

In the overall migrant’s population from TN, people who are illiterate represent 7.8 per cent and illiterates are more than average in non-GCC countries and less than average in most of the Gulf destinations except Oman. More illiterate population is seen in non-GCC countries which may perhaps be partially attributed to the migration of children within 6 years of age as these countries are favourable destinations for family migration as against GCC countries.

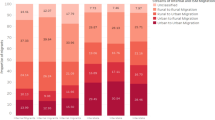

Type of Employment of Tamil Nadu Migrants to GCC and non-GCC Countries Before and After Migration

Table 11.6 presents the percentages of Tamil Nadu migrants by type of employment before and after migration. The table gives the scenarios of the unemployment-driven migration and also migration which took place due to wage differentials between countries of origin and destination. In every case, share of employees in private sector had increased after migration. This is expected as most of the migrants go abroad to get a better salary and improved lifestyle. Also, private enterprises provide higher salaries to recruit skilled/qualified migrants. Labourers in non-agricultural sector had also shown increase, though by a small margin except in two GCC countries, namely, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, where demand for construction labourers was usually high. Next to that is agricultural sector where the labour employment had recorded a decrease at an average of 5 per cent per annum. This steep fall could be attributed to drought conditions, unemployment, and low income for agricultural labourers in the state that they prefer to migrate and work in different occupations. Most of them work as non-agricultural labourers usually after migration. Household workers’ employment shared constant in most cases before and after migration except for non-GCC countries where it was raised by 2.1 per cent. This could be justified as countries included USA, UK and Australia which also record high demand for domestic workers. Percentages of all those migrants who were self-employed before migration decreased after migration. This is true in case of all the GCC and non-GCC countries. Will it be correct to interpret that this decrease in the percentages of self-employed migrants after migration may be attributed to high occupational mobility in both the GCC and non-GCC countries due to availability of better employment prospects after moving to GCC and non-GCC countries? However, the data supports the phenomenon of the decrease of self-employed migration after migrating to both GCC and non-GCC countries

Return Migrants of Gulf Countries and Their Satisfaction About Their Wages

This section explores the problems of wage discrepancy faced by return migrants from Gulf. This can also be seen in terms of expectations versus reality. “Lucrative Salary” is one of the main reasons Tamil Nadu migrants travel to Gulf countries (see also Zachariah, Nair and Rajan 2001, 2006). Their expectations rise through what they read and what they heard or got information through communication. Among all returned migrants from GCC countries, 24.1 per cent of Tamil Nadu returned migrants faced wage problems, comparatively higher to 20.4 per cent facing problems among all Tamil Nadu returned migrants observed in Tamil Nadu migration survey 2015. In Table 11.7, it could be seen that this number is way higher in case of migrants in Kuwait (30.1 per cent) and migrants to Saudi Arabia and Bahrain also have migrants having more wage problems than other Gulf migrants Rajan, Prakash and Suresh 2015). These countries have been known for hiring construction and domestic labour from India, proportionately higher compared to other GCC countries such as the UAE.

Table 11.8 shows the percentages of the return migrants from GCC and non-GCC countries answering on the specific question: “Have you received the salary that was promised?” It is heartening to note that a large percentage of the return migrants from the GCC and non-GCC countries expressed satisfaction that the salary received by them was same as what was promised before their emigration from Tamil Nadu. It may be observed from the table that highest percentage (91.1) of return migrants from Oman had reported that they received the salary they were promised before coming; followed by those who returned from Bahrain (89.5). In case of return migrants from rest of the GCC and non-GCC countries, the percentages of those receiving the amount of the salary they were promised ranged between 74.2 for Qatar and 76.3 for the UAE. Nearly the same situation was for non-GCC countries. The maximum percentage of return migrants who did not answer the question was 4.8 for Kuwait. In the rest of the four GCC countries, namely, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman and Bahrain, the non-response to the question ranged from the minimum of “0” per cent for Qatar and Kuwait, to a maximum of 2.0 per cent for the UAE.

Among those return migrants from GCC countries who said “No” to the question, the maximum percentage was for Qatar (25.8) followed by those who returned from Saudi Arabia (24.5). In these two GCC countries (Qatar and Saudi Arabia), relatively a large percentage of return migrants complained that they were not paid what they were promised by their employer before coming to these countries. Surprisingly 21.7 per cent of Gulf return migrants in the UAE said that they did not receive the pay as they were promised despite the fact that the UAE has been the most preferred destination among the Gulf countries because of their employment security.

Percentages of Return Migrants from Gulf Countries Who Reported Their Grievances to the Indian Embassy

Table 11.9 gives the percentages of Tamil Nadu return migrants from six Gulf countries who reported host of problems they faced in Gulf states to their country ambassador in their respective countries. As can be seen from the table that a large percentage of the return migrants to six GCC countries did not report any problem they faced during their stay in the country. However, the maximum percentage (96.8) of return migrants who did not report any problem was from Qatar followed by the UAE (94.0). The returned migrants who stayed in Bahrain seem to have reported relatively more problems to the embassy/ambassador. Not many had reported any grievances against their employers.

Five types of problems/grievances were “Grievances against employer”, “Problems related to salary”, “Problems of communication due to language”, “Harassment from local police”, and “Other types of adjustment problems”.

With regard to the five problems stated above, only 0.4 per cent of return migrants from the UAE and 2.2 per cent of return migrants from Oman had reported grievances against their employers. Among the return migrants staying in the rest of the four GCC states, namely Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain, none had spoken against their employer to the Indian embassy officials. However, all the migrants returning from the six GCC countries had some or the other problem pertaining to their pay. The majority (9.2 per cent) of Tamil Nadu return migrants from Saudi Arabia complained more problems of payment of their salary and other pay-related issues, followed by return migrants from Bahrain (5.3 per cent), Kuwait (4.8 per cent), the UAE (4.4 per cent) and Oman (4.4 per cent). Interestingly, barring Saudi Arabia, in the rest of the five GCC countries the problems concerning the pay of return migrants were much less than the ones that returned from the non-GCC countries.

As expected, return migrants staying in GCC countries may have had the problems of communication due to difference in spoken languages. Nevertheless, only a small percentage of the return migrants staying in three GCC countries found communication problem. Their percentages in decreasing order of magnitude were Bahrain (5.3), Kuwait (2.4) and the UAE (0.4). Harassment by local police was experienced by a negligible percentage of migrants. Thus, the TN return migrants from GCC countries had nothing serious to report to the personnel of Indian embassy in connection with their stay in these countries (See Table 11.9).

Reasons for Returning of Tamil Nadu Migrants from Gulf Countries

In this section we focus upon the reasons for return of Tamil Nadu migrants from six GCC countries to their native country. In Table 11.10 below, the information on eight reasons for the return of TN migrants to home country has been tabulated by place of residence in the Gulf countries. As the data in the table suggests, a large percentage of TN migrants in six GCC countries reported the reason for their return to their home country as the expiry of their contract. Normally for a migrant who had attained the age of superannuation, the contract may not be renewed. If the contract is not renewed, under any circumstances, the migrant is required to leave the country as the employer is not obliged to arrange the resident permit to such migrants. However, some of the migrants may manage to travel again with contract renewed or with a contract signed with a new employer. As expected, the percentages of return migrants vary from country to country. The highest percentage of TN migrants who returned to their native place was 51.1 for Oman followed by Qatar (45.2) and Bahrain (42.1). In the rest of the three GCC countries, the percentages staggered between a minimum of 30.9 per cent for the UAE and maximum of 37.3 for Kuwait.

By and large, the percentage of TN migrants reporting the reason as “Family Problem” for their return stood as the second after the reason “Expiry of Contract”. The percentages of TN migrants, who gave the “Family Problem” as the reason for their return, were 25.3 for Kuwait, followed by Saudi Arabia (22.0), Oman (20.0) and the UAE (18.9). The least percentage (5.3) of migrants who took decision for their return because of “Family Problem” was for Bahrain. All those migrants who return due to family problems are the ones who would have left their family behind and it is viewed as bigger social cost if these families are unattended.

Another prominent reason for migrants’ return was their “Poor Health”. Among the TN migrants who stated this reason for their return, a relatively large percentage of migrants returning from Qatar was 16.1 followed by 11.6 for the UAE. The percentages of migrants (in decreasing order of magnitude) returning from the rest of the four GCC countries for “poor health” were 8.8 per cent for Saudi Arabia, 8.4 per cent for Kuwait, 6.7 per cent for Oman and 5.3 per cent for Bahrain.

The migrants who reported the reason for their return as “Low Wages”, the maximum percentage was for the UAE (12.4), followed by Qatar (9.7), Saudi Arabia (8.8) and Kuwait (7.2). In Bahrain, “low wages” does not seem to be the push factor for migrants to leave the country. The next reason “Voluntary Retirement” has not been a significant cause for return migration. Although “Compulsory Expatriation” has not been a major reason in the GCC countries, in Bahrain (10.5 per cent) and Kuwait (6.0 per cent), it was higher than in the rest of the four countries.

Now, Tami Nadu is a state of 72 million people and there is wide demand for skilled labour like construction labour, carpenter, electrician, plumber, lathe worker in industries and so on. There is a recent trend in in-migration of this labour supply from other states like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. But Table 11.11 shows that around 55 per cent of the returned Gulf migrants have manual skills. These skills are either underutilized or underpaid for if they seek work and eventually fade off when not being employed for a time period of more than 6 months to a year. Other managerial skills and professional skills of return migrants also should be enriched through training and skill-management practices. This is clearly an untapped potential that the state can use.

Remittances by TN Migrants of the Gulf Countries and Their Utilization by Left Behind Families at the Origin

Tamil Nadu received Rs 61,843 crores of remittances as calculated by ECR method (Zachariah and Rajan 2016a). This section calculates country-wise remittances only based on household remittances data from Rajan et al. 2017 and emphasize the Gulf countries’ share in household remittances. Tamil Nadu received Rs 14,551 crores as remittances from migrants based on household remittances reported from Tamil Nadu migration survey 2015. Remittances are calculated country wise by taking proportional remittances country wise from the household-wise remittances reported and then the total remittance is distributed. Tamil Nadu received highest proportion of remittances from a non-GCC country—Singapore—a country where the presence of Tamil Nadu migrants and Tamil diaspora is very strong. Among the migrants from GCC countries, Saudi Arabia is the destination country from which 17.39 per cent, that is Rs 2530.66 crore, is received. Migrants to the UAE contribute to 15.56 per cent of household remittances to Tamil Nadu (Table 11.12).

In all, migrants to GCC countries send Rs 7019.51 crore to Tamil Nadu and contribute to 48.24 per cent of the state’s total remittances (Table 11.13). Appendix has the complete list of countries and the remittance received.

Most of the migrants’ families use the remittances received in building a house, which is considered every Indian family’s dream, and Tamil Nadu has the same sentiment. Intriguingly, people spend their remittances also on education and health care of their family. Though education and health care should typically be provided by the state, it is not preferred by people due to quality issues. It becomes a part of everyone’s lifestyle to give children better education and pursue quality treatment, and in fact people migrate to build their savings in order to send their children to a better college in future. This is an area that seeks attention (Table 11.14).

Future Prospects of Gulf Migration from Tamil Nadu and Recommendations

Gulf migration, as discussed, was always seen as a high-paying prospect for the economically downtrodden and the ones who desired to improve their status quo. They have always been aware of the risks that lay ahead of them when working under kafala system, where they had to pledge their passport to work for a contract period. Of course, they prospered when they worked there. But there was no stability in their occupation or income when they completed their contract and come back.

Table 11.6 shows the occupation conversion percentage of migrants to GCC countries. Percentage of labourers in non-agricultural sector has gone up and the percentage of labourers in agricultural sector has come down. The conversion of labour from agricultural sector to non-agricultural sector is clearly seen and when these employees return from abroad, the government should incentivize the labour to move in the direction where the domestic demand for labour is more.

In answer to a question about skills acquired (Table 11.11) by the migrants abroad, 61.9 per cent returned from Saudi Arabia and 60.2 per cent returned from Kuwait have manual skills. About 55.2 per cent of migrants from GCC develop manual skills and have experience in it for a long period. There has been a clear demand for manual labour (in sectors like construction, carpentry and plumbing) in the state and the state imports a lot of labour from neighbouring states for these works. But they are less prone to join these sectors without better wages as they would compare the wage differential between here and abroad. Minimum wage legislation in these sectors would encourage the returned migrants to participate in these sectors and retain the existing labour force.

Price of crude oil took a fall over a period of time and is at its low of late. This has been a result of thought on global warming and growing awareness of nations about solar energy and other alternate sources of energy. This has led the GCC countries, which highly depend on oil trading for their GDP, to shutdown many ongoing infrastructure projects and stop creation of new projects for their development. This has led to reduction in demand for migrant labours in these countries. Recent incidents in Oman (Omanisation) and Saudi Arabia (mass job reduction) have fuelled this growing concern. There have also been job losses across all Gulf countries and this signifies the return of huge labour force to the state. As discussed earlier in one of the chapters (Zachariah and Rajan 2016b), rehabilitation programmes for returned labour is as necessary as the pre-migration workshops that are conducted. These programmes serve the same purpose—to adapt to the local culture and understand the needs of the job market and where they stand with their present skill set. This would help the state to achieve its share of demographic dividend and avoid social costs incurred due to unemployment.

Notes

- 1.

MOIA was established in 2004 as Ministry of Non-Resident Affairs in May 2004 and renamed in September 2004 to handle services for non-resident Indians and persons of Indian origin. It is presently merged with Ministry of External affairs and carries out all the functions.

- 2.

Kafala system is a system used to be in practice to monitor coming in migrant labours through in-country sponsor (usually employer) for every worker. This was widely practised in Gulf countries.

References

MOIA. (2013). Annual Reports. New Delhi: Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, Government of India.

Rajan, S. I., & Joseph, J. (2013). Adapting, Adjusting and Accommodating: Social Costs of Migration to Saudi Arabia. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2013: Social Costs of Migration (pp. 139–153). New Delhi: Routledge.

Rajan, S. I., & Joseph, J. (2015). Migrant Women at the Discourse–Policy Nexus: Indian Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia. Chapter 2. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2015: Gender and Migration (pp. 9–25). New Delhi: Routledge.

Rajan, S. I., & Nanda, A. K. (2015). Transnational World and Indian Punjab: Contemporary Issues. In S. I. Rajan, V. J. Varghese, & A. K. Nanda (Eds.), Migrations, Mobility and Multiple Affiliations: Punjabis in a Transnational World (pp. 1–36). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Rajan, S. I., Prakash, B. A., & Suresh, A. (2015). Wage Differentials Between Indian Migrant Workers in the Gulf and Non-migrant Workers in India. Chapter 20. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2015: Gender and Migration (pp. 297–310). New Delhi: Routledge.

Rajan, S. I., Sami, B. D., & Raj, S. A. (2017). Tamil Nadu Migration Survey 2015. Economic and Political Weekly, 52(21), 85–94.

Varghese, V. J., & Rajan, S. I. (2015). Migration as a Transnational Enterprise: Migrations from Eastern Punjab and the Question of Social Licitness. Chapter 7. In S. I. Rajan, V. J. Varghese, & A. K. Nanda (Eds.), Migrations, Mobility and Multiple Affiliations: Punjabis in a Transnational World (pp. 166–195). New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2007). Migration, Remittances and Employment: Short-term Trends and Long-term Implications. Working Paper 395. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2008). Costs of Basic Services in Kerala: Education, Health, Childbirth and Finance (Loans). Working Paper 406. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2009). Migration and Development: The Kerala Experience. New Delhi: Daanish Publishers.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2010a). Migration Monitoring Study 2008: Emigration and Remittances in the Context of Surge in Oil Prices. Working Paper 424. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2010b). Impact of the Global Recession on Migration and Remittances in Kerala: New Evidences from the Return Migration Survey (RMS), 2009. Working Paper 432. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2012a). Diasporas in Kerala’s Development. New Delhi: Daanish Publishers.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2012b). A Decade of Kerala’s Gulf Connection. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2015a). From Kerala to Kerala via the Gulf: Emigration Experiences of Return Emigrants. Chapter 18. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2015: Gender and Migration (pp. 269–280). New Delhi: Routledge.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2015b). Researching International Migration. New Delhi: Routledge.

Zachariah, K. C., Gopinathan Nair, P. R., & Rajan, S. I. (2001). Return Emigrants in Kerala: Rehabilitation Problems and Development Potential. Working Paper No. 319. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah, K. C., Kannan, K. P., & Rajan, S. I. (Eds.). (2002a). Kerala’s Gulf Connection: CDS Studies on International Labour Migration from Kerala State in India. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

Zachariah, K. C., Prakash, B. A., & Rajan, S. I. (2002b). Gulf Migration Study: Employment Wages and Working Conditions of Kerala Emigrants in United Arab Emirates. Working Paper No. 326. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram. www.cds.edu. Accessed 10 Nov 2018.

Zachariah, K. C., Mathew, E. T., & Rajan, S. I. (2003). Dynamics of Migration in Kerala: Determinants, Differentials and Consequences. Bengaluru: Orient Longman Private Limited.

Zachariah, K. C., Prakash, B. A., & Rajan, S. I. (2004). Indian Workers in UAE: Employment, Wages and Working Conditions. Economic and Political Weekly, XXXIX(22), 2227–2234.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2016a). Kerala Migration Study 2014. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(6), 66–71.

Zachariah, K. C., & Rajan, S. I. (2016b). Emigration and Remittances: Results from the Sixth Kerala Migration Survey. Chapter 16. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), India Migration Report 2016: Gulf Migration (pp. 238–254). New Delhi: Routledge.

Zachariah, K. C., Gopinathan Nair, P. R., & Rajan, S. I. (2006). Return Emigrants in Kerala: Welfare, Rehabilitation and Development. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers and Distributors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rajan, S.I., Rajan, E.S. (2019). Tamil Nadu Migrants in the Gulf. In: Rajan, S.I., Saxena, P. (eds) India’s Low-Skilled Migration to the Middle East. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9224-5_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9224-5_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-9223-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-9224-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)