Abstract

To tackle the serious problems caused by plastic wastes, it is critical to develop new plastic recycling beliefs and behavior, together with recycling skills (4 important steps of recycling: cleanliness, separation, compression, and sorting) of the plastic wastes in environmental education (EE). The study revealed the effectiveness of a plastic waste recycling program adopting an action competence approach with educational interventions using a new plastic waste recycling bin (PRB). The PRB allows further classification of plastic waste types. Seven primary schools in Hong Kong participated in the program. A total of 313 questionnaires which assessed pupils’ classification knowledge, behaviours of plastic waste recycling, and their pro-environmental attitudes in terms of New Environmental Paradigm were received. Semi-structured interview with 27 pupils from the schools were also conducted. Recycling performance (actual behaviour) of using the brown bins (general plastic recycling bin) and the PRBs in the schools was assessed as the evidence of action competence in plastic waste recycling. Comparing the schools which adopted programmes with a combination of two types of recycling bins (brown bin vs. PRB) and interventions (Poster vs. half/full training courses to teach the recycling knowledge and skill), both quantitative and qualitative results showed that learners of the program enhanced their recycling knowledge (K), attitudes (A), and behaviour (B) concerning plastic waste recycling. The recycling performance proved that there is a statistically significant change in the recycling steps, separation and compression. The study provides insights for environmental educators to develop strategic solutions to ease environmental issues as well as putting these actions into practice in schools.

Authors Chi Chiu Cheang and Tsz Yan Cheung are equally contributed for this chapter.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Plastic waste problem become more and more severe in the metropolitan cities owing to the rapid growth in both population and tourism. In 2011, the local government of Hong Kong attempted to tackle the problem by launching campaign to enhance the participation of plastic waste recycling in schools. Yet, the recycling bin used only contained a single compartment that could not avoid contaminations with other wastes and the plastic wastes collected. To promote proper plastic waste recycling practices, an innovative plastic waste recycling bin (PRB) has been launched. The PRB includes eight compartments that collect plastic wastes according to the plastic types. Together with educational interventions, the quality of recycling plastic wastes could be improved. The present study aims at assessing how effective different educational interventions associating with the PRB is to promote the pupils’ action competence for plastic recycling and measure the quality of the recycling plastic wastes by using the PRB in the primary schools.

1.1 The Plastic Waste Problem in Hong Kong

The speedy growth of economic and urban development has led to a drastic increase in the consumption of plastic products, resulting in a tremendous amount of plastic waste all around the world. Plastics are commonly used in our daily life, such as dining ware, toys, and food packaging. Worse still, around 50% of the plastic products are used once and then discarded as waste (Hopewell, Dvorak, & Kosior, 2009).

Metropolitan Asian cities, such as Metro Tokyo, Taipei, Seoul, and Hong Kong, are experiencing rapid growth in both population and tourism. Population pressure and consumption patterns create stress on the local municipal solid waste (MSW) management systems (Table 10.1). Recent statistics indicate that 10,345 tons of MSW are generated every day in Hong Kong (Environmental Protection Department, 2016), of which plastic waste contributes around 2,131 tons and ranks the third among the different types of MSW. The huge amount of durable and voluminous plastic waste places a great burden on the landfills, the major waste management infrastructure in Hong Kong. It is estimated that these landfills will be saturated within the coming 10 years (Environmental Bureau, 2013).

To avoid further aggravation of the waste management problem, a change in the plastic waste recycling behavior of Hong Kong citizens is urgently required. Up to 2013, 16,000 sets of waste separation bins (yellow for metals, blue for paper, and brown for plastics) were placed in public locations such as on curbs, in sport centers, schools, hospitals, etc. (HKSAR Gov’t, 2013). Brown recycling bins (BB) are ubiquitous in the community, especially in the residential estates, for plastic waste collection. Despite the abundance of this recycle-supporting tool, the basic recycling steps such as cleaning, separating, compressing, and classifying the plastic parts before recycling are generally ignored by the public. This ignorance of the correct procedures is one of the major causes of the increase in the cost of post-processing, and the decrease in the quality and quantity of recyclables (Hopewell et al., 2009). This has created an additional burden on the local recycling industry, which had already been facing many difficulties such as limitation of land for recycling plants, the high cost of sustaining their operation, and the lack of invention of new supportive technologies (Tam & Tam, 2006). These problems all hinder the effective recycling of plastic waste in the city.

1.2 Introducing a Newly Designed Plastic Bin

Educators believe that education is the critical key to enhancing knowledge and encouraging positive alternate behavior (Hungerford & Volk, 1990; Kopnina, 2014). It is argued that educating the general public with proper pro-environmental behaviors in relation to plastic waste recycling could improve the quality of recyclables. This is especially true for primary school pupils whose conceptual mindsets regarding the world are developing (Evans et al., 2007). It is reported that young people possess a higher level of awareness of the environment than older individuals (Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000). Yet, their pro-environmental awareness and values tend to drop after age 13 (Pol & Castrechini, 2014). Encouragingly, a study from the United Kingdom found that knowledge from child-orientated EE could affect and transfer to adulthood with sustainable and intended pro-environmental changes (Damerell, Howe, & Milner-Gulland, 2013). Thus, it is necessary to educate primary pupils aged 6–12 in the hope of strengthening their pro-environmental beliefs and values for a sustainable future.

In 2011, the local government of Hong Kong launched a campaign called “Reduce Your Waste and Recycle Your Plastics” with a view to enhance plastic waste recycling in schools. Education kits including card games, CD-ROMs, leaflets, teacher guide books, and posters were provided to encourage better performance of plastic recycling (Environmental Protection Department, 2011). The kit also taught about sorting out the plastic wastes, and schools were given a new bottle-shaped recycling bin (BB) for plastic waste collection, the design of which was thought to be more attractive. However, with only a single compartment, the BBs do not allow users to pre-sort or pre-separate different types of plastic wastes. Users tend to put all the plastic wastes, including unclean articles containing residual food, directly into the BBs, potentially contaminating the other recyclables in place, thus reducing their quality and value.

In order to promote proper plastic waste recycling practices, an innovative plastic waste recycling bin (PRB) has been launched (Chow, So, & Cheung, 2016; So, Cheng, Chow, & Zhan, 2016, Chow et. al., 2017). The PRB includes eight compartments that collect eight types of plastic waste (Appendix 1). Bin users have to further separate and discard the plastic waste into the right compartment according to the plastic type. Prior to discarding the plastic waste, users are educated to clean, separate, and compress the recyclables, if applicable. These pre-disposal steps of recyclables can therefore promote the efficiency of plastic recycling.

1.3 Theoretical Framework

In the local primary school curriculum, schools can choose to implement EE either formally or informally within the curriculum (CDC, 1999). There are many benefits of EE programs in a school setting such as improving pupils’ interpersonal skills, and developing their knowledge, environmental sensitivity, and sense of belonging to nature (Mobley, Vagias, & DeWard, 2009), which are responsible for shaping pro-environmental behaviors. Schools not only benefit from the recycling program by raising the pupils’ awareness of sustainability, but EE goals can also be achieved.

However, there are various factors which hinder local EE development in schools due to the teachers’ tight schedules and lack of specific environmental knowledge or support (Lee, 2000). Gottlieb, Vigoda-Gadot, and Haim (2013) mentioned that other “situational” constraints also prevent schools from carrying out EE such as the provision of recycling containers and facilities, the school’s canteen and food packaging, or even the very short intervention period which means that pupils’ internal values may not be supported enough to achieve a change in behavior. Thus, schools are encouraged to cooperate more with NGOs or other external organizations to carry out Green projects (Cheng & So, 2015), which may provide more resources and funding for environmental troubleshooting. In the present study, the seven local primary schools cooperated with the “I Act, U Act! Plastic Recycling” (IAUA) program to help tackle the plastic waste problem. This may have a greater impact and provide more innovative ideas for pupils to learn about environmental issues.

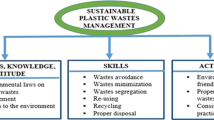

Transforming the theory of environmental sustainability into recycling behavior is not easy without the aid of systematic information and educational tools. The present study employed the “Action competence” approach (Cincera & Krajhanzl, 2013; Jensen & Schnack, 1997; Mogensen, 1997) in the program design by considering the determining factors, such as the promotion of behavior-related knowledge, skills, and awareness, and the perceived behavior of sustaining plastic waste recycling in schools.

1.3.1 Action Competence for Pro-environmental Actions

Action competence refers to the capability of a person to seek solutions to environmental problems and execute the solutions with actions. There are various components to develop competence through education such as transferring knowledge and skills, enhancing commitment, and developing a future vision of sustainable life style and actions (Jensen & Schnack, 1997). The person should develop reasoning and judgement of the environmental issues for action (Cincera & Krajhanzl, 2013; Mogensen, 1997). Jensen and Schnack (1997) further claimed that outcomes of EE designed to modify behaviors alone cannot be sustained. Thus, in addition to EE with behavioral modification, having EE designs involving critical thinking is essential to sustain the new behaviors and owe the capabilities to act in the long run (Seatter, 2011). A revised Bloom’s Taxonomy also states that different dimensions of knowledge including factual, conceptual, procedural, and metacognitive knowledge enhance the learning process that contributes to applying the knowledge in novel situations (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Deficiencies in knowledge obviously hinder environmental behavioral changes (De Young, 2000). Also, it has been found that people with higher pro-environmental knowledge would appreciate nature more (Roczen, Kaiser, Bogner, & Wilson, 2013).

1.3.2 School-Based Interventions for Developing Action Competence

A school-based intervention, in the form of an EE program, encourages the participation of whole schools and the development of an atmosphere conducive to positive behavioral change. It is reported that school-based EE programs may result in great enrichment of children’s environmental knowledge and awareness (Rickinson, 2001; Zelezny, 1999) since schools and teachers are major providers of knowledge and information about environmental issues. Goodwin, Greasley, John, and Richardson (2010) also suggested that school-based EE programs allow children to act as green ambassadors to promote the green messages to their parents or siblings. As a result, messages of proper plastic recycling can be spread widely, from pupils to families and the whole community to bring about a positive recycling outcome through peer influence.

To implement an effective school-based EE program, Jensen (2002) suggested taking the approach of action competence into consideration. Action competence involves two major directions; firstly, it is a concept that pupils have to be able and willing to take action to recycle waste consciously, which is different from a random behavior or habit. Secondly, schools should carry out activities that address the solution of the environmental issues (Jensen & Schnack, 1997). The concept stresses that all actions should be carried out based on solving the problem with pupils’ intention to understand the reason for their actions. This allows pupils to nurture the competence to act and to protect the environment from problems (Jensen, 2002).

1.4 Research Questions and Objectives

There are two kinds of environmental action: (i) direct action to contribute to problem solving and (ii) indirect action to influence others to participate and engage in the problem-solving process (Jensen & Schnack, 1997). Indirect actions usually relate to direct actions, and direct actions are the result of indirect actions. For example, direct action refers to practicing reduce, reuse, or recycle in daily life, while indirect action refers to the promotion of the pro-environmental idea to others such as holding a debate or course.

Hence, the present study applied school-based interventions to create capacity for action competence by installing PRBs in schools with training courses to endorse the actions of plastic waste recycling. The program design involved (i) indirect actions: creating an atmosphere for peer influence, (ii) direct action: installation of PRBs with a poster display to gain knowledge of the plastic waste problem and proper behavior, and the action tool to direct pupils to recycle plastic waste properly.

The program was evaluated by measuring pupils’ pre- and post-knowledge (K), attitudes (A), and behaviour (B) regarding plastic waste recycling and the recycling quality after using the PRBs. A quasi-experimental setting was used to compare the effectiveness of the PRBs and BBs with or without interventions to promote the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of plastic waste recycling in primary schools. The schools were divided into different treatment groups and a baseline study was conducted. The research questions are listed as follows,

-

1.

How does the plastic waste recycling program with different treatment groups (BB/PRB and with/without interventions) affect pupils’ K, A, and B of plastic waste recycling?

-

2.

How do the interventions promote the action competence in the schools?

2 Quasi-experimental Study in Seven Primary Schools in Hong Kong

2.1 Background

The research design involved intervention-based studies, evaluated by both quantitative and qualitative methods. A total of 330 pupils from seven primary schools, from grades 3 to 6, in Hong Kong were recruited to join the plastic waste recycling program called “I Act, U Act! Plastic Recycling” (IAUA).

2.2 Plastic Waste Recycling Program: IAUA

A factorial design with two factors, the bin types and the interventions, was adopted in the study (Table 10.2). Interventions involved poster displays (Fig. 10.1) and training courses. The participating schools were divided into four groups to use either PRBs or BBs for plastic waste collection, and received two types of intervention, respectively. There were two stages of intervention, each of which lasted for 3 weeks. The full training course involved all topics from the general waste to the plastic waste problem in Hong Kong, the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, and recycle) and plastic waste classification. During the full training course, pupils were asked to discuss the reasons for recycling and to do inquiry experiments to understand the reasons why it is valuable to classify plastics into different types to facilitate their recycling. Sharing time was allowed in the course to figure out the views, causes, and solutions to the problems of plastic wastes and recycling.

As the control group for the intervention, the “other teaching” training course (control group) was not provided with lessons about plastic waste classification and recycling, but other topics were taught such as creative thinking. Pupils were invited to join the course in each school. Since the course recruitment was open to all pupils for each school, not all the pupils who answered the pre-tests were included in the training course. Yet the spillover effect could be evaluated during interviews to see if the attending pupils shared the course content with non-attending pupils. This is important in promoting the environmental messages (Hiramatsu, Kurisu, Nakamura, Teraki, & Hanaki, 2014) of the training course.

2.3 The Program Flow

2.3.1 Baseline Study of Plastic Waste in the Schools

At the beginning of the program, a baseline study was conducted to assess the amount and recycling quality (cleanliness, separation, compression, and sorting) of the plastic waste from the currently used plastic waste recycling bins (brown bins) in the schools for two weeks. To assess the recycling quality and quantity, which were the actual plastic waste recycling outcomes, plastic wastes were collected each week from the participating schools and analyzed to serve as a proxy to assess direct action. Ten items were randomly selected from the brown bin for analysis.

2.3.2 Strategic Interventions for Education in Plastic Waste Recycling

First, the assigned schools were distributed a set of three educational posters about plastic waste recycling (Fig. 10.1). These poster sets were posted in each classroom and next to the recycling bin. The poster included the information of the four steps for plastic waste recycling and examples of the different types of plastic waste to facilitate the use of the bin. For schools that used brown bins, the figure showed the school’s brown bin rather than the PRB. The poster set was posted at the assigned schools.

Afterwards, each school was given a full or “other teaching” training course about environmental protection. A total of 70 pupils were randomly selected from each school to join the 8-h training course, the content of which is similar to that described in the previous study (Chow, So, & Cheung, 2016).

3 Methods

This research adopted various methods including a questionnaire and interviews to assess the effect of the interventions on pupils’ general and plastic classification knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours (KAB) regarding plastic waste recycling. Around 60–70 pupils, aged 9.5 on average, were randomly selected from each school to complete the questionnaire with their consent. For statistical analysis, paired t tests were conducted to compare the differences within each group before and after each intervention. Two-way ANOVA and paired t tests were conducted to compare the differences across and within intervention schools with different bin types. All the statistical tests were conducted using the computer software SPSS ver. 21 (IBM Corp., 2012).

3.1 Assessment of Pupils’ Changes in Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours

The assessment included a 30-min questionnaire classification knowledge, behaviours of plastic waste recycling, and their pro-environmental attitudes. The pre- and post-tests were taken by the same pupils. A pre-test was conducted before the intervention and there was a post-test after the courses to assess pupils’ KAB changes. Knowledge included two categories. General knowledge referred to knowledge of the contexts of solid waste management in Hong Kong such as the situations of the local landfill sites, waste hierarchy, or waste management choices (for the questions please see Appendix 2). Specific knowledge involves the knowledge needed to classify different plastic wastes.

Attitude refers to the pro-environmental thoughts about the eco-crisis. The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale was developed by Dunlap and Van Liere in the late 1970s for pro-environmental belief evaluation (Dunlap & Van Liere, 1978). The scale was revised for children and further developed into five constructs: limitation for growth, anti-anthropocentrism, the rights of nature, rejection of human exceptionalism, and eco-crisis (Dunlap et al., 2000; Manoli, Johnson, & Dunlap, 2007). The NEP was found to be able to reflect participants’ ecological views, especially on waste recycling (Chung & Poon, 2001). If a person holds a higher NEP score, he/she values more highly natural assets (Lee & Paik, 2011). In other words, a person is more willing to recycle as this can protect the environment. The NEP scale consisted of 5 Likert-scale statements with selections ranging from strongly disagree (=1) to strongly agree (=5). The eco-crisis construct was selected to assess pupils’ attitudes towards nature in the present study. The revised version of the NEP scale (Dunlap et al., 2000; Manoli et al., 2007) was adopted in the present study; this scale specializes in evaluating the pro-environmental beliefs of children aged from 8 to 10. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for attitudes towards plastic waste recycling revealed by the NEP scale is 0.772, which is within the accepted range of internal consistency.

Skills reflected what pupils would perform before recycling plastic wastes. As for the skill of plastic waste recycling, which refers to the 4-step recycling (cleanliness, separation, compression, and sorting) when disposing of plastic waste, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is 0.707.

3.2 Evaluation of Action Competence and Recycling Quality in the Schools

A total of 27 pupils from each primary school were selected randomly for a face-to-face interview to ask what they thought about plastic waste recycling after the program (Appendix 3). Their reflections were recorded in audio tracks with their prior consent. Some of their suggestions and ideas are summarized in the results.

To assess the recycling quality and quantity, which was the actual plastic waste recycling behavior, the same methodology as the baseline study was applied. Ten items were randomly selected from the brown bin and from each compartment of the PRB for analysis. The recycling quality of the collected plastic waste was quantified in terms of four aspects, cleanliness (CLE), separation (SEP), compression (COM), and sorting (SOR). These four aspects correspond to the four steps of plastic waste treatment proposed in the study. The plastic waste was defined as clean if all residue drink or food had been removed and/or no obvious dirt was observed on the recyclables. The waste was separated successfully when the non-plastic or other types of plastic parts were removed from the item. Items were counted as compressed if they were compressible and had been compressed to diminish the waste volume. If the items were correctly put into the right compartment according to their plastic type, they were regarded as correctly sorted. All four aspects of recycling quality were expressed as an accuracy percentage. The results of the recycling quality reflected how pupils applied their recycling concepts in dealing with the plastic waste.

4 Results

In the baseline study, statistically significant differences were not detected among the schools in terms of recycling quality (Kruskal-Wallis Test, CLE: χ2(6) = 7.807, p = 0.253; SEP: Χ2(6) = 8.281, p = 0.218; COM: Χ2(6) = 8.119, p = 0.230; SOR: χ2(6) = 4.627, p = 0.586) or weight (Χ2(6) = 6.560, p = 0.363), indicating that there was no significant difference in the recycling practices among the different schools before the interventions. The quality data of the waste among schools were compared using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test due to the violation of homogeneity assumption for parametric tests. No bias among the schools in handling plastic waste before joining the program was, thus, assumed. The combination of both factors (PRB and intervention) showed positive improvements in some of the post-test scores for all aspects. Further details of the KAB items along with pupils’ reflections are described in the following sections.

4.1 General Knowledge of Waste Management

In general, pupils’ post-scores of general knowledge of waste management increased after participating in this plastic waste recycling program, although there were no significant levels found among the bin types and the interventions shown in Table 10.3 On average, pupils could achieve 2.3 out of 5 marks for general knowledge. Yet, for question 2 shown in Table 10.4, pupils significantly improved the choice of priority in the waste hierarchy after the program with a 20% increase in accuracy (p = 0.044).

4.2 Specific Knowledge of Types of Plastic Waste After Strategic Interventions

Pupils’ specific knowledge of sorting different types of plastic waste was enhanced after joining the program. In Table 10.3, there was a significant increase in the plastic waste knowledge in schools with intervention received (p = 0.001). Considering both factors, schools receiving interventions and using the PRB improved in the specific knowledge in sorting plastics (p = 0.015). Yet, without interventions, no matter which types of bins (PRB or BB) were used, schools’ mean difference of scores between the pre- and post-tests dropped (refer to the bold digits in Table 10.3). Table 10.4 shows that pupils could remember the plastic types of some items well such as plastic wrap, nylon bags, lactic acid bacteria drink bottles, and food storage bags, with a significant increase in the post-test scores. Pupils were capable of distinguishing the types of plastic waste which are commonly seen in our daily life (for other items, please see Appendix 4). However, there was a slight decrease in the accuracy of identifying the correct types for some of the plastic items such as cleaning bottles, water bottles, CDs, shower curtains, and soft drink bottles. Pupils may not have been familiar with these kinds of plastic waste, which are not so common in school settings.

4.3 Attitudes Towards Plastic Waste Recycling

In Table 10.3, pupils’ belief in the eco-crisis was quite positive in general, as shown in the pre-test. However, two statements showed a significant increase in the post-scores as reported in Table 10.4. More pupils agreed that there are more people living on earth in the future (p = 0.00) and that humans are destroying the natural environment (p = 0.02), which may reflect how they felt towards the local waste problems.

4.4 Procedural Knowledge of Plastic Waste Recycling

The mean difference in scores between the pre- and post-tests decreased in schools using brown bins no matter if there was intervention or not (Table 10.3). This shows that the use of the PRB significantly improved the procedural knowledge of pupils’ recycling of plastic waste (p = 0.013). In Table 10.4, some items, such as question 3 (compression: p = 0.02) and question 4 (separation: p = 0.04), showed a significant increase. Yet, pupils still thought that cleanliness and sorting were difficult to follow, as reflected by the significant decrease in the post-test score in question 2 (cleanliness).

4.5 Promoting Action Competence for Plastic Waste Recycling

Peer influence in promoting indirect action was evidenced. From the group interview, the pupils reflected that they had become more environmentally-friendly after the program. They understood more about how plastic waste is related to the eco-crisis, and the seriousness of the environmental problems urges them to do more. Some of them wished to protect the earth and environment more for their future generations such as by influencing others to become greener. Pupils from the “full training course” reflected that they shared information with their peers and even their families.

After joining the program, I am eager to take part in plastic waste recycling by practicing the recycling 4 steps (cleanliness, separation, compression, and sorting) and I have kept doing it (the practice) till the present. [Pupil A from Group2]

I do share the knowledge of plastic waste recycling with my classmates, friends, and family as they don’t know and have never heard (such knowledge) and I want to teach them…[Pupil B from Group2]

The indications printed on the PRB surface showing the examples of the plastic wastes by type for each compartment are colorful and informative. In schools using the brown bin with intervention, pupils reflected that the poster set allowed them to be more familiar with the knowledge of plastic types. Asked to rank the attractiveness of the poster sets on a 5-point scale (5 = the best), they scored the posters from 4 to 5. However, they did not mention that the brown bin could facilitate the enrichment of knowledge of plastic types.

I will look at the poster and then clean my bottle before recycling (into the brown bin). [Pupil D from Group 3]

Pupils from the PRB schools said that they felt curious about the PRB in their schools and approached it. In contrast, the brown bin only has a single compartment that mixed all plastic wastes together so the pupils thought that it was meaningless to clean, separate, compress, and classify the plastic waste in advance. Although some pupils thought that they had to spend more time discarding their waste when using the PRB by following the proper recycling steps, the posters motivated them to use the PRB more often.

I go near the recycling bin (PRB) and observe the notice of the bin. It is interesting to put plastics into different compartments. [Pupil E from Group 2]

I did not further classify the plastic wastes into types when using the brown bin. [Pupil F from Group 3]

4.6 Promotion of Pupils’ Commitment and Actions for a Future Sustainable Life

In the interviews, pupils mentioned the future commitment and actions for a sustainable life. Positive commitments were found in groups 1 and 2 (PRB only and PRB with poster intervention respectively). Pupils could describe the details of their commitment and wanted to perform better so that they can protect the environment. They therefore sought solutions to collecting the plastic wastes from school and even home, and dropped them into the PRB provided.

I will take the plastic wastes from home to school and discard them in the PRB. [Pupil F from Group 1]

I want to protect the earth. [Pupil G from Group 1]

After the lessons, I want to actively participate in plastic recycling. Before, I thought that it was difficult so I did not do it. Now I think that it is quite easy and convenient, and I can do it whenever I can, so I will do it when I have time (to approach the PRB). [Pupil H from Group 2]

I want to participate more and perform the 4-steps properly as I don’t want to see the end of the world approaching. [Pupil I from Group 2]

Interestingly, pupils from groups 3 and 4, who were using the BB with or without posters respectively, showed a rather passive response towards future commitment to a sustainable life. Thus, together with the data shown in the previous paragraphs, recycling competence requires proper education, promotion, and a suitable tool to evoke the pro-environmental outcomes.

I will spend more time noticing the type of plastic wastes that belongs to…[Pupil J from Group 3]

I did not use the brown bin because I am lazy. …[Pupil K from Group 4]

I did not know the location of the brown bin so I did not use it. [Pupil L from Group 4]

4.7 Improved Recycling Qualities Using PRB

The status of plastic waste served as the evidence of action competence in plastic waste recycling, indicating a better performance of pupils from schools using the PRBs in terms of the recycling parameters. SEP and COM were significantly improved in schools using the PRB (p < 0.005). Although there were no significant differences in CLE, a higher percentage of plastic waste from those schools using the PRBs was cleaner (62.85% > 56.94% for brown bin schools, excluding the baseline data) (Table 10.5).

As for plastic waste sorting accuracy, the plastic waste was checked for the correct type in each plastic compartment of the PRBs each week. The polyethylene terephthalate (PET) compartment’s sorting accuracy was similar for the two groups with or without intervention (Fig. 10.2). The total amount of plastic waste collected from group 2 (PRB with poster invention) was higher than that from the group 1 (PRB only) schools, at 1.66 kg/week versus 1 kg/week, respectively with p = 0.066 (One-way ANOVA). Although the result was not yet significant, the PRB with intervention could attain a higher usage rate.

5 Discussion

5.1 Effective Recycling Program Using the PRB in Combination with Intervention

Through incorporating the school-based action competence approach into the program design for plastic waste recycling in schools, the program successfully enhanced pupils’ learning of plastic waste recycling, especially with the use of the PRB and the interventions to sustain pupils’ intention and behavior to use the bin properly. As reflected in the improved plastic waste data, the PRB with interventions strengthened the pupils’ sorting accuracy of plastic waste, which is attributable to the additional sources of information provided by the posters. Plastic knowledge of classifying plastic types was significantly enhanced, which may facilitate their waste handling process. The PRB also enhanced the behaviours among pupils, such as recycling the plastic waste by type and performing the recycling steps in advance, as they found that putting the plastic waste into the corresponding compartment was interesting. Besides, a higher proportion of plastic waste was found to be separated and compressed after using the PRB. More importantly, this provided an opportunity for pupils to practise the recycling action. On the other hand, use of the BBs may have discouraged the pupils from performing 4-step recycling, especially the classification, even though they understood the recycling principles and knowledge better after the interventions, as the BBs only contain one compartment which makes it meaningless to further process the plastic waste before discarding it. In comparison, the PRB contains eight compartments that allow pupils to discard their plastic waste according to type, providing practical meaning for classifying the waste in advance.

Interestingly, it is observed that there were very mild increases in the pupils’ KAB after joining the program as a whole compared with the starting survey. Similar results were also reported by Goodwin et al. (2010) that school pupils tend to raise their pro-environmental attitudes a little after knowing their school has participated in green programs (a Hawthorne-type effect). The face-to-face interviews allowed the research team to understand the pupils’ pro-environmental attitudes in more detail. The interviews reflected that pupils from the treatment groups were quite positive about the use of the PRB. The PRB further encouraged the pupils’ recycling methods, and gave them opportunities to practice the actions.

5.2 Importance of a Strategic Intervention in Plastic Recycling

5.2.1 Promotion of Direct Environmental Actions

Application of the PRB in primary schools is practical and meaningful for improving plastic recycling as a direct activator. Pupils could experience new ways of recycling by understanding the types of plastics and performing the 4-step recycling procedure. The present study reveals that the initial step to change the behavior of plastic recycling requires a tailor-made recycling bin (PRB) as an education tool, and interventions. The PRB can be an education tool to fill the gap in the teacher’s guide book published by the Environmental Protection Department (2011). Thus, installing recycling bins and adopting appropriate strategies can positively direct environmental action. In a college campus recycling intervention designed by Largo-Wight et al. (2013), it was found that an increase in recycling bins largely and significantly encouraged the recycling outcome. With the PRB, pupils can now sort the plastic types and discard them into their corresponding compartment for storage. This is an environmental action for solving the poor condition of plastic waste in recycling bins and maintaining its recyclable value.

To guide pupils to use the PRB, poster displays are treated as a low cost and technical intervention but with positive effects in many recycling campaigns (Cole & Fieselman, 2013; Delprato, 1977; Kalsher, Rodocker, Racicot, & Wogalter, 1993). Information provided by the posters can be declarative, such as the plastic types and examples of plastic waste, or can be procedural-oriented such as showing the recycling steps based on the classification of Gagne, Yekovich, and Yekovich (1993). Iyer and Kashyap (2007) supported that both information types are effective in terms of influencing recycling performance, which is more practical than using incentive strategies. Yet, the location of the posters should be installed in eye-catching and easy-to-reach locations for positive outcomes (Geller, Chaffee, & Ingram, 1975). Therefore, the posters were posted in every classroom of the assigned schools as prompts and a source of information to remind pupils of the four proper steps of plastic waste recycling. Posters were also posted next to the PRBs, which made them convenient for the bin users to perform the recycling steps immediately before discarding their recyclables. Since a single intervention with a poster may not be effective for the ultimate goal of the program, as pupils had to approach the poster to read the information, a thorough knowledge base of plastic waste management will help sustain the proper recycling behaviors in the longer term (Iyer & Kashyap, 2007).

5.2.2 Creating Educational Contexts for Indirect Environmental Actions

Green training courses were conducted in the treatment schools in addition to the poster intervention to further strengthen the pupils’ KAB of plastic recycling. They could then help spread the green messages to others. In the interviews, the pupils reflected that they shared what they had learnt from the training course with others, but the spillover effect still has room for improvement in the primary school setting. However, combining the interventions with the use of the PRB, both strategies could enhance the recycling outcome observed in the present study.

5.3 Limitations of the Present Study

It was shown that pupils from the schools using the PRBs with or without intervention were already very good in terms of their pro-environmental attitudes. A more significant level of enhancement in attitudes may require greater efforts for their attainment. Smeesters, Warlop, and Abeele (2001) considered that attitudes are stable characteristic features of every person and may not be easily changed. Thus, a 3-week intervention and the presence of the PRBs may not be sufficient for promoting attitude changes among pupils, as reflected in the NEP. Besides, due to the limitation of time and space, the training course was only open to a certain quota of pupils (70 pupils/school) in the hope of providing intensive training for the pupils as green ambassadors.

To further promote proper plastic recycling, PRBs can be installed in different locations such as secondary schools, university or college dormitories, offices, shopping malls, or housing estates. However, effective promotion schemes have to be studied as different locations target different users. To engage more people of different backgrounds in using the PRBs, interventions and the action competence approach are worth investigating to promote recycling. Education does exert a great influence on improving the environment and nurturing a sustainable future by promoting action competence for a green lifestyle. The present study encourages environmental educators to develop and justify the strategies of the surrounding environmental issues and put them into practical educational use, with positive action as feedback.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy. New York: Longman Publishing.

Cheng, N. Y. I., & So, W. M. W. (2015). Environmental governance in Hong Kong—Moving towards multi-level participation. Journal of Asian Public Policy, 1–15.

Chow, C. F., So, W. M. W., & Cheung, T. Y. (2016). Research and development of a new waste collection bin to facilitate education in plastic recycling. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 15, 45–57.

Chow, C. F., So, W. M. W., Cheung, T. Y., & Yeung S. K. D. (2017). Plastic waste problem and education for plastic waste management. emerging practices in scholarship of learning and teaching in a digital era. In S. C. Kong, T. L. Wong, M. Yang, C. F. Chow, & K. H. Tse (Eds.), Emerging practices in scholarship of learning and teaching in a digital era (pp. 125–140). Singapore: Springer.

Chung, S. S., & Poon, C. S. (2001). A comparison of waste-reduction practices and new environmental paradigm of rural and urban Chinese citizens. Journal of Environmental Management, 62, 3–19.

Cincera, J., & Krajhanzl, J. (2013). Eco-schools: What factors influence pupils’ action competence for pro-environmental behaviour? Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 117–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.06.030.

Clean Authority of Tokyo. (2017a). Towards a recycling-oriented society. Waste report (23 2018). Retrieved from http://www.union.tokyo23-seisou.lg.jp/seiso/seiso/pamphlet/report/documents/gomirepoepdf.pdf.

Clean Authority of Tokyo. (2017b). Business summary (2017 version), pp. 13. Retrieved from http://www.union.tokyo23-seisou.lg.jp/kikaku/kikaku/kumiai/shiryo/documents/29_jigyougaiyou_p13~15.pdf.

Cole, E. J., & Fieselman, L. (2013). A community‐based social marketing campaign at Pacific University Oregon. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371311312888.

Curriculum Development Committee (CDC). (1999). Guidelines on environmental education in schools. Hong Kong: The Education Department.

Damerell, P., Howe, C., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2013). Child-orientated environmental education influences adult knowledge and household behaviour. Environmental Research Letters, 8(1), 015016.

Delprato, D. J. (1977). Prompting electrical energy conservation in commercial users. Environment and Behavior, 9(3), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657700900307.

De Young, R. (2000). New ways to promote proenvironmental behavior: Expanding and evaluating motives for environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3). Wiley-Blackwell (pp. 509–526). https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00181.

Department of Environmental Protection, Taipei City Government. (2017). Retrieved from https://www-ws.gov.taipei/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9VcGxvYWQvMzYzL3JlbGZpbGUvMTg2NTIvNzM0MTc5OS9hNmU5YWJhNy1lNDU4LTQ3ZDUtYTVhMi1hN2VkMTY4MWI4MDEucGRm&n=NzUtMTA25bm0MTLmnIjlnoPlnL7ph48ucGRm.

Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The new environmental paradigm. The Journal of Environmental Education, 9(4). Informa UK (pp. 10–19). https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1978.10801875.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2000). New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176.

Environmental Protection Department. (2011). Reduce your waste and recycle your plastics campaign teachers’ guidebook (p. 20). Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Environmental Protection Department. (2016). Monitoring of solid waste in Hong Kong: Waste statistics for 2016. Retrieved from https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/sites/default/files/msw2016.pdf.

Environmental Bureau. (2013). Environmental blueprint for sustainable use of resources 2013–2022. The Hong Kong Government. Retrieved May 20 from http://www.enb.gov.hk/en/files/WastePlan-E.pdf.

Evans, G. W., Brauchle, G., Haq, A., Stecker, R., Wong, K., & Shapiro, E. (2007). Young children’s environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 39(5), 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506294252.

Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan). (2017a). Environmental protection administration, properties of municipal solid waste. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov.tw/site/epa/public/MMO/EnvStatistics/c4020.pdf.

Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan). (2017b). Environmental protection administration, disposal of municipal solid waste. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov.tw/site/epa/public/MMO/EnvStatistics/c4010.pdf.

Gagné, Ellen D., Yekovich, C. W., & Yekovich, F. R. (1993). The cognitive psychology of school learning (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins College Publishers.

Geller, E. S., Chaffee, J. L., & Ingram, R. E. (1975). Promoting paper recycling on a university campus. Journal of Environmental Systems, 5(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.2190/e2lm-jntv-nbj6-etjf.

Goodwin, M. J., Greasley, S., John, P., & Richardson, L. (2010). Can we make environmental citizens? A randomised control trial of the effects of a school-based intervention on the attitudes and knowledge of young people’. Environmental Politics, 19(3), 392–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644011003690807.

Gottlieb, D., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Haim, A. (2013). Encouraging ecological behaviors among students by using the ecological footprint as an educational tool: A quasi-experimental design in a public high school in the city of Haifa. Environmental Education Research, 19(6), 844–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.768602.

Hiramatsu, A., Kurisu, K., Nakamura, H., Teraki, S., & Hanaki, K. (2014). Spillover effect on families derived from environmental education for children. Low Carbon Economy, 5(2), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.4236/lce.2014.52005.

HKSAR Gov’t. (2013). LCQ19: Three-colour waste separation bins. [Press release]. Retrieved February 27, 2013, from http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/ge-neral/201302/27/P201302270298.htm.

Hopewell, J., Dvorak, R., & Kosior, E. (2009). Plastics recycling: Challenges and opportunities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1526), 2115–2126. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0311.

Hungerford, H. R., & Volk, T. L. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 21(3), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1990.10753743.

IBM Corp. (2012). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Iyer, E. S., & Kashyap, R. K. (2007). Consumer recycling: Role of incentives, information, and social class. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.206.

Jensen, B. B. (2002). Knowledge, action and pro-environmental behaviour. Environmental Education Research, 8(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145474.

Jensen, B. B., & Schnack, K. (1997). The action competence approach in environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 3(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462970030205.

Kalsher, M. J., Rodocker, A. J., Racicot, B. M., & Wogalter, M. S. (1993). Promoting recycling behavior in office environments. Human factors and ergonomics society. Paper presented at the 37th Annual Meeting, October (pp. 484–488). https://doi.org/10.1177/154193129303700703.

Kopnina, H. (2014). Future scenarios and environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 45(4), 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2014.941783.

Largo-Wight, E., Johnston, D. D., & Wight, J. (2013). The efficacy of a theory-based, participatory recycling intervention on a college campus. Journal of Environmental Health, 76(4), 26–31 6p. CINAHL with Full Text, EBSCOhost (Accessed November 18, 2015).

Lee, J. C. K. (2000). Teacher receptivity to curriculum change in the implementation stage: The case of environmental education in Hong Kong. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 32(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202700182871.

Lee, S., & Paik, H. S. (2011). Korean household waste management and recycling behavior. Building and Environment, 46(5), 1159–1166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.12.005.

Manoli, C. C., Johnson, B., & Dunlap, R. E. (2007). Assessing children’s environmental worldviews: Modifying and validating the new ecological paradigm scale for use with children. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3200/joee.38.4.3-13.

Ministry of Environment, Environmental Statistics Yearbook 2014. (2014). Retrieved from http://eng.me.go.kr/eng/web/board/read.do?pagerOffset=0&maxPageItems=10&maxIndexPages=10&searchKey=&searchValue=&menuId=29&orgCd=&boardId=497370&boardMasterId=548&boardCategoryId=&decorator.

Mobley, C., Vagias, W. M., & DeWard, S. L. (2009). Exploring additional determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: The influence of environmental literature and environmental attitudes. Environment and Behavior, 42(4), 420–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508325002.

Mogensen, F. (1997). Critical thinking: A central element in developing action competence in health and environmental education. Health Education Research, 12(4), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/12.4.429.

Plastic Waste Management Institute. (2014). An introduction to plastic recycling. Retrieved from https://www.pwmi.or.jp/ei/plastic_recycling_2016.pdf.

Pol, E., & Castrechini, A. (2014). Disruption in education for sustainability? Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 333. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.v45i3.1477.

Rickinson, M. (2001). Learners and learning in environmental education: A critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research, 7(3), 207–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620120065230.

Roczen, N., Kaiser, F. G., Bogner, F. X., & Wilson, M. (2013). A competence model for environmental education. Environment and Behavior, 46(8), 972–992. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513492416.

Seatter, C. S. (2011). A critical stand of my own. Complementarity of responsible environmental sustainability education and quality thinking. The Journal of Educational Thought, 45(1), 21–58.

Smeesters, D., Warlop, L., & Abeele, P. V. (2001). The state-of-the art on domestic recycling research. Final Report of Scientific Support Plan for a Sustainable Development Policy (SPSD 1996–2001). The Federal Office for Scientific, Technical and Cultural Affairs (OSTC).

So, W. M. W., Cheng, N. Y. I., Chow, C. F., & Zhan, Y. (2016). Learning about the types of plastic wastes: effectiveness of inquiry learning strategies. Education 3–13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 44, 311–324.

Taipei City Government, Demographic Overview. (2017). Retrieved from https://english.gov.taipei/cp.aspx?n=C619997124A6D293.

Tam, V. W. Y., & Tam, C. M. (2006). Evaluations of existing waste recycling methods: A Hong Kong study. Building and Environment, 41(12), 1649–1660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.06.017.

Zelezny, L. C. (1999). Educational interventions that improve environmental behaviors: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education, 31(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969909598627.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by donations from the Lam Foundation (Project No. E0354) and The Hong Kong Bank Foundation (Project No. C1041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix 1: Detail of the Plastic Classification of the PRB (EPD, 2011)

Plastic types | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

1. | PET | Soft drink, water bottles |

2. | HDPE | Detergent or juice bottles |

3. | PVC | Disinfectant container, pipes, shower curtains or plastic labels |

4. | LDPE | Packaging or plastic bags |

5. | PP | Liquid containers, folders or cups |

6. | PS | CD cover, live lactobacillus drink bottles or foam container |

7. | Others | Toys, nylon, pump dispensers |

8. | Blended polymer | Plastics with other materials blended |

Appendix 2: Pupils’ General Knowledge of Waste Management

Pre-test | Post-test 2 | Pair-T test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

General knowledge | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | N | t | Sig. |

How many current operating landfill sites are there in Hong Kong? | 0.850 | 0.358 | 0.853 | 0.355 | 313 | 0.132 | 0.895 |

Which of the following is/are the source(s) of municipal solid waste in Hong Kong? | 0.586 | 0.493 | 0.589 | 0.493 | 309 | 0.093 | 0.926 |

In which of the following time periods is the SENT Landfill site in Tseung Kwan O expected to reach saturation? | 0.324 | 0.469 | 0.295 | 0.457 | 312 | −0.943 | 0.346 |

According to the waste hierarchy, which of the following should be the first priority? | 0.365 | 0.482 | 0.436 | 0.497 | 312 | 2.018 | 0.044* |

According to the government plan of SENT Landfill site expansion, which of the following types of land is planned to be used? | 0.180 | 0.385 | 0.213 | 0.410 | 300 | 1.179 | 0.239 |

Appendix 3: Interview Questions

-

(a)

Compulsory questions

-

1.

How do you know about different types of plastic?

-

2.

After joining this program, did you spend extra time understanding more about plastic recycling, classification and the 4 steps of recycling?

-

3.

In your opinion, what threats would plastic waste pose to the environment?

-

4.

Do you want to participate more in plastic classification and the 4 steps of recycling?

-

1.

-

(b)

For schools with posters

-

5.

Is the poster design appealing to you? (1–5 marks, 5 marks = very appealing)

-

6.

Did the poster help you to know more about plastic classification?

-

7.

Can you comment on our poster? Any improvements needed? (can show the poster)

-

5.

-

(c)

For schools with PRB

-

8.

Have you ever used the PRB recycling bins on campus? (if yes) Did you read the recycling hints on the boxes (i.e., the 4 Recycling Steps) before recycling?

-

9.

Have you faced any difficulties when using the PRB recycling bins?

-

8.

-

(d)

For schools with Brown bins

-

10.

Have you ever used the brown plastic recycling bin? (if yes) Did you do the 4 recycling steps before recycling rubbish? Why or why not?

-

11.

Have you faced any difficulties when using the Brown bins?

-

10.

Appendix 4: Pupils’ Knowledge of Types of Plastic Waste

Correct type | Plastic items | Pre-test | Post-test 2 | Pair-T test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean | SD | Mean | SD | N | t | Sig. | ||

4 | Plastic bag | 0.094 | 0.292 | 0.100 | 0.300 | 310 | 0.308 | 0.758 |

2 | Cleaning product bottle | 0.162 | 0.369 | 0.152 | 0.360 | 309 | −0.366 | 0.715 |

1 | Disposable water bottle | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0.127 | 0.334 | 307 | −1.251 | 0.212 |

4 | Plastic wrap/cling film | 0.065 | 0.246 | 0.152 | 0.360 | 309 | 3.647 | 0.000** |

6 | Styrofoam takeaway box | 0.035 | 0.185 | 0.061 | 0.240 | 311 | 1.515 | 0.131 |

7 | CD | 0.103 | 0.304 | 0.100 | 0.300 | 311 | −0.135 | 0.893 |

5 | Disposable straws | 0.049 | 0.215 | 0.065 | 0.246 | 309 | 0.845 | 0.399 |

5 | Disposable water bottle cap | 0.074 | 0.263 | 0.078 | 0.268 | 309 | 0.156 | 0.876 |

3 | Credit card | 0.049 | 0.216 | 0.078 | 0.269 | 307 | 1.621 | 0.106 |

3 | Shower curtain | 0.081 | 0.273 | 0.065 | 0.246 | 309 | −0.780 | 0.436 |

1 | Soft drink bottle | 0.126 | 0.333 | 0.113 | 0.317 | 309 | −0.516 | 0.606 |

7 | Nylon bag | 0.061 | 0.240 | 0.116 | 0.321 | 310 | 2.557 | 0.011* |

6 | Lactic acid bacteria drink bottle | 0.048 | 0.215 | 0.114 | 0.317 | 311 | 3.099 | 0.002** |

4 | Food storage bags | 0.039 | 0.194 | 0.078 | 0.268 | 308 | 2.069 | 0.039* |

Appendix 5: Scope of Attitude and Perceived Behavior Measurement

Attitude (Eco-crisis) (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree) |

Q1 There are/will be too many people living on earth now/in the future. Q2 Plants and humans have the same right of survival Q3 Humans are destroying the natural environment Q4 Humans have sufficient wisdom to prevent the decay of the earth Q5 Humans have to follow the rules of nature Q6 Humans destroy the nature will bring up bad consequences Q7 The natural environment have the sufficient power to reverse the problems created by the humans in morden daily life Q8 Humans are the master of all things Q9 Humans will understand the principles of the nature and be capable to control the natural environment Q10 There will be great natural disasters if the situation is not improved |

Perceived behavior (1 = never to 5 = always) |

Q1 I will remove the cap and package of the plastic bottle before discarding it into the recycling bin Q2 I will remove the residue drinks and wash the plastic bottle before discarding it into the recycling bin Q3 I will compress the plastic waste (if compressible) before discarding it into the recycling bin Q4 I will remove the non-plastic parts of the plastic waste (e.g., price tags) before discarding it into the recycling bin Q5 I aware of different texture of plastic wastes Q6 I will tie a lot or compress the plastic bag before discarding it into the recycling bin Q7 Most of my rubbish/wastes are made from plastics Q8 When processing rubbish/wastes, I will sort the plastic waste out for recycling |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Cheang, C.C. et al. (2019). Enhancing Pupils’ Pro-environmental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours Toward Plastic Recycling: A Quasi-experimental Study in Primary Schools. In: So, W., Chow, C., Lee, J. (eds) Environmental Sustainability and Education for Waste Management. Education for Sustainability. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9173-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9173-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-9172-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-9173-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)