Abstract

In language assessment, the assessors often need to judge whether certain language forms produced by students are correct or acceptable. This seemingly easy procedure may be at stake in situations where the de jure language standard is unspecified. Drawing upon the challenges we encountered in developing proficiency descriptors for Chinese language (CL) in Singapore, this study attempts to examine the impact and implications of lacking an officially endorsed standard and norm for CL education and assessment. To resolve the dilemmas in pedagogy and assessment, we suggest that the value of the indigenized CL variety be recognized and more focus be put on communicative competency rather than language forms. Understanding language tests and their effects involves understanding some of the central issues and processes of the whole society, and thus, decision makers have to be well versed in sociolinguistics and be able to elaborate on the consequences of tests in broader sociopolitical settings.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the development and utilization of proficiency descriptors (or proficiency scales) as a guidance and/or benchmark in language learning and teaching (e.g., Fulcher et al. 2011). Some well-received language proficiency descriptors developed in worldwide context include, among many others, the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) , American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) guidelines , World-class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA) , PreK-12 English Language Proficiency Standards, and Canadian Language Benchmarks (CLB) . These endeavors correspond with the call for a performance-based assessment , which emphasizes the evaluation of learners’ ability to apply content knowledge to critical thinking, problem solving, and analytical tasks in the real world throughout their education (Rudner and Boston 1994; Darling-Hammond and McCloskey 2008). Language proficiency descriptors usually consist of a successive band of descriptions of the language knowledge and skills learners are expected to attain at certain learning stages. These descriptors are established to reflect the language learners’ real-life competencies or interaction abilities (Bachman 1990) and are intended to be instrumental in identifying language learners’ proficiency levels and helping teachers consistently assess and track students’ learning progression. As encapsulated by North and Schneider (1998), proficiency descriptors or scales can be used to fulfill a number of functions, such as to provide “stereotypes” for learners to evaluate their position or to enhance the reliability of subjectively judged ratings with a common standard and meaning for such judgments. In other words, a common metric or yardstick enables comparison between systems or populations. Owing to the proliferation of potential pedagogical benefits, numerous language proficiency descriptors have been developed worldwide. With carefully established proficiency descriptors, the operationalization of classroom authentic assessment of language proficiency in a specific language-in-use context is becoming more target-oriented.

In general, proficiency level descriptors are designed to show the progression of second language acquisition from one proficiency level to the next and serve as a road map to help language teachers to instruct content commensurate with students’ linguistic needs. Language learners may exhibit different proficiency levels within the domains of listening, speaking, reading, and writing. In the development of proficiency descriptors, the linguistic competence , namely the knowledge of, and ability to use, the formal resources to formulate well-formed, meaningful messages (Council of Europe 2001), is one of the key components to be scaled. This competence sets out to define learners’ phonological , orthographic , semantic , lexical, and grammatical knowledge of the target language as well as their ability to use them accurately and properly. For example, the language outputs of advanced learners are expected to be closely approximate to the standard forms or conventions, thus the descriptors for this proficiency level tend to contain descriptions such as “free of error” and “consistently correct.”

However, the linguistic competence can become an intricate part of the development of proficiency descriptors as well as in the implementation of assessment due to the nature of the language tests as a social practice (McNamara 2001). Many scholars in recent years have pointed out the complex link between language policies and standardized testing . Shohamy (2007), for instance, notes that “the introduction of language tests in certain languages delivers messages and ideologies about the prestige, priorities and hierarchies of certain language(s)” (p. 177). This is because when the assessment framework is used to determine the educational outcomes, the tests have an “encroaching power” in influencing national language policy (McNamara 2008). That is, the criteria of proficiency descriptors used for judging language competence via rating scales would inevitably bring about sociopolitical ramifications. Unfortunately, the social and political functions of tests “are neglected in most of the texts on language testing” (McNamara 2008, p. 416).

As a guide for language assessment, proficiency descriptors are supposed to define clearly the achieving standards for each key stage. However, there are cases where the establishment of specific standards can be a hard decision to make due to the tremendous sociopolitical implications that they may engender. In this chapter, we look into the development of Chinese language (CL) proficiency descriptors in Singapore, a polity renowned for its linguistic diversity, with a purpose to demonstrate how language assessment can be thwarted by the tensions between language use and language standard.

Focusing on the percept-practice gap in the development of proficiency descriptors, this chapter examines the challenges in setting up standards for second language assessment in a politically sensitive society in order to showcase the effect of tacit language policy on language assessment. The organization of this chapter is as follows. We begin by offering a brief introduction to the sociolinguistic milieu in Singapore and the rationale of developing curriculum-based CL proficiency descriptors . Then, we present some entrenched usages of Singaporean Mandarin in students’ output, on which CL proficiency descriptors are based. Next, we provide a discussion of the difficulties we encountered in the development of CL proficiency descriptors and an elaboration of the challenges these difficulties may pose in CL teachers’ instructional practice from the perspective of language acquisition planning . Finally, possible solutions are proposed to overcome any pedagogical dilemmas that may be caused by the lack of universally accepted assessment criteria. The concluding section critically reflects on the implications of Singapore experience for the assessment and other relevant issues in other places of the Chinese-speaking world and beyond.

Developing CL Proficiency Descriptors in Singapore: Background and Rationale

In Singapore, in order to provide an evaluative instrument with comparability across schools and eventually to replace the more traditional school-based tests , a set of Mother Tongue Language (MTL) proficiency descriptors has been developed recently as a common reference for learners, teachers, curriculum planners, and assessment officers. In this way, MTL learning expectations can be better defined and goals of attainment more easily gauged (MTLRC 2011). In this section, the rationale and process of developing proficiency descriptors are illustrated in detail.

Singapore’s Language Environment and Education

Singapore is a multiracial and multilingual city state in Southeast Asia. It has a total population of 5.47 million, of which Chinese, Malays, Indians, and others account for 74.26, 13.35, 9.12, and 3.27%, respectively (Department of Statistics 2014). English, Mandarin, Malay, and Tamil are established as four official languages, with English being the working language as well as the lingua franca of the residents, and the other three being the designated mother tongues of the major ethnic groups. In light of its bilingual education policy, all school students must learn English as the first language and their mother tongue languages (MTLs) as second languages, despite their bona fide linguistic backgrounds.

In view of the dominant role and overriding significance of English in the society, the past two decades have witnessed a marked and steady change of frequently used home language from mother tongues to English in Singapore. For instance, a survey conducted by the Ministry of Education (MOE) showed that ethnic Chinese students with English as the most frequently used home language increased from 28% in 1991 to 59% in 2010 (MTLRC 2011). This rapid home language shift has brought about far-reaching implications for MTL education (Zhao and Liu 2010). To ensure MTL education, including CL education, continues to stay relevant to learners’ daily life and effective in teaching approaches, the MOE has reviewed and reformed the MTL curriculum and pedagogy on a periodic basis. In the latest endeavor, the MTL Review Committee, commissioned by the MOE in January 2010, conducted a comprehensive evaluation of MTL teaching and testing in Singapore schools, and thereafter proposed some practical recommendations to enhance MTL education. One of the key recommendations made by the MTL Review Committee was to develop proficiency descriptors to aid teachers in aiming for observable outcomes in teaching, and also to motivate students at different learning stages to progress accordingly (MTLRC 2011, p. 13).

MTL Proficiency Descriptors: What and Why

There has been an agreed-upon belief among language educators and scholars that the expectations of learners should be stated clearly at different phases of learning so that teaching, learning, and assessment can be well guided (Wang et al. 2014). In view of this, proficiency descriptors for each of the three MTLs in Singapore were recommended to be developed by educational authorities. This recommendation on developing proficiency descriptors also tallies with a major objective of MTL education, i.e., to develop proficient users who can communicate effectively using the language in authentic contexts and apply it in interpersonal communication , as highlighted in MTLRC (2011). Through school curriculum, students are expected to learn to apply and use MTL in their lives, and these expectations need to be scoped into clearly defined performance objectives at progressive levels.

In order to spell out the attainment goals for a wide range of real-life communications, proficiency descriptors of six core language skills in MTL, namely listening , speaking , reading , writing , spoken interaction , and written interaction ,Footnote 1 have been articulated by the curriculum officers at MOE. The introduction of interaction (spoken and written) descriptors is based on the fact that many real-life situations require spontaneous two-way interaction (e.g., listening and responding orally during a conversation or reading and responding in written form such as an e-mail). To help students cope with communication in such interactive settings, it is necessary for school curriculum to emphasize spoken and written interaction skills to enhance their ability to use the language meaningfully and effectively in daily communications.

The MTL proficiency descriptors can fulfill three purposes, as indicated in MTLRC (2011). First, the proficiency descriptors can help MTL teachers target observable outcomes and tailor their teaching, classroom activities, and assessments to create more opportunities for students to practice and use their MTLs in specific ways. With clearer goals for students to achieve, the teachers can also implement new instructional materials and learning resources based on the proficiency descriptors . Second, for the students, the breaking down of goals can bolster their confidence and inspire their learning. Proficiency descriptors spell out more explicitly the language skills and levels of attainment students should achieve at various key stages of learning. With clearer goals, learners can be better motivated to progress from one level to the next. In addition, in the proficiency descriptors , the use of everyday situations and contexts, current affairs, and contemporary issues as well as authentic materials (e.g., reports and news articles) will provide real-world context for classroom learning. This will allow students to see the relevance of MTLs in their daily lives and enable them to achieve practical language competence. Third, MTL assessments will be better targeted. With proficiency descriptors serving as an array of definite progressive criteria, assessments can be aligned with the content and objectives of the curriculum.

Development of Chinese-Speaking Proficiency Descriptors

The development of the MTL proficiency descriptors Footnote 2 was undertaken by the Curriculum Planning and Development Division (CPDD) of MOE from 2011 to 2014 (Wang et al. 2014). As CPDD’s collaborators, the two authors were commissioned to lead a research team to conduct a project that aimed to develop proficiency descriptors for CL speaking and oral interaction . Since speaking and interaction are two closely related oral skills and the proficiency descriptors development processes are similar, for sake of convenience, we hereafter just focus on the development of CL speaking proficiency descriptors, which encapsulate CL learners’ ability to communicate orally in clear, coherent, and persuasive language appropriate to purpose, occasion, and audience.

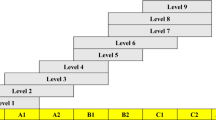

As part of our effort to develop CL speaking proficiency descriptors , Singaporean Chinese students with average CL speaking aptitudeFootnote 3 at some key learning stages from elementary and secondary school to junior college or high school (e.g., primary 2, primary 4, primary 6, and secondary 2; or Grades 2, 4, 6, and 8) were selected to perform a diverse range of speaking tasks as a means of soliciting oral speech, such as show-and-tell, picture description, and video description/comment. The speaking activities were video-recorded, and thereafter, some video clips containing performances commensurate to specific speaking levels were transcribed and linguistic features were analyzed in detail. Based on the students’ performance, nine levels of proficiency descriptors were developed for CL speaking skills. The speaking proficiency descriptors comprise a scale of task-based language proficiency descriptions about what individual learners can speak in spontaneous and non-rehearsed contexts and serve as a guide to the teaching and assessment of CL learners over the course of 12 years (from Primary 1 or Grade 1 to Junior College 2nd year or Grade 12) in Singapore. They describe CL learners’ successive levels of speaking achievement. After the proficiency descriptors for CL speaking were established, a validation session was administered by MOE among CL practitioners, and for a reference purpose, two to three video clips were selected as exemplars of each speaking level (for more about the sampling process and project implementation, please see Wang et al. 2014). Now, the CL proficiency descriptors have been incorporated in the new CL syllabus (CPDD 2015), serving as a guide for curriculum development, teaching, and assessment.

In the formulation of specific performance levels, a range of well-recognized proficiency descriptors or scales, such as HSKK (Hanyu Shuiping Kouyu Kaoshi or Oral Chinese Proficiency Test) (see Teng, this volume), CEFR , ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines (see Liu, this volume), were closely referenced. In the established CL speaking proficiency descriptors , five aspects of speaking competence have been factored into the assessment: topic development, organization, vocabulary, grammar, and articulation, with the latter three concerned with language forms. In terms of vocabulary, frequency level of words featured in a student’s discourse was taken as an indicator of vocabulary advancement. For instance, the vocabulary used by lower level speakers was mainly confined to high-frequency words. For higher level speakers, they tended to use a significant amount of low-frequency or advanced vocabulary, and the use of rhetoric devices such as idiomatic language or figures of speech was also expected. A mix of high-frequency and lower frequency words typically would appear in medium level speakers’ oral discourse. Grammatically, the use of simple or complex sentence structures was the major criterion. With the progression of speaking competence , students’ sentence structures would become more syntactically complicated. For articulation, the dimensions that were scaled included correctness of pronunciation and intonation and naturalness and fluency of speech. For instance, with respect to naturalness and fluency of speech, lower level speakers would have many pauses, whereas higher level speakers could present more naturally and fluently.

A keen awareness we fostered in the process of developing the speaking CL proficiency descriptors was that proficiency descriptors formulated by educational experts, researchers, and teaching professionals must be customized to accommodate Singaporean students’ abilities and learning needs. In this regard, one crucial factor that held sway in the development process was students’ actual language practice in Singapore’s Mandarin-speaking environment. In the next section, we examine some language use features of Huayu (i.e., Singapore Mandarin ) that constituted an important basis on which we considered the relevance and adequacy of speaking proficiency descriptors to Singapore students. Through the discussion of the differences between Huayu and Putonghua (standard Mandarin in Mainland China), we aim to unravel the importance of attending to issues of what standard and whose standard in CL assessment, in particular, the discrepancies that often exist between what is imposed through language policy making and how language is actually used in the society.

Huayu Usage in Spoken Language: Students’ Output

Huayu and Its Subvarieties

Huayu is a term used in Singapore to refer to Mandarin, the designated mother tongue of Singaporean Chinese. Huayu is often recognized as a new variety of Modern Chinese developed in Singapore’s particular pluralinguistic environment (Chew 2007; Shang and Zhao 2013; Wang 2002). It is a unique product of its long-term close contact with different languages, such as English, Malay, and various Chinese regionalects. In the early years after Singapore’s independence, most ethnic Chinese Singaporeans spoke Southern Chinese dialects , e.g., Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka, and Hainanese, which were mutually unintelligible. Mandarin, which features totally different pronunciations from the regional dialects, was merely a minority CL variety with relatively few native speakers in Singapore then. In order to facilitate communicative intelligibility among different dialectal groups and to create an environment conducive for children’s CL learning, the government launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, which has institutionalized as an annual event to promote the use of Mandarin (Bokhorst-Heng 1999; Newman 1988). In light of this initiative, many dialect speakers have switched to Mandarin as their most oft-used home language. However, the dialects, as substratum languages, have exerted continuous influence on the Mandarin that Chinese Singaporeans are using. In addition, due to its constant contact with English, the language of wider communication in the country, Huayu has also incorporated some linguistic features of English. Generally speaking, Huayu is similar to other Chinese varieties, such as Putonghua in Mainland China and Guoyu in Taiwan, though it has some idiosyncratic linguistic features that make it distinct from other Chinese varietiesFootnote 4.

In fact, Huayu , as a new variety of Modern Chinese, is a heterogeneous variety in itself. Based on the widely cited postcreole continuum in sociolinguistics (Platt and Weber 1980), three subvarieties of Huayu can be identified according to their linguistic convergence with Putonghua: acrolect , basilect and mesolect .Footnote 5 The acrolect is closely approximate to Putonghua in all linguistic aspects; it is typically found in CL textbooks, mass media, and print publications and used by most highly proficient CL speakers in formal contexts. Except for some lexical items uniquely found in Singapore, the phonology , vocabulary , and grammar of the acrolect of Huayu are in compliance with the Putonghua norm. In news broadcasting, for instance, except some vocabulary signifying items of local reference (e.g., Zuwu signifying government-constructed economic flats, Yongchezheng signifying the license to own a car), language forms of Huayu are nearly indiscernible even for Putonghua speakers from Mainland China . Undeniably, one reason for this is that a number of the Chinese newscast anchors in MediaCorp, the official broadcasting company in Singapore, are immigrants from Mainland China. When it comes to CL textbooks, it is found that many retroflex ending sounds, which Singaporeans rarely produce in their oral language, are actually annotated (Shang and Zhao 2013).

The basilect Huayu , by contrast, is the variety that diverges most from Putonghua . It is not only heavily accented by dialectal usages, but also characterized by frequent code switching and heavy code mixing between Mandarin and dialects , English, Malay, and so forth. This subvariety, or “Chap Chye” (stir-fried mixed vegetables) Mandarin as dubbed by the former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong (Goh 1999), is often found in the colloquial language of those who have a fairly low proficiency of Mandarin. Due to its heavy code-mixing , people may doubt whether this colloquial form should be categorized as Huayu.

Finally, the mesolect is a variety between the acrolect and the basilect, which is widely used by those Singaporeans proficient in the language and in mass media as well. In other words, mesolect Huayu is the daily language for most Chinese speakers in Singapore. Albeit the differences in pronunciation , vocabulary , and grammar from Putonghua, it is generally intelligible to Chinese speakers in other regions. The examples given in the following section are essentially mesolect usages produced by Singaporean students.

Huayu in Practice: Students’ Entrenched Usage

In this section, some Huayu usages in Singapore are presented in order to demonstrate part of the entrenched linguistic features of this new CL variety. The examples given below were taken from the output elicited by the speaking tasks of those students who participated in the aforementioned project that we conducted to develop the CL speaking proficiency descriptors. Therefore, they may represent the localized usages that have been internalized into young Chinese speakers’ linguistic system. Since Putonghua is widely recognized as the dominant variety of Chinese language currently used across the world, the Huayu usages are examined below with reference to it in order to show the extent to which Singapore Huayu is deviant from Putonghua.

Pronunciation

Huayu in Singapore is different from Putonghua in a number of phonetic distinctions (for a comprehensive investigation, see Li 2004). The discussion here focuses on only one aspect: lexical weak stress. Chinese is a tonal language , and tones have a function of distinguishing word meanings (Chao 1968). Apart from four basic tones specified in the lexicon, a prominent feature of Putonghua pronunciation is the wide use of qingsheng or neutral tone, i.e., unstressed syllables that do not bear any of the four tones. In Huayu, however, there is minimal use of qingsheng in pronunciation. One case is that in Putonghua, the second syllable of some words is pronounced in neutral tone, whereas in Huayu, such syllables are pronounced in their original, non-neutral tones. For instance,

In this example, it can be seen that the word in bold—rènao (bustling)—contains a syllable that is usually pronounced in neutral tone in Putonghua. The neutral-tone syllables are usually pronounced in their original tones in other contexts, such as when they stand alone or appear in the initial position of a word. By contrast, de-neutralization takes place in Huayu pronunciation. That is, Singaporean students tend to pronounce the neutral-tone syllables in Putonghua as their original tones.

Moreover, the suffix of a word is, more often than not, pronounced in a neutral tone in Putonghua .Footnote 6 However, it is very common to hear Singaporean Chinese students pronounce such suffixes as non-neutral tones, as shown in the following examples.

In Putonghua , the verbal suffix de and nominal suffix zi are usually pronounced as neutral tones, and the plural suffix men is an unconditionally neutral-tone syllable or is pronounced as neutral tone in any circumstances in oral communication. In Huayu, however, these syllables are often pronounced as non-neutral tones .

In addition, orientation verbs used immediately behind core verbs are often pronounced in neutral tone in Putonghua. This contrasts with Huayu, wherein the original tones of orientation verbs are pronounced. See the following example produced by Singaporean students,

In this case, Singaporean students pronounce the orientation verbs shàng (to go up) and lái (to come) as their original tones, which deviate from the neutral-tone pronunciations in Putonghua.

Vocabulary

With regard to vocabulary, some objects in the physical world are lexicalized differently in Huayu and Putonghua . For instance, Putonghua uses càishìchǎng, gōngjiāochē and chūzūchē to denote vegetable market, bus, and taxi, respectively, while in Huayu, the corresponding lexical forms are bāshā, bāshì, and déshì, respectively, which are the phonetic loans of Malay/English words pasar, bus, and taxi (dialect transliteration), respectively. Such terms have taken root in Singapore Mandarin and have become essential vocabulary of the Chinese community in Singapore. Apart from these words, some other commonly used lexical forms in Huayu also appeared in the oral speech of the students who participated in our project. In the following examples, the lexical items in bold mark some differences of the vocabulary between Huayu and Putonghua.

In the above examples, it can be seen that Putonghua tends to use wǎn (late), shénme shíhou (when), gōngzuò (to work), and lǐbàiwǔ (Friday), whereas Singaporean students, following the habitual usages of Huayu, used chí, jǐshí, zuògōng, and bàiwǔ, respectively.

In these examples, the same vocabularies have very different usages in Putonghua and Huayu. For instance, bāngmáng (to help) (in contrast to the transitive verb bāngzhù in example 8) and shēngqì (to get angry) in Putonghua are intransitive verbs, yet in Huayu they are used as transitive verbs; lǎnduò (laziness) in Putonghua is a noun (in contrast to the adjective form lǎn), while in Huayu it is used as an adjective.

Grammar

In terms of grammar, Huayu also shows some deviances from Putonghua (see Chen 1986; Goh 2010; Lu et al. 2002). For instance, Lu et al. (2002) state that the grammatical features of Huayu are generally identical to those in Putonghua, yet there are some nuanced differences between the two varieties. The following sentences were produced by Singaporean students when performing the speaking tasks.

In Example 11, the relative position of the adverb duo (much/many, more) and the verb modified differs in Huayu and Putonghua. The adverb is put behind the verb in Huayu, and this word order might have resulted from the influence of English (i.e., the English structure give more ….). In Example 12, the verb you (to have) is used as a perfective aspectual marker in Huayu, while this usage of you is unacceptable in Putonghua, wherein the auxiliary guo tends to be used to fulfill this function. In Example 13, the adverb cai (only) in Putonghua is used to refer to an action that has been completed and there is often an emphasis on the temporal lateness of the action. When referring to an action that has yet to be performed, the adverb zai needs to be used instead of cai. In Huayu, by contrast, the adverb cai is used to refer to the occurrence of an action following another action, regardless of the actual completion state of the action. In Example 14, the verb in reduplication form can be followed by yixia (one time) to indicate a tentative action or an attempt, while in Putonghua, the juxtaposition of reduplication form and yixia is ill-formed. In Example 15, bu keyi, namely the negative form of the modal verb keyi (can), can be used in Huanyu to modify the verb indicating a purpose, whereas in Putonghua, only buneng is acceptable in this circumstance (Lü 1999).

We have demonstrated that the pronunciation , vocabulary and grammar of Huayu used in Singapore exhibit some idiosyncratic features vis-à-vis their Putonghua counterparts. Growing up in a Huayu-speaking society, Singaporean students may feel it comfortable to project Huayu usages in the community into their CL learning. Should such Huayu usages be taken as errors? Due to the lack of specific educational policy hitherto regarding CL norms, CL educators and assessors are often found in a dilemma. In the following section, we turn to discuss the difficulties or challenges we encountered in the process of developing CL proficiency descriptors in Singapore due to the tacitness of the policy for CL standards and norms implemented in the educational system.

Challenges for the Development of CL Proficiency Descriptors

The CL proficiency descriptors that we developed in Singapore are different from those specifically for proficiency testing in that they serve as an official guideline for overall CL education with a broader significance; in other words, the knowledge and skill requirements established for different proficiency levels represent the attainment goals for CL teachers as well as CL learners. Therefore, the establishment of proficiency descriptors must take into account the overall language education policy in Singapore, which also regulates the other two MTLs as well as their feasibility for target learners.

In this spirit, one of the issues that we, as developers and evaluators of the CL proficiency descriptors, could not shun away from was determining what standard and whose standard of CL should serve as a benchmark for CL education in Singapore. The issue, however, was particularly precarious given the fact that in the Singapore context, no official CL standards concerning the norms of phonology , vocabulary , and grammar have ever been promulgated. The challenges we encountered were, to a large extent, attributed to the lack of a legitimized CL standard in Singapore.

In fact, the endonormative versus exonormative competition has long been a central concern in Singapore, a place dubbed as “Sociolinguistic Laboratory” (e.g., Xu and Li 2002). Chen (1999), for instance, reviews some early academic works that discussed sociolinguistic differences between the two norms in the 1980s and 1990s. Wee (2003) discussed the dilemmas in choosing a standard in Singapore’s language policy development. It seems that Putonghua , the most prestigious CL variety in Mainland China and the dominant standard among Chinese community, is often taken as the official standard in Singapore’s practice. However, even though Putonghua is often regarded as the de facto standard for Singapore’s CL teaching and learning, it has never been an officially sanctioned standard (Shang and Zhao 2013). A recent study affirms Putonghua’s position “as the standard language holding unwavering prestige and power” and “as a variety associated with status, education and economic advantage” (Chong and Tan 2013, p. S 134). On the other hand, there are also advocacies for official recognition of the type of Huayu usages as we exemplified in Section “Huayu Usage in Spoken Language: Students’ Output” (Lu et al. 2002; Xu and Wang 2004). As such, giving precedence to either Putonghua standard or Huayu idiosyncrasies would cause a lot of resistance. Cognizant of this contested issue, we, as developers, carefully sought to generate CL proficiency descriptors through observing and analyzing Singaporean Chinese students’ actual usages, and organized the knowledge and skill requirements within an integrated framework that took into consideration the educational principles as well as guidelines stipulated in official curricular documents. However, challenges were still inevitable.

To illustrate, in our analysis of the students’ spoken language outputs, which, as indicated earlier, formed the basis for the formulation of the speaking proficiency descriptors , there was an issue of determining whether certain Huayu forms were acceptable in both lower and higher speaking levels. We realized that a judgment was far from easy to be made in the Singapore context where language issues are often heavily politically tinted (Zhao and Liu 2010). This is because there exists a longstanding tension between language standard in practice and actual usages in the society. As shown earlier in Singaporean students’ CL speech samples, there are a number of language forms in Singaporean Huayu that are deviant from their Putonghua counterparts, yet those forms are widely used and quite acceptable for local Huayu speakers. For example, should the neutral tone be taken as a criterion to determine Huayu proficiency? To date, how to deal with such deviance in CL learning, teaching, and assessment is still a matter of debate in Singapore. If the indigenized Huayu practice is followed, those expressions would be quite acceptable. On the other hand, if Putonghua is taken as a standard or benchmark, those Huayu usages, due to their deviation from such a standard, should be considered as errors in CL education, including assessment. The crux of the matter is that there has been no explicit official policy or fiat to institutionalize the implementation of Huayu or Putonghua norms in the education domain. As a result, how to treat Huayu-specific pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar forms constituted a tremendous challenge when we were developing the CL speaking proficiency descriptors.

In Can-Do statements of proficiency descriptors , accuracy, which is concerned with how well language functions are performed or to what extent a message is found acceptable among native speakers (Ramírez 1995), is usually encompassed as a key category to characterize proficiency levels. Taking the ACTFL speaking proficiency descriptors for instance, the guideline delineates that speakers at the Superior level “are able to communicate with accuracy and fluency”, and “demonstrate no pattern of error in the use of basic structures” (ACTFL 2012, p. 5). However, in the CL speaking proficiency descriptors, with particular consideration of their implications for assessing students’ language performance , we were very cautious to use terms such as “error” or “accurate” and avoided, wherever possible, those expressions that tended to value a single standard of language. Our decision-making was careful and strategic because a linguistic standard or norm remains undefined in official discourse. In cases where descriptors seemed to require a standard-oriented expression, we deliberately left any relevant standard unspecified. For instance, one of the descriptors for Level 5 Pronunciation is as follows.

Pronunciation is clear and comprehensible.

Here, we did not specify the standard, either Putonghua or Huayu, for correctness. This is a compromise we decided to make under the sociopolitical constraint to keep proficiency descriptors uncontroversial regarding the issue of standard and ensure wide acceptance of them among CL practitioners and scholars. We admit that if one raises the question of clarifying the standard against which “correctness” is defined and measured, it would be a challenge that is hard to be responded by us. As a matter of fact, standard-related issues were also recognized as a flammable topic by our MOE collaborators (i.e., curriculum officers of the CPDD) when we sought advice from them during our development of the CL speaking proficiency descriptors.

Pedagogical Dilemmas for CL Teaching

The tacit policy of CL standard in Singapore not only baffled us proficiency descriptor developers and assessors, but also seemed to cause tremendous confusion for frontline teachers. In this section, we take a look at the pedagogical consequences associated with the lack of an explicit CL standard in Singapore.

In any language community, there are always language varieties other than the standard one used by different sub-groups of the community, yet formal policies regulating these non-standard varieties are rare in educational systems (Corson 2001). Earlier in this chapter, we have seen that Huayu usages which deviate from the Putonghua standard abound in Singaporean students’ CL speech. Given the idiosyncrasies of Huayu, one may wonder how CL teachers, as the final gatekeeper of CL standard if any, deal with the discrepancies between Huayu and Putonghua in their teaching and assessment of students’ CL abilities. This is an issue that warrants serious explorations. One thing that merits attention is that in CL classrooms, due to ignorance of the difference between Putonghua and Huayu, teachers sometimes become norm-breakers rather than norm-makers of the exonormative standard (Pakir 1994). In other words, the local teachers may also find themselves more comfortable with the localized usages in their spoken language. To illustrate, on the basis of our previous experience with CL teachers through observing their classroom teaching and assessment practices, it is fairly common to see the permeation of Huayu usages, suggesting that unofficial and covert Putonghua norms could be hard for teachers to follow in practice despite Putonghua’s prevalent influence in the Chinese-speaking world.

On the other hand, in our informal communications with CL teachers, it was revealed that some teachers were very concerned with students’ CL use deviant from Putonghua norms, and they felt frustrated by prevailing Huayu idiosyncrasies in students’ spoken language (and written work) and were often at a loss about how to deal with them. Some CL teachers mentioned to us that in their teaching of vocabulary or grammatical structures , Putonghua norms were often imparted to students. It appeared that most teachers tended to emphasize to students that to play safe in examinations, either school-based or in a high-stakes testing context, the usages in Putonghua should be followed even though there had never been an official declaration on Putonghua norms in the educational discourse in Singapore. In the oral tasks designed to elicit speech samples for our project to develop the speaking proficiency descriptors, we did notice that some students stopped intermittently to adjust or repair their Huayu pronunciations or vocabulary so as to accord with Putonghua usages, even though these unnatural pauses for repair purposes jeopardized the fluency of their overall speech. Such an intriguing observation seems to suggest that students, like their teachers, were also struggling between the two norms; and the rule of thumb for examination purposes reiterated by their teachers, i.e., Putonghua usage is a much safer choice, exerted an influence on their critical awareness of the issue of standard and compelled them to reconcile in this regard.

It also appeared that many teachers showed intolerance to Huayu usages in students’ oral or written works and tended to provide corrective feedback according to Putonghua norm. However, they also complained that their corrections were often to no avail. In view of the reality of students’ persistent Huayu usages against Putonghua norm, some teachers pinpointed the unfairness and implausibility of stigmatizing Singaporeans’ own variety. In other words, the teachers felt that it was hard to convince students that the Huayu they were acquiring and using daily with their family members, friends, and community members in Singapore was a substandard variety teemed with errors. Particularly, the teachers failed to justify themselves when students (or parents sometimes) refuted their corrective feedback by arguing that “everybody in Singapore speaks Huayu in this way, so how can you say it is wrong? For your corrected form, we never use it.” Therefore, teachers were eager to be informed of more explicit and effective strategies to deal with Huayu usages in CL education in Singapore. In addition, given the fact that a significant proportion of CL teachers working in Singapore’s public schools are recruited by MOE from mainland China , Taiwan , and Malaysia , they come along with different language ideologies, which makes the issue of “who speak the best Chinese” even more intricate and complex (Zhao and Shang 2013; Zhao and Sun 2013).

Toward a Solution to the Dilemmas

CL standard or norm has long been a perplexing and controversial issue in Singapore, and empirical evidence shows that there are distinct differences between the perceptions of Huayu and Putonghua in Singaporeans (Chong and Tan 2013). This standard-related issue usually does not interrupt the linguistic life of the general public, but conflict arises when the assessment of language proficiency in the education domain is at stake. We have illustrated in this chapter that the lack of an officially endorsed standard in Singapore’s CL education resulted in a dilemma for the development of speaking proficiency descriptors that we undertook, and the discrepancies in Huayu and Putonghua norm have fettered CL education, engendering a tremendous challenge to language educators, assessors as well as us proficiency descriptor developers. It is, therefore, important that interventional measures at the policy level be taken to address the dilemmas in CL learning, teaching, and assessment.

In reference to Kachru’s (1985) three-circle model of world Englishes , Huayu in Singapore is often categorized as a variety in the Outer Circle of Chinese (Goh 2010). Looking at the issues of standard and norm from a broad perspective, we may find that controversies over what standard and whose standard are not unique to CL education in general and CL education in Singapore in particular, but rather prevalent for second language teaching and assessment in most Outer Circle countries where pluricentric languages (Clyne 1992) are used (e.g., Gupta 1994; Mufwene 2001; Newbrook 1997). In such contexts, the exonormative standard , often prescribed as an official norm, tends to be in tension with local usages, and the advocacy of endonormative or exonormative standards has constituted a seemingly everlasting debate in many educational systems (e.g., Bex and Watts 1999; Bruthiaux 2006; Newbrook 1997).

Back to CL language standard in Singapore, it is clear that feasible and applicable language norms should be established for the good of CL education and assessment. The questions are as follows: who should set the norm for Huayu and which standard or norm will be the most suitable and beneficial?

For the norm-setting in Singapore as to whether conducted by educational authorities or policy-makers in government agencies, we contend that educated and proficient Huayu speakers rather than Putonghua speakers should be committed to this function. As Mufwene (1997, 2001) argued, reliance on native language speakers to set norms for second language learners is undesirable, and proficient local speakers should serve as the arbiter of a community norm. With respect to the standard variety, Corson (2001) suggests that we should promote a variety “that is widely used, provides a more effective means of communication across contexts than non-standard varieties. …it meets the acquired interests of and expectations of many groups, rather than just the interests of its more particular speakers” (p. 76). In light of this, the promotion of Putonghua standard in the Singapore Chinese community does not seem feasible in that the exonormative standard stands aloof of the expressive needs of Huayu speakers. An endonormative standard might be more relevant in this regard.

In order to establish a feasible endonormative standard, as Gupta (1986) suggests, three criteria need to be considered: (1) local prestige usage (written, not informal), (2) usage not locally stigmatized, and (3) usage not internationally stigmatized. In our view, the acrolect variety of Huayu can meet the criteria, thus can be a possible candidate to serve as CL standard in Singapore Chinese community. However, before codifying the acrolect and employing it as a major pedagogical vehicle in education, more research is needed to find out the habitual and generally accepted usages found in the local community, and integrate them into the indigenized norm. In addition, perceptions of CL speakers in the Singapore Chinese community toward Putonghua and Huayu should be explored to find out their desirability as CL norms in Singapore. When a consensus has been reached concerning the standardization of the acrolect of Huayu, the government should endorse its function as a standard for CL. After all, an indigenized standard with official authority is the ultimate solution to the dilemmas emerging in CL education. Specifically in the domain of assessment, we argue that language assessment should focus more on students’ communicative ability than accuracy of language forms; language features that do not conform to Putonghua norm should not be penalized in CL assessment as long as they cause no harm to intelligibility or communication of meanings. This argument also seems to align with the CL curriculum in Singapore where willingness to communicate is privileged over language forms.

Concluding Remarks

Language is rooted in social life and nowhere is this more apparent than in the ways in which language proficiency is assessed. As Li (2010) indicates, language assessment is in itself a social phenomenon, and assessing an individual’s language abilities inevitably involves making assumptions of what is expected to be the standard. Standards have long been used to enforce social values throughout educational systems, and tests are the instruments that operationalize and implement standards. In other words, the social and political functions of standard and standardization not only constitute an aspect of identity, but also serve as the point of insertion of power, or in Foucault’s term, they can be experienced as exercises in subjection to power (Foucault 1983). Standard is about “who set the rule of the game” (Smith 1997) and all language tests have implications of value and social consequences (Hubley and Zumbo 2011).

Previous discussions about language assessment tended to be fundamentally asocial and treated language competence as individual cognition that can be simply subject to psychometrics , ignoring the facts that language is rooted in society and language assessments play a role in implementing policies on education in a particular social setting. In a multilingual community, which language variety is more prestigious, and thus more correct (or standard), than others is both sociopolitically and pedagogically complex and sensitive. In Singapore, an increasingly postmodern society, CL classes in schools are attended by learners with diversifying backgrounds (e.g., immigrants from China and other Chinese-speaking polities as well as locally born Singaporean students), which has inevitably come forward as a big concern for both CL assessors and classroom teachers with a language standard or norm remaining undefined in the education domain.

Singapore is the only polity outside of the Greater China where Mandarin is designated by state as an official language , which shows its significant position in the linguistic life and education in the nation (Ang 1999). Putonghua, as an exonormative standard , has been tacitly taken as the benchmark for CL education in Singapore. However, due to concerns that pertain to political sensitivity, neither the Singapore government nor educational authorities in the country have legitimized the adoption of either Putonghua or indigenized Huayu as a standard in CL education and assessment. Without an officially sanctioned standard in place, students’ CL outputs flavored with idiosyncratic Huayu usages are hard to be assessed in due terms, which was a big hurdle for our development of CL proficiency descriptors .

In this paper, with speech examples extracted from students’ performance on oral tasks, we showcased some discrepancies between Huayu and Putonghua usages. On the basis of the comparisons between the two CL varieties, we shared the confusions we had and the compromises we made to accommodate concerns about issues of what standard and whose standard in our development of CL speaking proficiency descriptors. We also discussed how the lack of clearly stated CL standard posed challenges to CL educators and assessors. To establish an appropriate and accessible CL standard, we called for more open acceptance of local habitual usages, and suggested that the acrolect variety of Huayu be taken as the standard for Singaporean CL community. In other words, we argued that the CL standard in Singapore should be derived from the usages of its speakers instead of being forced to be benchmarked on Putonghua. Moreover, we suggested that endeavors should also be made to codify the entrenched acrolect. This is because people are inclined to refer to the codified variety as a reliable source. As Milroy and Milroy (1985) indicate, “[t]he attitudes of linguists (professional scholars of language) have little or no effect on the general public, who continue to look at dictionaries, grammars and handbooks as authorities on ‘correct’ usage” (p. 6). Thus, an endonormative standard accommodating local usages, once established, would be able to resolve the prolonged dilemmas in CL learning, teaching, and assessment in Singapore. Currently, there are no governmental or educational institutions in Singapore that assume responsibility or govern language use in the educational domain. We contend that such official agencies should be established and more tolerant and pluralist approaches be taken toward CL standardization.

Finally, we discussed that the issues associated with exonormative and endonormative standards are not unique to CL education and assessment in Singapore, but rather have wider implications for Chinese diaspora all over the world and are also relevant to other societies where there is a precept-practice gap with respect to the issue of standard in language education and assessment. This research should be helpful for understanding the standard-related problems involved in second language education and assessment and contribute to the satisfactory solution toward resolving the controversies.

Notes

- 1.

For the differences between speaking and spoken interaction and between writing and written interaction, please see Zhu (2014).

- 2.

The full title of the project was “Development of the Proficiency Descriptors Framework of the Teaching, Learning and Assessment of Mother Tongue Languages in Singapore.” The Chinese part was the prototype for the other two MTLs, i.e., Malay and Tamil languages.

- 3.

This selection criterion was set up with a purpose to screen out students with extremely high or extremely low CL proficiencies so that the participants represented the normal and average level of CL speaking for each stage. This selection was mainly done by the CL teachers in the participating schools according to their prolonged observation to the students’ daily performance in CL speaking. In addition, the research team also sifted out obviously unsuitable participants during the tasks.

- 4.

Whether there are significant differences between Singaporean Huayu and other varieties, particularly Taiwan Guoyu, is a complicated issue. Admittedly, many of the so-called Singapore-specific or unique linguistic features that are noted by researchers are also squarely shared by Taiwan Guoyu. The main reason for the high-level similarities between Singaporean Huayu and Taiwan Guoyu might be due to the fact that the bulk of the population in both polities are originally native speakers of Hokkien, a Southern Chinese dialect that exerts considerable influence on Mandarin. Other reasons may include the strong presence of Taiwan Guoyu speakers in local media before the 1980s (Kuo 1985, pp. 115, 131) and the popularity in Singapore of TV drama series and recreational programmes produced in Taiwan. A detailed discussion on how and why Taiwan Guoyu and Singapore Huayu share a lot of similarities would take us too far afield from the focus of this chapter. Interested readers may refer to Guo (2002), Li (2004) and Khoo (2012).

- 5.

In a creole continuum, acrolect is the variety that approximates most closely the standard variety of a major international language, as the English spoken in Guyana or Jamaica; basilect is the variety that is most distinct from the acrolect; and mesolect is any variety that is intermediate between the basilect and the acrolect.

- 6.

This refers mainly to inflection-like suffixes in Chinese. There are derivation-like suffixes in Chinese that are not pronounced in neutral tone, such as 者 zhe and 家 jia.

References

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages [ACTFL]. (2012). ACTFL proficiency guidelines 2012. Alexandra, VA: ACTFL Inc.

Ang, B. C. (1999). The teaching of the Chinese language in Singapore. In S. Gopinathan (Ed.), Language, society and education in Singapore: Issues and trends (pp. 333–352). Singapore: Times Academic Press.

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bex, T., & Watts, R. (1999). Standard English: The widening debate. London: Routledge.

Bokhorst-Heng, W. (1999). Singapore’s Speak Mandarin Campaign: Language ideological debates in the imagining of the nation. In J. Blommaert (Ed.), Language ideological debates (pp. 235–266). New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bruthiaux, P. (2006). Restandardizing localized English: Aspirations and limitations. International Journal of Sociology of Language, 177, 31–49.

Chao, Y. R. (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chen, C. Y. (1986). Xinjiapo Huayu Yufa Tezheng (Syntactic features of Singapore Mandarin). Yuyan Yanjiu (Studies in Language and Linguistics), 1, 138–152.

Chen, P. (1999). Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chew, C. H. (2007). Lun quanqiu yujing xia huayu de guifan wenti (Standardization of the Chinese language: A global language). Yuyan Jiaoxue Yu Yanjiu (Language Teaching and Research), 4, 91–96.

Chong, R. H. H., & Tan, Y. Y. (2013). Attitudes toward accents of Mandarin in Singapore. Chinese Language & Discourse, 4(1), 120–140.

Clyne, M. (1992). Pluricentric languages: Different norms in different nations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Corson, D. (2001). Language diversity and education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of references for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

CPDD (Curriculum Planning and Development Division). (2015). 2015 syllabus Chinese language primary. Singapore: Ministry of Education.

Darling-Hammond, L., & McCloskey, L. (2008). Benchmarking learning systems: Student performance assessment in international context. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Department of Statistics. (2014). Population trends 2014. Singapore: Department of Statistics.

Foucault, M. (1983). The subject and power. In H. Dreyfus & P. Rabinow (Eds.), Michel Foucault: Beyond structuralism and hermeneutics (pp. 208–226). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Fulcher, G., Davidson, F., & Kemp, J. (2011). Effective rating scale development for speaking tests: Performance decision trees. Language Testing, 28(1), 5–29.

Goh, C. T. (1999). Speech by Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong at the 70th Anniversary Celebration Dinner of the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan on Saturday, September 4, 1999 at 7:45 PM at the Neptune Theatre Restaurant. Press Release. Singapore: Singapore Ministry of Information and the Arts.

Goh, Y. S. (2010). Hanyu Guoji Chuanbo: Xinjiapo Shijiao (Global spread of Chinese language: A perspective from Singapore). Beijing: Commercial Press.

Guo, X. (2002). Yu neiwai Hanyu xietiao wenti chuyi (A rudimentary suggestion on integration of Mainland China and overseas Mandarin). Applied Linguistics (Yuyan Wenzi Yingyong), 3, 34–40.

Gupta, A. F. (1986). A standard for written Singapore English. English World-Wide, 7(1), 75–99.

Gupta, A. F. (1994). The step-tongue: Children’s English in Singapore. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Hubley, A. M., & Zumbo, B. D. (2011). Validity and the consequences of test interpretation and use. Social Indicators Research, 103, 219–230.

Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In R. Quirk & H. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11–30). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Khoo, K. U. (2012). Malaixiya yu Xinjiapo Huayu cihui chayi jiqi huanjing yinsu (Malaysia and Singapore Mandarin lexical differences and the environmental factors). Journal of Chinese Sociolinguistics (Zhongguo Shehui Yuyanxue), 12, 96–111.

Kuo, E. C. Y. (1985). Languages and society in Singapore (Xinjiapo de Yuyan yu Shehui). Taipei: Zhengzhong Press.

Li, C. W.-C. (2004). Conflicting notions of language purity: The interplay of archaising, ethnographic, reformist, elitist, and xenophobic purism in the perception of standard Chinese. Language & Communication, 24(2), 97–133.

Li, W. (2010). The nature of linguistic norms and their relevance to multilingual development. In M. Cruz-Ferreira (Ed.), Multilingual norms (pp. 397–404). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Lu, J. M., Zhang, C. H., & Qian, P. (2002). Xinjiapo Huayu Yufa De Tedian (The grammatical features of Singapore Mandarin). In C.-H. Chew (Ed.), Xinjiapo Huayu Cihui Yu Yufa (Vocabulary and grammar in Singapore Mandarin) (pp. 75–147). Singapore: Lingzi Media.

Lü, S. X. (1999). Xiandai Hanyu Babai Ci (Eight hundred words in modern Chinese). Beijing: Commercial Press.

McNamara, T. (2001). Language assessment as social practice: Challenges for research. Language Testing, 18, 333–349.

McNamara, T. (2008). The socio-political and power dimensions of tests. In E. Shohamy & N. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education: Language testing and assessment (pp. 415–427). New York: Springer Science+Business Media L.L.C.

Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1985). Authority in language. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

MTLRC (Mother Tongue Language Review Committee). (2011). Nurturing active learners and proficient users: 2010 Mother Tongue Languages Review Committee report. Singapore: Ministry of Education.

Mufwene, S. (1997). Native speaker, proficient speaker, and norm. In R. Singh (Ed.), Native speaker: Multilingual perspective (pp. 111–123). New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Mufwene, S. (2001). New Englishes and norm-setting: How critical is the native speaker in linguistics. In E. Thumboo (Ed.), The three circles of English (pp. 133–141). Singapore: Unipress.

Newbrook, M. (1997). Malaysian English: Status, norms, some grammatical and lexical features. In E. Schneider (Ed.), Englishes around the world, Vol 2: Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Australia (pp. 229–256). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Newman, J. (1988). Singapore’s speak Mandarin campaign. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 9, 437–448.

North, B., & Schneider, G. (1998). Scaling descriptors for language proficiency scales. Language Testing, 15(2), 217–263.

Pakir, A. (1994). English in Singapore: The codification of competing norms. In S. Gopinathan, A. Pakir, W. K. Ho, & V. Saravanan (Eds.), Language, society and education in Singapore: Issues and trends (pp. 92–118). Singapore: Times Academic Press.

Platt, J. T., & Weber, H. (1980). English in Singapore and Malaysia: Status, features, functions. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Ramírez, A. G. (1995). Creating contexts for second language acquisition: Theory and methods. London: Longman.

Rudner, L. M., & Boston, C. (1994). Performance assessment. ERIC Review, 3(1), 2–12.

Shang, G. W., & Zhao, S. H. (2013). Huayu Guifanhua De Biaozhun Yu Luxiang: Yi Xinjiapo Huayu Weili (The standard and direction of Huayu codification: A case study of Singapore Mandarin). Yuyan Jiaoxue Yu Yanjiu (Language Teaching and Research), 3, 82–90.

Shohamy, E. (2007). Language tests as language policy tools. Assessment in Education, 14(1), 117–130.

Smith, M. J. (1997). Policy networks. In M. Hill (Ed.), Policy process: A reader (pp. 76–86). New York: Routledge.

Wang, C. M., Lee, W. H., Lim, H. L., & Lea, S. H. (2014, 5). Development of the proficiency descriptors framework for the teaching, learning and assessment of mother tongue languages in Singapore. Paper presented in 40th IAEA (International Association for Educational Assessment) Annual Conference. Singapore.

Wang, H. D. (2002). Xinjiapo Huayu Teyou Ciyu Tanwei (An investigation of the Singapore Mandarin vocabulary). In C.-H. Chew (Ed.), Xinjiapo Huayu Cihui Yu Yufa (Vocabulary and grammar in Singapore Mandarin) (pp. 75–147). Singapore: Lingzi Media.

Wee, L. (2003). Linguistic instrumentalism in Singapore. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 24(3), 211–224.

Xu, D., & Li, W. (2002). Managing multilingualism in Singapore. In W. Li, J. D. Marc, & A. Housen (Eds.), Opportunities and challenges of bilingualism (pp. 275–295). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Xu, J., & Wang, H. (2004). Xiandai Huayu Gailun (Introduction to modern Huayu). Singapore: Global publishing.

Zhao, S. H., & Liu, Y. B. (2010). Chinese education in Singapore: The constraints of bilingual policy from perspectives of status and prestige planning. Language Problems and Language Planning, 34(3), 236–258.

Zhao, S. H., & Shang, G. W. (2013, 7). “Who speaking Chinese best”: Reflections and suggestions for the issues emerging from developing exemplars of the education oriented speaking and spoken interaction proficiency descriptors in Singapore. Paper presented at the 10th International Symposium of Teaching Chinese to Foreigners. Hohhot, China: Inner Mongolia Normal University.

Zhao, S. H., & Sun, H. M. (2013, 7). Chinese language teachers from China and Chinese language in Singapore: Towards an integration of the two. Paper presented at the 10th International Symposium of Teaching Chinese to Foreigners. Hohhot, China: Inner Mongolia Normal University.

Zhu, X. H. (2014). Jiangou cujin xuexi de yuwen lingting, shuohua yu kouyu hudong de pingjia Tixi (A system of assessing students’ listening, speaking and oral interaction skills for implementing assessment for learning (AfL) in Chinese language education). Huawen Xuekan (Journal of Chinese Language Education), 6(1), 1–21.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their appreciation for the comments from the anonymous reviewers on an earlier draft of this article. All errors and omissions in this version are, of course, our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shang, G., Zhao, S. (2017). What Standard and Whose Standard: Issues in the Development of Chinese Proficiency Descriptors in Singapore. In: Zhang, D., Lin, CH. (eds) Chinese as a Second Language Assessment. Chinese Language Learning Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4089-4_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4089-4_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-4087-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-4089-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)