Abstract

Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK, 汉语水平考试) is China’s national standardized test designed to assess the Chinese language proficiency of non-native speakers such as foreign students and overseas Chinese. This chapter opens with a brief account of the history and development of HSK over the past thirty years (1984–the present): How it came into being, the aim of the test, the levels of the test, and the outline of the test. For the convenience of discussion, this chapter divides the development of HSK into three stages: Old HSK, HSK (Revised), and New HSK. The review indicates that HSK has developed from a domestic test to an influential international proficient test; it has expanded from a test with a focus on assessment of linguistic knowledge to a test of all four language skills (i.e., listening, reading, writing, and speaking); its exam outline has also undergone huge revisions to better meet the demands of the examinees and the society. Based on the history and development of HSK, the last section discusses its future prospects with challenges identified and suggestions proposed.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Since the inception of the Open-Door Policy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the People’s Republic of China has witnessed the deepening of communication with the outside world in a variety of fields, including education. In the past few decades, there has been a steady increase in the influx of students from foreign countries coming to study in China (Meyer 2014; Wang 2016), and Chinese programs outside of China have also seen fast growth (Zhang 2015; Zhao and Huang 2010). The increasing interest in studying Chinese language and culture has led to a lot of discussions not only in how Chinese language curriculum and pedagogy could best serve the learning needs of learners of Chinese as a second language (CSL) or foreign language (CFL) but also in how learners could be assessed appropriately for diverse academic as well as professional purposes. Within the context of this changing landscape of CSL/CFL education, HSK (acronym of Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi or the pinyin of 汉语水平考试; literally translated as Chinese Proficiency Test) was developed in China and later became the country’s national standardized test of Chinese language proficiency for non-native speakers.

HSK was first developed in 1984 by the HSK Testing Center of Beijing Language Institute (now Beijing Language and Culture University, which is often referred to as Beiyu [北语], the short form of the university’s Chinese name). It is the predecessor of New HSK (新汉语水平考试), which is currently administered and promulgated both within and outside of China by Hanban (汉办, the colloquial abbreviation for 中国国家汉语国际推广领导小组办公室 [Zhongguo Guojia Hanyu Guoji Tuiguang Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi], the Chinese name of the Chinese Language Council), a non-government organization affiliated with the Ministry of Education (MOE) of China. Hanban is also the executive headquarters of the Confucius Institutes (CI) (Li and Tucker 2013; Zhao and Huang 2010) and is committed to making Chinese language teaching resources and services available to the world. Over the past thirty years, HSK has developed from a domestic test for assessing foreign students preparing to study or studying in China to an influential international test of Chinese language proficiency that serves assessment needs and purposes in diverse contexts. It has expanded from testing only listening and reading skills at one level in its earlier form to all language skills across a wide range of language skills and performance and proficiency levels. The testing outlines and guidelines of HSK have also undergone substantial revisions to better meet the demands of examinees and society.

This chapter aims to provide a historical review of HSK and its reforms and discusses its challenges and future directions as an international test of Chinese language proficiency. It opens with a brief account of the history and development of HSK over the past thirty years (1984–the present): How it came into being and its aims, levels, and testing outlines at different historical periods. For the convenience of discussion, this chapter divides the development of HSK into three stages, namely Old HSK (1980s–2000s), HSK Revised (2007–2011), and New HSK (2009 onward) and discusses each stage in one of the three sections that follow. Based on this historical review, the last section of this chapter discusses the future prospects of HSK with challenges identified and suggestions proposed. It is hoped that the review in this chapter with a focus on HSK has broader significance to theory and practice of CSL/CFL assessment and language assessment in general.

Old HSK (1980s–2000s): Emergence and Growth

“Old” is added by the author to refer to the early stage of HSK development and make a differentiation from the versions of reformed HSK at the two latter stages. In other words, Old HSK is by no means the official title of HSK testing in its earliest stage.

The development of HSK was first initiated in 1984 by a team of experts in the field of CSL teaching and assessment in the HSK Testing Center at Beiyu, which, according to the university profile, is “the only university of its kind in China that offers Chinese language and culture courses to foreign students” and “has the longest history, the largest size and the most well qualified academic faculty” in the area of teaching Chinese and promoting Chinese culture to non-native speakers of Chinese.Footnote 1 Given the university’s unique identity, it did not seem a surprise that Beiyu undertook the earliest mission of developing a Chinese proficiency test for foreign students in China. This section addresses the historical development of HSK in its pioneer stage in terms of key events, test format, achievements, and limitations.

The first or earliest form of HSK came into being in 1985 for Chinese proficiency testing at only one level, that is, HSK (Basic), which targeted test-takers with Chinese proficiency at the elementary and intermediate levels. In 1988, the first public HSK test was held at Beiyu, and three years later, it was launched at National University of Singapore as its first attempt at overseas promotion of HSK. In 1992, HSK was officially made a national standardized test of Chinese for non-native speakers of Chinese, with the release of the document entitled Chinese language proficiency test (HSK) guidelines (中国汉语水平考试 [HSK] 办法, Zhongguo Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi [HSK] Banfa) by the then State Education Commission (now the Ministry of Education). After a few years’ development and testing practice, with the consideration of more diverse needs of foreign Chinese learners, the HSK Testing Center started to develop an HSK test for test-takers with an advanced level of Chinese proficiency, that is, HSK (Advanced), which was first introduced in 1993. Later, the original HSK (Basic) was renamed HSK (Elementary and Intermediate). In 1997, the HSK Testing Center also launched the HSK (Beginning) in order to meet the needs of beginning learners on the lower level of Chinese proficiency. By this time, HSK has established itself as a three-level comprehensive test system from the beginning to the advanced level, namely HSK (Beginning), HSK (Elementary–Intermediate), and HSK (Advanced).

These three levels of the HSK test were further divided into eleven grades benchmarked on the teaching of foreign students at Beiyu and Peking University with each level generally subdivided into three grades (Liu et al. 1988). As shown in Table 1.1, within each level, A was the lowest whereas C was the highest in proficiency except that there was an overlap between Basic A and Elementary C, which means these two levels were viewed as similar in proficiency. According to Liu (1999), this arrangement was due to the big transition from the Basic level to the Advanced level. Although there were only three levels in the test, it had four levels of certification: Basic, Elementary, Intermediate, and Advanced. Test-takers were issued a certificate in correspondence to the level tested as long as they met the minimum level of proficiency required within that level of testing (e.g., Basic C, Elementary B, Intermediate C, or Advanced A).

In its initial stage, HSK was primarily a multiple-choice-based written test that paid much attention to assessing test-takers’ language proficiency with a focus on vocabulary and grammar through the format of testing listening and reading (Xie 2011). For example, at the Beginning level (i.e., HSK [Beginning]), only listening comprehension , reading comprehension , and grammatical structure were tested in the form of multiple-choice questions; in HSK (Elementary and Intermediate), an integrated cloze , an assessment consisting of a portion of text with certain words removed where test-takers were asked to restore the missing words based on the context of a reading passage, was added as the fourth section. At the Advanced level (i.e., HSK [Advanced]), in addition to listening comprehension, reading comprehension, and integrated cloze, the fourth section, which carried the name of Comprehensive Expression, asked test-takers to rearrange the order of sentences provided in the test to make a coherently structured paragraph. Another distinctive feature of HSK (Advanced) is that it was the only level of HSK where a writing section and an oral test were included (Jing 2004).

The teaching of Chinese language to international students in China in the late 1980s and early 1990s was largely non-degree bearing and oriented toward proficiency enhancement. The primary aim of Chinese classes then was to ensure international students could become proficient in Chinese so much so that they could attend college science or liberal arts classes for regular native Chinese-speaking students with Chinese as the medium of instruction. At that time, HSK was not a high-stakes test in that a demonstrated level of proficiency through certification was not required, and a certificate of (a certain level of) HSK was not necessarily recognized across universities and colleges in China. This began to change in 1995 when the State Education Commission (now the Ministry of Education) mandated that international students should possess a test certificate that shows their Chinese language proficiency before they could be enrolled in higher institutions across the country. Ever since then, HSK test scores and certificates were acknowledged by more and more educational institutions and business organizations as well, in China, which promoted the popularity and increased the high-stakes status of HSK.

The creation and establishment of the HSK test system were great breakthroughs in the field of teaching Chinese as a second language (TCSL) in China. Before the birth of HSK, there was no systemic, objective, or standardized testing for evaluating international students’ Chinese proficiency. According to Sun (2007), an inherent motivation for developing the HSK was to provide a benchmark by which foreign students’ learning achievement could be assessed for varying decision-making purposes. In other words, to some extent, a consciousness of standards (to guide Chinese teaching in addition to testing) was the impetus or underlying factor for the creation of the HSK testing system. There is no denying that HSK has exerted a great impact on the development of TCSL in China. As Sun (2007) pointed out, there would be no standardization of TCSL without the creation of the HSK.

Throughout the early years of its development from the mid-1980s to late 1990s, HSK has proved itself as a standardized Chinese proficiency test with high reliability and validity , and its item designing, test administration, and grading have all been scientific (Sun 2007). Despite its significance and the great influence on TCSL in China then, HSK, as it was initially designed and structured, also raised a lot of concerns and bore some inevitable limitations. To begin with, the rationale of early HSK testing was a reflection of CSL teaching at that time in China. Liu (1983) held that there was a connection between the ways foreign languages were tested with the ways they were taught. For example, the teaching of Chinese to international students then had a primary focus on the training in linguistic knowledge with little emphasis on the communicative use of the language in real life. Under such an influence, HSK, at its initial stage, placed an emphasis on testing linguistic accuracy rather than language use or language performance (Wang 2014), despite the knowledge now shared by second language acquisition scholars, language testers, as well as teachers that linguistic accuracy does not translate into socially and culturally appropriate use of the target language and thus could not properly measure test-takers’ actual language proficiency (Meyer 2014; Xie 2011). Take HSK (Elementary and Intermediate) as an example; it consisted of four sections of test questions, namely listening comprehension, grammatical structure, reading comprehension, and integrated cloze. Except the integrated cloze questions, which accounted only 10% of the test score, the rest of test questions were all multiple choice (around 90%), and there was no testing at all for language performance, such as writing and speaking, at this level.

No Chinese language proficiency standards were available for international students to guide the development of HSK at its early stage. Thus, interestingly, as noted earlier, HSK developers hoped to use the test and its benchmark levels to guide TCSL practice instead of standards-based language teaching and assessment practice. Consequently, HSK developers chose to refer to the teaching syllabi of a few universities for foreign students and dictionaries for native Chinese-speaking users for the selection of grammatical structures and vocabulary to be considered for constructing test questions. The graded wordlists and grammatical structures in HSK exam outlines or guidelines then had to be revised and adjusted in accordance with how a few universities required their foreign students to learn at different levels. As a result, scholars questioned the criteria of such choices and asserted that the choice of wordlists and grammatical structures could be too prescriptive and narrow in scope (Liu 1999; Wang 2014). Due to these limitations, HSK developers began to undertake significant reforms on the test in the past decade. The forthcoming sections focus on what changes have been made to the Old HSK via two different lines of efforts and why such changes have taken place.

HSK Revised (2007–2011): Beiyu’s Effort to Reform HSK

After nearly twenty years’ practice, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, HSK has become one of the most influential and authoritative Chinese proficiency tests in the world. A large increase in test-takers was witnessed both domestically and internationally. It was estimated that about a million people took the test from 1990 to 2005 (Sun 2009). Along with the increasing popularity of the HSK, complaints about the drawbacks of the test also emerged from both test-takers and CSL practitioners, two major ones being its difficulty level and an orientation toward linguistic knowledge rather than skills for real communication (Meyer 2014).

Based on the feedback from all stakeholders, efforts were made to reform the (Old) HSK test to meet the increasingly diverse needs of examinees both in China and abroad. Two separate efforts were taken by two different agencies to reform the Old HSK. One was from the HSK Testing Center of Beiyu, the original developer of the HSK; the other was from Hanban. These two agencies took two different approaches to revising the HSK to better meet the needs of targeted test-takers in and outside of China in the first decade of the twenty-first century. For a better discussion on the innovation of these two approaches, this section focuses on the effort Beiyu made in revising the Old HSK, which resulted in HSK (Revised), and then, the next section will specifically address Hanban’s reform effort, which led to the New HSK.

As discussed in the previous section, the Old HSK had three levels (i.e., Beginning, Elementary and Intermediate, and Advanced) with 11 grades; its unique structure was not aligned with other established proficiency standards or standardized language tests , which affected its wider promotion and recognition in the world. As Meyer (2014) pointed out, the (Old) HSK score and the level system were not easy to understand, which made it difficult for stakeholders to interpret the meaning of HSK scores, particularly when the scores needed to be compared with those of other international language proficiency tests. Since 2007, the HSK Testing Center at Beiyu has begun to revise the Old HSK. The improved or revised version of the HSK (hereafter, HSK [Revised]) consisted of three levels: HSK (Revised, Elementary), HSK (Revised, Intermediate), and HSK (Revised, Advanced). According to HSK Testing Center (2007), the test structure of the HSK (Revised), compared to the Old HSK, is more reasonable in testing item design and better reflects the principles of language teaching and acquisition (Spolsky 1995).

To begin with, the HSK (Revised) began to pay more attention to testing examinees’ real communicative competence in addition to linguistic knowledge . For example, the HSK (Revised) added into the elementary and intermediate levels (i.e., HSK [Revised, Elementary] and HSK [Revised, Intermediate]) a component that tests speaking, which used to be tested only at the Advanced level (i.e., HSK [Advanced]). With this change, test-takers at all levels now have a choice of testing their speaking in Chinese in correspondence to their actual language proficiency. Such an improvement also indicated a shift from a more vocabulary and grammar oriented paradigm to a more usage or performance based paradigm in the designing of the test (Meyer 2014). In addition to the test format changes, HSK (Revised), compared to its predecessor or the Old HSK, includes more diverse items for testing Chinese speaking and writing . Grammatical structures, based on test-takers’ feedback, were no longer a stand-alone section and tested in a decontextualized way; rather, they are integrated into the test of reading, speaking, and writing. In the HSK (Revised), the integrated cloze section, which required Chinese character writing , was totally removed due to its duplication with a separate writing section.

Another revision in the HSK (Revised) is that multiple-choice test items are reduced, and the test is characterized by more integrated testing of language skills and performance. For example, writing after listening and speaking after listening are added on top of multiple-choice questions to test examinees’ comprehensive language skills. As for testing reading comprehension, HSK (Revised, Intermediate) includes questions that ask test-takers to identify errors from one sentence as well as traditional multiple-choice questions; at the Advanced level (i.e., HSK [Revised, Advanced]), reading comprehension questions consist of error identification from one sentence, reordering of scrambled sentences, and questions that test fast reading skills.

New HSK (2009 Onward): Hanban’s HSK Reform

This section turns to the line of effort that Hanban has taken to reform the (Old) HSK. The outcome of the reform is the New HSK, which was officially launched in 2009 by Hanban. As indicated at the beginning of this chapter, Hanban is the executive body of Chinese Language Council International and also headquarters of the Confucius Institute (CI) . It is a non-profit organization affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education committed to the global promotion of Chinese language and culture.Footnote 2 Ever since the first CI was established in South Korea in 2004, Hanban has established over 480 CIs and many more Confucius Classrooms around the world with overseas partners in the next 10 years.Footnote 3 This global promotion of Chinese language and culture programs has arguably brought about a lot of assessment demands. Among the many missions that CIs have for advancing China’s soft power (Zhang 2015; Zhao and Huang 2010), there is the important one of establishing local facilities for promoting the HSK among learners outsides of China.4 With this mission in mind, Hanban’s efforts to upgrade the HSK took a different approach than Beiyu did. An important initiative of Hanban’s reforming effort was to lower the test-taking threshold to cater to the needs of test-takers with a more diverse range of learning experience and proficiency in Chinese so that more learners around the globe could be attracted to take the test.

An important note to make here before a detailed discussion on the New HSK is the debate among HSK developers on who owns the HSK along with the promotion and reforms of the test: HSK Testing Center at Beiyu, which is the early developer of the HSK, or Hanban, which was established with support from the Chinese government for global promotion of Chinese. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to offer a detailed account of the debate (interested readers may refer to this Chinese news report for detailsFootnote 4), it is clear that the separate reforms by the two agencies (and hence, two different versions of reformed HSK) have hampered the Chinese government’s effort to regulate and standardize its initiative to advance the country’s soft power. In 2010, an agreement on the intellectual property of HSK was made between Hanban and Beiyu, with Hanban becoming the only property owner of HSK. The HSK (Revised) tests conducted by Beiyu came to a complete stop in 2011, and Beiyu agreed to collaborate with Hanban and support Hanban’s development and promotion of the New HSK. In other words, any HSK test after 2011 refers to the New HSK administered by Hanban (Ji 2012); and the New HSK is the second-generation HSK that is promulgated as China’s national Chinese proficiency test for non-native speakers both in and outside of the country. The following subsections first discuss why the Old HSK was reformed into the New HSK and then introduce the structure, format, and major features of the New HSK.

Why New HSK?

The original or Old HSK had met many challenges in its early promotion around the world, a major one being the difficulty of the test to meet the needs of test-takers with a very wide range of Chinese learning experience and proficiency levels and to serve diverse testing purposes. Specifically, the Old HSK was targeted at students who study Chinese in China and coincided with four-year university classroom teaching there. In other words, the Old HSK was largely developed based on four-year Chinese programs for international students at universities in China with little, if any, consideration of those who learn Chinese overseas. Along with the fast increase in the number of overseas Chinese learners in recent years, there is also a very wide range of needs among the learners, which has made potential HSK test-takers more diverse in regards to their learning experience, motivation, and interests in taking the test. For example, people of different ages or educational levels (young learners in K-12 educational settings vs. adult learners in higher institutions), learning Chinese through different ways (informal learning vs. formal learning through classroom instruction), and with different professions may all be interested in taking the HSK for diverse purposes, such as studying in China, career preparation or advancement, or simply taking the test to know the level of their Chinese proficiency.

Under such circumstances, many test-takers outside of China complained that the Old HSK was too hard to reach the level requirement for them to receive a certificate that matches their actual level of proficiency. As Meyer (2014) argued, “many Western learners did not consider Old HSK ‘scores’ a valid measure of their Chinese language competence” (p. 14). For example, after two or more years of formal Chinese learning, lots of learners still had difficulty in passing the Elementary and Intermediate level test (i.e., HSK [Elementary and Intermediate]). As a result, some learners might have felt fearful toward Chinese language and could have easily given up their Chinese learning. In addition to complaints from students themselves on the Old HSK, teachers also thought that the bar of each level of the test was too high to reach for their students. Take the Elementary and Intermediate level in the Old HSK, for example, the vocabulary requirement of the level is up to 3000 words, which could be a big challenge to test-takers. The poor performance on the Old HSK often led to teachers’ resistance to asking their students to take the test. It was argued that the HSK should act as a springboard instead of a stumbling block on the way of learning Chinese (Hanban 2014), or the test should have a positive washback effect on students’ committed interest in learning the language rather than eliminating that interest (Xie 2011). Based on the feedback, like the aforementioned ones, from overseas test-takers and teachers, test developers from Hanban decided that the Old HSK should be reformed.

A major change from the Old HSK to the New HSK is the way in which different languages skills should be tested. According to Meyer (2014), the Old HSK resembled the format of a discrete point test, in which language knowledge was tested through a number of independent elements: grammar, vocabulary, spelling, and pronunciation. These are usually tested by multiple-choice questions and true or false recognition tasks, which are meant to measure test-takers’ language proficiency separately without a comprehensive assessment of their communicative competence . Thus, discrete point tests have been criticized for testing only recognition knowledge and facilitating guessing and cheating, “answering individual items, regardless of their actual function in communication” (Farhady 1979, p. 348). More recently, most scholars favor integrated testing for language performance (e.g., Adair-Hauck et al. 2006), which requires test-takers to coordinate many kinds of knowledge and tap the total communicative abilities in one linguistic event in a format of papers and projects focusing more on comprehension tasks, cloze tasks, and speaking and listening tasks. HSK test reformers have made efforts to change the HSK from a discrete point test to an integrative test.

Another major consideration during the reform of the HSK was the relationship between testing and teaching. In the Old HSK, testing was considered separate from teaching, even though interestingly, the test was originally developed on the basis of the curriculum and instruction for international students in a few universities in China. On the contrary, the New HSK takes the opposite direction: advocating for the principle of integration between teaching and testing in that it aims to “promote training through testing” and “promote learning through testing” (Hanban 2014). It sets clear test objectives to enable test-takers to improve their Chinese language abilities in a systematic and efficient way. While it emphasizes objectivity and accuracy, as is true of any traditional large-scale standardized test , the New HSK, more importantly, focuses on developing and testing examinees’ ability to apply Chinese in practical, real-life situations (Hanban 2010). Overall, there is a clear effort in the development of the New HSK to better serve the learning needs of Chinese language learners through testing.

New HSK: Structure, Levels, and Format of Questions

As a large-scale international standardized test, the New HSK combines the advantages of the original HSK while taking into consideration the recent trends in Chinese language teaching and international language testing. The levels of the New HSK correspond to those of the Chinese Language Proficiency Scales for Speakers of Other Languages (CLPS 4) developed by Hanban,Footnote 5 and there was also an effort to align the levels with those of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe 2002).

The New HSK consists of two independent parts: a written test (by default, the New HSK refers to the written test) and an oral test (HSKK ; acronym of Hanyu Shuiping Kouyu Kaoshi 汉语水平口语考试 or HSK Speaking Test). There are six levels to the written test and three levels to the speaking test. For the written test, it consists of six bands (levels), namely HSK (Level I), HSK (Level II), HSK (Level III), HSK (Level IV), HSK (Level V), and HSK (Level VI). It is apparent that compared with its predecessor, the New HSK has more refined test levels; in particular, the HSKK also has three levels (i.e., Beginning, Intermediate, and Advanced in correspondence to CEFR Levels A, B, and C), thus making more level choices available to learners who want to have their oral proficiency in Chinese tested. Table 1.2 shows the correspondence between the levels of the New HSK (including HSKK), the levels of the CLPS, and the CEFR.

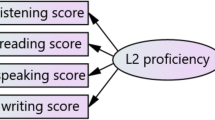

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to provide details about the format of all test sections/questions at each level of the New HSK. Interested readers can refer to the Web site of Hanban.Footnote 6 For a quick overview here, the New HSK (with HSKK included) attaches great importance to all four language skills and reflects a balanced proportion between receptive skills and productive skills , even though it tests primarily listening and reading comprehension at the lower levels (Levels 1 and 2). Pictures are widely used in the lower levels to provide some clues for students’ listening or reading comprehension. Across the six levels, the listening section consists of different types of questions that test listening abilities from as simple as making a true or false judgment on whether a given picture matches a word heard to such complex skills as long conversation and short passage comprehension. The reading section also consists of different types of questions that test different levels and types of Chinese reading; from as simple as matching a printed word (with pinyin at Levels 1 and 2) with a picture to as complex as cloze, sentence reordering, and passage comprehension. Writing is only tested from Level 3, which consists of two parts that ask test-takers to write a complete sentence either rearranging character orders or filling in the missing character in a sentence with pictures given. More complex writing skills, such as keywords and picture-based sentence or essay writing, are tested at Levels 4 and 5. The writing at Level 6 tests the ability to condense a passage from 1000 words to 400 words without personal views added.

HSKK, as the HSK speaking test, is comprised of three levels, all of which have the first part that asks test-takers to repeat or retell what is presented to them—repeating sentences heard at the Beginning and Intermediate levels and retelling a passage presented in print at the Advanced level. The Beginning level also involves answering a number of questions either briefly after the recording of the questions is played or with a minimum of five sentences for each question presented in pinyin . The Intermediate level, in addition to sentence repetition, involves describing two pictures and answering two questions presented in pinyin. At the Advanced level, test-takers, in addition to retelling three passages, are asked to read aloud a passage and answer two questions. All passages and questions are presented in print to the test-takers at the Advanced level.

New HSK: Concluding Remarks

Since it was first launched in 2009, the popularity of the New HSK is fast growing and it has become widely promoted and accepted both in and outside of China. According to Hanban (2014), by the end of 2013, 56 HSK test centers had been established in 31 cities in mainland China, and internationally, there were over 800 overseas test centers in 108 countries and regions and over 370,000 international test-takers took the New HSK in 2013 (Hanban 2014). According to Zhang (2015), by the end of 2014, there had been 475 Confucius Institutes with more than 1.1 million registered students learning Chinese in 126 countries and regions around the globe. It is reasonably anticipated that the increasing number of students in CI should also promote the popularity of the New HSK in the years to come.

The New HSK, on the one hand, retains the former HSK’s orientation as a general Chinese language proficiency test; on the other hand, it has expanded the scope of its predecessor, in particular, the application of its scores for diverse decision making in a globalized world (Wang 2014). The result of the test could not only be used for assessing students’ proficiency and evaluating their learning progress but also be extended to use as a reference: (1) of an educational institution or program for student admission or placement and differentiation in teaching; (2) for employers’ decision making concerning staff recruitment, training, and promotion; and (3) for Chinese program evaluation purposes (e.g., how effective a program is in training Chinese learners) (Hanban 2014).

Despite its increasing popularity and expanded use of test scores, the New HSK is not free of critiques and concerns (Wang 2014). As an example, as indicated earlier (see Table 1.2), there was an effort during the reform of the New HSK to align it with the levels of the CEFR and the CLPS. However, the CEFR does not give specific considerations to Chinese characters, and CLPS also does not seem to pay adequate attention to character competence or competence of Chinese orthography, which is very different from alphabetic languages but an essential part of Chinese language competence. In the New HSK, there is no written test (character writing) at Levels 1 and 2, which does not seem to be aligned with the typical Chinese learning experience of test-takers. Such an arrangement might have resulted from a consideration of the challenge of character writing , particularly among beginning learners/test-takers with an alphabetic language background, despite the fact that these learners/test-takers do typically learn how to write characters as an integral component of their Chinese learning process. A related concern rests on test reformers’ effort to accommodate the testing needs of beginning learners by lowering its difficulty level so that the New HSK could be of interest to test-takers with minimal learning experience and a very limited foundation in Chinese words and grammar. For example, New HSK (Level 1) could be taken by those who have learned 150 words and New HSK (Level 2) by those with 300 words, according to the test outline of the New HSK (Hanban 2010). While these low requirements could make the New HSK more widely appealing internationally, it seems questionable if the effort behind this reform to attract more test-takers, along with Hanban’s global mission to promote Chinese language and culture, would be desirable. In other words, while the number of HSK test-takers might increase as a result of this change, in the long run, this practice could have some negative effects on the promotion of Chinese language internationally (Wang 2014). That is, the easy access to an HSK certificate at such a low standard might weaken the authority of the test itself.

Looking Ahead at the HSK: Challenges and Future Directions

As the historical overview above shows, HSK has undergone major changes and made great advancements in the past thirty years in line with new trends in international language testing and the changing landscape of Chinese teaching and learning around the world. However, HSK has also encountered many challenges despite the recent reforms. In what follows, some challenges the HSK has encountered are discussed, and at the same time, some suggestions are made on the future directions of its development.

First, the test needs to be consistent across levels in light of difficulty and learner diversity in how Chinese is taught and learned in the global context. Meyer (2014) argued that consistency or the lack thereof was a big issue in HSK in that the transition from one level to another is not necessarily similar in the level of difficulty. Take the New HSK vocabulary requirements, for example, for Levels 1, 2, and 3, the required vocabulary is 150, 300, and 600 words, respectively; whereas for Levels 4, 5 and 6, the required vocabulary is 1200, 2500 and 5000 words, respectively. Such a big jump from low to high levels suggests that the beginning level (i.e., Level 1) might be too easy (150 words) (as I also indicated earlier), while the Advanced levels (Levels 5 and 6) may be too hard for test-takers. There are also concerns about some drawbacks in the choices of overall vocabulary (e.g., away from the teaching context of learners outside of China) and the distributions of vocabulary across different levels (Zhang et al. 2010).

Second, as I discussed, the New HSK advocates a close relationship between testing and teaching, arguing that New HSK testing could offer valuable guidelines for teaching practice (Hanban 2014). In reality, such an idea seems more of an expectation or a point to help promote the New HSK than possibly effective in practice in an international context, given, as we all know, that the teaching of Chinese around the world is so diverse in regards to curriculum, teaching force, learners’ needs, and textbooks. Take the textbook in the market, for example, it was estimated that there are over 3300 different kinds of Chinese textbooks on the international market (Pan 2014). There are huge variations in these textbooks in terms of target learners/programs, the principle of material selection, and unit organization, and so on. Many of them were not necessarily published in China with support from Hanban and in alignment with CLPS guidelines, which serve as the basis on which the New HSK was developed. While Hanban has strived to make a lot of curricular materials produced in China available to overseas learners through Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms, it is not uncommon that these materials are not used at all in K-12 as well as university-based Chinese programs. In the USA, for example, K-12 Chinese programs usually do not mandate the use of a textbook series, and university Chinese programs tend to adopt locally produced textbooks, such as Integrated Chinese (Yao and Liu 2009) and Chinese Link (Wu et al. 2010), which are developed on the basis of the National Foreign Language Standards (ACTFL 1995). Consequently, the various levels of the New HSK and the test as a whole could not easily match the curriculum and the development trajectory of overseas students, which effectively makes it challenging for HSK testing results to be used by teachers to guide their teaching and learners to guide their learning practice.

Third, test items need to be updated, and modern technology should be integrated into the test. Scholars have pointed out that there is an urgent need to update the item bank of the HSK, and test items should reflect the development of society in a globalized world, and the gap between HSK test items and social demands should be bridged (Ren 2004). Moreover, despite the current trend of Internet-based, computerized adaptive testing (Suvorov and Hegelheimer 2013), such as TOEFL iBT and Business Chinese Test (BCT; another test administered by Hanban), New HSK is still a largely paper-based, non-adaptive test. Over the past few years, Internet-based New HSK testing has been conducted in some places of the world. However, the test is largely a Web-based version of the paper test with the possibility for test-takers to input Chinese characters through a computer-based input program, as opposed to handwriting, for writing, in addition to enhanced efficiency in test administration and test-taking. Web-based, self-adaptive testing is certainly the direction for HSK’s future development (Sun 2007). Another technology-related issue is computer-assisted scoring of written Chinese. Over the past years of HSK development, there has been some effort to study automated scoring of HSK essays and L2 Chinese essays in general (see Zhang et al. 2016, for a review), such as exploring distinguishing features (e.g., token and type frequency of characters) that predict essay scores (e.g., Huang et al. 2014). However, HSK essay scoring has by far relied on human raters , and at the time of writing this chapter, automated essay scoring (AES) is yet to be applied in HSK testing.

Fourth, there is a need to enlarge the scope of spoken Chinese tested in the HSKK. As I indicated earlier, the current format of the HSKK focuses largely on testing presentational skills, such as repeating sentences or answering questions heard, picture-prompted narration, and reading aloud or retelling. Test-takers’ oral productions are recorded for later scoring. However, there is no testing of test-takers’ interactive use of Chinese, such as with a certified tester as in the case of ACTFL’s Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI) (Liskin-Gasparro 2003; see also Liu, this volume) or between test-takers themselves. The lack of direct testing of spoken interaction seems to constrain the space of the HSKK to meet the needs of test-takers and any washback effect that the test could have on communication-oriented Chinese language teaching and learning.

Finally, what standards to follow is also a big issue that the New HSK needs to deal with while being promoted in an international context. Two types of standards seem particularly relevant. The first concerns the standards for Chinese (or foreign language in general) learning or proficiency development, which was indicated in the first point made above. To recap, a lack of alignment between the standards/proficiency guidelines on which the New HSK is based and those diverse ones on which Chinese curricula are set up around the world would limit the washback effect that HSK developers claim to have on Chinese teaching and learning. The second issue concerns the standard of language. As discussed earlier, Chinese language learners and test-takers are becoming more diverse than ever before. They include not only those non-native speakers who learn Chinese as a Foreign Language , but also descendants of Chinese immigrants in diaspora communities who learn Chinese as a heritage language . These diverse learners tend to speak different varieties of Chinese and have different demands and expectations for Chinese learning and use in their life. What standard or standards of language should a globally promoted test like the New HSK follow? Is Putonghua , the standard variety of Chinese in China and on which the New HSK is based, the sole legitimate standard for international testing of Chinese, or should the New HSK as an international test consider diverse varieties of the language in the Chinese-speaking world? In view of the global spread of Chinese, some scholars recently proposed Global Huayu (literally, language of the Chinese) to capture the evolving nature of Chinese as a lingua franca and discussed its implications for Chinese language teaching and testing (Lu 2015; Seng and Lai 2010; Wang 2009; See also Shang and Zhao, this volume). According to Lu (2015), a preeminent scholar of Chinese linguistics and Chinese as a second language who previously served as the president of the International Society for Chinese Language Teaching (世界汉语教学学会), Global Huayu Putonghua could not and should not be adhered to as the norm in Chinese language teaching, whether it is pronunciation, vocabulary, or grammar. In this regard, the discussion on World Englishes in language testing (Elder and Davies 2006) should be pertinent to HSK and international testing of Chinese in general. However, the HSK testing community has been barely responsive to such an issue.

Conclusion

This chapter provided a historical review on the HSK. Over the past 30 years, HSK has witnessed fast development and established itself as a well-known international test of Chinese proficiency, along with the growth of the discipline of TCFL in China and Chinese government’s global promotion of Chinese language and culture (Sun 2007). Through ongoing reforms, HSK has been updated to meet the diverse needs of test-takers internationally. Despite the progresses highlighted in this historical account, there are also a lot of issues and challenges that have emerged and are yet to be addressed with Hanban’s effort to promulgate the New HSK in an international context. As Meyer (2014) noted, Chinese proficiency testing, be it Old HSK or New HSK, “is strongly affected by the field of language testing, which is mostly dominated by Anglo-Saxon countries, particularly the United States and England” (p. 15). While the effort to align with proficiency guidelines or frameworks like the CEFR is arguably helpful to internationalize the New HSK, there are also issues to be resolved in the development of the test with “Chinese” characteristics. It is hoped that the challenges discussed earlier on Chinese program, curricula, teaching, and learner diversities, among others, will shed light on the future development of the HSK and research on the test and large-scale testing of Chinese proficiency in general.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

Chinese Language Proficiency Scales for Speakers of Other Languages (CLPS) is a guideline document developed by Hanban for teaching Chinese to speakers of other languages. It provided detailed descriptions for five proficiency benchmarks in six areas, including communicative ability in spoken Chinese, communicative ability in written Chinese, listening comprehension, oral presentation, reading comprehension, and written expression. The document serves as an important reference for developing Chinese language syllabi, compiling Chinese textbooks, and assessing the language proficiency of learners of Chinese (Source: http://chinese.fltrp.com/book/410).

- 6.

Source: http://english.hanban.org.

References

Adair-Hauck, B., Glisan, E. W., Koda, K., Swender, E. B., & Sandrock, P. (2006). The integrated performance assessment (IPA): Connecting assessment to instruction and learning. Foreign Language Annals, 39(3), 359–382.

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL). (1995). ACTFL program standards for the preparation of foreign language teachers. Yonkers, NY: Author.

Council of Europe. (2002). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elder, C., & Davies, A. (2006). Assessing English as a lingua franca. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, 282–304.

Farhady, H. (1979). The disjunctive fallacy between discrete-point and integrative tests. TESOL Quarterly, 13, 347–357.

Hanban. (2010). New Chinese proficiency test outline (level 1-6). Beijing: The Commercial Press.

Hanban. (2014). www.hanban.org. Retrieved from http://english.hanban.org/node_8002.htm

HSK Testing Center. (2007). Scheme for a revised version of the Chinese proficiency test (HSK). Chinese Teaching in the World, 2, 126–135.

Huang, Z., Xie, J., & Xun, E. (2014). Study of feature selection in HSK automated essay scoring. Computer Engineering and Applications, 6, 118–122+126.

Ji, Y. (2012). Comments on new Chinese proficiency test. Journal of North China University of Technology, 24(2), 52–57.

Jing, C. (2004). Rethinking Chinese proficiency test HSK. Journal of Chinese College in Jinan University, 1, 22–32.

Li, S., & Tucker, G. R. (2013). A survey of the US Confucius Institutes: Opportunities and challenges in promoting Chinese language and culture education. Journal of Chinese Language Teachers’ Association, 48(1), 29–53.

Liskin-Gasparro, J. E. (2003). The ACTFL proficiency guidelines and the oral proficiency interview: A brief history and analysis of their survival. Foreign Language Annals, 36(4), 483–490.

Liu, L. (1999). The grading system of Chinese proficiency test HSK. Chinese Teaching in the World, 3, 17–23.

Liu, X. (1983). A discussion on the Chinese proficiency test. Language Teaching and Researching, 4, 57–67.

Liu, Y., Guo, S., & Wang, Z. (1988). On the nature and characteristic of HSK. Chinese Teaching in the World, 2, 110–120.

Lu, J. (2015). The concept of Dahuayu meets the demands of Chinese integration into the World. Global Chinese, 1, 245–254.

Meyer, F. K. (2014). Language proficiency testing for Chinese as a foreign language: An argument-based approach for validating the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK). Bern: Peter Lang.

Pan, X. (2014). Nationality and country-specific of international Chinese textbooks. International Chinese Language Education, 2, 154–159.

Ren, C. (2004). Exploratory research on objective scoring of HSK composition. Chinese Language Learning, 6, 58–67.

Seng, G. Y., & Lai, L. S. (2010). Global Mandarin. In V. Vaish (Ed.), Globalization of language and culture in Asia: The impact of globalization processes on language. London: Continuum.

Spolsky, B. (1995). Measured words: The development of objective language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sun, D. (2007). On the scientific nature of HSK. Chinese Teaching in the World, 4, 129–138.

Sun, D. (2009). A brief discussion on the development of the Chinese proficient test. China Examinations, 6, 18–22.

Suvorov, R., & Hegelheimer, V. (2013). Computer-assisted language testing. In A. J. Kunnan (Ed.), Companion to language assessment (pp. 593–613). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Wang, H. (2009). On the cornerstone of Huayu test. Journal of College of Chinese Language and Culture of Jinan University, 1, 83–88.

Wang, R. (2014). Review of the study on the assessment of Chinese as a second language proficiency. Language Science, 13(1), 42–48.

Wang, Z. (2016). A survey on acculturation of international students in universities of Beijing. China Higher Education Research, 1, 91–96.

Wu, S., Yu, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tian, W. (2010). Chinese link. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Xie, X. (2011). Why Hanban developed the new Chinese proficiency test (HSK)? China Examinations, 3, 10–13.

Yao, T., & Liu, Y. (2009). Integrated Chinese. Boston, MA: Cheng & Tsui Company.

Zhang, D., Li, L., & Zhao, S. (2016). Testing writing in Chinese as a second language: An overview of research. In V. Aryadoust & J. Fox (Eds.), Current trends in language testing in the Pacific Rim and the Middle East: Policies, analysis, and diagnosis. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Zhang, J. (2015). Overseas development and prospect of Confucius Institute. Journal of Hebei University of Economics and Business, 4, 122–125.

Zhang, J., Xie, N., Wang, S., Li, Y., & Zhang, T. (2010). The new Chinese proficiency test (HSK) report. China Examination, 9, 38–43.

Zhao, H., & Huang, J. (2010). China’s policy of Chinese as a foreign language and the use of overseas Confucius Institutes. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 9(2), 127–142.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my gratitude to Dr. Dongbo Zhang for his trust and encouragement in including this chapter in the book and his writing and resource support in the writing process. Special thanks also go to the reviewers’ feedback and comments on the early draft of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Teng, Y. (2017). Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK): Past, Present, and Future. In: Zhang, D., Lin, CH. (eds) Chinese as a Second Language Assessment. Chinese Language Learning Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4089-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4089-4_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-4087-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-4089-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)